The Indirect Effect of an Internet-Based Intervention on Third-Party Disability for Significant Others of Individuals with Tinnitus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Participants

- Adults aged 18 years and over who experience tinnitus for a minimum period of 3 months. There was no maximum tinnitus duration.

- A tinnitus severity score of 25 or greater on the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) that indicates the need for an intervention.

- Any configuration of hearing levels (normal or any degree of hearing loss) and any use of hearing devices (using or not using hearing aids). Participants with hearing loss were contacted to ensure they were undertaking additional interventions for their hearing loss.

- Participants were to have access to a computer and the internet and not be undergoing any concurrent tinnitus therapies.

- Any type of tinnitus was considered. Participants with tinnitus that could be associated with other medical conditions, e.g., pulsatile or unilateral tinnitus, were contacted to ensure they were having investigations for this by medical professionals.

- Indications of significant depression (≥15 scores) on the Patient Health Questionnaire PHQ-9

- Indications of self-harm thoughts or intent (i.e., answering affirming on Question 10 of the PHQ-9 questionnaire)

- Reporting any major medical, psychiatric, or mental disorder that may hamper commitment to the program or tinnitus as a consequence of a medical disorder still under investigation

- A clear protocol was set up for these patients. For any participant indicating possible self-harm thoughts or significant depression on the PHQ-9, a psychologist would phone them within 24 h for appropriate management.

- SOs could be a spouse, partner, parent, adult child, sibling, other family members, housemate, or close friend who had a close emotional connection with the individual with tinnitus.

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Outcome Measures for Individuals with Tinnitus

2.6. Outcome Measures for Significant Others

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

3.2. Comparison of Significant Other Completing and Not Completing the Post-Intervention Questionnaire

3.3. Comparison of Significant Other with and without Tinnitus

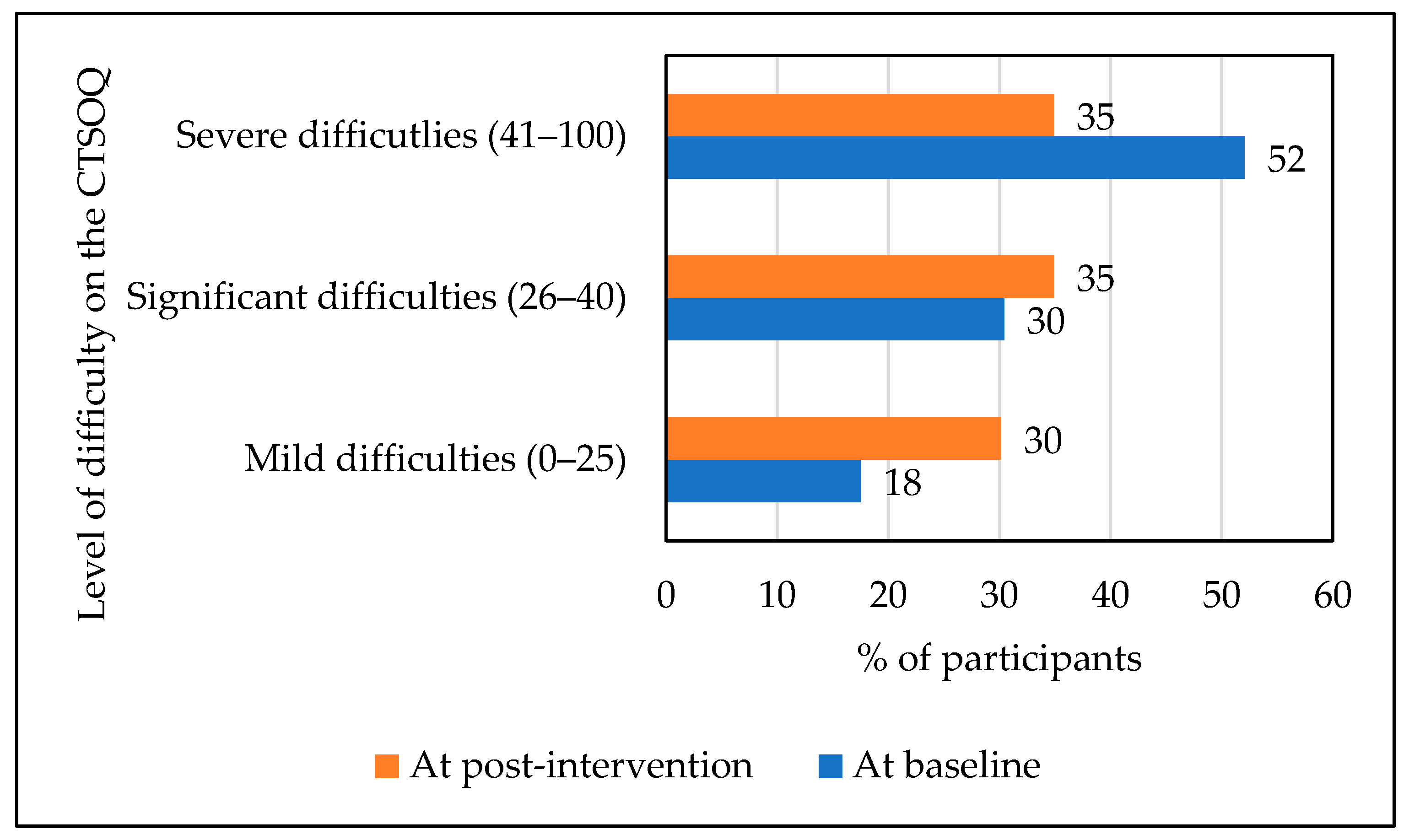

3.4. Impact of Tinnitus on the Significant Others

3.5. Predictions of SO Outcomes at Post-Intervention

3.6. Impact of Tinnitus on Individuals with Tinnitus

3.7. Associations between the Significant Others Third-Party Disability and Post-Intervention Outcomes for Individuals with Tinnitus

4. Discussion

4.1. Indirect Effect of ICBT for Tinnitus on Significant Others

4.2. Predictors of Outcomes Regarding Significant Others Characteristics

4.3. Association between Significant Others and Individuals with Tinnitus Post-Intervention Outcomes

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Federoff, H.J.; Gostin, L.O. Evolving from reductionism to holism: Is there a future for systems medicine? JAMA 2009, 302, 994–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiandaca, M.S.; Mapstone, M.; Connors, E.; Jacobson, M.; Monuki, E.S.; Malik, S.; Macciardi, F.; Federoff, H.J. Systems healthcare: A holistic paradigm for tomorrow. BMC Syst. Biol. 2017, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannotta, R.; Malik, S.; Chan, A.Y.; Urgun, K.; Hsu, F.; Vadera, S. Integrative Medicine as a Vital Component of Patient Care. Cureus 2018, 10, e3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilaran, J.; de Terte, I.; Kaniasty, K.; Stephens, C. Psychological outcomes in disaster responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of social support. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2018, 9, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Chen, Y.X.; He, D.; Zhang, X.; Fan, X. The Relationship Between Caregiver Reactions and Psychological Distress in Family Caregivers of Patients with Heart Failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 35, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mann, F.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Ma, R.; Johnson, S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Lugo, A.; Akeroyd, M.A.; Schlee, W.; Gallus, S.; Hall, D.A. Tinnitus prevalence in Europe: A multi-country cross-sectional population study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 12, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batts, S.; Stankovic, K.M. Tinnitus prevalence, associated characteristics, and related healthcare use in the United States: A population-level analysis. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2024, 29, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E.W.; Manchaiah, V.; Allen, P.M.; Andersson, G.; Baguley, D.M. Exploring tinnitus heterogeneity. Prog. Brain Res. 2020, 260, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, L.; Boecking, B.; Brueggemann, P.; Pedersen, N.L.; Canlon, B.; Cederroth, C.R.; Mazurek, B. Subjective hearing ability, physical and mental comorbidities in individuals with bothersome tinnitus in a Swedish population sample. Prog. Brain Res. 2021, 260, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevis, K.J.; McLachlan, N.M.; Wilson, S.J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological functioning in chronic tinnitus. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 60, 62–86. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, J.W.; Meisel, K.; Smith, E.R.; Quiggle, A.; McCoy, D.B.; Amans, M.R. Depression in patients with tinnitus: A systematic review. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2019, 161, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E.W.; Manchaiah, V.; Andersson, G.; Allen, P.M.; Terlizzi, P.M.; Baguley, D.M. Situationally influenced tinnitus coping strategies: A mixed methods approach. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 2884–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchaiah, V.; Taylor, B. The Role of Communication Partners in the Audiological Rehabilitation; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Barker, A.B.; Leighton, P.; Ferguson, M.A. Coping together with hearing loss: A qualitative meta-synthesis of the psychosocial experiences of people with hearing loss and their communication partners. Int. J. Audiol. 2017, 56, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.; Plexico, L. Couples’ experiences of living with hearing impairment. Asia Pac. J. Speech Lang. Hear. 2012, 15, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grawburg, M.; Howe, T.; Worrall, L.; Scarinci, N. Describing the impact of aphasia on close family members using the ICF framework. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchaiah, V.K.C.; Stephens, D.; Lunner, T. Communication partners’ journey through their partner’s hearing impairment. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2013, 11, 707910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandurkar, A.; Shende, S. Third Party Disability in Spouses of Elderly Persons with Different Degrees of Hearing Loss. Ageing Int 2020, 45, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyykkő, I.; Manchaiah, V.; Levo, H.; Kentala, E.; Rasku, J. Attitudes of significant others of people with ménière’s disease vary from coping to victimization. Int. J. Audiol. 2015, 54, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarinci, N.; Worrall, L.; Hickson, L. The ICF and third-party disability: Its application to spouses of older people with hearing impairment. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 2088–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarinci, N.; Worrall, L.; Hickson, L. The effect of hearing impairment in older people on the spouse: Development and psychometric testing of the Significant Other Scale for Hearing Disability (SOS-HEAR). Int. J. Audiol. 2009, 48, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukes, E.W.; Ulep, A.J.; Andersson, G.; Manchaiah, V. The effects of tinnitus on significant others. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukes, E.W.; Maidment, D.M.; Andersson, G.; Fagelson, M.; Heffernan, E.; Manchaiah, V. Development and psychometric validation of a questionnaire assessing the impact of tinnitus on significant others. J. Comm. Dis. 2022, 95, 106159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukes, E.W.; Andersson, G.; Manchaiah, V. Third party disability for significant others of individuals with tinnitus: A cross-sectional survey design. Audiol. Res. 2023, 13, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, T.; Cima, R.; Langguth, B.; Mazurek, B.; Vlaeyen, J.W.; Hoare, D.J. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD012614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, E.C.; Sandoval, X.C.R.; Simeone, C.N.; Tidball, G.; Lea, J.; Westerberg, B.D. Systematic review and network meta-analysis of cognitive and/or behavioral therapies (CBT) for tinnitus. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G.; Strömgren, T.; Ström, L.; Lyttkens, L. Randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for distress associated with tinnitus. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E.W.; Manchaiah, V.; Allen, P.M.; Baguley, D.M.; Andersson, G. Internet-Based Interventions for Adults with Hearing Loss, Tinnitus, and Vestibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trends Hear. 2019, 23, 2331216519851749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G. Internet-delivered psychological treatments for tinnitus: A brief historical review. Am. J. Audiol. 2022, 31, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E.W.; Andersson, G.; Fagelson, M.; Manchaiah, V. Audiologist-supported internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus in the United States: A pilot trial. Am. J. Audiol. 2021, 30, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E.W.; Andersson, G.; Fagelson, M.; Manchaiah, V. Internet-based audiologist-guided cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus: A randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e27584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E.; Andersson, G.; Fagelson, M.; Manchaiah, V. Dismantling internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus. The contribution of applied relaxation: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2021, 25, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, G.; Kaldo, V. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 60, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E.W.; Vlaescu, G.; Manchaiah, V.; Baguley, D.M.; Allen, P.M.; Kaldo, V.; Andersson, G. Development and technical functionality of an Internet-based intervention for tinnitus in the UK. Internet Interv. 2016, 6, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukes, E.W.; Fagelson, M.; Aronson, E.P.; Munoz, M.F.; Andersson, G.; Manchaiah, V. Readability Following Cultural and Linguistic Adaptations of an Internet-Based Intervention for Tinnitus for Use in the United States. Am. J. Audiol. 2020, 29, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchaiah, V.; Vlaescu, G.; Varadaraj, S.; Aronson, E.P.; Fagelson, M.A.; Munoz, M.F.; Andersson, G.; Beukes, E.W. Features, Functionality, and Acceptability of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Tinnitus in the United States. Am. J. Audiol. 2020, 29, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukes, E.; Andersson, G.; Manchaiah, V.; Kaldo, V. Cognitive Behavioral. Therapy for Tinnitus; Plural Publishing Inc.: Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beukes, E.W.; Manchaiah, V.; Andersson, G.; Maidment, D.W. Application of the behavior change wheel within the context of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus management. Am. J. Audiol. 2022, 31, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, M.B.; Henry, J.A.; Griest, S.E.; Stewart, B.J.; Abrams, H.B.; McArdle, R.; Myers, P.J.; Newman, C.W.; Sandridge, S.; Turk, D.C.; et al. The tinnitus functional index: Development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2012, 33, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA 1999, 282, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, P.H.; Henry, J.L. Tinnitus Cognitions Questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties of a measure of dysfunctional cognitions associated with tinnitus. Int. Tinnitus J. 1998, 4, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henry, J.A.; Griest, S.; Zaugg, T.L.; Thielman, E.; Kaelin, C.; Galvez, G.; Carlson, K.F. Tinnitus and hearing survey: A screening tool to differentiate bothersome tinnitus from hearing difficulties. Am. J. Audiol. 2015, 24, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, K.; Nilsson, A.; Andersson, G.; Hellner, C.; Carlbring, P. Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for significant others of treatment-refusing problem gamblers: A randomized wait-list controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 87, 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Magnusson, K.; Carlbring, P.; Andersson, G.; Gumpert, C.H. The development of an internet-based treatment for problem gamblers and concerned significant others: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Gambl. Stud. 2018, 34, 539–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariss, T.; Fairbairn, C.E. The effect of significant other involvement in treatment for substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 88, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, R.; Stephens, D.; Budd, R. The contribution of spouse responses and marital satisfaction to the experience of chronic tinnitus. Audiol. Med. 2004, 2, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.; Katon, W.; Russo, J.; Dobie, R.; Sakai, C. Coping and marital support as correlates of tinnitus disability. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1994, 16, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarinci, N.; Worrall, L.; Hickson, L. Factors associated with third-party disability in spouses of older people with hearing impairment. Ear Hear. 2012, 33, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, H.; Moutela, T.; Bunker, C.; Shaw, R. Tinnitus groups: A model of social support and social connectedness from peer interaction. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics N (%) | SOs Completing the CTSOQ (n = 194) | SOs Completing the CTSOQ (n = 63) | SOs NOT Completing the CTSOQ (n = 131) | Difference between the SOs Completing and Not Completing the CTSOQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years ± Standard deviation | 55 ± 14 | 55 ± 15 | 55 ± 13 | t(122.388) = −0.138, p = 0.89 |

| [range] | [18–84] | [19–82] | [18–84] | |

| Gender | X2(1) = 0.66, p = 0.72 | |||

| Male | 100 (52%) | 34 (54%) | 67 (51%) | |

| Female | 94 (48%) | 29 (46%) | 64 (49%) | |

| Relationship | X2(4) = 5.53, p = 0.24 | |||

| Partner | 163 (84%) | 51 (81%) | 112 (85%) | |

| Parent | 3 (2%) | 0 | 3 (2%) | |

| Child | 13 (7%) | 7 (11%) | 6 (5%) | |

| Relative | 9 (4%) | 4 (6%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Friend | 6 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Living together n (%) | X2(1) = 0.42, p = 0.52 | |||

| Yes | 168 (87%) | 56 (89%) | 112 (86%) | |

| No | 26 (13%) | 7 (11%) | 19 (14%) | |

| Presence of tinnitus | X2(1) = 4.13, p = 0.04 | |||

| Yes | 34 (18%) | 6 (9%) | 28 (21%) | |

| No | 160 (82%) | 57 (91%) | 103 (79%) | |

| CTSOQ pre-intervention | t(149.875) = −0.967, p = 0.34 | |||

| Mean score ± Standard deviation | 40.92 ± 17.32 | 39.32 ± 14.75 | 41.69 ± 18.44 | |

| [range] | [3 to 82] | [11 to 76] | [2 to 82] | |

| CTSOQ post-intervention | Not completed | NA | ||

| Mean score ± Standard deviation | 33.83 ± 16.32 | 33.83 ± 16.32 | ||

| [range] | [2 to 69] | [2 to 69] |

| Within Group Comparisons | Between Group Comparisons | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Variables | SOs with Tinnitus (n = 24, 18%) | SOs without Tinnitus (n = 160, 82%) | Group Differences between SO with and without Tinnitus |

| CTSOQ 1 pre-intervention | t(33) = 13.00, p =< 0.001 d = 2.23 [1.59 to 2.86] | t(159) = 30.17, p =< 0.001 d = 2.38 [2.08 to 2.69] | X2(63) = 63.07, p = 0.47 |

| CTSOQ post-intervention | t(5) = 3.57, p = 0.008 d = 1.46 [0.24 to 2.61] | t(56) = 16.19, p =< 0.001 d = 2.16 [1.65 to 2.58] | X2(42) = 51.40, p = 0.15 |

| TFI | t(24) = 7.13, p =< 0.001 d = 1.38 [0.83 to 1.98] | t(159) = 15.40, p =< 0.001 d = 1.36 [1.12 to 1.60] | X2(100) = 113.80, p = 0.16 |

| GAD-7 | t(24) = 5.26, p =< 0.001 d = 1.02 [0.54 to 1.49] | t(125) = 11.47, p =< 0.001 d = 1.02 [0.81 to 1.24] | X2(16) = 5.67, p = 0.99 |

| PHQ-9 | t(24) = 4.38, p =< 0.001 d = 0.86 [0.40 to 1.32] | t(125) = 10.74, p =< 0.001 d = 0.96 [0.74 to 1.17] | X2(17) = 16.80, p = 0.57 |

| ISI | t(24) = 7.22, p =< 0.001 d = 1.43 [0.85 to 1.98] | t(124) = 13.76, p =< 0.001 d = 1.22 [0.99 to 1.45] | X2(22) = 29.38, p = 0.13 |

| Clinical Variables | Individuals with Tinnitus at Baseline (n = 194) | Post-Intervention Score (n = 148) | Effect Size at Post-Intervention | Correlation with the Post-Intervention Score from the Consequences of Tinnitus on Significant Others Questionnaire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Standard Deviation [range] | Mean ± Standard Deviation [range] | Cohen’s d [Confidence Interval] | Pearson’s Correlation | |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) [range] | Cohen’s d [Confidence Interval] | Pearson’s Correlation | ||

| TFI | 55.01 ± 20.32 [7–96] | 29.56 ± 21.45 [0–100] | d = 1.22 [0.99 to 1.46] | r = 0.46, p < 0.001 |

| GAD-7 | 7.11 ± 5.29 [0–21] | 4.17 ± 4.08 [0–21] | d = 0.61 [0.39 to 0.83] | r = 0.37, p = 0.003 |

| PHQ-9 | 7.23 ± 5.47 [0–26] | 4.21 ± 4.44 [0–27] | d = 0.60 [0.38 to 0.82] | r = 0.43, p < 0.001 |

| ISI | 11.3 ± 6.24 [0–27] | 6.96 ± 5.50 [0–28] | d = 0.73 [0.51 to 0.95] | r = 0.43, p < 0.001 |

| TCQ | 43.14 ± 16.16 [2–89] | 29.20 ± 17.01 [0–100] | d = 0.84 [0.62 to 1.77] | r = 0.28, p = 0.03 |

| THS | 6.81 ± 4.55 [0–16] | 4.60 ± 3.70 [0–16] | d = 0.52 [0.31 to 0.74] | r = 0.23, p = 0.08 |

| THS | 1.13 ± 1.31 [0–4] | 0.77 ± 1.05 [0–4] | d = 0.30 [0.08 to 0.51] | r = 0.39, p = 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beukes, E.W.; Andersson, G.; Manchaiah, V. The Indirect Effect of an Internet-Based Intervention on Third-Party Disability for Significant Others of Individuals with Tinnitus. Audiol. Res. 2024, 14, 809-821. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14050068

Beukes EW, Andersson G, Manchaiah V. The Indirect Effect of an Internet-Based Intervention on Third-Party Disability for Significant Others of Individuals with Tinnitus. Audiology Research. 2024; 14(5):809-821. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14050068

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeukes, Eldré W., Gerhard Andersson, and Vinaya Manchaiah. 2024. "The Indirect Effect of an Internet-Based Intervention on Third-Party Disability for Significant Others of Individuals with Tinnitus" Audiology Research 14, no. 5: 809-821. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14050068

APA StyleBeukes, E. W., Andersson, G., & Manchaiah, V. (2024). The Indirect Effect of an Internet-Based Intervention on Third-Party Disability for Significant Others of Individuals with Tinnitus. Audiology Research, 14(5), 809-821. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14050068