Revisiting the Synergistic In Vitro Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Potential of Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Cetrimide in Combination as an Antiseptic and Disinfectant Agent

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Growth Conditions, Media, Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Planktonic Cells

2.3. Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index Determination

2.4. Effect on Biofilm Formation Ability of Micro-Organisms

2.5. Effect on Pre-Formed Biofilms and Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration Determination

2.6. Microscopic Analysis of the Biofilms

2.7. Motility and Congo Red Binding

2.8. Microbial Adhesion to Hydrocarbon (MATH) Assay

2.9. Preparation of the Chlorhexidine and Cetrimide-Based Formulation

2.10. Standards and Guidelines Followed for Assessing Contact Killing

2.11. Flow Cytometry-Based Assay for Anti-Leptospira Activity

3. Results

3.1. The CHG-CTR Combination Exhibited Synergistic Antimicrobial Activity Against P. aeruginosa

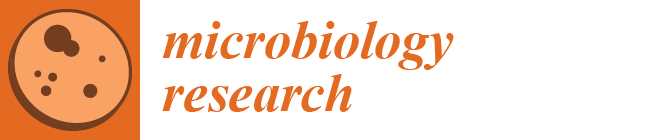

3.2. Effect on Biofilm Formation

3.2.1. The Presence of CHG-CTR Reduced the Adhesion of S. aureus Biofilm on Surfaces

3.2.2. Microscopic Analysis of the S. aureus Biofilms Corroborated the In Vitro Quantitative Analysis

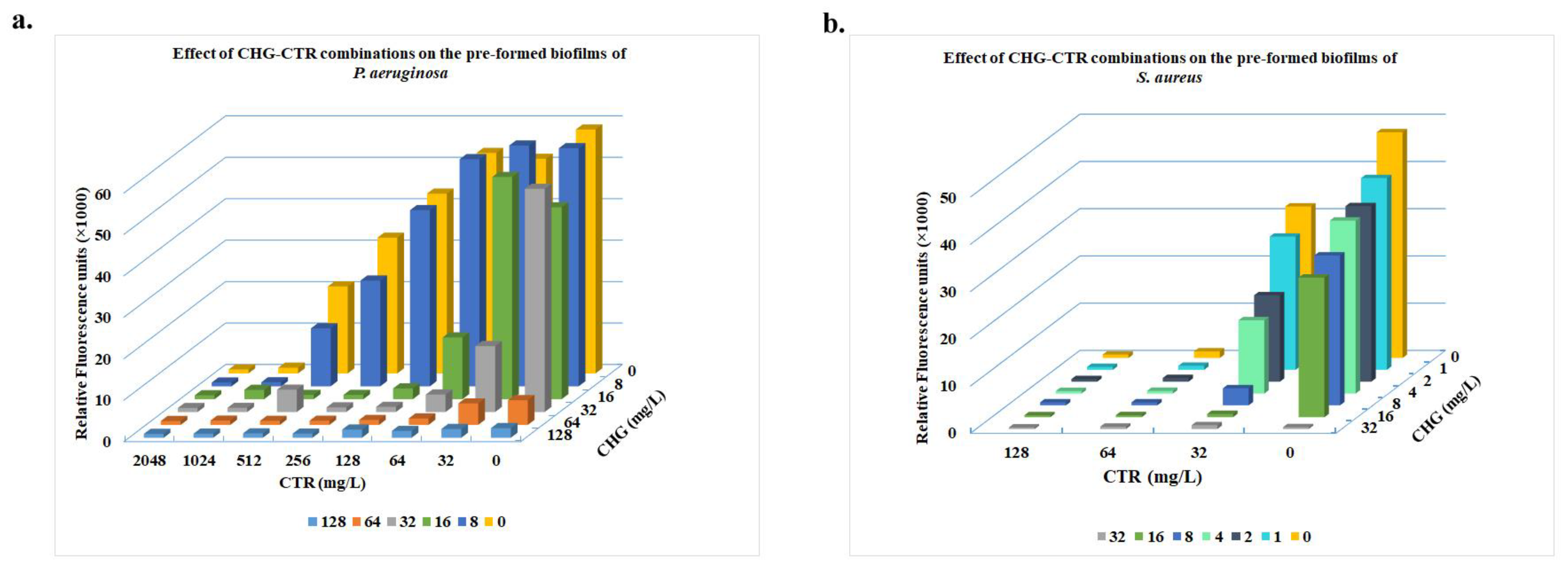

3.3. Effect on the Pre-Formed Biofilms

3.3.1. Treatment with CHG-CTR Led to Reduced Metabolic Activity of Cells Within the Biofilms

3.3.2. CLSM Assessment of the CHG-CTR-Treated Pre-Formed Biofilms of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus

3.3.3. Effect on Cell Surface Hydrophobicity, Motility and Congo Red Binding

3.3.4. Antimicrobial Efficacy of the Formulation

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shineh, G.; Mobaraki, M.; Bappy, M.J.P.; Mills, D.K. Biofilm formation, and related impacts on healthcare, food processing and packaging, industrial manufacturing, marine industries, and sanitation–a review. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 629–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.G.; Motlagh, H.; Povey, S.B.; Percival, S.L. The role of micro-organisms and biofilms in dysfunctional wound healing. In Advanced Wound Repair Therapies; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 39–76. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, R.; Grande, R.; Butrico, L.; Rossi, A.; Settimio, U.F.; Caroleo, B.; Amato, B.; Gallelli, L.; De Franciscis, S. Chronic wound infections: The role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maillard, J.Y.; Pascoe, M. Disinfectants and antiseptics: Mechanisms of action and resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzycki, M.; Drabik, D.; Szostak-Paluch, K.; Hanus-Lorenz, B.; Kraszewski, S. Unraveling the mechanism of octenidine and chlorhexidine on membranes: Does electrostatics matter? Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 3392–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, R.; Robinson, V.H.; Harris, J.; Argyle, S.A.; Nuttall, T.J. A pilot study of the in vitro antimicrobial activity and in vivo residual activity of chlorhexidine and acetic acid/boric acid impregnated cleansing wipes. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, D.L.; McEnery-Stonelake, M. Chlorhexidine: Uses and adverse reactions. Dermatitis 2013, 24, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyeh, B.S.; Dibo, S.A.; Hayek, S.N. Wound cleansing, topical antiseptics and wound healing. Int. Wound J. 2009, 6, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shailaja, S.; Bhat, S.S.; Hegde, S.K. Comparison between the antibacterial efficacies of three root canal irrigating solutions: Antibiotic containing irrigant, Chlorhexidine and Chlorhexidine+ Cetrimide. Oral Health Dent. Manag. 2013, 12, 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Kampf, G.; Kampf, G. Chlorhexidine digluconate. In Antiseptic Stewardship: Biocide Resistance and Clinical Implications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 429–534. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Linares, M.; Ferrer-Luque, C.M.; Arias-Moliz, T.; de Castro, P.; Aguado, B.; Baca, P. Antimicrobial activity of alexidine, chlorhexidine and cetrimide against Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2014, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailón-Sánchez, M.E.; Baca, P.; Ruiz-Linares, M.; Ferrer-Luque, C.M. Antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity of AH plus with chlorhexidine and cetrimide. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 31st ed.; CLSI supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bellio, P.; Fagnani, L.; Nazzicone, L.; Celenza, G. New and simplified method for drug combination studies by checkerboard assay. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatsis-Kavalopoulos, N.; Sánchez-Hevia, D.L.; Andersson, D.I. Beyond the FIC index: The extended information from fractional inhibitory concentrations (FICs). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 2394–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.; Verma, J.; Mallick, S.; Rastogi, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Ghosh, A.S. Absence of the glycosyltransferase WcaJ in Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC13883 affects biofilm formation, increases polymyxin resistance and reduces murine macrophage activation. Microbiology 2019, 165, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceri, H.; Olson, M.E.; Stremick, C.; Read, R.R.; Morck, D.; Buret, A. The Calgary Biofilm Device: New technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 1771–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydorn, A.; Nielsen, A.T.; Hentzer, M.; Sternberg, C.; Givskov, M.; Ersbøll, B.K.; Molin, S. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 2000, 146, 2395–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorregaard, M. Comstat2-A Modern 3D Image Analysis Environment for Biofilms. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- BS: EN 1276: 2009; Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics: Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Bactericidal Activity of Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics Used in Food, Industrial, Domestic and Institutional Areas. Test Method and Requirements. British Standards Institute: London, UK, October 2009.

- BS: EN 1276: 2019; Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Bactericidal Activity of Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics Used in Food, Industrial, Domestic and Institutional Areas—Test Method and Requirements (Phase 2, Step 1). British Standards Institute: London, UK, June 2019.

- BIS: 11479 (Part 2): 2001; BIS: 11479: Antibacterial Toilet Soap- Specification Part 2 Liquid. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, November 2001.

- BS: EN 1656; Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Bactericidal Activity of Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics Used in Veterinary Area—Test Method and Requirements (Phase 2, Step 1); German Version EN 1656:2009. British Standards Institute: London, UK, March 2010.

- BS: EN 14348: 2005; Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Mycobactericidal Activity of Chemical Disinfectants in the Medical Area Including Instrument Disinfectants—Test Methods and Requirements (Phase 2, Step 1). British Standards Institute: London, UK, February 2005.

- BS: EN 1650; Chemical Disinfectants And Antiseptics—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Fungicidal or Yeasticidal Activity of Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics Used in Food, Industrial, Domestic and Institutional Areas—Test Method and Requirements (Phase 2, Step 1). British Standards Institute: London, UK, June 2008.

- BS: EN 1650:2019; Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Fungicidal or Yeasticidal Activity of Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics Used in Food, Industrial, Domestic and Institutional Areas. British Standards Institute: London, UK, August 2019.

- ASTM: E1052-20; Standard Practice to Assess the Activity of Microbicides Against Viruses in Suspension. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM International): West Conshohocken, PA, USA, January 2020.

- BS: EN 14476: 2013 + A1: 2015; Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Virucidal Activity in the Medical Area—Test Method and Requirements (Phase 2/Step 1). British Standards Institute: London, UK, September 2015.

- BS: EN 14476: 2013 + A2: 2019; Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Virucidal Activity in the Medical Area—Test Method and Requirements (Phase 2/Step 1). British Standards Institute: London, UK, July 2019.

- BS: EN 13704: 2002; Chemical Disinfectants—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Sporicidal Activity of Chemical Disinfectants Used in Food, Industrial, Domestic and Institutional Areas—Test Method and Requirements (Phase 2, Step 1). British Standards Institute: London, UK, March 2002.

- Fontana, C.; Crussard, S.; Simon-Dufay, N.; Pialot, D.; Bomchil, N.; Reyes, J. Use of flow cytometry for rapid and accurate enumeration of live pathogenic Leptospira strains. J. Microbiol. Methods 2017, 132, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grare, M.; Dibama, H.M.; Lafosse, S.; Ribon, A.; Mourer, M.; Regnouf-de-Vains, J.B.; Finance, C.; Duval, R.E. Cationic compounds with activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria: Interest of a new compound compared with two older antiseptics, hexamidine and chlorhexidine. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, E.S.; Hasani, A.; Varschochi, M.; Sadeghi, J.; Memar, M.Y. Biocide resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: Appraising the mechanisms. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 117, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, M.; Pereira, M.O.; Vieira, M.J. Effect of mechanical stress on biofilms challenged by different chemicals. Water Res. 2005, 39, 5142–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaei, A. Viral Inactivation with Emphasis on SARS-CoV-2 Using Physical and Chemical Disinfectants. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 9342748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olorode, A.O.; Bamigbola, A.E.; Ogba, M.O. Antimicrobial activities of chlorhexidine gluconate and cetrimide against pathogenic microorganisms isolated from slaughter houses in Rivers State, Nigeria. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 7, 322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Mullany, L.C.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Tielsch, J.M. Safety and impact of chlorhexidine antisepsis interventions for improving neonatal health in developing countries. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2006, 25, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, R.; Dodhia, V.H.; Jeanes, C.; Wade, R.G. Bacterial sensitivity to chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine antiseptics over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis of human-derived data. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koburger, T.; Hübner, N.O.; Braun, M.; Siebert, J.; Kramer, A. Standardized comparison of antiseptic efficacy of triclosan, PVP–iodine, octenidine dihydrochloride, polyhexanide and chlorhexidine digluconate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 1712–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, L.J.; Hind, C.K.; Sutton, J.M.; Wand, M.E. Growth media and assay plate material can impact on the effectiveness of cationic biocides and antibiotics against different bacterial species. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 66, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, V.I.; Lowbury, E.J. Use of an improved cetrimide agar medium and other culture methods for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Pathol. 1965, 18, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Takami, T.; Matsumura, R.; Dorofeev, A.; Hirata, Y.; Nagamune, H. In vitro evaluation of the biocompatibility of newly synthesized bis-quaternary ammonium compounds with spacer structures derived from pentaerythritol or hydroquinone. Biocontrol Sci. 2016, 21, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Moliz, M.T.; Ferrer-Luque, C.M.; González-Rodríguez, M.P.; Valderrama, M.J.; Baca, P. Eradication of Enterococcus faecalis biofilms by cetrimide and chlorhexidine. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishen, A.; Sum, C.P.; Mathew, S.; Lim, C.T. Influence of irrigation regimens on the adherence of Enterococcus faecalis to root canal dentin. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.Z.; Daum, R.S. Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections. In Staphylococcus aureus: Microbiology, Pathology, Immunology, Therapy and Prophylaxis; Curr Top Microbiol Immunol; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 325–383. [Google Scholar]

- Udwadia, F.E. Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome due to tropical infections. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 7, 233. [Google Scholar]

- Endale, H.; Mathewos, M.; Abdeta, D. Potential causes of spread of antimicrobial resistance and preventive measures in one health perspective-a review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 7515–7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, J.N.; Gorman, S.P.; Gilmore, B.F. Clinical relevance of the ESKAPE pathogens. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2013, 11, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, I. Spectrum and treatment of anaerobic infections. J. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.M.; Odell, J.A. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infections. J. Thorac. Dis. 2014, 6, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Fraud, S.; Hann, A.C.; Maillard, J.Y.; Russell, A.D. Effects of ortho-phthalaldehyde, glutaraldehyde and chlorhexidine diacetate on Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus strains with modified permeability. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Higa, N.; Okura, N.; Matsumoto, A.; Hermawan, I.; Yamashiro, T.; Suzuki, T.; Toma, C. Characterizing interactions of Leptospira interrogans with proximal renal tubule epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himani, D.; Suman, M.K.; Mane, B.G. Epidemiology of leptospirosis: An Indian perspective. J. Foodborne Zoonotic Dis. 2013, 1, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Santos, G.C.; Vasconcelos, C.C.; Lopes, A.J.; de Sousa Cartágenes, M.D.; Filho, A.K.; do Nascimento, F.R.; Ramos, R.M.; Pires, E.R.; de Andrade, M.S.; Rocha, F.M.; et al. Candida infections and therapeutic strategies: Mechanisms of action for traditional and alternative agents. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, K.R.; Revie, N.M.; Fu, C.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Treatment strategies for cryptococcal infection: Challenges, advances and future outlook. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meray, Y.; Gençalp, D.; Güran, M. Putting it all together to understand the role of Malassezia spp. in dandruff etiology. Mycopathologia 2018, 183, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P. aeruginosa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICCHG | MICCTR | FICCTR-CHG | FICCHG-CTR | FICI | Interaction |

| 4 | 256 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | Additive |

| 4 | 128 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.75 | Additive |

| 4 | 64 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.625 | Additive |

| 4 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.063 | 0.563 | Additive |

| 4 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.031 | 0.531 | Additive |

| 4 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.516 | Additive |

| 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.008 | 0.508 | Additive |

| 4 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.004 | 0.504 | Additive |

| 2 | 256 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | Additive |

| 2 | 128 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | Additive |

| 2 | 64 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.375 | Synergy |

| 2 | 32 | 0.25 | 0.063 | 0.313 | Synergy |

| 2 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.031 | 0.281 | Synergy |

| 2 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.016 | 0.266 | Synergy |

| 1 | 256 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.625 | Additive |

| 1 | 128 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.375 | Synergy |

| 1 | 64 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | Synergy |

| 1 | 32 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.188 | Synergy |

| 1 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.031 | 0.156 | Synergy |

| 0.5 | 256 | 0.063 | 0.5 | 0.563 | Additive |

| 0.5 | 128 | 0.063 | 0.25 | 0.313 | Synergy |

| 0.5 | 64 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.188 | Synergy |

| 0.5 | 32 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.125 | Synergy |

| 0.25 | 256 | 0.031 | 0.5 | 0.531 | Additive |

| 0.25 | 128 | 0.031 | 0.25 | 0.281 | Synergy |

| 0.25 | 64 | 0.031 | 0.125 | 0.156 | Synergy |

| 0.125 | 256 | 0.016 | 0.500 | 0.516 | Additive |

| 0.125 | 128 | 0.016 | 0.250 | 0.266 | Synergy |

| S. aureus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICCHG | MICCTR | FICCTR-CHG | FICCHG-CTR | FICI | Interaction |

| 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | Additive |

| 0.25 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | Additive |

| 0.125 | 4 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.625 | Additive |

| 0.063 | 4 | 0.063 | 0.5 | 0.563 | Additive |

| 0.031 | 4 | 0.031 | 0.5 | 0.531 | Additive |

| 0.016 | 4 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.516 | Additive |

| 0.008 | 4 | 0.008 | 0.5 | 0.508 | Additive |

| 0.004 | 4 | 0.004 | 0.5 | 0.504 | Additive |

| 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.75 | Additive |

| Micro-Organism | Dilution | Contact Time (min) | Log Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bactericidal activity shown as per BS EN 1276 | |||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 10536 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5 |

| Enterococcus hirae ATCC 10541 # | 1:15 | 1 | >5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 # | 1:15 | 1 | >5 |

| Bactericidal activity shown as per IS 11479 | |||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 10536 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5 |

| Salmonella typhi AB 1468 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6 |

| Salmonella typhi AB 1649 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia NCIM 5215 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.78 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia ATCC 700603 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5.93 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia BAA 2146 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.14 |

| Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3906 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5.77 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 32518 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.39 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.46 |

| Escherichia coli MTCC 448 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.75 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 8739 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.31 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 10536 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.57 |

| Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 14028 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.52 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13048 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.82 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 1166 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.64 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 9844 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.79 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 3219 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.42 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 3223 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.34 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 3232 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.38 |

| Salmonella enterica ATCC 13076 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.75 |

| Salmonella typhi AB 1468 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.31 |

| Salmonella typhi AB 1649 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.43 |

| Shigella flexneri ATCC 12022 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.65 |

| Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 14028 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.52 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 1166 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.64 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 9844 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.79 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 3219 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.42 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 3223 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.34 |

| Salmonella enterica MTCC 3232 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.38 |

| Salmonella enterica ATCC 13076 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.75 |

| Shigella flexneri ATCC 12022 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.65 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13048 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.82 |

| Enterobacter durans MTCC 3031 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.75 |

| Haemophilus influenza ATCC 49247 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.61 |

| Haemophilus paraphrophilus ATCC 49917 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.94 |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae ATCC 7901 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.77 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5.74 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii BAA 1605 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.01 |

| Camphylobacter jejuni ATCC 49301 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.11 |

| Helicobacter pylori ATCC 700392 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5.84 |

| Helicobacter pylori NCTC 11637 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.04 |

| Neisseria meningitides ATCC 13090 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5.93 |

| Prevotella bivia ATCC 29303 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.49 |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis ATCC 13979 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5.74 |

| Serratia marcescens ATCC 14041 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.92 |

| Neisseria meningitides ATCC 13090 * | 1:15 | 1 | >5.93 |

| Haemophilus influenzae ATCC 49247 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.61 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis ATCC 25238 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.56 |

| Bacillus cereus NCIM 2155 # | 1:15 | 1 | >5.9 |

| Streptococcus pneumonia ATCC 12344 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.81 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 700674 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.61 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 35088 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.16 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49150 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.1 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49616 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.03 |

| Corynebacterium diphtheria ATCC 13812 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.61 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.04 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 33591 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.87 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.47 |

| Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 96 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.54 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 700698 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.49 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.72 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538P # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.54 |

| Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 3103 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.64 |

| Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1144 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.75 |

| Corynebacterium striatum MTCC 8963 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.2 |

| Enterococcus faecium ATCC 700221 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.54 |

| Enterococcus faecium ATCC 49624 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.37 |

| Enterococcus faecium ATCC 51558 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.23 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 700570 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.48 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 3086 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.22 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 26936 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.23 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis MTCC 3086 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.11 |

| Actinomyces viscosus MTCC 7435 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.48 |

| Lactococcus latics ATCC 11454 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.58 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 432202 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.58 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes BAA 946 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.75 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes MTCC 1928 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.25 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes MTCC 1924 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.64 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes MTCC 1926 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.37 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes MTCC 1927 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.33 |

| Clostridium perfringens ATCC 13124 # | 1:15 | 1 | >5.85 |

| Clostridium perfringens ATCC 3624 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.62 |

| Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 11437 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.6 |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides MTCC 867 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.69 |

| Finegoldia magna ATCC 29328 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.62 |

| Arthobacter sp MTCC 1726 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.69 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus MTCC 10307 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.86 |

| Bactericidal activity shown against antibiotic-resistant pathogens as per IS 11479 | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoninae ATCC 700674 # (intermediate resistance to penicillin) | 1:15 | 1 | >6.61 |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ATCC 33591 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.87 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (broad spectrum of resistance to various commercial antibiotics) * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.60 |

| Enterococcus fecalis (VRE) # (resistant to Gentamicin and Vancomycin) | 1:15 | 1 | >7.38 |

| Enterococcus fecium (VRE) ATCC 700221 # (resistant to Vancomycin) | 1:15 | 1 | >6.54 |

| Anaerobic microbes shown as per IS 11479 | |||

| Clostridium perfringens ATCC 13124 # | 1:15 | 1 | >5.85 |

| Prevotella bivia ATCC 29303 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.49 |

| Clostridium difficile BAA 1382 #* | 1:15 | 1 | >6.03 |

| Camphylobacter jejuni ATCC 49301 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.11 |

| Clostridium perfringens ATCC 3624 * | 1:15 | 1 | >6.62 |

| Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 11437 #* | 1:15 | 1 | >6.6 |

| Propionibacterium acnes MTCC 1951 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.36 |

| Propionibacterium acnes ATCC 11827 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.91 |

| Propionibacterium acnes MTCC 3297 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.74 |

| Finegoldia magna ATCC 29328 # | 1:15 | 1 | >6.62 |

| Mycobacterium activity shown as per EN 1656 (1999) 1, EN14348 2and IS11479 3 | |||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv 1 | 1:15 | 1 | >4.81 |

| Mycobacterium pheli NCIM 2240 1 | 1:15 | 1 | >4.81 |

| Mycobacterium terrae 2 | - | 60 | >4.51 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis ATCC 607 3 | 1:15 | 1 | >5.95 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis mc 2 155 ATCC 700084 3 | 1:15 | 1 | >6.03 |

| Bactericidal reduction and inactivation of Leptospira interrogans | |||

| Leptospira interrogans * | 1:15 | 5 | >3.0 |

| Sporicidal activity shown as per EN 13704 | |||

| Bacillus subtilis # ATCC 6633 | 1:1 | 60 | >3 |

| Micro-Organism | Dilution | Log Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442 | 1:15 | >6.89 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 10536 | 1:15 | >6.57 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | 1:15 | >6.95 |

| Enterococcus hirae ATCC 10541 | 1:15 | >6.40 |

| Corynebacterium striatum ATCC 6940 | 1:15 | >6.18 |

| Propionibacterium acnes MTCC 1951 | 1:15 | >7.04 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ATCC 3359 | 1:15 | >6.56 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 700674 (penicillin-resistant) | 1:15 | >5.56 |

| Candida albicans ATCC 10231 | 1:15 | >5.28 |

| Micro-Organism | Dilution | Contact Time | Log Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeasticidal/Fungicidal Activity Shown as per IS 11479 | |||

| Cryptococcus albidus ATCC 26902 | 1:15 | 1 | >6.65 |

| Candida krusei ATCC 6258 | 1:15 | 1 | >4.93 |

| Filobasidiella neoformans var. bacillispora (Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii) MTCC 1347/ATCC 32269 | 1:15 | 1 | >5.08 |

| Cryptococcus laurentii MTCC 2898 | 1:15 | 1 | >4.4 |

| Candida albicans ATCC 10231 | 1:15 | 1 | >6.06 |

| Malassezia furfur ATCC 14521 | 1:15 | 1 | 3.02 |

| Malassezia globosa NBRC 101597 | 1:15 | 1 | >4.92 |

| Malassezia restricta ATCC MYA 4611 | 1:15 | 1 | >4.94 |

| Candia albicans NCIM 3102 | 1:15 | 1 | >5.01 |

| Malassezia pachydermatis MTCC 1369 | 1:15 | 1 | >4.61 |

| Yeasticidal Activity Shown as per BS EN 1650 | |||

| Candida albicans ATCC 10231 | 1:15 | 15 | >4 |

| Virus Name | Dilution | Contact Time | Log Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virucidal Activity Shown as per ASTM E1052 1 and EN 14476 2 | |||

| Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 ^,1 | 1:1 | 1 | >4.10 |

| Duck hepatitis B $ virus 1 | 1:1 | 2 | 2 |

| H1N1 influenza A ^ virus 2 | 1:15 | 2 | 1.75 |

| H9N2 ^ (avian flu) 1 | 1:15 | 5 | >4.67 |

| hRSV ^,1 | 1:15 | 5 | 2 |

| Adenovirus $,2 | 1:15 | 5 | 2.17 |

| SARS-CoV-2 ^ (COVID-19 virus) 1 | 1:15 | 2 | ≥ 3.10 |

| Zika ^ virus 1 | 1:1 | 5 | 2 |

| Monkeypox virus $,1 | 1:15 | 5 | >4.42 |

| Murine coronavirus ^,2 | 1:15 | 2 | >4 |

| Murine norovirus ^,2 | 1:15 | 5 | 2.67 |

| Simian rotavirus ^,2 | 1:15 | 1 | >4.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jain, D.; Gupta, R.; Mehta, R.; Prabhakaran, P.N.; Kumari, D.; Bhui, K.; Murali, D. Revisiting the Synergistic In Vitro Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Potential of Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Cetrimide in Combination as an Antiseptic and Disinfectant Agent. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16010016

Jain D, Gupta R, Mehta R, Prabhakaran PN, Kumari D, Bhui K, Murali D. Revisiting the Synergistic In Vitro Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Potential of Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Cetrimide in Combination as an Antiseptic and Disinfectant Agent. Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleJain, Diamond, Rimjhim Gupta, Rashmi Mehta, Pratheesh N. Prabhakaran, Deva Kumari, Kulpreet Bhui, and Deepa Murali. 2025. "Revisiting the Synergistic In Vitro Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Potential of Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Cetrimide in Combination as an Antiseptic and Disinfectant Agent" Microbiology Research 16, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16010016

APA StyleJain, D., Gupta, R., Mehta, R., Prabhakaran, P. N., Kumari, D., Bhui, K., & Murali, D. (2025). Revisiting the Synergistic In Vitro Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Potential of Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Cetrimide in Combination as an Antiseptic and Disinfectant Agent. Microbiology Research, 16(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16010016