Therapeutic Needs of Older Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

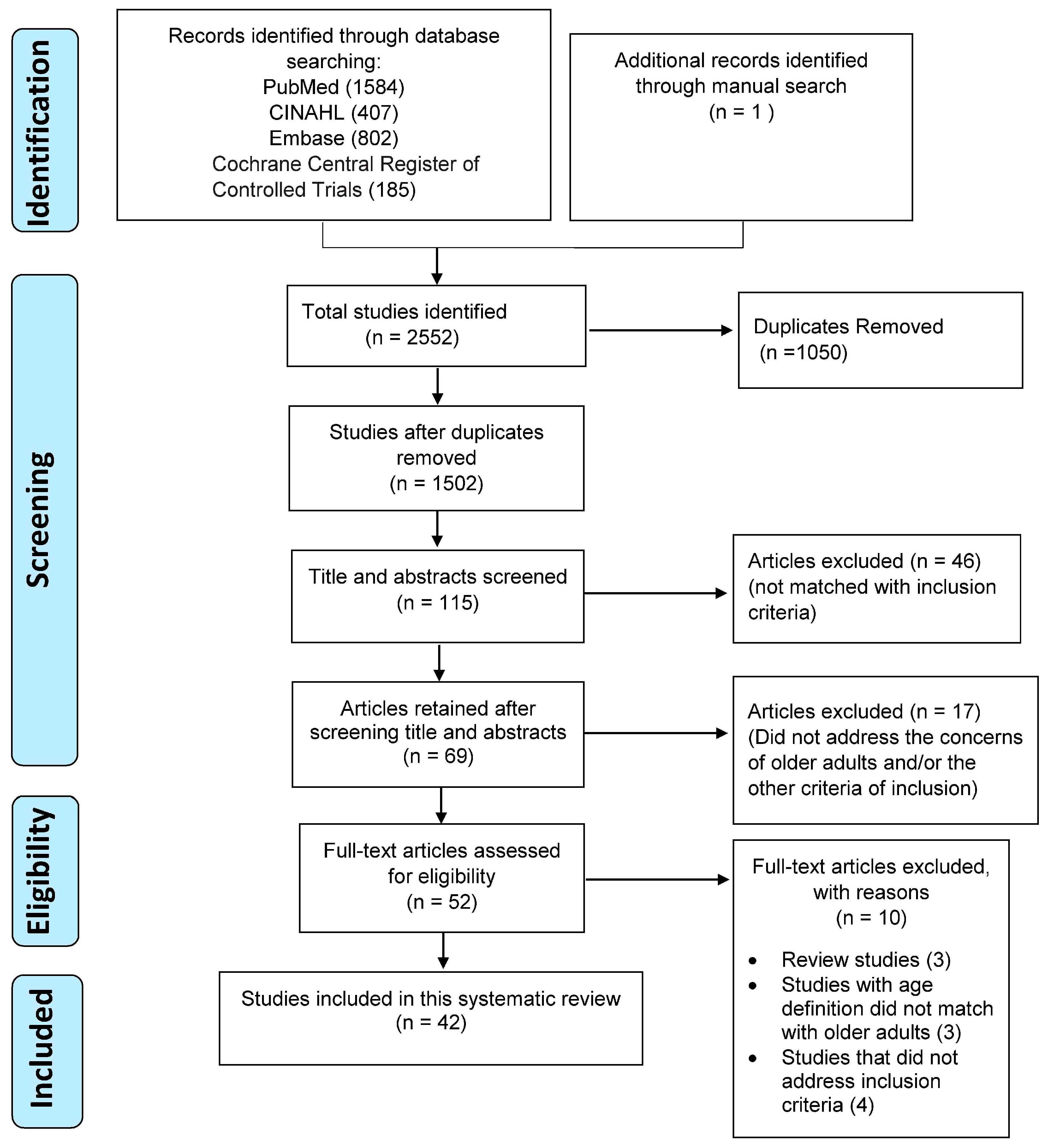

2. Methods

2.1. Search Method

2.2. Study Selection Criteria

2.3. Quality Appraisal

2.4. Data Abstraction

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Quality of Life

3.3. Symptom Presentation

3.3.1. IBD-Related Symptoms

3.3.2. Geriatric Concerns

3.4. IBD Medication Utilization Patterns

3.4.1. Biologics

3.4.2. Immunosuppressant Medications

3.4.3. 5-Aminosalicylic Acids (5-ASA) and Steroids

3.5. Surgical Outcomes

3.6. Healthcare Utilization

3.7. Mental Health Concerns

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/features/IBD-more-chronic-diseases.html (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Nguyen, G.C.; Bernstein, C.N. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Elderly Patients: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taleban, S.; Colombel, J.F.; Mohler, M.J.; Fain, M.J. Inflammatory bowel disease and the elderly: A review. J. Crohns Colitis 2015, 9, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Suparan, K.; Arayakarnkul, S.; Jaroenlapnopparat, A.; Polpichai, N.; Fangsaard, P.; Kongarin, S.; Srisurapanont, K.; Sukphutanan, B.; Wanchaitanawong, W.; et al. Global Epidemiology and Burden of Elderly-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Decade in Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieujean, S.; Caron, B.; Jairath, V.; Benetos, A.; Danese, S.; Louis, E.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Is it time to include older adults in inflammatory bowel disease trials? A call for action. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochar, B.; Kalasapudi, L.; Ufere, N.N.; Nipp, R.D.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Ritchie, C.S. Systematic Review of Inclusion and Analysis of Older Adults in Randomized Controlled Trials of Medications Used to Treat Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 1541–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velonias, G.; Conway, G.; Andrews, E.; Garber, J.J.; Khalili, H.; Yajnik, V.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Older Age- and Health-related Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, I.; Rogler, G.; Halfvarson, J. The Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Elderly: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2018, 2, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.; Bertani, L.; Rodrigues, C. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly: A review. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Katz, S. The elderly IBD patient in the modern era: Changing paradigms in risk stratification and therapeutic management. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 17562848211023399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melmed, G.Y.; Oliver, B.; Hou, J.K.; Lum, D.; Singh, S.; Crate, D.; Almario, C.; Bray, H.; Bresee, C.; Gerich, M.; et al. Quality of care program reduces unplanned health care utilization in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 2410–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software [Internet]. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Katz, S.; Feldstein, R. Inflammatory bowel disease of the elderly: A wake-up call. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 4, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tao, Z.; Feng, Q.; Lisa, F. Quality of life and influencing factors in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World Chin. J. Dig. 2014, 23, 823–827. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M.D.; Kappelman, M.D.; Martin, C.F.; Chen, W.; Anton, K.; Sandler, R.S. Risk factors for depression in the elderly inflammatory bowel disease population. J. Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, G.C.; Sheng, L.; Benchimol, E.I. Health Care utilization in elderly onset inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Sandborn, W.J.; Singh, S. Infections and cardiovascular complications are common causes for hospitalization in older patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Older Persons [Internet]. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2024. Available online: https://emergency.unhcr.org/protection/persons-risk/older-persons (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Munn, Z.; Stone, J.C.; Aromataris, E.; Klugar, M.; Sears, K.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Barker, T.H. Assessing the risk of bias of quantitative analytical studies: Introducing the vision for critical appraisal within JBI systematic reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adar, T.; Faleck, D.; Sasidharan, S.; Cushing, K.; Borren, N.Z.; Nalagatla, N.; Ungaro, R.; Sy, W.; Owen, S.C.; Patel, A.; et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor α antagonists and vedolizumab in elderly IBD patients: A multicentre study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 49, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakis, C.; Saxena, S.; Chhaya, V.; Cecil, E.; Curcin, V.; Pollok, R. Do thiopurines reduce the risk of surgery in elderly onset inflammatory bowel disease? A 20-year national population-based cohort study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, T.; Shinzaki, S.; Asakura, A.; Tashiro, T.; Tani, M.; Otake, Y.; Yoshihara, T.; Iwatani, S.; Yamada, T.; Sakakibara, Y.; et al. Elderly onset age is associated with low efficacy of first anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asscher, V.E.R.; Waars, S.N.; van der Meulen-de Jong, A.E.; Stuyt, R.J.L.; Baven-Pronk, A.M.C.; van der Marel, S.; Jacobs, R.J.; Haans, J.J.L.; Meijer, L.J.; Klijnsma-Slagboom, J.D.; et al. Deficits in geriatric assessment associate with disease activity and burden in older patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, e1006–e1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Cook, S.F.; Erichsen, R.; Long, M.D.; Bernstein, C.N.; Wong, J.; Carroll, C.F.; Frøslev, T.; Sampson, T.; Kappelman, M.D. International variation in medication prescription rates among elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollegala, N.; Jackson, T.D.; Nguyen, G.C. Increased postoperative mortality and complications among elderly patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: An analysis of the national surgical quality improvement program cohort. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozon, A.; Nancey, S.; Serrero, M.; Caillo, L.; Gilletta, C.; Benezech, A.; Combes, R.; Danan, G.; Akouete, S.; Pages, L.; et al. Risk of infection in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease under biologics: A prospective, multicenter, observational, one-year follow-up comparative study. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2023, 47, 102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas-Deza, D.; Lamuela-Calvo, L.J.; Gomollón, F.; Arbonés-Mainar, J.M.; Caballol, B.; Gisbert, J.P.; Rivero, M.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, E.; Arias García, L.; Gutiérrez Casbas, A.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of Ustekinumab in elderly patients with Crohn’s disease: Real world evidence from the ENEIDA registry. J. Crohns Colitis 2023, 17, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, C.; Salleron, J.; Savoye, G.; Fumery, M.; Merle, V.; Laberenne, J.E.; Vasseur, F.; Dupas, J.L.; Cortot, A.; Dauchet, L.; et al. Natural history of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based cohort study. Gut 2014, 63, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Kochar, B.; Cai, T.; Ritchie, C.S.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Comorbidity influences the comparative safety of biologic therapy in older adults with inflammatory bowel diseases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 1845–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.A.; Plevris, N.; Kopylov, U.; Grinman, A.; Ungar, B.; Yanai, H.; Leibovitzh, H.; Isakov, N.F.; Hirsch, A.; Ritter, E.; et al. Vedolizumab is effective and safe in elderly inflammatory bowel disease patients: A binational, multicenter, retrospective cohort study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2020, 8, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.E.; Smits, L.J.T.; van Ruijven, B.; den Broeder, N.; Russel, M.G.V.M.; Römkens, T.E.H.; West, R.L.; Jansen, J.M.; Hoentjen, F. Increased discontinuation rates of anti-TNF therapy in elderly inflammatory bowel disease patients. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Zator, Z.A.; de Silva, P.; Nguyen, D.D.; Korzenik, J.; Yajnik, V.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Older age is associated with higher rate of discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everhov, Å.H.; Halfvarson, J.; Myrelid, P.; Sachs, M.C.; Nordenvall, C.; Söderling, J.; Ekbom, A.; Neovius, M.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Askling, J.; et al. Incidence and treatment of patients diagnosed with inflammatory bowel diseases at 60 years or older in Sweden. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 518–528.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumery, M.; Pariente, B.; Sarter, H.; Charpentier, C.; Armengol Debeir, L.; Dupas, J.L.; Coevoet, H.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; dʼAgay, L.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; et al. Natural history of crohn’s disease in elderly patients diagnosed over the age of 70 Years: A population-based study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1698–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.; Aggarwal, M.; Butler, R.; Achkar, J.P.; Lashner, B.; Philpott, J.; Cohen, B.; Qazi, T.; Rieder, F.; Regueiro, M.; et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of Ustekinumab in elderly Crohn’s disease patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 3138–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebeyehu, G.G.; Fiske, J.; Liu, E.; Limdi, J.K.; Broglio, G.; Selinger, C.; Razsanskaite, V.; Smith, P.J.; Flanagan, P.K.; Subramanian, S. Ustekinumab and Vedolizumab are equally safe and effective in elderly Crohn’s disease patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, G.D.; LeBlanc, J.F.; Golovics, P.A.; Wetwittayakhlang, P.; Qatomah, A.; Wang, A.; Boodaghians, L.; Liu Chen Kiow, J.; Al Ali, M.; Wild, G.; et al. Effectiveness, safety, and drug sustainability of biologics in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A retrospective study. World, J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4823–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.K.; Feagins, L.A.; Waljee, A.K. Characteristics and behavior of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: A multi-center US study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 2200–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, J.M.; Iborra, M.; Bosca-Watts, M.M.; Maroto, N.; Gil, R.; Cortes, X.; Hervás, D.; Paredes, J.M. Inflammatory bowel disease in patients over the age of 70 y. Does the disease duration influence its behavior? Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, S.F.; van den Heuvel, T.R.; Zeegers, M.P.; Hameeteman, W.H.; Romberg-Camps, M.J.; Oostenbrug, L.E.; Masclee, A.A.; Jonkers, D.M.; Pierik, M.J. Epidemiology and long-term outcome of inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed at elderly age-an increasing distinct entity? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, M.; Baidoo, L.; Schwartz, M.B.; Barrie, A., 3rd; Regueiro, M.; Dunn, M.; Binion, D.G. Geriatric inflammatory bowel disease: Phenotypic presentation, treatment patterns, nutritional status, outcomes, and comorbidity. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 2408–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Pernes, T.; Weiss, A.; Trivedi, C.; Patel, M.; Medvedeva, E.; Xie, D.; Yang, Y.-X. Efficacy of Vedolizumab in a nationwide cohort of elderly inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzig, M.E.; Stukel, T.A.; Kaplan, G.G.; Murthy, S.K.; Nguyen, G.C.; Talarico, R.; Benchimol, E.I. Variation in care of patients with elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cohort study. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2020, 4, e16–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Na, M.J.; Ye, B.D.; Cheon, J.H.; Im, J.P.; Kim, J.S.; CONNECT Study Group. Clinical characteristics of Korean patients with elderly-onset Crohn’s disease: Results from the prospective connect study. Gut Liver 2022, 16, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochar, B.; Jylhävä, J.; Söderling, J.; Ritchie, C.S.; SWIBREG Study Group; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Khalili, H.; Olén, O. Prevalence and implications of frailty in older adults with incident inflammatory bowel diseases: A Nationwide cohort study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2358–2365.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobatón, T.; Ferrante, M.; Rutgeerts, P.; Ballet, V.; Van Assche, G.; Vermeire, S. Efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapy in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosli, M.H.; Alghamdi, M.K.; Bokhary, O.A.; Alzahrani, M.A.; Takieddin, S.Z.; Galai, T.A.; Alsahafi, M.A.; Saadah, O.I. Inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly: A focus on disease characteristics and treatment patterns. Saudi, J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.C.; Bernstein, C.N.; Benchimol, E.I. Risk of surgery and mortality in elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based cohort study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, L.P.; Bhandari, S.; Liu, R.; Guilday, C.; Zadvornova, Y.; Saeian, K.; Eastwood, D. Advanced age does not negatively impact health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 1787–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, D.; Privitera, G.; Crispino, F.; Mezzina, N.; Castiglione, F.; Fiorino, G.; Laterza, L.; Viola, A.; Bertani, L.; Caprioli, F.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in a matched cohort of elderly and nonelderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease: The IG-IBD LIVE study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 56, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozich, J.J.; Luo, J.; Dulai, P.S. Disease- and treatment-related complications in older patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: Comparison of adult-onset vs elderly-onset disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusher, A.; Araka, E.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Ritchie, C.; Kochar, B. IBD Is Like a Tree: Reflections From Older Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, izae139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashi, P.; Gopalakrishnan, D.; Parikh, M.P.; Shen, B.; Kochhar, G. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A matched case-control study. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 8, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, J.; Stein, D.J.; Lipcsey, M.; Li, B.; Feuerstein, J.D. High rates of mortality in geriatric patients admitted for inflammatory bowel disease management. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2022, 56, e20–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Qian, J. The incidence rate and risk factors of malignancy in elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: A Chinese cohort study from 1998 to 2020. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 788980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.; D’Arcy, M.; Barnes, E.L.; Freedman, N.D.; Engels, E.A.; Song, M. Associations of inflammatory bowel disease and subsequent cancers in a population-based study of older adults in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2022, 6, pkab096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Council of Aging [Internet]. Get the Facts on Healthy Aging. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncoa.org/article/get-the-facts-on-healthy-aging (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Khan, S.; Sebastian, S.A.; Parmar, M.P.; Ghadge, N.; Padda, I.; Keshta, A.S.; Minhaz, N.; Patel, A. Factors influencing the quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: A comprehensive review. Dis. Mon. 2024, 70, 101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, K.; Holmstrom, A.; Luo, Z.; Wyatt, G.; Given, B. Factors Influencing Received Social Support Among Emerging Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2020, 43, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Cho, H.J.; Cho, S.; Ryu, J.; Kim, S. The Moderating Effect of Social Support between Loneliness and Depression: Differences between the Young-Old and the Old-Old. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, P.; Niezgódka, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I.; Stawczyk-Eder, K.; Banasik, E.; Dobrowolska, A. Dietary Support in Elderly Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Lv, B.; Huang, X.; Liang, X. Advancements in malnutrition in elderly inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gastroenterol. Endosc. 2023, 1, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year, and Setting | Study Type/Design | Age of Elderly | Study Purpose | Variables and Measures | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adar et al., 2019 [22] USA | Retrospective cohort study using EMR data from three hospitals | >60 years of age | To evaluate the effectiveness of two groups of biologics (anti-TNF vs. Vedolizumab) as well as to evaluate their risk of malignancy and infection in in adults >60 years of age |

|

|

| Alexakis et al., 2017 [23] UK | Retrospective cohort study using a national database | >60 years of age | To compare the surgical risk between elderly and adult onset IBD and to analyze the effect of thiopurines on surgical outcomes |

|

|

| Amano et al., 2022 [24] Japan | Retrospective cohort study study | >60 years of age | To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of anti-TNF therapy and analyzed the factors that influenced anti-TNF’s effectiveness among the elderly onset IBD patients who never received biologics in the past |

|

|

| Asscher et al., 2022 [25] Netherlands | Prospective cohort study | >65 years Old | To evaluate the geriatric deficits in older patients with IBD and to match these deficits with disease characteristics |

|

|

| Benchimol et al., 2013 [26] UK, Canada, US, and Denmark | Retrospective study using health administrative databases from 2004 to 2009 | ≥65 years of age | To identify the prescription variations among elderly adults with IBD | The rate of prescription was assessed for each of the IBD medications (ASA, SASP, systemic and topical steroids, immunosuppressives, and biologics) |

|

| Bollegala et al., 2016 [27] USA | Case-control study using ACS-NSQIP database from 2005 to 2012 | ≥65 years | To compare the post-operative complications and death between elderly IBD patients vs. IBD patients who were <65 years of age |

|

|

| Bozon et al., 2023 [28] France | Prospective, multicenter, cohort observational study | >65 years of age | To identify the infection risk among older adults with IBD who have been placed on biologics (anti-tNF vs. Vedolizumab [VDZ], vs. Ustekinumab [UST]) |

|

|

| Casas-Deza et al., 2023 [29] Spain | Observational multicenter prospective study using registry data | >60 years of age | To evaluate the safety and effectiveness of Ustekinumab (UST)among elderly vs. non-elderly CD patients |

|

|

| Charpentier et al., 2014 [30] France | Retrospective population based study | >60 years of age | To determine the natural history of IBD in individuals who are >60 years of age versus <60 years |

|

|

| Cheng et al., 2022 [31] USA | Retrospective cohort study using national administrative claims database | Patients with IBD who are >60 years of age | To assess the infection risk of different biologics such as anti-TNF agents, Vedolizumab (VDZ)and Ustekinumab (UST) in older adults with IBD |

|

|

| Cohen et al., 2020 [32] Israel and UK | Retrospective multicenter cohort study using patient’s electronic medical records | >60 years of age | To evaluate the effectiveness and adverse effects of Vedolizumab between individuals diagnosed with IBD who are >60 years of age versus <60 years |

|

|

| de Jong et al., 2020 [33] Netherlands | Retrospective cohort study using data from an IBD registry | >60 years of age | To analyze the rates of failure and safety of the initial anti-TNF treatment among individuals with IBD who belong to three different age categories (<40, 40–59, and ≥ 60 years of age) |

|

|

| Desai et al., 2013 [34] USA | Retrospective Case-control study at a single center using medical data | >60 years of age | To evaluate the safety and durability of anti-TNF α (Inflimab, Adalimumab, Certolizumab) among elderly IBD patients |

|

|

| Everhov et al., 2018 [35] Sweden | Retrospective cohort study using national data | ≥60 years of age | To analyze the clinical characteristic and treatment of IBD among elderly adults with IBD and to match surgical rate and healthcare utilization to general population. |

|

|

| Fumery et al., 2016 [36] France | Retrospective study using a population-based registry (1988–2006) | >60 years of age | To evaluate the natural history of CD for those who were diagnosed at the age of 70 vs. who were diagnosed between 60 and 70 years of age |

|

|

| Garg et al., 2022 [37] USA | Retrospective cohort study | >65 years of age | To evaluate the adverse effects and effectiveness of Ustekinumab (UST) in older vs. younger CD patients |

|

|

| Gebeyehu et al., 2023 [38] UK | Multicenter Prospective cohort study | ≥60 years | To evaluate the adverse effects and effectiveness of Ustekinumab and Vedolizumab among older patients with CD |

|

|

| Hahn et al., 2022 [39] Canada | Retrospective study using EMR data | ≥60 years | To assess adverse effects and effectiveness of of biologics (vedolizumab, Adalimumab, Infliximab, and Ustekinumab)among elderly adults with IBD to evaluate the sustainable use of biologics |

|

|

| Hou et al., 2016 [40] USA | Retrospective cohort study at multiple centers | >65 years of age | To compare the nature of the disease behavior and characteristics of IBD among those who were diagnosed after the age of 65 vs. those who were diagnosed between 18 and 64 years of age |

|

|

| Huguet et al., 2018 [41] Spain | Cross sectional study using retrospective data from hospital medical records | >70 Years of age | To evaluate the clinical course, adverse effects of treatment, and the surgical need for elderly IBD patients |

|

|

| Jeuring et al., 2016 [42] Netherlands | Retrospective cohort study | >60 years of age | To determine the incidence and long term effects of IBD on those who have had an IBD diagnosis at 60 years or older and to compare it with those who have had an IBD diagnosis as an adult |

|

|

| Juneja et al., 2012 [43] USA | Retrospective observational study using EMR data | ≥65 years of age | To identify the clinical presentation, treatment models, patient outcomes, comorbidity and nutritional status in older adults with IBD |

|

|

| Khan et al., 2022 [44] USA | Retrospective study using national data from Veterans Health System | >60 years of age | To assess the efficacy of Vedolizumab among older IBD patients and to compare it with younger IBD patients |

|

|

| Kuenzig et al., 2020 [45] Canada | Retrospective cohort study | ≥65 years of age n =4806 | To identify if care variation existed among elderly onset IBD patients and to evaluate the outcomes based on care provided by the specialists (gastroenterologists) vs. primary care providers |

|

|

| Kim et al., 2022 [46] Korea | Prospective study using the data from Crohn’s Disease Clinical Network and Cohort study | >60 years of age | To describe the outcomes and nature of the disease of EO- CD and to compare it with AO- CD |

|

|

| Kochar et al., 2022 [47] Sweden | Retrospective study using national data from a Swedish registry | ≥60 years of age | To assess the frailty rate of older adults who have a diagnosis of IBD and to compare it with younger IBD patients |

|

|

| Long et al., 2014 [17] USA | Prospective study | ≥65 years of age | To determine the association of depression with QOL, disease activity, and medication adherence |

|

|

| Lobaton et al., 2015 [48] Belgium | Retrospective observational case- control study | >65 years of age | To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of anti-TNF among older adults with IBD (>65 years of age) vs. controls (<65 years of age) |

|

|

| Mosli et al. 2023 [49] Saudi Arabia | Retrospective study | >60 Years of age | To assess the clinical characteristics, demograogic and treatment plans of elderly adults with IBD |

|

|

| Nguyen et al., 2015 [18] Canada | Retrospective cohort study using health administrative database | ≥65 years of age | To compare the health services use (hospitalizations, emergency department visits and outpatient visits) among IBD patients with three age groups: 18–40 years old, 41–64 years old and ≥65 years old |

|

|

| Nguyen et al., 2017 [50] Canada | Retrospective cohort study using administrative data | ≥65 years | To compare the dangers of IBD-related surgery and mortality between elderly onset vs. younger-onset IBD |

|

|

| Nguyen et al., 2018 [19] USA | Retrospective cohort study using nationwide readmissions database | >64 years of age | To compare the costs, annual burden, and causes for hospitalization between older (>64 years) and younger (<64 years) IBD patients |

|

|

| Perera et al., 2018 [51] Canada | Retrospective study of a single center | ≥65 years | To assess the relationship between age of IBD diagnosis, advanced age, and HRQOL in elderly adults with IBD and to examine the health predictors of the HRQoL among all age groups |

|

|

| Pugliese et al., 2022 [52] Italy | Matched cohort l retrospective prospective study | ≥65 years | Compared the effectiveness of Vedolizumab among older vs. younger IBD patients |

|

|

| Rozich, et al. 2021 [53] USA | Retrospective EMR cohort study | >60 years of age | Comparative study to assess the complications related to IBD and its treatment in older adults with elderly vs. adult onset IBD |

|

|

| Rusher et al., 2024 [54] USA | Qualitative study | >60 years of age | Qualitative study to evaluate the lived experiences of older adults with IBD |

|

|

| Shashi et al., 2019 [55] USA | Retrospective case-control study using electronic medical record data | ≥65 years of age | To compare the effectiveness (based on healing of the intestinal mucosa and the necessity to have surgical management for IBD) and the toxicities of Vedolizumab among individuals with IBD who were ≥ 65 years vs. who were ≤ 65 years |

|

|

| Schwartz et al., 2022 [56] USA | Retrospective study using a national data | ≥65 | To assess the in-patient mortality, length of stay and total expenditure among elderly adults with IBD |

|

|

| Tao et al., 2014 [16] | Case-control design | >60 years | To assess the QOL of life of older adults with IBD to identify its influencing factors |

|

|

| Velonias et al., 2017 [7] USA | Prospective cohort study at a single center | >60 years of age | To describe the HRQOL in older patients and to compare it between older vs. younger populations (<60 years) |

|

|

| Wang et al., 2021 [57] China | Retrospective cohort study using cancer registry database, telephone follow-up records, and medical documents | ≥60 years of age | To compare incidence trends of malignancy among E-O vs. A-O IBD |

|

|

| Wang et al., 2022 [58] USA | Case–control study using Medicare data | >66 years | To evaluate the association between IBD and cancer in older adults |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davis, S.P.; McInerney, R.; Fisher, S.; Davis, B.L. Therapeutic Needs of Older Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): A Systematic Review. Gastroenterol. Insights 2024, 15, 835-864. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent15030059

Davis SP, McInerney R, Fisher S, Davis BL. Therapeutic Needs of Older Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology Insights. 2024; 15(3):835-864. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent15030059

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavis, Suja P., Rachel McInerney, Stephanie Fisher, and Bethany Lynn Davis. 2024. "Therapeutic Needs of Older Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): A Systematic Review" Gastroenterology Insights 15, no. 3: 835-864. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent15030059

APA StyleDavis, S. P., McInerney, R., Fisher, S., & Davis, B. L. (2024). Therapeutic Needs of Older Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology Insights, 15(3), 835-864. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent15030059