How Patients Can Contribute to the Assessments of Health Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients Defining Their Unmet Needs

2.1. The Case of People Living with HIV and Growth Hormone

2.2. The Case of Children Living with Prader–Willi Syndrome and Growth Hormone

2.3. The Case of End-Stage Heart Disease, an Implantable Heart Device, and Transhumanism

2.4. Highly Organised Networks Needed

- Underserved or Neglected Diseases Some rare diseases receive limited research attention, with no products in development. It is estimated that only around 5% of rare diseases have an FDA-approved drug and up to 15% of rare diseases have at least one drug that shows promise in treatment, diagnosis, or prevention [8]. This means that for the vast majority of rare diseases, no specific product has reached Phase II/III clinical trials.

- Diseases with Limited Treatment Options Even when treatments exist, their effectiveness may be partial or insufficient as not all patients respond to available therapies, treatments may improve some symptoms but not others and side effects or poor tolerability may limit their use. Consequently, many patients still require more effective or safer treatments.

3. Horizon Scanning: Which Products Are Priority?

- Funding research projects directly,

- Organising interdisciplinary scientific discussions with researchers,

- Reviewing the literature to identify research projects aligned with their interests,

- Attending scientific conferences to stay informed about advancements,

- Subscribing to bulletins from learned societies and professional networks.

Patient Groups Can Identify Breakthrough Products up to Five Years Before Their Authorisation

- 9 were authorised,

- 8 were discontinued during the R&D phase, and

- 1 was opposed by advocates, who successfully recommended against its authorisation at an FDA public hearing.

4. Scientific Advice

4.1. One Best Practice: Community Advisory Boards (CABs)

- Development strategy: Should clinical trials focus on recently diagnosed patients or those with late-stage disease?

- Trial design: Selection of comparators, endpoints, and practical trial organisation.

- Trial conduct: Input on substantial amendments, communication of unexpected side effects, trial termination, and dissemination of results.

- Compassionate use programmes: Organisation and access policies.

- Pricing and reimbursement strategies.

- Exclusion criteria, which define the trial population (with potential implications for the P in PICO—Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome).

- Use of secondary endpoints, which can influence the O in PICO [12].

- The Cystic Fibrosis (CF) CAB, established in 2016, initially focused on the R&D of CFTR modulators (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators). These drugs have since transformed the course of the disease for many patients [13]. However, the prevalence of genetic profiles compatible with these treatments varies globally. Future research must now prioritise patients with different genetic mutations who do not benefit from current therapies.

- HIV CAB priorities have evolved over time:

- ○

- In the 1990s, the focus was on developing highly active antiretrovirals (HAART) to combat the HIV epidemic.

- ○

- Today, priorities include long-acting injectable treatments (administered every six months) to improve lifelong adherence.

- Selection of participating countries to ensure representative subgroup analyses.

- Adequate participant numbers to account for diverse treatment backgrounds.

4.2. What Engaging with Patients Entails

- Accepting New Constraints

- Accepting the time it takes: Discussions with patients—even well-trained advocates—require more time than scientific advice provided by regulators or HTA experts. For example, a first meeting with a developer may last an entire day to ensure patient advocates fully understand both the product and the clinical trial design.

- Embracing unpredictable discussions: Unlike structured scientific consultations, patient discussions can take unexpected directions. Patients may raise issues beyond the developer’s prepared questions, reflecting their broader concerns and lived experiences.

- Acknowledging diverse backgrounds: Patients in the room may not always have a scientific background, which necessitates clear communication and patience to ensure mutual understanding.

- Recognising their broader networks: Patients often consult with other stakeholders (e.g., carers, advocacy groups), which can introduce additional perspectives and complexities into discussions.

- 2.

- Preparing for Patient-Centred Dialogues

- Co-constructed agendas: Agendas for meetings are prepared collaboratively between developers/sponsors and patient groups (e.g., Community Advisory Boards or CABs). This ensures that patient priorities are included alongside the developer’s questions.

- Two-way dialogue: Unlike traditional scientific advice, patient engagement is a bidirectional process. Patients are free to raise any topic relevant to them, even if it diverges from the developer’s original agenda. For example:

- ○

- If a developer proposes a technology for a small patient niche, patients may initiate discussions on pricing policies—even if this topic was not originally planned.

- ○

- Questions may extend beyond scientific details to include ethical, practical, or access-related concerns.

- 3.

- Practical Considerations for Effective Engagement

- Language barriers: Finding patient advocates who can understand and express themselves in English (or the working language) can be challenging.

- Preparation time: Adequate time is needed to prepare advocates—ensuring they are informed about the product, trial design, and broader context.

- Inclusivity: Methods of engagement should accommodate diverse levels of expertise and ensure that all voices are heard.

- 4

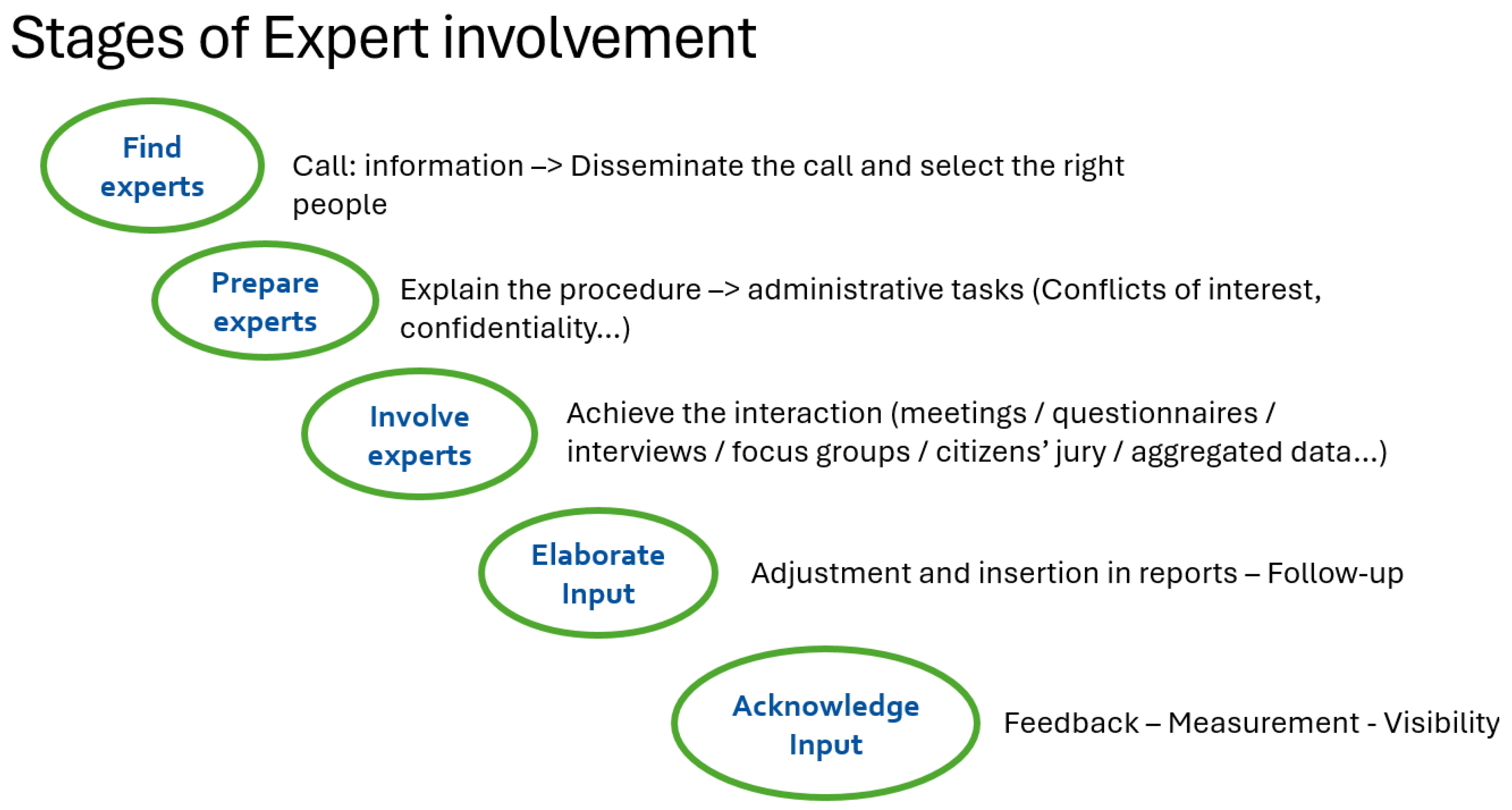

- Key Steps for Patient Engagement

- Developer discussions (e.g., trial design, pricing).

- Scientific advice (e.g., regulatory or HTA consultations).

- Scientific evaluations (e.g., assessments of clinical or economic evidence).

- Rich, real-world insights that scientific experts alone may overlook.

- Greater alignment between developed technologies and patient needs.

- Enhanced trust and transparency in the development process.

- Contributions are meaningful and well-informed,

- Patients feel valued and respected,

- Decisions reflect real-world patient needs and priorities.

5. Assessment and Appraisal

5.1. Ensuring Transparency, Building Trust: Patients Witnessing HTA

5.2. Patients as Active Contributors of an HTA and Data They Could Submit

5.3. Relevant Patient Outcomes: Relevant, from Whose Perspective?

- Minimum Acceptable Benefit: Patients can specify the minimum treatment effect (e.g., improvement in progression-free survival) required to offset adverse reactions or treatment constraints.

- Risk-Benefit Trade-offs: Studies can reveal how patients weigh risks against benefits, such as accepting certain side effects for improved efficacy or quality of life.

- Comparative Assessments: Patients can compare new treatments against placebos or existing therapies, providing insights into which outcomes they prioritise (e.g., survival vs. quality of life vs. convenience).

5.4. Appraisal: Listening to Different Perspectives

- Legitimacy requires that, once accepted, patients and/or consumers be involved with equal credibility to other experts and participants. They should receive the same information and have the same opportunities to express their views.

- Publicity demands that health technology assessment (HTA) procedures—and their conclusions—be clearly understandable, accessible, and verifiable for the broadest possible audience.

- Relevance ensures that the information underlying the assessment must be sufficient to justify the conclusion reached.

- Appeal and revisability necessitate a mechanism that allows for the possibility of an appeal, whether based on new evidence or procedural concerns raised by any party.

- Responsibility entails adhering to the established rules. When patients and/or consumers are consulted appropriately, they should accept the final conclusion, even if it does not align with their preferences.

6. Capacity Building for Patients in HTA for Meaningful Involvement

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Houÿez, F. High Price Medicines and Health Budgets: The Role Patients’ and Consumers’ Organisations Can Play. Eur. J. Health Law 2020, 27, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nord, E.; Daniels, N.; Kamlet, M. QALYs: Some Challenges. Value Health 2009, 12, S10–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/somatropin (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Prader, A.; Labhart, A.; Willi, H. Ein syndrom von adipositas, kieinwuchs, kryptorchismus und oligophrenic nach myato-mieartigem zustand in neugeborenalte. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr 1956, 86, 1260–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Deal, C.L.; Tony, M.; Höybye, C.; Allen, D.B.; Tauber, M.; Christiansen, J.S. The 2011 Growth Hormone in Prader-Willi Syndrome Clinical Care Guidelines Workshop Participants. Growth Hormone Research Society workshop summary: Consensus guidelines for recombinant human growth hormone therapy in Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E1072-87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Le Bot, F.; Dard, O.; Didry, C.; Dupuy, C.; Perrin, C. L’homme-machine 2. Du travailleur augmenté à l’homme augmenté. In L’Homme et la Société 2018/2, n° 207; L’harmattan: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 9782343158730. [Google Scholar]

- Twenty years of treatment activism. Available online: https://www.eatg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/eatg-20-years-report.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fermaglich, L.J.; Miller, K.L. A comprehensive study of the rare diseases and conditions targeted by orphan drug designations and approvals over the forty years of the Orphan Drug Act. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eurordis Open Academy. Available online: https://openacademy.eurordis.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Bedlington, N.; Geissler, J.; Houyez, F.; Lightbourne, A.; Maskens, D.; Strammiello, V. Role of Patient Organisations. In Patient Involvement in Health Technology Assessment; Facey, K., Ploug Hansen, H., Single, A., Eds.; Adis: Singapore, 2017; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harousseau, J.; Pavlovic, M.; Mouas, H.; Meyer, F. Shaping European Early Dialogues: The Seed Project. Value Health 2015, 18, A562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roennow, A.; Sauvé, M.; Welling, J.; Riggs, R.J.; Kennedy, A.T.; Galetti, I.; Brown, E.; Leite, C.; Gonzalez, A.; Portales Guiraud, A.P.; et al. Collaboration between patient organisations and a clinical research sponsor in a rare disease condition: Learnings from a community advisory board and best practice for future collaborations. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfour-Lynn, I.M.; King, J.A. CFTR modulator therapies—Effect on life expectancy in people with cystic fibrosis. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2022, 42, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, M.; Jakab, I.; Mitkova, Z.; Kamusheva, M.; Tachkov, K.; Nemeth, B.; Zemplenyi, A.; Dawoud, D.; Delnoij, D.M.J.; Houÿez, F.; et al. Potential Barriers of Patient Involvement in Health Technology Assessment in Central and Eastern European Countries. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 922708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jakab, I.; Dimitrova, M.; Houÿez, F.; Bereczky, T.; Fövényes, M.; Maravic, Z.; Belina, I.; Andriciuc, C.; Tóth, K.; Piniazhko, O.; et al. Recommendations for patient involvement in health technology assessment in Central and Eastern European countries. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1176200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/evamed/CT-14927_ORKAMBI_PIC_INS_Avis3_CT14927.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Germeni, E.; Fifer, S.; Hiligsmann, M.; Stein, B.; Tonkinson, M.; Joshi, M.; Hanna, A.; Liden, B.; Marshall, D.A. A genuine need or nice to have? Understanding HTA representatives’ perspectives on the use of patient preference data. Int. J. Technol. Assess Health Care 2024, 40, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Janssens, R.; Barbier, L.; Muller, M.; Cleemput, I.; Stoeckert, I.; Whichello, C.; Levitan, B.; Hammad, T.A.; Girvalaki, C.; Ventura, J.J.; et al. How can patient preferences be used and communicated in the regulatory evaluation of medicinal products? Findings and recommendations from IMI PREFER and call to action. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1192770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beresniak, A.; Medina-Lara, A.; Auray, J.P.; De Wever, A.; Praet, J.C.; Tarricone, R.; Torbica, A.; Dupont, D.; Lamure, M.; Duru, G. Validation of the underlying assumptions of the quality-adjusted life-years outcome: Results from the ECHOUTCOME European project. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation (EU) 2021/2282 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2021 on health technology assessment and amending Directive 2011/24/EU. Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, 458, 1–32.

- EU4Health Programme (EU4H). Call for Proposals Under the Annual Work Programme 2022; European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA): Brussel, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- EUCAPA Website. Available online: https://www.eucapa.eu (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- EUPATI. HTA4Patients. Available online: https://eupati.eu/hta4patients/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- EURORDIS. EURORDIS Summer School. Available online: https://openacademy.eurordis.org/summer-school/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canada’s Drug Agency (CDA) Website. Available online: https://www.cadth.ca/patient-and-community-engagement (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Enhance HTA: An Enhanced Consumer Engagement Process in Australian Health Technology Assessment—A Report of Recommendations. 2024. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/enhance-hta-an-enhanced-consumer-engagement-process-in-australian-health-technology-assessment-a-report-of-recommendations (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- EMA’s Biennial Report on Stakeholder Engagement Activities 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/stakeholder-engagement-report-2022-2023_en.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- European Experts. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) Maintains a Public List of European Experts Who Provide Scientific Expertise to EMA’s Activities. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/how-we-work/european-medicines-regulatory-network/european-experts (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Market Access Society. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Houÿez, F.; Delaye, J. How Patients Can Contribute to the Assessments of Health Technologies. J. Mark. Access Health Policy 2025, 13, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmahp13040061

Houÿez F, Delaye J. How Patients Can Contribute to the Assessments of Health Technologies. Journal of Market Access & Health Policy. 2025; 13(4):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmahp13040061

Chicago/Turabian StyleHouÿez, François, and Julien Delaye. 2025. "How Patients Can Contribute to the Assessments of Health Technologies" Journal of Market Access & Health Policy 13, no. 4: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmahp13040061

APA StyleHouÿez, F., & Delaye, J. (2025). How Patients Can Contribute to the Assessments of Health Technologies. Journal of Market Access & Health Policy, 13(4), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmahp13040061