Geographic Ontologies, Gazetteers and Multilingualism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Geographic Ontologies

- “is a” (females and males are subtypes or subclasses of human being);

- “has a” (a paper has one or several authors);

- “part of” (a finger is a part of a hand).

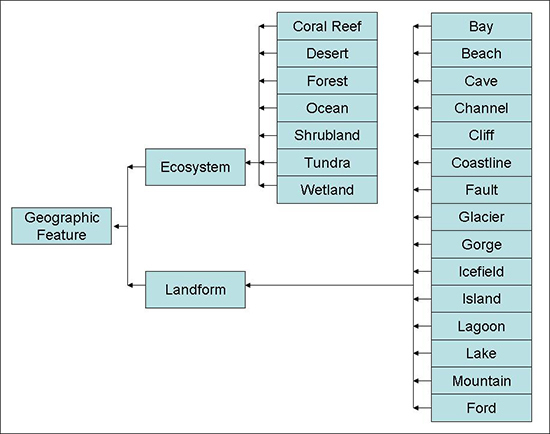

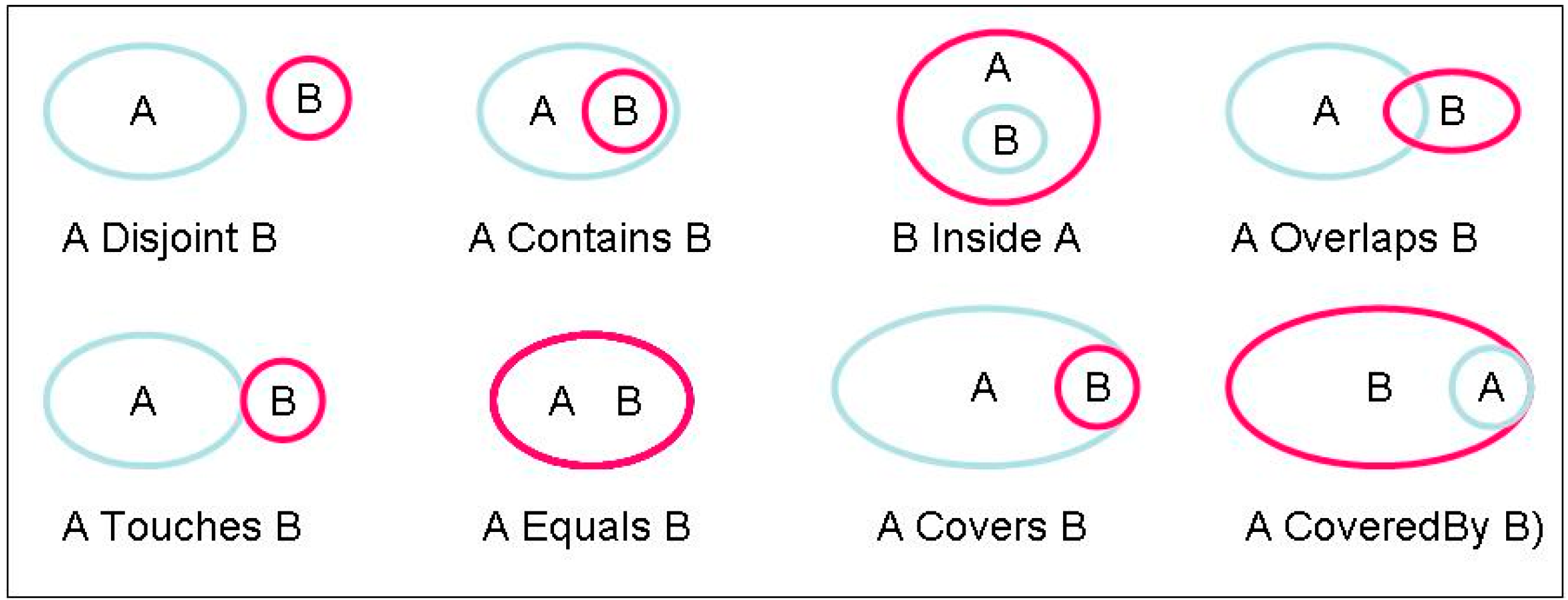

2.1. Geographic Features, Types and Languages

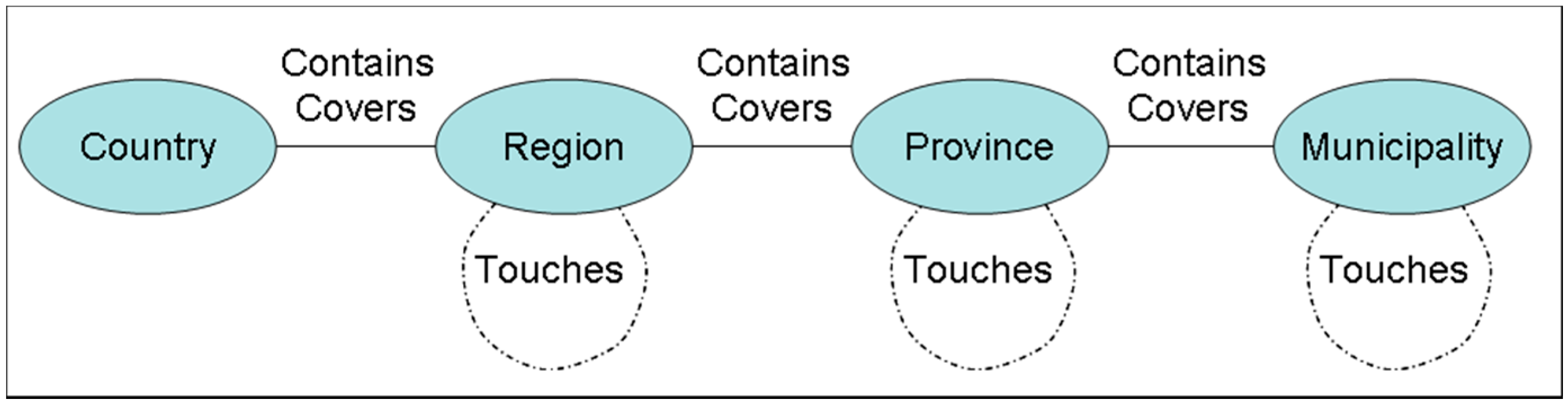

- Generally, they form an administrative tessellation (as defined by administrative laws of the concerned countries) and often a hierarchical tessellation (in which a zone of the first level can be decomposed into a second level tessellation (example: in the U.S., country, states, counties);

- However, this tessellation is often disrupted, because of the existence of external territories with special statuses; see, for instance, territories, such as Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands for the United States;

- Even if types are the same, they do not have the same meaning; compare, for instance, a Canadian province, such as “British Columbia”, and an Italian province (provincia in Italian) for which the size, statuses, prerogatives and governance are very different.

- the so-called administrative tessellations are often not strictly mathematical tessellations due to measurement errors and sliver polygons;

- and the spatial relationships could always be generalized or mutated due to scale effects (See [12] for more details); for instance, a road running along the seashore can have a “disjoint” relation or a “touches” relation according to the scale.

2.2. Ontological Categories and Languages

3. About Geographic Names and Gazetteers

3.1. What Is beneath a Name?

3.2. Generalities

- “Mississippi” can be the name of a river or of a state.

- The city, “Venice”, Italy, is also known as “Venezia”, “Venise”, “Venedig”, respectively, in Italian, French and German.

- The local name of the Greek city of “Athens” is “Αθήνα”; read [a’θina].

- “Istanbul” was known as “Byzantium” and “Constantinople” in the past.

- The modern city of Rome is much bigger than in Romulus’s time.

- There are two Georgias, one in the United States and another one in Caucasia.

- The toponym “Milano” can correspond to the city of Milano or the province of Milano.

- The river “Danube” crosses several European countries; practically in each country, it has a different name, “Donau” in Germany and Austria, “Dunaj” in Slovakia, “Duna” in Hungary, “Dunav” in Croatia and Serbia, “Dunav” and “Дунав” in Bulgaria, “Dunărea” in Romania and in Moldova and “Dunaj” and Дунай” in the Ukraine. It is also called “Danubio” in Italian and Spanish, “Tonava” in Finnish and “Δούναβης” in Greek. Moreover, its name is feminine in German and masculine in some other languages.

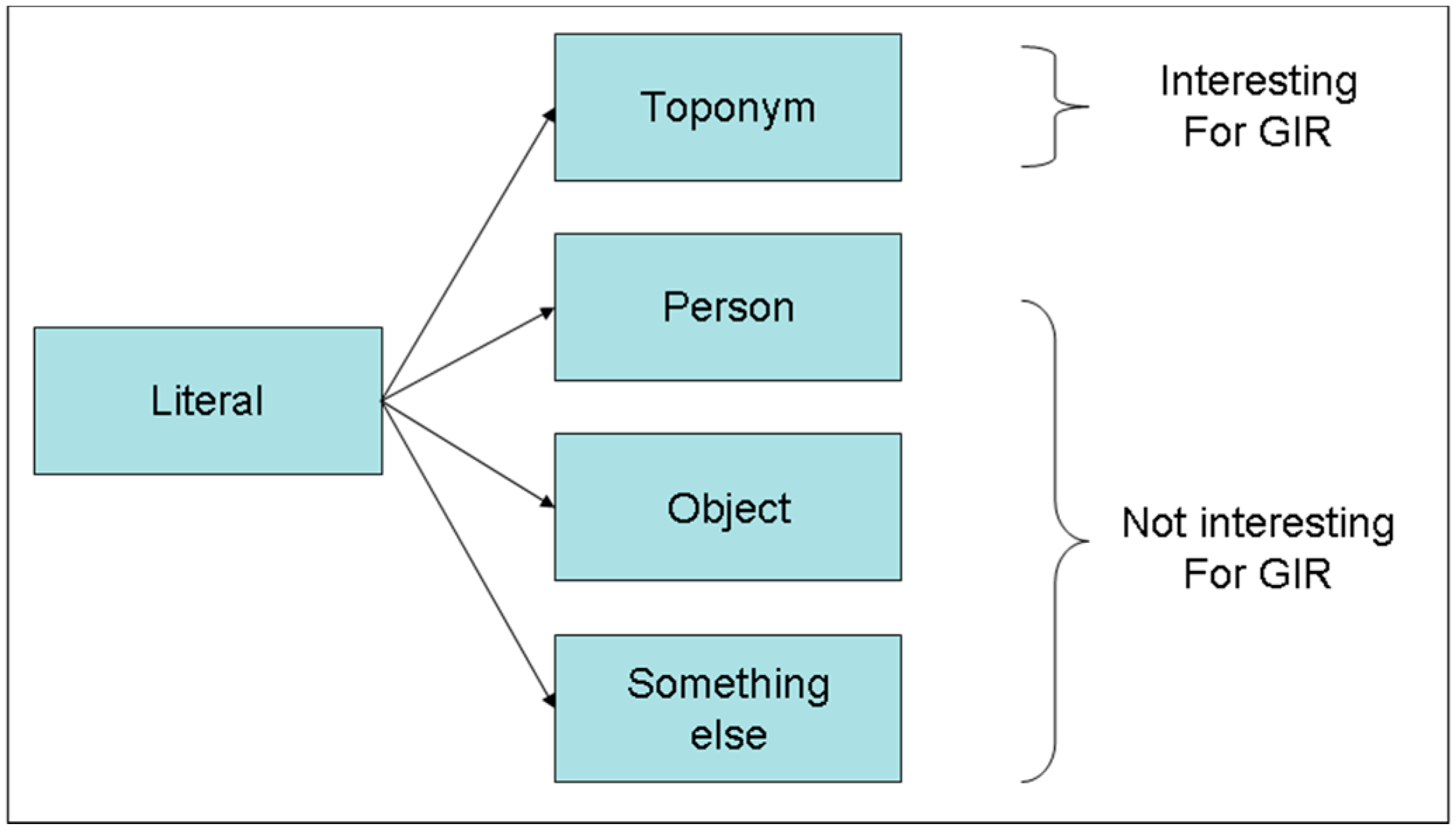

- Sometimes, names of places can be also names of something else; for instance “Washington” can also refer to George Washington or anybody with this first name or last name.

- In the U.K., there are several rivers named Avon.

- Some place names are formed of two or several words; for instance, “New Orleans”, “Los Angeles”, “Antigua and Barbuda”, “Trinidad and Tobago”, “Great Britain”, “Northern Ireland”, “Tierra del Fuego”, “El Puente de Alcántara”, etc.

- Some very long names can have simplifications; the well-known Welsh town “Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch” is often simplified to “Llanfair PG” or “Llanfairpwll”.

- Some abbreviations can be common, such as “L.A.” for “Los Angeles”, whereas its name at its inception was “El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles del Rio de la Porciúncula”;

- Peking became Beijing after a change of transcription to the Roman alphabet; but the capital of China has not modified its name in Chinese.

- In some languages, grammatical gender is important, so that place names can be feminine or masculine; for instance, in French, Italian and Spanish, names such as “Japan”, “Brazil” and “Portugal” are masculine, whereas “Argentina”, “Bolivia” and “Tunisia” are feminine.

- In addition, as the great majority of toponyms are singular, some can be plural, like “The Alps”; but for “The Netherlands”, the situation is more complex: plural in French (Les Pays-Bas), in Italian (I Paesi Bassi) and in Spanish (Los Países Bajos), whereas singular and plural are both acceptable in English (The Netherlands are, The Netherlands is);

- Some places have nicknames; e.g., Dixieland, Big Apple, City of the Lights, etc.

- Do not forget that in some languages, toponyms can have declensions, for instance for the Rhine River in German (der Rhein, des Rheins, etc.).

- a small country located in the Caribbean Islands;

- in Spain, a city capital of the eponymous province, a few other places located in Barcelona and Huelva provinces and a river in the Vizcaya province;

- in Colombia, three cities with this toponym;

- in the U.S., cities in California, Colorado, Kansas, Minnesota, Mississippi, etc.;

- in Mexico, a city in Yucatán;

- in Nicaragua, a city capital of the eponymous department;

- in Peru, a district.

- some streets comprise a few dozens of yards, whereas others several miles;

- in some human settlements, streets have no names;

- sometimes, there are variations about the way to write some street names; for instance “3rd Street”, “Third Street”, “Third St”; the words “avenues” and “boulevards” are commonly simplified into “Ave” and “Blvd” or “Bd”;

- in some countries, the equivalent of the words “street”, “avenue”, etc., are usually removed;

- in some places, streets can have several names; for instance, in New York City, “Sixth Avenue” is also known as “Avenue of the Americas”;

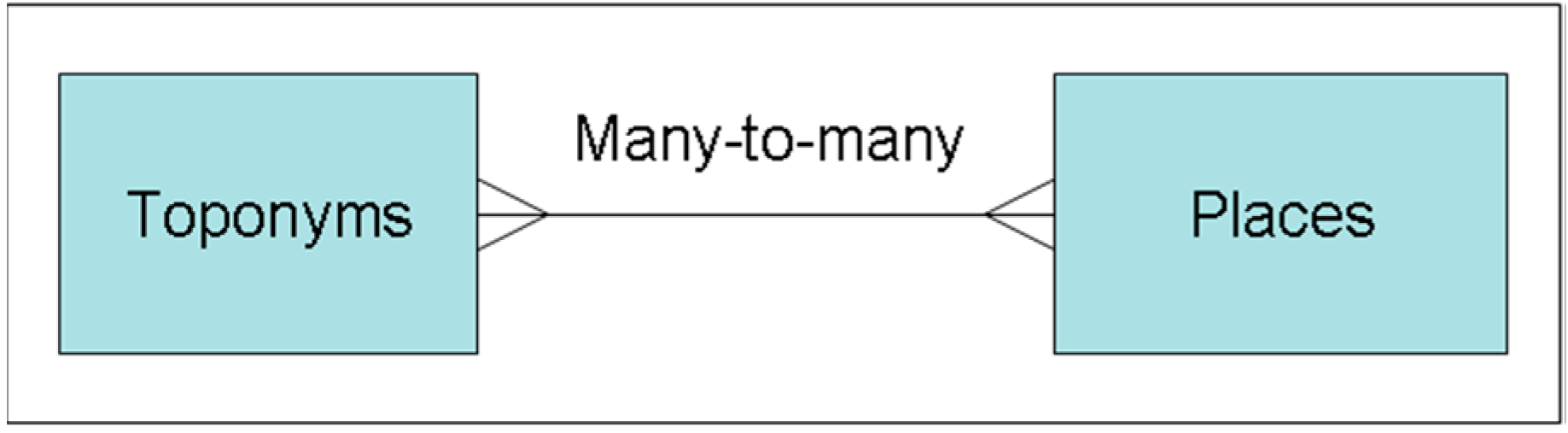

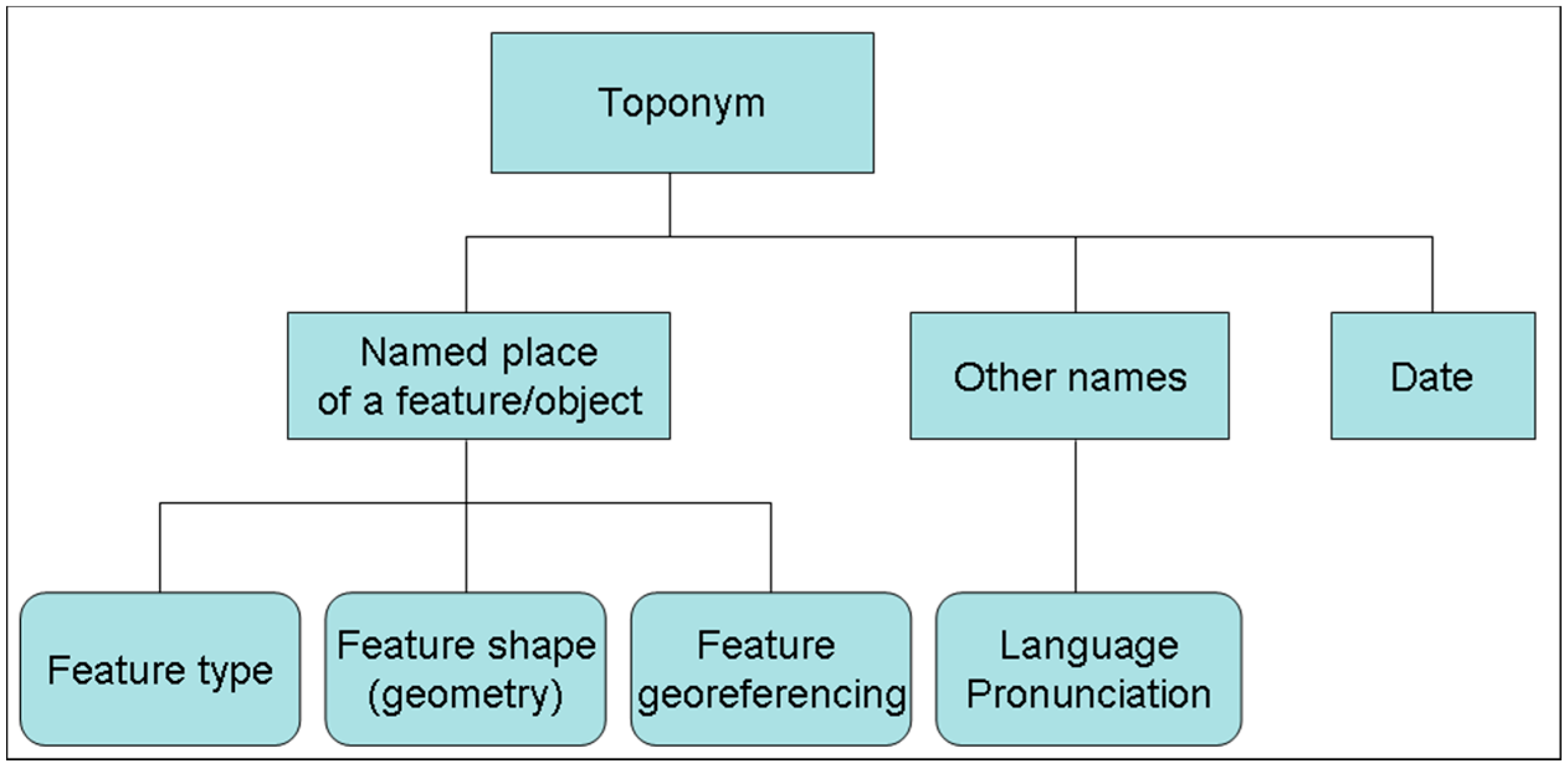

- toponym is the general name of a geographic feature;

- endonym is a local name in the official language of the country or in a well-established language occurring in that area where the feature is located; there may be several toponyms in countries with different official languages (Brussel in Flemish, Bruxelles in French);

- exonym is a name in languages other than the official languages; for instance Brussels in English;

- archeonym is a name that existed in the past: for instance, Byzantium for Istanbul;

- hyperonym and hyponym are the names of places with a hierarchy; hyponym is the opposite of hyperonym; for instance, Europe is a hyperonym of France, whereas France is a hyponym of Europe;

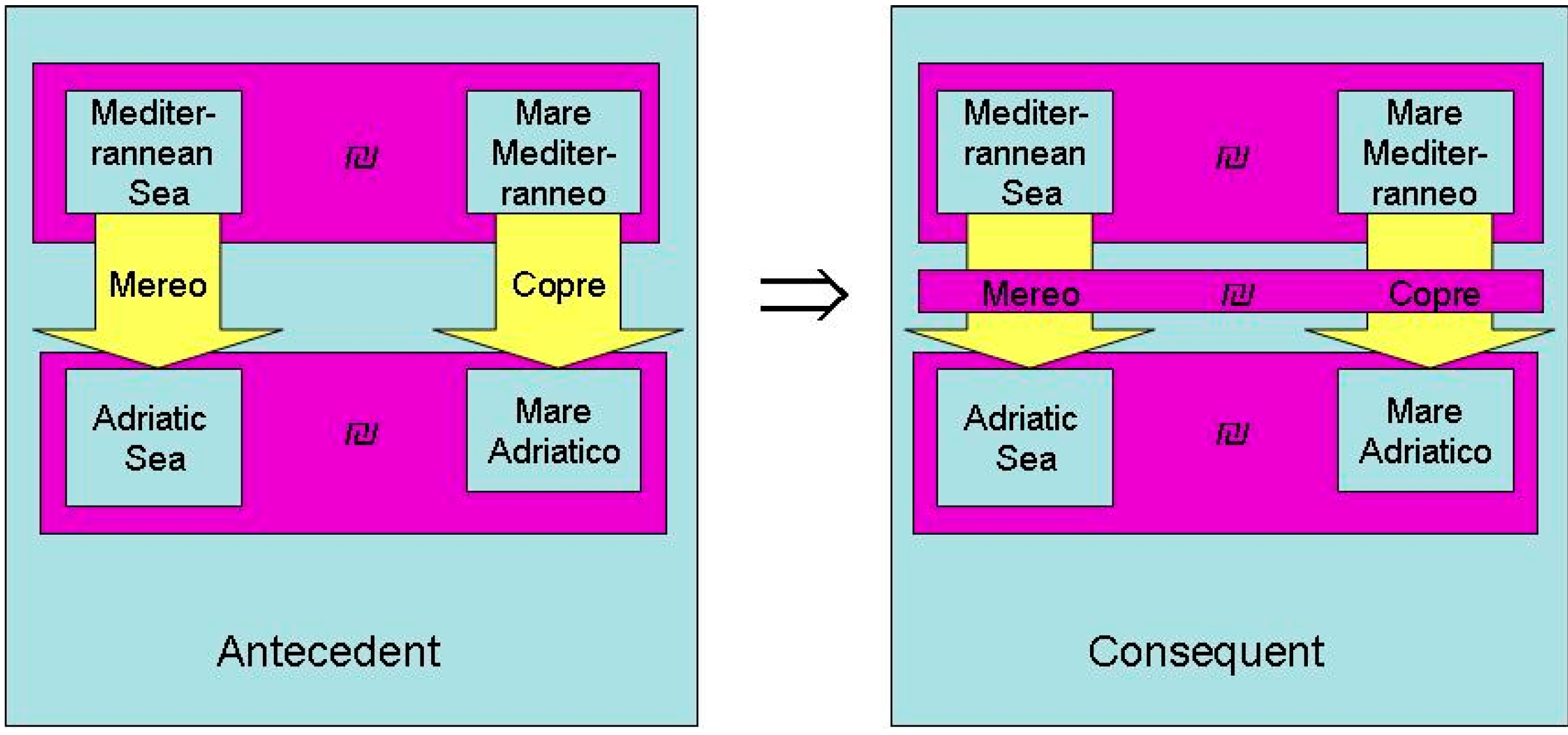

- meronym is a name of a part of a place without a hierarchy; sometimes the expression partonym is used; for instance “Adriatic Sea” is a meronym of the Mediterranean Sea;

- hydronym is a name of a waterbody;

- oronym is a name for a hill or a mountain;

3.3. Examples

3.3.1. Simple Gazetteer

- Placenames (ID, toponym);

- Equivalence (ID1, ID2).

3.3.2. Gazetteer as an Index for a Map (Street Directory)

- Location1 (street-name, CWbeginning-location, CWending-location)

- Location2 (street-name, beginning-street-name, ending-street-name)

3.3.3. Gazetteer for a Local Post-Office

- Urban-feature (name, street-address)

3.3.4. Gazetteer for Hydrology

- Hydronym (id, onto-type, geometry)

- Endonym (id, hydronym)

- Exonym (id, language, hydronym)

- Tributary (id1, id2, location)

- Estuary (id1, id2, location)

- Meronym (id1, id2).

3.3.5. Gazetteer for the History of a Place

- Placename (id, onto-type, geometry, beginning-date)

- Archeonym (id, language, toponym, geometry, beginning-date, ending-date)

- Exonym (id, language, toponym).

3.3.6. Gazetteer Covering Several Actual Countries, for Instance Europe

- Placename (id, onto-type, geometry, beginning-date)

- Exonym (id, language, toponym)

- Hydronym (id, onto-type, geometry)

- Endonym (id, hydronym)

- Exonym (id, language, hydronym)

- Meronym (id1, id2).

3.4. Existing Systems

3.4.1. GeoNames

- Children, i.e., the list of administrative divisions (first relative sublevel);

- Hierarchy, i.e., the list of toponyms higher up in the hierarchy of a place name;

- Neighbors, i.e., the list of all neighbors for a country or administrative division;

- Contains, i.e., the list of all features within the feature;

- Siblings, i.e., the list of all siblings of a toponym at the same level.

- <geoname>

- <toponymName>Sicilia</toponymName>

- <name>Sicily</name>

- <lat>37.75</lat><lng>14.25</lng>

- <geonameId>2523119</geonameId>

- <countryCode>IT</countryCode>

- <countryName>Italy</countryName>

- <numberOfChildren>9</numberOfChildren>

- </geoname>

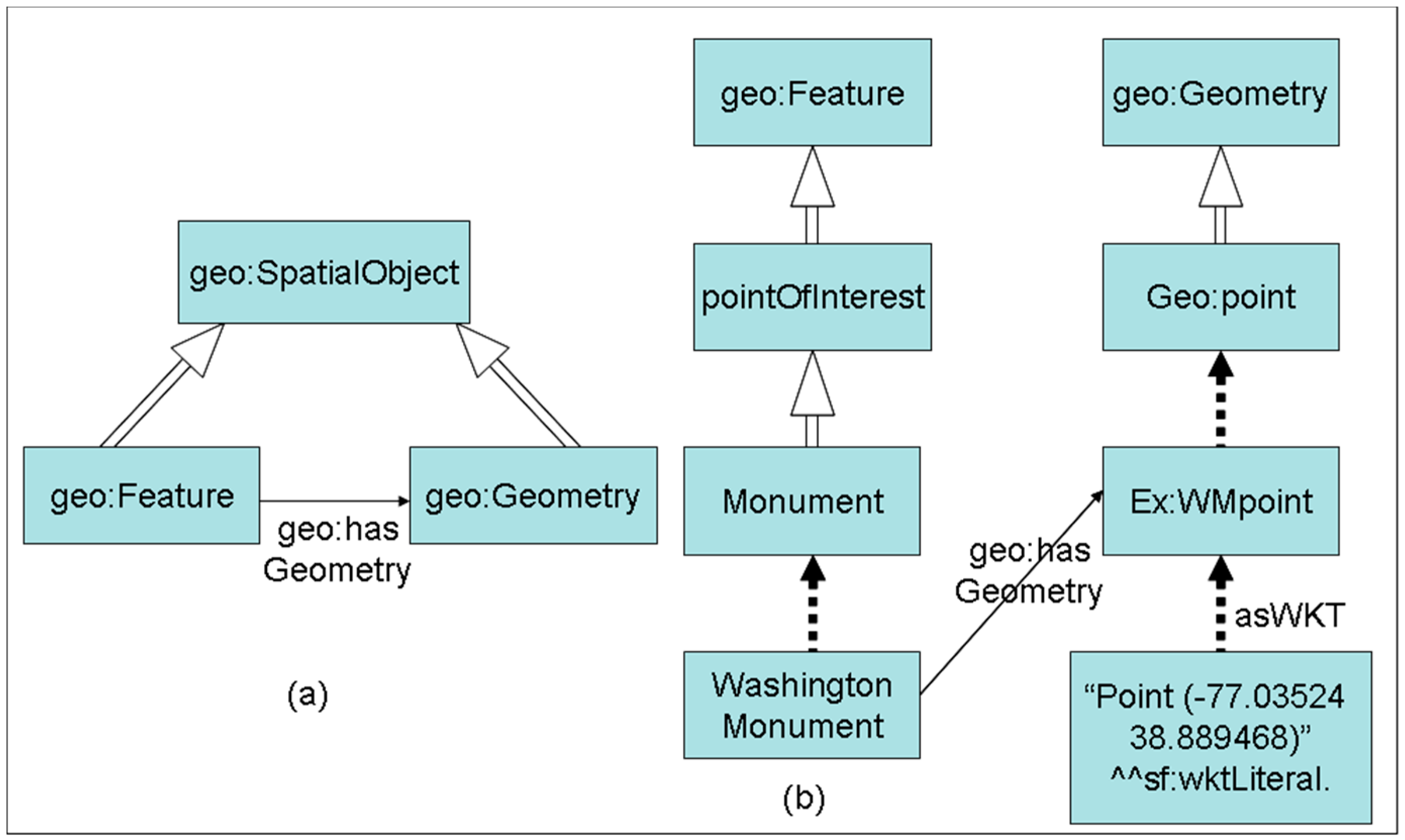

3.4.2. GeoSPARQL

- PREFIX abc: <http://example.com/exampleOntology#>

- SELECT ?capital ?country

- WHERE {

- ?x abc:cityname ?capital ;

- abc:isCapitalOf ?y .

- ?y abc:countryname ?country ;

- abc:isInContinent abc:Africa.

- }

- PREFIX geo: <http://www.opengis.net/ont/geosparql#>

- PREFIX geof: <http://www.opengis.net/def/function/geosparql/>

- PREFIX sf: <http://www.opengis.net/ont/sf#>

- PREFIX ex: <http://example.org/PointOfInterest#>

- SELECT ?a

- WHERE {

- ?a geo:hasGeometry

- ?ageo .

- ?ageo geo:asWKT

- ?alit

- FILTER( geof:sfWithin(?alit, “Polygon((-77.089005 38.913574,-77.029953 38.913574,-77.029953 38.886321,-77.089005 38.886321,-77.089005 38.913574))”^^sf:wktLiteral)) }

- PREFIX co: <http://www.geonames.org/countries/#>

- PREFIX xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#>

- PREFIX geo: <http://www.w3.org/2003/01/geo/wgs84_pos#>

- SELECT ?link ?name ?lat ?lon

- WHERE {

- ?link gs:within(51.139725 -0.895386 51.833232 0.645447) .

- ?link gn:name ?name .

- ?link gn:featureCode gn:S.AIRP .

- ?link geo:lat ?lat .

- ?link geo:long ?lon }

- SELECT ?parcel ?hwy

- WHERE { ?parcel rdf:type :Commercial .

- ?parcel rdf:type ogc:GeometryObject .

- ?hwy rdf:type :Arterial_Street .

- ?hwy rdf:type ogc:GeometryObject .

- ?parcel ogc:touches ?hwy }

4. Inference Rules for Matching Geographic Ontologies in Different Languages

4.1. Conceptual Framework

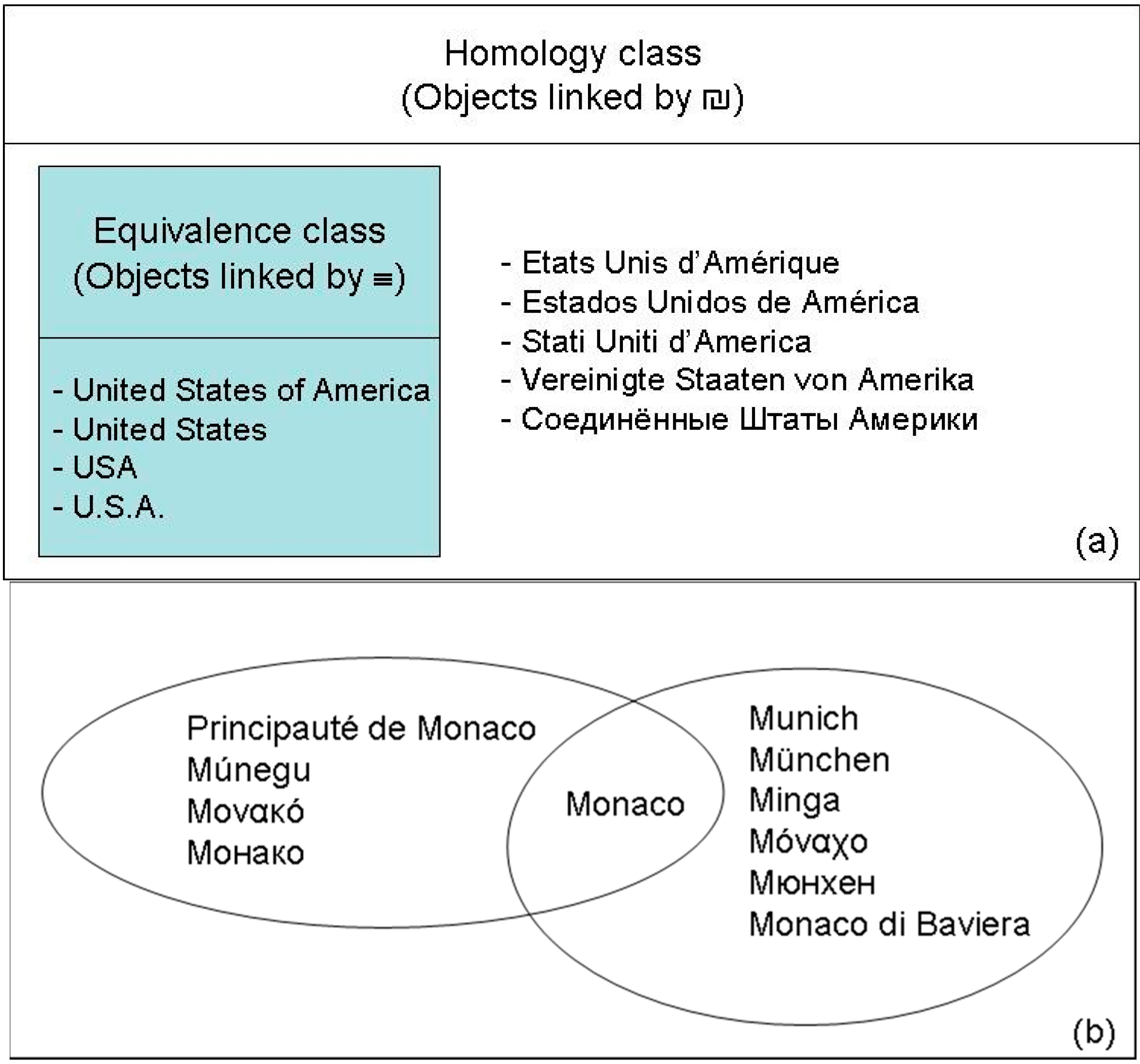

4.1.1. Homology Relations

4.1.2. Geographic Objects

- GeoID corresponds to the object identifier; this identifier is only used internally and will generally not be known by users;

- Geom corresponds to the geometry of the objects;

- Toponym corresponds to the name of the geographic object in the concerned language; in addition, this will be the main user’s identifier as listed in a monolingual gazetteer;

- Type corresponds to the type of this object as defined in an ontology.

4.1.3. Relations

4.1.4. Geometry

4.1.5. Languages

4.1.6. Toponyms and Located Toponyms

- ENG.Earth ⊃ “Pacific Ocean”

- ENG. Earth ⊃ America ⊃ “North America” ⊃ California ⊃ Granada

- ENG.Earth ⊃ America ⊃ “North America” ⊃ “Lake Erie”.

- country inclusion: ENG.Earth ⊃ “U.S.A.” ⊃ Hawaii;

- location inclusion: ENG.Earth ⊃ “Pacific Ocean” ⊃ Hawaii.

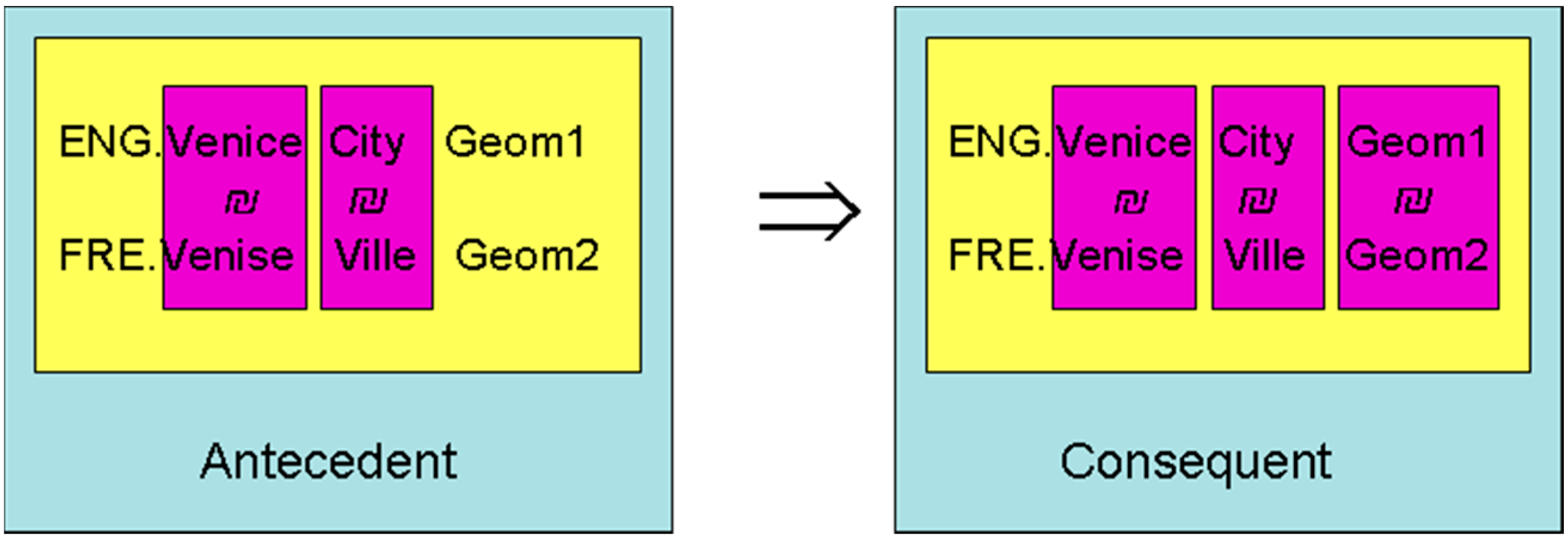

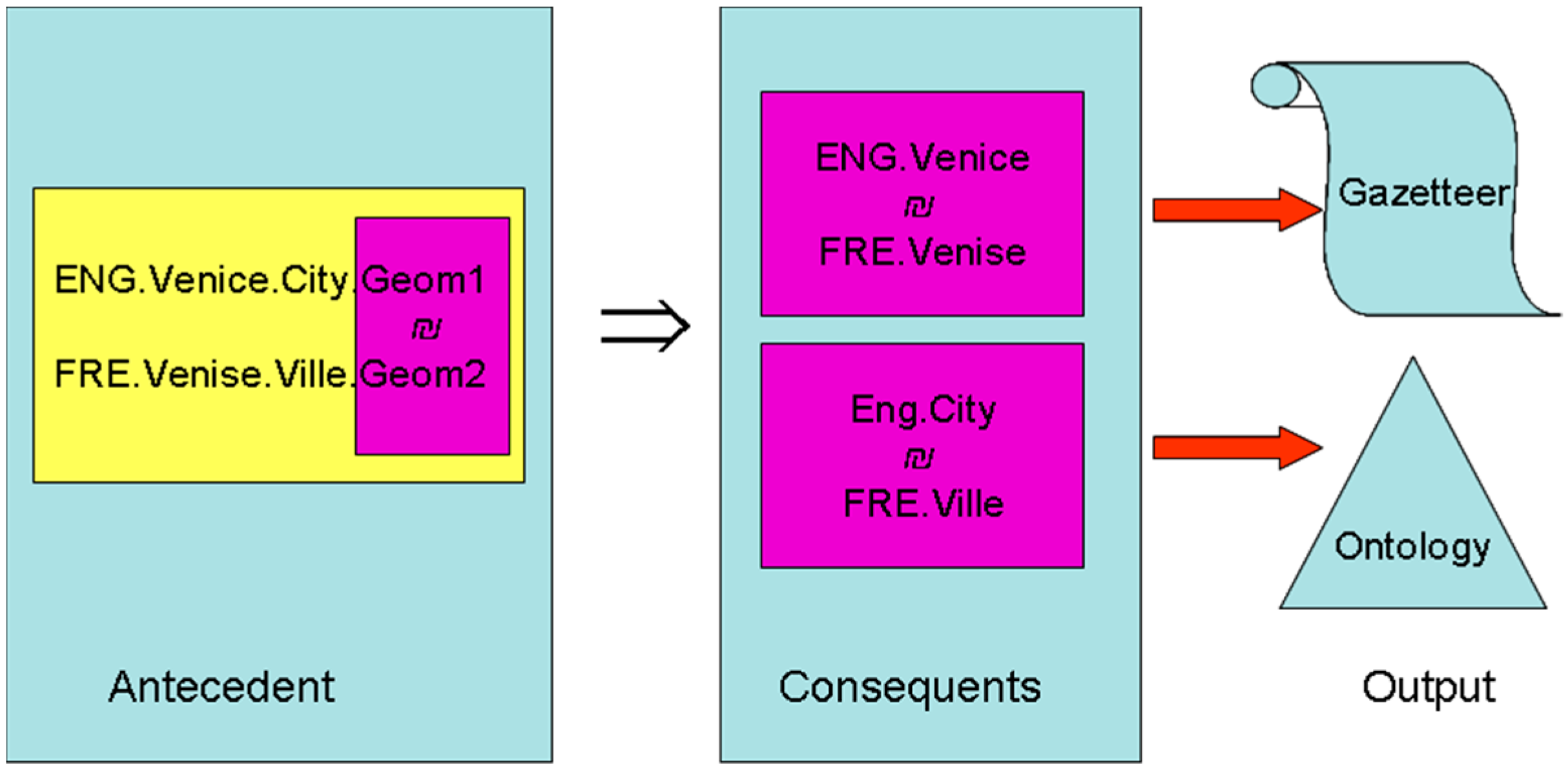

4.1.7. Matching Two Geographic Ontologies in Different Languages

- types will be linked by homology relations;

- and ontological relations will also be linked via homology relations.

4.1.8. Homologous Geographic Objects

- adopt the more recent geographic description

- adopt the more accurate

- or create a mix of both.

4.1.9. Geographic Knowledge Base

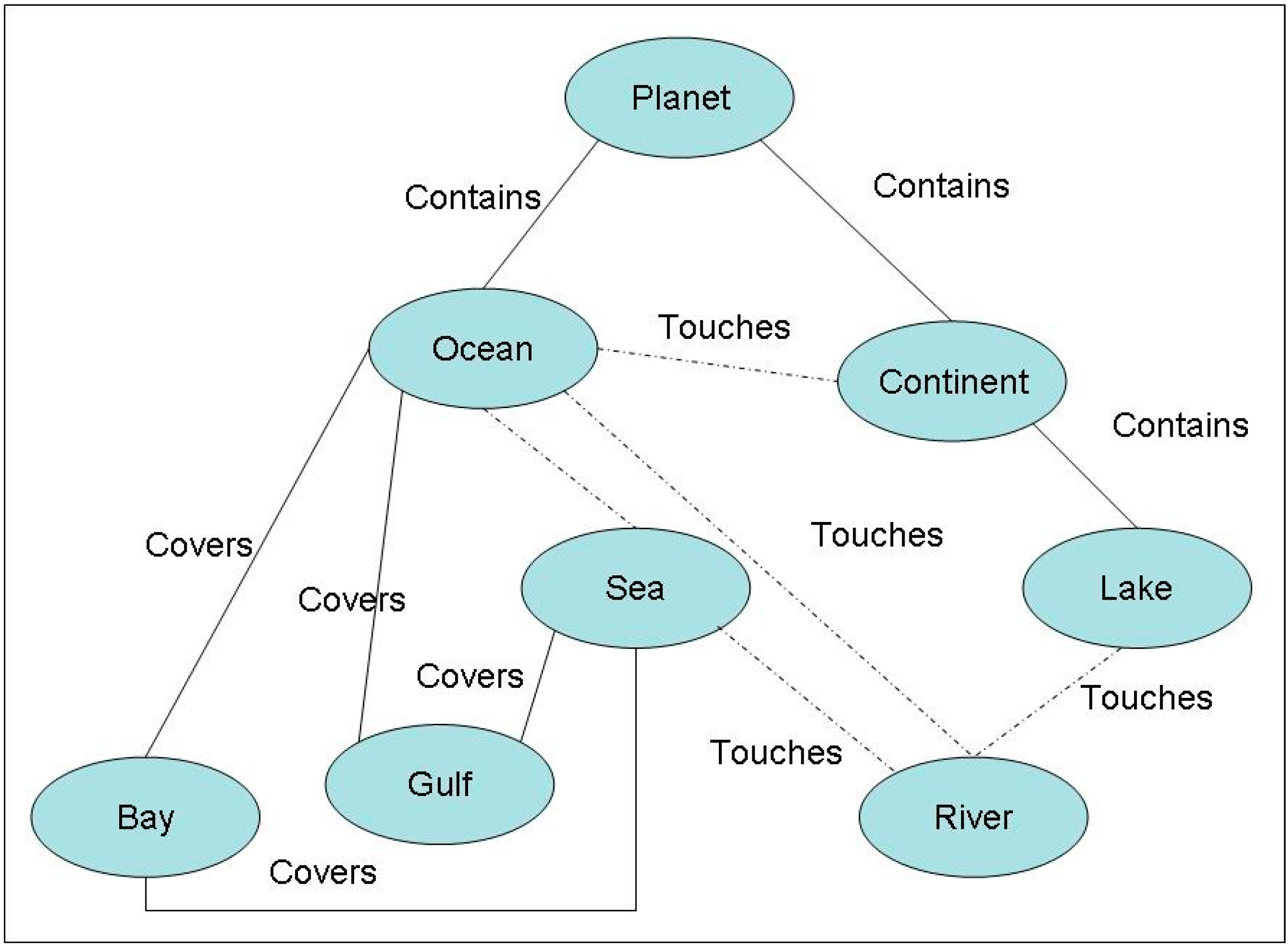

- the three classical ontological relations, is_a, i.e., the “is-a” relation, has_a, i.e., the “has-a” relation and part_of, i.e., the “part-of” relation;

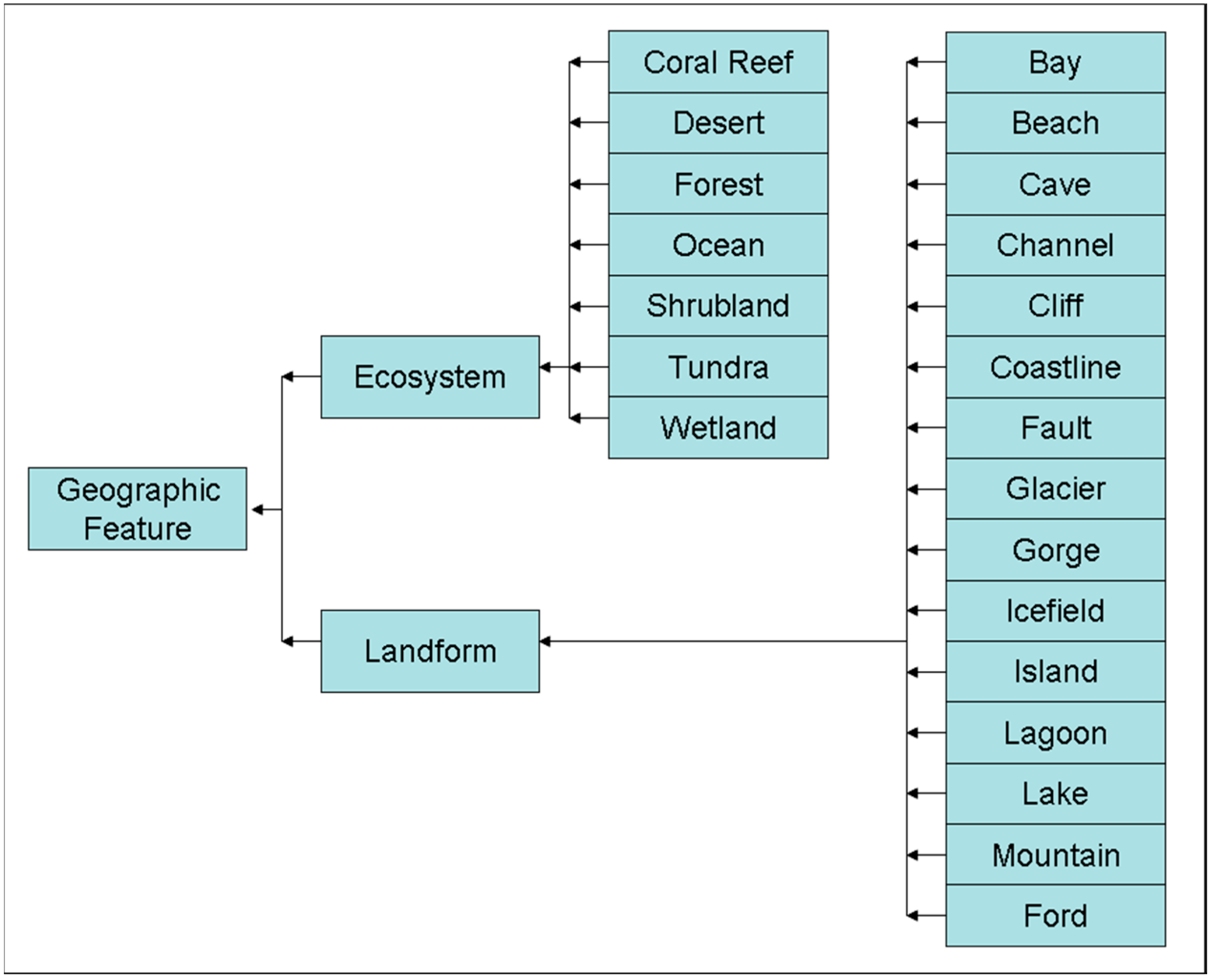

- the eight Egenhofer topological relations (see Figure 2) are, respectively, Disjoint, Contains, Inside, Overlaps, Touches, Equals, Covers and CoveredBy;

- and possibly other additional relations.

4.2. Geographic Rules

4.2.1. Inferring Geometry

∧(Og1. λ1.Toponym1 ₪ Og2. λ2.Toponym2)

∧(Og1. λ1.Type1 ₪ Og2. λ2.Type2)

∧(Og2.Geom2 = null)

⇒

(Og1 ₪ Og2)

∧(Og1. λ1.Toponym1 ₪ Og2. λ2.Toponym2)

∧(Og1. λ1.Type1 ₪ Og2. λ2.Type2)

∧(Og1.Geom1 INSIDE (MBR)

∧(Og2.Geom2 = null)

⇒

(Og1 ₪ Og2)

4.2.2. From Homologous Geometry to Homologous Objects

- -

- their toponyms are homologous;

- -

- their types are homologous;

- -

- and so, the geographic objects are homologous.

⇒(Og1.Toponym1 ₪ Og2.Toponym2)

∨(Og1.Type1 ₪ Og2Type2)

∨(Og1 ₪ Og2)

4.2.3. Inferring Ontological Relations

(Og11 ₪ Og21) ∧ (Og12 ₪ Og22)

(Og11 R1 Og12) ∧ (Og21 R2 Og22)

⇒(R1 ₪ R2)

- to confer the same name, but in this case, it is not correct in the second language;

- or to ask an expert to propose a solution for the translation of this name.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laurini, R. Spatial multidabase topological continuity and indexing: A step towards seamless GIS data interoperability. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1998, 12, 373–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.R. A translation approach to portable ontologies. Knowl. Acquis. 1993, 5, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F.; Hill, L.L. Introduction to digital gazetteer research. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2008, 22, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Mark, D. Do mountains exist? Towards an ontology of landforms. Environ. Plan. B 2003, 30, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.B.; Abdelmoty, A.I.; Fu, G. Maintaining Ontologies for Geographical Information Retrieval on the Web. In Proceedings of the OTM Confederated International Conference, CoopIS, DOA, and ODBASE 2003, Catania, Italy, 3–7 November 2003; Meersam, R., Tari, Z., Schmidt, D.C., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; Volume 2888, pp. 934–951. [Google Scholar]

- Laurini, R. Importance of spatial relationships for geographic ontologies. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Informatics and Urban and Regional Planning INPUT 2012, Cagliari, Italy, 10–12 May 2012; pp. 122–134.

- Kavouras, M.; Kokla, M.; Tomai, E. Comparing categories among geographic ontologies. Comput. Geosci. 2005, 31, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurini, R. Pre-consensus Ontologies and Urban Databases. In Ontologies for Urban Development. Studies in Computational Intelligence; Teller, J., Lee, J.R., Roussey, C., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 61, pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Egenhofer, M.; Franzosa, R.D. Point-set topological spatial relations. Int. J. GIS 1991, 5, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Egenhofer, M. Deriving the composition of binary topological relations. J. Vis. Lang. Comput. 1994, 5, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randell, D.A.; Zhan, C.; Cohn, A.G. A Spatial Logic based on Regions and Connection. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Knowledge Representation and Reasoning, Cambridge, MA, USA, 26–29 October 1992; pp. 165–176.

- Laurini, R. A conceptual framework for geographic knowledge engineering. J. Vis. Lang. Comput. 2014, 25, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, J.; Keita, A.-K.; Roussey, C.; Laurini, R. Urban Ontologies for an improved communication in urban civil engineering projects. Cybergeo. Eur. J. Geogr. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euzenat, J.; Shvaiko, P. Ontology Matching; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, N. Formal Ontology and Information Systems. In Formal Ontology in Information Systems; Guarino, N., Ed.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, B.; Brennan, R.; O’Sullivanm, D. A configurable translation-based cross-lingual ontology mapping system to adjust mapping outcomes. J. Web Semant. 2012, 15, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keßler, C.; Janowicz, K.; Bishr, M. An Agenda for the Next Generation Gazetteer: Geographic Information Contribution and Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, New York, NY, USA, 4–6 November 2009; pp. 91–100, ISBN:978–C1-60558-649-6.

- Hećimović, Z.; Ciceli, T. Spatial Intelligence and Toponyms. In Proceedings of the 26th International Cartographic Conference, Dresden, Germany, 25–30 August 2013. ISBN:978-1-907075-06-3.

- URISA. Available online: http://www.urisa.org (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- Jakir, Ž.; Hećimović, Ž.; Štefan, Z. Place Names Ontologies. In Advances in Cartography. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Ruas, A., Ed.; Springer Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 331–349. [Google Scholar]

- IATA. Available online: http://www.iata.org (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- GEONAMES. Available online: http://www.geonames.org (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- GeoSPARQL. Available online: http://geosparql.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- OGC. Available online: http://www.opengeospatial.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- SPARQL. Available online: http://www.w3.org/2009/sparql/wiki/Main_Page (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- RDF. Available online: http://www.w3.org/RDF/ (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- Laurini, R.; Thompson, D. Fundamentals of Spatial Information Systems; A.P.I.C. Series, No 37; Academic Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Language Codes. Available online: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/language_codes.htm (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- Egenhofer, M. Spherical topological relations. J. Data Semant. 2005, 3, 25–49. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laurini, R. Geographic Ontologies, Gazetteers and Multilingualism. Future Internet 2015, 7, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi7010001

Laurini R. Geographic Ontologies, Gazetteers and Multilingualism. Future Internet. 2015; 7(1):1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi7010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaurini, Robert. 2015. "Geographic Ontologies, Gazetteers and Multilingualism" Future Internet 7, no. 1: 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi7010001

APA StyleLaurini, R. (2015). Geographic Ontologies, Gazetteers and Multilingualism. Future Internet, 7(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi7010001