A Dual-Attention CNN–GCN–BiLSTM Framework for Intelligent Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- It integrates multi-scale CNN, attention fusion, GCN, and BiLSTM to capture comprehensive spatio-temporal dynamics of WSN traffic.

- 2.

- The model learns hierarchical and context-aware embeddings that improve separability between normal and anomalous traffic. This is attained through multi-branch feature extraction and adaptive attention weighting.

- 3.

- It introduces advanced preprocessing and normalization steps to ensure stability.

2. Related Works

- Deployment Realism: Existing models overlook computational and energy limitations of distributed sensor nodes.

- Temporal–Spatial Dependency: Most IDSs fail to jointly model both the temporal evolution of attacks and spatial correlations among nodes.

- Dynamic Adaptation: Static training prevents adaptation to changing traffic distributions and novel intrusions.

- Interpretability and Fusion: Few works integrate multi-level feature fusion or interpretable decision mechanisms within hybrid deep architectures.

3. Materials and Methods

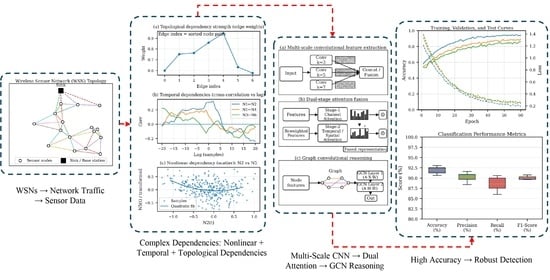

3.1. Design Framework

| Algorithm 1 Proposed Intrusion Detection Framework. |

|

3.2. Dataset Description

3.3. Data Preprocessing

3.4. Feature Engineering

3.5. Model Design

3.5.1. Multi-Scale Convolutional Block

3.5.2. Dual-Stage Attention Fusion

3.5.3. Graph Convolutional Regularization

3.5.4. Bidirectional LSTM with Contextual Attention

3.5.5. Hierarchical Aggregation and Output Projection

3.6. Evaluation and Simulation

4. Results

4.1. Training and Validation Performance

4.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

4.3. Model Interpretability and Structural Visualization

4.4. Learning Dynamics and Validation Logs

4.5. Comparative Evaluation

4.6. Discussion

4.7. Practical Implications, Achieved Goals, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Puccinelli, D.; Haenggi, M. Wireless sensor networks: Applications and challenges of ubiquitous sensing. IEEE Circuits Syst. Mag. 2005, 5, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, L.M.; Velez, F.J.; Lebres, A.S. Survey on the Characterization and Classification of Wireless Sensor Network Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 1860–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunterngchit, C.; Pornchaivivat, S.; Bunterngchit, Y. Productivity Improvement by Retrofit Concept in Auto Parts Factories. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Conference on Industrial Technology and Management (ICITM), Cambridge, UK, 2–4 March 2019; pp. 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.F.; Shazali, K. Wireless Sensor Network Applications: A Study in Environment Monitoring System. Procedia Eng. 2012, 41, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunterngchit, C.; Baniata, L.H.; Baniata, M.H.; ALDabbas, A.; Khair, M.A.; Chearanai, T.; Kang, S. GACL-Net: Hybrid Deep Learning Framework for Accurate Motor Imagery Classification in Stroke Rehabilitation. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 83, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhaya, L.; Sharma, P.; Bhagwatikar, G.; Kumar, A. Wireless Sensor Network Based Smart Grid Communications: Cyber Attacks, Intrusion Detection System and Topology Control. Electronics 2017, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodanović, R.; Rančić, D.; Vulić, I.; Zorić, N.; Bogićević, D.; Ostojić, G.; Sarang, S.; Stankovski, S. Wireless Sensor Network in Agriculture: Model of Cyber Security. Sensors 2020, 20, 6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. A Survey on Cybersecurity in IoT. Future Internet 2025, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M.; Habib, S.; Javed, A.R.; Rizwan, M.; Srivastava, G.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Lin, J.C.W. Applications of wireless sensor networks and internet of things frameworks in the industry revolution 4.0: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyeres, M.; Kenyeres, J.; Hassankhani Dolatabadi, S. Distributed consensus gossip-based data fusion for suppressing incorrect sensor readings in wireless sensor networks. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2025, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, N.; Liu, Z.; KC, D.B.; Gokaraju, B.; Roy, K. Comparison of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models for Network Intrusion Detection Systems. Future Internet 2020, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, E.; Cloete, E.; Venter, L. A comparison of Intrusion Detection systems. Comput. Secur. 2001, 20, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulganiyu, O.H.; Ait Tchakoucht, T.; Saheed, Y.K. A systematic literature review for network intrusion detection system (IDS). Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 22, 1125–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, A.; Alaryani, M.; Kaddoura, S. A comparative study of machine learning and deep learning models in binary and multiclass classification for intrusion detection systems. Array 2025, 26, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbouni, A.; Gunawan, T.S.; Habaebi, M.H.; Halbouni, M.; Kartiwi, M.; Ahmad, R. CNN-LSTM: Hybrid Deep Neural Network for Network Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99837–99849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayakumar, R.; Alazab, M.; Soman, K.P.; Poornachandran, P.; Al-Nemrat, A.; Venkatraman, S. Deep Learning Approach for Intelligent Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41525–41550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, H.; Faheem, M.; Bashir Ahmad, M. Machine Learning Techniques for Enhanced Intrusion Detection in IoT Security. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 31140–31158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A. Novel Approach for Intrusion Detection Attacks on Small Drones Using ConvLSTM Model. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 149238–149253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in cybersecurity: A deep dive into state-of-the-art techniques and future paradigms. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 6969–7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisat, A.; Alazab, A. A critical review of intrusion detection systems in the internet of things: Techniques, deployment strategy, validation strategy, attacks, public datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity 2021, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houda, Z.A.E.; Naboulsi, D.; Kaddoum, G. A Privacy-Preserving Collaborative Jamming Attacks Detection Framework Using Federated Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 12153–12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyakumar, S.R.; Rahman, M.Z.U.; Sinha, D.K.; Kumar, P.R.; Vimal, V.; Singh, K.U.; Syamsundararao, T.; Kumar, J.N.V.R.S.; Balajee, J. An Innovative Secure and Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning-Based Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Intrusion Detection in Internet-Enabled Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zou, H.; Zhou, P.; Shen, Y.; Li, D.; Li, W. CBCTL-IDS: A Transfer Learning-Based Intrusion Detection System Optimized With the Black Kite Algorithm for IoT-Enabled Smart Agriculture. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 46601–46615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birahim, S.A.; Paul, A.; Rahman, F.; Islam, Y.; Roy, T.; Asif Hasan, M.; Haque, F.; Chowdhury, M.E.H. Intrusion Detection for Wireless Sensor Network Using Particle Swarm Optimization Based Explainable Ensemble Machine Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13711–13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, F.F.; Asiri, M.M.; Alrayes, F.S.; Aljameel, S.S.; Salama, A.S.; Hilal, A.M. Red Kite Optimization Algorithm with Average Ensemble Model for Intrusion Detection for Secure IoT. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 131749–131758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atitallah, S.B.; Driss, M.; Boulila, W.; Koubaa, A. Securing Industrial IoT Environments: A Fuzzy Graph Attention Network for Robust Intrusion Detection. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Gu, H.; Xie, L.; Yang, H.; Na, Z. ST-IAOA-XGBoost: An Efficient Data-Balanced Intrusion Detection Method for WSN. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 1768–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.M.; Marouane, H.; Fakhfakh, A. Stochastic Gradient Descent Intrusions Detection for Wireless Sensor Network Attack Detection System Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 3825–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, I.; Al-Kasasbeh, B.; AL-Akhras, M. WSN-DS: A Dataset for Intrusion Detection Systems in Wireless Sensor Networks. J. Sens. 2016, 2016, 4731953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriwala, N.; Rathee, P. An approach to increase the wireless sensor network lifetime. In Proceedings of the 2012 World Congress on Information and Communication Technologies, Trivandrum, India, 30 October–2 November 2012; pp. 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Methodology/Model | Dataset | Key Limitation/Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | Federated learning with secure aggregation for jamming attack detection | WSN-DS (jamming classes) | Limited to jamming attacks; lacks multi-attack scalability |

| [22] | Hybrid SCNN–BiLSTM optimized via African vulture optimization under a federated learning setup | WSN-DS, CIC-IDS2017 | Low communication efficiency in FL; lacks interpretability |

| [23] | Transfer learning with MobileNet/VGG19 ensemble optimized by Black Kite Algorithm | ToN-IoT, Edge-IIoTset, WSN-DS | High computational load; poor real-time adaptability |

| [15] | CNN–LSTM hybrid model integrating spatial–temporal dependencies | WSN-DS (binary and multi-class) | Class imbalance and explainability not addressed |

| [16] | DL benchmarked against classical ML baselines | KDDCup’99, NSL-KDD, WSN-DS | No WSN-specific topology modeling; high false positives |

| [24] | PSO-based feature selection with RF, DT, and kNN ensemble plus LIME/SHAP explanations | WSN-DS (Binary) | No temporal or spatial dependency modeling |

| [17] | SMOTE-based balancing and PCC feature selection for ML/DL comparison | WSN-DS, UNSW-NB15, CIC-IDS2017 | No topology-aware or energy-efficient design |

| [18] | ConvLSTM for spatial–temporal intrusion detection in IoD networks | WSN-DS, NSL-KDD, Drone dataset | Limited to UAVs context; weak transferability to WSNs |

| [25] | Red Kite Optimization with average ensemble fusion and LCWOA tuning | WSN-DS (Binary) | No adaptive temporal modeling; lacks robustness to evolving threats |

| [26] | Fuzzy graph attention network for relational uncertainty learning | Edge-IIoTSet, CIC-Malmem, WSN-DS | Computationally expensive; unsuitable for constrained WSNs |

| [28] | SGD-based optimization for lightweight ML classifiers in WSN intrusion detection | WSN-DS (Binary) | Simplistic linear models; limited scalability for dense WSNs |

| [27] | Improved arithmetic optimization algorithm integrated with XGBoost | WSN-DS (Binary) | Static learning; lacks adaptive or online retraining |

| Feature Symbol | Description | Feature Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| id | A unique identifier assigned to each sensor node; distinguishes nodes across rounds and stages. | Time | Current simulation time of the node representing its temporal position in the network. |

| Is_CH | Binary flag indicating whether a node is a cluster head (1) or a normal node (0). | who_CH | Identifier of the cluster head associated with the node in the current round. |

| Dist_To_CH | Distance between the node and its respective cluster head, calculated per round. | ADV_S | Number of advertise messages broadcast by cluster heads to surrounding nodes. |

| ADV_R | Number of advertise messages received by a node from nearby cluster heads. | JOIN_S | Number of join request messages sent by nodes to cluster heads for cluster formation. |

| JOIN_R | Number of join request messages received by cluster heads from their member nodes. | SCH_S | Number of TDMA schedule broadcast messages sent by cluster heads to nodes. |

| SCH_R | Number of TDMA schedule messages received from cluster heads by the nodes. | Rank | The order or rank of a node within the TDMA schedule during communication. |

| DATA_S | Number of data packets sent from a sensor node to its cluster head. | DATA_R | Number of data packets received by the cluster head from its sensor nodes. |

| Data_Sent_To_BS | Number of data packets transmitted from the cluster head to the base station. | dist_CH_To_BS | Distance between the cluster head and the base station used for energy computation. |

| send_code | Cluster sending code identifying the transmitting node within its cluster. | Expanded_Energy | Amount of energy consumed by the node during the previous communication round. |

| Attack_type | Target variable representing the attack category with five classes: Blackhole, Grayhole, Flooding, TDMA, and Normal. | – | – |

| Class | Label |

|---|---|

| Blackhole | 0 |

| Flooding | 1 |

| Grayhole | 2 |

| Normal | 3 |

| TDMA | 4 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning rate | |

| Batch size | 128 |

| Epochs | 30 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Regularization | |

| Dropout rate | – |

| Feature dimension | 16 |

| Hidden units (BiLSTM) | 64 per direction |

| Model | XAI | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | No | 97.00 | 83.60 | 82.60 | 82.00 |

| CNN + RNN | No | 97.04 | 98.79 | 96.48 | 96.86 |

| Naïve Bayes | No | 95.82 | 96.80 | 95.40 | 96.09 |

| Proposed model | Yes | 98.00 | 98.42 | 97.91 | 97.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Baniata, L.H.; ALDabbas, A.; Atwan, J.M.; Alahmer, H.; Elmasri, B.; Bunterngchit, C. A Dual-Attention CNN–GCN–BiLSTM Framework for Intelligent Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks. Future Internet 2026, 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010005

Baniata LH, ALDabbas A, Atwan JM, Alahmer H, Elmasri B, Bunterngchit C. A Dual-Attention CNN–GCN–BiLSTM Framework for Intelligent Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks. Future Internet. 2026; 18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaniata, Laith H., Ashraf ALDabbas, Jaffar M. Atwan, Hussein Alahmer, Basil Elmasri, and Chayut Bunterngchit. 2026. "A Dual-Attention CNN–GCN–BiLSTM Framework for Intelligent Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks" Future Internet 18, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010005

APA StyleBaniata, L. H., ALDabbas, A., Atwan, J. M., Alahmer, H., Elmasri, B., & Bunterngchit, C. (2026). A Dual-Attention CNN–GCN–BiLSTM Framework for Intelligent Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks. Future Internet, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010005