University Students’ Subjective Well-Being in Japan Between 2021 and 2023: Its Relationship with Social Media Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

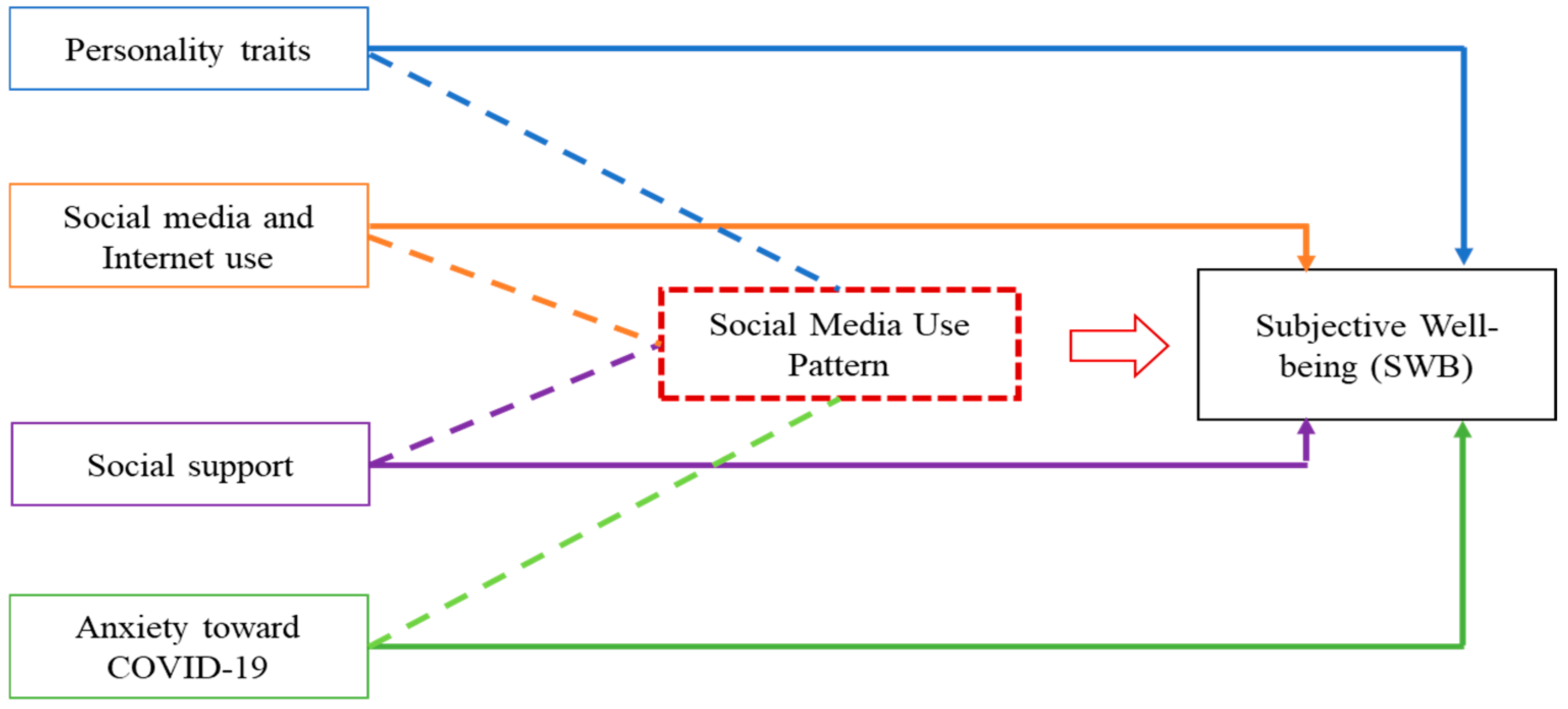

2. Research Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Young Adults’ Social Media Use in Japan

2.2. Young Adults’ Personality Traits, Social Media Use, and SWB in the World

2.3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Information About Participants

4.2. Usage of the Internet and Social Media

| Demographics | 2021 (n = 1681) | 2022 (n = 1292) | 2023 (n = 851) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internet Usage Time (in hours/month) 1 Computers Smartphones Tablets | 120.8 144.2 21.5 | 111.4 142.9 24.8 | 94.5 136.7 22.4 |

| LINE Usage Rate Overall Males Females | 99.4% 98.8% 100.0% | 98.8% 98.4% 99.1% | 99.2% 99.0% 99.5% |

| Twitter Usage Rate Overall Males Females | 86.1% 86.2% 85.9% | 83.3% 86.3% 80.2% | 83.5% 86.6% 81.0% |

| Instagram Usage Rate Overall Males Females | 70.8% 60.0% 81.1% | 74.1% 63.9% 84.1% | 77.3% 71.6% 83.8% |

| Facebook Usage Rate Overall Males Females | 10.9% 10.9% 9.3% | 6.3% 6.5% 6.2% | 6.0% 6.6% 5.4% |

| TikTok Usage Rate Overall Males Females | 14.0% 11.5% 16.4% | 15.8% 14.1% 17.4% | 18.7% 15.6% 21.3% |

| Discord Usage Rate Overall Males Females | 21.3% 30.9% 12.1% | 29.7% 41.1% 18.7% |

4.3. Effects of Personality Traits and Other Factors on SWB During the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.4. The Interaction Effect of Gender with Personality Traits and Other Variables on SWB

5. Discussion

5.1. Social Media Usage During COVID-19 Among University Students in Japan

| Pattern 1 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram) | Pattern 2 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram + TikTok) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 (n = 730) | 2022 (n = 472) | 2023 (n = 275) | 2021 (n = 175) | 2022 (n = 126) | |

| Age 2 | 0.08 # | 0.10 # | |||

| Living Condition 3 | −0.09 ** | −0.07 # | |||

| Generalized Trust | 0.10 ** | ||||

| Self-indeterminate | −0.08 ** | 0.29 *** | 0.32 *** | ||

| Self-establishment | 0.25 *** | 0.15 * | |||

| Self-independent | −0.09 # | ||||

| Self-variable | 0.07 * | 0.16 ** | |||

| Rejection Avoidance | −0.14 *** | −0.11 * | |||

| Praise Acquisition | 0.14 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.15 ** | 0.16 * |

| Self-appeal | −0.09 * | ||||

| Topic Avoidance | −0.17 ** | ||||

| Internet Usage Time via Smartphone | −0.17 * | ||||

| Internet Usage Time via Tablet | 0.08 * | ||||

| OCSs | 0.10 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.12 ** | 0.20 *** | 0.15 * |

| Twitter Monthly Usage | −0.08 * | ||||

| LINE Monthly Posting Frequency | 0.05 * | ||||

| Twitter Monthly Posting Frequency | −0.06 * | ||||

| Instagram Monthly Posting Frequency | 0.10 ** | ||||

| Anxiety Toward COVID-19 | |||||

| Depression Tendency | −0.28 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.17 ** | −0.40 *** |

| Social Support | 0.37 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.35 *** |

| Self-indeterminate × Gender | 0.24 ** | −0.30 * | |||

| Self-establishment × Gender | 0.17 * | ||||

| Self-variable × Gender | −0.51 ** | ||||

| Topic Avoidance × Gender | −0.17 * | 0.52 ** | |||

| Internet Usage Time via Computer × Gender | −0.09 * | ||||

| Internet Usage Time via Smartphone × Gender | 0.28 * | ||||

| Internet Usage Time via Tablet × Gender | −0.09 ** | ||||

| OCSs × Gender | −0.23 # | ||||

| Twitter Monthly Usage × Gender | 0.07 * | ||||

| Instagram Monthly Usage × Gender | 0.11 # | ||||

| Twitter Monthly Posting Frequency × Gender | 0.21 * | ||||

| Instagram Monthly Posting Frequency × Gender | −0.20 * | ||||

| Anxiety Toward COVID-19 × Gender | −0.28 ** | 0.22 * | |||

| Depression Tendency × Gender | −0.09 # | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.45 |

| F-value | 73.83 *** | 40.23 *** | 25.82 *** | 28.32 *** | 17.82 *** |

| Range of VIF | 1.04–1.68 | 1.02–2.02 | 1.05–2.83 | 1.11–2.00 | 1.07–1.16 |

5.2. Changes in Anxiety Toward COVID-19, Depression Tendency, Social Support, and SWB

5.3. Factors Influencing SWB from 2021 to 2023 and the Interaction with Gender

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Ho, K.K.W.; Ye, S.Y.; Chiu, D.K.W.; Sekiguchi, T. Digital transformation in remote learning and work—An externality of the COVID-19 pandemic. IEEE Internet Comput. 2024, 28, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. The relationship between burden caused by coronavirus (COVID-19), addictive social media use, sense of control and anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, T.; Chen, W.; Liao, Y. Social media use in China before and during COVID-19: Preliminary results from an online retrospective survey. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 140, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Lucock, M. The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey in the UK. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Larson, L.R.; Sharaievska, I.; Rigolon, A.; McAnirlin, O.; Mullenbach, L.; Cloutier, S.; Vu, T.M.; Thom-sen, J.; Reigner, N.; et al. Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, B.K.; Ayittey, F.K.; Sarkar, S.M. Impact of COVID-19 on psychology among the university students. Glob. Chall. 2020, 4, 2000038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C.; Holden, S.M.; Ariati, J. Social media and psychological well-being among youth: The multidimensional model of social media use. Clin. Child Fam. Rev. 2021, 24, 631–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-María, N.; Lara, E.; Forsman, A.K. Editorial: Relationship between subjective well-being and mental disorders across the lifespan. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1268287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications of Japan (総務省情報通信政策研究所). 令和5年度情報通信メディアの利用時間と情報行動に関する調査報告書 (Survey on Information and Communication Media USAGE time and Information Behavior in FY2023). 2024. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000976455.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Ho, K.K.W.; Ye, S.Y. University students’ social media usage and subjective well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Comparing similarities and differences from 2021 to 2022. IEICE Tech. Rep. 2023, 122, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cato, S.; Iida, T.; Ishida, K.; Ito, A.; Katsumata, H.; Mclwain, K.M.; Shoji, M. The bright and dark sides of social media usage during the COVID-19 pandemic: Survey evidence from Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 54, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Shimoura, K.; Nagai-Tanima, M.; Aoyama, T. The relationship between information sources, health literacy, and COVID-19 knowledge in the COVID-19 Infodemic: Cross-sectional online study in Japan. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e38332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Adachi, H.; Yamamoto, R.; Fujino, R.; Ishimaru, D.; Kanayama, D.; Sakagami, Y.; Akamine, S.; Marutani, N.; Mamiya, Y.; et al. Increased digital media use is associated with sleep problems among university students: A study during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 946265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.Y.; Ho, K.K.W. College students’ Twitter usage and psychological well-being from the perspective of generalised trust: Comparing changes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Libr. Hi Tech 2023, 41, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, T. The effect of social skills on loneliness through mediation of CMC social networks. Jpn. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 17, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.Y.; Ho, K.K.W.; Wakabayashi, K.; Kato, Y. Relationship between university students’ emotional expression on tweets and subjective well-being: Considering the effects of their self-presentation and online communication skills. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.Y.; Ho, K.K.W. Social media use and subjective well-being among university students in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Libr. Hi Tech, 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchi, M.; Festic, N.; Latzer, M. Digital overuse and subjective well-being in a digitized society. Soc. Media + Soc. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marttila, E.; Koivula, A.; Räsänen, P. Does excessive social media use decrease subjective well-being? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between problematic use, loneliness and life satisfaction. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, S.A. Facebook addiction and subjective well-being: A study of the mediating role of shyness and loneliness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. The impact of social media use types and social media addiction on subjective well-being of college students: A comparative analysis of addicted and non-addicted students. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 4, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. How does time spent on WeChat bolster subjective well-being through social integration and social capital? Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Gaskin, J.; Rost, D.H.; Gentile, D.A. The reciprocal relationship between passive social networking site (SNS) usage and users’ subjective well-being. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2018, 36, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienlin, T.; Masur, P.K.; Trepte, S. Reinforcement or displacement? The reciprocity of FTF, IM, and SNS communication and their effects on loneliness and life satisfaction. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2017, 22, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.Y.; Ho, K.K.W.; Zerbe, A. The effects of social media usage on loneliness and well-being: Analysing friendship connections of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 2021, 49, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.Y.; Ho, K.K.W. Would you be healthier if you had more social capital? Focusing on university students’ social media use in Japan. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, T.; Yamagishi, M. Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motiv. Emot. 1994, 18, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, K. The self and selection of friendship in high school students. Contemp. Sociol. Stud. 2011, 24, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Ohta, K.; Sugawara, K. Praise seeking and rejection avoidance need scales: Development and examination of validity. Jpn. J. Personal. 2003, 11, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M. A study of the characteristics of communication skills and online senders’ behavior. Bull. Joetsu Univ. Educ. 2018, 37, 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Kyoritsu Maintenance Co., Ltd. 学生のコロナ禍の3大不安は「感染・将来・友人と会えない」(The Three Major Anxieties of the Student’s COVID-19 Effects Are “Infection, Future, and I Can’t Meet My Friends). 2021. Available online: https://prtimes.jp/main/html/rd/p/000000091.000030012.html (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Shima, S.; Shikano, T.; Kitamura, T.; Asai, M. New self-rating scales for depression. Seishin Igaku 1985, 27, 717–723. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa, H.; Gondo, Y.; Masui, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Kawaai, C.; Otsuka, R.; Ogawa, M.; Takayama, M.; Imuta, H.; Suzuki, T. 日本語版「ソーシャル・サポート尺度」の信頼性ならびに妥当性—中高年者を対象とした検討 (Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the “social support scale”—A study for middle-aged and elderly people). J. Health Welf. Stat. 2007, 54, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Sagara, J.; Ikeda, M.; Kawamura, Y. Reliability and validity of subjective well-being scale. Jpn. J. Psychol. 2003, 74, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.K.; Salter, A. Embracing Discord? The rhetorical consequences of gaming platforms as classrooms. Comput. Compos. 2022, 65, 102729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenlein, M.; Anadol, E.; Farnsworth, T.; Hugo, H.; Hunichen, J.; Welte, D. Navigating the new era of influencer marketing: How to be successful on Instagram, TikTok, & Co. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 63, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherr, S.; Wang, K. Explaining the success of social media with gratification niches: Motivations behind daytime, nighttime, and active use of TikTok in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadivel, R.; Shoib, S.; El Halabi, S.; El Hayek, S.; Essam, L.; Bytyçi, D.G.; Karaliuniene, R.; Teixeira, A.L.S.; Nagendrappa, S.; Ramalho, R.; et al. Mental health in the post-COVID-19 era: Challenges and the way forward. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 34, e100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, V.; Pons, V.; Profeta, P.; Becher, M.; Brouard, S.; Foucault, M. Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: Panel evidence from eight countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27285–27291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, P.; Altrocchi, J.; House, C. Self-pluralism: Assessment and relations to adjustment, life changes, and age. J. Personal. 2000, 68, 347–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity and the Life Cycle; Norton, W.W. & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asano, T. Will SNS change “I”? In Mobile Phone of 21st Century; A Mature Mobile Society; Matsuda, M., Dobashi, S., Tsuji, I., Eds.; University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 117–148. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J.; Schouten, P. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyber Psychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, S. Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyber Psychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, S.; Kawai, D.; Sasaki, Y. Relationships between the use of emotional terms on social media, posting motives, and network structure: Focusing on positive and negative emotional terms in Twitter. Jpn. J. Lang. Soc. 2017, 20, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kewalramani, A.R. What Had COVID-19 Taught Us About Employee Engagement? Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/mt/en/pages/human-capital/articles/mt-employee-engagement-and-covid-19.html (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Kato, S.; Kato, Y. Timing of occurrence of negative emotions in LINE’s group chat: Relationship with the number of “friends” and “groups” of LINE. J. Jpn. Educ. Res. Soc. AI Era 2020, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Kato, Y.; Ozawa, Y. Reply speed as nonverbal cue in text messaging with a read receipt display function: Effects of messaging dependency on times until negative emotions occur while waiting for a reply. Int. J. Technol. Hum. Interact. 2020, 16, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.Y.; Toshimori, A.; Horita, T. The effects of personality traits on smartphone dependency and loneliness: A study of university students in Japan. J. Socio-Inform. 2018, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Period | Situation |

|---|---|---|

| The first state of emergency | 7 April 2020–25 May 2020 | All facilities were closed |

| The second state of emergency | 8 January 2021–21 March 2021 | Long period of stay-at-home and remote work |

| The third state of emergency | 25 April 2021–20 June 2021 | People started expressing exhaustion from the above requests |

| The fourth state of emergency | 12 July 2021–30 September 2021 | Tokyo Olympics were held without spectators |

| The first priority measure to prevent the spread of COVID-19 | 5 April 2021–30 September 2021 (12 April 2021–11 July 2021) | Tokyo Olympics were held without spectators |

| The second priority measure to prevent the spread of COVID-19 | 9 January 2022–21 March 2022 (21 January 2022–21 March 2022) | Measure ended. Japan reopened to foreigners gradually, and it became optional to wear masks from 13 March 2023. COVID-19 was reclassified as “Class V” from 8 May 2023. |

| Demographics | 2021 (n = 1681) | 2022 (n = 1292) | 2023 (n = 851) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (in percentage) Males Females Others | 48.0% 51.0% 1.0% | 47.6% 51.1% 1.3% | 48.1% 50.2% 1.8% |

| Average Age | 19.7 (SD:1.38) | 20.0 (SD: 1.46) | 20.2 (SD: 1.68) |

| Academic Year First year Second year Third year Fourth year (including over) Others (including working or further studies) | 34.1% 24.4% 20.1% 21.3% - | 26.4% 22.8% 20.3% 25.2% 5.4% | 29.4% 16.6% 22.1% 17.7% 14.2% |

| Residence Status Living alone Living with friends Living with family Room share Others | 70.0% 2.6% 24.6% 2.8% 0.1% | 69.3% 3.6% 24.3% 2.7% 0.1% | 71.0% 3.5% 23.0% 2.4% 0.1% |

| Pattern 1 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram) | Pattern 2 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram + TikTok) | Pattern 3 1 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram + Discord) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 (n = 737) | 2022 (n = 477) | 2023 (n = 276) | 2021 (n = 176) | 2022 (n = 127) | 2023 (n = 95) | 2021 | 2022 (n = 119) | 2023 (n = 122) | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Males Females Others | 294 436 7 | 180 292 5 | 109 166 1 | 64 111 1 | 53 73 1 | 30 63 2 | 79 37 3 | 84 36 2 | |

| Average Usage Time (hours/month) | |||||||||

| LINE | 40.3 | 37.7 | 37.4 | 46.4 | 42.5 | 42.6 | 38.1 | 37.9 | |

| 55.9 | 46.4 | 44.8 | 45.0 | 47.2 | 50.8 | 76.4 | 63.9 | ||

| 39.3 | 36.9 | 38.9 | 50.5 | 43.9 | 44.5 | 32.5 | 34.9 | ||

| Discord | 45.9 | 40.3 | |||||||

| TikTok | 47.4 | 45.6 | 47.7 | ||||||

| Post Frequency (days/month) 2 | |||||||||

| LINE | 20.2 | 17.0 | 17.5 | 19.6 | 18.0 | 19.1 | 18.4 | 20.4 | |

| 12.5 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 11.0 | 10.7 | 18.4 | 17.4 | ||

| 6.8 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 11.0 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 7.0 | 7.9 | ||

| Discord | 9.2 | 10.0 | |||||||

| TikTok | 5.4 | 3.1 | 2.5 | ||||||

| LINE | TikTok | Discord 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Number of users Males Females | 797 858 | 605 654 | 405 425 | 696 737 | 531 529 | 354 346 | 484 706 | 393 555 | 293 358 | 93 142 | 87 115 | 64 91 | 190 80 | 168 80 |

| Common hobby (%) | 21.5 12.7 | 20.2 15.4 | 21.2 15.8 | 45.3 41.7 | 38.8 34.6 | 44.1 42.2 | 26.9 30.5 | 29.8 29.0 | 28.0 33.2 | 5.4 6.3 | 6.9 8.7 | 1.6 9.9 | 42.3 35.0 | 44.6 22.5 |

| Fulfilling lives (friends/selves) (%) | 11.3 7.5 | 15.4 11.9 | 16.1 11.3 | 21.3 19.5 | 18.7 15.4 | 22.0 20.8 | 37.6 50.4 | 38.7 52.8 | 41.3 55.0 | 11.1 5.0 | 10.7 5.0 | |||

| Photos, videos, etc. (%) | 21.3 19.9 | 21.8 21.4 | 24.9 23.8 | 31.9 30.5 | 26.6 23.7 | 29.2 26.3 | 49.6 62.5 | 53.4 64.3 | 49.8 62.0 | 4.3 6.3 | 8.1 12.2 | 4.7 8.8 | 21.6 10.0 | 22.0 10.0 |

| Replies to friends (%) | 38.8 38.5 | 43.3 40.4 | 50.4 41.9 | 30.3 32.8 | 23.3 24.8 | 31.6 26.3 | 13.4 19.7 | 12.5 16.4 | 17.1 18.2 | 5.4 0.7 | 53.2 37.5 | 46.4 37.5 | ||

| Daily friendship (%) | 27.0 19.8 | 26.5 23.7 | 33.6 23.5 | 18.3 20.5 | 17.4 19.3 | 21.8 19.1 | 20.3 29.9 | 20.9 30.5 | 21.8 32.7 | 26.8 12.5 | 19.1 8.8 | |||

| Reports and grades (%) | 10.0 4.6 | 11.7 7.0 | 9.9 6.8 | 12.2 9.4 | 9.8 10.1 | 12.4 11.0 | 7.4 3.8 | 8.3 3.8 | ||||||

| Masochistic (%) | 18.1 17.4 | 15.5 17.1 | 17.2 16.5 | |||||||||||

| Job hunting (%) | 1.1 5.0 | |||||||||||||

| Others (%) | 8.2 9.5 | 7.9 8.4 | 1.2 5.2 | 6.3 10.0 | 8.9 10.0 | |||||||||

| Do not post (%) | 37.8 48.5 | 32.9 42.4 | 26.2 41.4 | 37.9 37.2 | 34.2 34.4 | 38.1 47.4 | 31.4 21.8 | 31.0 23.6 | 33.5 22.4 | 81.7 93.7 | 89.7 93.9 | 90.6 90.1 | 21.6 45.0 | 21.4 43.8 |

| Scales | 2021 (n = 1681) | 2022 (n = 1292) | 2023 (n = 851) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Trust (0.81/0.82/0.81) | 20.46 | 20.48 | 20.57 |

| Self-consciousness and Friendship: Self-indeterminate factor (0.76/0.76/0.78) Self-establishment factor (0.74/0.73/0.74) Self-independent factor (0.69/0.67/0.73) Self-variable factor (0.63/0.60/0.60) | 3.41 3.65 2.93 3.51 | 3.69 3.50 3.00 3.35 | 3.74 3.43 3.01 3.27 |

| Desire for Self-presentation and Admiration: Rejection avoidance factor (0.85/0.86/0.86) Praise acquisition factor (0.83/0.83/0.82) Self-appeal factor (0.82/0.82/0.81) Topic avoidance factor (0.72/0.75/0.72) | 2.68 3.12 3.55 3.88 | 3.57 3.16 2.72 3.87 | 3.55 3.24 2.77 3.89 |

| Online Communication Skills (OCSs) (0.75/0.78/0.80) | 55.11 | 55.43 | 55.50 |

| Anxiety toward COVID-19 (0.74/0.76/0.82) | 24.55 | 22.50 | 17.93 |

| Depression Tendency 2 | 3.24 | 3.57 | 2.94 |

| Social Support (0.93/0.92/0.92) | 66.68 | 68.98 | 69.70 |

| SWB (0.86/0.90/0.90) | 48.68 | 49.53 | 51.85 |

| Pattern 1 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram) | Pattern 2 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram + TikTok) | Pattern 3 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram + Discord) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 (n = 737) | 2022 (n = 477) | 2023 (n = 276) | 2021 (n = 176) | 2022 (n = 127) | 2023 (n = 95) | 2021 | 2022 (n = 119) | 2023 (n = 122) | |

| Generalized Trust Males Females | 20.63 21.17 20.27 | 20.59 21.14 20.34 | 20.73 21.10 20.50 | 20.39 20.81 20.16 | 20.72 20.40 20.96 | 20.14 20.57 19.92 | 20.04 20.15 20.08 | 21.06 21.39 20.36 | |

| Self-consciousness and Friendship: | |||||||||

| Self-indeterminate Males Females | 3.45 3.30 3.56 | 3.67 3.78 3.60 | 3.71 3.89 3.59 | 3.43 3.48 3.40 | 3.68 3.75 3.63 | 3.81 3.84 3.83 | 3.64 3.70 3.50 | 3.73 3.78 3.62 | |

| Self-establishment Males Females | 3.67 3.76 3.62 | 3.51 3.30 3.63 | 3.42 3.20 3.56 | 3.67 3.70 3.65 | 3.57 3.49 3.63 | 3.55 3.44 3.58 | 3.53 3.36 3.84 | 3.34 3.25 3.49 | |

| Self-independent Males Females | 2.90 2.75 3.00 | 2.96 2.81 3.04 | 3.01 2.94 3.06 | 2.82 2.82 2.81 | 2.87 2.73 2.97 | 2.94 2.79 3.00 | 2.89 2.77 3.17 | 2.91 2.89 2.97 | |

| Self-variable Males Females | 3.57 3.48 3.64 | 3.47 3.37 3.52 | 3.34 3.33 3.34 | 3.61 3.88 3.45 | 3.32 3.27 3.34 | 3.33 3.20 3.39 | 3.32 3.30 3.36 | 3.17 3.20 3.14 | |

| Desire for Self-presentation and Admiration: | |||||||||

| Rejection Avoidance Males Females | 2.71 2.94 2.56 | 3.63 3.40 3.77 | 3.57 3.41 3.68 | 2.87 3.13 2.73 | 3.59 3.44 3.68 | 3.65 3.44 3.74 | 3.53 3.42 3.71 | 3.63 3.55 3.85 | |

| Praise Acquisition Males Females | 3.16 3.33 3.05 | 3.20 3.29 3.14 | 3.31 3.53 3.16 | 3.32 3.45 3.25 | 3.18 3.38 3.01 | 3.17 3.22 3.16 | 3.33 3.35 3.28 | 3.29 3.40 3.06 | |

| Self-appeal Males Females | 3.62 3.49 3.70 | 2.75 2.90 2.65 | 2.76 2.99 2.59 | 3.66 3.61 3.69 | 2.80 3.05 2.60 | 2.81 2.68 2.88 | 2.92 2.93 2.85 | 2.96 2.99 2.89 | |

| Topic Avoidance Males Females | 3.91 3.78 4.00 | 3.95 3.69 4.11 | 3.90 3.83 3.95 | 3.92 3.78 4.01 | 3.80 3.58 3.95 | 3.91 3.74 3.98 | 3.76 3.61 4.07 | 3.93 3.90 3.99 | |

| Online Communication Skills (OCSs) Males Females | 55.58 54.62 56.31 | 56.53 55.89 56.93 | 56.44 55.80 56.78 | 56.86 56.59 57.00 | 55.58 55.30 55.71 | 55.57 56.23 55.51 | 53.54 52.96 55.27 | 53.30 53.81 52.39 | |

| Anxiety Toward COVID-19 Males Females | 24.87 24.30 25.30 | 22.73 22.31 22.94 | 17.95 16.98 18.61 | 27.19 25.58 28.14 | 24.63 24.34 24.78 | 17.66 15.93 18.37 | 22.08 21.10 23.62 | 17.67 17.12 19.00 | |

| Depression Tendency Males Females | 3.28 2.87 3.50 | 3.18 2.68 3.39 | 2.46 1.87 2.77 | 2.86 2.33 3.17 | 3.46 2.79 3.95 | 3.14 2.27 3.22 | 4.77 4.09 5.78 | 3.53 3.20 4.25 | |

| Social Support Males Females | 67.99 66.62 69.00 | 69.93 69.17 70.67 | 71.29 72.15 70.66 | 70.04 70.09 69.90 | 71.69 71.09 72.04 | 70.17 69.13 71.08 | 67.45 67.95 67.62 | 69.31 68.74 70.83 | |

| SWB Males Females | 49.19 49.54 49.00 | 50.58 50.67 50.62 | 52.61 54.10 51.76 | 50.24 51.33 49.62 | 49.99 51.26 49.15 | 51.92 52.63 51.94 | 47.18 47.99 46.57 | 50.52 50.68 50.42 | |

| Pattern 1 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram) | Pattern 2 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram + TikTok) | Pattern 3 (LINE + Twitter + Instagram + Discord) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 (n = 730) | 2022 (n = 472) | 2023 (n = 275) | 2021 (n = 175) | 2022 (n = 126) | 2023 (n = 95) | 2021 | 2022 (n = 116) | 2023 (n = 120) | |

| Gender 2 | −0.07 * | ||||||||

| Age | 0.12 * | −0.16 ** | |||||||

| Living Condition 3 | −0.08 ** | ||||||||

| Generalized Trust | 0.04 # | 0.10 ** | 0.14 * | ||||||

| Self-indeterminate | 0.29 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.18 * | 0.17 ** | 0.25 *** | ||||

| Self-establishment | 0.24 *** | 0.13 * | |||||||

| Self-independent | −0.09 * | 0.14 # | |||||||

| Self-variable | 0.07 * | −0.10 # | |||||||

| Rejection Avoidance | −0.16 *** | −0.13 ** | |||||||

| Praise Acquisition | 0.14 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.12 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.22 ** | ||||

| Self-appeal | −0.08 # | ||||||||

| Topic Avoidance | 0.14 * | ||||||||

| Internet Usage Time via Computer | 0.13 * | ||||||||

| Internet Usage Time via Tablet | 0.14 * | ||||||||

| OCSs | 0.10 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.14 ** | 0.15 * | 0.19 * | ||||

| LINE Monthly Usage Time | −0.17 # | ||||||||

| Twitter Monthly Usage Time | −0.07 # | ||||||||

| Instagram Monthly Usage Time | 0.19 * | ||||||||

| LINE Posting Frequency | 0.05 * | ||||||||

| Instagram Posting Frequency | 0.09 ** | 0.10 # | |||||||

| Anxiety Toward COVID-19 | −0.16 * | ||||||||

| Depression Tendency | −0.29 *** | −0.26 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.45 *** | −0.40 *** | −0.44 *** | −0.28 *** | |

| Social Support | 0.37 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.22 ** | 0.41 *** | 0.43 *** | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.66 | |

| F-value | 141.92 *** | 48.05 *** | 45.39 *** | 35.97 *** | 26.69 *** | 16.90 *** | 48.99 *** | 29.34 *** | |

| Range of VIF | 1.00–1.31 | 1.01–1.80 | 1.03–1.38 | 1.06–1.50 | 1.05–1.22 | 1.05–1.57 | 1.03–1.35 | 1.11–1.40 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, S.; Ho, K.K.W. University Students’ Subjective Well-Being in Japan Between 2021 and 2023: Its Relationship with Social Media Use. Future Internet 2025, 17, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17030126

Ye S, Ho KKW. University Students’ Subjective Well-Being in Japan Between 2021 and 2023: Its Relationship with Social Media Use. Future Internet. 2025; 17(3):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17030126

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Shaoyu, and Kevin K. W. Ho. 2025. "University Students’ Subjective Well-Being in Japan Between 2021 and 2023: Its Relationship with Social Media Use" Future Internet 17, no. 3: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17030126

APA StyleYe, S., & Ho, K. K. W. (2025). University Students’ Subjective Well-Being in Japan Between 2021 and 2023: Its Relationship with Social Media Use. Future Internet, 17(3), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17030126