Abstract

Nowadays, the majority of everyday computing devices, irrespective of their size and operating system, allow access to information and online services through web browsers. However, the pervasiveness of web browsing in our daily life does not come without security risks. This widespread practice of web browsing in combination with web users’ low situational awareness against cyber attacks, exposes them to a variety of threats, such as phishing, malware and profiling. Phishing attacks can compromise a target, individual or enterprise, through social interaction alone. Moreover, in the current threat landscape phishing attacks typically serve as an attack vector or initial step in a more complex campaign. To make matters worse, past work has demonstrated the inability of denylists, which are the default phishing countermeasure, to protect users from the dynamic nature of phishing URLs. In this context, our work uses supervised machine learning to block phishing attacks, based on a novel combination of features that are extracted solely from the URL. We evaluate our performance over time with a dataset which consists of active phishing attacks and compare it with Google Safe Browsing (GSB), i.e., the default security control in most popular web browsers. We find that our work outperforms GSB in all of our experiments, as well as performs well even against phishing URLs which are active one year after our model’s training.

1. Introduction

While the exploitation of trust or personality traits such as agreeableness or obedience is not a new phenomenon, the pervasiveness of the Internet has brought a new conceptual framework in which such activities can be conducted. Comparing those to a face-to-face setting, the former provides several advantages for the attacker, such as anonymity and a greater geographical reach. Once with this contextual shift, the term phishing has been popularised. Phishing is described as a scam by which an Internet user is manipulated into disclosing personal or confidential information that the attacker can use illicitly [1].

In its primitive form, a phishing attack requires elementary technical knowledge. The main skills required are the ones easily transferable from manipulation or deceit in face-to-face interaction. This factor, among others, have contributed to the popularity growth of phishing attacks in the past twenty-five years.

The increased use of phishing as an attack vector is reflected in the numbers registered by the Anti-Phishing Working Group [2]. Their archives open with the reports from across 2004. These add up to 33.5 thousand unique registered phishing attacks with missing data for September 2004. After fifteen years, the APWG registered 479,468 unique phishing attacks in 2019. Besides the growth in numbers, these reports outline a clear advancement in the technical aspects of registered phishing campaigns as well. One example of this is the adoption of Transport Layer Security (TLS) used to serve phishing websites over Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS). Reported usage has grown from close to 0% in 2016, to 68% by the end of the third quarter of 2019 [2].

The majority of Internet users today use their smartphone to surf the web instead of any other computing device. This adds another enabler for a successful phishing attack. This holds true as using a mobile phone to surf the web reduces the width of the address bar, making URL inspection harder for the user. In addition, users have a predisposition of being a victim of phishing attacks, irrespective of their sex, age, education, browser, operating system, or hours of computer usage [3].

While investigating the same issue, Rachna Dhamija, J. D. Tygar et al. [3] show that even in the best-case scenarios when a user is expecting a phishing attack, the best phishing website deceived 90% of the participants. Domain squatting [4], the popular attack where malicious parties register domain names that are purposefully similar to popular domains is also manifesting in every form (e.g., typosquatting, homophone squatting, homograph squatting, bitsquatting and combosquatting). To make the matter worse, the use of HTTPS, which is perceived as a popular indicator of a trustworthy website, is utilised by threat actors while mounting their phishing attacks (APWG [2]). This allows the threat actors to create the feeling of a safe and secure website, which coupled with the content served to the user can increase the likelihood of the attack’s success.

The out-of-the box, and often the only, safeguard against phishing attacks a web user has is the browser’s denylist. For the majority of the web users this is the technology that is provided by Google, namely Google Safe Browsing (GSB). Usage statistics show that Google Chrome, Apple Safari, and Mozilla Firefox comprise 86.59% of the browser’s market share [5]. These browsers use GSB denylist service in an attempt to provide to their users protection against phishing attacks. An alternative anti-phishing safeguard used in Microsoft products such as Windows Explorer and Edge is Microsoft Defender SmartScreen. SmartScreen is embedded in the Windows operating system and delivers protection against a wide range of threats. The phishing protection provided through Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Edge browsers accounts for 4.25% of the market share.

Threat actors who conduct phishing attacks as part of their tactics, techniques and procedures contribute to a dynamic environment, where phishing links appear and are taken down on a daily basis. Given that the reported median phishing webpage lifespan is of less than twenty-four hours [6], synchronisation speed and frequency of denylist updates are crucial factors in defending against this type of threat. For this reason web browsers synchronise their denylist frequently in an attempt to have the most up-to-date threat information. Nonetheless, previous work has uncovered that the aforementioned technologies provide a sub-optimal update and classification process in terms of execution time and thus limited phishing protection to its users [7,8,9,10].

For this reason, the relevant literature includes security controls that use machine learning in order to defend against phishing [11]. In this work, we propose and evaluate a phishing detection engine, which uses supervised machine learning in order to detect phishing attacks based on a novel combination features that are extracted from the URL. This allows us to avoid any delays which stem from the computation of features that need access to third-party resources, such as access to WHOIS records. In summary, our work makes the following contributions:

- We train, optimise and evaluate a phishing detection engine which relies on supervised machine learning, based on features that stem from the URL. Our feature selection process includes features that have been proven suitable by the literature, coupled with new ones that we propose and evaluate. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to use the Levenshtein distance as a similarity index feature for training a range of machine learning algorithms in this domain. We also, revisit the use of suggestive vocabulary, which was used in the past [12], as one of our features.

- We evaluate the performance of our phishing detection engine over time by classifying active phishing attacks that were reported on PhishTank, without model retraining. We find that the performance of the classification is not affected by time, as well as it significantly outperforms the protection that is offered by GSB.

2. Related Work

Mitigating phishing, with either prevention or detection, has been well-studied in the academic literature. The following subsections focus on the discussion of software-based approaches, as user awareness is considered out of scope for this work.

2.1. Rule-Based Phishing Detection

Rule-based anti-phishing approaches classify websites as malicious or legitimate based on a set of pre-defined rules. Since the ruleset is the centrepiece of the detection system, its performance is tightly linked to its design. As a consequence, the focus is set on rule selection and conditional relationship setting.

Ye Cao et al. [13] proposed an automated allowlist capable of updating itself with records of the IP addresses of each website visited that features a login page. If a user attempts to submit data through such a login user interface, they get a warning that they are doing so on a webpage outside of the allowlist. The proposed solution uses the Naive Bayesian as the classifier, which has delivered high effectiveness in previous studies on anti-spam [14] and junk email filters [15]. After the decision has been made, the classification is expected to be further confirmed by the user. Although the proposed solution delivered an impressive performance with true positives rate 100% and false negatives rate 0%, this approach relies on the involvement of the users and cannot discover new phishing webpages.

Another allowlist based approach is presented by A. K. Jain and B.B. Gupta [16], which achieves phishing detection using a two-phase method. The proposed system logically splits webpages into not visited and re-visited. The first module is triggered when a page is re-visited and consists of a domain lookup within the allowlist. If the domain name is found, the system matches the IP address to deliver the decision. When the domain name cannot be found in the allowlist, the system uses statistical analysis of the number of hyperlinks pointing to a foreign domain. After extraction, the system examines the features from the hyperlinks to take the decision. The proposed system covers a variety of phishing attacks (e.g., DNS poisoning, embedded objects, zero-hour attack), and its experimental results report a 86.02% true-positive rate and 1.48% false-negative rate.

Yue Zhang et al. [17] proposed an adaptation of the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) information retrieval algorithm for detecting phishing webpages in a content-based approach called CANTINA. CANTINA uses the TF-IDF algorithm to extract the most frequently used five words, which are then fed into a search engine. The website’s domain name is then compared with the top N domain names resulted from the search, and if there is a match, the website is labelled as legitimate. To lower the rate of false-positives, they included a set of heuristics checking the age of the domain, the presence of characters such as @ signs, dashes, dots or IP addresses in the URL. Furthermore, it features some content-based checks such as inconsistent well-known logos, links referenced and forms present. The experimental results show a true positive rate of 97% and a false positive rate of 6%. After the addition of these heuristics, the false positive rate decreased to 1% but so did the true positive rate, which decreased to 89%. Finally, one should note that CANTINA’s effectiveness is tightly linked to the use of the English language.

Rami Mohammad and Lee McCluskey [18] present an intelligent rule-based phishing detection system, whose ruleset is produced through data mining. The study begins with a proposed list of seventeen phishing features derived from previous work on anti-phishing detection systems. These are then fed into different rule-based classification algorithms, each of which utilises a different methodology in producing knowledge. The conclusion presents C4.5 [19] as the algorithm that produced the most effective ruleset. The extracted set presents features related to: (a) the request URL, (b) domain age, (c) HTTPS and SSL, (d) website traffic, (e) subdomain and multi subdomain, (f) presence of prefix or suffix separated by “–” in the domain, and (g) IP address usage. The limitation of this work is the reliance on third-party services providing information about the age of the domain, webpage traffic, and DNS record data. Furthermore calibrating the thresholds for each feature requires complex statistical work.

S.C. Jeeva and E.B. Rajsingh [20] approach phishing detection by firstly focusing on the extraction of quintessential indicators, statistically proven to be found in phishing websites. The work then presents a set of heuristics based on the aforementioned statistical investigations and analysis, which are translated into fourteen rules responsible for URL classification. Similar to the work of Rami Mohammad and Lee McCluskey [18], the identified rules are fed into two data mining algorithms (Apriori and Predictive Apriori), to discover meaningful associations between them. The work provided two sets resulted from associative rule mining and reported an experimental accuracy of 93% when using the ruleset mined by the apriori algorithm.

2.2. Machine-Learning Based Phishing Detection

Machine learning-based solutions centre around the processes of feature extraction and the training of machine learning models. These features take the shape of information from different parts of the website, such as the URL or the Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) content. This subsection will briefly discuss a variety of machine learning approaches to anti-phishing detection systems, and the essential takeaways from the studies covered.

A. Le et al. [21] propose PhishDef—a system which performs on-the-fly classification of phishing URLs based on lexical features and adaptive regularisation of weights (AROW [22]). The AROW algorithm allows the calibration of the classification mechanism upon making a wrong prediction. As a result, the predictions will be of high accuracy even when the trained model is provided with noisy data. Furthermore, PhishDef uses an online classification algorithm, as opposed to a batch-based one. Online classification algorithms continuously retrain their model when encountering new data, instead of just delivering the prediction. PhishDef reports an accuracy of 95% with noise ranging from 5% to 10%, and above 90% when noise is between 10% and 30%. It is worth noting that the aforementioned performance of PhishDef comes with low computational and memory requirements.

Guang Xiang et al. [23] extend CANTINA ([17]) by adding a feature-rich machine learning module. The iteration is named CANTINA+ and it aims to address the high false-positive rate of its predecessor. Besides machine learning techniques, this enhanced iteration brings focus on search engines, and the HTML Document Object Model (DOM), adding several checks on brand, domain, hostname search and HTML attributes. Besides the inherited trade-offs of CANTINA, the authors state that one of the limitations of CANTINA+ is the incapability of delivering predictions on phishing websites that are composed of images, thus offering no text which can be analysed. Furthermore, compared to CANTINA, while it manages to provide improved accuracy rate of 92%, it is still prone to considerable false positives rate.

Ling Li et al. [24] present a multi-stage detection system that aims to both pro-actively and reactively thwart banking botnets. The first module of this model is an early warning detection module which supervises the malicious-looking newly registered domains. The second module does spear phishing detection using a machine learning model trained on different variations of popular domains such as bitsquatting, omission, and other alteration techniques. Although this work is focused more on banking botnets, the approach used in URL variations detection and spear-phishing protection is well designed.

Li Yukun et al. [25] take a different approach by utilising a stacked machine learning model that surpasses the capability of single model implementations of anti-phishing detection systems. The work provides a thorough comparison of the proposed stack composed of Gradient Boosting Decision trees [26], XGBoost [27], and LightGBM [28] and single models using algorithms such as Support Vector Machine, nearest neighbour classifier, decision trees, and Random Forest. To measure inter-rater reliability for qualitative (categorical) items and select the best candidates for the stacking model the authors used Cohen’s kappa static [29] and the lower average error. This lowered the false-positive and false-negative rates of the stacking model, when compared to all its components individually, achieving an accuracy rate of 97.3%, false positive rate of 1.61% and a false negative rate of 4.46%.

Similarly, Rendall et al. [30] implemented and evaluated a two-layered detection framework that identifies phishing domains based on supervised machine learning. The authors considered four supervised machine learning algorithms, i.e., Multilayer Perceptron, Support Vector Machine, Naive Bayes, and Decision Tree, which were trained and evaluated using a dataset consisting of 5995 active phishing and 7053 benign domains. Their detection engine used static and dynamic features derived from domain and DNS packet-level data. Finally, the authors discussed the features’ ability to resist tampering from a threat actor who is trying to circumvent the classifiers, e.g., by typosquatting, as well as their applicability in a production environment.

Sahingoz Koray Ozgur et al. [31] investigate the possibility of a real-time anti-phishing system by training seven different classification algorithms with natural language processing (NLP), word vector and hybrid features. In doing so, Sahingoz Koray Ozgur et al. [31] state the lack of a worldwide acceptable test dataset for effectiveness comparison between phishing solutions, and proceeds to construct one containing 73,575 URLs of which 34,600 legitimate and 37,175 malicious. This dataset is used to conduct comparisons between previous work in the field and the selected classification algorithms (Decision Trees, Adaboost, Kstar, K-Nearest Neighbour, Random Forest, Sequential Minimal Optimization and Naive Bayes). The most effective combination discovered is the Random Forest algorithm trained with NLP features. It achieved an experimental accuracy of 97.98% in URL classification, while being language and third-party service independent, and achieving real-time execution and detection of new websites. Finally, the authors’ experiments suggest that the NLP features seem to improve accuracy across the majority of machine learning algorithms covered in their work.

M. A. Adebowale et al. [10] use an artificial neural network named Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS [32]) which is trained with integrated text, image, and frame features. The work presents a brief comparison between the proposed solution and numerous other anti-phishing detection systems. The works builds a set of 35 features from phishing websites analysis and related work while also comparing their efficiency. These are then bound in sets and fed into ANFIS, SVM, and KNN algorithms to study their performance. The ANFIS-based hybrid solution (including text, image and frame features) delivered an accuracy of 98.30%. Although the work considers the previously mentioned solution as the conclusive, the ANFIS text-based classification records an accuracy of 98.55%. Besides this, throughout the study, there is evidence that text-based detection systems tend to outperform image-based, frame-based and hybrid ones.

Mahmood Moghimi and Ali Yazdian Varjani [33] present a solution based on a selection of seventeen web content features fed into a Support Vector Machine (SVM) learning algorithm. The most effective features are chosen based on accuracy, error, Cohen’s Kappa Static [29], sensitivity, and the F-Measure [29]. Before evaluation, the features are fed into the SVM algorithm to extract knowledge under the shape of rules to increase comprehensibility. By doing this, the importance and effect of each feature can be extracted. The authors benchmark the features and discuss the consequences of omitting different rules, outlining the ones with the biggest contribution in making accurate predictions. The study reports an impressive experimental result of 99.14% accuracy, with only 0.86% false negative. Moreover, the proposed solution achieves zero-day phishing detection and both third party service and language independence. Christou et al. [34] also used SVM and Random Forest implemented in the Splunk Platform to detect malicious URLs. They reached 85% precision and 87% recall in the case of Random Forests, while SVM achieved up to 90% precision and 88% recall.

Finally, Mouad Zouina and Benaceur Outtaj [35] examined how similarity indexes influence the accuracy of Support Vector Machine models. The aim of the study is the production of a lightweight anti-phishing detection system, suitable for devices such as smartphones. The work first presents a set of base URL features composed of: (a) the number of hyphens, (b) number of dots, (c) the number of numerical characters, and (d) IP presence. The authors extended this set by adding the: (a) classic Levenshtein distance, (b) normalised Levenshtein distance, (c) Jaro Winkler distance, (d) the longest common subsequence, (e) Q-Gram distance, and (f) the Hamming distance, while measuring their influence on accuracy. Their solution achieves an accuracy of 95% and presents 2000 records (1000 legitimate and 1000 malicious) on which it performs all the calculations mentioned earlier when classifying a URL. The authors conclude that the Hamming distance is the most effective feature from the studied set improving the overall recognition rate by 21.8%.

The literature includes a number of works that facilitate machine learning to mitigate phishing as a threat. From the above works, it is evident that supervised machine learning algorithms, e.g., SVM, Naive Bayes, perform well in a binary classification problem like phishing detection. Nonetheless, contrary to our work, the majority of the literature is using machine learning algorithms that are trained and evaluated in balanced datasets. This means that the evaluation took place using a scenario that is not realistic [11]. Furthermore, multiple data sources have been used for feature selection. We differentiate from prior works in the literature by proposing a new combination of features, which is evaluated over time. Finally, while the use of Levenshtein distance has been explored in the previous literature, e.g., explored but not used in the SVM classifier of [35], to the best of our knowledge we are the first to use it as a feature in phishing detection model.

2.3. Google Safe Browsing

Google Safe Browsing (GSB) is a deny list that is used in the three most popular browsers in terms of market share, i.e., Google Chrome, Apple’s Safari and Mozilla Firefox. Priyam Kaur Sandhu and Sanjam Singla [36] describe the mechanism behind GSB and capture the differences between the different API versions. However, the study dates back to 2015, and as a consequence, the comparison includes only the first three versions. Since then, version four has been released, marking the end of support for version two and three. Google [37] does not mention any fundamental changes to the version four API but details a series of adjustments focusing towards the growth in usage of mobile devices, where previous work has demonstrated the absence [38,39] or the limited protection that is offered by denylist as a security control [7,8,9]. The new GSB API is optimised for the challenges of the mobile environment, i.e.: the limited power, network bandwidth and poor quality of service. Moreover, the protection per bit is maximised, due to cellular data being a direct expense to the user.

3. Methodology

In order to build the phishing detection engine our work explored the use of supervised machine learning algorithms that have been frequently used in relevant literature [11], namely Naive Bayes [40], Decision Tree [41], Random Forest [42], Support Vector Machine [43], and Multi-Layer Perceptron [44]. These algorithms are trained using Python 3 and the SciKitLearn library [45]. The comparison of the machine learning models performance utilizes a set of metrics which are commonly used in this domain, i.e., (i) precision, (ii) sensitivity, (iii) F- Measure, (iv) Accuracy, (v) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, and (vi) Confusion matrix.

The metrics above are using True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), True Negatives (TN), and False Negatives (FN) for their calculations. TP classify URLs pointing to phishing websites, correctly, as phishing and TN classify benign URLs, correctly, as benign. FP misclassify benign URLs as phishing and FN misclassify phishing URLs as benign URLs. A system is said to be precise (1) when it delivers a high level of correct prediction values. Sensitivity (2), also known as recall, outlines the system’s predisposition in classifying a legitimate URL as being malicious. As the system increases in sensitivity, it reduces the number of false-negatives it produces. For clarification, precision is the ratio between all adequate classification errors and all classification errors. In contrast, recall is the ratio of all classification errors and all existing errors. The F-Measure (3) is the harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity. It is a composed metric which penalises the extreme values and is meant to provide a single measurement for a system which illustrates the level of optimisation. The accuracy (4) measures the ratio of true-positives and true-negatives. Finally, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve illustrates how well a model is capable of distinguishing between a phishing and a benign URL and the Confusion matrix offers a view of the classification performance details of the model.

The best-performing models were selected for both hyperparameter tuning and further experimentation with feature selection. Model optimisation is performed using GridSearchCV which performs an exhaustive search over specified parameters and selects the best performing model.

The dataset used for training the classifiers is based on the datasets from [46] and PhishTank. It includes 100,000 URLs that were collected in April 2020 and fed into the training phase with a 80/20 split between training and testing data respectively. Specifically, it consists of the first 40,000 benign URLs from Kumar Siddharth [46] and 60,315 phishing URLs from PhishTank.

3.1. Feature Selection

Our work uses a new combination of features consisting of features (F1-F10) that have been used for phishing detection [11] and proposes F11 and F12. These are summarized in Table 1 along with their descriptions. For the majority of the features, their computation is straightforward based on their description.

Table 1.

Summary of features used.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of URL length over the training dataset.

F8-F10 flag the presence of the most popular suggestive vocabulary in the (i) subdomain, (ii) domain, and (iii) path sections of the URL [12]. To identify the most popular suggestive vocabulary we measured their word frequency with the use of valid phishing URLs from PhishTank. These are split in the format of <subdomain>.<domain>/<path>?<query>. These sections are further probabilistically split using natural language processing (NLP) based on English unigram frequencies. The words that resulted from this process are sorted based on their frequency. It is worth noting that the exploration of the suggestive vocabulary of the query segment showed overlaps with the one used in benign URLs, thus, introducing a lot false positives. As such, our work only considers the lists of suggestive words from the subdomain, domain and path section of the URL. Furthermore, the path section of the URLs is searched for popular domains, as it is a common practice in phishing URLs to use the target domain or brand in the path under the form of “www.example.com/brand/signin.html”. If no suggestive word is found in the path, the first 2500 domains are searched throughout the path URL section.

Finally, F11 and F12 are based on the similarity index between the URL’s domain and subdomain, and the top 25K benign domains from [47]. This feature directly targets the use of domain obfuscation techniques, i.e., as those in Table 3. These are commonly used by phishing URLs with the aim to trick the users that they are accessing trusted, i.e., known brand domain. To this end the Levenshtein distance between the target URL and the top 25,000 benign domains is used. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to use the Levenshtein distance as a feature in phishing detection model. Specifically, based on our analysis, if the Levenshtein distance for the domain section (i.e., F11) is lower than six and greater than zero, then the URL is flagged as suspicious. For the subdomain section (i.e., F12), if the distance is lower than three, then the URL is flagged as suspicious. It is worth noting that our experimentation suggested that subdomains closer to popular domain names are more suspicious than different variations of a domain. Moreover, zero distances on the subdomain must not ignored as these represent the presence of a benign domain in the subdomain section of a given URL.

Table 3.

Domain variation techniques.

3.2. Model Selection and Tuning

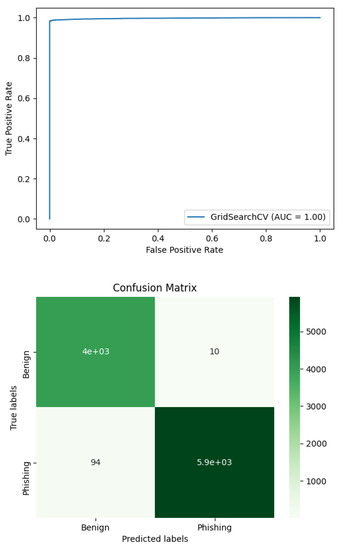

Based on the F1 scores of the algorithms (Table 4), Random Forest was the best candidate algorithm to be selected. The F1-score is used here as it is fit for generalising performance. Furthermore, Figure 1 presents both the ROC and confusion matrix for the Random Forest model. The maximum area under the curve (AOC) points out that the model can easily distinguish between the two classes of URLs. The confusion matrix reveals that it is uncommon for the model to mislabel URLs; only 104 URLs out of 10 thousand URLs were misclassified.

Table 4.

F-measure results of models’ training.

Figure 1.

ROC and confusion matrix of the Random Forest model.

Progressing to the next phase, we conducted the process of hyperparameter tuning or optimisation which consists of training a model with different values for its parameters. Trying different permutations of values for these parameters influences prediction accuracy, thus improving overall performance. It is worth noting that hyperparameter tuning is computationally expensive. For this reason, only the three algorithms with the best performance were selected for optimisation, namely: (a) Random Forest, (b) Support Vector Machine, and (c) Multi-Layer Perceptron.

During the optimisation of the Random Forest classifier, the number of n_estimators is increased to raise the number of decision trees. By doing so, the model can deliver better predictions at the expense of both training and prediction time. As such, the number of n_estimators is set to either 150, 295 or 350. Next, the max_depth of each decision tree is set to be either 15, 18 or 21. The last optimisation involves the max_features parameter. This sets the number of maximum features provided to each tree to auto and sqrt.

Tuning the SVM classifier involves searching for the best performing C parameter, which influences the misclassification threshold of the model. A classifier with a greater C value will use a smaller-margin hyperplane, rendering the model less prone to delivering wrong predictions. However, a bigger C value will increase the chance of overfitting. Finally, the values of the C fed into the GridSearchCV are 10, 100 and 1000.

Given the opaque nature of the training process of neural networks, the calibration of the Multi-Layer Perceptron matches a hit-or-miss experimentation. As such, different models have been trained using most of the optimisation parameters that the MLP classifier takes as input (see Appendix A).

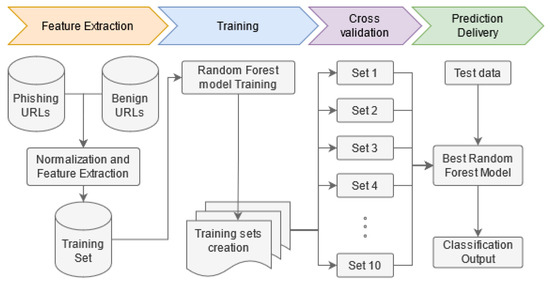

Finally, our results suggest that Random Forest remains the best performing algorithm, having a slight performance increase upon optimisation (see Table 5). Figure 2 summarizes the methodology that has been described in this section, applied to the selected model, i.e., Random Forest.

Table 5.

Comparison of optimised models.

Figure 2.

High-level description of the methodology applied to Random Forest model.

4. Evaluation

Our phishing detection engine was evaluated with a dataset of 380,000 benign and phishing URLs. This dataset included 305,737 benign URLs and 74,436 phishing URLs. We note that the use of an imbalanced dataset for this evaluation allowed us to evaluate the selected classifier in a realistic scenario [11]. This holds true as real traffic has proportionally more benign URLs compared to the phishing ones.

Our results suggest (Table 6), that our detection engine continues to perform very well using this imbalanced dataset. The high accuracy shows that our proposed model shows little confusion in classifying URLs, either benign or phishing. Moreover, during our experiments the model’s sensitivity was slightly higher than precision. This means that our model tends to produce false positives more frequently than false negatives. This is an acceptable trade-off, as frequent false positives would only mean irritation to the user, when benign web sites are classified as phishing. On the contrary, a higher false negative rate would mean that the model would miss active phishing attacks, which could lead to a security breach.

Table 6.

Optimised Random Forest results on the 380,000 mixed records dataset.

The performance of our work in detecting phishing URLs over time was further evaluated by classifying phishing URLs on a daily basis for six consecutive days (i.e., 5–10 May 2020), as well as individual days after several months, i.e., 15 November 2020 and 25 April 2021 (see Table 7). During this experiments, every day we used the latest URLs provided by PhishTank at the time of testing. These included all the confirmed online and active phishing attacks by the PhishTank community at the time of our experiment. Our results were compared with the performance of Google Safe Browsing (GSB), which is the default protection that is offered by the most popular web browsers at the time of our experiments, namely Chrome, Firefox and Safari. To access the most up to date threat information from GSB we used its online query functionality instead of relying to local browser caches, which might not contain latest GSB data [7]. Our experiments, which are summarized on Table 7, suggest that our phishing detection engine outperforms GSB, i.e., on average 94% accuracy compared to 45%.

Table 7.

Evaluation of accuracy over time using PhishTank.

5. Conclusions

Phishing is one of the main attack vectors that is often used by attackers in the current threat landscape. In this work, we proposed a phishing detection engine that uses supervised machine learning on features extracted from URLs. In doing so, we experimented, configured and optimised different supervised machine learning algorithms that are typically used throughout this area of work. Contrary to previous works in the literature, we evaluated the work with an imbalanced dataset, where the number of benign URLs are considerable more than the ones hosting a phishing attack. This allowed us to evaluate the protection that is offered in a realistic scenario, as such a ratio of benign and phishing URLs is more likely to occur in a real system.

Furthermore, we evaluated the performance of the phishing detection over time. This involved the evaluation of phishing detection after several days or months, without model retraining. Our experiments uncovered that the detection capability of our model remains similar even if it is evaluated against a dataset that is available several months after its training. This suggests that a thorough feature selection and model tuning, as the one described in this work, could allow an organisation to avoid frequent model retraining, which is expensive in a production environment. For future work we would like to explore the effectiveness of our methodology on other datasets, as well as the experimentation with more novel features and their influence. Additionally, we would like to investigate the robustness of our methodology against adversarial attacks that are frequently used by the malicious parties. Having finalized the feature list and fortified our solution against malicious activities our goal is the inclusion of our phishing detection engine as a component of a system that is deployed in a real-world production environment where competitive solutions seem to under perform.

Author Contributions

A.B., A.M. and N.P. contributed to the conceptualization and methodology of the manuscript. A.B. performed the data preparation and assisted A.M. with writing, N.P. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable, the study does not report any data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Models’ Configuration

Appendix A.1. Naive Bayes

"name": "Naive Bayes", "filename": "naive_bayes", "model": GaussianNB()

Appendix A.2. Decision Tree

"name": "Decision Tree",

"filename": "decision_tree",

"model": DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=1)

Appendix A.3. Random Forest

"name": "Random Forest",

"filename": "random_forest",

"model": GridSearchCV(

RandomForestClassifier(random_state=1),

[

{

"n_estimators": [150, 295, 350],

"max_features": ["auto"],

"min_samples_split": [8, 12],

"max_depth": [15, 18, 21],

}

],

cv=5,

)

Appendix A.4. Support Vector Machine

"name": "Support Vector Machine",

"filename": "support_vector",

"model": GridSearchCV(

SVC(kernel="rbf", random_state=1),

[{"C": [1, 10, 100, 1000],}],

cv=5,

)

Appendix A.5. Multilayered Perceptron

"name": "Neural Network",

"filename": "ml_perceptron",

"model": GridSearchCV(

MLPClassifier(max_iter=2500),

[

{

"hidden_layer_sizes": [

(25, 50, 25),

(50, 50, 50),

(50, 100, 50),

(100,),

],

"activation": ["tanh", "relu"],

"solver": ["sgd", "adam"],

"alpha": [0.0001, 0.05],

"learning_rate": ["constant", "adaptive"],

}

],

cv=5,

)

References

- Merriam-Webster. Phishing. 2020. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/phishing (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- APWG. Phishing Activity Trends Reports. 2019. Available online: https://apwg.org/trendsreports/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Dhamija, R.; Tygar, J.D.; Hearst, M. Why Phishing Works. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kintis, P.; Miramirkhani, N.; Lever, C.; Chen, Y.; Romero-Gómez, R.; Pitropakis, N.; Nikiforakis, N.; Antonakakis, M. Hiding in plain sight: A longitudinal study of combosquatting abuse. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2017; pp. 569–586. [Google Scholar]

- Globalstats. Browser, OS, Search Engine Including Mobile Usage Share. 2020. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Sheridan, K. As Phishing Kits Evolve, Their Lifespans Shorten. 2019. Available online: https://www.darkreading.com/threat-intelligence/as-phishing-kits-evolve-their-lifespans-shorten/d/d-id/1336220 (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Virvilis, N.; Mylonas, A.; Tsalis, N.; Gritzalis, D. Security Busters: Web browser security vs. rogue sites. Comput. Secur. 2015, 52, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virvilis, N.; Tsalis, N.; Mylonas, A.; Gritzalis, D. Mobile devices: A phisher’s paradise. In Proceedings of the 2014 11th International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT), Vienna, Austria, 28–30 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tsalis, N.; Virvilis, N.; Mylonas, A.; Apostolopoulos, T.; Gritzalis, D. Browser blacklists: The Utopia of phishing protection. Available online: https://www.infosec.aueb.gr/Publications/ICETE%202014%20Browser%20Blacklists_new.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Adebowale, M.; Lwin, K.; Sánchez, E.; Hossain, M. Intelligent web-phishing detection and protection scheme using integrated features of Images, frames and text. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 115, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Baki, S.; El Aassal, A.; Verma, R.; Dunbar, A. SoK: A comprehensive reexamination of phishing research from the security perspective. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 22, 671–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garera, S.; Provos, N.; Chew, M.; Rubin, A.D. A Framework for Detection and Measurement of Phishing Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2007 ACM Workshop on Recurring Malcode, Alexandria, VA, USA, 2 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Han, W.; Le, Y. Anti-Phishing Based on Automated Individual White-List. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM Workshop on Digital Identity Management, Alexandria, VA, USA, 31 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Androutsopoulos, I.; Koutsias, J.; Chandrinos, K.V.; Spyropoulos, C.D. An Experimental Comparison of Naive Bayesian and Keyword-Based Anti-Spam Filtering with Personal e-Mail Messages. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Athens, Greece, 24–28 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sahami, M.; Dumais, S.; Heckerman, D.; Horvitz, E. A Bayesian Approach to Filtering Junk E-Mail. In Proceedings of the AAAI’98 Workshop on Learning for Text Categorization, Madison, WI, USA, 26–27 July 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Gupta, B. A Novel Approach to Protect against Phishing Attacks at Client Side Using Auto-Updated White-List; EURASIP J. on Info. Security: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hong, J.I.; Cranor, L.F. Cantina: A Content-Based Approach to Detecting Phishing Web Sites. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on World Wide Web, Banff, AB, Canada, 8–12 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, R.M.; Thabtah, F.; McCluskey, L. Intelligent rule-based phishing websites classification. IET Inf. Secur. 2014, 8, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Improved Use of Continuous Attributes in C4.5. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 1996, 4, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeva, S.; Rajsingh, E. Intelligent phishing url detection using association rule mining. Hum. Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.; Markopoulou, A.; Faloutsos, M. PhishDef: URL names say it all. In Proceedings of the 2011 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM, Shanghai, China, 10–15 April 2011; pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crammer, K.; Kulesza, A.; Dredze, M. Adaptive Regularization of Weight Vectors. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 22; Bengio, Y., Schuurmans, D., Lafferty, J.D., Williams, C.K.I., Culotta, A., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 414–422. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, G.; Hong, J.; Rose, C.P.; Cranor, L. CANTINA+: A Feature-Rich Machine Learning Framework for Detecting Phishing Web Sites. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2011, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Gao, Z.; Silas, M.A.; Lee, I.; Doeuff, E.A.L. An AI-based, Multi-stage detection system of banking botnets. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.08276. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Yuan, H.; Liu, W. A stacking model using URL and HTML features for phishing webpage detection. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 94, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3146–3154. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, I.H.; Frank, E.; Hall, M.A. Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rendall, K.; Nisioti, A.; Mylonas, A. Towards a Multi-Layered Phishing Detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahingoz, O.K.; Buber, E.; Demir, O.; Diri, B. Machine learning based phishing detection from URLs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 117, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.R. ANFIS: Adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1993, 23, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, M.; Varjani, A.Y. New rule-based phishing detection method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 53, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, O.; Pitropakis, N.; Papadopoulos, P.; McKeown, S.; Buchanan, W.J. Phishing URL Detection Through Top-level Domain Analysis: A Descriptive Approach. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.06599. [Google Scholar]

- Zouina, M.; Outtaj, B. A novel lightweight URL phishing detection system using SVM and similarity index. Hum. Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, P.K.; Singla, S. Google Safe Browsing—Web Security. IJCSET 2015, 5, 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Evolving the Safe Browsing API. 2016. Available online: https://security.googleblog.com/2016/05/evolving-safe-browsing-api.html (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Mylonas, A.; Tsalis, N.; Gritzalis, D. Evaluating the manageability of web browsers controls. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Security and Trust Management, Egham, UK, 12–13 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tsalis, N.; Mylonas, A.; Gritzalis, D. An intensive analysis of security and privacy browser add-ons. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Risks and Security of Internet and Systems, Lesvos, Greece, 1 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rish, I. An empirical study of the naive Bayes classifier. In Proceedings of the IJCAI 2001 Workshop on Empirical Methods in Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, WA, USA, 4–6 August 2001; Volume 3, pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, P.H.; Hauska, H. The decision tree classifier: Design and potential. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Electron. 1977, 15, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, G.; Scornet, E. A random forest guided tour. Test 2016, 25, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, D.X. Analysis of support vector machine classification. J. Comput. Anal. Appl. 2006, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, K.; Stinchcombe, M.; White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 1989, 2, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. Malicious And Benign URLs. 2019. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/siddharthkumar25/malicious-and-benign-urls (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Majestic. Top one million benign websites. 2019. Available online: https://majestic.com/reports/majestic-million (accessed on 11 June 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).