In today’s ubiquitous society, we experience a situation where digital informing and mediated communication are dominant. The contemporary online media landscape consists of the web forms of the traditional media along with new online native ones and social networks. Content generation and transmission are no longer restricted to large organizations and anyone who wishes may frequently upload information in multiple formats (text, photos, audio, or video) which can be updated just as simple. Especially, regarding social media, which since their emergence have experienced a vast expansion and are registered as an everyday common practice for thousands of people, the ease of use along with the immediacy they present made them extremely popular. In any of their modes, such as microblogging (like Twitter), photos oriented (like Instagram), etc., they are largely accepted as fast forms of communication and news dissemination through a variety of devices. The portability and the multi-modality of the equipment employed (mobile phones, tablets, etc.), enables users to share, fast and effortless, personal or public information, their status, and opinions via the social networks. Thus, communications nodes that serve many people have been created minimizing distances and allowing free speech without borders; since more voices are empowered and shared, this could serve as a privilege to societies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, in an area that is so wide and easily accessible to large audiences many improper intentions with damaging effects might be met as well, one of which is hate speech.

It is widely acknowledged that xenophobia, racism, gender issues, sexual orientation, and religion among others are topics that trigger hate speech. Although no universally agreed definition of hate speech has been identified, the discussion originates from discussions on freedom of expression, which is considered one of the cornerstones of a democracy [

9]. According to Fortuna and Nunes (2018, p. 5): “Hate speech is language that attacks or diminishes, that incites violence or hate against groups, based on specific characteristics such as physical appearance, religion, descent, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, gender identity or other, and it can occur with different linguistic styles, even in subtle forms or when humor is used” [

10]. Although international legislation and regulatory policies based on respect for human beings prohibit inappropriate rhetoric, it finds ways to move into the mainstream, jeopardizing values that are needed for societal coherence and in some cases relationships between nations, since hate speech may fuel tensions and incite violence. It can be met towards one person, a group of persons, or to nobody in particular [

11] making it a hard to define and multi-dimensional problem. Specifically, in Europe as part of the global North, hate speech is permeating public discourse particularly subsequent to the refugee crisis, which mainly -but not only- was ignited around 2015 [

12]. In this vein, its real-life consequences are also growing since it can be a precursor and incentive for hate crimes [

13].

Societal stereotypes enhance hate speech, which is encountered both in real life and online, a space where discourses are initiated lately around the provision of free speech without rules that in some cases result to uncontrolled hate speech through digital technologies. Civil society apprehensions led to international conventions on the subject and even further social networking sites have developed their own services to detect and prohibit such types of expressed rhetoric [

14], which despite the platforms’ official policies as stated in their terms of service, are either covert or overt [

15]. Of course, a distinction between hate and offensive speech must be set clear and this process is assisted by the definition of legal terminology. Mechanisms that monitor and further analyze abusive language are set in efforts to recognize aggressive speech expanding on online media, to a degree permitted by their technological affordances. The diffusion of hateful sentiments has intrigued many researchers that investigate online content [

11,

13,

15,

16] initially to assist in monitoring the issue and after the conducted analysis on the results, to be further promoted to policy and decision-makers, to comprehend it in a contextualized framework and seek for solutions.

Paz, Montero-Díaz, and Moreno-Delgado (2020, p. 8) refer to four factors, media used to diffuse hate speech, the subject of the discourse, the sphere in which the discourse takes place, and the roots or novelty of the phenomenon and its evolution that each one offers quantification and qualification variables which should be further exploited through diverse methodologies and interdisciplinarity [

17]. In another context, anthropological approaches and examination of identities seek for the genealogy through which hate speech has been created and sequentially moved to digital media as well as the creation of a situated understanding of the communication practices that have been covered by hate speech [

13]. Moreover, on the foundation to provide a legal understanding of the harm caused by hateful messages, communication theories [

18] and social psychology [

19] are also employed. Clearly, the hate speech problem goes way back in time, but there are still issues requiring careful attention and treatment, especially in today’s guzzling world of social media and digital content, with the vast and uncontrollable way of information publishing/propagations and the associated audience reactions.

1.1. Related Work: Hate Speech in Social Media and Proposed Algorithmic Solutions

Hate speech has been a pivotal concept both in public debate and in academia for a long time. However, the proliferation of online journalism along with the diffusion of user-generated content and the possibility of anonymity that it allows [

20,

21] has led to the increasing presence of hate speech in mainstream media and social networks [

22,

23].

During the recent decades, media production has often been analyzed through the lens of citizen participation. The idea of users’ active engagement in the context of mainstream media was initially accompanied by promises of enhancing democratization and strengthening bonds with the community [

24,

25]. However, the empirical reality of user participation was different from the expectations, as there is lots of dark participation, with examples ranging from misinformation and hate campaigns to individual trolling and cyberbullying; a large variety of participation behaviors are evil, malevolent, and destructive [

22]. Journalists identify hate speech as a very frequently occurring problem in participatory spaces [

8]. Especially comments, which are considered an integral part of almost every news item [

26], have become an important section for hate speech spreading [

27].

Furthermore, an overwhelming majority of journalists argue that they frequently come upon hate speech towards journalists in general, while most of them report a strong increase in hate speech personally directed at them [

28]. When directed at professionals, hate speech can cause negative effects both on journalists themselves and journalistic work: it might impede their ability to fulfill their duties as it can put them under stark emotional pressure, trigger conflict into newsrooms when opinions diverge on how to deal with hateful attacks or even negatively affect journalists’ perception of their audience [

28]. Hence, not rarely, professionals see users’ contributions as a necessary evil [

27] and are compelled to handle a vast amount of amateur content in tandem with their other daily tasks [

29].

To avoid problems, such as hate speech, and protect the quality of their online outlets, media organizations adopt policies that establish standards of conduct and restrict certain behaviors and expressions by users [

30]. Community managers are thus in charge of moderating users’ contributions [

31], by employing various strategies for supervising, controlling, and enabling content submission [

32]. When pre-moderation is followed, every submission is checked before publication and high security is achieved. However, this method requires considerable human, financial, and time resources [

27]. On the other hand, post-moderation policies lead to a simpler and more open approach but can lower the quality [

33], exposing the platform to ethical and legal risks. Apart from manual moderation, some websites utilize artificial intelligence techniques to tackle this massive work automatically [

34], while others implement semi-automatic approaches that assist humans through the integration of machine learning into the manual process [

35].

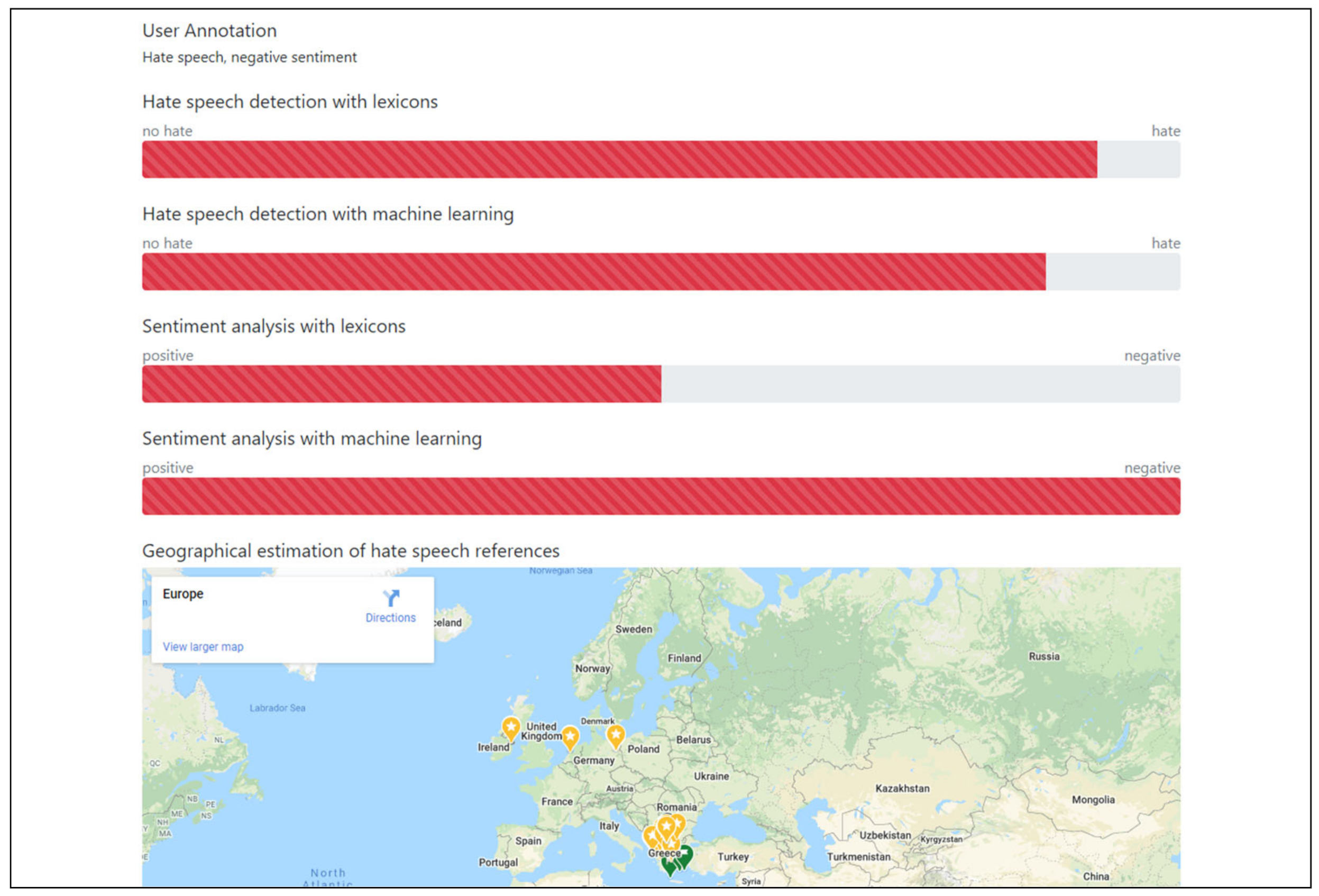

The automation of the process of hate speech detection relies on the training and evaluation of models, using annotated corpora. The main approaches include lexicon-based term detection and supervised machine learning. Lexicons contain a list of terms, along with their evaluation concerning the relation to hate speech. The terms are carefully selected and evaluated by experts on the field, and they need to be combined with rule-based algorithms [

36,

37,

38]. Such algorithms are based on language-specific syntax and rules. Computational models such as unsupervised topic modeling can lead to insight regarding the most frequent terms that allow further categorization of the hate-related topics [

39,

40]. In supervised machine learning approaches, models are trained using annotated corpora. Baseline approaches rely on bag-of-words representations combined with machine learning algorithms [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. More recent methods rely on deep learning and word embeddings [

42,

43]. The robustness of a supervised machine learning algorithm and its ability to generalize for the detection of hate in unseen data relies on the retrieval of vast amounts of textual data.

Big data analytics of social media contents is an emerging field for the management of the huge volumes that are created and expanded daily [

44]. Most social media services offer dedicated application programming interfaces (APIs) for the collection of posts and comments, to facilitate the work of academics and stakeholders. Using a dedicated API, or a custom-made internet scraper makes it easy to retrieve thousands of records automatically. Twitter is the most common choice, due to the ease-of-use of its API, and its data structure that makes it easy to retrieve content relevant to a specific topic [

36,

37,

41]. While textual analysis is the core of hate speech detection, metadata containing information about the record (e.g., time, location, author, etc.) may also contribute to model performance. Hate speech detection cannot be language-agnostic, which means that a separate corpus or lexicon and methodology needs to be formed for every different language [

36,

37,

45]. Moreover, a manual annotation process is necessary, which, inevitably introduces a lot of human effort, as well as subjectivity [

36]. Several annotation schemes can be found in literature, differing in language, sources (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, etc.), available classes (e.g., hate speech, abusive language, etc.), and ranking of the degree of hate (e.g., valence, intensity, numerical ranking, etc.) [

37]. The selected source itself may influence the robustness of the algorithmic process. For instance, Twitter provides a maximum message length, which can affect the model fitting in a supervised training process [

36]. Multi-source approaches indicate the combination of different sources for analytics [

46]. In [

47] for example, Twitter data from Italy are analyzed using computational linguistics and the results are visualized through a Web platform to make them accessible to the public.

1.2. Project Motivation and Research Objectives

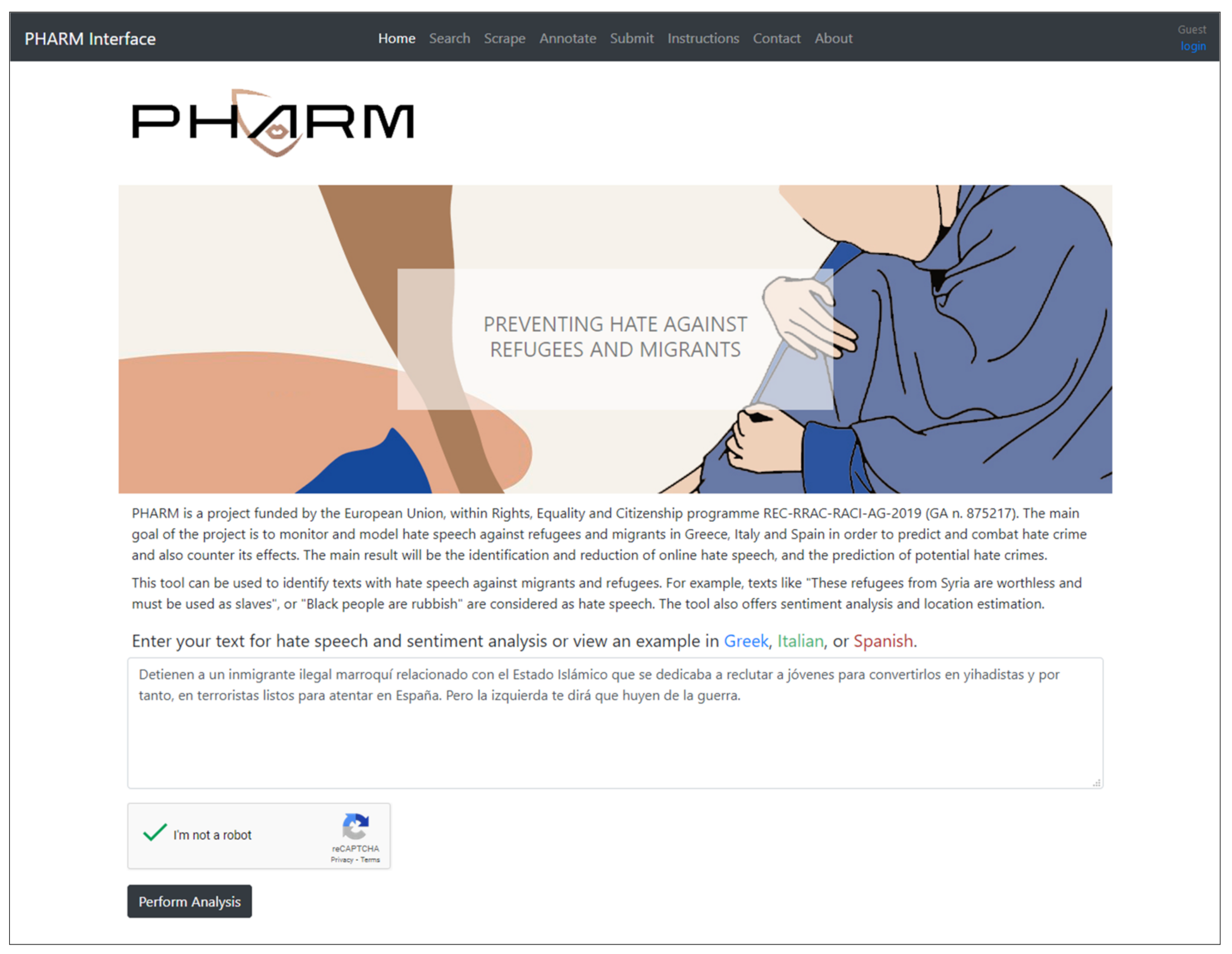

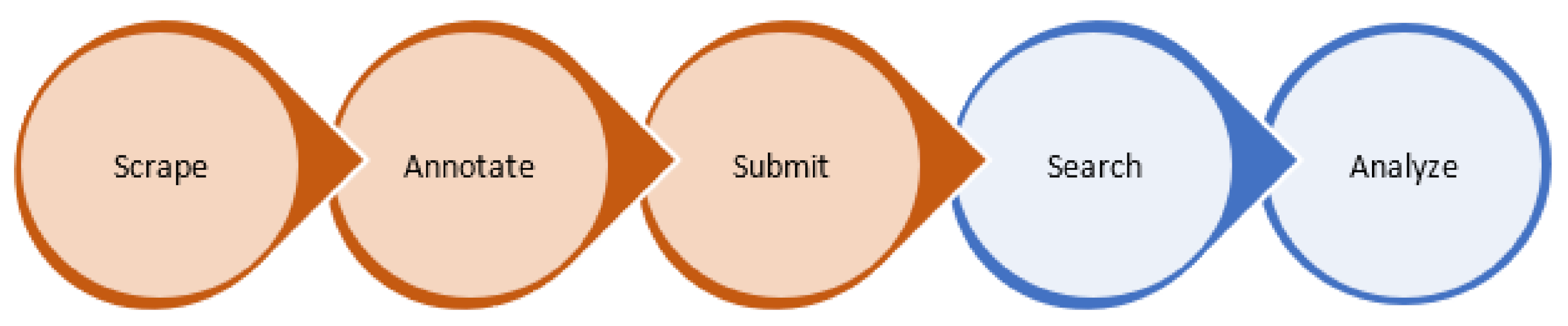

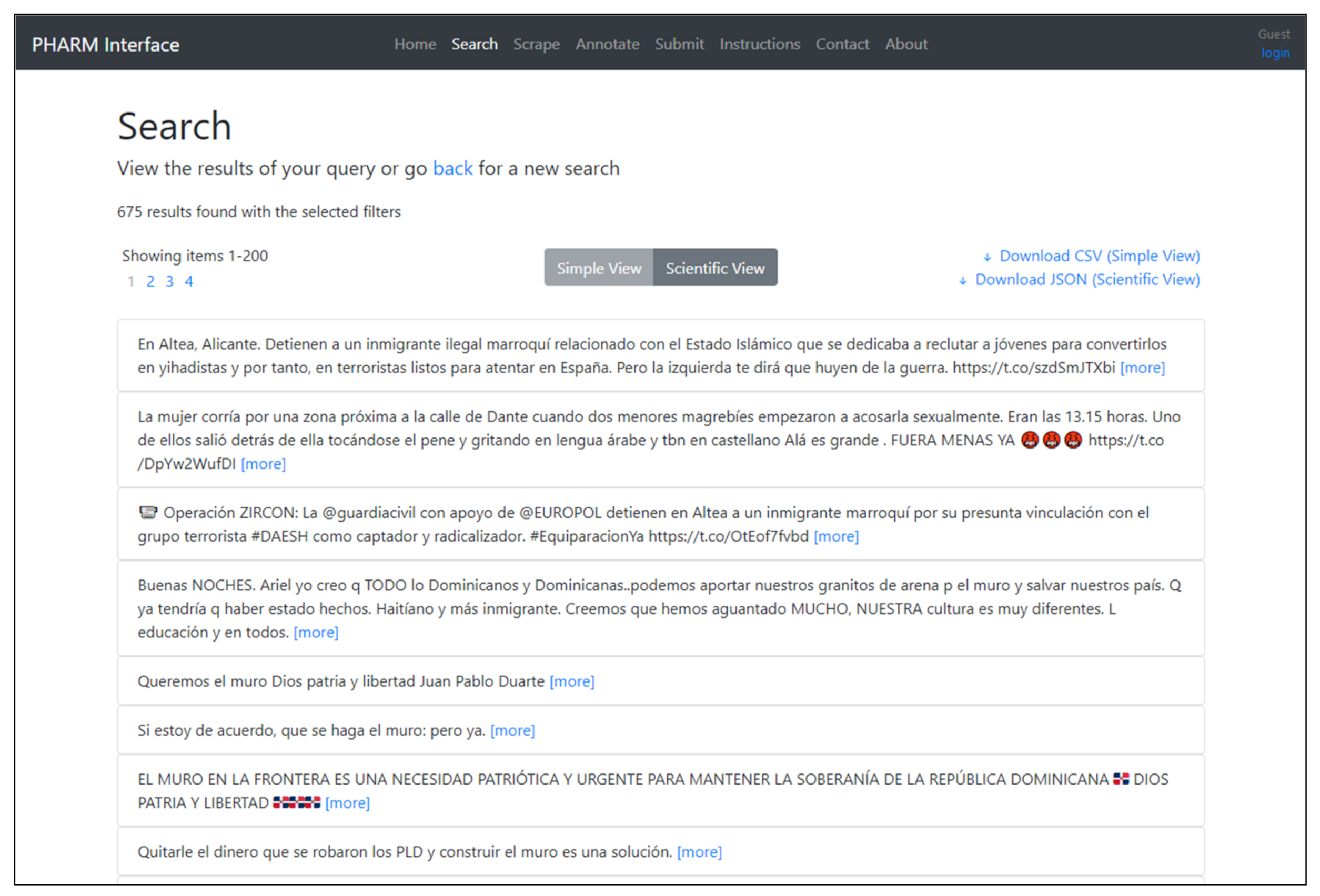

Based on the preceding analysis, there is missing a multilingual hate-speech detection (and prevention) web-service, which individuals can utilize for monitoring informatory streams with questionable content, including their own user-generated content (UGC) posts and comments. More specifically, the envisioned web environment targets to offer an all-in-one service for hate speech detection in text data deriving from social channels, as part of the Preventing Hate against Refugees and Migrants (PHARM) project. The main goal of the PHARM project is to monitor and model hate speech against refugees and migrants in Greece, Italy, and Spain to predict and combat hate crime and also counter its effects using cutting-edge algorithms. This task is supported via intelligent natural language processing mechanisms that identify the textual hate and sentiment load, along with related metadata, such as user location, web identity, etc. Furthermore, a structured database is initially formed and dynamically evolving to enhance precision in subsequent searching, concluding in the formulation of a broadened multilingual hate-speech repository, serving casual, professional, and academic purposes. In this context, the whole endeavor should be put into test through a series of analysis and assessment outcomes (low-/high-fidelity prototypes, alpha/beta testing, etc.) to monitor and stress the effectiveness of the offered functionalities and end-user interface usability in relation to various factors, such as users’ knowledge and experience background. Thus, standard application development procedures are followed through the processes of rapid prototyping and the anthropocentric design, i.e., the so-called logical-user-centered-interactive design (LUCID) [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Therefore, audience engagement is crucial, not only for communicating and listing the needs and preferences of the targeted users but also for serving the data crowdsourcing and annotating tasks. In this perspective, focusing groups with multidisciplinary experts of various kinds are assembled as part of the design process and the pursued formative evaluation [

50,

51,

52], including journalists, media professionals, communication specialists, subject-matter experts, programmers/software engineers, graphic designers, students, plenary individuals, etc. Furthermore, online surveys are deployed to capture public interest and people’s willingness to embrace and employ future Internet tools. Overall, following the above assessment and reinforcement procedures, the initial hypothesis of this research is that it is both feasible and innovative to launch semantic web services for detecting/analyzing hate speech and emotions spread through the Internet and social media and that there is an audience willing to use the application and contribute. The interface can be designed as intuitively as possible to achieve high efficiency and usability standards so that it could be addressed to broader audiences with minimum digital literacy requirements. In this context, the risen research questions (RQ) elaborated to the hypotheses are as follows:

RQ1: Is the PHARM interface easy enough for the targeted users to comprehend and utilize? How transparent the offered functionalities are?

RQ2: What is the estimated impact of the proposed framework on the journalism profession and the anticipated Web 3.0 services? Are the assessment remarks related to the Journalism profession?