Latent Structure Matching for Knowledge Transfer in Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- A novel task matching algorithm, namely LSM, is proposed for RL to derive latent structures of value functions of tasks, and align the structures for similarity estimation. Structural alignment permits efficient matching of large number of tasks, and locating the correspondences of tasks.

- (ii)

- Based on LSM, we present an improved exploration strategy, that is built on the knowledge obtained from the highly-matched source task. This improved strategy reduces random exploration in value function space of tasks, thus effectively improving the performance of RL agents.

- (iii)

- A theoretical proof is given to verify the improvement of exploration strategy with the latent structure matching-based knowledge transfer (Please see Appendix B).

2. Related Work

2.1. Knowledge Transfer in RL

2.2. Low Rank Embedding

3. Method

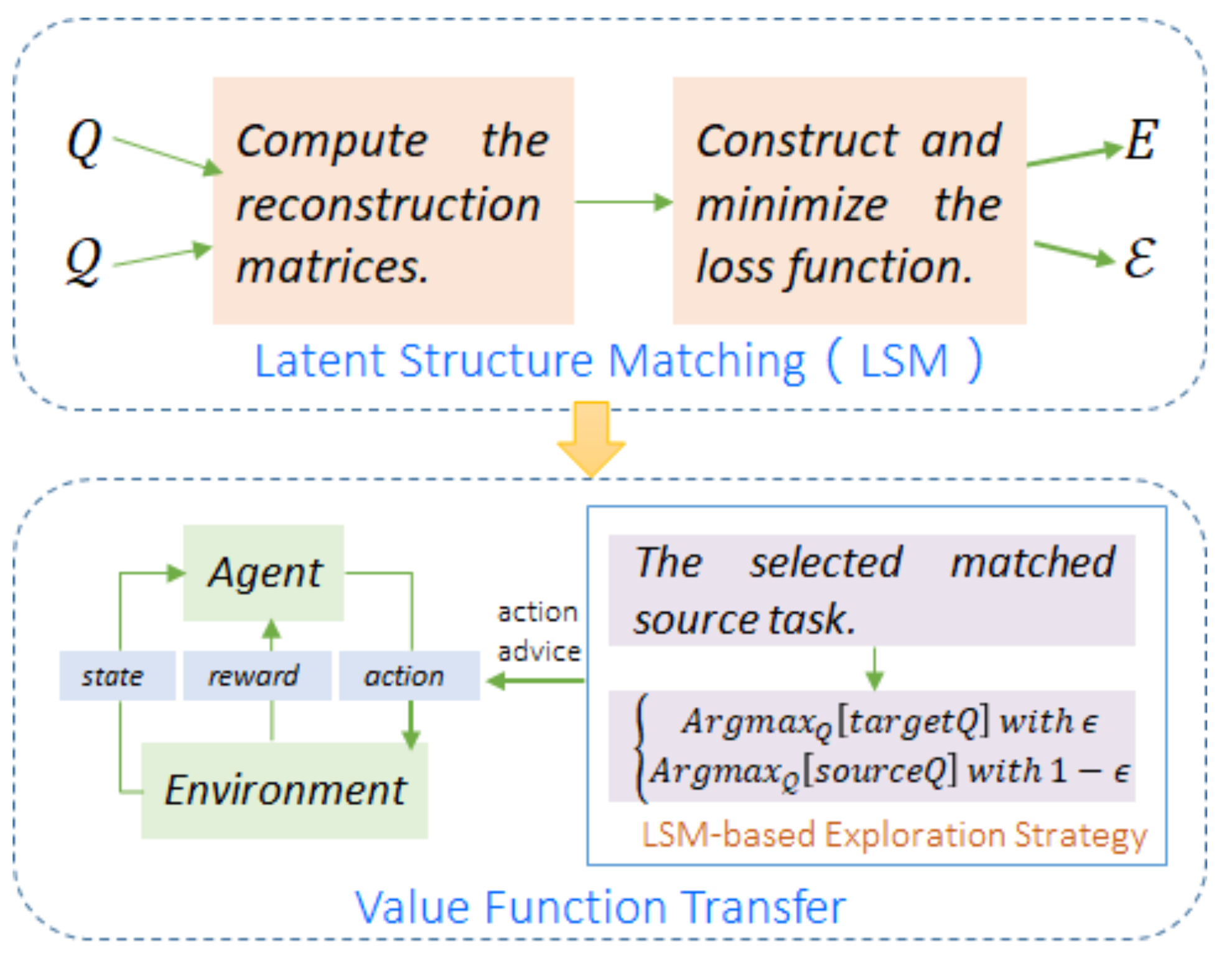

3.1. Latent Structure Matching (LSM)

| Algorithm 1 Latent structure matching |

| Input: source action value function Q; target action value function ; embedding dimension d; weight parameter Output: embedding matrix E of source task; embedding matrix of target task.

|

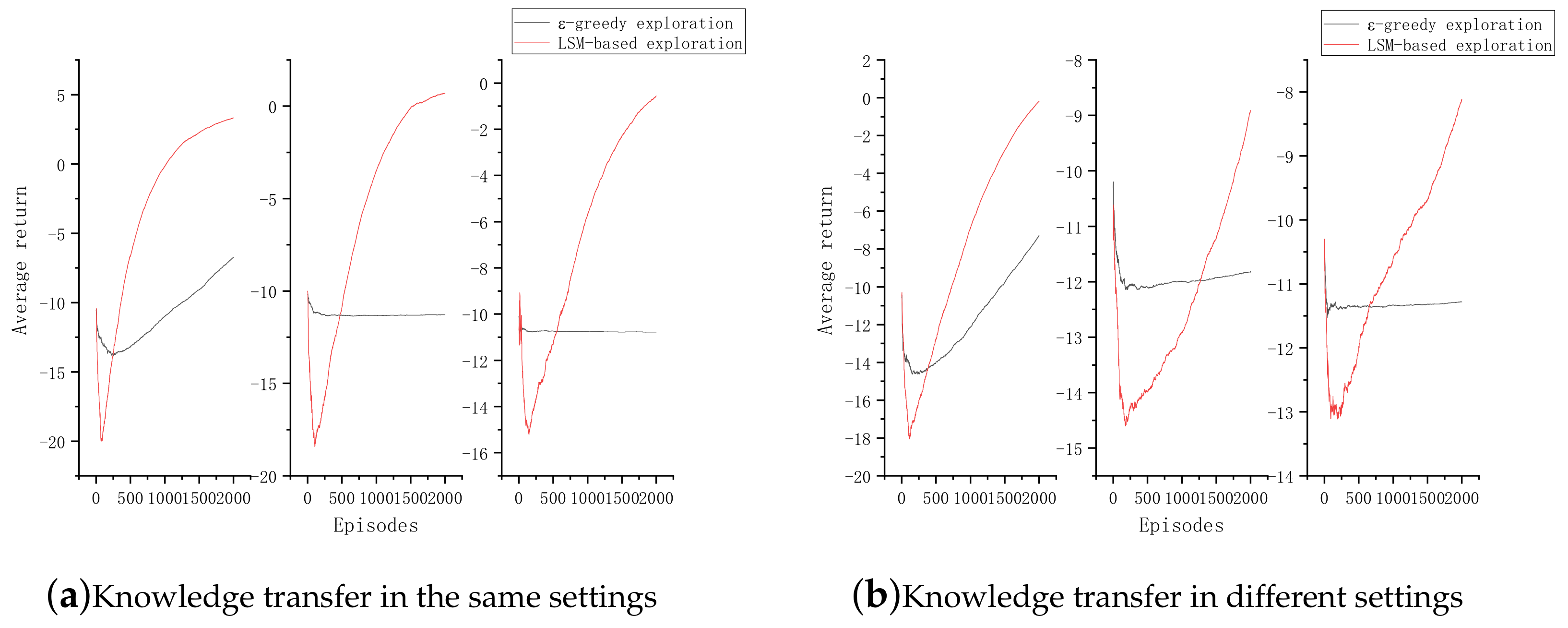

3.2. Value Function Transfer

| Algorithm 2 LSM-based exploration strategy |

| Input: ; ; Output: Action |

4. Experiments

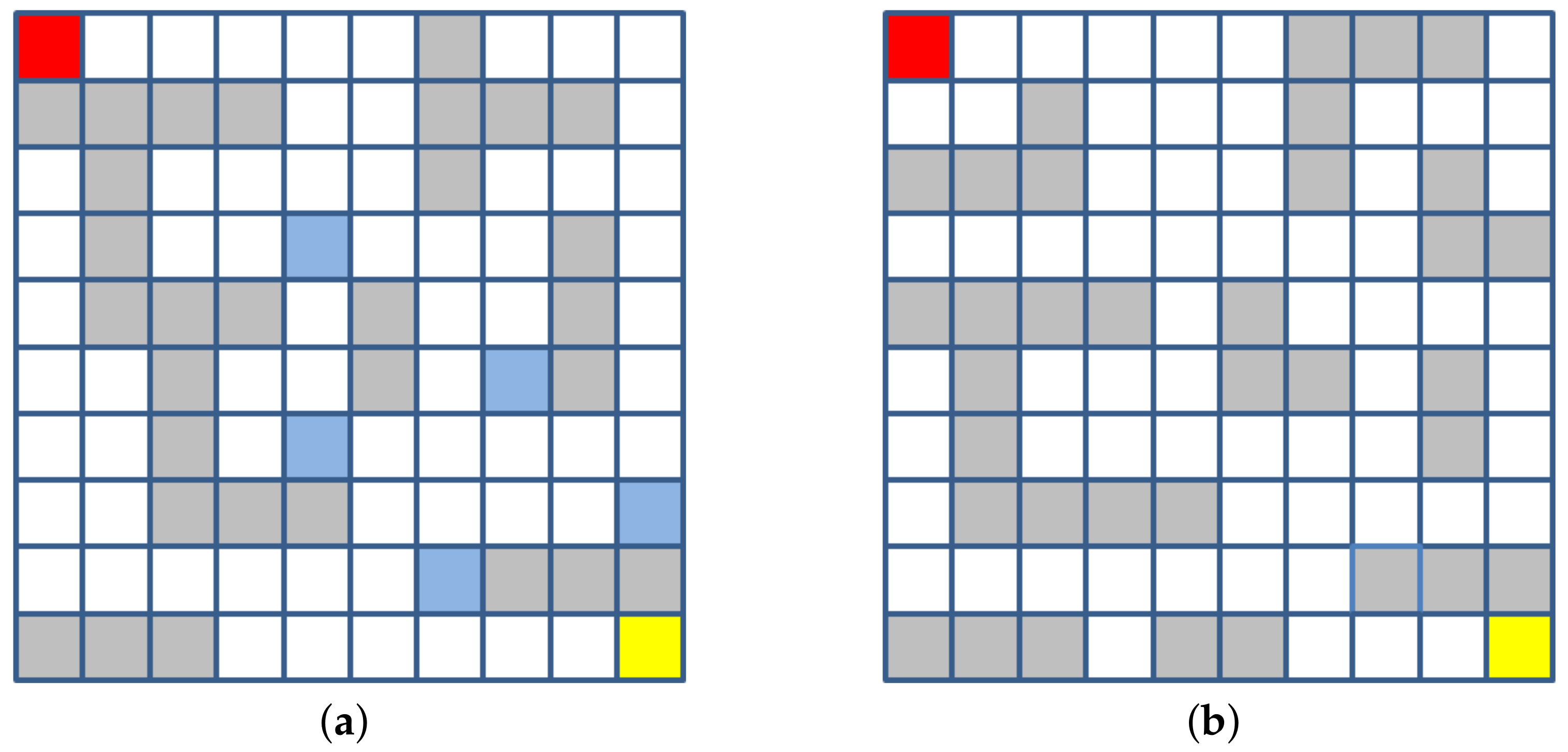

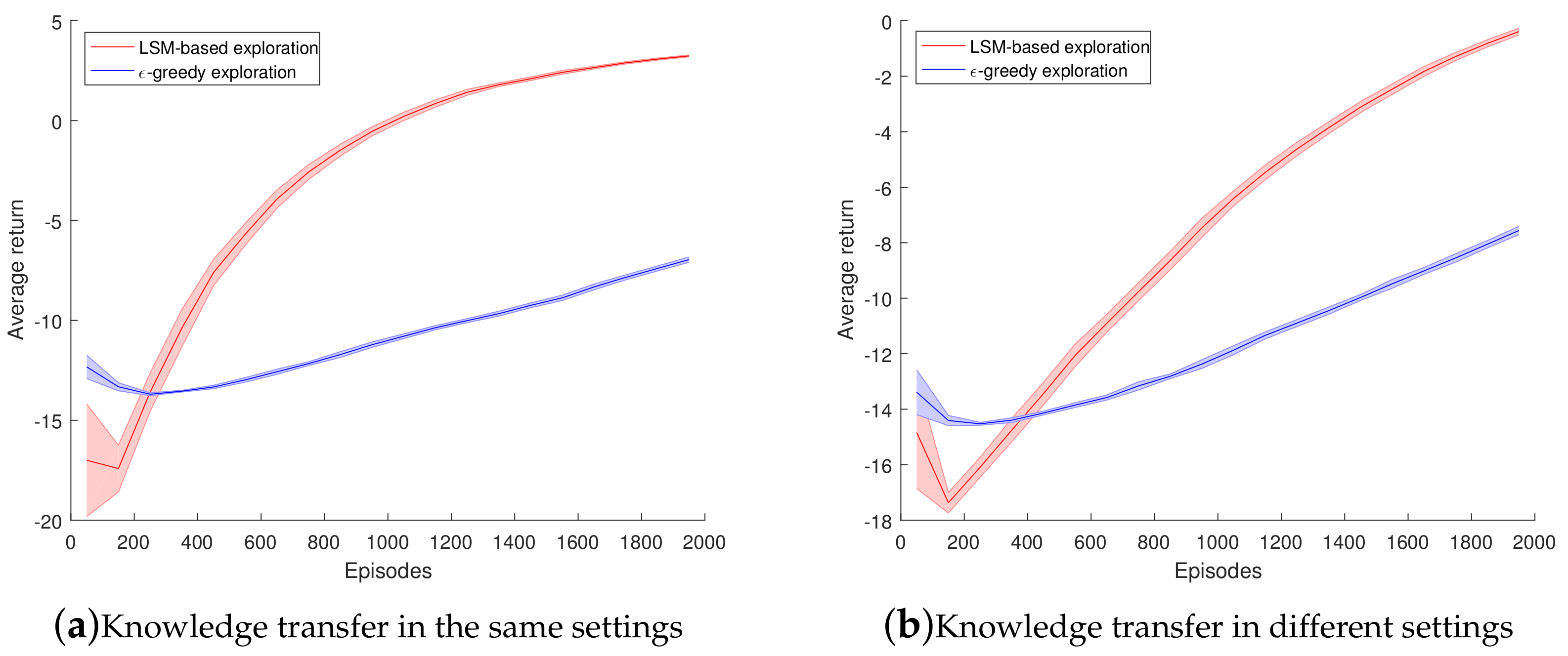

4.1. Experiments on Maze Navigation Problem

- Action: The action space is one-dimensional and discrete. The agent can perform four actions: Upward, downward, leftward, and rightward.

- State: The state space is also one-dimensional and discrete. Since each grid in the maze represents one state, there are a total of 100 states.

- Reward: When the agent reaches the target state, it will receive a reward of +10; when the agent encounters an obstacle, it will get a penalty of −10; and when the agent is in any other state, it will get a living penalty of −0.1.

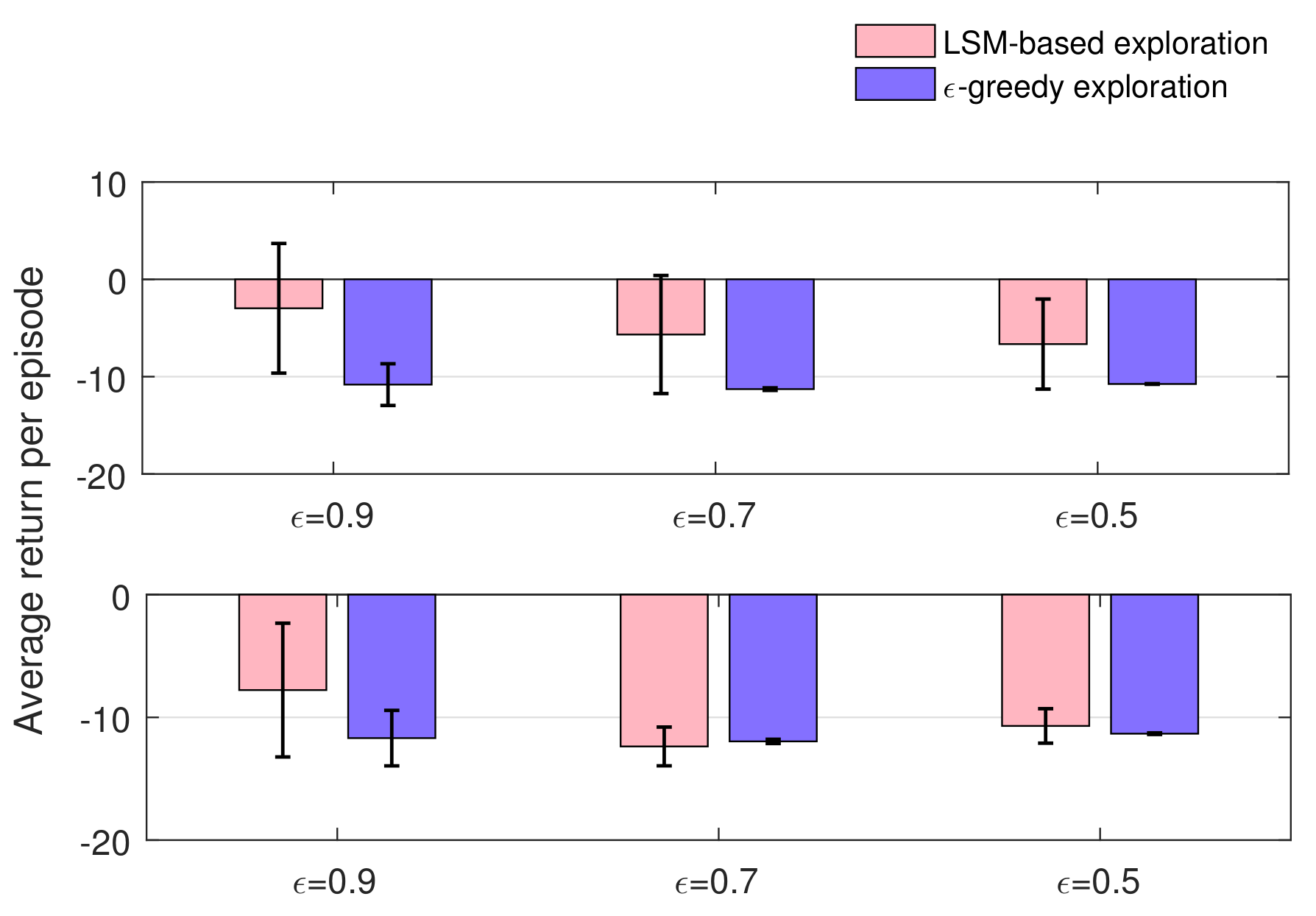

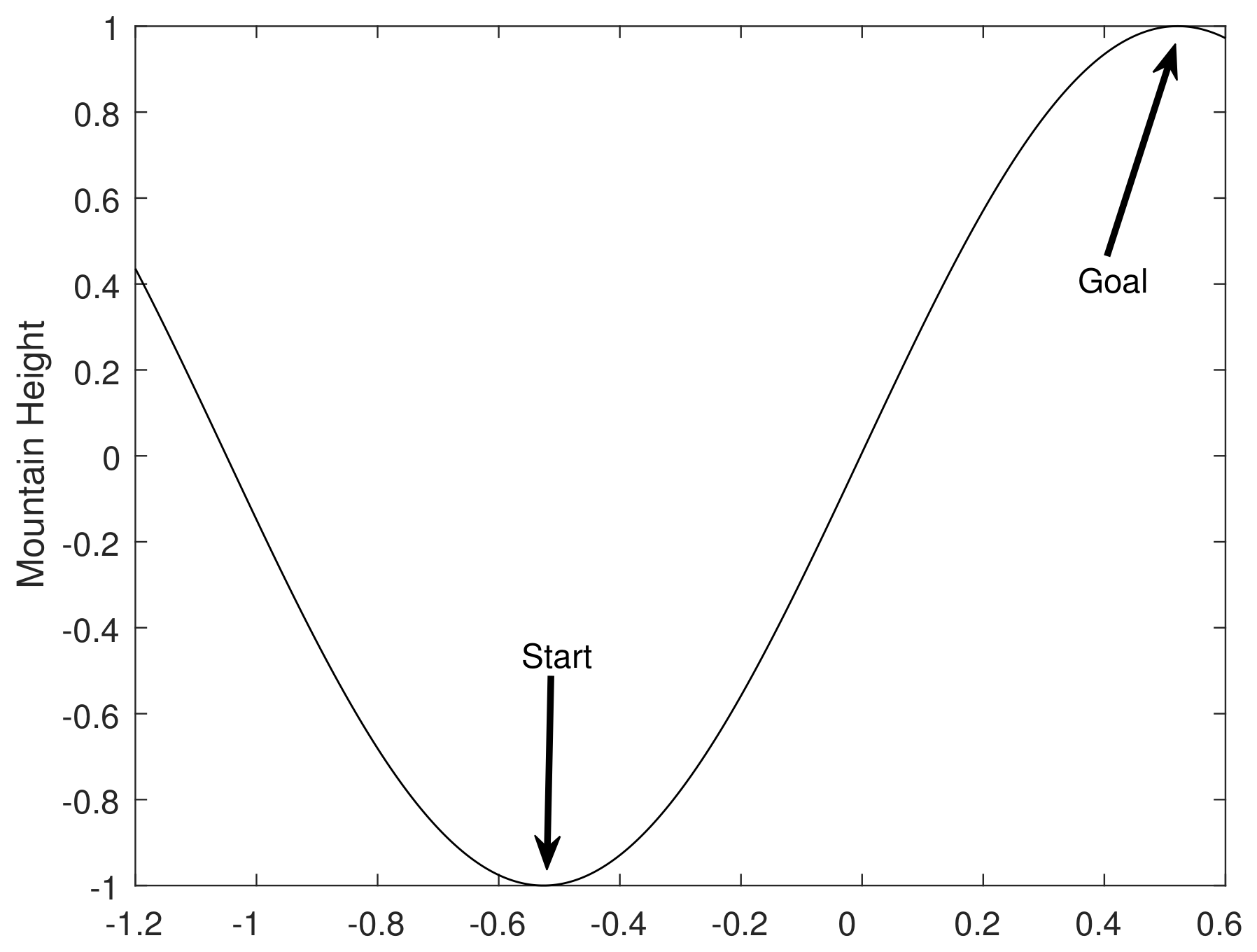

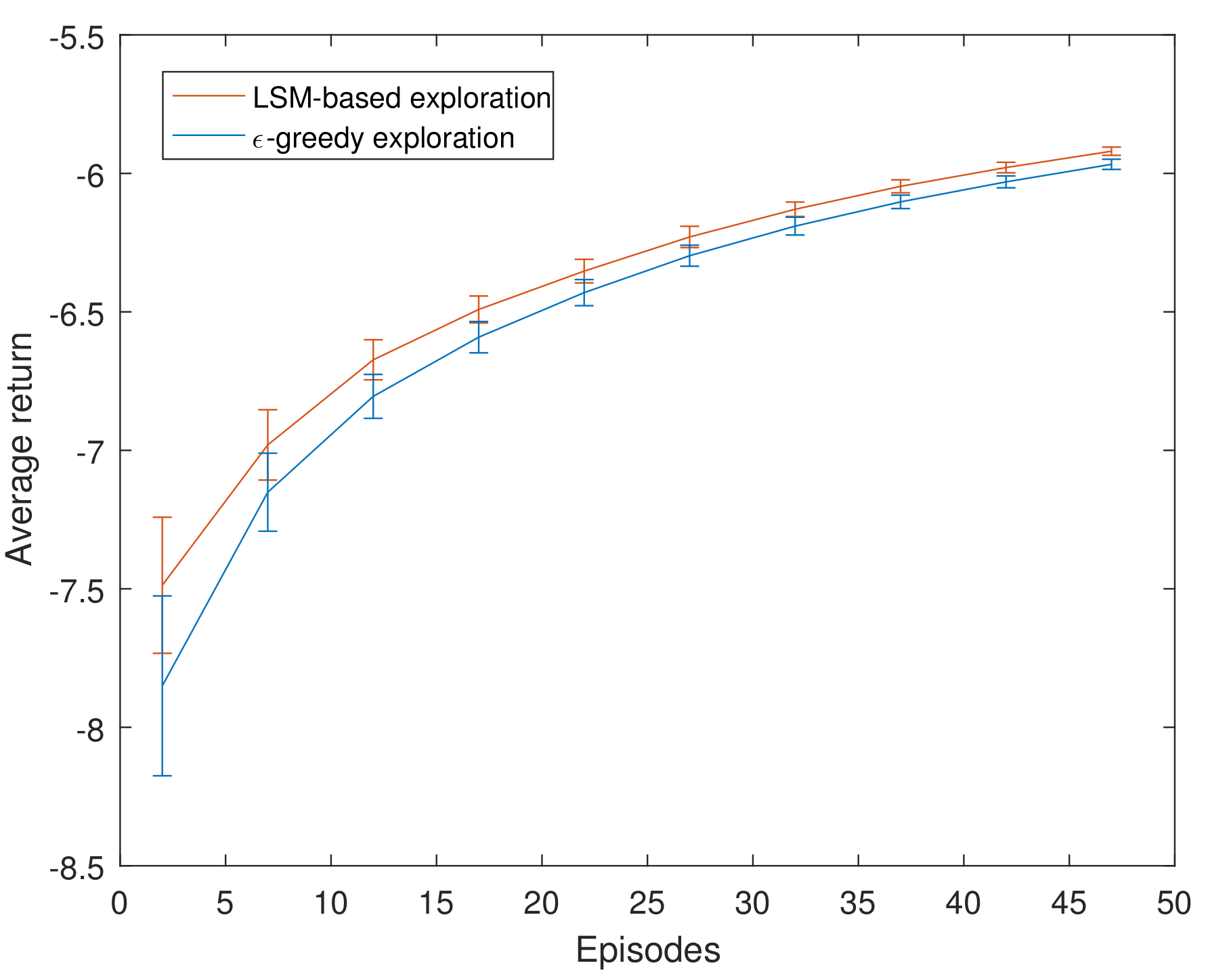

4.2. Experiments on Mountain Car Problem

- Action: The action space is one-dimensional and discrete. The car can perform three actions, including leftward, rightward, and neutral, namely:

- Reward: Each time the car arrives at a state, it obtains a reward of −1.0.

- State: The state space is two-dimensional and continuous. A state consists of speed and position, defined as:

- Initial state: The position marked "Start" in Figure 6 denotes the initial state of the car. The initial state is set as:

- Goal state: The position marked "Goal" in Figure 6 is the target state of the car. The target state is set as: .

- State update rule: A state is updated as the rule:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (a)

- for , if , it is put in the submatrix ; correspondingly, the column vector in V is put in the submatrix ;

- (b)

- if , it is put in the submatrix ; correspondingly, the column vector in V is put in the submatrix .

Appendix B

References

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1998, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reinaldo, A.C.B.; Luiz, A.C., Jr.; Paulo, E.S.; Jackson, P.M.; de Mantaras, R. Transferring knowledge as heuristics in reinforcement learning: A case-based approach. Artif. Intell. 2015, 226, 102–121. [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski, M.; Celi, L.A.; Badawi, O.; Gordon, A.C.; Faisal, A.A. The Artificial Intelligence Clinician learns optimal treatment strategies for sepsis in intensive care. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1716–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Bao, F.; Kong, Y. Deep Direct Reinforcement Learning for Financial Signal Representation and Trading. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, F.; Haziza, D.; Gomes, G. Expert Level control of Ramp Metering based on Multi-task Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 99, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, D.; Jinnai, Y.; Guo, Y.; Konidaris, G.; Littman, M.L. Policy and Value Transfer in Lifelong Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaric, A. Transfer in reinforcement learning: a framework and a survey. Reinf. Learn. 2012, 12, 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.E.; Stone, P.; Liu, Y. Transfer learning via inter-task mappings for temporal difference learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2007, 8, 2125–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Wang, X.; Shen, L. Transfer learning via linear multi-variable mapping under reinforcement learning framework. In Proceedings of the 36th Chinese Control Conference, Liaoning, China, 26–28 July 2017; pp. 8795–8799. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Wang, X.; Shen, L. An Autonomous Inter-task Mapping Learning Method via Artificial Neural Network for Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics, Macau, China, 5–8 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fachantidis, A.; Partalas, I.; Taylor, M.E.; Vlahavas, I. Transfer learning via multiple inter-task mappings. In Proceedings of the 9th European conference on Recent Advances in Reinforcement Learning, Athens, Greece, 9–11 September 2011; pp. 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Fachantidis, A.; Partalas, I.; Taylor, M.E.; Vlahavas, I. Transfer learning with probabilistic mapping selection. Adapt. Behav. 2015, 23, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferns, N.; Panangaden, P.; Precup, D. Metrics for finite Markov decision processes. In Proceedings of the 20th Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, Banff, AB, Canada, 7–11 July 2004; pp. 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.E.; Kuhlmann, G.; Stone, P. Autonomous transfer for reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Estoril, Portugal, 12–16 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Celiberto, L.A., Jr.; Matsuura, J.P.; De Mantaras, R.L.; Bianchi, R.A. Using cases as heuristics in reinforcement learning: a transfer learning application. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Menlo Park, CA, USA, 16–22 July 2011; pp. 1211–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.L.; Seppi, K. Task similarity measures for transfer in reinforcement learning task libraries. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Montreal, QC, Canada, 31 July 2005; pp. 803–808. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, T.H.; Tan, A.H.; Zurada, J.M. Self-Organizing Neural Networks Integrating Domain Knowledge and Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 26, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, H.B.; Eaton, E.; Taylor, M.E.; Mocanu, D.C.; Driessens, K.; Weiss, G.; Tuyls, K. An automated measure of mdp similarity for transfer in reinforcement learnin. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Quebec, QC, Canada, 27–31 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, H. Measuring the distance between finite Markov decision processes. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Singapore, 9–13 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K.; Murty, M.N.; Flynn, P.J. Data clustering: a review. ACM Comput. Surv. 1999, 31, 264–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liao, X.; Carin, L. Multi-task reinforcement learning in partially observable stochatic environments. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2009, 10, 1131–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Chowdhary, G.; How, J.; Carin, L. Transfer learning for reinforcement learning with dependent Dirichlet process and Gaussian process. In Proceedings of the Twenty-sixth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–8 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Karimpanal, T.G.; Bouffanais, R. Self-Organizing Maps as a Storage and Transfer Mechanism in Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.07530. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.07530 (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Taylor, M.E.; Whiteson, S.; Stone, P. ABSTRACT Transfer via InterTask Mappings in Policy Search Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 14–18 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaric, A.; Ghavamzadeh, M. Bayesian multi-task reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010; pp. 599–606. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.; Fern, A.; Tadepalli, P. Transfer learning in sequential decision problems: A hierarchical bayesian approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Unsupervised and Transfer Learning Workshop, Bellevue, WA, USA, 1–16 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Hao, R.; Su, Z. Mixture of manifolds clustering via low rank embedding. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2011, 8, 725–737. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S.; Parikh, N.; Chu, E. Distributed Optimization and Statistical Learning via the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2010, 3, 1–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candés, E.J.; Tao, T. The Power of Convex Relaxation: Near-Optimal Matrix Completion. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2010, 56, 2053–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devis, T.; Gustau, C.V.; Zhao, H.D. Kernel Manifold Alignment for Domain Adaptation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148655. [Google Scholar]

- Favaro, P.; Vidal, R.; Ravichandran, A. A closed form solution to robust subspace estimation and clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 20–25 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roweis, S.T.; Saul, L.K. Nonlinear dimensionality reduction by locally linear embedding. Science 2000, 290, 2323–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokic, M.; Gunther, P. Value-Difference Based Exploration: Adaptive Control between Epsilon-Greedy and Softmax. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Berlin, Heidelberg, 16–22 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, L.; Ding, L.; Zhang, W. Generalization Performance of Radial Basis Function Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 26, 551–564. [Google Scholar]

- Soo, C.B.; Byunghan, L.; Sungroh, Y. Biometric Authentication Using Noisy Electrocardiograms Acquired by Mobile Sensors. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C.J.C.H.; Dayan, P. Q-learning. Mach. Learn. 1992, 8, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, H.B.; Mocanu, D.C.; Taylor, M.E. Automatically mapped transfer between reinforcement learning tasks via three-way restricted boltzmann machines. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Prague, Czech Republic, 22–26 September 2013; pp. 449–464. [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov, A.A.; Makmal, A.; Briegel, H.J. Benchmarking projective simulation in navigation problems. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 64639–64648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, H.; Takeuchi, K.; Takane, Y. Singular Value Decomposition (SVD). Stat. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 64639–64648. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R. Dynamic programming. Science 1966, 8, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, A.; Dabney, W.; Munos, R.; Hunt, J.J.; Schaul, T.; Hasselt, H.V.; Silver, D. Successor features for transfer in reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 4055–4065. [Google Scholar]

| Categories of Similarity Metrics | Features | Related References |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-automatic | Depend on the experience of experts | [10,11,13,14] |

| Automatic(non-clustering-based) | Highly interpretative, but computationally expensive | [15,16,17,18,19,20,21] |

| Automatic(clustering-based) | Can tackle large number of tasks, but sensitive to noise | [23,24] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Yang, F. Latent Structure Matching for Knowledge Transfer in Reinforcement Learning. Future Internet 2020, 12, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12020036

Zhou Y, Yang F. Latent Structure Matching for Knowledge Transfer in Reinforcement Learning. Future Internet. 2020; 12(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yi, and Fenglei Yang. 2020. "Latent Structure Matching for Knowledge Transfer in Reinforcement Learning" Future Internet 12, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12020036

APA StyleZhou, Y., & Yang, F. (2020). Latent Structure Matching for Knowledge Transfer in Reinforcement Learning. Future Internet, 12(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12020036