Abstract

This paper is part of broader research entitled “Analysis of the YouTuber Phenomenon in Spain: An Exploration to Identify the Vectors of Change in the Audio-Visual Market”. My main objective was to determine the predominant audio-visual genres among the 10 most influential Spanish YouTubers in 2018. Using a quantitative extrapolation method, I extracted these data from SocialBlade, an independent website, whose main objective is to track YouTube statistics. Other secondary objectives in this research were to analyze: (1) Gender visualization, (2) the originality of these YouTube audio-visual genres with respect to others, and (3) to answer the question as to whether YouTube channels form a new audio-visual genre. I quantitatively analyzed these data to determine how these genres are influenced by the presence of polymediation as an integrated communicative environment working in relational terms with other media. My conclusion is that we can talk about a new audio-visual genre. When connected with polymediation, this may present an opportunity that has not yet been fully exploited by successful Spanish YouTubers.

1. Introduction

The research on YouTubers, as a recent sociocultural and technological phenomenon, does not have a long tradition. This was the main reason for developing this research, which should be urgently completed because YouTube is a phenomenon that is decisively influencing contemporary audiovisual consumption and causing a series of dysfunctions in understanding audiovisual processing, production, distribution, and consumption. These dysfunctions are not necessarily negative, but I propose some ideas for more fluid short-term development. To do this, I propose a simple hybrid (quantitative and qualitative) analysis method, in addition to applying a theory of audiovisual media called polymediation.

In this paper, I present research that emerged from the research group to which I belong, INFOCENT (Información, Ocio y Entretenimiento/Information, Leisure, and Entertainment), at the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Madrid, Spain), that has been underway since 2017. This report is part of a research project entitled “Analysis of the YouTubers Phenomenon in Spain: An Exploration to Identify the Vectors of Change in the Audio-Visual Market”, directed by the principal investigator, Álvarez Monzoncillo. In this research, we propose a methodology to analyze how the YouTuber phenomenon might be a new audio-visual paradigm that sheds some light on the tendency of audio-visual entertainment in the coming decades. The emergence of content creators on YouTube, whose profit is related to the number of views of their content and the new audiences that are migrating from classic media, is revolutionizing the viewing of audio-visual content on the Internet. YouTube is generating a new market formed by a worker-producer that generates content, an audience or public in some cases with interactive behavior (prosumers), advertisers who buy the advertising spaces of various formats on these channels, and a monetary flow related to this advertising. In INFOCENT, we analyzed this phenomenon through several work scenarios, some indications of research, and a methodology to address the subject, using mixed and transversal techniques that combine qualitative and quantitative research.

The main hypothesis (H1) that we address is that the consumption, creation, and distribution of audio-visual content generated by users (UGC or user-generated content) on the Internet, mainly on YouTube—popularly known as “YouTubers”—will not substantially change the context of the consumption, creation, and distribution of audio-visual content of the traditional broadcasters or OTT services in the short term. OTT or over-the-top refers to the delivery of audiovisual content streamed over the Internet without the involvement of an Internet service provider (ISP) in the control or distribution of the content. The ISP is neither responsible for, nor is able to control, the viewing abilities, copyrights, and/or other redistribution of the content, which arrives from a third party and is delivered to an end-user’s device” [1].

Within this methodological framework, my paper is an original individual proposal, which is framed within the aforementioned research, that I have completed individually. My research shows a synchronous cut on a specific date: 5 May 2018. From this cut, I obtained a data packet extrapolated from SocialBlade, a proven tracking website of some relevant social networks. I explain this further in the method section.

In INFOCENT, we obtained clues as to how many aspects are changing in the traditional audio-visual consumption model: Generation of a community in permanent connection, new aesthetics and genres, new business models, increase in social disaggregation, nomadic and multiscreen consumption, omnivorous consumers, etc. These characteristics led me to use a theoretical concept—genuinely used in my own research—that, although recent, collects these in addition to providing additional theoretical value: Polymediation. This concept is related to the second hypothesis (H2) that we investigate: We think that the main YouTuber motivation is not the need, but the opportunity to provide content. So, the key factors of YouTuber success would be substantially different from the traditional factors: YouTubers focus on sharing a personal experience, creating a special audio-visual process, and building a trade name authorship, using for this any appropriations strategy, parody, pastiche, etc., which are factors related to polymediation.

This opportunity, given the need, is related to a certain narcissism or egocentrism present in social networks. Elsewhere, I analyzed the type of representation model that gives rise to this basic feature of the relationship of users (creators and consumers) with YouTube and other similar media [2]. As Ksinan and Vazsonyi claimed, there is a lack of consensus about how narcissistic Internet use impacts social relations, but this result could be due to the lack of differentiation between two distinct types of narcissism: A grandiose type and a vulnerable type, which function differently “with Internet behaviors and social outcomes”. In their research, they concluded that:

The links between narcissism and social anxiety/social self-efficacy were partially mediated by preference for online social interactions (POSI); however, the two types of narcissism show distinct links to the two outcomes. Vulnerable narcissism was positively associated with POSI, which indirectly predicted problems for both measures of social relations; in contrast, grandiose narcissism was only directly and positively associated with social self-efficacy and negatively with social anxiety [3].

Here, I clarify that some of the success cases that I have recorded are categorized into this type of grandiose narcissism, whereas in other cases, this categorization is more problematic. All these successful YouTubers make this narcissistic exhibition a business by means of the monetization allowed on the YouTube platform. In this sense, this kind of business existed already in the origins of YouTube, with audio-visual characteristics originating in the prosumer, as can be deduced from this statement from one of YouTube’s co-founders, Jawed Karim: “It was the first time that someone had designed a website where anyone could upload content that everyone else could view” [4] (p. 22).

Related to narcissism, but analyzing Youtubers from what Cocker and Cronin called the new cult of personality, they “differ from their traditional counterparts through collaborative, co-constructive, and communal interdependence between culted [sic] figure and follower”, to the point that in Youtube, “the ‘culting’ [sic] of social actors becomes a participatory venture” [5]. Again, polymediation would be the key to shedding new light on the YouTuber phenomenon. This analysis could be applied to some of the success stories that I found in my sample, as the most famous in the Spanish case: elRubius. One of the keys can be found here: The emergence of many current YouTubers. As alleged by Levy, “it is no longer enough to have the American dream of fame and fortune ephemerally available to everyone—people want it on their desktops and on their cell phones” [4] (p. 167). Therefore, this narcissism, from the consumer side, would also be one of the YouTuber phenomenon success keys. Narcissism was analyzed in the same line by Ashman et al. [6] when they claimed that YouTubers “encourage a self-centered subjectivity where individuals pursue their own self-interest by seeking popularity at all costs” (p. 482).

Beyond this relative narcissism, but still related, other authors, such as Lange [7], discussed YouTube as a provider of videos of affinity, understood as all kinds of feelings of connection among the users (p. 73). It does not mean necessarily generalist videos—none of the success stories I found can be classified as such—but a "selection of audience" (p. 74). While for traditional television this would be problematic in success terms of translatable monetization, in this case, success is drawn from the wide audience, if one considers the diffusion of Spanish language in the world as virtually more than 477 million people speak Spanish as a native language, the second in the World after Mandarin Chinese, in 31 different countries, and 572 million Spanish speakers as a first or second language—including speakers with limited competence—and more than 21 million students of Spanish as a foreign language [8]. Also by the easy access, both by the interface and by not being conditioned by television programming. YouTube is also available indefinitely. One of the successful genres I have found that focused on video game commentary, or gameplay, is originally from the Internet era, and is related to this feeling of affinity. As Lindley stated, in gameplay, the YouTuber explains how they interact with video games, its rules, and how to challenge and overcome the games [9] (p. 183).

However, other authors, such as Ashman et al. and Berlant [10], balanced what is perhaps a too optimistic or naïve vision of the YouTuber world, as previous studies have not addressed the “three main wellsprings: The dynamics of competition, the creativity dispositif [sic], and technologies of the self” that “detrimentally affect the quality of their lives and collectively institute a ‘cruel optimism’ which promises much but delivers little” [6] (p. 1). This cruelty refers to the fact that YouTubers’ work “links so tightly to their self-esteem—since it derives from doing something they deeply desire—yet the gains evidently manifest quite precariously” [6] (p. 482). I would say this is the case for most of the samples that I have examined in my research. In this sense, as I will show at the end of the analysis, and as Hess claims in a more political sense:

The structural limitations of the medium of YouTube and the overwhelming use of YouTube for entertainment diminish the response. Ultimately, YouTube’s dismissive and playful atmosphere does not prove to be a viable location for democratic deliberation about serious political issues.[11]

I have noted above how YouTubers’ audio-visual production differs from traditional production. The most obvious difference is its distribution, as in this case, through a channel posted on YouTube. Even though several of the case studies that I review would seem to be amateur productions, they have millions of views. The democratization (lowering) of the media is not only shown in the production (video recording), but, above all, in the distribution level, because, as Bell et al. noted, “the mechanics and architecture of platforms, such as YouTube and Facebook, have provided a rich breeding ground for these types of cheaply produced content” [12]. In that sense, I agree with Burgess and Green [13] when they say that “the distinction between market and non-market culture is unhelpful to a meaningful or detailed analysis of YouTube as a site of participatory culture”, as it is a platform with low entry barriers as YouTube provides a structure for what has always been the most complex, remote, and expensive custom of access for amateur production: Distribution and exhibition (p. 103). Thus, with the lowering of production costs, success only depends on the YouTuber knowledge, participation in the YouTube ecosystem, the savvy with which they produce content, and their mastery of YouTube’s homegrown forms and practices (p. 104).

Duffy united both perspectives that I have been handling, one more psychological in its narcissistic conclusion and another more entrepreneurial, like the one I have just described. Duffy discussed neoliberal ethics and its implications, with a special interest in the case of entrepreneurial women—although they have a low presence in my body of work. Duffy draws attention to the gap among those who find lucrative careers and the rest, maybe dreamers, whose “passion projects” amount to free work for corporate brands as they:

were motivated by the wider culture’s siren call to get paid to do what you love. But what they experienced often fell short of the promise: Only a few young women rise above the din to achieve major success. The rest are un(der)-paid, remunerated with deferred promises of ‘exposure’ or ‘visibility’.[14]

In the terms that I apply, this could be expressed as: Work to feed your ego—and maybe you will be monetized the remaining effort from that value. Duffy stated that “through the framework of aspirational labor, these women come to resemble the traditional media workers […] they have defined themselves against [and finally] reaffirming the already-tight bond between consumption and femininity” [14].

These ideas were also reported by McRobie who analyzed the same dilemma as Duffy, also with a feminist perspective, but using professionally, Berzosa thinks about it as subjects focused on activities that were part of the public sector in the past (children, elderly, and the vulnerable caring). Finally, McRobie launched a question that, after analyzing the cases of successful Spanish YouTubers, is addressed in my conclusions as a sociopolitical reflection: Are the YouTubers and similar practices of creative labor able “to mobilize a new radical voice”? [15].

Beyond the feminist approaches in a medium as young as YouTube, one cannot lose sight of the fact that, as pointed out by Burgess and Green from cultural studies, YouTube is a media of “participatory culture”, but the implications must be taken seriously because YouTube is considered to be their “core business” [16]. The idea was not originally introduced by them as Jenkins had already spoken earlier about this kind of participatory culture when he stated that:

Circulation of media content—across different media systems, competing media economies, and national borders—depends heavily on consumers’ active participation […] a cultural shift as consumers are encouraged to seek out new information and make connections among dispersed media content.[17]

Despite this, Burgess and Green pointed to political contradictions and commercial culture mediation, born of an environment whose diversity in multi-platform digital distribution makes it difficult to call YouTube just “the mainstream media”.

In the Ibero-American area, researchers, like Sabich and Steinberg [18], followed the same line as Burgess and Green and Jenkins, stating that:

The enunciation mechanisms typical of the YouTuber discursivity build a narrative structure that tends to professionalization, a form of multidirectional appearance of contemporary subjectivities and a specific logic of intervention, socialization and interaction in the Internet (p. 1).

What has already become popular both in academia and among YouTubers is the use of the concept of “communities” instead of a “social network”, which has fallen into disuse for these cases of YouTube channels [19]. From this same perspective, Elorriaga and Monge [20] focused on the influencers of YouTubers subgenre, analyzing how there are some YouTubers, even starting from amateur positions, that have managed to shape communities and have necessitated "brands to re-invent their communication to keep connecting with their consumers". This is the case, for example, of the YouTuber, Verdeliss, a 33-year-old mother of several children who was successful among the Spanish YouTubers at the end of 2018.

This ability of the influencer YouTubers, as indicated by Pérez-Torres et al. [21], reminds us that, beyond the negative impact that I have pointed out above, the YouTuber universe is perhaps one of the most decisive for the creation of codes related to the construction of adolescent identity. As they specified, “most of the messages relating to personal identity were aimed at transmitting the self-impression of the YouTuber and the relationship of that self-impression with his gender identity, sexual orientation, and vocational identity […]” (p. 1). Teen followers interact with YouTubers as one more expression of the fan phenomenon, adding to it by telling their personal stories. So, to understand the development of personality during adolescence—which is one of the age sectors that most interacts with YouTube—it is necessary to conduct further research into that interrelation. In this sense, “YouTubers are perceived by young people as their peers, but also with qualities (creativity or talent) that they often admire” (p. 69).

Ramos-Serrano and Herrero-Díz [22] delved into the influence aspect not as a subgenre, but as a basic characteristic of the successful YouTubers because they create opinion, and this makes them attractive to companies and the industry. They concluded “the key of [a YouTuber] success is the community of followers and that is why his future will depend on his ability to keep the balance between his specialization and the commercial content” (p. 115).

From an initial approach similar to mine, Scolari and Fraticelli [23] analyzed the production of the quantitative data collect from the top 10 Spanish YouTubers. They textually analyzed the five top videos of each of these YouTubers. I share one of their research questions: “What genres can be identified in the top Spanish YouTubers’ production?” (p. 1). The date of the sample was 2 July 2015, so it will be interesting to see if some evolution in the audio-visual genres that they located has occurred. I only anticipate that two of the top 10 Youtuber channels are still listed in 2018–2019: ElrubiusOMG and vegetta777 (p. 11), which highlights the fierce competition in this type of entertainment channel. Besides, certain kinds of YouTuber audio-visual production are related to aesthetics and content “to satisfy the desires of a new generation of viewers formed in hypertextual experience” (p. 7). This brings us back to the concept of polymediation, which can be related to a concept that Scolari reflects on: Hypertelevision is something that shows screen fragmentation, acceleration of rhythm, intertextuality, rupture of narrative linearity, and multiplication of characters and narrative programs, comparing, then, the “old” and “new media” [24]. From this point, I diverge from Scolari and Fraticelli’s analysis because I think that, beyond dealing with audio-visual products, the current media models are already radically different. One cannot talk about the evolution or adaptation of traditional media as these top YouTubers are new players in the future of the Internet. I agree when researchers claim that YouTubers, beyond uploading videos—virtually continuously, as a kind of horror vacui—do not just “create their individuality through those videos. Therefore, YouTubers should also be considered as ‘media subjects’” [23,24] (p. 5, p. 8). This is another aspect in connection with the polymediation.

To summarize this literature review, since the emergence of YouTube in 2005, the academic literature has not stopped growing due to both its economic and sociocultural implications. In my analysis, I mix both perspectives focused on successful Spanish YouTubers. Several concepts are repeated, including narcissism, personality cult, affinity, and others unrelated to the technology itself: The business world and political freedom. There is also a sense of mantra, which is related to one of the concepts that I used in the title: Success. Berzosa thinks about it as if:

The successful YouTubers seem to share an element of truth and trust that makes them able to drag huge numbers of followers. A successful model from the point of view of the diffusion of the content, crucial for the creator to see satisfied their concern to impact in the audience, and also factor of enormous interest for the brands that follow closely this industry that, for some time now, struggles to produce formats with which to reach consumers better, in the age of storytelling, to tell stories to connect better with users, as well as to look for prescribers, influential profiles, with dragging capacity [25].

In my analysis, I show how most of this success is distributed equally among YouTubers that are basically dedicated to three audio-visual genres: Gameplay, reviews (specialized in certain subjects, especially for children), and fiction (short pieces of animations, miniseries, and memes). In this sense, I perceived a trend in the studies on YouTubers, especially in the first two genres and related to the participatory culture that I relate directly to the concept of polymediation.

2. Methodology

The method of analysis used in this paper is a hybrid between quantitative data directly collected from the YouTube platform, as well as from SocialBlade, a website of data gathering and visualization not only dedicated to YouTube, but to all kinds of social networks, like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, and a more qualitative approach in which I analyzed these data in response to a broad vision of the YouTuber phenomenon. I applied a synchronous cut on a specific day in 2018.

The body of work is composed of the 10 most successful YouTubers in Spain. The criterion of membership in this ranking includes the number of visualizations and subscribers to each channel, as well as the SB criterion from SocialBlade [26]. When this web was created, they just listed rankings based on the number of subscribers and the number of views, but it quickly became evident that this was not an accurate indicator of how people were actually doing on YouTube. Someone could have a bazillion subscribers that they cheated to get without having any actual views. The SB ranking system aims to measure a channel’s influence based on a variety of metrics, including the average view counts and the amount of “other channel” widgets listed. If you have an A+, A, or A- SB rank, then you can consider yourself very influential on YouTube. This SB criterion is not totally accurate from a methodological point of view, but it can be integrated with some qualitative aspects that were of interest to me. In the analysis in Section 3, I expand on this idea and I propose some supplementary qualitative criteria.

Considering this ranking, the next step was to classify the members by audiovisual genres as well as by the age of the users to which these channels were aimed. In addition, I attempted to relate all this to the Spanish sociocultural context and examined, from a more sociological point of view, the possible deviations in the age ranges that could exist in the consumers of these channels.

Finally, after drawing this map, I related it to the concept of polymediation, which I explain in the next section. The map helped me to open up the qualitative research to propose new avenues of investigation that can help other studies related to YouTubers channels, as well as to their protagonists and users themselves in order to improve any aspect of this type of audiovisual structure.

Polymediation

Polymediation, as established by Madianou and Miller, is “an emerging environment of communicative opportunities that functions as an ‘integrated structure’ within which each individual medium is defined in relational terms in the context of all other media” [27]. In this sense, YouTube and the channels created by YouTubers are clear examples of polymediation, at least as far as its most basic structure is concerned.

From this perspective, Calka posed a question about how the media, identity, and our performance are related to an iconic saturated ecosystem. His research framed polymediation as a “discursive point of articulation for exploring the processes and outcomes of media convergence and fragmentation”. That is, polymediation is a transition from thinking about the media as something one only consumes as one more product to understanding it as a process of which one has adopted. I think it is interesting to analyze this type of adaptation in the audio-visual genres. Calka sees it as:

An opportunity for connection, invention, re-invention, and community, for bolstering and verifying aspects of our identity or playing with new possibilities for what one might become. The complex relationship among media, identity, and performance is necessarily in flux. As our technological landscape changes, so will our identities and relationship to media.[28] (pp. 27–28)

Calka distinguished different levels of polymediation, which can best be treated under five key aspects [28] (p. 15–26):

- (1)

- Ubiquity: Widespread and simultaneous accessibility and presence of media. From this, there are saturation phenomena of media platforms in our daily lives, the alteration in how information is sought, and how people connect with others and maintain relationships, while also providing many opportunities for distraction.

- (2)

- Shape-shifting authorship: Multi-author mediation of messages in different contexts referring to the increasing power individual users must have in creating and distributing content; so, they are simultaneously consumers and producers.

- (3)

- Simultaneous fragmentation and paradoxical merging or unifying performance of identity: A paradoxical fragmented/unified presentation, as users’ presences online are all a part of who they are. These presences are performed specifically for others and are simultaneously fragmented as not everyone sees all these performances as they are intended for different audiences.

- (4)

- Division and communality: Paradoxically, community is an extension of personal identity performance, but fragmentation does not prevent the possibility of communality, sometimes allowing us as individuals to engage with more communities that users might not otherwise be able to access without the technology.

Other authors, such as Madinou and Miller, understand polymedia as a new theory that can be used to understand the consequences of using digital media in the context of interpersonal communication [28] (p. 170). They understand a polymedia environment as an increasing number of communications technologies across different platforms that are used simultaneously or to complement one another. User identities across online platforms may be broadly similar or may shift in emphasis, from professional to social identity and among media. So, “the poly-media environment requires an individual’s identity to perform different functions in a digital networked world” [29] (p. 25). However, it can happen as a communicative environment of affordances, not as a technologies catalogue. Thus, the primary concern of polymedia is to avoid the technological limitations and move toward the social interactions field, focusing on the emotional and ethical consequences. The reason for this is that each medium, with its different communicative possibilities, is deeply linked to the ways in which interpersonal communication through technology are experienced and managed. Some of those ways enabled by polymedia are “ultimately about a new relationship between the social and the technological, rather than merely a shift in the technology itself” [27] (p. 170). Madianou and Miller’s main argument was that polymedia is about “a new set of social relations of technology, rather than merely a technological development of increased convergence” (p. 171). To understand this, they distinguished three preconditions: (1) Access and availability, (2) affordability, and (3) media literacy (p. 171). Polymedia is not just the environment, but is also how users relate to and develop these affordances, and how their emotions and their relationships flow (p. 172). Madianou and Miller posited that this flow or negotiation “often becomes the message itself” (p. 173). This means that it is not only about multimedia or media ecology, but is also polymediation of how the entire environment of different media affects or mediates between the media and the users.

Baym deepened the understanding of polymediation, highlighting seven key parameters: Kinds of interactivity, temporal structure, social cues, storage, replicability, reach, and mobility. Baym employed these key concepts to consider different facets of human communication, including the degree to which media is viewed as more or less authentic compared with face-to-face interaction; the sense of community, identity, gender, veracity, and the self; and how such factors work in various forms of highly personal or impersonal contexts for communication and the creation and maintenance of relationships [30].

Madinou et al. summarized polymedia as a transformation in technology and how users interact with it. People, traditionally limited to a couple of forms of media for communication, now have access to different media. However, the importance is not the number, but the new affordances and ways of using that offer temporality, storage capacity, reproducibility, materiality, mobility, and reach [27] (p. 183). There is a sense of re-socialization in media democracy and literacy, as users choose a medium as a shared social act. This is related to theories about mediation [29,31] or mediatization [32,33,34], which reflects the mutual shaping of social processes and the media and how to encompass the changes caused by the media into every aspect of our lives.

The concept of mediatization has its origins in the notion of replication, “the spreading of media forms to spaces of contemporary life that are required to be represented through media forms” [32] (p. 5). Both concepts come from the same theoretical background, but differ in application. Mediatization denotes the processes through which core elements of cultural or social activities assume media form. Therefore, those activities are relatively performed “through interaction with a medium, and the symbolic content and the structure of the social and cultural activities are influenced by media environments which they gradually become more dependent upon” [35] (p. 105). Mediatization highlights the independence of the media “with a logic of its own that other social institutions have to accommodate to”. Simultaneously, these media “become an integrated part of other institutions” (id.). Mediatization also describes the transformation of many disparate social and cultural processes into forms or formats suitable for media representation [32] (p. 7). This (poly)mediatization is perhaps contradictory to the theories of globalization that hypothesize a flat world [36], as this cannot be alien to the peculiarities of each society. First, being a phenomenon that is already hugely popular, mediatization is far from reaching a significant level among the total potential users, at least in Spain. To discuss this unlikely globalization serves as an example in the cases of the Spanish Youtubers that I have chosen. I then wanted to examine how polymediation manifests itself in the Spanish case. For this, I analyzed the 10 most influential YouTubers using metrics from both YouTube and the qualitative data from SocialBlade.

3. Results

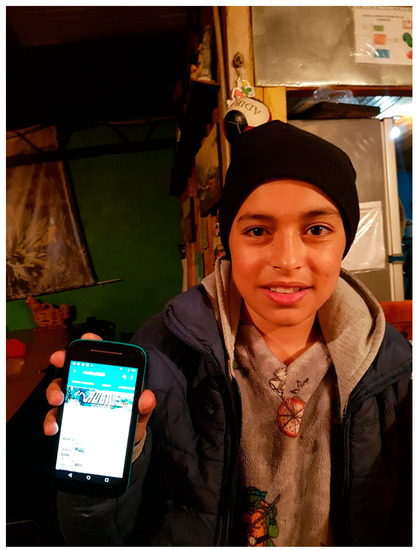

In 2016, I had the opportunity to visit Colombia to shoot a documentary in a mountainous area. In general, the landscapes and the people impacted me, but my most memorable moment was when, in a village with just one street, I met an eight-year-old boy interacting with his mobile phone. I was blown away by the discovery that he was a follower of elRubius, the popular Spanish Youtuber (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Colombian child using elRubius’ YouTube channel, one of the most popular in Ibero-American countries. San José de Sumapaz (Colombia). © the author 2016.

The main objective of my analysis was to show the predominant audio-visual genres among the 10 most influential YouTubers whose content creation is completed in Spain. This top-10 ranking is extrapolated from a statistics website called SocialBlade.com, an independent website, whose main functions are to track social networks and offer statistics across multiple social media platforms. They are a leading provider of social media statistics that are freely available to anyone using their website. SocialBlade.com offers three different rankings about the most successful Youtuber channels worldwide, and by country: (1) Subscriber numbers, (2) video views, and (3) SB rank.

The SB ranking is provided because rankings based on subscriber numbers and number of views are not always an accurate indicator of what people are doing on YouTube. For example, a YouTuber can have many subscribers that can be fraudulently obtained without having any actual views. So, with the SB ranking system, you can discriminate these fake accounts, and measure a channel’s influence based on various metrics. SB only assigns a channel an A++, A+, or A rank if it is influential.

This is a quantitative approach, but one that helped me to complete a qualitative final analysis. For this, I used the concept of polymediation that I described above. Polymediation is a term that refers to the numerous types of technology that users try and to the multiple ways in which they interact with technology. This summarizes the qualitative objective of my analysis, since YouTubers shape a kind of channel that is based on the fusion of different media and, above all, proposes a new form of interaction with users. From this perspective, my hypothesis is that YouTubers act as mediators between (poly)media convergence and users. I then examined how polymediation manifests itself in the Spanish case. For this, I analyzed the top 10 most influential YouTubers by combining SocialBlade’s two quantitative metrics with their more qualitative metric.

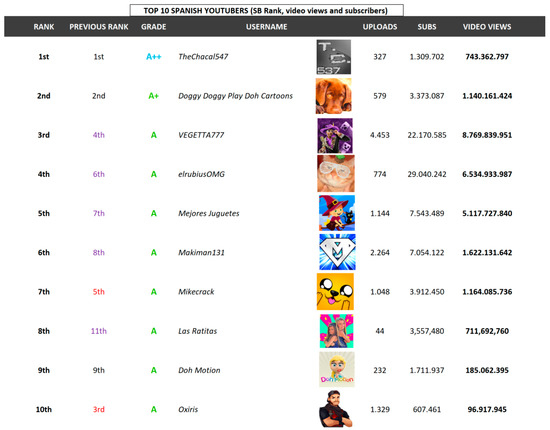

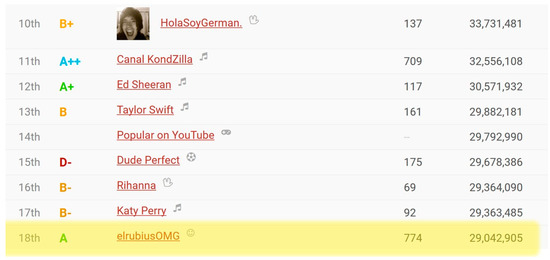

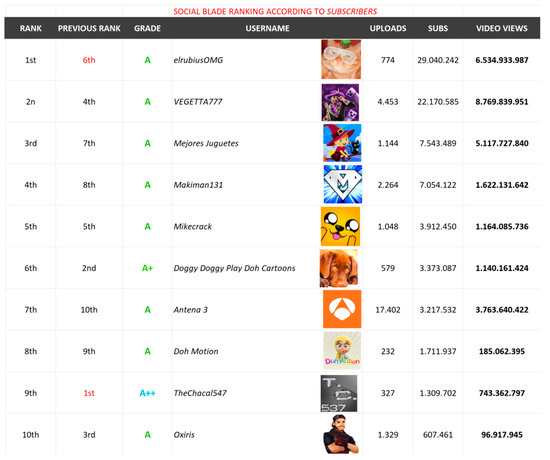

The 10 top YouTubers in Spain sorted by the SB ranking are shown in Figure 2 [26].

Figure 2.

Top 10 Spanish YouTubers sorted by SB Rank.

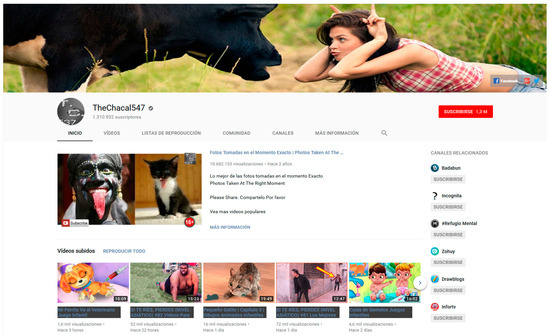

Only one of the current Spanish YouTubers achieves a blue A++, TheChacal547 [37], who created his channel in 2014 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Front page of the YouTube channel, TheChacal547.

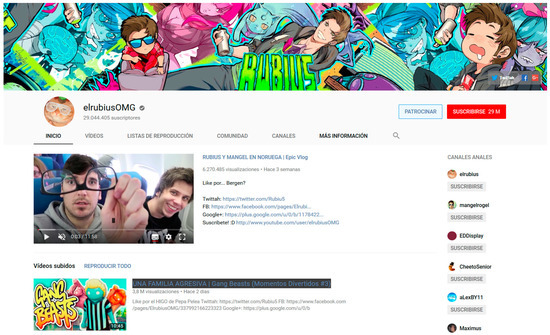

The only description of this channel is that it “provides the craziest and funny videos”, which are commonly called memes and viral videos. This Spanish YouTuber is extremely successful since they are third at the global level as per the SocialBlade grading. In this first example, the predominance is already evident of a highly decanted content towards humor and comedy, in its most childish aspect. Polymediation is also evident: First, in being a specific channel, it has different content windows with both real images and animation, tabs for the community, and related channels and buttons to link with other social networks, like Facebook and Twitter. These qualities were replicated in all the samples of my research. The only other Spanish YouTuber that approaches TheChacal547 in the Social Blade rank is elRubius, albeit in position #279 (Figure 4) [38].

Figure 4.

Frontpage of the YouTube channel, elRubius.

Considering the total number of world subscribers, elRubius is in 18th position, ranking 92nd in the world in video views (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Youtuber, elRubius, in 18th position in terms of subscribers and 92nd in terms of video views worldwide. 5 May 2018.

On 5 January 2019, elRubius climbed up to 13th position (32 million subscribers) and VEGGETTA777 to 27th position (25 million subscribers). There were no other Spanish YouTubers in the global top 50. Some other Spanish language channels were listed: HolaSoyGerman (35 million subscribers) and their second channel, JuegaGerman (31 million subscribers), both from Chile, Badabun (31 million subscribers, Mexico), and Fernanfloo (31 million subscribers, El Salvador).

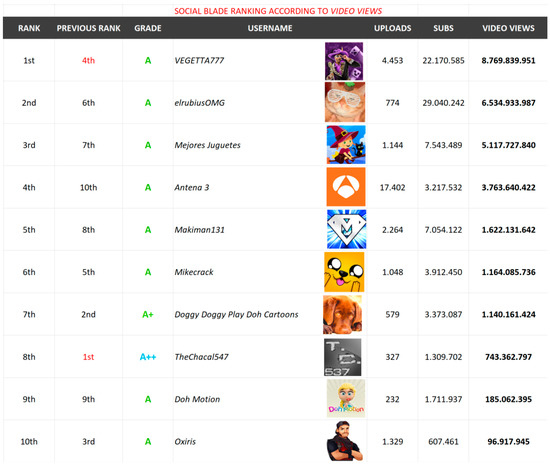

3.1. Video Views

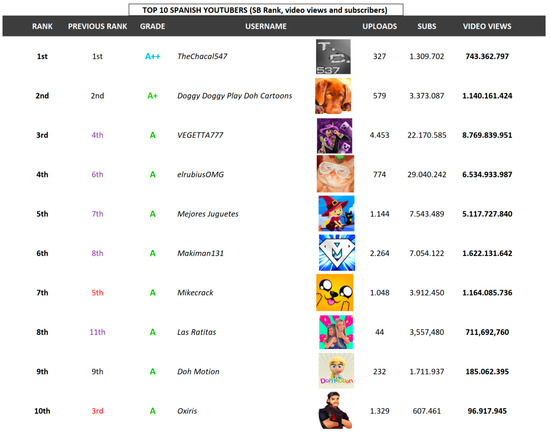

The first chart (Figure 2) with the 10 top Spanish YouTubers is sorted by the SB ranking. However, when sorted by video views (Figure 6), there are some interesting changes.

Figure 6.

Social Blade ranking according to video views.

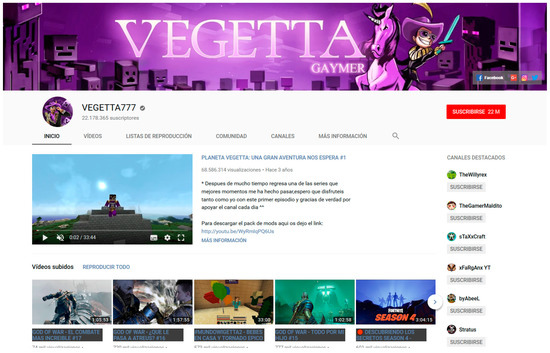

In this case, only VEGETA777, elrubiusOMG, Mejores Juguetes, and Antena 3 (TV channel) remain on the list. I discarded the latter as it adds distortion because it is a Spanish national broadcaster with a relatively professional and large team that are responsible for its content. VEGETA777 is a videogame-type channel as you can see on their website (Figure 7) [39].

Figure 7.

Front page of the YouTube channel VEGETTA777.

This is the description of this channel on their website: “♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥ PURPLE UNICORN ♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥”. The channel description provided on the website is as follows: “This is a channel dedicated to video games directed by a guy [sic] who loves unicorns and lives with a killer elf in his room, if you subscribe to it you run the risk of falling into my madness, and it’s not only me who says that, also the woman who appears at night on the roof of my room! A litle kisssss ^^”.

There is a significant narcissistic syntactic structure in which he refers to himself in the third person and, without a lack of continuity, he starts using the first person. Again, an appeal in a naïve style is used to appeal to very young users.

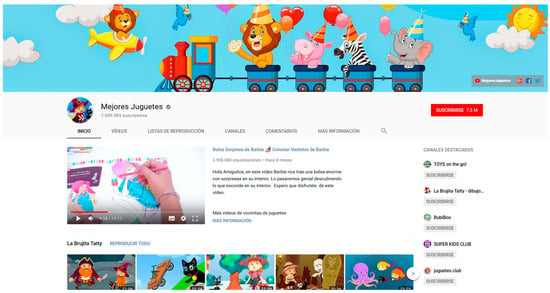

The third in the ranking with more video views is Mejores Juguetes (“Best Toys” in English) [40] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Front page of the YouTube channel, MEJORES JUGUETES.

Since this is a channel for little children where toys are unboxed, the channel is a paradoxical case of this childish style, although in the description, she says that “it is an entertainment channel for children of all ages and even for their parents” [40]. The channel also has an animation series, La brujita Tatty (“Little witch Tatty”); but the creator, a woman who lives in Barcelona, keeps her name a secret.

3.2. Subscribers

Finally, regarding the number of subscribers, the majority of YouTubers from the original SocialBlade ranking disappear: Only elRubius and VEGETTA777 remain (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Social Blade ranking according to subscribers. Source: SocialBlade.com.

The key problem with this methodology is that it introduces distortions, like the aforementioned Antena 3, and does not resolve the problem of the weighting between video views and subscribers. So, I propose to cross all three possibilities without that kind of distortion, and to give preference to the SB rank according to their highest rank: A++ and A+. From this point on, I focus on video downloads and the number of subscribers, which is probably the most easily manipulated criterion. From this mixed method, I obtained a list of the 10 most relevant youtubers in Spain (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Social Blade ranking of 10 top Spanish YouTubers in descending order: SB Rank, video views, and subscribers.

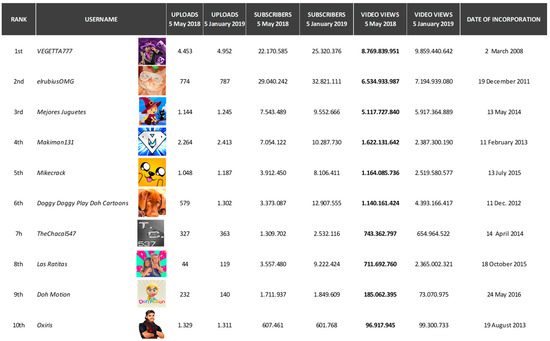

The list in Figure 10 is a much more balanced list. In purple are the YouTubers that rise with respect to the original SB chart, and in red are those that descend. To even better balance the evolution of each Youtuber in these results, it would be helpful have the total visualizations since each one of these channels was created. In this case, the data are offered directly by YouTube (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Rank per total number of video views on 5 May 2018 of 10 top Spanish YouTubers in descending order. Source: YouTube.

In this case, the top ranked channel is VEGETTA777 closely followed by elRubius. However, the latter channel was three years younger (as of 5 May 2018) and only had 775 videos against the 4453 of the first. However, elRubius has seven million more subscribers. The YouTuber that follows in the ranking, Mejores Juguetes, has only one-third of the subscribers of the first two with only 1500 million views less than elRubius and the former was created three years later than this one.

The oldest channel—the first in the ranking—was created only 10 years ago, and the average age of these successful channels is approximately 4.5 years.

As for the evolution during the nine months since making the synchronous cut until 5 January 2019, the majority of cases are consistent in the first three positions: A growth of about 1%—2% per month in both subscribers and views, which accounts for the maturity of these channels in the top of the ranking. However, from fourth place down, the variability is much greater, with Mikecrack doubling the figures, or Doggy Doggy Play Doh Cartoons and Las Ratitas tripling these.

Finally, this table provides a current map of the audiovisual genres: The top positions belong to the stable non-child video games genre (meaning that they are aimed at adults). From the third position on, considerable variability is observed, with a clear tendency toward childish genres. I then examined this more closely.

3.3. YouTubers Genres

Socialblade.com uses these eight categories or macro-genres that would cover virtually all YouTuber content: (1) Autos and vehicles, (2) comedy, (3) education, (4) entertainment, (5) film, (6) gaming, (7) science and technology, and (8) shows. From these, only entertainment appears in the 10 Top Spanish YouTubers. To be more specific, I propose the subgenres that can be deduced from this group: (1) Memes (fiction and reality), (2) children (commercial products and videogames for children, gaming), and (3) videogame (gaming not only for children). These three sub-genres could be classified into the traditional genre of comedy. For this, I propose the chart provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subgenres inside the entertainment SB genre in top 10 Spanish YouTubers (5 May 2018).

I also propose a tentative age distribution assuming that SB does not offer this service. Three large age groups were established: Young, adult, and old. I was then most interested in the thresholds, whose typology for the youth were divided into childhood (up to five years old), puberty or middle childhood (up to 12—14 years), and adolescence (until 19 or 20 years old) [41]. Therefore, given the generic content I analyzed, halfway between childhood and puberty may be a good limit, and this could specifically be eight years of age (Table 2).

Table 2.

Tentative age distribution according to the number of subscribers and video views in the top 10 Spanish YouTubers (5 May 2018).

Note that the difference among the subscribers and video views is because, in Table 2, I included some of the Youtuber channels from several subgenres, as is the case of elRubiusOMG, since this channel is mainly dedicated to the commentary of videogames and to broadcasting the experience of elRubius himself playing. However, memes also have some weight in the total content, so it was difficult to classify the channel in a single sub-genre. The total number of subscribers by genre is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Total number of subscribers per genre in the top 10 Spanish YouTubers (5 May 2018).

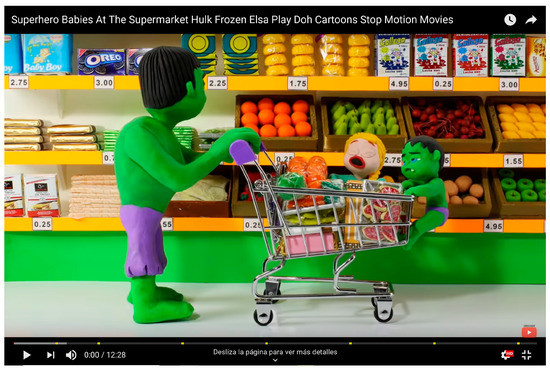

In this case, I added elRubiusOMG’s figures only to the videogame column. The most important observation here is that the youtubers related to the videogames genre have the most subscribers: Almost double those related to children’s content. The videogames genre could also be considered as being aimed at children; however, I think that the genre can be differentiated among the other main genres. An example is this photo captured from a video with 17,094,046 views [42] in the Doggy Doggy Cartoons channel (Figure 12), which shows the kind of YouTuber content that I think is exclusively aimed at children (under eight years old). The second picture was captured from a gamer video [43] published by elRubius (Figure 13), also childish, but maybe more aimed at children above the age of eight years.

Figure 12.

Superhero Babies at the Supermarket Hulk Frozen Elsa Play Doh Cartoons Stop Motion Movies. © Doggy Doggy Cartoons.

Figure 13.

La kill legendaria a Thanos/The Legendary Thanos Killing|Fornite. © elrubiusOMG.

To argue my hypothesis about the childishness of successful YouTubers’ content, the video published by Doggy Doggy Cartoons has almost four million more views than elRubius’. Perhaps a corrective factor or handicap should be considered in favor of elRubius when considering the date of publication of both videos: 21 December 2017 and 8 May 2018. As, in both cases, several months have elapsed since its release, there seems to be no balancing effect or change that elRubius would overcome the number of video views of the first.

A final combination of all the collected quantitative data is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Total number of subscribers and video views per genre in the top 10 Spanish YouTubers (5 May 2018).

This table provides revealing data. Of the approximate total number of subscribers to successful Spanish YouTubers’ channels (about 81 million) on the date of analysis, approximately 36% would be under eight years old (about 29 million) with genres focused on children’s content, and the remaining 64% would also be focused on pseudo-childish content. From these data, I concluded that the average user of this kind of channel in Spain would be less than eight years old and consumes mainly children’s content. If this relevant age category is not considered in terms of total numbers, the average Spanish subscriber would be older than eight years old and consumes content specifically related to videogames (aimed at them) and memes.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In reference to my objectives proposed in this paper, I concluded that: (1) In terms of gender or/and sex visualization, most YouTubers are male. (2) The degree of originality can be considered as very low, due to both the uniformity of the content among the different channels and to the minimal variety of the narrative strategies and staging within each particular channel, which reminds us of primitive cinema. These are videos made with professional means of production, but whose creation tends to amateurism or, at least, to a certain immediacy. (3) To answer the question as to whether YouTubers’ channels by themselves compose a totally new audio-visual genre, I think that these channels are a new audiovisual genre that, despite the minimal originality when compared with other YouTuber channels, display unique features, such as channels with polymediation, although these are not too developed.

To answer the question posed by McRobie [15], these YouTubers do not appear to have “a new radical voice”. Instead, these channels resemble the Amazon-type monetization that is typical for YouTube content. However, these channels are also related to the monetization of self-centeredness or, as Duffy defined, to the mercantilization of a certain vocation related to the pregnant world of communication. This, when mixed with the different kinds of narcissism of YouTubers and the user themselves [3,4,5,6,7], exceeds what a Marxist critical analysis of mercantilist Neoliberalism could provide.

Burgess and Green [13], Jenkins [17], Sabich and Steinberg [18], and Lange [19] pointed out how YouTube is part of a participatory or connected culture—a community that, in most cases, is quite poor considering that it is mainly based on “likes” and “dislikes”, and on a basic commentary chat structure below the video window. Polymediation would require a deepening in the philosophy of the concept, for example, with the possibility for the users to “comment” with their own produced videos, or editing the videos uploaded by each YouTuber. With even more open communication, all the possibilities of polymediation could be applied. The current structure of the Youtuber ecosystem reinforces the influence of the YouTuber and their success. However, I think that in the medium term, polymediation will be a major limitation of the creativity and evolution of this ecosystem based on the accentuated generational bias that requires a rethinking of the whole ecosystem.

My research has certain limitations, both at the quantitative and qualitative levels. Of the former, a limitation was caused by the data being gathered on a single day, though I was able to integrate a brief comparison with subsequent data nine months later (Figure 11). Even without this comparison, this quantitative level allowed me to observe a clear trend in the goal of classifying successful audiovisual genres. I provided a finding that may be significant, but needs to be tested in other research: The obvious user age bias that problematizes the future development of these YouTuber channels. Qualitative limitations are always inherent if simply compared with the quantitative methods, but the qualitative methods here were especially necessary given the youth of this phenomenon in which the data’s historical series are limited. As such, qualitative data can contribute significantly to this field. Polymediation is speculative, but I think it can contribute to the understanding and future development of the YouTube phenomenon.

In summary, my analysis could have been more comprehensive if it had included a lengthened body of research, both temporarily extending the time slot as well as more nationalities. However, my goal was also to propose a method that could be applied by other researchers. I have proposed a straightforward method so the results can be replicated in other cultures.

To finish, the concept of polymediation can be related to the successful audiovisual subgenres in Spain that I deduced. These are based on content aimed at specific audiences and with an emphatic type of communication that is related to polymediation, as this is a type of communication with which it is possible to connect, to invent qualitative new content, or reinvent the type of contact between the YouTuber and the user on a daily basis. Polymediation is reinforced by the feeling of community and the verification of identities that these audiovisual genres imply, especially in children, but also in teenagers if video-games are considered.

The definition of polymediation also provides some interesting research questions, especially in relation to the new possibilities for both narrative and business. I am not referring only to something so direct as direct monetization—so common in economics studies on YouTubers—and their professional projects. Polymediation provides research avenues in many aspects, including even sociological research, considering Baumann’s liquid modernity, such as when Calka sustains that polymediation shows how “the complex relationship between media, identity, and performance is necessarily in flux” [28] (pp. 27, 28). This flux that YouTubers are unconsciously building must be considered, although, given the style and content of the dominant genres in their channels, it is still an immature flow, but one that marks a clear path. If one agrees with Calka that our identities change with the changes in the technological landscape of the media (ibid.)—the continuous flow related to Baumann thought—one must consider the bias that mediates a large part of the adults in our society by specific YouTubers genres that indirectly and proportionally offer content that do not respond proportionally to the cultural richness of a culture that has been able to offer the most sophisticated communication network in history.

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study in which polymediation was related to YouTube success. My results indicate that polymediation has not been fully developed in YouTube channels, a kind of audiovisual entertainment. I envision a difficulty and two possibilities. Firstly, according to the data I presented, this is a fairly mature market in which approximately the five top YouTubers have sufficient subscribers and views to live off the income and are able to set trends, so specificity is a difficulty for newcomers. As for the possibilities, both the YouTube platform and the analyzed channels are recent, and both have provided examples of creativity and flexibility since its creation, which are characteristics of polymediation. Seeking survival may produce radical changes in the medium term. Secondly, YouTube is the paradigm—although in its most basic expression—of polymediation. However, traditional on-line content platforms (OTT), such as Netflix or Amazon, are degrading the ecosystem of immediate consumption and in no entertainment area is YouTube the king. This can be expected to spur YouTube—and YouTubers themselves—to implement new polymediation features that would provide YouTube channels an advantage over OTTs. This advantage is yet to be seen, but the situation suggests that it will be along the lines of polymediation. When I was finishing this article, on 28 December 2018 Netflix had just released Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, the first interactive chapter of the series, in which the viewer makes decisions for the main character, being asked at various points to make a choice which affects the storyline [44]. I think that change will accelerate as the generational bias disappears, which is when the users of these channels aged. Considerably more work is needed to determine its further development.

More information on polymediation would help with the establishment of a greater degree of accuracy on this matter. My future lines of research will be developed along these lines, in trying to analyze how the possibilities offered by polymediation can be integrated into successful YouTube channels. I will analyze similar YouTubers’ examples as proposed here, but from different cultures, such as the North American, Russian, or Chinese cultures. Later, I will compare the results to look for similarities and differences to verify to what extent the integration of polymediation can be generalized at the global level. My intent will be to propose a guide both methodological—for the analysis of the YouTuber phenomenon—and professional to provide a minimum guideline of success for future YouTubers, as well as a sufficient ethical guideline that is globally valid.

The aim of the present research was to examine the predominant audiovisual genres of the successful YouTube channels in Spain and their relationship with polymediation. This led me to a discussion the creation of the identity of their users. This was not the focus of this paper, but from a sociological point of view, for example, from Bauman [45], identity is created from the various alternative offers that are present in our reality (p. 16). It is nowadays accepted that texts, those that surround us and compose our daily life, build our consciousness, and the quality of these texts qualitatively influence our identities. “The media supply ‘virtual [...] substitute’ and ‘imagined extra territoriality’ to the multitude of people who are denied access to real life” (p. 97). Therefore, my analysis expands the field of study mapped here from the data collected, as hypothesized. I attempted to think about polymediation in YouTuber channels beyond the technical possibility, for example, analysing how it can influence the creation of mature identities that can face the challenges of our liquid society.

From a more philosophical viewpoint, Byung-Chul Han [46] examined this possibility when claiming that the Internet does not really assist human intercommunication, but enables contact with peers and distances strangers and those who are different. Pariser thinks that all this would narrow our horizon as "we are entangled in an endless loop of the self and, ultimately, lead us to a ‘self-propaganda that indoctrinates us with our own notions’” [47]. A further comprehension of what polymediation could add might help to overcome this level of childish self-centeredness.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad [Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness], Ref. CSO2016-74977-R. “Análisis del fenómeno Youtubers en España: Una exploración para identificar los vectores de cambio del mercado audiovisual” [“Analysis of the YouTubers Phenomenon in Spain: An Exploration to Identify the Vectors of Change in the Audio-visual Market”], 2016/00171/010, Proyecto I+d Plan Nacional. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Roberts, C.; Muscarella, V. OTT Overview; Digital EMA (Entertainment Merchants Association): North Hollywood, CA, USA, 2015; p. 1. Available online: http://www.entmerch.org/digitalema/white-papers/defining-digital-distributi.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2019).

- Torres, L. Aproximación a un modelo de representación virtual lúdico (MRVL). Virtual Self, narcisismo y ausencia de sentido. Cuad. 56. Cuad.Cent. Estud. Dis. Com. 2016, [Approach to a Playful Virtual Representation Model (MRVL). Virtual Self, Narcissism and Lack of Meaning]. 56, 227–250. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/11522141/Aproximación_a_un_modelo_de_representación_virtual_lúdico_MRVL_._Virtual_Self_narcisismo_y_ausencia_de_sentido (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Ksinan, A.J.; Vazsonyi, A.T. Narcissism, Internet, and Social Relations: A Study of Two Tales. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 94, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In Levy, F. Becoming a Star in the Youtube Revolution; Alpha. A member of Penguin Group: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cocker, H.L.; Cronin, J. Charismatic authority and the YouTuber: Unpacking the new cults of personality. Market. Theory 2017, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashman, R.; Patterson, A.; Brown, S. ‘Don’t Forget to Like, Share and Subscribe’: Digital Autopreneurs in a Neoliberal World. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, P.G. Videos of Affinity on YouTube. In The YouTube Reader; Snickars, P., Vonderau, P., Eds.; National Library of Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009; pp. 70–88. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Cervantes. El español: Una lengua viva. Informe 2017. Available online: https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/espanol_lengua_viva/pdf/espanol_lengua_viva_2017.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2018).

- Lindley, C. Narrative, Game Play, and Alternative Time Structures for Virtual Environments. In Technologies for Interactive Digital Storytelling and Entertainment: Proceedings of TIDSE 2004; Göbel, S., Ed.; Springer: Darmstadt, Germany, 2004; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Berlant, L. Cruel Optimism; Duke University Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, A. Resistance Up in Smoke: Analyzing the Limitations of Deliberation on YouTube. Crit. Stud. Med. Commun. 2009, 26, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.J.; Owen, T.; Brown, P.D.; Hauka, C.; Rashidian, N. The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley Reengineered Journalism; Columbia Journalism School, Tow Center for Digital Journalism: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burguess, J.; Green, J. The Entrepreneurial Vlogger: Participatory Culture: Beyond the Professional-Amateur Divide. In The YouTube Reader; Snickars, P., Vonderau, P., Eds.; National Library of Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009; pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, B.E. (Not) Getting Paid to Do What You Love. Gender, Social Media, and Aspirational Work; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2017; p. XII, (Preface). [Google Scholar]

- McRobie, A. Be Creative: Making a Living in the New Culture Industries; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Burguess, J.; Green, J. Youtube. Online Video and Participatory Culture; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. vii, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture. Where Old and New Media Collide; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2006; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sabich, M.A.; Steinberg, L. Discursividad youtuber: Afecto, narrativas y estrategias de socialización en comunidades de Internet. Mediterr. J. Commun. 2017, 8, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, P. Publicly Private and Privately Public: Social Networking on YouTube. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorriaga, A.; Monge, S. The Professionalization of YouTubers: The Case of Verdeliss and the Brands. Rev. Latina Comun. Soc. 2018, 73, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, V.; Pastor-Ruiz, Y.; Abarrou-Ben-Boubaker, S. YouTubers Videos and the Construction of Adolescent Identity. Comunicar 2018, 55, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Serrano, M.; Herrero-Diz, P. Unboxing and Brands: Youtubers Phenomenon through the Case Study of EvanTubeHD. Prisma Soc. 2016, 1, 90–130. [Google Scholar]

- Scolari, C.A.; Fraticelli, D. The case of the top Spanish YouTubers Emerging Media Subjects and Discourse Practices in the New Media Ecology. Convergence Int. J. Res. New Media Technol. 2017, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolari, C.A. The Grammar of Hypertelevision. An Identikit of the Convergence Age Television (Or How Television is Simulating New Interactive Media). J. Vis. Lit. 2009, 28, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzosa, M.I. Youtubers y otras especies. El fenómeno que ha cambiado la manera de entender los contenidos audiovisuales; Ariel, Fundación Telefónica: Madrid, Spain, 2017; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://socialblade.com/youtube/help/what-is-sbrank-all-about (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Madianou, M.; Miller, D. Polymedia: Towards a New Theory of Digital Media in Interpersonal Communication. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2012, 16, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calka, M. Polymediation. The Relationship between Self and Media. In Beyond New Media: Discourse and Critique in a Polymediated Age; Herbig, A., Herrmann, A.F., Tyma, A.W., Calka, M., Denker, K.J., Dunn, R.A., Henderson, C., Manning, J., Stern, D.M., Willits, M.D.D., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, D. Identity Related Crime in the UK. London: Government Office for Science. In Foresight Future Identities. Final Project Report; The Government Office for Science: London, UK, 2013; p. 25. Available online: http://tedcantle.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/074-Foresight-Future-Identities-2013-Report-by-the-Government-Office-for-Science1.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- Baym, K. Personal Connections un the Digital Age, 2nd ed.; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Couldry, N. Digital Storytelling, Media Research and Democracy: Conceptual Choices and Alternative Futures. In Digital Storytelling, Mediatized Stories: Self-Representations in New Media. Digital Formations (52); Lundby, K., Ed.; Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, S. On the mediation of everything: ICA presidential address 2008. J. Commun. 2008, 59, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N. Media, Society, World: Social Theory and Digital Media Practice; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hepp, A. Transculturality as a Perspective: Researching Media Cultures Comparatively. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung 2009, 10, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, S. Changing Media, Changing Language: The Mediatization of Society and the Spread of English and Medialects’. In Proceedings of the 57th ICA Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 23–28 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, T.L. The World is Flat. A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century; Picador: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- TheChacal547. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/user/thechacal547 (accessed on 17 December 2018).

- elRubius. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCXazgXDIYyWH-yXLAkcrFxw (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- VEGETTA777. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/user/vegetta777 (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Mejores Juguetes. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/user/MejoresJuguetes (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Martín Ruiz, J.M. Los factores definitorios de los grandes grupos de edad de la población: Tipos, subgrupos y umbrales. Scripta Nova 2005, IX, 190. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-190.htm (accessed on 28 December 2018).

- As of December 28, 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-AW1WpH8VPQ (accessed on 28 December 2018).

- 13,093,648 views on December 29, 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fTc8bwoSv4M&t=2s (accessed on 29 December 2018).

- Available online: https://www.netflix.com (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Bauman, Z. Identity. Conversations with Benedetti Vecchi; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B. La expulsión de lo distinto [Die Austreibung des Anderen, 2016]; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; Volumen 5.11; Available online: http://www.emanantial.com.ar/archivos/fragmentos/HanLEDFragmentopdf (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Pariser, E. Filter Bubble. Wie wir im Internet Entmündigt Werden; Carl Hanser: Munich, Germany, 2012; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).