The Conventional and Alternative Therapeutic Approaches in Arterial Stiffness Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

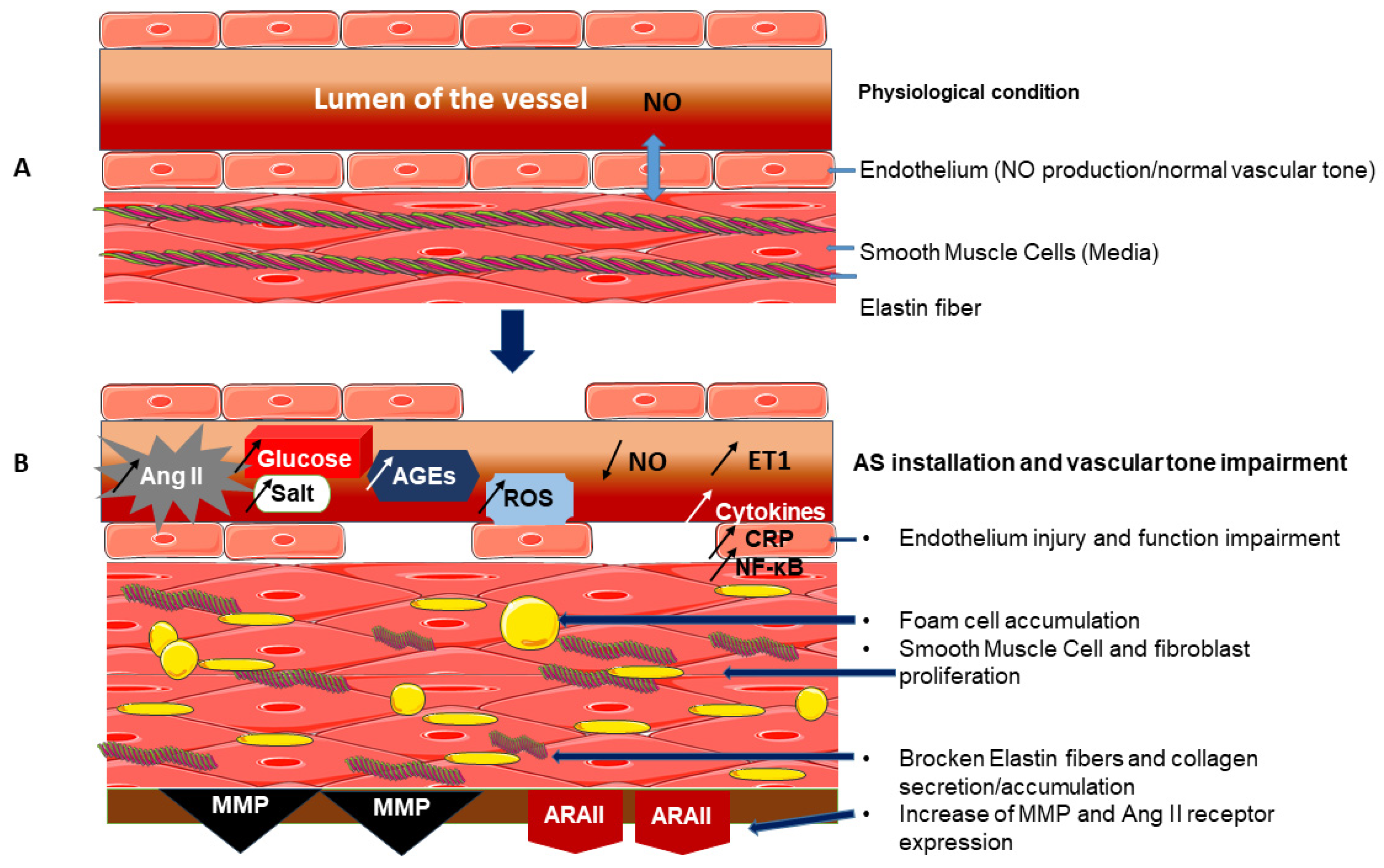

2. Care Approaches and Tools to Modulate the Mechanisms of AS Development

2.1. Parameters Confirming AS

2.2. Existing Approaches Used in AS Prevention and Treatment

2.2.1. Physical Exercise and Other Healthy Approaches Involved in AS Prevention

- The clinical trial PULSE (Blood Pressure Utilizing Self-monitoring after Exercise) by Kiernan et al. [41], assessing post-exercise cardiovascular benefit, concluded that both hypotension and vasodilation were observed as one of post-exercise phenomenons due to hemodynamic adjustments occurring from aerobic or exercise recovery, which should be controlled to avoid post-exercise cardiovascular instability. Indeed, a clinical study by Liu et al. [42], conducted on 70 prehypertensive patients, demonstrated the crucial role played by the central baroreflex pathway in decreasing BP, inducing the phenomenon called post-exercise hypotension. Brandão Rondon et al. [43] enrolled 24 elderly hypertensive patients and confirmed this observation, suggesting that post-exercise hypotension is due to peripheral vascular resistance reduction. According to Santos et al. [44], a crossover trial conducted on 20 patients with resistant hypertension supported these findings.

- According to a randomised clinical trial conducted in 16 type 2 diabetic patients, Myette-Côté et al. [45] demonstrated that a low-carbohydrate diet induced a reduction in blood glucose levels and mobilised peripheral blood monocytes. This glucose-lowering effect was more beneficial when combined with post-meal walking. In agreement, Chiang et al. [46] studied the effects of moderate-intensity exercise on blood glucose response in 66 type 2 diabetes patients through a prospective longitudinal evaluation. In this clinical trial, blood glucose progressively declined and stabilised over twelve weeks of training. Moreover, exercise in the afternoon or evening had increased ability to induce lower glucose levels compared to those found after morning exercise. Both prospective observational studies, conducted on 197 and on 100 pregnant women, respectively, showed that even maintaining moderate and regular physical activity, as well as applying long-term resistance exercise, would be recommended for pregnant women displaying gestational diabetes [47,48]. Motahari-Tabari et al. [49] conducted a randomised clinical study in 55 type 2 diabetic women, which promoted low plasma glucose due to medical treatment combined with aerobic exercise to target insulin resistance.

- Fernberg et al. [50] assessed the relationship between sedentary behaviour and cardiovascular disease in 658 young healthy and non-smoking adults, participating in the LBA (cross-sectional Lifestyle, Biomarkers and Atherosclerosis) trial. A progressive decrease in AS was observed among people practising a moderate or vigorous physical activity. Park et al. [51], in a randomised clinical trial involving 72 patients with peripheral artery disease, suggested that an aquatic walk exercise could be an effective therapy to reduce AS, improving heart rate, cardiorespiratory capacity, and strengthening muscles and physical function. According to Park et al. [52], in a clinical pilot study involving 20 patients, a combination of aerobic and resistance exercise effectively enhanced the quality of life in obese older adults with concomitant AS reduction. This observation was confirmed by Endes et al. [53] following the SAPALDIA 3 Cohort study in 1908 elderly people, which showed low AS after vigorous physical activities. Interestingly, a Maastricht Study by Vandercappellen et al. [54], conducted in 1699 patients, proposed that higher-intensity physical activity might be a main strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease risk, such as AS, particularly in type 2 diabetes subjects. The Stamatelopoulos et al. [55] cross-sectional study, involving 625 healthy subjects, concluded that PWV reduction occurred in normal-weight postmenopausal women after physical activity.

- Physical exercise restores cardiovascular function. Benefits include parasympathetic nervous system stimulation and the proper use of glucose, which might prevent AS development associated to diabetes and hypertension.

- Other lifestyle changes, as well as physical activity, could have beneficial effects. For instance, Takami and Saito’s [56] observational study, conducted in 70 subjects who stopped smoking, suggested an essential age-related reduction in vascular stiffness. Moreover, a diet therapy containing omega-3 (ω-3) supplementation reduced PWV and CAVI in metabolic syndrome and hypertensive patients, enhancing arterial distensibility. As reported by Sacks et al. [57] in DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), a randomised trial conducted in 412 participants, the diet was effective in reducing AS. This non-pharmacological approach was mainly able to decrease oxidative stress, preventing vascular free radical deleterious effects. This finding was confirmed by Imamura et al. [58] in a randomised controlled study involving 50 type 2 diabetic patients, demonstrating that resveratrol treatment decreased CAVI and SBP without significant changes in metabolic parameters.

2.2.2. Antihypertensive Drugs in AS Treatment

- Vascular muscle modulation was evidenced in 25 healthy subjects and 25 arteriosclerotic patients [59]. Vascular relaxation by nitroglycerin reduced CAVI and repaired AS injuries in muscular arteries.

- System or receptor blocking/inhibiting: RAAS inhibitors were the most effective in AS treatment, probably by regulating vascular wall fibrosis formation. Targeting arterial structure is the most successful AS therapy. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs) reduced AS in patients with resistant hypertension without improving arterial compliance. Furthermore, a prospective clinical study, conducted by Palić et al. [60] on 31 hypertensive patients, proved AS reduction after zofenopril treatment. As demonstrated by Jung et al. [61], in a study where telmisartan was administered to 39 patients with essential hypertension, the treatment decreased Brachial–Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity (ba-PWV) and increased Flow-Mediated Dilation (FMD). Mahmud and Feely [62] described the effects of β-adrenergic antagonists, or Beta-Blockers (BBs), in 40 hypertensive patients, demonstrating that atenolol and nebivolol diminished BP and PWV associated with NO production and vasodilation. According to a trial by Sasaki et al. [63], involving 40 type 2 diabetic patients affected by hypertension and nephropathy, Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs), such as efonidipine, decreased CAVI with a reduction in circulating aldosterone and the oxidative stress marker 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine. As shown by Wang et al. [64], in a randomised double-blind clinical trial conducted in 269 hypertensive patients, a twenty-week treatment with amlodipine and lacidipine decreased ba-PWV and reduced AS. These classes of drugs are used especially for vascular contraction inhibition and must be combined with other antihypertensive compounds to overcome AS.

- Direct Renin Inhibitors (DRI): Virdis et al. [65], in a three-month study involving 50 patients with essential hypertension, showed that aliskiren decreased BP, central Pulse Pressure (PP), Augmentation Index (AIx), and aortic PWV. In addition, in 24 type 1 diabetic patients, Cherney et al. [66] reported that aliskiren enhanced endothelial function by increasing the FMD. These effects reduce AS in both diabetic and hypertensive patients.

2.2.3. Antidiabetic Drugs Reducing AS

- Regarding sulfonylureas: a randomised clinical study by Nagayama et al. [68], using glimepiride administered to 40 type 2 diabetic patients, demonstrated that a six-month treatment reduced CAVI and lipoprotein lipase (an insulin resistance indicator), as well as the oxidative stress marker, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine.

- Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, called gliflozins, were known to improve FMD, while Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors decreased PWV. Two clinical studies, involving 60 and 40 type 2 diabetic patients, respectively, demonstrated AS reduction in both groups [71,72]. As shown in clinical trials by Bosch et al. [73] in 58 type 2 diabetic patients and by Cherney et al. [74] in 42 type 1 diabetic patients, empagliflozin reduced SBP and pulse pressure-associated AS related to high-sensitive inflammatory marker C-reactive protein (hsCRP) reduction. The susceptible mechanisms of these beneficial effects were proposed by Neutel et al. [75] and Soares et al. [76] in aged mice models, showing the reduction of collagen type I and TGF-β protein expression in the media of the infrarenal aorta of aged mice. At the mesenteric artery level, the treatment enhanced endothelial function, characterised by the phospho-eNOS/eNOS ratio increase and by the reduction of the oxidative stress marker, Malondialdehyde (MDA).

- In a similar way, a GPL-1 RA, liraglutide, used by Lambadiari et al. [71] in a clinical trial, reduced cf-PWV and increased FMD, indicating AS inhibition. These effects were associated with MDA reduction, suggesting an antioxidative property of this drug in humans. Experimental studies, using diabetes induced by streptozotocin (STZ) in rats and in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), demonstrated that liraglutide inhibited Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, or NOX, via Protein Kinase A (PKA) activation. This finding was confirmed by the inhibition of both gp91phox and p22phox in endothelial cells. Liraglutide also showed an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing Nuclear Factor Kappa-B (NF-κB) protein expression/activation in the presence of Tumour Necrosis Factor-Alpha (TNF-α) [77,78].

- DPP4 inhibitors (DPP4-i), also called gliptins, have effects on endothelial cell homeostasis and proliferation. As reported by Stampouloglou et al. [79], in a clinical trial conducted in 118 diabetic patients, DPP4-i decreased PWV in addition to weight loss. In HUVECs exposed to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and high glucose, anagliptin increased cell viability and inhibited cell senescence by reducing the release of interleukins and pro-oxidant molecules, such as interleukin 1-β (IL-1β) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [80]. In an in vivo study using the Aortic-Banded Mini Swine model, saxagliptin-dependent vascular stiffness reduction was due to the decline of NF-κB-induced inflammation, AGEs, and nitrotyrosine in coronary arteries [81].

2.2.4. Cholesterol-Lowering Drugs and AS

2.2.5. Probable Drug Combinations Used to Treat AS

2.3. Drug Molecular Structure-Activity Relationship

2.4. Plants Used in Vascular Stiffness Alleviation

2.4.1. Methodology

2.4.2. The Plants of the Araliaceae Family

2.4.3. The Plants of the Apiaceae Family

2.4.4. The Plants of the Lamiaceae Family

2.4.5. The Plant of the Amaryllidaceae Family

2.4.6. The Plant of the Theaceae Family

2.4.7. The Plant of the Caricaceae Family

2.4.8. The Plant of the Cucurbutaceae Family

2.4.9. The Plant of the Zingiberaceae Family

2.4.10. The Plant of the Clusiaceae Family

2.4.11. The Plant of the Cactaceae Family

2.4.12. The Plant of the Myrsinaceae Family

2.4.13. The Plant of the Thymelaeaceae Family

2.4.14. The Plant of the Phyllanthaceae Family

2.4.15. The Plant of the Moringaceae Family

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme |

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| AGEs | Advanced Glycation End-products |

| AIx | Augmentation Index |

| AMPK | Adenosine Monophosphate–Activated Protein Kinase |

| Ang II | Angiotensin II |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein 1 |

| API | Arterial Pressure Index |

| ARA II | Angiotensin II Receptors |

| ARBs | Angiotensin Receptor Blockers |

| AS | Arterial Stiffness |

| AT1 | Angiotensin II Receptor Type 1 |

| AVI | Arterial Velocity Pulse Index |

| ba-PWV | Brachial–Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity |

| BBs | Beta-Blockers |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CAVI | Cardio–Ankle Vascular Index |

| CCBs | Calcium Channel Blockers |

| cf-PWV | Carotid–Femoral Pulse Wave Velocity |

| cGMP | Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| Cu/Zn-SOD | Copper/zinc-containing Superoxide Dismutase |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| DPP4i | Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitors |

| DRI | Direct Renin Inhibitors |

| EDHFs | Endothelium-Derived Hyperpolarising Factors |

| Einc | Incremental Elastic Modulus |

| Ep | Elastic modulus |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases |

| ET-1 | Endothelin 1 |

| EVR | Elastic Vascular Resistance |

| FMD | Flow-Mediated Dilation |

| GLP-1 RA | Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist |

| GLUT | Glucose Transporter |

| GSH | Glutathione (reduced) |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| HFFD | High-Fat-high-Fructose Diet |

| HMG-CoA | 3-Hydroxy-3-Methyl-Glutaryl-Coenzyme A |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| hsCRP | High-sensitive inflammatory marker C-Reactive Protein |

| HSD | High-salt diet |

| HUVECs | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| IFNγ | Interferon Gamma |

| IL-1ß | Interleukin 1 Beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| IRS-1 | Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 |

| KRG | Korean Red Ginseng |

| LB | Lemon Balm |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| L-NAME | N-Nitro-L-Arginine Methyl Ester hydrochloride |

| LOXL-1 | Lysyl-Oxidase-Like 1 |

| MAP | Mean Arterial Pressure |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemotactic Protein 1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MF | Metformin |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinase |

| Mn-SOD | Manganese Superoxide Dismutase |

| NaCl | Sodium Chloride |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-B |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| eNOS | endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| NOX1 | NADPH oxidase 1 |

| NOX2 | NADPH oxidase 2 |

| NOX4 | NADPH oxidase 4 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear Factor E2-related Factor 2 |

| OPG | OsteoProteGerin |

| OVX | Ovariectomized |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| PKA | Protein Kinase A |

| PKB | Protein Kinase B |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor |

| PP | Central Pulse Pressure |

| PWT | Pulse Wave Transmission |

| RA | Rosmarinic Acid |

| Rac1 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxine Substrate 1 |

| RAGE | AGEs receptors |

| RAAS | Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System |

| RhoA | Ras Homolog family member A |

| RI | Reflexion Index |

| ROCK | Rho-associated Kinases |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| SD | Sprague–Dawley |

| SGLT-2 | Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 |

| SHR | Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| Smad | Suppressor Mothers Against Decapentaplegic |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| STZ | Streptozotocin |

| TAG | Triacylglycerol |

| TBARs | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive substance |

| TC | Total Cholesterol |

| TE | Tropoelastin |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TGF-ß1 | Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 |

| THC | Tetrahydrocurcumin |

| TNF-α | Tumour Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| VMSC | Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell |

| WC | Waist circumference |

| WKY | Wistar Kyoto |

| ω-3 | Omega-3 |

References

- Avolio, A. Arterial Stiffness. Pulse 2013, 1, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvim, R.D.O.; Santos, P.C.J.L.; Bortolotto, L.A.; Mill, J.G.; Pereira, A.D.C. Arterial Stiffness: Pathophysiological and Genetic Aspects. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Sci. 2017, 30, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacolley, P.; Regnault, V.; Laurent, S. Mechanisms of Arterial Stiffening: From Mechanotransduction to Epigenetics. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, J.R.; Guzik, T.J.; Touyz, R.M. Diabetes, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Disease: Clinical Insights and Vascular Mechanisms. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018, 34, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, D.R.; Monnier, V.M. Molecular Basis of Arterial Stiffening: Role of Glycation—A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2012, 58, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Aroor, A.R.; DeMarco, V.G.; Martinez-Lemus, L.A.; Meininger, G.A.; Sowers, J.R. Vascular Stiffness in Insulin Resistance and Obesity. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroor, A.R.; DeMarco, V.G.; Jia, G.; Sun, Z.; Nistala, R.; Meininger, G.A.; Sowers, J.R. The Role of Tissue Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in the Development of Endothelial Dysfunction and Arterial Stiffness. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.E.; Casabianca, A.B.; Khouri, S.J.; Kalinoski, A.L.N. In Vivo Assessment of Arterial Stiffness in the Isoflurane Anesthetized Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2014, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindesay, G.; Ragonnet, C.; Chimenti, S.; Villeneuve, N.; Vayssettes-Courchay, C. Age and Hypertension Strongly Induce Aortic Stiffening in Rats at Basal and Matched Blood Pressure Levels. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e12805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.; Montezano, A.C.; Lopes, R.A.; Rios, F.; Touyz, R.M. Vascular Fibrosis in Aging and Hypertension: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safar, M.E.; Asmar, R.; Benetos, A.; Blacher, J.; Boutouyrie, P.; Lacolley, P.; Laurent, S.; London, G.; Pannier, B.; Protogerou, A.; et al. Interaction Between Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness. Hypertension 2018, 72, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, A.; Salvi, L.; Coruzzi, P.; Salvi, P.; Parati, G. Sodium Intake and Hypertension. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, N.H.; Shaw, J.E.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; Da Rocha Fernandes, J.D.; Ohlrogge, A.W.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global Estimates of Diabetes Prevalence for 2017 and Projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 138, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patoulias, D.; Papadopoulos, C.; Stavropoulos, K.; Zografou, I.; Doumas, M.; Karagiannis, A. Prognostic Value of Arterial Stiffness Measurements in Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes, and Its Complications: The Potential Role of Sodium-glucose Co-transporter-2 Inhibitors. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2020, 22, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Uricoechea, H.; Cáceres-Acosta, M.F. Blood Pressure Control and Impact on Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Critical Analysis of the Literature. Clin. Investig. Arterioscler. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 31, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabler, M.; Geier, S.; Mayerhoff, L.; Rathmann, W. Cardiovascular Disease Prevalence in Type 2 Diabetes–An Analysis of a Large German Statutory Health Insurance Database. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, E.; Delgado, E.; Fernández-Vega, F.; Prieto, M.A.; Bordiú, E.; Calle, A.; Carmena, R.; Castaño, L.; Catalá, M.; Franch, J.; et al. Prevalence, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension in Spain. Results of the Diabetes Study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2016, 69, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federfarma, T.I.S.O.H.A.; De Feo, M.; Del Pinto, R.; Pagliacci, S.; Grassi, D.; Ferri, C.; Italian Society of Hypertension and Federfarma. Real-World Hypertension Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control in Adult Diabetic Individuals: An Italian Nationwide Epidemiological Survey. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2021, 28, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raharinavalona, S.A.; Razanamparany, T.; Raherison, R.E.; Rakotomalala, A.D.P. Prévalence du syndrome métabolique et des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire chez les diabétiques de type 2 vu au service d’endocrinologie, Antananarivo. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 36, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zuo, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, A. Hypertension, Arterial Stiffness, and Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study. Hypertension 2022, 79, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, R.; Vieira, M.J.; Gonçalves, A.; Cardim, N.; Gonçalves, L. Ultrasonographic Vascular Mechanics to Assess Arterial Stiffness: A Review. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 17, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathapati, R.M. An Open Label Parallel Group Study to Assess the Effects of Amlodipine and Cilnidipine on Pulse Wave Velocity and Augmentation Pressures in Mild to Moderate Essential Hypertensive Patients. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, FC13–FC16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakura, T.; Morioka, T.; Shioi, A.; Kakutani, Y.; Miki, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Motoyama, K.; Mori, K.; Fukumoto, S.; Shoji, T.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Protein Is Associated with Arterial Stiffness in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammar, W.; Taha, M.; Baligh, E.; Osama, D. Assessment of Vascular Stiffness Using Different Modalities in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Control Study. Egypt. Heart J. 2020, 72, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T.; Ito, H. Assessment of Arterial Stiffness Using the Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index. Pulse 2016, 4, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, K.; Utino, J.; Otsuka, K.; Takata, M. A Novel Blood Pressure-Independent Arterial Wall Stiffness Parameter; Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index (CAVI). J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2006, 13, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPont, J.J.; Kenney, R.M.; Patel, A.R.; Jaffe, I.Z. Sex Differences in Mechanisms of Arterial Stiffness. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 4208–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashor, A.W.; Lara, J.; Siervo, M.; Celis-Morales, C.; Mathers, J.C. Effects of Exercise Modalities on Arterial Stiffness and Wave Reflection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Cicero, L.; Lentini, P.; Sessa, C.; Castellino, N.; D’Anca, A.; Torrisi, I.; Marcantoni, C.; Castellino, P.; Santoro, D.; Zanoli, L. Inflammation and Arterial Stiffness as Drivers of Cardiovascular Risk in Kidney Disease. Cardiorenal Med. 2025, 15, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inserra, F.; Forcada, P.; Castellaro, A.; Castellaro, C. Chronic Kidney Disease and Arterial Stiffness: A Two-Way Path. Front. Med. 2021, 23, 765924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P.; True, H.D.; Patel, J. Leukocyte trafficking in cardiovascular disease: Insights from experimental models. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 9746169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, M.; Megens, R.T.; Van Zandvoort, M.; Weber, C.; Soehnlein, O. Hyperlipidemia-triggered neutrophylia promotes early atherosclerosis. Circulation 2010, 122, 1837–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirwany, N.A.; Zou, M.H. Arterial stiffness: A brief review. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2010, 31, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, J.A.; Keaney, J.F.; Larson, M.G., Jr.; Keyes, M.J.; Massaro, J.M.; Lipinska, I.; Lehman, B.T.; Fan, S.; Osypiuk, E.; Wilson, P.W.; et al. Brachial artery vasodilator function and systemic inflammation in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation 2004, 110, 3604–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacolley, P.; Challande, P.; Regnault, V.; Lakatta, E.G.; Wang, M. Cellular and molecular determinants of arterial aging. In Early Vascular Aging; Nilsson, P., Olsen, M., Laurent, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulyan, H.; Mookherje, S.; Safar, M.E. Two faces of hypertension: Role of aortic stiffness. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2016, 10, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, G.K.; Hermansson, A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Aiello, A.; Filomia, S.; Brecciaroli, M.; Sanna, T.; Pedicino, D.; Liuzzo, G. Targeting inflammatory pathways in atherosclerosis: Exploring new opportunities for treatment. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2024, 26, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, S.E.; Robinson, A.J.B.; Zurke, Y.X.; Monaco, C. Therapeutic strategies targeting inflammation and immunity in atherosclerosis: How to proceed? Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akivis, Y.; Alkaissi, H.; McFarlane, S.I.; Bukharovich, I. The role of triglycerides in atherosclerosis: Recent pathophysiologic insights and therapeutic implications. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2024, 20, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, S.A.; Minson, C.T.; Halliwill, J.R. The Cardiovascular System after Exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Bonham, A.C. Postexercise Hypotension: Central Mechanisms. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2010, 38, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier-Melo, R.J.; Germano-Soares, A.H.; Freitas Brito, A.; Vilela Dantas, I.; Da Cunha Costa, M. Post-Exercise Hypotension in Response to High-Intensity Interval Exercise: Potential Mechanisms. Rev. Port. De Cardiol. 2021, 40, 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.; Santos, A.; Lucena, J.; Silva, L.; Almeida, A.; Brasileiro-Santos, M. Acute and Chronic Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Blood Pressure in Resistant Hypertension: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2017, 18, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myette-Côté, É.; Durrer, C.; Neudorf, H.; Bammert, T.D.; Botezelli, J.D.; Johnson, J.D.; DeSouza, C.A.; Little, J.P. The Effect of a Short-Term Low-Carbohydrate, High-Fat Diet with or without Postmeal Walks on Glycemic Control and Inflammation in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Trial. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol. 2018, 315, R1210–R1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.-L.; Heitkemper, M.M.; Hung, Y.-J.; Tzeng, W.-C.; Lee, M.-S.; Lin, C.-H. Effects of a 12-Week Moderate-Intensity Exercise Training on Blood Glucose Response in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Medicine 2019, 98, e16860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Fang, X.; Wong, T.-H.; Chan, S.N.; Akinwunmi, B.; Ming, W.-K.; Zhang, C.J.P.; Wang, Z. Physical Activity during Pregnancy: Comparisons between Objective Measures and Self-Reports in Relation to Blood Glucose Levels. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, M.; Huang, H.; Liu, C.; Huang, F.; Wu, J. Effects of Resistance Exercise on Blood Glucose Level and Pregnancy Outcome in Patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2022, 10, e002622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motahari-Tabari, N.; Ahmad Shirvani, M.; Shirzad-e-Ahoodashty, M.; Yousefi-Abdolmaleki, E.; Teimourzadeh, M. The Effect of 8 Weeks Aerobic Exercise on Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernberg, U.; Fernström, M.; Hurtig-Wennlöf, A. Higher Total Physical Activity Is Associated with Lower Arterial Stiffness in Swedish, Young Adults: The Cross-Sectional Lifestyle, Biomarkers, and Atherosclerosis Study. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Kwak, Y.-S.; Pekas, E.J. Impacts of Aquatic Walking on Arterial Stiffness, Exercise Tolerance, and Physical Function in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 127, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Jung, W.-S.; Hong, K.; Kim, Y.-Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Park, H.-Y. Effects of Moderate Combined Resistance- and Aerobic-Exercise for 12 Weeks on Body Composition, Cardiometabolic Risk Factors, Blood Pressure, Arterial Stiffness, and Physical Functions, among Obese Older Men: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endes, S.; Schaffner, E.; Caviezel, S.; Dratva, J.; Autenrieth, C.S.; Wanner, M.; Martin, B.; Stolz, D.; Pons, M.; Turk, A.; et al. Physical Activity Is Associated with Lower Arterial Stiffness in Older Adults: Results of the SAPALDIA 3 Cohort Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 31, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandercappellen, E.J.; Henry, R.M.A.; Savelberg, H.H.C.M.; Van Der Berg, J.D.; Reesink, K.D.; Schaper, N.C.; Eussen, S.J.P.M.; Van Dongen, M.C.J.M.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Schram, M.T.; et al. Association of the Amount and Pattern of Physical Activity With Arterial Stiffness: The Maastricht Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e017502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatelopoulos, K.; Tsoltos, N.; Armeni, E.; Paschou, S.A.; Augoulea, A.; Kaparos, G.; Rizos, D.; Karagouni, I.; Delialis, D.; Ioannou, S.; et al. Physical Activity Is Associated with Lower Arterial Stiffness in Normal-weight Postmenopausal Women. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2020, 22, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-F. Therapeutic Modification of Arterial Stiffness: An Update and Comprehensive Review. World J. Cardiol. 2015, 7, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, F.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Vollmer, W.M.; Appel, L.J.; Bray, G.A.; Harsha, D.; Obarzanek, E.; Conlin, P.R.; Miller, E.R.; Simons-Morton, D.G., 3rd; et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nagayama, D.; Saiki, A.; Shirai, K.; Tatsuno, I. Resveratrol Ameliorates Arterial Stiffness Assessed by Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. Heart J. 2017, 58, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janić, M.; Lunder, M.; Šabovič, M. Arterial Stiffness and Cardiovascular Therapy. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 621437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palić, B.; Brizić, I.; Sher, E.K.; Cvetković, I.; Džidić-Krivić, A.; Abdelghani, H.T.M.; Sher, F. Effects of Zofenopril on Arterial Stiffness in Hypertension Patients. Mol. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 3454–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, A.D.; Kim, W.; Park, S.H.; Park, J.S.; Cho, S.C.; Hong, S.B.; Hwang, S.H.; Kim, W. The effect of telmisartan on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with essential hypertension. Korean Circ. J. 2009, 39, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, A.; Feely, J. Beta-blockers reduce aortic stiffness in hypertension but nebivolol, not atenolol, reduces wave reflection. Am. J. Hypertens. 2008, 21, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Saiki, A.; Endo, K.; Ban, N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kawana, H.; Nagayama, D.; Ohhira, M.; Oyama, T.; Miyashita, Y.; et al. Protective effects of efonidipine, a T- and L-type calcium channel blocker, on renal function and arterial stiffness in type 2 diabetic patients with hypertension and nephropathy. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2009, 16, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huo, Y.; Wang, J.-G. Treatment Effect of Lacidipine and Amlodipine on Clinic and Ambulatory Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in a Randomized Double-Blind Trial. Blood Press. 2021, 30, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdis, A.; Ghiadoni, L.; Qasem, A.A.; Lorenzini, G.; Duranti, E.; Cartoni, G.; Bruno, R.M.; Bernini, G.; Taddei, S. Effect of Aliskiren Treatment on Endothelium-Dependent Vasodilation and Aortic Stiffness in Essential Hypertensive Patients. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, D.Z.I.; Scholey, J.W.; Jiang, S.; Har, R.; Lai, V.; Sochett, E.B.; Reich, H.N. The Effect of Direct Renin Inhibition Alone and in Combination with ACE Inhibition on Endothelial Function, Arterial Stiffness, and Renal Function in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2324–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topouchian, J.; Labat, C.; Gautier, S.; Bäck, M.; Achimastos, A.; Blacher, J.; Cwynar, M.; De La Sierra, A.; Pall, D.; Fantin, F.; et al. Effects of Metabolic Syndrome on Arterial Function in Different Age Groups: The Advanced Approach to Arterial Stiffness Study. J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayama, D.; Saiki, A.; Endo, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ban, N.; Kawana, H.; Ohira, M.; Oyama, T.; Miyashita, Y.; Shirai, K. Improvement of Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index by Glimepiride in Type 2 Diabetic Patients: Grimepiride Improves CAVI in Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 64, 1796–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjornstad, P.; Schäfer, M.; Truong, U.; Cree-Green, M.; Pyle, L.; Baumgartner, A.; Garcia Reyes, Y.; Maniatis, A.; Nayak, S.; Wadwa, R.P.; et al. Metformin Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Vascular Health in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation 2018, 138, 2895–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Ye, S. Effects of metformin on blood and urine pro-inflammatory mediators in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Inflamm. 2016, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambadiari, V.; Pavlidis, G.; Kousathana, F.; Varoudi, M.; Vlastos, D.; Maratou, E.; Georgiou, D.; Andreadou, I.; Parissis, J.; Triantafyllidi, H.; et al. Effects of 6-Month Treatment with the Glucagon like Peptide-1 Analogue Liraglutide on Arterial Stiffness, Left Ventricular Myocardial Deformation and Oxidative Stress in Subjects with Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonomidis, I.; Pavlidis, G.; Thymis, J.; Birba, D.; Kalogeris, A.; Kousathana, F.; Kountouri, A.; Balampanis, K.; Parissis, J.; Andreadou, I.; et al. Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists, Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors, and Their Combination on Endothelial Glycocalyx, Arterial Function, and Myocardial Work Index in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus After 12-Month Treatment. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, A.; Ott, C.; Jung, S.; Striepe, K.; Karg, M.V.; Kannenkeril, D.; Dienemann, T.; Schmieder, R.E. How Does Empagliflozin Improve Arterial Stiffness in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? Sub Analysis of a Clinical Trial. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherney, D.Z.; Perkins, B.A.; Soleymanlou, N.; Har, R.; Fagan, N.; Johansen, O.; Woerle, H.-J.; Von Eynatten, M.; Broedl, U.C. The Effect of Empagliflozin on Arterial Stiffness and Heart Rate Variability in Subjects with Uncomplicated Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neutel, C.H.G.; Wesley, C.D.; Van Praet, M.; Civati, C.; Roth, L.; De Meyer, G.R.Y.; Martinet, W.; Guns, P.J. Empagliflozin decreases ageing-associated arterial stiffening and vascular fibrosis under normoglycemic conditions. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2023, 152, 107212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, R.N.; Ramirez-Perez, F.I.; Cabral-Amador, F.J.; Morales-Quinones, M.; Foote, C.A.; Ghiarone, T.; Sharma, N.; Power, G.; Smith, J.A.; Rector, R.S.; et al. SGLT2 inhibition attenuates arterial dysfunction and decreases vascular F-actin content and expression of proteins associated with oxidative stress in aged mice. GeroScience 2022, 44, 1657–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.; Nikolic, D.; Patti, A.M.; Mannina, C.; Montalto, G.; McAdams, B.S.; Rizvi, A.A.; Cosentino, F. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Reduction of Cardiometabolic Risk: Potential Underlying Mechanisms. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 2814–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Farrokhi, F.R.; Abdalla, M.A.; Sathyapalan, T.; Banach, M.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. The Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Dipeptydilpeptidase-4 Inhibitors on Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Complications in Diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 6518221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampouloglou, P.K.; Bletsa, E.; Siasos, G.; Oikonomou, E.; Paschou, S.A.; Gouliopoulos, N.; Katsianos, E.; Tsigou, V.; Kassi, E.; Tentolouris, N.; et al. Differential effect of novel antidiabetic agents on the arterial stiffness and endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, ehab724.2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Wu, K.; Zhu, Y.-Z.; Bao, Z.-W. Roles and Mechanisms of Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitors in Vascular Aging. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 731273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, J.; Fu, M.; Dong, R.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Hu, S.; Li, W.; Xu, X.; Tu, L. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibition Improves Endothelial Senescence by Activating AMPK/SIRT1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 113951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoropoulou, P.; Tentolouris, A.; Eleftheriadou, I.; Tsilingiris, D.; Vlachopoulos, C.; Sykara, M.; Tentolouris, N. Effect of 12-Month Intervention with Low-Dose Atorvastatin on Pulse Wave Velocity in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes and Dyslipidaemia. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2019, 16, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorabi, A.; Kiaie, N.; Hajighasemi, S.; Banach, M.; Penson, P.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Statin-Induced Nitric Oxide Signaling: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidadi, M.; Montecucco, F.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. Beneficial Effect of Statin Therapy on Arterial Stiffness. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5548310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gepner, A.D.; Lazar, K.; Hulle, C.V.; Korcarz, C.E.; Asthana, S.; Carlsson, C.M. Effects of Simvastatin on Augmentation Index Are Transient: Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e009792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampi, M.C.; Faber, C.J.; Huynh, J.; Bordeleau, F.; Zanotelli, M.R.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Simvastatin Ameliorates Matrix Stiffness-Mediated Endothelial Monolayer Disruption. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaki, A.I.; Sarafidis, P.A.; Georgianos, P.I.; Kanavos, K.; Tziolas, I.M.; Zebekakis, P.E.; Lasaridis, A.N. Effects of Low-Dose Atorvastatin on Arterial Stiffness and Central Aortic Pressure Augmentation in Patients with Hypertension and Hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Hypertens. 2013, 26, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, C.; Ashley, D.T.; O’Sullivan, E.P.; McHenry, C.M.; Agha, A.; Thompson, C.J.; O’Gorman, D.J.; Smith, D. The Effects of Atorvastatin on Arterial Stiffness in Male Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 846807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, D.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Z. Improvement of Arterial Stiffness by Reducing Oxidative Stress Damage in Elderly Hypertensive Patients After 6 Months of Atorvastatin Therapy. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2012, 14, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiki, A.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ohira, M.; Nagayama, D.; Sato, N.; Kanayama, M.; Takahashi, M.; Shimizu, K.; Moroi, M.; et al. CAVI-Lowering Effect of Pitavastatin May Be Involved in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Subgroup Analysis of the TOHO-LIP. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2021, 28, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachopoulos, C. Combination Therapy in Hypertension: From Effect on Arterial Stiffness and Central Haemodynamics to Cardiovascular Benefits. Artery Res. 2016, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, F.; Liu, J.; Yang, G.-Y. Arterial Stiffness and Stroke: De-Stiffening Strategy, a Therapeutic Target for Stroke. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2017, 2, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujino, M.; Miura, S.; Kiya, Y.; Tominaga, Y.; Matsuo, Y.; Karnik, S.S.; Saku, K. A Small Difference in the Molecular Structure of Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers Induces AT1 Receptor-Dependent and -Independent Beneficial Effects. Hypertens. Res. 2010, 33, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Tian, E.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, C.; Yang, P.; Tian, K.; Liao, W.; Li, J.; Ren, C. Small Molecule Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors: A Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 968104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, L.; Castillo, J.; Quiñones, M.; Garcia-Vallvé, S.; Arola, L.; Pujadas, G.; Muguerza, B. Inhibition of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Activity by Flavonoids: Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Jahan, N.; Rahman, K.-; Sultana, B.; Jamil, S. Identification of Hypotensive Biofunctional Compounds of Coriandrum Sativum and Evaluation of Their Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibition Potential. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 4643736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrid, C.; Rocher, I.; Guery, O. Structure-Activity Relationships as a Response to the Pharmacological Differences in Beta- Receptor Ligands. Am. J. Hypertens. 1989, 2 Pt 2, 245S–251S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignarro, L.J. Different Pharmacological Properties of Two Enantiomers in a Unique Beta-Blocker, Nebivolol. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2008, 26, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.P.; Marche, P.; Hintze, T.H. Novel Vascular Biology of Third-Generation L-Type Calcium Channel Antagonists: Ancillary Actions of Amlodipine. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 2155–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.J. Aliskiren. Circulation 2008, 118, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanov, D.A.; Zou, J.; Babak, M.V. Biological Properties of Transition Metal Complexes with Metformin and Its Analogues. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lymperopoulos, A.; Borges, J.I.; Cora, N.; Sizova, A. Sympatholytic Mechanisms for the Beneficial Cardiovascular Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors: A Research Hypothesis for Dapagliflozin’s Effects in the Adrenal Gland. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faillie, J.-L. Pharmacological Aspects of the Safety of Gliflozins. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 118, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilsbøll, T. Liraglutide: A Once-Daily GLP-1 Analogue for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2007, 16, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, V.; Alam, O.; Siddiqui, N.; Jha, M.; Manaithiya, A.; Bawa, S.; Sharma, N.; Alshehri, S.; Alam, P.; Shakeel, F. Insight into Structure Activity Relationship of DPP-4 Inhibitors for Development of Antidiabetic Agents. Molecules 2023, 28, 5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, E.P.; Hohl, A.; de Melo, T.G.; Lauand, F. Linagliptin: Farmacology, Efficacy and Safety in Type 2 Diabetes Treatment. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2013, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Deplazes, E.; Cranfield, C.G.; Garcia, A. The Role of Structure and Biophysical Properties in the Pleiotropic Effects of Statins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, H.; Huang, B.; Zheng, C.; Peng, W.; Qin, L. Acanthopanax Senticosus: Review of Botany, Chemistry and Pharmacology. Pharmazie 2011, 66, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Nishida, M.; Saito, M.; Tanabe, A.; Eitsuka, T.; Yuan, S.H.; Ikekawa, N.; Nishida, H. The fruit of Acanthopanax senticosus (Rupr. et Maxim.) Harms improves insulin resistance and hepatic lipid accumulation by modulation of liver adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activity and lipogenic gene expression in high-fat diet-fed obese mice. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Lim, Y.; Shin, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Rhee, M.-Y.; Kwon, O. The Fruit of Acanthopanax Senticosus Harms Improves Arterial Stiffness and Blood Pressure: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2020, 14, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave Mehta, S.; Rathore, P.; Rai, G. Ginseng: Pharmacological Action and Phytochemistry Prospective. In Ginseng—Modern Aspects of the Famed Traditional Medicine; Hano, C., Chen, J.-T., Eds.; IntechOpen: London UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Yoon, J.; Lim, H.K.; Ryoo, S. Korean Red Ginseng Water Extract Restores Impaired Endothelial Function by Inhibiting Arginase Activity in Aged Mice. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 18, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, R.; Xiao, J.; Liu, X.; Dong, M.; Luan, X.; Ji, X.; Lu, H. Ginsenoside Rb1 Ameliorates Diabetic Arterial Stiffening via AMPK Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 753881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khayat, Z.; Hussein, J.; Ramzy, T.; Ashour, M. Antidiabetic Antioxidant Effect of Panax Ginseng. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 4616–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.-W.; Jiang, J.-L.; Zou, J.-J.; Yang, M.-Y.; Chen, F.-M.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Jia, L. Therapeutic Potential of Ginsenosides on Diabetes: From Hypoglycemic Mechanism to Clinical Trials. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 64, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Y.; Zaib, S.; Jannat, S.; Khan, I.; Rahman, M.M.; Park, S.K.; Chang, M.S. Inhibition of Aldose Reductase by Ginsenoside Derivatives via a Specific Structure Activity Relationship with Kinetics Mechanism and Molecular Docking Study. Molecules 2022, 27, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovski, E.; Jenkins, A.; Dias, A.G.; Peeva, V.; Sievenpiper, J.; Arnason, J.T.; Rahelic, D.; Josse, R.G.; Vuksan, V. Effects of Korean Red Ginseng (Panax Ginseng C.A. Mayer) and Its Isolated Ginsenosides and Polysaccharides on Arterial Stiffness in Healthy Individuals. Am. J. Hypertens. 2010, 23, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishtar, E.; Jovanovski, E.; Jenkins, A.; Vuksan, V. Effects of Korean White Ginseng (Panax Ginseng C.A. Meyer) on Vascular and Glycemic Health in Type 2 Diabetes: Results of a Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-controlled, Multiple-crossover, Acute Dose Escalation Trial. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2014, 3, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.-M.; Lim, J.-W.; Pyun, W.-B.; Kim, H.-Y. Korean Red Ginseng Improves Vascular Stiffness in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. J. Ginseng Res. 2010, 34, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucalo, I.; Jovanovski, E.; Rahelić, D.; Božikov, V.; Romić, Ž.; Vuksan, V. Effect of American Ginseng (Panax Quinquefolius L.) on Arterial Stiffness in Subjects with Type-2 Diabetes and Concomitant Hypertension. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 150, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murias, J.M.; Jiang, M.; Dzialoszynski, T.; Noble, E.G. Effects of Ginseng Supplementation and Endurance-Exercise in the Artery-Specific Vascular Responsiveness of Diabetic and Sedentary Rats. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, K.A.; Awad, E.M.; Nagy, M.A. Effects of panax quinquefolium on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: Role of C-peptide, nitric oxide and oxidative stress. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2011, 4, 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Qu, C.-Y.; Li, J.-X.; Wang, Y.-F.; Li, W.; Wang, C.-Z.; Wang, D.-S.; Song, J.; Sun, G.-Z.; Yuan, C.-S. Hypoglycemic and Hypolipidemic Effects of Malonyl Ginsenosides from American Ginseng (Panax Quinquefolius L.) on Type 2 Diabetic Mice. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 33652–33664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, S.S.; Lal, G.; Dubey, P.N.; Meena, M.D. Medicinal and Therapeutic Uses of Dill (Anethum Graveolens L.)—A Review. Int. J. Seed Spices 2019, 9, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fhayli, W.; Boëté, Q.; Kihal, N.; Cenizo, V.; Sommer, P.; Boyle, W.A.; Jacob, M.-P.; Faury, G. Dill Extract Induces Elastic Fiber Neosynthesis and Functional Improvement in the Ascending Aorta of Aged Mice with Reversal of Age-Dependent Cardiac Hypertrophy and Involvement of Lysyl Oxidase-Like-1. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N. Haematological and Hypoglycemic Potential Anethum Graveolens Seeds Extract in Normal and Diabetic Swiss Albino Mice. Vet. World 2013, 6, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Gautam, A.; Sharma, A.; Batra, A. Centella asiatica (L.): A plant with immense medicinal potential but threatened. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2010, 4, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hasimun, P.; Mulyani, Y.; Setiawan, A.R. Influences of Centella asiatica and Curcuma longa on arterial stiffness in a hypertensive animal model. Indones. J. Pharm. 2021, 32, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunaim, M.K.; Kamisah, Y.; Mohd Mustazil, M.N.; Fadhlullah Zuhair, J.S.; Juliana, A.H.; Muhammad, N. Centella Asiatica (L.) Urb. Prevents Hypertension and Protects the Heart in Chronic Nitric Oxide Deficiency Rat Model. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 742562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulyani, Y.; Hasimun, P.; Sukmawati, H. Effect of Nori, a Combination of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa) and Gotu Kola (Centella Asiatica) on Blood Pressure, Modulation of ACE, eNOS and iNOS Gene Expression in Hypertensive Rats. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 12, 2573–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A.U.; Samad, M.B.; D’Costa, N.M.; Akhter, F.; Ahmed, A.; Hannan, J. Anti-Hyperglycemic Activity of Centella Asiatica Is Partly Mediated by Carbohydrase Inhibition and Glucose-Fiber Binding. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, A.; Sahebkar, A.; Javadi, B. Melissa Officinalis L.—A Review of Its Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 188, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraj, S.; Rafieian-Kopaei; Kiani, S. Melissa Officinalis L: A Review Study with an Antioxidant Prospective. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalikova, D.; Tyukos Kaprinay, B.; Brnoliakova, Z.; Sasvariova, M.; Krenek, P.; Babiak, E.; Frimmel, K.; Bittner Fialova, S.; Stankovicova, T.; Sotnikova, R.; et al. Impact of Improving Eating Habits and Rosmarinic Acid Supplementation on Rat Vascular and Neuronal System in the Metabolic Syndrome Model. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yui, S.; Fujiwara, S.; Harada, K.; Motoike-Hamura, M.; Sakai, M.; Matsubara, S.; Miyazaki, K. Beneficial Effects of Lemon Balm Leaf Extract on In Vitro Glycation of Proteins, Arterial Stiffness, and Skin Elasticity in Healthy Adults. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2017, 63, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Liu, P. Salvia miltiorrhiza Burge (Danshen): A Golden Herbal Medicine in Cardiovascular Therapeutics. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 802–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, Q.; Ning, J.; Chen, H.; An, S. Aqueous extract of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge reduces blood pressure through inhibiting oxidative stress, inflammation and fibrosis of adventitia in primary hypertension. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1093669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wei, L.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Physiological fluid shear stress synergistically enhances the protective effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza extract on endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 43907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Wang, P.; Xu, S.; Xu, W.; Xu, W.; Chu, K.; Lu, J. Biological Activities of Salvianolic Acid B from Salvia Miltiorrhiza on Type 2 Diabetes Induced by High-Fat Diet and Streptozotocin. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-F.; Tung, K.; Chou, C.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Lin, J.-G.; Tanaka, H. Panax Ginseng and Salvia Miltiorrhiza Supplementation Abolishes Eccentric Exercise-Induced Vascular Stiffening: A Double-Blind Randomized Control Trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudu, C.K.; Dutta, T.; Ghorai, M.; Biswas, P.; Samanta, D.; Oleksak, P.; Jha, N.K.; Kumar, M.; Radha; Proćków, J.; et al. Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicology of Garlic (Allium Sativum), a Storehouse of Diverse Phytochemicals: A Review of Research from the Last Decade Focusing on Health and Nutritional Implications. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 949554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasimun, P.; Mulyani, Y.; Rehulina, E.; Zakaria, H. Impact of Black Garlic on Biomarkers of Arterial Stiffness and Frontal QRS-T Angle on Hypertensive Animal Model. J. Young Pharm. 2020, 12, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, O.S.; Komolafe, A.O.; Ogunlade, O.; Olayode, A.A.; Akinjisola, A.A. Aqueous Extract of Garlic (Allium Sativum) Administration Alleviates High Salt Diet-Induced Changes in the Aorta of Adult Wistar Rats: A Morphological and Morphometric Study. Anatomy 2016, 10, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Turner, B.; Mølgaard, C.; Marckmann, P. Effect of Garlic (Allium Sativum) Powder Tablets on Serum Lipids, Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Normo-Lipidaemic Volunteers: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruenwald, J.; Bongartz, U.; Bothe, G.; Uebelhack, R. Effects of Aged Garlic Extract on Arterial Elasticity in a Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial Using EndoPATTM Technology. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 19, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt-Grögler, K.; Ling, M.; Boudoulas, H.; Belz, G.G. Protective Effect of Chronic Garlic Intake on Elastic Properties of Aorta in the Elderly. Circulation 1997, 96, 2649–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopade, V.V.; Phatak, A.A.; Upaganlawar, A.B.; Tankar, A.A. Phcog Rev.:Plant Review Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis): Chemistry, Traditional, Medicinal Uses and Its Pharmacological Activities—A Review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2008, 2, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Szulińska, M.; Stępień, M.; Kręgielska-Narożna, M.; Suliburska, J.; Skrypnik, D.; Bąk-Sosnowska, M.; Kujawska-Łuczak, M.; Grzymisławska, M.; Bogdański, P. Effects of green tea supplementation on inflammation markers, antioxidant status and blood pressure in NaCl-induced hypertensive rat model. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1295525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-H.; Yang, Y.-C.; Wu, J.-S.; Huang, Y.-H.; Lee, C.-T.; Lu, F.-H.; Chang, C.-J. Increased Tea Consumption Is Associated with Decreased Arterial Stiffness in a Chinese Population. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quezada-Fernández, P.; Trujillo-Quiros, J.; Pascoe-González, S.; Trujillo-Rangel, W.A.; Cardona-Müller, D.; Ramos-Becerra, C.G.; Barocio-Pantoja, M.; Rodríguez-de La Cerda, M.; Nérida Sánchez-Rodríguez, E.; Cardona-Muñóz, E.G.; et al. Effect of Green Tea Extract on Arterial Stiffness, Lipid Profile and sRAGE in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, G.; Debjit, B.; Duraivel, S.; Harish, G. Traditional and Medicinal Uses of Carica papaya. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2013, 1, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hasimun, P.; Sulaeman, A.; Maharani, I.D.P. Supplementation of Carica Papaya Leaves (Carica Papaya L.) in Nori Preparation Reduced Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness on Hypertensive Animal Model. J. Young Pharm. 2020, 12, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; Díaz-Zagoya, J.C.; Ble-Castillo, J.L.; Miranda-Osorio, P.H.; Castell-Rodríguez, A.E.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A.; Aguilar-Mariscal, H.; Ramón-Frías, T.; Bermúdez-Ocaña, D.Y. Hypoglycemic Effect of Carica papaya Leaves in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, G.; Ronchi, S.; Do Nascimento, A.; De Lima, E.; Romão, W.; Da Costa, H.; Scherer, R.; Ventura, J.; Lenz, D.; Bissoli, N.; et al. Antihypertensive Effect of Carica papaya Via a Reduction in ACE Activity and Improved Baroreflex. Planta Med. 2014, 80, 1580–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, A.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Perkins-Veazie, P.M.; Arjmandi, B.H. Effects of Watermelon Supplementation on Aortic Blood Pressure and Wave Reflection in Individuals with Prehypertension: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2011, 24, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Wong, A.; Arjmandi, B.H. Watermelon Extract Supplementation Reduces Ankle Blood Pressure and Carotid Augmentation Index in Obese Adults with Prehypertension or Hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2012, 25, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Wong, A.; Kalfon, R. Effects of Watermelon Supplementation on Aortic Hemodynamic Responses to the Cold Pressor Test in Obese Hypertensive Adults. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 27, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Wong, A.; Hooshmand, S.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A. Effects of Watermelon Supplementation on Arterial Stiffness and Wave Reflection Amplitude in Postmenopausal Women. Menopause 2013, 20, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Alvarez-Alvarado, S.; Jaime, S.J.; Kalfon, R. L-Citrulline Supplementation Attenuates Blood Pressure, Wave Reflection and Arterial Stiffness Responses to Metaboreflex and Cold Stress in Overweight Men. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujie, S.; Iemitsu, K.; Inoue, K.; Ogawa, T.; Nakashima, A.; Suzuki, K.; Iemitsu, M. Wild Watermelon-Extracted Juice Ingestion Reduces Peripheral Arterial Stiffness with an Increase in Nitric Oxide Production: A Randomized Crossover Pilot Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussmann, R.W.; Paniagua Zambrana, N.Y.; Romero, C.; Hart, R.E. Astonishing Diversity—The Medicinal Plant Markets of Bogotá, Colombia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patonah, H.; Agus, S.; Arif, H.; Yani, M. Effect of Curcuma Longa L. Extract on Noninvasive Cardiovascular Biomarkers in Hypertension Animal Models. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 11, 085–089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleenor, B.S.; Sindler, A.L.; Marvi, N.K.; Howell, K.L.; Zigler, M.L.; Yoshizawa, M.; Seals, D.R. Curcumin Ameliorates Arterial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress with Aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, S.A.; Arya, M.; Momin, S.A. Structure Activity Relationship of Tautomers of Curcumin: A Review. Ukr. Food J. 2019, 8, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakmareong, S.; Kukongviriyapan, U.; Pakdeechote, P.; Kukongviriyapan, V.; Kongyingyoes, B.; Donpunha, W.; Prachaney, P.; Phisalaphong, C. Tetrahydrocurcumin Alleviates Hypertension, Aortic Stiffening and Oxidative Stress in Rats with Nitric Oxide Deficiency. Hypertens. Res. 2012, 35, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangartit, W.; Kukongviriyapan, U.; Donpunha, W.; Pakdeechote, P.; Kukongviriyapan, V.; Surawattanawan, P.; Greenwald, S.E. Tetrahydrocurcumin Protects against Cadmium-Induced Hypertension, Raised Arterial Stiffness and Vascular Remodeling in Mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, M.; Mimaki, Y.; Nishiyama, T.; Mae, T.; Kishida, H.; Tsukagawa, M.; Takahashi, K.; Kawada, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Kitahara, M. Hypoglycemic Effects of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa L. Rhizomes) on Genetically Diabetic KK-Ay Mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 937–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, A.; Selvarajan, S.; Kamalanathan, S.; Kadhiravan, T.; Prasanna Lakshmi, N.C.; Adithan, S. Effect of Curcuma longa on Vascular Function in Native Tamilians with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized, Double-blind, Parallel Arm, Placebo-controlled Trial. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1898–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-A.; Su, B.-N.; Keller, W.J.; Mehta, R.G.; Kinghorn, A.D. Antioxidant Xanthones from the Pericarp of Garcinia Mangostana (Mangosteen). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2077–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wihastuti, T.A.; Aini, F.N.; Tjahjono, C.T.; Heriansyah, T. Dietary Ethanolic Extract of Mangosteen Pericarp Reduces VCAM-1, Perivascular Adipose Tissue and Aortic Intimal Medial Thickness in Hypercholesterolemic Rat Model. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 3158–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonprom, P.; Boonla, O.; Chayaburakul, K.; Welbat, J.U.; Pannangpetch, P.; Kukongviriyapan, U.; Kukongviriyapan, V.; Pakdeechote, P.; Prachaney, P. Garcinia mangostana Pericarp Extract Protects against Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Remodeling via Suppression of P47 Phox and iNOS in Nitric Oxide Deficient Rats. Ann. Anat. Anat. Anz. 2017, 212, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, A.A.; Budiman, J.; Prasetyo, A. Anti-Inflammatory Potency of Mangosteen (Garcinia Mangostana L.): A Systematic Review. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jittiporn, K.; Samer, J.; Thitiwuthikiat, P. Þ-Mangostin Protects Endothelial Cell against H2O2-Induced Senescence via P38/Sirt1/MnSOD Pathway. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 14, 091–097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maejima, K.; Ohno, R.; Nagai, R.; Nakata, S. Effect of mangosteen pericarp extract on skin moisture and arterial stiffness: Placebo-controlled double-blinded randomized clinical trial. Glycative Stress Res. 2018, 5, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Anand Swarup Kolla, R.L.; Sattar, M.; Abdullah, N.; Abdulla, M.; Salman, I.; Rathore, H.; Johns, E. Effect of Dragon Fruit Extract on Oxidative Stress and Aortic Stiffness in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in Rats. Pharmacogn. Res. 2010, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheok, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Caton, P.W.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. Betalain-Rich Dragon Fruit (Pitaya) Consumption Improves Vascular Function in Men and Women: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Crossover Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1418–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wahaibi, A.; Nazaimoon, W.M.W.; Norsyam, W.N.; Farihah, H.S.; Azian, A.L. Effect of Water Extract of Labisia Pumila Var Alata on Aorta of Ovariectomized Sprague Dawley Rats. Pak. J. Nutr. 2008, 7, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mansor, F.; Gu, H.F.; Östenson, C.-G.; Mannerås-Holm, L.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Wan Mohamud, W.N. Labisia Pumila Upregulates Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Expression in Rat Adipose Tissues and 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 2013, 808914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.; Chermahini, S.H.; Suan, C.L.; Sarmidi, M.R. Labisia Pumila: A Review on Its Traditional, Phytochemical and Biological Uses. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 27, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, H. The Vascular Effects of Isolated Isoflavones—A Focus on the Determinants of Blood Pressure Regulation. Biology 2021, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Khairul Nizam Mazlan, M.; Firdaus Abdul Aziz, A.; Mohd Gazzali, A.; Amir Rawa, M.S.; Wahab, H.A. Phaleria Macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl.: An Updated Review of Pharmacological Effects, Toxicity Studies, and Separation Techniques. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, R.; Umar, M.; Asmawi, M.; Sadikun, A.; Dewa, A.; Manshor, N.; Razali, N.; Syed, H.; Ahamed Basheer, M. Polar Components of Phaleria Macrocarpa Fruit Exert Antihypertensive and Vasorelaxant Effects by Inhibiting Arterial Tone and Extracellular Calcium Influx. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2018, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, D.; Badruzzaman, N.; Sidik, N.; Tawang, A. Phaleria Macrocarpa Fruits Methanolic Extract Reduces Blood Pressure and Blood Glucose in Spontaneous Hypertensive Rats (SHR). J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rizal, M.F.; Haryanto, J.; Has, E.M.M. The effect of Phaleria macrocarpa ethnic food complementary to decrease blood pressure. J. Vocat. Nurs. 2020, 1, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasaroju, S.; Gottumukkala, K.M.O. Current Trends in the Research of Emblica officinalis (Amla): A Pharmacological Perspective. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2014, 24, 150–159. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, B.S.; Kanthe, P.S.; Reddy, C.R.; Das, K.K. Emblica Officinalis (Amla) Ameliorates High-Fat Diet-Induced Alteration of Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 17, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, P.; Vijayakumar, S.; Kothandaraman, S.; Palani, M. Anti-diabetic activity of quercetin extracted from Phyllanthus emblica L. fruit: In silico and in vivo approaches. J. Pharm. Anal. 2018, 8, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, U.; Fatima, N.; Pilli, R. Evaluation of Phyllanthus Emblica Extract on Cold Pressor Induced Cardiovascular Changes in Healthy Human Subjects. Pharmacogn. Res. 2014, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usharani, P.; Merugu, P.L.; Nutalapati, C. Evaluation of the Effects of a Standardized Aqueous Extract of Phyllanthus Emblica Fruits on Endothelial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, Systemic Inflammation and Lipid Profile in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomised, Double Blind, Placebo Controlled Clinical Study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, J.P. Quelques plantes employées dans le nord de Madagascar: Monographies. In Plantes médicinales du Nord de Madagascar: Ethnobotanique Antakarana et informations scientifiques, 1st ed.; Jardin du Monde: Basparts, France, 2012; pp. 176–177. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, G.C.; Baiyeri, K.P.; Akinnnagbe, O. Ethno-medicinal and culinary uses of Moringa oleifera Lam. in Nigeria. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 799–804. [Google Scholar]

- Aekthammarat, D.; Tangsucharit, P.; Pannangpetch, P.; Sriwantana, T.; Sibmooh, N. Moringa oleifera leaf extract enhances endothelial nitric oxide production leading to relaxation of resistance artery and lowering of arterial blood pressure. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randriamboavonjy, J.I.; Rio, M.; Pacaud, P.; Loirand, G.; Tesse, A. Moringa oleifera Seeds Attenuate Vascular Oxidative and Nitrosative Stresses in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 4129459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randriamboavonjy, J.I.; Heurtebise, S.; Pacaud, P.; Loirand, G.; Tesse, A. Moringa oleifera Seeds Improve Aging-Related Endothelial Dysfunction in Wistar Rats. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 2567198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, A.; Yao, L.; Toque, H.A.; Shatanawi, A.; Xu, Z.; Caldwell, R.B.; Caldwell, R.W. Angiotensin II-induced arterial thickening, fibrosis and stiffening involves elevated arginase function. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Machin, D.R.; Auduong, Y.; Gogulamudi, V.R.; Liu, Y.; Islam, M.T.; Lesniewski, L.A.; Donato, A.J. Lifelong SIRT-1 overexpression attenuates large artery stiffening with advancing age. Aging 2020, 12, 11314–11324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, V.; Randriamboavonjy, J.I.; Rafatro, H.; Manzo, V.; Dal Col, J.; Filippelli, A.; Corbi, G.; Tesse, A. SIRT1 Signaling Is Involved in the Vascular Improvement Induced by Moringa Oleifera Seeds during Aging. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Malki, A.L.; El Rabey, H.A. The antidiabetic effect of low doses of Moringa oleifera Lam. seeds on streptozotocin-induced diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in male rats. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 381040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randriamboavonjy, J.I.; Loirand, G.; Vaillant, N.; Lauzier, B.; Derbré, S.; Michalet, S.; Pacaud, P.; Tesse, A. Cardiac Protective Effects of Moringa oleifera Seeds in Spontaneous Hypertensive Rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 2016, 29, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyeleye, I.S.; Ogunsuyi, O.B.; Oluokun, O.O.; Oboh, G. Seeds of moringa (Moringa oleifera) and mucuna (Mucuna pruriens L.) modulate biochemical indices of L-NAME-induced hypertension in rats: A comparative study. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbrod, R.M.; Shiang, T.; Al Sayah, L.; Fry, J.L.; Bajpai, S.; Reinhart-King, C.A.; Lob, H.E.; Santhanam, L.; Mitchell, G.; Cohen, R.A.; et al. Arterial stiffening precedes systolic hypertension in diet-induced obesity. Hypertension 2013, 62, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Lastra, G.; Manrique, C.; Jia, G.; Aroor, A.R.; Hayden, M.R.; Barron, B.J.; Niles, B.; Padilla, J.; Sowers, J.R. Xanthine oxidase inhibition protects against Western diet-induced aortic stiffness and impaired vasorelaxation in female mice. Am. J. Physiol. 2017, 313, R67–R77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost, G.; Bulckaen, H.; Gaxatte, C.; Boulanger, E.; Béraud, G.; Creusy, C.; Puisieux, F.; Fontaine, P. Structural modifications in the arterial wall during physiological aging and as a result of diabetes mellitus in a mouse model: Are the changes comparable? Diabetes Metab. 2011, 37, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyon, M.; Mathieu, P.; Moreau, P. Decreased expression of γ-carboxylase in diabetes-associated arterial stiffness: Impact on matrix Gla protein. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 97, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Plant Name | Preclinical Studies (Cell and/or Animal Models) |

|---|---|

| Acanthopanax senticosus (Rupr. and Maxim) | HFD-induced obese C57BL/6J mice |

| Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer | Aged C57BL/6J mice; VSMC; STZ-induced diabetes in rats |

| Panax quinquefolius L. | STZ-induced diabetes in mice and rats |

| Anethum graveolens L. | Aged C57BL/6J mice; Alloxan-induced diabetes in mice |

| Centella asiatica (L). Urb. | HFFD-induced hypertensive rats; SHR; L-NAME-induced hypertensive Sprague–Dawley or Wistar rats; STZ-induced diabetes in rats |

| Melissa officinalis L. | HFFD-induced metabolic syndrome in rats; In vitro collagen and elastin fibre sheets; Glycation-induced collagen colouration in vitro model |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge | SHR; Wistar Kyoto rats; in vitro endothelial cells; STZ-induced diabetes in rats |

| Allium sativum L. | HFFD-induced hypertension in Wistar rats; (NaCl 8%)-induced aortic remodelling in rats |

| Camellia sinensis L. (Kuntze) | NaCl-induced hypertensive Wistar rat model |

| Carica papaya L. | HFFD-induced hypertensive rats; STZ-induced diabetes in rats; SHR |

| Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | - |

| Curcuma longa L. | HFFD-induced hypertension in rats; Aged C57BL/6N mice; L-NAME hypertensive rats; cadmium-induced aortic damage in rats; cadmium-induced aortic damage with hypertension and oxidative stress; diabetic KK-Ay/T mice |

| Garcinia mangostana L. | Hypercholesterolemic rats; L-NAME hypertensive rats; H2O2-induced senescence in endothelial cells |

| Hylocereus undatus (Haw.) Britton et Rose | STZ-induced diabetes in Sprague–Dawley rats |

| Labisia pumila (Blume) Fern. -Vill. Var Alata | OVX female rats; Rats with polycystic ovary syndrome |

| Phaleria macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl. | SHR and Wistar Kyoto rats |

| Phyllantus emblica L. | HFD rat model; STZ-induced diabetes in rats |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | L-NAME-induced hypertensive rats; SHR; Middle-aged Wistar rats |

| Plant Name | Clinical Trials Yes/No | Pathology or Health Status of the Enrolled Subjects | Number of Subjects | Gender of the Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthopanax senticosus (Rupr. et Maxim) harms | Yes | Hypertensive and metabolic Disorder; Smokers | 76 | ♂ |

| Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer | Yes | Healthy humans Type 2 diabetes subjects Stable angina with coronary artery stenosis | 17 25 20 | ♂ and ♀ ♂ and ♀ ♂ |

| Panax quinquefolius L. | Yes | Hypertension and type 2 diabetes | 64 | ♂ and ♀ |

| Anethum graveolens L. | No | - | - | - |

| Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. | No | - | - | - |

| Melissa officinalis L. | Yes | Healthy subjects | 28 | ♂ and ♀ |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge | Yes | Healthy young subjects (eccentric exercise) | 24 | ♂ |

| Allium sativum L. | Yes | Healthy normolipidemic humans Healthy middle-aged or grade 1 hypertensive patients Healthy elderly humans | 75 57 101 | ♂ and ♀ ♂ and ♀ ♂ and ♀ |

| Camellia sinensis L. (Kuntze) | Yes | Healthy Chinese subjects Type 2 diabetes patients | 3135 20 | ♂ and ♀ ♂ |

| Carica papaya L. | No | - | - | - |

| Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | Yes | Prehypertension Prehypertension and hypertension Middle-aged obese patients with hypertension Postmenopausal women Obese male with hypertension Healthy young subjects | 9 14 13 12 16 12 | ♂ and ♀ ♂ and ♀ ♂ and ♀ ♀ ♂ ♀ |

| Curcuma longa L. | Yes | Type 2 diabetes patients | 114 | ♂ and ♀ |

| Garcinia mangostana L. | Yes | Healthy subjects | 40 | ♀ |

| Hylocereus undatus (Haw.) Britton et Rose | Yes | Healthy subjects | 18 | ♂ and ♀ |

| Labisia pumila (Blume) Fern. -Vill. Var Alata | No | - | - | - |

| Phaleria macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl. | Yes | Elderly hypertensive patients | 40 | ♂ and ♀ |

| Phyllantus emblica L. | Yes | Healthy human subjects subjected to cold pressor test Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and lipid profile in subjects with metabolic syndrome | 15 59 | ♂ ♂ and ♀. |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | No | - | - | - |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Araliaceae |  | Acanthopanax senticosus (Rupr. et Maxim) Harms | Reduction of vascular stiffness (decrease in PWV and SBP values); improvement of vasodilation associated with eNOS/NO production; antihyperglycemic and antioxidant properties. |

| Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer | Vasodilation activity (reduction in arginase, enhanced eNOS/NO production); reduction of vascular rigidity due to ageing; antihyperglycemic and antioxidant properties. | |

| Panax quinquefolius L. | AS reduction; arterial relaxation enhancement and antihypertensive property; reduced blood glucose, TG, cholesterol, and insulin resistance. | |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apiaceae |  | Anethum graveolens L. | Decrease in SBP and DBP; increase in aortic distensibility and improved endothelial function; reduced elastin degradation and improved elastic fibre neo-synthesis. |

| Centella asiatica (L). Urb | Reduction in BP and PWV; enhanced eNOS/NO production and increased vasorelaxation. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. | |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lamiaceae |  | Melissa officinalis L. | Improved cardiac function; antioxidant properties (reduced AGEs); decreased BP and PWV; increased endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation. |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge | Reduced PWV, inflammation, and oxidative stress; decreased glucose and cholesterol; increased insulin sensitivity. | |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amaryllidaceae |  | Allium sativum L. | Decreased PWV, BP, DBP, and AIx; AS reduction (reduced tunica media/adventitia/intima wall thickness); antihyperglycemic and antihypertensive activities; increased aortic elasticity; decreased blood TG. |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theaceae |  | Camellia sinensis L. (Kuntze) | PWV decrease; oxidative stress and AS prevention; interaction with catecholamine signalling; endothelial function improvement; inhibition of extracellular matrix modifications. |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caricaceae |  | Carica papaya L. | Antihyperglycemic and antihypertensive effects; anti-ACE effects; stabilisation of BP; anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties; increased NO production. |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cucurbutaceae |  | Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | Decrease in BP, AIx and PWV; vacular function improvement; increased NO production and vasodilation; enhanced antioxidant defence (SOD and GSH increased expressions). |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zingiberaceae |  | Curcuma longa L. | Decreased BP and PWV; increased eNOS-associated vasodilation and SOD2 expression; downregulation of NOX2 subunit p67phox; reversed ageing-induced AS and increased aortic elasticity; free radical scavenging; decreases in MMP-2, MMP-9, and AGEs; reduced blood glucose and increased insulin sensitization. |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clusiaceae |  | Garcinia mangostana L. | Reduced AS, AVI, and API; amplified aortic vasodilation; inhibition of vascular AGE formation; reduced Hb1Ac, total cholesterol, and LDL-C; reduced VCAM-1 expression; antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties; inhibition of the ACE enzyme, RAAS, and SGLT-2. |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cactaceae |  | Hylocereus undatus (Haw.) Britton et Rose | Reduction in SBP, PWV, and AIx; MDA enzyme activity decrease and antioxidant defence amelioration (increased SOD and TAC); increased NO production and FMD; antidiabetic and antihypertensive properties (inhibition of SGLT-2 and/or GLP-1 RAs and/or DPP-4); inhibition of inflammatory cell proliferation/migration-induced aortic thickness. |

| Family | Name of the Plant | Effects of the Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|