Translational Potential: Kidney Tubuloids in Precision Medicine and Regenerative Nephrology

Abstract

1. Introduction

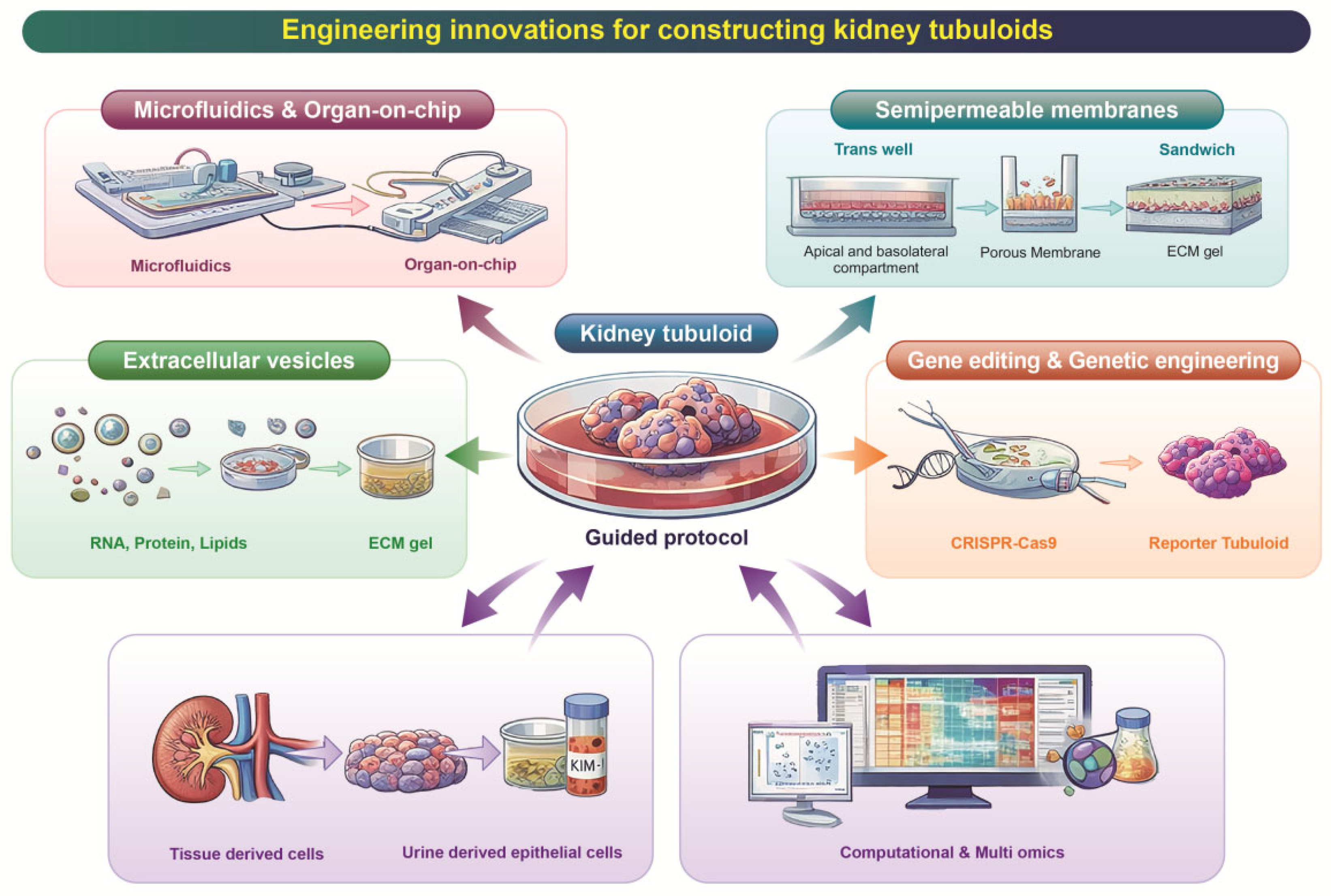

2. Biological and Technological Foundations of Tubuloid Systems

3. Recent Engineering Innovations for Constructing Tubuloids

3.1. Microfluidics and Organ-on-Chip Integration

3.2. Semipermeable Membrane/“Sandwich” Culture Formats

3.3. Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Maturation

3.4. Gene Editing and Genetic Engineering

3.5. Integrative Approaches: Computational & Multi-Omics

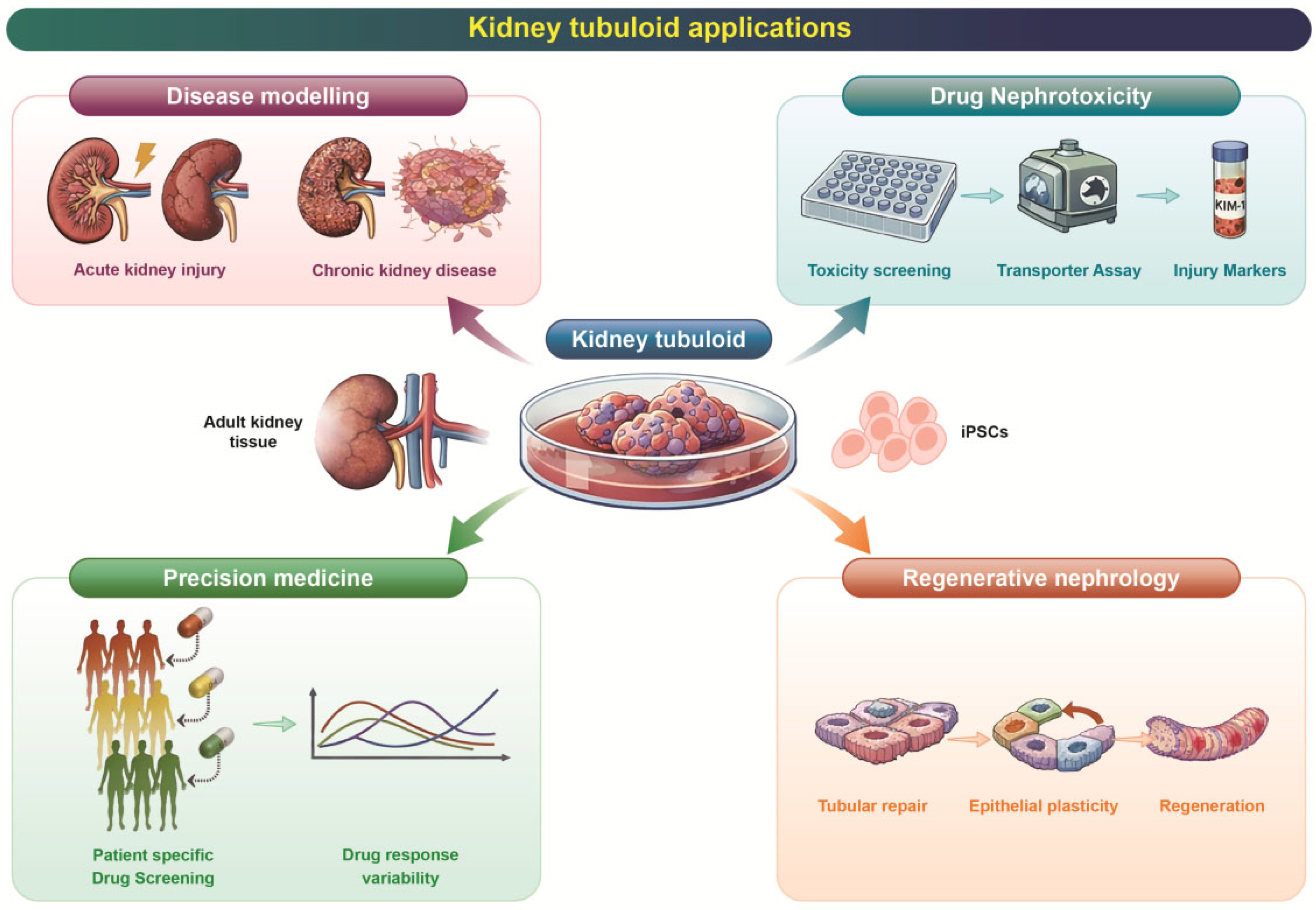

4. Applications in Precision Medicine

4.1. Patient-Derived Disease Modeling

4.2. Toward Regenerative Nephrology

4.3. Modeling Complex Pathophysiology

4.4. Biobanks for Precision Testing

4.5. Bioartificial Kidney Engineering

5. Challenges & Considerations for Clinical Translation

5.1. Incomplete Functional Maturation and Segmental Representation

5.2. Model Complexity

5.3. Technical and Scalability Challenges

5.4. Translational and Regulatory Considerations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SGLT2 | Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 |

| OCT2 | Organic cation transporter 2 |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| MRP2 | Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 |

| KIM-1 | Kidney injury molecule-1 |

| LTL | Lotus tetragonolobus lectin |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| NPHS1 | Nephrin-1 |

| WT1 | Wilms’ tumor 1 |

| NGAL | Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. |

| CLU | Clusterin |

| SPP1 | Secreted Phosphoprotein 1/Osteopontin |

| ZO-1 | Zonula occludens-1. |

| Na+/K+-ATPase | Sodium-potassium-exchanging adenosine triphosphatase |

| AQP1 | Aquaporin-1 |

| OAT1/3 | Organic anion transporter-1/3 |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| BMP7 | Bone morphogenetic protein 7 |

| miR-200 | microRNA-200 |

| PKD1/2 | Polycystic kidney disease 1/2 |

| SLC12A1/3 | Solute carrier family 12-member 1/3 (Na-K-Cl cotransporter) |

| CLCNKB | Chloride channel, kidney, B |

| VUS | Variants of uncertain significance |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. |

| HSP70 | Heat shock protein 70 |

| CD24+ | Cluster of differentiation 24 positive cell |

| γH2AX | Gamma H2A histone family member X. |

| p16 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

| P21 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A |

| NHE3, | Sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3 |

| MATE1 | Multidrug and toxin extrusion protein 1 |

References

- Yousef Yengej, F.A.; Jansen, J.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Verhaar, M.C.; Clevers, H. Kidney organoids and tubuloids. Cells 2020, 9, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindoso, R.S.; Yousef Yengej, F.A.; Voellmy, F.; Altelaar, M.; Mancheño Juncosa, E.; Tsikari, T.; Ammerlaan, C.M.; Van Balkom, B.W.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Verhaar, M.C. Differentiated kidney tubular cell-derived extracellular vesicles enhance maturation of tubuloids. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yengej, F.A.Y.; Casellas, C.P.; Ammerlaan, C.M.; Hanhof, C.J.O.; Dilmen, E.; Beumer, J.; Begthel, H.; Meeder, E.M.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Rookmaaker, M.B. Tubuloid differentiation to model the human distal nephron and collecting duct in health and disease. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevalier, R.L. The proximal tubule is the primary target of injury and progression of kidney disease: Role of the glomerulotubular junction. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2016, 311, F145–F161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.J.; Chapron, A.; Chapron, B.D.; Voellinger, J.L.; Lidberg, K.A.; Yeung, C.K.; Wang, Z.; Yamaura, Y.; Hailey, D.W.; Neumann, T. Development of a microphysiological model of human kidney proximal tubule function. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutgens, F.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Margaritis, T.; Rios, A.; Ammerlaan, C.; Jansen, J.; Gijzen, L.; Vormann, M.; Vonk, A.; Viveen, M. Tubuloids derived from human adult kidney and urine for personalized disease modeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef Yengej, F.A.; Jansen, J.; Ammerlaan, C.M.; Dilmen, E.; Pou Casellas, C.; Masereeuw, R.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Smeets, B.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Verhaar, M.C. Tubuloid culture enables long-term expansion of functional human kidney tubule epithelium from iPSC-derived organoids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2216836120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutgens, F.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Verhaar, M.C. A perspective on a urine-derived kidney tubuloid biobank from patients with hereditary tubulopathies. Tissue Eng. 2021, 27, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannuzzi, F.; Picerno, A.; Maiullari, S.; Montenegro, F.; Cicirelli, A.; Stasi, A.; De Palma, G.; Di Lorenzo, V.F.; Pertosa, G.B.; Pontrelli, P. Unveiling spontaneous renal tubule-like structures from human adult renal progenitor cell spheroids derived from urine. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2025, 14, szaf002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Nescolarde, A.B.; Santos, L.L.; Kong, L.; Ekinci, E.; Moore, P.; Dimitriadis, E.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J.; Combes, A.N. Comparative Analysis of Human Kidney Organoid and Tubuloid Models. Kidney360 2025, 6, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virumbrales-Muñoz, M.; Ayuso, J.M.; Gong, M.M.; Humayun, M.; Livingston, M.K.; Lugo-Cintrón, K.M.; McMinn, P.; Álvarez-García, Y.R.; Beebe, D.J. Microfluidic lumen-based systems for advancing tubular organ modeling. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6402–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, J.-B.; Kim, K.; Sung, G.Y. Effect of shear stress on the proximal tubule-on-a-chip for multi-organ microphysiological system. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 115, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakeman, P.; Miao, S.; Cheng, J.; Lee, C.-Z.; Roy, S.; Fissell, W.H.; Ferrell, N. A modular microfluidic bioreactor with improved throughput for evaluation of polarized renal epithelial cells. Biomicrofluidics 2016, 10, 064106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Mahler, G.J. A glomerulus and proximal tubule microphysiological system simulating renal filtration, reabsorption, secretion, and toxicity. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Q.; Fardous, R.S.; Hazaymeh, R.; Alshmmari, S.; Zourob, M. Pharmacokinetics-on-a-chip: In vitro microphysiological models for emulating of drugs ADME. Adv. Biol. 2021, 5, 2100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ness, K.P.; Cesar, F.; Yeung, C.K.; Himmelfarb, J.; Kelly, E.J. Microphysiological systems in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination sciences. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022, 15, 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomatto, M.A.; Gai, C.; Bussolati, B.; Camussi, G. Extracellular vesicles in renal pathophysiology. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalliston, T.W.M. Development of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Derived Kidney Organoids for Disease Modelling of Diabetic Nephropathy with Chemical Mediators and CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing; UCL (University College London): London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Traitteur, T.; Zhang, C.; Morizane, R. The application of iPSC-derived kidney organoids and genome editing in kidney disease modeling. PSCs-State Sci. 2022, 16, 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, I.; Faucher, Q.; Bernard, J.-S.; Giunchi, P.; Humeau, A.; Sauvage, F.-L.; Marquet, P.; Védrenne, N.; Di Meo, F. Proximal tubule-on-chip as a model for predicting cation transport and drug transporter dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.X.; Youhanna, S.; Zandi Shafagh, R.; Kele, J.; Lauschke, V.M. Organotypic and microphysiological models of liver, gut, and kidney for studies of drug metabolism, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 33, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves, J.O.; Heja, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Robinson, S.S.; Miyoshi, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Schäffers, O.J.; Morizane, R.; Lewis, J.A. 3D proximal tubule-on-chip model derived from kidney organoids with improved drug uptake. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapin, B.; Vandensteen, J.; Gropplero, G.; Mazloum, M.; Bienaimé, F.; Descroix, S.; Coscoy, S. Decoupling shear stress and pressure effects in the biomechanics of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease using a perfused kidney-on-chip. Acta Biomater. 2025, 197, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, O.Y.; Villenave, R.; Cronce, M.J.; Leineweber, W.D.; Benz, M.A.; Ingber, D.E. Organs-on-chips with integrated electrodes for trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements of human epithelial barrier function. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas, A.; Schavemaker, F.; Kosim, K.; Kurek, D.; Haarmans, M.; Bulst, M.; Lee, K.; Wegner, S.; Hankemeier, T.; Joore, J. High throughput transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements on perfused membrane-free epithelia. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 1676–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, D.M.; Gosav, E.M.; Radu, S.; Costea, C.F.; Ciocoiu, M.; Carauleanu, A.; Lacatusu, C.M.; Maranduca, M.A.; Floria, M.; Rezus, C. The predictive role of the biomarker kidney molecule-1 (KIM-1) in acute kidney injury (AKI) cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechtenberg, M. Towards a Microphysiological iPSC-Derived Proximal Tubule Model. 2025. Available online: https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/items/50a3478e-7753-4e48-89d3-2c368b96982a (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Lechtenberg, M.; Chéneau, C.; Riquin, K.; Koenig, L.; Mota, C.; Halary, F.; Dehne, E.-M. A perfused iPSC-derived proximal tubule model for predicting drug-induced kidney injury. Toxicol. Vitr. 2025, 105, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Zhou, X.; Geng, X.; Drewell, C.; Hübner, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, M.; Marx, U.; Li, B. Repeated dose multi-drug testing using a microfluidic chip-based coculture of human liver and kidney proximal tubules equivalents. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, W.T.; Odenwald, M.A.; Turner, J.R.; Zuo, L. Tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 as regulators of epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1514, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.T.T. Scalable Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells into in Two and Three-Dimensional Proximal Tubule Cells. 2023. Available online: https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/handle/fub188/39301 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Karpman, D.; Ståhl, A.-L.; Arvidsson, I. Extracellular vesicles in renal disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergunay, T.; Collino, F.; Bianchi, G.; Sedrakyan, S.; Perin, L.; Bussolati, B. Extracellular vesicles in kidney development and pediatric kidney diseases. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. Innovative In Vitro Platforms for Investigating Therapeutic Effects and Bio-Distribution of Extracellular Vesicles: Towards Animal-Free Kidney Disease Modelling. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eirin, A.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Jonnada, S.; Lerman, A.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Lerman, L.O. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles improve the renal microvasculature in metabolic renovascular disease in swine. Cell Transplant. 2018, 27, 1080–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Zhang, J.; Shi, L.; Shi, H.; Xu, W.; Jin, J.; Qian, H. Engineered extracellular vesicle-encapsulated CHIP as novel nanotherapeutics for treatment of renal fibrosis. NPJ Regen. Med. 2024, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiro, K.; Lay, A.C.; Leparc, G.; Tran, V.D.T.; Rosler, M.; Dayalan, L.; Burdet, F.; Ibberson, M.; Coward, R.J.; Huber, T.B. An in vitro approach to understand contribution of kidney cells to human urinary extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2023, 12, 12304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Chen, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, L. Embryonic stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote the recovery of kidney injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, J.H.; Liu, Y.; Gao, H.; Dominguez, J.M.; Xie, D.; Kelly, K.J. Renal tubular cell-derived extracellular vesicles accelerate the recovery of established renal ischemia reperfusion injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 3533–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Q.; Liu, J.-F.; Liu, H.; Meng, Y. Extracellular vesicles for ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of data from animal models. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, L.; Nishiga, M.; Cong, L.; Wu, J.C. Deciphering pathogenicity of variants of uncertain significance with CRISPR-edited iPSCs. Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preval, K. Transcriptomic and Therapeutic Insights in ADPKD Identify Tumor-Associated Calcium Signal Transducer 2 (TACSTD2) as a Cyst-Specific Target. 2025. Available online: https://repository.escholarship.umassmed.edu/entities/publication/40ff6e37-cb62-4d34-9d62-3559c283c08c (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Zelikovic, I.; Szargel, R.; Hawash, A.; Labay, V.; Hatib, I.; Cohen, N.; Nakhoul, F. A novel mutation in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, as a cause of Gitelman and Bartter syndromes. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Lee, J.; Heo, N.J.; Cheong, H.I.; Han, J.S. Mutations in SLC12A3 and CLCNKB and their correlation with clinical phenotype in patients with Gitelman and Gitelman-like syndrome. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, D.M.; Rehm, H.L. Will variants of uncertain significance still exist in 2030? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzhagen, J.T.; Noel, S.; Lee, K.; Sadasivam, M.; Gharaie, S.; Ankireddy, A.; Lee, S.A.; Newman-Rivera, A.; Gong, J.; Arend, L.J. T cell Nrf2/Keap1 gene editing using CRISPR/Cas9 and experimental kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 38, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellas, C.P.; Jansen, K.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Clevers, H.; Verhaar, M.C.; Masereeuw, R. Regulation of solute carriers oct2 and OAT1/3 in the kidney: A phylogenetic, ontogenetic, and cell dynamic perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 993–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomini, K.M.; Yee, S.W.; Koleske, M.L.; Zou, L.; Matsson, P.; Chen, E.C.; Kroetz, D.L.; Miller, M.A.; Gozalpour, E.; Chu, X. New and emerging research on solute carrier and ATP binding cassette transporters in drug discovery and development: Outlook from the international transporter consortium. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 112, 540–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-h.; Kim, N.; Okafor, I.; Choi, S.; Min, S.; Lee, J.; Bae, S.-M.; Choi, K.; Choi, J.; Harihar, V. Sniper2L is a high-fidelity Cas9 variant with high activity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Jiao, Y.; An, J.; Tian, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhuo, L. Integrated multi-omics with machine learning to uncover the intricacies of kidney disease. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Nescolarde, A.B.; Piran, M.; Perlaza-Jiménez, L.; Barlow, C.K.; Steele, J.R.; Deveson, D.; Lee, H.-C.; Moreau, J.L.; Schittenhelm, R.B.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J. Hypoxic injury triggers maladaptive repair in human kidney organoids. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakwaa, F.; Das, V.; Majumdar, A.; Nair, V.; Fermin, D.; Dey, A.B.; Slidel, T.; Reilly, D.F.; Myshkin, E.; Duffin, K.L. Leveraging complementary multi-omics data integration methods for mechanistic insights in kidney diseases. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e186070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surian, N.U.; Batagov, A.; Wu, A.; Lai, W.B.; Sun, Y.; Bee, Y.M.; Dalan, R. A digital twin model incorporating generalized metabolic fluxes to identify and predict chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görtz, M.; Brandl, C.; Nitschke, A.; Riediger, A.; Stromer, D.; Byczkowski, M.; Heuveline, V.; Weidemüller, M. Digital twins for personalized treatment in uro-oncology in the era of artificial intelligence. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2026, 23, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amparore, D.; Piana, A.; Piramide, F.; De Cillis, S.; Checcucci, E.; Fiori, C.; Porpiglia, F. 3D anatomical digital twins: New generation virtual models to navigate robotic partial nephrectomy. BJUI Compass 2025, 6, e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Uchimura, K.; Donnelly, E.L.; Kirita, Y.; Morris, S.A.; Humphreys, B.D. Comparative analysis and refinement of human PSC-derived kidney organoid differentiation with single-cell transcriptomics. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 869–881.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Ziyadeh, E.; Sharma, Y.; Dumoulin, B.; Levinsohn, J.; Ha, E.; Pan, S.; Rao, V.; Subramaniyam, M.; Szegedy, M. Nephrobase Cell+: Multimodal Single-Cell Foundation Model for Decoding Kidney Biology. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.26223. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Kuppe, C.; Perales-Patón, J.; Hayat, S.; Kranz, J.; Abdallah, A.T.; Nagai, J.; Li, Z.; Peisker, F.; Saritas, T. Adult human kidney organoids originate from CD24+ cells and represent an advanced model for adult polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 1690–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Hwang, J.S.; Zhai, Z.; Park, K.; Son, Y.S.; Kim, D.S.; Chung, S.; Kim, S.; Son, M.Y.; Lee, G. Apical-out Tubuloids for Accurate Kidney Toxicity Studies. Aggregate 2025, 6, e697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, Y.; Mori, M.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Morita, I.; Shindoh, R.; Mandai, S.; Fujiki, T.; Kikuchi, H.; Ando, F.; Susa, K. Recapitulation of Cellular Senescence, Inflammation, and Fibrosis in Human Kidney-Derived Tubuloids by Repeated Cisplatin Treatment: A Novel Pathophysiological Model for Sensing Nephrotoxicity and Drug Screening. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, Y.; Mori, M.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Morita, I.; Shindoh, R.; Mandai, S.; Fujiki, T.; Kikuchi, H.; Ando, F.; Susa, K. A Human Kidney Tubuloid Model of Repeated Cisplatin-Induced Cellular Senescence and Fibrosis for Drug Screening. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, e01795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedecostante, M.; Westphal, K.G.; Buono, M.F.; Romero, N.S.; Wilmer, M.J.; Kerkering, J.; Baptista, P.M.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Masereeuw, R. Recellularized native kidney scaffolds as a novel tool in nephrotoxicity screening. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, P.; Rodrigues, A.D.; Steppan, C.M.; Engle, S.J.; Mathialagan, S.; Schroeter, T. Human pluripotent stem cell–derived kidney model for nephrotoxicity studies. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmen, E.; Hanhof, C.O.; Yengej, F.Y.; Ammerlaan, C.; Rookmaaker, M.; Orhon, I.; Jansen, J.; Verhaar, M.; Hoenderop, J. A semi-permeable insert culture model for the distal part of the nephron with human and mouse tubuloid epithelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2025, 444, 114342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olde Hanhof, C.; Dilmen, E.; Yousef Yengej, F.; Latta, F.; Ammerlaan, C.; Schreurs, J.; Hooijmaijers, L.; Jansen, J.; Rookmaaker, M.; Orhon, I.; et al. Differentiated mouse kidney tubuloids as a novel in vitro model to study collecting duct physiology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1086823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumilas, D.; Owczarek, A.J.; Brzozowska, A.; Niemir, Z.I.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M.; Chudek, J. The value of urinary NGAL, KIM-1, and IL-18 measurements in the early detection of kidney injury in oncologic patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekjürgen, D.; Grainger, D.W. Drug transporter expression profiling in a three-dimensional kidney proximal tubule in vitro nephrotoxicity model. Pflügers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol. 2018, 470, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

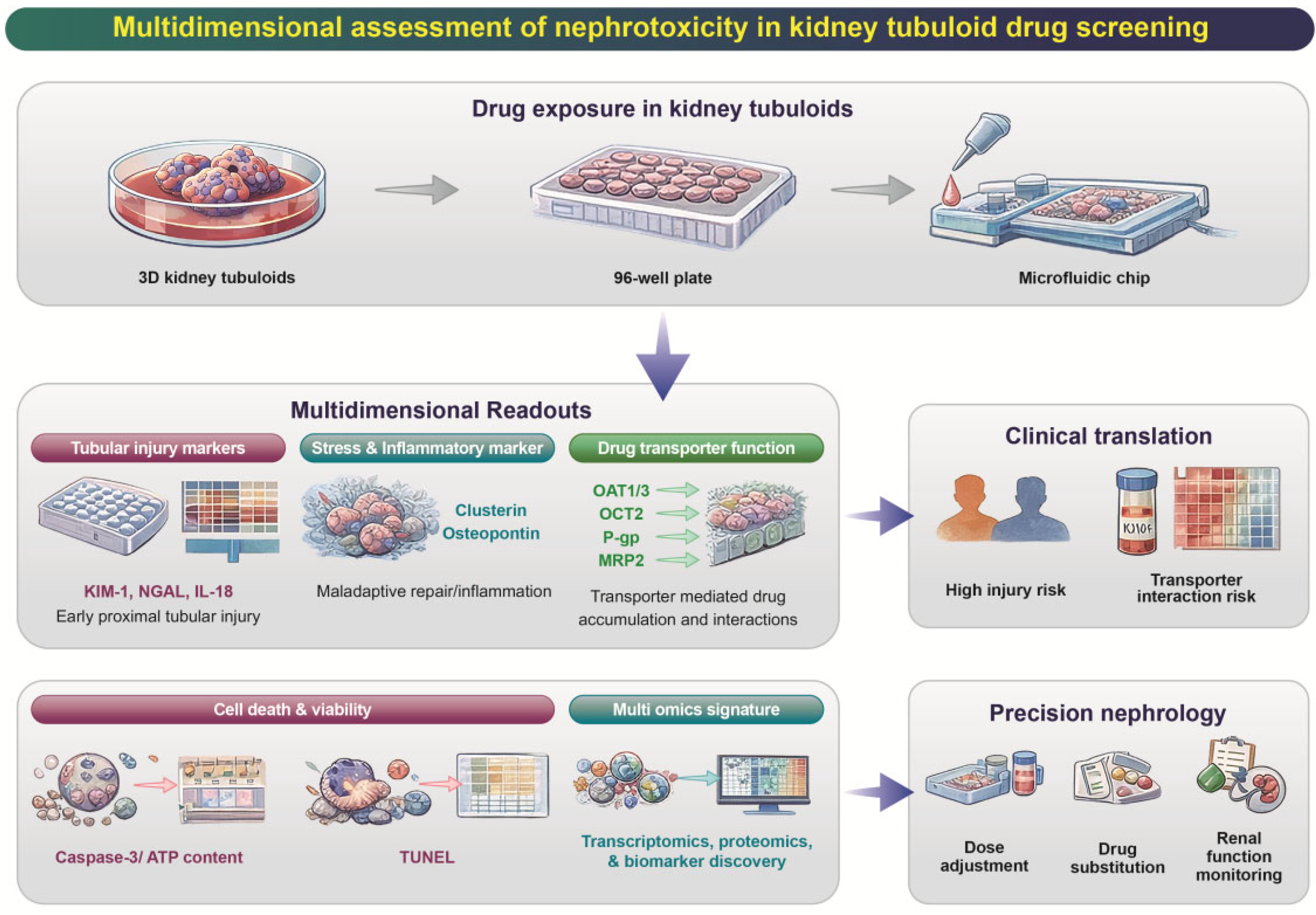

- Yu, P.; Duan, Z.; Liu, S.; Pachon, I.; Ma, J.; Hemstreet, G.P.; Zhang, Y. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity assessment in 3D cellular models. Micromachines 2021, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.P.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, A.W.H.; Teo, J.C.M. A Fibrin-Based Tissue-Engineered Renal Proximal Tubule for Bioartificial Kidney Devices: Development, Characterization and In Vitro Transport Study. Int. J. Tissue Eng. 2013, 2013, 319476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model System | Primary Source | Transporter Expression * | Barrier Function (TEER) * | Injury/Stress Marker Response | Maturation Level | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native human kidney | Adult renal tissue | Reference standard (100%) for OCT2, OAT1/3, MATE1/2-K, P-gp | High, physiological (>1000 Ω·cm2, segment-dependent) | Robust, clinically validated (KIM-1, NGAL) | Fully mature | Standard physiology | Limited availability; non-scalable |

| Tissue-derived kidney tubuloids | Adult kidney biopsy | High and stable; ~50–90% of adult levels for key transporters | Moderate–high (≈200–800 Ω·cm2) | Strong KIM-1, NGAL induction after toxic/ischemic stress | High | Closest in vitro adult tubular phenotype | Donor variability; no vasculature/immune cells |

| Urine-derived kidney tubuloids | Exfoliated renal epithelial cells | Moderate–high; comparable to tissue-derived tubuloids for proximal markers | Moderate (≈150–600 Ω·cm2) | Reproducible KIM-1, NGAL responses | Intermediate–high | Non-invasive, repeat sampling | Heterogeneous starting material |

| iPSC-derived kidney tubuloids | Differentiated hiPSCs | Moderate; higher than PSC organoids but below adult tissue | Low–moderate (≈50–300 Ω·cm2) | Detectable injury responses; lower dynamic range | Intermediate | Scalable; genetically editable | Incomplete maturation |

| PSC-derived kidney organoids | hESCs/hiPSCs | Low–moderate; fetal-like transporter profiles | Low (<100 Ω·cm2) | Injury marker induction inconsistent | Low–intermediate | Developmental modeling | Immaturity; batch variability |

| Category | Markers/Readouts | Indication | Relevance for Precision Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tubular injury markers | KIM-1, NGAL, IL-18 | Proximal tubule injury and stress response | Early and sensitive detection of drug-induced kidney injury |

| Stress and inflammation markers | CLU, SPP1, cytokine release | Cellular stress, inflammation, maladaptive repair | Mechanistic stratification of nephrotoxic responses |

| Transporter expression & function | OAT1, OAT3, OCT2, P-gp, MRP2 | Drug uptake/efflux and accumulation | Prediction of transporter-mediated nephrotoxicity and drug–drug interactions |

| Barrier and epithelial integrity | ZO-1, occludin, epithelial polarity | Tubular barrier disruption and loss of differentiation | Assessment of functional epithelial damage |

| Cell death and viability | Caspase-3 activation, TUNEL, ATP content | Apoptosis and cytotoxicity | Quantification of dose-dependent toxicity |

| Multi-omics injury signatures | Transcriptomics, proteomics, secretome profiling | Pathway-level toxicity mechanisms | Personalized toxicity profiling and biomarker discovery |

| Functional physiology | Transport assays, metabolic activity | Tubular functional competence | Improved translational relevance compared to 2D cultures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hossain, M.K.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, H.-R. Translational Potential: Kidney Tubuloids in Precision Medicine and Regenerative Nephrology. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020147

Hossain MK, Lee H-Y, Kim H-R. Translational Potential: Kidney Tubuloids in Precision Medicine and Regenerative Nephrology. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(2):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020147

Chicago/Turabian StyleHossain, Muhammad Kamal, Hwa-Young Lee, and Hyung-Ryong Kim. 2026. "Translational Potential: Kidney Tubuloids in Precision Medicine and Regenerative Nephrology" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 2: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020147

APA StyleHossain, M. K., Lee, H.-Y., & Kim, H.-R. (2026). Translational Potential: Kidney Tubuloids in Precision Medicine and Regenerative Nephrology. Pharmaceutics, 18(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18020147