1. Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory disease that affects approximately 2–3% of the world’s population. It is a relapsing skin disorder that has a significant impact on the patients’ quality of life due to its visible, persistent, and clinically difficult-to-control nature. The pathophysiology of psoriasis is characterized by hyperproliferation of keratinocytes, infiltration of T lymphocytes and other immune cells, as well as the overexpression of proinflammatory mediators, resulting in thickened, scaly, erythematous plaques [

1,

2]. Psoriasis is also a risk factor for multiple comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome [

3], cardiovascular disease [

4], depression, and anxiety [

5], accentuating its clinical and social relevance. In addition to immune dysregulation, psoriasis is characterized by a marked impairment of the epidermal barrier, resulting in increased transepidermal water loss and altered stratum corneum hydration.

Available therapeutic options include topical, systemic, and biological treatments. Topical agents, such as corticosteroids, retinoids, and vitamin D analogs, constitute the first-line treatment for mild-to-moderate forms [

6]. However, their effectiveness may be limited, and long-term use is associated with adverse local effects on the skin, such as irritation or skin atrophy [

7]. On the other hand, conventional systemic treatments (such as acitretin, methotrexate, and cyclosporine) and the most recent biological treatments have shown high clinical efficacy. However, they carry risks of liver toxicity, nephrotoxicity, immunosuppression, or serious infections, which restrict their prolonged use [

8].

In recent years, Janus kinase (JAK) pathway inhibitors have been considered as a therapeutic alternative for various inflammatory diseases [

9,

10]. Baricitinib (BCT) is a selective inhibitor of Janus kinases JAK1 and JAK2, whose action blocks the signaling of various cytokines involved in the inflammatory response, such as interleukins (IL-6, IL-12, IL-23) and type I and II interferons. In this way, it prevents the phosphorylation and activation of STATs (Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription); therefore, BCT interrupts the JAK-STAT cascade responsible for keratinocyte proliferation and immune cell activation [

11]. Baricitinib has demonstrated its clinical efficacy in moderate-to-severe psoriasis in a randomized phase 2b trial: patients receiving 8 mg or 10 mg once daily for 12 weeks achieved significantly higher PASI-75 responses compared with placebo (43% and 54% vs. 17%) [

12]. However, oral administration of BCT has been associated with significant systemic adverse effects, including an increased risk of opportunistic infections, deep vein thrombosis, and cardiovascular events [

13,

14]. These limitations have prompted the search for topical formulations of baricitinib that can target the drug at the site of application, reducing systemic exposure and improving the safety profile [

12,

15,

16]. For instance, a topical JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor cream (ruxolitinib phosphate, INCB018424) showed proof-of-concept efficacy in a vehicle-controlled clinical trial for plaque psoriasis, significantly improving lesion thickness, erythema, and scaling compared with a placebo [

17]. Although there are very few studies on the topical use of BCT in psoriasis, Bhaskarmurthy DH et al. demonstrated its in vivo efficacy in a psoriasis-like skin inflammation model, as evidenced by the reduction in inflammatory markers [

18]. Furthermore, in previous work by our research group, topical BCT formulations using lipid systems were developed. These oily solutions improved drug solubility, promoted cutaneous retention, and demonstrated efficacy in mouse models of psoriasis [

19].

The therapeutic efficacy of topical treatments in psoriasis is influenced not only by the active ingredient, but also by the physicochemical properties of the vehicle, which determine skin hydration, barrier modulation and drug penetration [

20,

21]. Sustained stratum corneum hydration is primarily driven by the reduction in transepidermal water loss through occlusive mechanisms rather than by humectation alone. Thus, stratum corneum hydration (SCH) and transepidermal water loss (TEWL) are complementary biophysical parameters widely used to assess the impact of topical formulations on skin hydration dynamics and epidermal barrier function.

Petrolatum is a classic and widely used excipient in dermatological formulations, thanks to its emollient, occlusive, and moisturizing properties [

22]. Liquid petrolatum (LLV) is characterized by its ease of application and good spreadability, while solid petrolatum (LSV) offers greater occlusivity and persistence on the skin [

23]. These differences in physical behavior can significantly impact the biopharmaceutical performance of an incorporated drug, particularly in terms of local release and retention. However, to date, no studies have systematically compared the effects of liquid and solid petrolatum in lipid-based BCT formulations.

In this context, this study aims at evaluating the impact of petrolatum type (liquid vs. solid) and its concentration on lipid formulations of BCT solubilized in MCT (Labrafac® Lipophile WL 1349 (L) on skin hydration, epidermal barrier function and the topical delivery and antipsoriatic activity of baricitinib. The incorporation of different petrolatum, such as liquid and semi-solid petrolatum, is expected to generate formulations with graded occlusive properties, enabling a systematic evaluation of their impact on TEWL reduction and stratum corneum hydration.

4. Discussion

In this work, we developed lipid-based topical formulations containing baricitinib at a concentration of 0.04% for the treatment of psoriasis. Baricitinib, a selective JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, has demonstrated clinical efficacy in systemic administration for inflammatory skin diseases; however, topical delivery may represent a safer and more targeted therapeutic approach by minimizing systemic exposure. The rationale for exploring the topical route is supported by prior success with other JAK inhibitors used dermally. For instance, ruxolitinib cream, used to treat atopic dermatitis and vitiligo [

16,

35], is one example. Studies by Naeimifar A. et al. developed a topical nanoliposomal formulation of this same active ingredient, demonstrating optimal physicochemical properties; however, the study did not demonstrate in vivo efficacy [

38]. Nevertheless, clinical trials have been conducted with ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of psoriasis. In this study, patients received a vehicle without an active ingredient and a vehicle with ruxolitinib phosphate at 0.5% and 1.0% once daily, or at 1.5% twice daily, for 28 days. Additional groups included two active comparators: calcipotriol cream 0.005% or betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. The results showed that both the 1% and 1.5% creams improved lesion thickness, erythema, and scaling and reduced their area compared to placebo [

17].

Other JAK1 inhibitors have also been used to be delivered in cream form for the treatment of psoriasis, such as Brepocitinib which was used to test its efficacy in cases of mild or moderate plaque psoriasis in a randomized phase IIb clinical study, however, the results were not very encouraging since although the cream was well tolerated, it did not produce statistically significant changes compared to the vehicle without the drug [

39].

Finally, a randomized, phase IIb clinical trial of tofacitinib ointment (a JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor and some JAK2 inhibitors) was conducted in patients with plaque psoriasis for 12 weeks. The study demonstrated that the 2% ointment, applied once or twice daily, showed greater efficacy than the vehicle-free ointment at week 8, suggesting that the topical route of a JAK inhibitor may offer a promising alternative for the treatment of psoriasis. However, the lack of statistically significant differences among many regimens at week 12 raised concerns about the magnitude and duration of the clinical effect under the conditions of this study [

40]. Nevertheless, the very low systemic exposure and acceptable tolerability profile with the vehicle used support the safety of short-term topical application as shown in this study.

The results obtained demonstrate that the type of petrolatum, whether solid (LSV) or liquid (LLV), exerts a decisive effect on the release, permeation, cutaneous retention, and biological activity of BCT. Following the experimental design, it was indicated that only formulations with 30% petrolatum (LSV2 and LLV2) showed adequate physicochemical profiles over 60 days (

Table 4;

Table 5), confirming that the selection of the vehicle not only determines the release properties but also the medium-term stability, a critical aspect in lipid formulations [

41]. On the other hand, the pH values of the formulations were maintained between 5 and 6, which is ideal for skin application. This is important since the skin barrier and microbiota balance must be maintained to prevent skin irritation and sensitivity [

42]. The chemical stability of baricitinib within the topical lipid-based formulations was satisfactory under both intermediate (30 °C/65% RH) and accelerated (40 °C/75% RH) storage conditions. The estimated t

90 values (ranging from approximately 75 to 152 days) indicate that the formulations maintained at least 90% of their initial drug content for periods exceeding two to five months, depending on temperature. The rate constants (k) approximately doubled with each 10 °C increase, in agreement with the Arrhenius equation, suggesting that the degradation process is thermally activated.

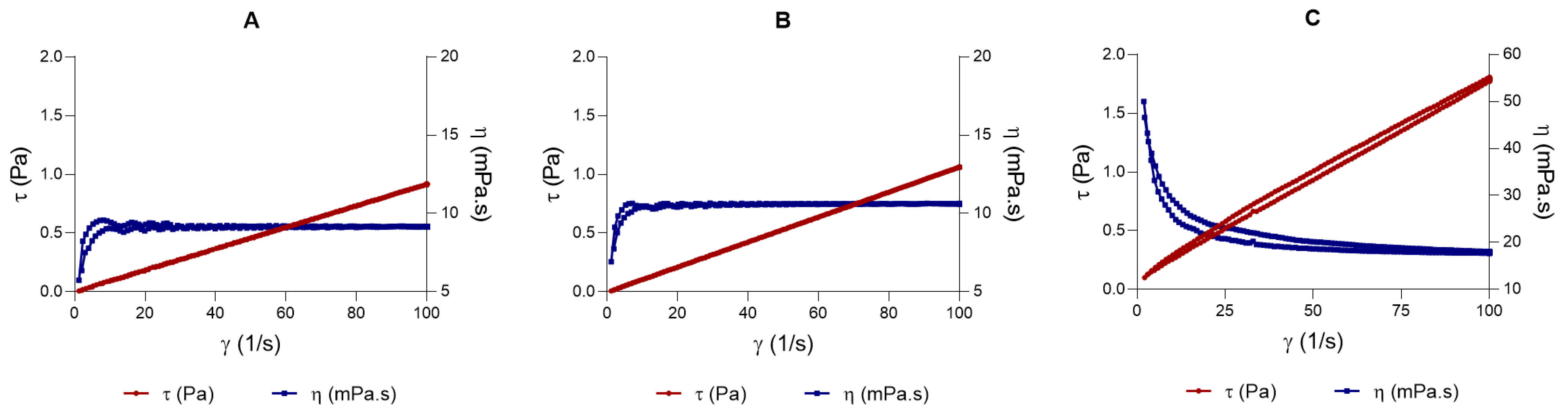

Rheology in topical formulations is not just a physical-chemical parameter; it is crucial for the product’s stability, efficacy, and clinical acceptability [

43]. The LSV exhibited pseudoplastic behavior and higher viscosity, whereas LLV displayed a Newtonian profile with reduced viscosity. These differences directly influence spreadability: the LLV formulation disperses more easily over the surface, which is advantageous for topical application on large or sensitive areas. In contrast, LSV, with greater structural rigidity, exhibited lower spreadability, which may limit application uniformity but enhance occlusivity and, therefore, transdermal penetration [

44,

45].

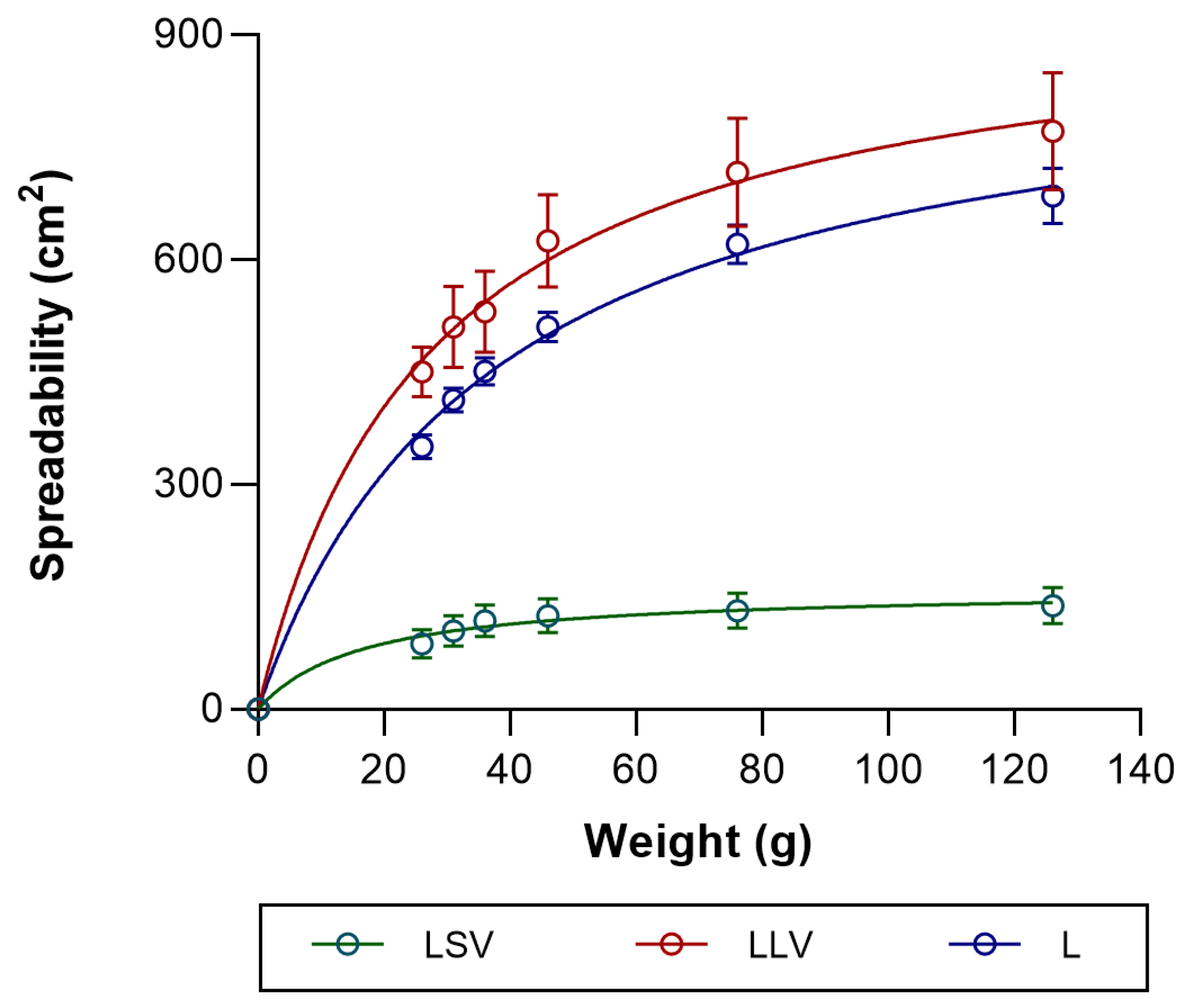

Spreadability is an essential parameter in topical formulations, as it determines their ease of application and skin coverage. In this study, LLV was favored due to its greater spreadability, which is attributed to its low viscosity, thereby optimizing dispersion and clinical acceptability. On the other hand, LSV exhibited lower spreadability, which is associated with its structural rigidity, although it may have a potential occlusive effect that could benefit skin penetration. Thus, the balance between spreadability and occlusivity is decisive for therapeutic efficacy [

46]. A relationship was observed between the rheological and spreadability characteristics of the formulations and the amount of baricitinib released in vitro. The formulation with lower viscosity and greater extensibility (LLV) showed a higher cumulative drug release compared to the more viscous system (LSV), suggesting that softer and more easily spreadable vehicles facilitate drug diffusion through the matrix. This finding is consistent with previous works showing an inverse correlation between viscosity and drug release from semisolid systems [

47,

48]. The rheological behavior determines the internal structure and mobility of the vehicle, which directly influences diffusion and drug availability. Higher viscosity impedes drug diffusion by creating a denser matrix, reducing the mobility of the drug molecule [

49].

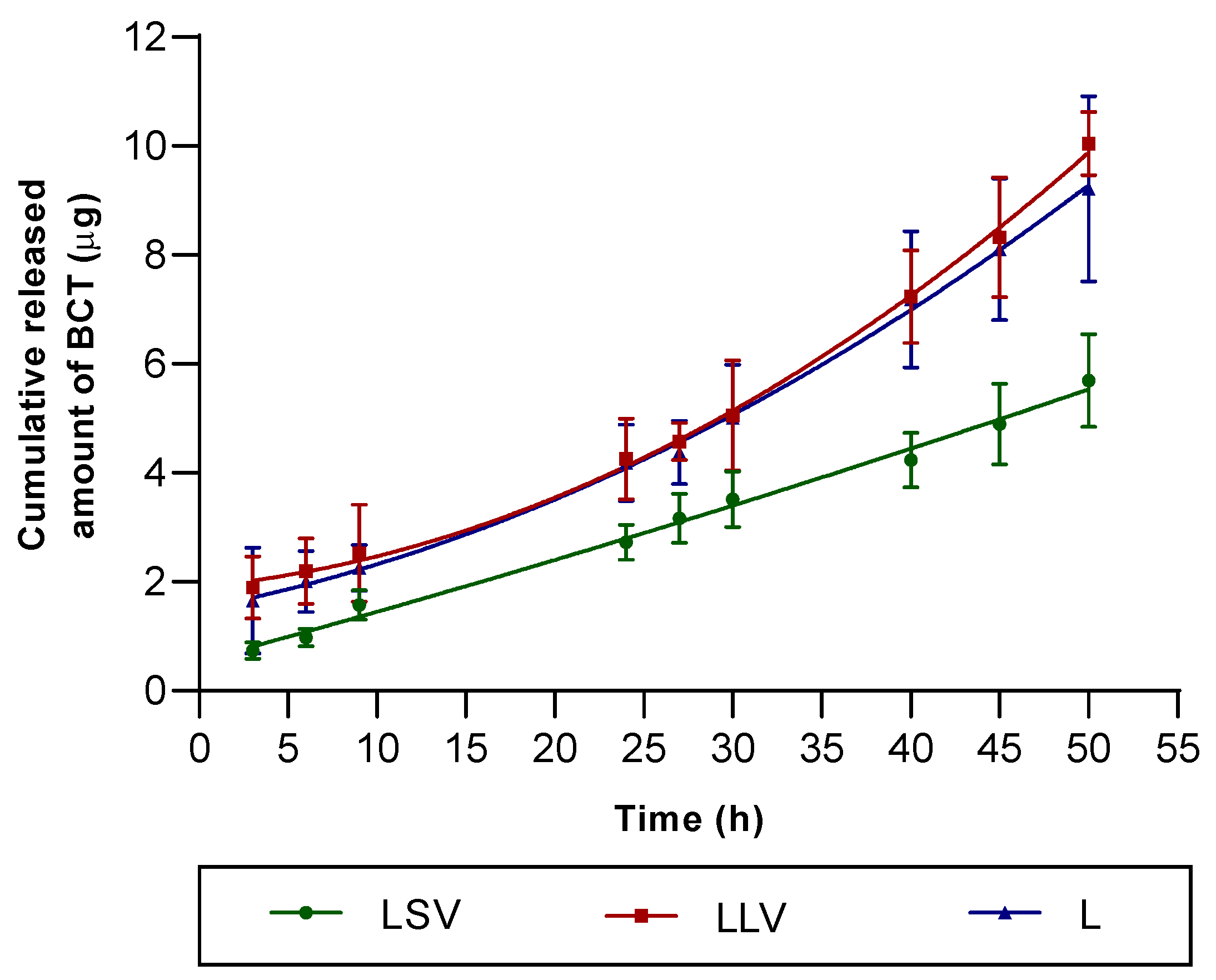

The in vitro release test was conducted to evaluate the release profile of baricitinib from the formulation independently of the skin barrier. Therefore, an inert synthetic membrane (dialysis membrane, MWCO 14 kDa) was selected to act merely as a physical support separating the formulation from the receptor medium, without influencing drug diffusion. This approach complies with the recommendations of the EMA Guideline on quality and equivalence of locally applied and locally acting cutaneous products (EMA/CHMP/QWP/708282/2018) [

49], which distinguish between in vitro release test —where an inert membrane is required—and in vitro permeation studies, where human or animal skin should be employed to evaluate permeation through the stratum corneum. The in vitro release study showed that liquid petrolatum (LLV) favors a higher and sustained release of BCT compared to solid petrolatum, reaching more than 80% of the drug released at 50 h (

Figure 5). This finding is consistent with previous work in which fluid lipid vehicles increase the molecular mobility of the active ingredient and facilitate its diffusion to the skin surface [

19]. According to the Korsmeyer–Peppas model, the diffusion exponent (n) is an empirical parameter that characterizes the mechanism of drug release from a semisolid or polymeric matrix. It reflects the relative contribution of Fickian diffusion and relaxation or erosion processes within the vehicle, thus providing insight into whether the release follows purely diffusional, anomalous (non-Fickian), or zero-order kinetics. The observed Korsmeyer–Peppas exponent values (

n = 0.73–0.78) for our Labrafac- and petrolatum-based ointments are consistent with anomalous (non-Fickian) transport, indicating a combined contribution of diffusion and time-dependent changes at the vehicle interface. This behaviour has been reported specifically for oleaginous ointment bases, where a transient interfacial boundary layer and dynamic microstructural rearrangements govern the release rather than pure Higuchi-type diffusion. Experimental and review studies on ointments and other non-swelling lipidic matrices have emphasised that release kinetics from such bases frequently deviate from simple diffusion models and are better interpreted through models that allow mixed mechanisms (e.g., Korsmeyer–Peppas). These observations support the plausibility and external validity of our findings for Labrafac/petrolatum semisolid systems.

However, the correlation with ex vivo permeation was not linear: LSV, despite releasing less drug, promoted a higher permeation (

Figure 6). The receptor medium composed of PBS–Transcutol (50:50

v/

v) was selected to ensure sink conditions during the ex vivo skin permeation studies, since the aqueous solubility of baricitinib in PBS alone is very low. As previously demonstrated by our group, the inclusion of Transcutol markedly increases baricitinib solubility [

25]. Additionally, the medium showed to be biocompatible with the skin, as confirmed by TEWL measurements at the end of the tests. Regarding the experimental conditions, a stirring speed of 600 rpm was used to minimize the stagnant boundary layer beneath the membrane and to better emulate the in vivo situation, where continuous blood flow removes the permeated drug from the dermal–vascular interface. This stirring rate has been recommended by methodological guidelines [

50] and is frequently applied in Franz diffusion studies to maintain homogeneous receptor conditions and reproducible flux measurements [

51]. This finding shows that occlusivity and the vehicle’s ability to alter the skin barrier are as determining as the release rate in the final absorption profile [

52,

53]. Percutaneous absorption is primarily a passive diffusion process and can be described by Fick’s laws. However, the true driving force for transdermal transport is the thermodynamic activity—that is, the chemical-potential gradient of the drug between the formulation and the skin—rather than the nominal concentration alone. When the drug is near or at saturation in the vehicle, its thermodynamic activity is maximized and the potential for partitioning into the stratum corneum increases. Vehicle occlusivity modulates this process through two principal mechanisms. First, occlusive excipients (e.g., petrolatum, mineral oil, dimethicone) reduce transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and thereby increase stratum corneum hydration, which typically raises the diffusion coefficient within the barrier and can enhance permeation for lipophilic compounds. Second, occlusion and vehicle composition influence solvent evaporation: volatile components will evaporate from non-occlusive vehicles, concentrating the drug and potentially increasing its thermodynamic activity at the skin surface, whereas highly occlusive vehicles maintain solvent and drug in a solubilized state, which can lower thermodynamic activity and the net driving force. Thus, the net effect of occlusivity on permeation depends on the balance between increased skin hydration (which tends to increase permeability) and changes in the drug’s thermodynamic activity (which may increase or decrease the diffusion gradient). In our formulations, the relative proportions of Labrafac and liquid versus solid vaseline modulate occlusivity and co-solvent behavior, providing a mechanistic explanation for the differences in release and permeation observed in the permeation test [

54].

A relevant aspect was differential cutaneous retention: LLV presented the highest amount of BCT accumulated in the skin, followed by lipid control (L) and finally LSV. These results suggest that the lower viscosity of LLV favors intracutaneous deposition and accumulation of the drug in the epidermal matrix, which is desirable for topical therapies targeting psoriasis lesions, where a sustained local action rather than systemic penetration is sought [

55]. This balance between retention and permeation is crucial for optimizing the safety of topical BCT formulations, given the cardiovascular and thrombotic risks associated with their oral use [

13,

14].

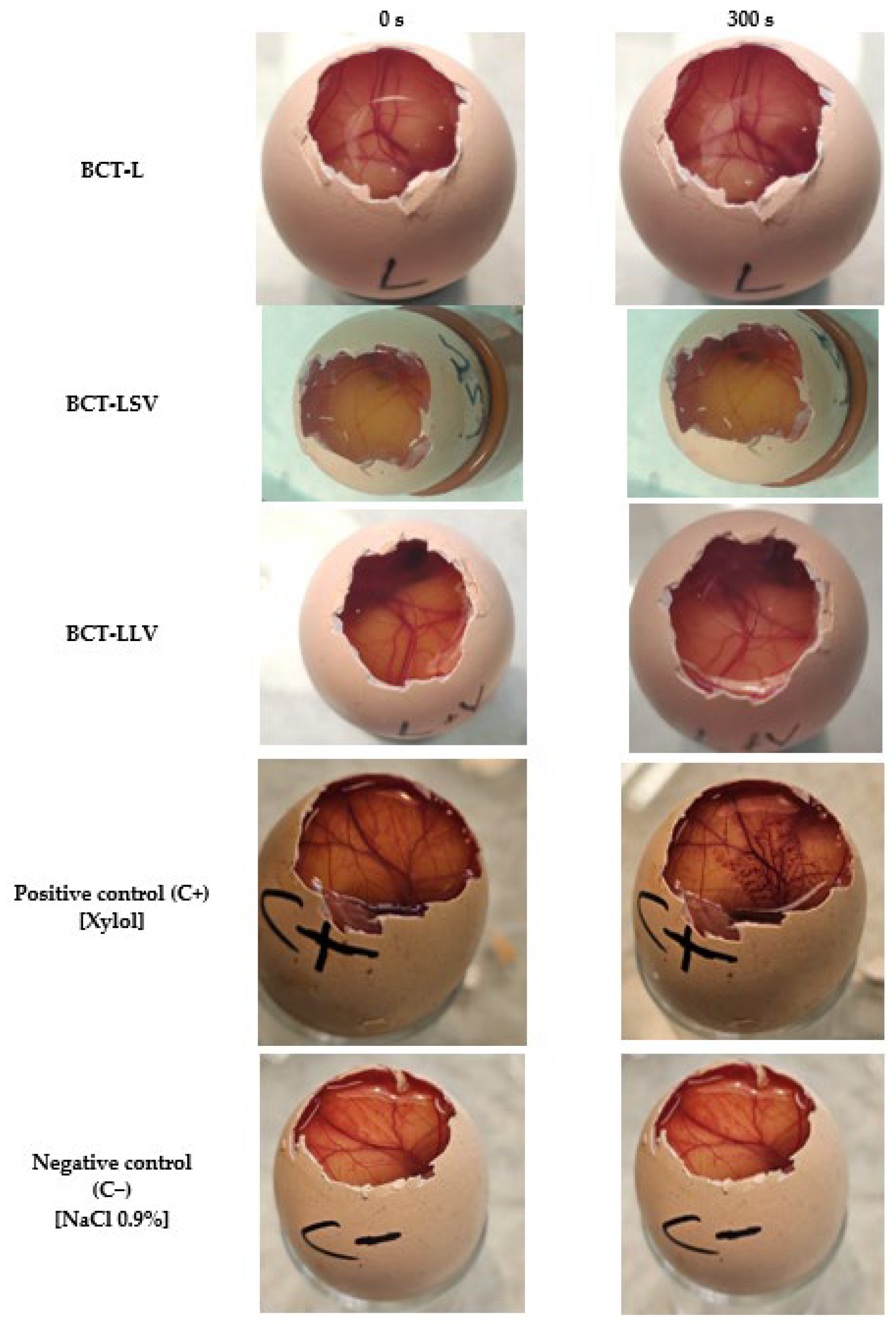

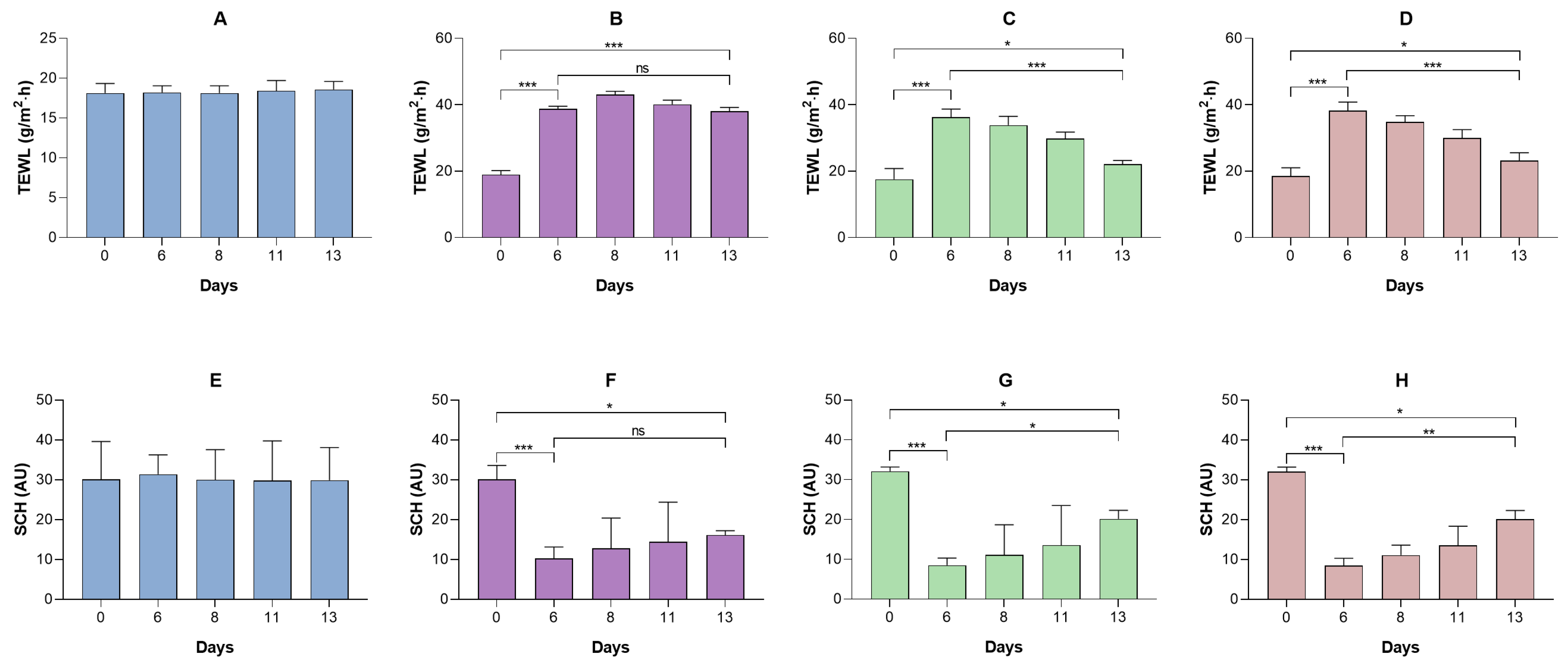

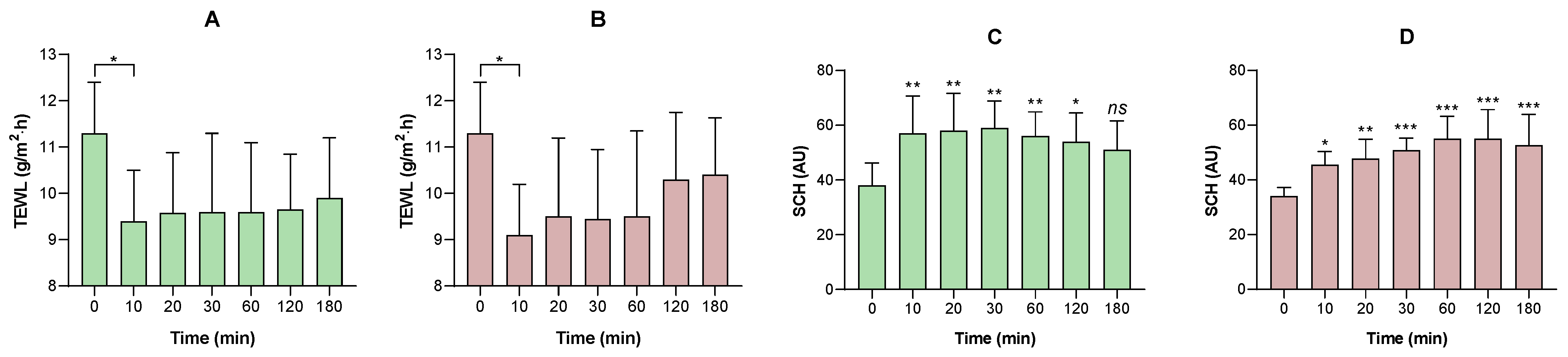

No formulation induced irritation in the HET-CAM assay or in vivo models, consistent with the non-irritating profile of excipients such as MCT and petrolatum. Furthermore, in humans, excipients (placebo formulations) have been shown to transiently improve stratum corneum hydration and reduce transepidermal water loss, confirming an emollient-occlusive effect. The observed changes in SCH and TEWL may be related to the occlusive capacity of the formulations and their ability to reinforce the epidermal barrier. The water–Transcutol solution, used as a non-occlusive control (

Supplementary Material), induced only an initial increase in the TEWL values. This behavior is consistent with the volatility of the vehicle and the penetration-enhancing properties of Transcutol, which may even transiently disrupt stratum corneum lipid organization, thereby preventing sustained hydration. Labrafac (L), composed of medium-chain triglycerides, exhibited an increase in SCH accompanied by a slight reduction in TEWL, indicating a weak semi-occlusive effect. Medium-chain triglycerides act primarily as emollients, improving skin softness and flexibility, but they do not form a continuous film capable of effectively limiting transepidermal water evaporation. The incorporation of liquid petrolatum into Labrafac (LLV) resulted in a more pronounced reduction in TEWL and a concomitant increase in SCH. Liquid petrolatum enhances film continuity and viscosity at the skin surface, leading to a moderate occlusive effect and improved water retention within the stratum corneum. Similar effects were observed for the formulation containing petrolatum in its semi-solid form (LSV). Petrolatum is known to form a continuous, semi-solid lipid film that markedly limits water evaporation. Accordingly, LSV exhibited TEWL reduction and the progressive SCH increase. Therefore, these findings are consistent with the literature, which attributes a dual function to lipid formulations: serving as both a drug vehicle and a skin barrier restorer [

56]. Furthermore, the use of oily substances could make the skin softer by filling in the gaps between the partially loose skin scales (as occurs in psoriasis). This can restore the ability of the intercellular lipid bilayers to absorb, retain, and distribute water [

57]. Although excipients such as Vaseline and MCT have a well-documented history of safe cosmetic use, the overall formulation and vehicle composition can significantly influence cutaneous responses. The combination of ingredients may modify key parameters such as skin penetration, occlusion, and the release kinetics of other actives. Therefore, even established excipients may behave differently when incorporated into a new formulation matrix [

58,

59]. We are fully aware that the use of healthy volunteers represents a limitation of the study, as psoriasis is characterized by an impaired skin barrier, chronic inflammation, and increased sensitivity. Therefore, results obtained on healthy skin cannot fully predict tolerance in psoriatic skin. Nevertheless, as a preliminary step, it is ethically and scientifically sound to first assess the irritant potential of a novel formulation in healthy individuals. This approach minimizes the risk of exposing patients with compromised skin to potentially irritating formulations, allows early detection of significant irritant reactions, and facilitates optimization of the formulation before conducting studies in more vulnerable populations.

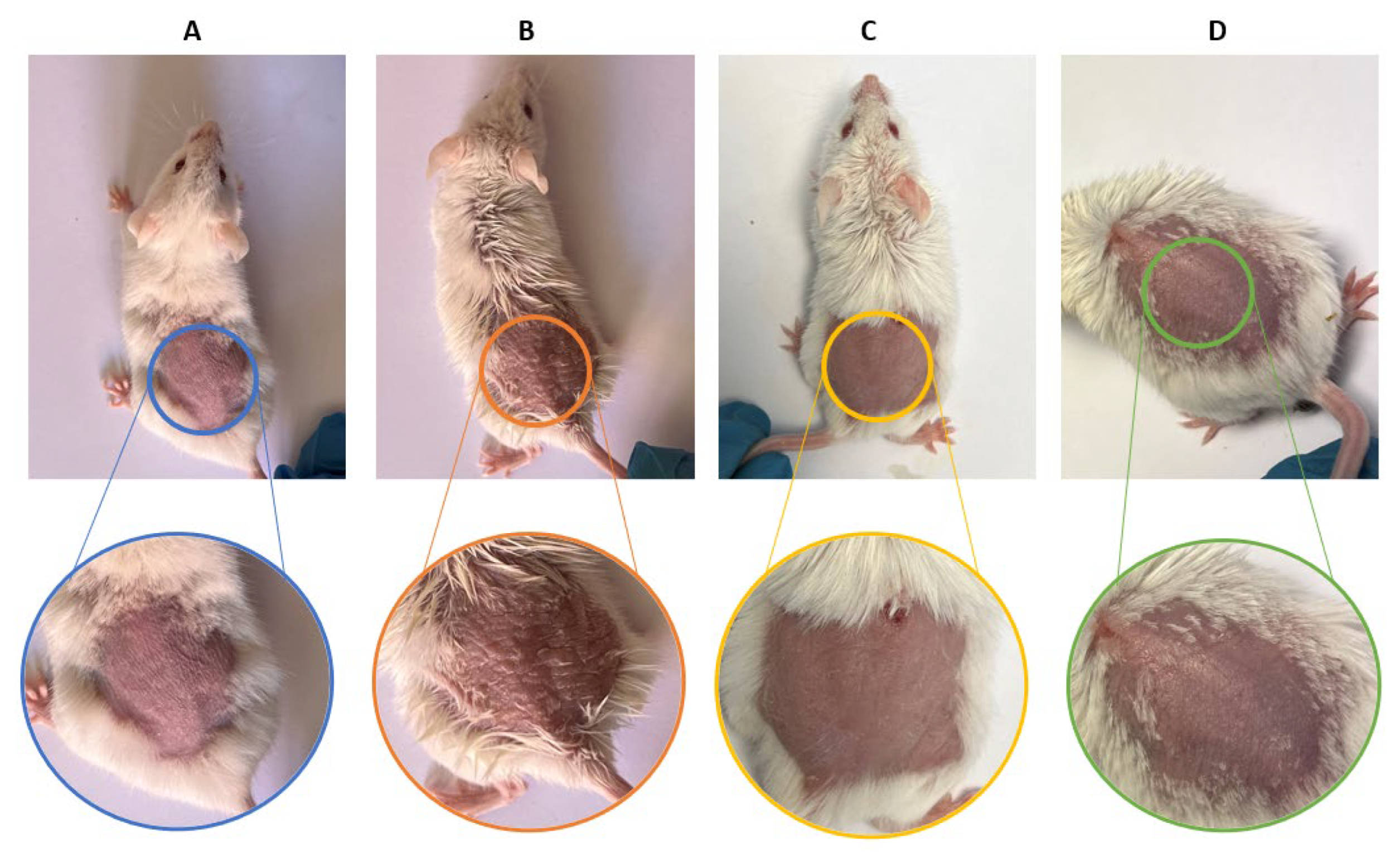

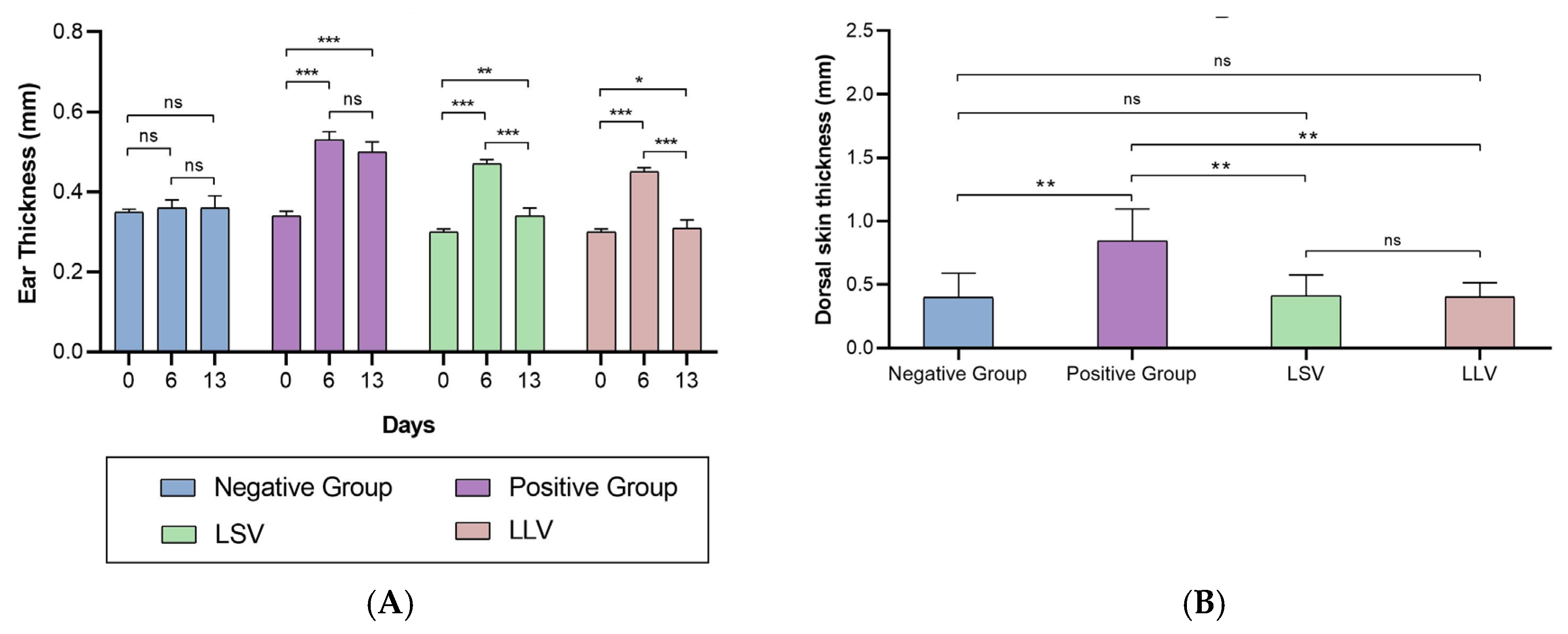

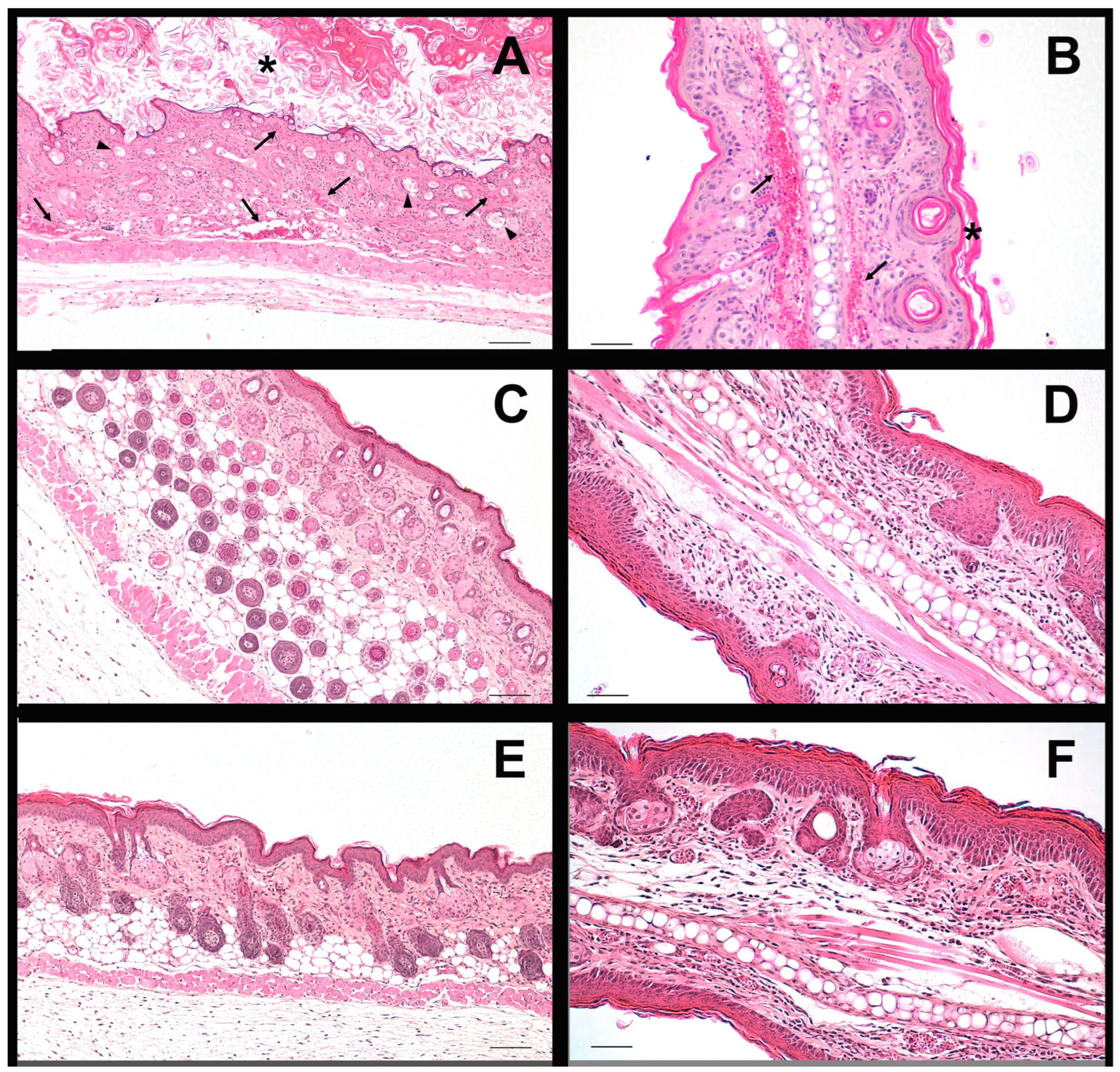

Both formulations showed anti-inflammatory efficacy in the murine model of imiquimod-induced psoriasis, reducing erythema, epidermal thickening and loss of barrier function. Histology confirmed the attenuation of hyperplasia and vascular dilation, effects that reflect the inhibition of the JAK-STAT cascade and possibly the decrease of cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-23, mechanisms previously described for BCT [

9], which is why this result validates that, even with different release and retention profiles, both formulations allow reaching sufficient tissue concentrations to modulate the local inflammatory response. The histological findings confirm that imiquimod induced epidermal hyperplasia and structural disorganization in dorsal skin, while both formulations (LSV and LLV) effectively maintained normal epidermal architecture. In ear skin, however, the inflammatory response appeared to be primarily localized within the dermis, as indicated by the presence of dilated and blood-filled vessels, rather than affecting the epidermal compartment. This explains why no significant differences in epidermal thickness were detected among ear samples, despite clear dermal inflammation in the positive control group. Similar dermis-restricted inflammatory patterns have been described in murine models of topical imiquimod-induced irritation [

60].

An important point of discussion is the inverse relationship between permeation and retention observed between LSV and LLV; while LSV maximized transcutaneous permeation, LLV optimized cutaneous retention. This phenomenon can be interpreted within the framework of the vehicle-stratum corneum partition coefficient and the microstructure of the excipients. Solid petrolatum, being more occlusive, probably favored hydration of the stratum corneum and the opening of transient diffusive channels, facilitating passage into the dermis and circulation, while liquid petrolatum, less occlusive, retained the drug in the epidermis, acting as a reservoir [

46]. Therefore, this duality can be exploited in therapeutic customization: an LLV-type formulation would be ideal for localized lesions that require prolonged action on site.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The sample size in both animal and human studies was relatively small, which may limit the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. In addition, the relatively high standard deviation observed in some in vitro release and ex vivo permeation data can be partly attributed to the limited number of replicates (n = 6), which increases the influence of inter-sample variability. The ex vivo human skin experiments were intended to provide preliminary insight into the ability of the formulations to deliver baricitinib (BCT) into the skin. Although direct comparison with previously published data is limited due to the novelty of topical BCT application, the drug levels retained in the skin were considered potentially effective based on the positive in vivo outcomes in mice. However, given that murine skin is more permeable than human skin, extrapolation between models should be interpreted with caution.

Moreover, although the imiquimod-induced psoriasis model is widely accepted for evaluating psoriatic inflammation, the number of animals per group (n = 5) was determined according to ethical principles of reduction and institutional guidelines, aiming to minimize animal use in exploratory efficacy and tolerability studies. This sample size allows the detection of relatively large treatment effects but provides limited power to identify smaller differences; therefore, confirmatory studies with larger group sizes are warranted to strengthen the robustness and reproducibility of the findings. Additionally, a limitation of the exploratory in vivo efficacy study is the absence of a placebo control group, this decision was aligned with the go/no-go nature of the study, whose primary objective was to determine whether the formulations exhibited sufficient biological activity to warrant further development. The IMQ group provided a robust and reproducible negative control, allowing sensitive detection of therapeutic effects while keeping the design efficient at this early stage. Both formulations reduced erythema, scaling, and skin thickening compared with IMQ controls, meeting the predefined “go” criteria. These results support progression to a pivotal preclinical efficacy study, in which a full placebo arm will be included to provide rigorous and confirmatory comparative data.

Finally, long-term stability testing and sensory or user acceptability evaluations were not included in this work and should be addressed in future studies. Despite these limitations, the present results offer valuable preliminary evidence supporting the topical potential of baricitinib formulations and justify further preclinical and clinical investigations.

This study demonstrates that the choice of petrolatum type has a decisive impact on the properties of topically applied BCT. The results suggest that lipid formulations with liquid petrolatum offer a more suitable profile for topical therapies in psoriasis, favoring local action. This information provides important supporting evidence for the rational design of topical formulations of JAK inhibitors, offering alternatives that could overcome the limitations of oral administration.