Safety Profile of Gestrinone: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

- Population: patients using gestrinone;

- Intervention: gestrinone;

- Comparator: placebo or other active drugs;

- Outcome: side effects of gestrinone;

- Study design: clinical trials, randomized or not.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

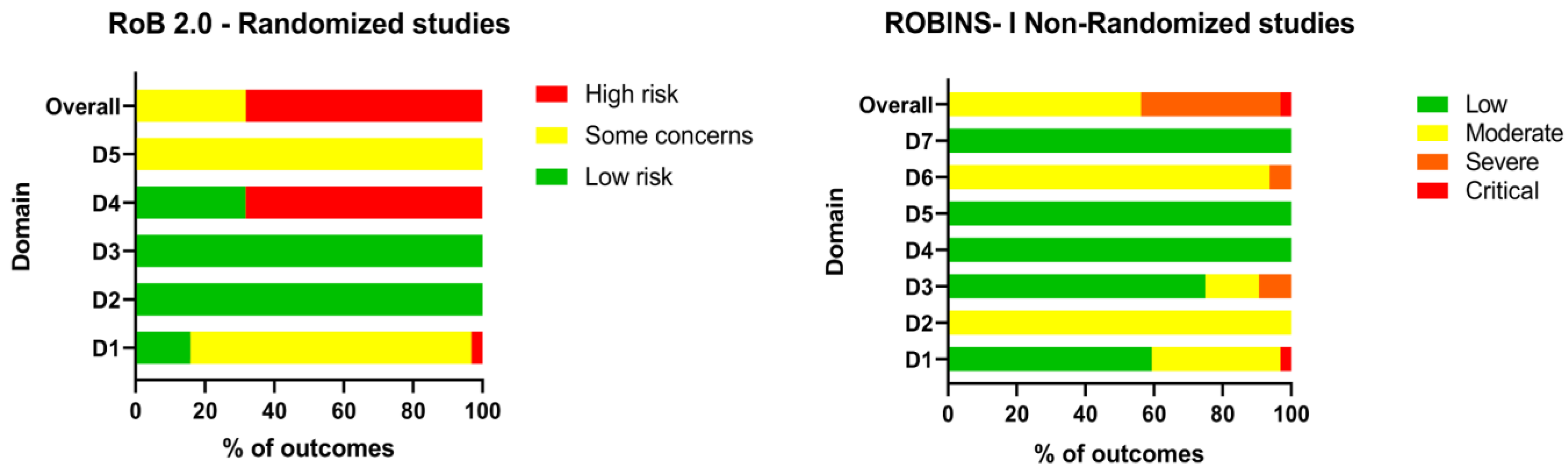

2.3. Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Synthesis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| PubMed | Embase | Web of Science |

|---|---|---|

| gestrinone[MH] OR gestrinone[TIAB] OR ‘r2323’[TIAB] OR dimetriose[TIAB] OR nemestran[TIAB] OR ethylnorgestrienone[TIAB] | ‘gestrinone‘/exp OR gestrinone:ab,ti OR r2323:ab,ti OR dimetriose:ab,ti OR nemestran:ab,ti OR ethylnorgestrienone:ab,ti | ALL = (gestrinone OR r2323 OR dimetriose OR nemestran OR ethylnorgestrienone) |

| Total: 308 | Total: 745 | Total: 180 |

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Coutinho, E. Clinical Experience with Implant Contraception. Contraception 1978, 18, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Marca, A.; Giulini, S.; Vito, G.; Orvieto, R.; Volpe, A.; Jasonni, V.M. Gestrinone in the Treatment of Uterine Leiomyomata: Effects on Uterine Blood Supply. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 82, 1694–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadian-Boulanger, G.; Secchi, J.; Laraque, F.; Raynaud, J.P.; Sakiz, E. Action of a Midcycle Contraceptive (R 2323) on the Human Endometrium. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1976, 125, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renke, G.; Antunes, M.; Sakata, R.; Tostes, F. Effects, Doses, and Applicability of Gestrinone in Estrogen-Dependent Conditions and Post-Menopausal Women. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaya, T.; Fujimoto, J.; Watanabe, Y.; Arahori, K.; Okada, H. Gestrinone (R2323) Binding to Steroid Receptors in Human Uterine Endometrial Cytosol. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1986, 65, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Qiu, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.H.; Liu, G.M.; He, G.L.; Jiang, X.R.; Sun, Z.Y.; Cao, L. Effects of Gestrinone on Uterine Leiomyoma and Expression of C-Src in a Guinea Pig Model. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, Y. Gestrinone Combined with Ultrasound-guided Aspiration and Ethanol Injection for Treatment of Chocolate Cyst of Ovary. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2015, 41, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, E.; Chen, G. Mechanism of Emergency Contraception with Gestrinone: A Preliminary Investigation. Contraception 2007, 76, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markiewicz, L.; Hochberg, R.B.; Gurpide, E. Intrinsic Estrogenicity of Some Progestagenic Drugs. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1992, 41, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Pinto, L.P.; Ferrari, G.; dos Santos, I.K.; de Mello Roesler, C.R.; de Mello Gindri, I. Evaluation of Safety and Effectiveness of Gestrinone in the Treatment of Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 307, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, E.M. Treatment of Large Fibroids with High Doses of Gestrinone. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 1990, 30, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.J.; Cooke, I.D. Impact of Gestrinone on the Course of Asymptomatic Endometriosis. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1987, 294, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, C.C.; Fávaro, D.; Gonçalves, I.; Vicini, L.; Felzener, M.C.M. Gestrinona: Efeito “on Label” e “off Label. ” Braz. J. Health Rev. 2024, 7, 7268–7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; ISBN 9780648848820. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.; Glasziou, P.; Del Mar, C.; Bannach-Brown, A.; Stehlik, P.; Scott, A.M. A Full Systematic Review Was Completed in 2 Weeks Using Automation Tools: A Case Study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 121, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromham, D.R.; Booker, M.W.; Rose, G.L.; Wardle, P.G.; Newton, J.R. Updating the Clinical Experience in Endometriosis--the European Perspective. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1995, 102 (Suppl. S12), 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromham, D.R.; Booker, M.W.; Rose, G.L.; Wardle, P.G.; Newton, J.R. A Multicentre Comparative Study of Gestrinone and Danazol in the Treatment of Endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1995, 15, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, F.; Robertson, D.N.; de Oca, V.M.; Sivin, I.; Brache, V.; Faundes, A. Comparative Clinical Trial of the Progestins R-2323 and Levonorgestrel Administered by Subdermal Implants. Contraception 1978, 18, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, I.D.; Thomas, E.J. The Medical Treatment of Mild Endometriosis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1989, 68, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, E.M. Treatment of Endometriosis with Gestrinone (R-2323), a Synthetic Antiestrogen, Antiprogesterone. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1982, 144, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, E.M.; Boulanger, G.A.; Gonçalves, M.T. Regression of Uterine Leiomyomas after Treatment with Gestrinone, an Antiestrogen, Antiprogesterone. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1986, 155, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, E.M.; Azadian-Boulanger, G. Treatment of Fibrocystic Disease of the Breast with Gestrinone, a New Trienic Synthetic Steroid with Anti-Estrogen, Anti-Progesterone Properties. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1984, 22, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, E.M.; Goncalves, M.T. Long-Term Treatment of Leiomyomas with Gestrinone. Fertil. Steril. 1989, 51, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, E.M.; Da Silva, A.R.; Carreira, C.M.; Chaves, M.C.; Adeodato Filho, J. Contraceptive Effectiveness of Silastic: Implants Containing the Progestin R-2323. Contraception 1975, 11, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.S.; Huggins, G.R.; Garcia, C.R.; Busacca, C. A Synthetic Steroid (R2323) as a Once-A-Week Oral Contraceptive. Fertil. Steril. 1979, 31, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.Y.; Obasiolu, C.W.; Ramos, J.; Khan-Dawood, F.S. Clinical, Endocrine, and Metabolic Effects of Two Doses of Gestrinone in Treatment of Pelvic Endometriosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 176, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, S.; Pavez, M.; Quinteros, E.; Robertson, D.N.; Croxatto, H.B. Clinical Trial with Subdermal Implants of the Progestin R-2323. Contraception 1977, 16, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, L.; Bianchi, S.; Viezzoli, T.; Arcaini, L.; Candiani, G.B. Gestrinone versus Danazol in the Treatment of Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1989, 51, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, K.L.; Thomas, F.J. Tissue and Endocrine Responses to Gestrinone and Danazol in the Treatment of Endometriosis. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 1993, 5, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornstein, M.D.; Gleason, R.E.; Barbieri, R.L. A Randomized Double-Blind Prospective Trial of Two Doses of Gestrinone in the Treatment of Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1990, 53, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppila, A.; Isomaa, V.; Ronnberg, L.; Vierikko, P.; Vihko, R. Effect of Gestrinone in Endometriosis Tissue and Endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 1985, 44, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, G.B.; Mais, V.; Paoletti, A.M.; Ajossa, S.; Guerreiro, S.; Fioretti, P. Efficacy and Endocrine Effects of Medical Treatment of Endometriosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1991, 622, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A.; Tacuri, C.; Serra, M.; Keller, J.; Cortés-Prieto, J. Evaluation of Gestrinone after Surgery in Treatment of Endometriosis. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 1997, 43, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, F.; Stein, R.C.; Coombes, R.C.; Gazet, J.-C.; Ford, H.T.; Rawson, N.S.B. Gestrinone in Mastalgia: A Randomized Double Blind Placebo Controlled Trial. Breast 1994, 3, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L. Clinical Comparison of Mifepristone and Gestrinone for Laparoscopic Endometriosis. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 31, 2197–2202. [Google Scholar]

- Triolo, O.; De Vivo, A.; Benedetto, V.; Falcone, S.; Antico, F. Gestrinone versus Danazol as Preoperative Treatment for Hysteroscopic Surgery: A Prospective, Randomized Evaluation. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 85, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.C.; Rebs, M.C.P. Gestrinone in the Treatment of Menorrhagia. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1990, 97, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, P.L.; Bertolini, S.; Brunenghi, M.C.M.; Daga, A.; Fasce, V.; Marcenaro, A.; Cimato, M.; De Cecco, L. Endocrine, Metabolic, and Clinical Effects of Gestrinone in Women with Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1989, 52, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellini, P.; Soma, M.; Moro, G.L. Gestrinone versus a Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist for the Treatment of Pelvic Pain Associated with Endometriosis: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Gestrinone Italian Study Group. Fertil. Steril. 1996, 66, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Dong, J.; Cong, J.; Wang, C.; Vonhertzen, H.; Godfrey, E.M. Gestrinone Compared With Mifepristone for Emergency Contraception: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Liu, M.; Hao, W.; Li, Y. Clinical Evaluation of Laparoscopic Surgery Combined with Triptorelin Acetate in Patients with Endometriosis and Infertility. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.L.; Yu, N.; Wang, J.; Hao, W.J.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.Y. Therapeutic Effects of Mifepristone Combined with Gestrinone on Patients with Endometriosis. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 32, 1268–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-X.; Ma, W.-G.; Qu, F.; Ma, B.-Z. Comparative Study on the Efficacy of Yiweining and Gestrinone for Post-Operational Treatment of Stage III Endometriosis. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2006, 12, 218–220. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, F. Multicentre Study of Gestrinone in Cyclical Breast Pain. Lancet 1992, 339, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, E.M.; Azadian-Boulanger, G. Treatment of Endometriosis by Vaginal Administration of Gestrinone. Fertil. Steril. 1988, 49, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, L.C.G.; Parente, A.V.; Parente, A.M.V.; Silva, E.S.; das Neves, N.N.S.; de Souza, C.D.; de Morais, W.M.; Silva, M.S.A.d.S.e.; Vaca, A.H.; de Andrade, M.C.; et al. Hormonal Implants, Beauty Chip: Benefits and Harmful. Int. J. Health Sci. 2024, 4, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagoe, D.; Molde, H.; Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T.; Pallesen, S. The Global Epidemiology of Anabolic-Androgenic Steroid Use: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression Analysis. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, A.; Anawalt, B.D. Androgenic Steroids Use and Abuse. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 49, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabology. Position of the Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism on the Use of Anabolic Steroids and Similar for Aesthetic Purposes or to Gain Performance Sports. Available online: https://www.endocrino.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Posicionamento-da-SBEM-Anabolizantes.docx.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Kicman, A.T. Pharmacology of Anabolic Steroids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Vallejo, L. Current Use and Abuse of Anabolic Steroids. Actas Urológicas Españolas (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 44, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Residual Drug in Transdermal and Related Drug Delivery Systems. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/residual-drug-transdermal-and-related-drug-delivery-systems (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Febrasgo. Available online: https://www.febrasgo.org.br/pt/noticias/item/1362-posicionamento-sobre-gestrinona-da-comissao-nacional-especializada-em-endometriose-da-febrasgo-sociedade-brasileira-de-endometriose-e-cirurgia-minimamente-invasiva (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Buhl, L.F.; Christensen, L.L.; Diederichsen, A.; Lindholt, J.S.; Kistorp, C.M.; Glintborg, D.; Andersen, M.; Frystyk, J. Impact of Androgenic Anabolic Steroid Use on Cardiovascular and Mental Health in Danish Recreational Athletes: Protocol for a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Cohort Study as a Part of the Fitness Doping in Denmark (FIDO-DK) Study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e078558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, G.; Van Hout, M.C.; Teck, J.T.W.; McVeigh, J. Treatments for People Who Use Anabolic Androgenic Steroids: A Scoping Review. Harm Reduct. J. 2019, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayama, G.; Brower, K.J.; Wood, R.I.; Hudson, J.I.; Pope, H.G. Anabolic-Androgenic Steroid Dependence: An Emerging Disorder. Addiction 2009, 104, 1966–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olchowska-Kotala, A.; Uchmanowicz, I.; Szczepanowski, R. Verbal Descriptors of the Frequency of Side Effects: Implementation of EMA Recommendations in Patient Information Leaflets in Poland. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2022, 34, mzac013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siewe, N.; Friedman, A. Osteoporosis Induced by Cellular Senescence: A Mathematical Model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseltine, K.N.; Chukir, T.; Smith, P.J.; Jacob, J.T.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Farooki, A. Bone Mineral Density: Clinical Relevance and Quantitative Assessment. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Anti-Doping Agency. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/prohibited-list (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Ministério da Saúde; Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária; 4a Diretoria/Gerência-Geral de Inspeção e Fiscalização Sanitária. Resolução-Re No 4.768, de 22 de Dezembro de 2021. Diário Of. Da União 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vannuccini, S.; Clemenza, S.; Rossi, M.; Petraglia, F. Hormonal Treatments for Endometriosis: The Endocrine Background. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regidor, P.-A. The Clinical Relevance of Progestogens in Hormonal Contraception: Present Status and Future Developments. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 34628–34638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entidades de Fiscalização do Exercício das Profissões Liberais; Conselho Federal de Medicina. Resolução CFM N° 2.333, de 30 de Março de 2023. Diário Of. Da União 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grünewald, S. ‘Chip da Beleza’ Traz Riscos Sem Garantia de Benefício. Available online: https://portugues.medscape.com/verartigo/6510523?form=fpf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

| Authors (year) | Aim | Funding | Conflict of Interest | Setting | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Alvarez et al., 1978) [22] | Contraception | Yes | NR | Multicenter | Randomized, without blinding information |

| (Bromham et al., 1995) [20,21] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | Multicenter | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Cooke & Thomas, 1989) [23] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | NR | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Coutinho, 1982) [24] | Endometriosis treatment | Yes | NR | Unicenter | Single arm trial |

| (Coutinho, 1990) [11] | Uterine leyomas treatment | NR | NR | NR | Single arm trial |

| (Coutinho & Azadian-Boulanger, 1988) [49] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | Unicenter | Single arm trial |

| (Coutinho & Azadian-Boulanger, 1984) [26] | Fibrocystic disease treatment | Yes | NR | NR | Single arm trial |

| (Coutinho et al., 1986) [25] | Uterine leyomas treatment | NR | NR | NR | Randomized, without blinding information |

| (Coutinho EM et al., 1975) [28] | Contraception | Yes | NR | NR | Single arm trial |

| (Coutinho & Goncalves, 1989) [27] | Uterine leyomas treatment | Yes | NR | NR | Randomized, without blinding information |

| (David et al., 1979) [29] | Contraception | NR | NR | NR | Single arm trial |

| (Dawood et al., 1997) [30] | Endometriosis treatment | Yes | NR | Unicenter | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Diaz et al., 1977) [31] | Contraception | Yes | NR | NR | Single arm trial |

| (Fedele et al., 1989) [32] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | NR | Randomized, without blinding information |

| (Forbes & Thomas, 1993) [33] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | NR | Open-label |

| (Hornstein et al., 1990) [34] | Endometriosis treatment | Yes | NR | Unicenter | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Kauppila et al., 1985) [35] | Endometriosis treatment | Yes | NR | NR | Single arm trial |

| (Melis et al., 1991) [36] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | NR | Randomized, without blinding information |

| (Nieto et al., 1997) [37] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | Unicenter | Randomized, without blinding information |

| (Peters, 1992) [48] | Mastalgia | NR | NR | Multicenter | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Azadian-Boulanger et al., 1976) [3] | Contraception | NR | NR | Unicenter | Single arm trial |

| (Song et al., 2018) [39] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | Unicenter | Randomized, without blinding information |

| (Peters et al., 1994) [38] | Mastalgia | NR | NR | Unicenter | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Thomas & Cooke, 1987) [12] | Endometriosis treatment | Yes | NR | NR | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Triolo et al., 2006) [40] | Preoperative endometrial preparation | NR | NR | NR | Randomized, open-label |

| (Turnbull & Rebs, 1990) [41] | Menorrhagia treatment | NR | NR | Unicenter | Randomized, single-blind |

| (Venturini et al., 1989) [42] | Endometriosis treatment | NR | NR | NR | Single arm trial |

| (Vercellini et al., 1996) [43] | Pelvic pain associated with endometriosis | Yes | NR | Multicenter | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Wu et al., 2010) [44] | Contraception | Yes | NR | Multicenter | Randomized, double-blind |

| (Xue et al., 2016) [46] | Endometriosis treatment | No | No | Unicenter | Randomized, single-blind |

| (Xue et al., 2018) [45] | Endometriosis treatment | No | No | Unicenter | Randomized, without blinding information |

| (Yang et al., 2006) [47] | Endometriosis treatment | Yes | NR | NR | Randomized, without blinding information |

| Interventions | Pharmacological Classification | (%) of Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Gestrinone | Progestin | 2403 (64.16%) |

| Levonorgestrel | Progestin | 52 (1.39%) |

| Danazol | Synthetic androgen | 244 (6.51%) |

| Buserelin | GnRH agonists | 28 (0.75%) |

| Placebo | Inactive substance | 164 (4.38%) |

| Mifepristone | Antiprogestin | 683 (18.24%) |

| Control | - | 73 (1.95%) |

| Triptorelin | GnRH agonists | 50 (1.33%) |

| Leuprolide acetate | GnRH agonists | 28 (0.75%) |

| Yiweining | Herbal medicine | 20 (0.53%) |

| Total number of patients | - | 3745 (100%) |

| Authors (Year) | Intervention | N | Route of Administration | Dose | Dosage | Duration of Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Alvarez et al., 1978) [22] | Gestrinone | 48 | Subdermal | 30.1 ± 1.2 mg | - | 504.2 months |

| Levonorgestrel | 52 | Subdermal | 29.7 ± 0.9 mg/33.9 ± 0.7 mg | - | 512.5 months | |

| (Bromham et al., 1995) [20,21] | Gestrinone | 132 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| Danazol | 137 | Oral | 200 mg | Twice daily | 6 months | |

| (Cooke & Thomas, 1989) [23] | Gestrinone | 18 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| Placebo | 17 | Oral | - | Twice weekly | 6 months | |

| (Coutinho, 1982) [24] | Gestrinone | 20 | Oral | 5 mg | Twice weekly | A period of 6 to 8 months |

| (Coutinho, 1990) [11] | Gestrinone | 24 | Oral | 5 mg | Three times weekly | A period of 6 to 1 year |

| (Coutinho & Azadian-Boulanger, 1988) [49] | Gestrinone | 17 | Vaginal | 2.5 mg | Three times weekly | 6 months |

| Gestrinone | 30 | Vaginal | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 7 months | |

| Gestrinone | 30 | Vaginal | 5 mg | Twice weekly | 8 months | |

| Gestrinone | 27 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 9 months | |

| (Coutinho & Azadian-Boulanger, 1984) [26] | Gestrinone | 28 | Oral | 5 mg | Twice weekly | 3–9 months |

| (Coutinho et al., 1986) [25] | Gestrinone | 34 | Oral | 5 mg | Twice weekly | 4 months |

| Gestrinone | 36 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Three times weekly | 4 months | |

| Gestrinone | 27 | Vaginal | 2.5 mg | Three times weekly | 4 months | |

| (Coutinho EM et al., 1975) [28] | Gestrinone | 98 | Subdermal | 30–40 mg | 2 implants | 9 months |

| Gestrinone | 180 | Subdermal | 30–40 mg | 3 implants | 9 months | |

| Gestrinone | 181 | Subdermal | 30–40 mg | 4 implants | 9 months | |

| Gestrinone | 68 | Subdermal | 30–40 mg | 5 implants | 9 months | |

| (Coutinho & Goncalves, 1989) [27] | Gestrinone | 41 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Three times weekly | 3 months |

| Gestrinone | 31 | Oral | 5.0 mg | Three times weekly | 3 months | |

| (David et al., 1979) [29] | Gestrinone | 28 | Vaginal | 5.0 mg | Three times weekly | 3 months |

| Gestrinone | 28 | Oral | 5.0 mg | Once weekly | 3 months | |

| (Dawood et al., 1997) [30] | Gestrinone | 5 | Oral | 1.25 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| Gestrinone | 6 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months | |

| (Diaz et al., 1977) [31] | Gestrinone | 38 | Subdermal | 30.91 ± 1.19 mg | - | - |

| (Fedele et al., 1989) [32] | Gestrinone | 20 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| Danazol | 19 | Oral | 600 mg | Once daily | 6 months | |

| (Forbes & Thomas, 1993) [33] | Gestrinone | 12 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 24 weeks |

| Danazol | 11 | Oral | 400 and 800 mg | Once daily | 24 weeks | |

| (Hornstein et al., 1990) [34] | Gestrinone | 6 | Oral | 1.25 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| Gestrinone | 6 | Oral | 2.25 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months | |

| (Kauppila et al., 1985) [35] | Gestrinone | 11 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | - |

| (Melis et al., 1991) [36] | Gestrinone | 10 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| Danazol | 10 | Oral | 200 mg | Three times daily | 6 months | |

| Buserelin | 10 | Subcutaneously | 300 ug | Three times daily | 6 months | |

| (Nieto et al., 1997) [37] | Gestrinone | 25 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| Buserelin | 18 | Intranasal | 300 ugrs | Three times daily | 6 months | |

| (Peters, 1992) [48] | Gestrinone | 73 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 3 months |

| Placebo | 72 | Oral | - | - | 3 months | |

| (Azadian-Boulanger et al., 1976) [3] | Gestrinone | 181 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Once weekly | 2 to 44 months |

| (Song et al., 2018) [39] | Mifepristone | 60 | Oral | 10 mg | Once daily | 6 months |

| Gestrinone | 60 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months | |

| Control | 60 | - | - | - | ||

| (Peters et al., 1994) [38] | Gestrinone | 38 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 3 months |

| Placebo | 40 | Oral | - | Twice weekly | 3 months | |

| (Thomas & Cooke, 1987) [12] | Gestrinone | 18 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 24 weeks |

| Placebo | 17 | Oral | - | Twice weekly | 24 weeks | |

| (Triolo et al., 2006) [40] | Danazol | 67 | Oral | 200 mg | Three times daily | 4 or 5 weeks |

| Gestrinone | 69 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 5 or 5 weeks | |

| (Turnbull & Rebs, 1990) [41] | Gestrinone | 19 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 12 weeks |

| Placebo | 18 | Oral | - | - | - | |

| (Venturini et al., 1989) [42] | Gestrinone | 11 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| (Vercellini et al., 1996) [43] | Gestrinone | 27 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months |

| IM LA | 28 | Intramuscular | 3.75 mg | Every 4 weeks | 6 months | |

| (Wu et al., 2010) [44] | Gestrinone | 498 | Oral | 2.5 mg | NR | NR |

| Mifepristone | 498 | Oral | 2.5 mg | NR | NR | |

| (Xue et al., 2016) [46] | Triptorelin | 50 | Intramuscular | 3.75 mg | Once month | 3 months |

| Gestrinone | 50 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 6 months | |

| Mifepristone | 50 | Oral | 25 mg | Twice daily | 3 months | |

| (Xue et al., 2018) [45] | Gestrinone | 75 | Oral | 2.5 mg | Twice weekly | 24 weeks |

| Human Body System | Pharmacological Classification | (%) of Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Nervous system | Headache | 142/1274 (11.15%) |

| Nausea | 153/1054 (14.52%) | |

| Dizziness | 73/804 (9.08%) | |

| Nervousness | 29/399 (7.27%) | |

| Depression | 6/150 (4.00%) | |

| Endocrine system | Hirsutism | 118/1037 (11.38%) |

| Acne and seborrhea | 111/260 (42.69%) | |

| Chloasma | 7/302 (2.32%) | |

| Female reproductive system | Amenorrhea | 104/251 (41.43%) |

| Increased libido | 30/249 (12.05%) | |

| Decreased libido | 61/230 (26.52%) | |

| Hot flushes | 85/346 (24.57%) | |

| Abdominal pain | 69/900 (7.67%) | |

| Others | Hoarseness | 31/887 (3.49%) |

| Cramps | 66/355 (18.59%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fagundes, V.L.; Barreiro Marques, N.C.; Franco de Lima, A.; de Fátima Cobre, A.; Stumpf Tonin, F.; Luna Lazo, R.E.; Pontarolo, R. Safety Profile of Gestrinone: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17050638

Fagundes VL, Barreiro Marques NC, Franco de Lima A, de Fátima Cobre A, Stumpf Tonin F, Luna Lazo RE, Pontarolo R. Safety Profile of Gestrinone: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(5):638. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17050638

Chicago/Turabian StyleFagundes, Vitor Luis, Nathália Carolina Barreiro Marques, Amanda Franco de Lima, Alexandre de Fátima Cobre, Fernanda Stumpf Tonin, Raul Edison Luna Lazo, and Roberto Pontarolo. 2025. "Safety Profile of Gestrinone: A Systematic Review" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 5: 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17050638

APA StyleFagundes, V. L., Barreiro Marques, N. C., Franco de Lima, A., de Fátima Cobre, A., Stumpf Tonin, F., Luna Lazo, R. E., & Pontarolo, R. (2025). Safety Profile of Gestrinone: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceutics, 17(5), 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17050638