Evaluating and Managing the Microbial Contamination of Eye Drops: A Two-Phase Hospital-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

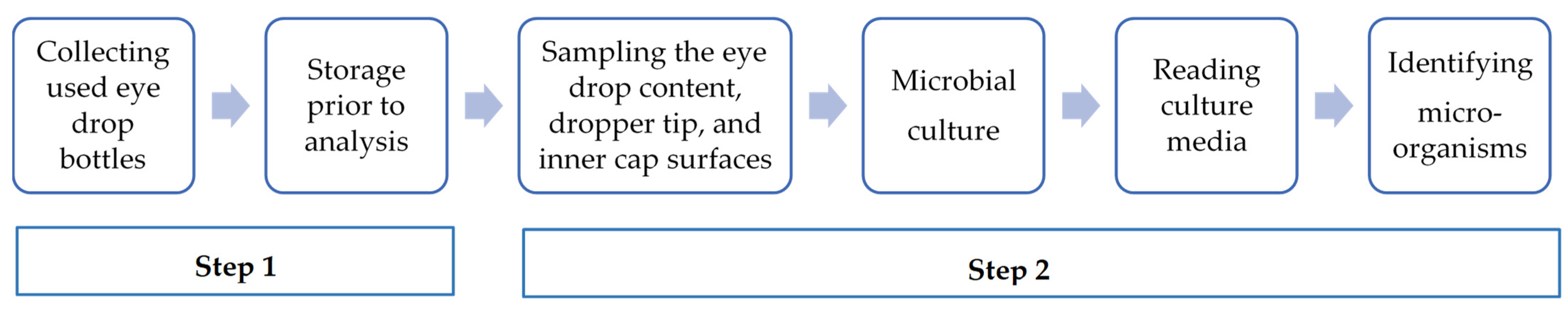

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Phase 1: The Assessment of the Microbial Contamination of In-Use Eye Drop Content and Dropper Tip and Inner Cap Surfaces

- This study was conducted collaboratively between the Ophthalmology Services and the Pharmacy Unit (PU)—UPSO2.

- The storage temperature of collected eye drops was between +2 and +8 °C for a maximum of 48 h before analysis.

- The information recorded for each eye drop included the collection date, active ingredient, batch number, source, packaging type, storage conditions during use, indication, and duration of treatment.

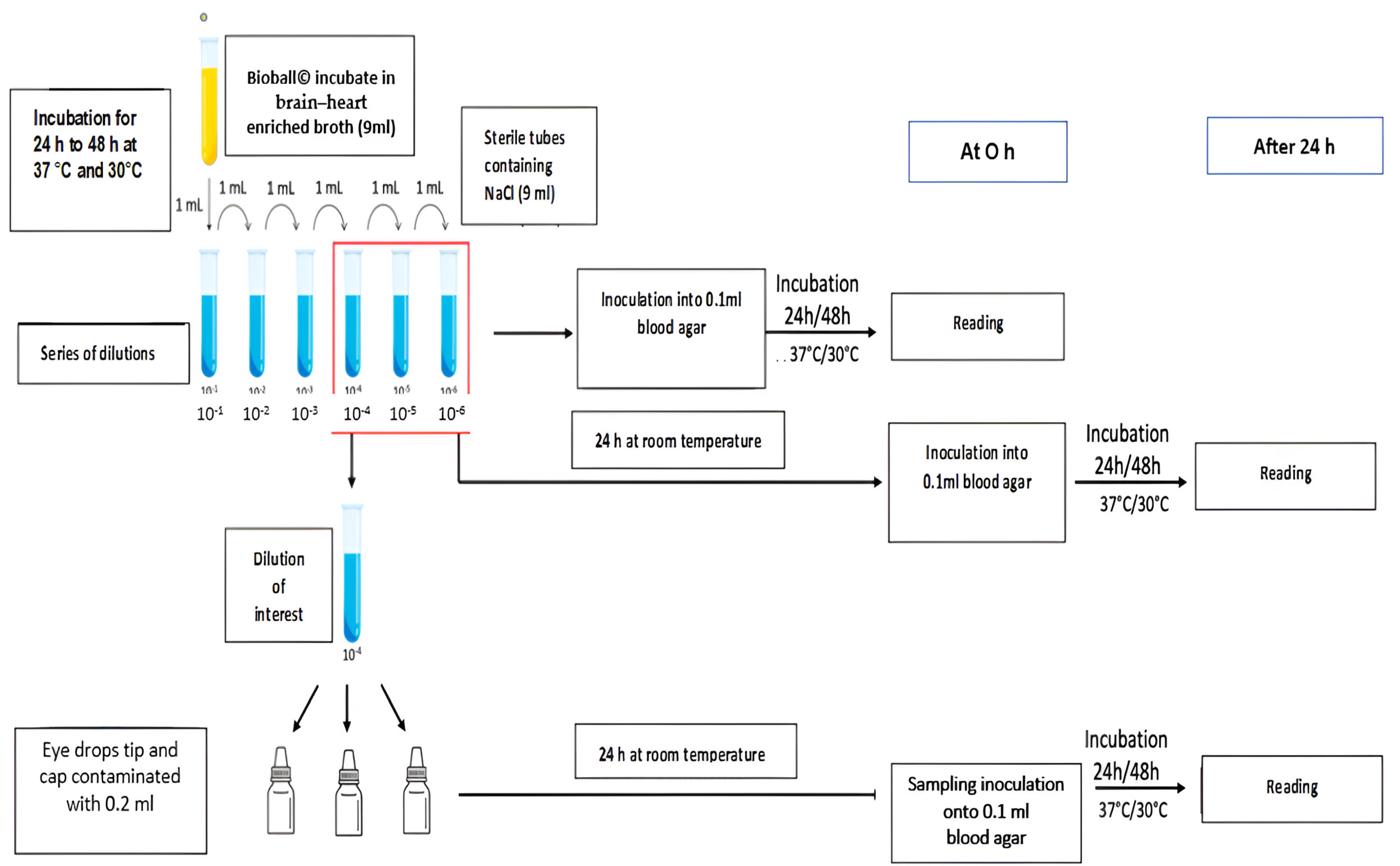

Validating the Assay Conditions

- The selection of microbial contaminants

- Gram-positive cocci: Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 10788);

- Gram-negative bacilli: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (NCTC 12924);

- Fungi: Candida albicans (NCPF 3179).

- b.

- Establishing the number of microorganisms necessary for contamination

- c.

- Microbial contamination of the dropper tip and inner cap of sterile eye drops

- -

- Volumes of 0.2 mL of the selected dilution, 10−4, were deposited on the inner surface of eye drop caps.

- -

- The eye drop bottles were positioned upside down to bring the eye drop tips into contact with the suspension by immersion.

- -

- The eye drop bottles were then repositioned upright to evenly distribute the suspension over the entire surface of the tips and caps.

- -

- Finally, the eye drop bottles were placed horizontally and rolled on the bench.

- -

- The eye drop bottles were incubated upright for 24 h at room temperature.

- Inoculated (0.1 mL) at H0 onto blood agar plates. These were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa and for 48 h for C. albicans, and they were then analyzed to enumerate the microorganisms (MO) in the dilution of interest.

- Incubated for 24 h at room temperature and then inoculated (0.1 mL) onto blood agar plates. These were in turn incubated for 24 h at 37 °C for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa and for 48 h for C. albicans, and they were then analyzed to enumerate the MOs in the dilution of interest after 24 to 48 h in 0.9% NaCl.

- d.

- Sampling and culturing the eye drop tips and inner caps

- -

- The excess solution in the caps was removed after 24 h of contact with the indicated microorganism.

- -

- The eye drop tips and inner caps were swabbed separately using eSwab® (Deltalab, Spain).

- -

- The agar plates were inoculated by direct inoculation from the swab, which was spread over the entire surface; then, the swab was turned by 90° and spread a second time by turning the Petri dish 90°.

- -

- The blood agar plates were incubated for three days at 37 °C for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa and at 30 °C for C. albicans.

Collection and Culture of In-Use Specimens

- Identification of Microorganisms by MALDI-TOF-MS

- b.

- Evaluation of Residual Content Contamination

2.1.2. Phase 2: Evaluation of the Practical and Antimicrobial Properties of the Pylote SAS Antimicrobial Technology

Validation of the Practical Application of Activated Rispharm™

- -

- Activated Rispharm™ Eye Drops: Practical Evaluation

- -

- The Production of a Batch of Eye Drops in an Isolator: For the production of eye drops in the isolator, the operators had to evaluate the following:

- The adaptability of the bottleneck to the filling process.

- The attachment of the dropper tip to the eye drop container.

- The capping procedure.

- -

- Inspection and Packaging: For the inspection and control of organoleptic characteristics, operators were asked to verify that the bottles were transparent enough to allow the detection of any non-conformities (clarity, absence of particles, color, volume).

- -

- Concerning labeling and packaging, they had to ensure the absence of significant malfunctions on the labeling lines and verify the suitability of the eye drop bottle size for the size of the eye drop boxes used by UPSO2 for secondary packaging.

- -

- Practical Use: A drop was extracted from the eye drops every hour for several consecutive hours to replicate patient use. This administration pattern corresponds to enhanced antibiotic eye drop treatments that must be administered every hour for an average of 2 to 3 days or longer, depending on the severity of the infection.

- -

- Other evaluated aspects included the flexibility of the bottle during manipulation, the consistency of delivered drops, and changes in or issues with the eye drops during use.

Validation of the Antimicrobial Properties of Activated Rispharm™

- -

- Group 1: 3 standard packaging vs. 3 Activated Rispharm™ packaging contaminated with 105 CFU of S. aureus.

- -

- Group 2: 3 standard packaging vs. 3 Activated Rispharm™ packaging contaminated with 105 CFU of P. aeruginosa.

- -

- Group 3: 3 standard packaging vs. 3 Activated Rispharm™ packaging contaminated with 103 CFU of C. albicans.

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Assessment of Microbiological Contamination In-Use Eye Drops

3.1.1. Validation of Sampling and Culture Methods

3.1.2. Collection and Culture of In-Use Specimens

Contamination Rate and Characteristics of Contaminated Bottles

Number of Microorganisms Recovered from Eye Drop Tip and Inner Cap

- -

- The three contaminated eye drop tips and inner caps used during hospitalization had a microbial load of less than 10 CFU.

Isolated Microorganisms

- -

- The identified microorganisms included commensal germs from the environment and human skin flora. The used eye drops collected from the hospital and patients showed microbial contamination of the eye drop tips and caps with Staphylococcus epidermidis and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. All other detected microorganisms originated only from patients using eye drops. The most frequently detected microorganisms from used eye drop tips and caps were Gram-positive bacteria (GPB), such as Micrococcus luteus (n = 14) and other GPB considered part of the skin flora, including Staphylococcus hominis (n = 5), Staphylococcus capitis (n = 4), Kocuria species (n = 6), Staphylococcus aureus (n = 3), Staphylococcus haemolyticus (n = 3), Staphylococcus warneri (n = 2), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (n = 2), Staphylococcus auricularis (n = 1), Staphylococcus pasteuri (n = 1), Corynebacterium species (n = 2), Microbacterium aurum (n = 2), Aerococcus viridans (n = 1), and Dolosigranulum pigrum (n = 1). Isolated GPB found in the environment included Bacillus cereus (n = 2), Bacillus thuringiensis (n = 1), Bacillus licheniformis (n = 1), Janibacter hoylei (n = 2), Lysinibacillus spp. (n = 1), and Streptomyces violaceoruber (n = 1). Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) contaminants included Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n = 3), Moraxella osloensis (n = 2), Pseudomonas oryzihabitans (n = 1), Acinetobacter lwoffii (n = 1), and Roseomonas mucosa (n = 4). Sterility tests showed only one positive result (in-use eye drop bottle collected from a patient) involving the eye drop tip and inner cap contaminated with Candida parapsilosis (n = 1). The residual content’s microbial contaminants were Candida parapsilosis and Lysinibacillus spp. (n = 1).

3.2. Phase 2: Evaluation of the Practical and Antimicrobial Properties of Pylote SAS Antimicrobial Technology

3.2.1. Validation of the Practical Application of Activated Rispharm™

- -

- Use of Activated Rispharm™: Minor discrepancies were noted compared to the bottles routinely used. There were no significant differences in the bottleneck size or its adaptability to the filling process. Operators unanimously acknowledged the challenge of inserting the dropper tip. The operators recommended the implementation of a more robust capping procedure to ensure secure bottle closure, with a particular focus on addressing any vacuum occurrence before the final screwing movement.

- -

- Three different operators were involved in evaluating (1) the organoleptic characteristics, (2) labeling, and (3) packaging with Activated Rispharm™ packaging. One operator raised concerns about the space between the cap ring and the bottle body, which may affect the proper closure of the bottles. All operators faced labeling issues because of the width of the Activated Rispharm™ bottles and the parameters of the labeling machine. There were no difficulties with the secondary packaging.

- -

- Three pharmacists were assigned to simulate the administration of compounded eye drops. They all agreed on the flexibility of the Activated Rispharm™ bottles and the dispensing of drops. The Activated Rispharm™ bottles were described as flexible, providing a good grip and allowing the formation of drops with a reproducible volume and controlled administration frequency. The bottle shape during use demonstrated no changes, such as observed deformities, after emptying the bottle.

3.2.2. Validation of the Antimicrobial Properties of Pylote SAS Antimicrobial Technology

- -

- For S. aureus, the standard packaging showed CFU counts higher than the detection limit (3.3 × 103 CFU) 24 h after the cap and insert inoculation. In the same conditions, the agar plates from Pylote packaging showed a countable average of 2.1 × 102 CFU. A difference in the reduction of above 1.2 log in favor of Pylote packaging was observed compared to standard packaging.

- -

- For P. aeruginosa, standard packaging also showed CFU counts higher than the detection limit (3.3 × 103 CFU) 24 h after the cap and insert inoculation. Agar plate counts from PyloteTM showed 3.2 × 102 CFU on average, leading to a reduction higher than 1 log.

- -

- For C. albicans, both packaging types showed similar microbial loads: 3.0 × 102 CFU for standard packaging and 2.4 × 102 CFU for PyloteTM packaging.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| S. aureus | P. aeruginosa | C. albicans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inoculated number at 0 h | Detected number after 24 h contact time | Inoculated number at 0 h | Detected number after 24 h contact time | Inoculated number at 0 h | Detected number after 24 h contact time | |

| Bottle 1 | 103 CFU | 6.5 × 102 CFU | 103 CFU | 1.1 × 102 CFU | 102 CFU | 1.7 × 101 CFU |

| Bottle 2 | 4.6 × 102 CFU | 3.6 × 102 CFU | 2.2 × 101 CFU | |||

| Bottle 3 | 5.6 × 102 CFU | 2.0 × 102 CFU | 1.6 × 101 CFU | |||

| Mean ± SD | 5.6 × 102 CFU ± 9.55 × 101 CFU | 2.2 × 102 CFU ± 1.3 × 102 CFU | 1.8 × 101 CFU ± 0.3 × 101 CFU | |||

References

- Burton, M.J.; Ramke, J.; Marques, A.P.; Bourne, R.R.; Congdon, N.; Jones, I.; Tong, B.A.M.A.; Arunga, S.; Bachani, D.; Bascaran, C.; et al. The Lancet global health Commission on global eye health: Vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e489–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Blindness and Vision Impairment. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Fricke, T.R.; Tahhan, N.; Resnikoff, S.; Papas, E.; Burnett, A.; Ho, S.M.; Naduvilath, T.; Naidoo, K.S. Global prevalence of presbyopia and vision impairment from uncorrected presbyopia: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.M.; Kombo, N.; Teng, C.C.; Mruthyunjaya, P.; Nwanyanwu, K.; Parikh, R. Ophthalmic medication expenditures and out-of-pocket spending: An analysis of United States prescriptions from 2007 through 2016. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 1292–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watane, A.; Kalavar, M.; Reyes, J.; Yannuzzi, N.A.; Sridhar, J. The Effect of Market Competition on the Price of Topical Eye Drops. In Seminars in Ophthalmology; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022; Volume 37, pp. 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederkorn, J.Y. Dynamic immunoregulatory processes that sustain immune privilege in the eye. In Encyclopedia of the Eye; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Teweldemedhin, M.; Gebreyesus, H.; Atsbaha, A.H.; Asgedom, S.W.; Saravanan, M. Bacterial profile of ocular infections: A systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, K.; Marchin, L.; Kodjikian, L.; Rocher, M.; Roques, C. Highlighting the microbial contamination of the dropper tip and cap of in-use eye drops, the associated contributory factors, and the risk of infection: A past-30-years literature review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, P.J.; Ong, B.; Stanley, C.B. Contamination of diagnostic ophthalmic solutions in primary eye care settings. Mil. Med. 1997, 162, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razooki, R.A.; Saeed, E.N.; Al-Deem, H.I.O. Microbial Contamination of Eye Drops in out Patient in Iraq. Iraqi J. Pharm. Sci 2011, 20, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachewar, N.P.; Deshmukh, D.; Choudhari, S.R.; Joshi, R.S. Evaluation of used eye drop containers for microbial contamination in outpatient department of tertiary care teaching hospital. Int. J. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 7, 2319-2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chua, S.W.; Mustapha, M.; Wong, K.K.; Ami, M.; Mohd Zahidin, A.Z.; Nasaruddin, R.A. Microbial contamination of extended use ophthalmic drops in ophthalmology clinic. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 2021, 3147–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, S.; France, D.; Asiedu, K. Microbial contamination of multiple-use bottles of fluorescein ophthalmic solution. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2019, 102, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrat, L.; Gelaw, Y.; Beyene, G.; Gize, A. Microbial contamination and antimicrobial resistance in use of ophthalmic solutions at the Department of Ophthalmology, Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 2019, 5372530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudouin, C.; Labbé, A.; Liang, H.; Pauly, A.; Brignole-Baudouin, F. Preservatives in eyedrops: The good, the bad and the ugly. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2010, 29, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, M.H.; Silva, F.Q.; Blender, N.; Tran, T.; Vantipalli, S. Ocular benzalkonium chloride exposure: Problems and solutions. Eye 2022, 36, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, S.P.; Ahdoot, M.; Marcus, E.; Asbell, P.A. Comparative toxicity of preservatives on immortalized corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 25, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nentwich, M.M.; Kollmann, M.K.; Meshack, M.; Ilako, D.R.; Schaller, U.C. Microbial contamination of multi-use ophthalmic solutions in Kenya. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feghhi, M.; Zarei Mahmoudabadi, A.; Mehdinejad, M. Evaluation of fungal and bacterial contaminations of patient-used ocular drops. Med. Mycol. 2008, 46, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donzis, P.B. Corneal ulcer associated with contamination of aerosol saline spray tip. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1997, 124, 394–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montecalvo, M.A.; Karmen, C.L.; Alampur, S.K.; Kauffman, D.J.H.; Wormser, G.P. Contaminated medicinal solutions associated with endophthalmitis. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 1993, 2, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwal, B.L.; Verma, A.K. Epidemiology of ocular infection due to bacteria and fungus—A prospective study. JK Sci 2008, 10, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, R.J.; Shott, S.; Schatz, S.; Farley, S.J. Association between moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution and fungal infection in patients with corneal ulcers and microbial keratitis. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 25, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton III, W.C.; Eiferman, R.A.; Snyder, J.W.; Melo, J.C.; Raff, M.J. Serratia keratitis transmitted by contaminated eyedroppers. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1982, 93, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, B.L.; Alfonso, E.C.; Miller, D. In-use study of potential bacterial contamination of ophthalmic moxifloxacin. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2005, 31, 1773–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, M.S.; Schlitzer, R.L.; Ward, M.A.; Wilson, L.A.; Ahearn, D.G. Association of Pseudomonas and Serratia corneal ulcers with use of contaminated solutions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1987, 25, 1398–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessner, R.; Golan, S.; Barak, A. Changes in the etiology of endophthalmitis from 2003 to 2010 in a large tertiary medical center. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 24, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasson, P.J.; Boruchoff, S.A.; Schein, O.D.; Kenyon, K.R. Microbial keratitis associated with contaminated ocular medications. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1988, 105, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovanesian, J.; Singh, I.P.; Bauskar, A.; Vantipalli, S.; Ozden, R.G.; Goldstein, M.H. Identifying and addressing common contributors to nonadherence with ophthalmic medical therapy. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 34 (Suppl. S1), S1–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usgaonkar, U.; Zambaulicar, V.; Shetty, A. Subjective and objective assessment of the eye drop instillation technique: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.F.; Paredes, A.F.; Madeira, N.; Moraes, H.V.; Santhiago, M.R. Assessment of eye drop instillation technique in glaucoma patients. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2017, 80, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashiwagi, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Ito, Y.; Kawate, H.; Sakamoto, M.; Obi, S.; Haro, H. Investigation of visual and physical factors associated with inadequate instillation of eyedrops among patients with glaucoma. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Cholkar, K.; Agrahari, V.; Mitra, A.K. Ocular drug delivery systems: An overview. World J. Pharmacol. 2013, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Pharmacopee Europeenne—11eme Edition. Available online: https://www.edqm.eu/en/european-pharmacopoeia-ph.-eur.-11th-edition (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- European Commission. EudraLex—Volume 4—Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines. 2015. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/eudralex/eudralex-volume-4_en (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Alghamdi, E.A.S.; Al Qahtani, A.Y.; Sinjab, M.M.; Alyahya, K.M.; Alghamdi, E.A.S.; Al Qahtani, A.Y.; Sinjab, M.M.; Alyahya, K.M. Guidelines of The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) on Pharmacy-Prepared Ophthalmic Products. In Extemporaneous Ophthalmic Preparations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et Les Produits de Santé. Bonnes-Pratiques-de-Preparation-2023; ANSM, 2023. Available online: https://ansm.sante.fr/uploads/2023/08/02/20230802-bonnes-pratiques-de-preparation-08-2023.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- ISO 10993-10:2021; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices: Part 10: Tests for Skin Sensitization. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75279.html (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- ISO 22196: 2011; Measurement of Antibacterial Activity on Plastics and Other Non-Porous Surfaces. ISO, 2011. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/54431.html#:~:text=ISO%2022196%3A2011%20specifies%20a,products%20(including%20intermediate%20products) (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Membrane Filtration Sterility Test. Merck. Available online: https://www.merckmillipore.com/FR/fr/products/industrial-microbiology/sterilitytesting/membrane-filtration-sterilitytest/F0mb.qB.WsMAAAE_TuF3.Lxi,nav?ReferrerURL=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Chantra, S.; Hathaisaard, P.; Grzybowski, A.; Ruamviboonsuk, P. Microbial contamination of multiple-dose preservative-free hospital ophthalmic preparations in a tertiary care hospital. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2022, 2, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.Q.; Tejwani, D.; Wilson, J.A.; Butcher, I.; Ramaesh, K. Microbial contamination of preservative free eye drops in multiple application containers. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-García, J.S.; García-Lozano, I. Use of containers with sterilizing filter in autologous serum eyedrops. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2225–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saisyo, A.; Oie, S.; Kimura, K.; Sonoda, K.H.; Furukawa, H. Microbial contamination of in-use ophthalmic preparations and its prevention. Bull. Yamaguchi Med. Sch 2016, 63, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Teuchner, B.; Wagner, J.; Bechrakis, N.E.; Orth-Höller, D.; Nagl, M. Microbial contamination of glaucoma eyedrops used by patients compared with ocular medications used in the hospital. Medicine 2015, 94, e583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaw, A.; Tsegaw, A.; Abula, T.; Assefa, Y. Bacterial contamination of multi-dose eye drops at ophthalmology department, University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 24, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, S.; Mensah, R.; Kwakye-Nuako, G.; Abu, E.K. Microbial contamination of topical therapeutic ophthalmic medications in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. Niger. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 27, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, D.J.; Hanlon, G.W.; Dyke, S. Evaluation of an extended period of use for preserved eye drops in hospital practice. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 82, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Daehn, T.; Schneider, A.; Knobloch, J.; Hellwinkel, O.J.; Spitzer, M.S.; Kromer, R. Contamination of multi dose eyedrops in the intra and perioperative context. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harte, V.J.; O’Hanrahan, M.T.; Timoney, R.F. Microbial contamination in residues of ophthalmic preparations. Int. J. Pharm. 1978, 1, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, O.; Bottone, E.J.; Podos, S.M.; Schumer, R.A.; Asbell, P.A. Microbial contamination of medications used to treat glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1995, 79, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fazeli, M.R.; Beheshtnezhad, H.; MEHREGAN, H.; Elahian, L. Microbial contamination of preserved ophthalmic drops in outpatient departments: Possibility of an extended period of use. Daru J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 12, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Figuêiredo, L.V.; Mantovani, C.M.L.; Vianna, M.S.; Fonseca, B.M.; Costa, A.A.A.N.; Mesquita, Y.B.; Polveiro, J.P.d.S.C.; Nassaralla Júnior, J.J. Microbial contamination in eye drops of patients in glaucoma treatment. Rev. Bras. Oftalmol. 2018, 77, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Rahim, N.; Maqbool, T. Bacterial Contamination of Multi-Dose Ophthalmic Drops. Hamdar Med. 2018, 61, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- HØVDING, G.; SJURSEN, H. Bacterial contamination of drops and dropper tips of in-use multidose eye drop bottles. Acta Ophthalmol. 1982, 60, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssens, J.M.; Quintana-Giraldo, C.; Jacques, S.; El-Zoghbi, N.; Lampasona, V.; Langevin, C.; Bouchard, J.F. Shelf life and efficacy of diagnostic eye drops. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2018, 95, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcon, I.; Tam, C.; Mun, J.J.; LeDue, J.; Evans, D.J.; Fleiszig, S.M. Factors impacting corneal epithelial barrier function against Pseudomonas aeruginosa traversal. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, I.U.; Flynn, H.W., Jr.; Feuer, W.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Alfonso, E.C.; Forster, R.K.; Miller, D. Endophthalmitis associated with microbial keratitis. Ophthalmology 1996, 103, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, A.L.; Katz, J.; Covert, D.; Kelly, C.A.; Suan, E.P.; Speicher, M.A.; Sund, N.J.; Robin, A.L. A video study of drop instillation in both glaucoma and retina patients with visual impairment. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 152, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, M.C.; Moussally, K.; Harissi-Dagher, M. Review of endophthalmitis following Boston keratoprosthesis type 1. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 96, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.A.; Sawant, A.D.; Simmons, R.B.; Ahearn, D.G. Microbial contamination of contact lens storage cases and solutions. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1990, 110, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herreras, J.M.; Pastor, J.C.; Calonge, M.; Asensio, V.M. Ocular surface alteration after long-term treatment with an antiglaucomatous drug. Ophthalmology 1992, 99, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.C.H.; Lin, Y.Y.; Kuo, C.N.; Lai, L.J. Cladosporium keratitis—A case report and literature review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Patil, B.; Shah, B.M.; Bali, S.J.; Mishra, S.K.; Dada, T. Evaluating eye drop instillation technique in glaucoma patients. J. Glaucoma 2012, 21, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatham, A.J.; Sarodia, U.; Gatrad, F.; Awan, A. Eye drop instillation technique in patients with glaucoma. Eye 2013, 27, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, G.F.; Hollander, D.A.; Williams, J.M. Evaluation of eye drop administration technique in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2013, 29, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano-Gomez, G.; Castillejos, A.; Kahook, M.; Jimenez-Roman, J.; Gonzalez-Salinas, R. Videographic assessment of glaucoma drop instillation. J. Curr. Glaucoma Pract. 2015, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mehuys, E.; Delaey, C.; Christiaens, T.; Van Bortel, L.; Van Tongelen, I.; Remon, J.P.; Boussery, K. Eye drop technique and patient-reported problems in a real-world population of eye drop users. Eye 2020, 34, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.A.; Sleath, B.; Carpenter, D.M.; Blalock, S.J.; Muir, K.W.; Budenz, D.L. Drop instillation and glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 29, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleath, B.; Blalock, S.; Covert, D.; Stone, J.L.; Skinner, A.C.; Muir, K.; Robin, A.L. The relationship between glaucoma medication adherence, eye drop technique, and visual field defect severity. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 2398–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayner, R.; Carpenter, D.M.; Robin, A.L.; Blalock, S.J.; Muir, K.W.; Vitko, M.; Hartnett, M.E.; Lawrence, S.D.; Giangiacomo, A.L.; Tudor, G.; et al. How glaucoma patient characteristics, self-efficacy and patient–provider communication are associated with eye drop technique. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 24, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoda, M.; Yamabayashi, S.; Furuta, M.; Tsukahara, S. Do glaucoma patients use eye drops correctly? J. Glaucoma 1995, 4, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmin, A.; Syre, H.; Ushakova, A.; Utheim, T.P.; Forsaa, V.A. Twenty years of endophthalmitis: Incidence, aetiology and clinical outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, e62–e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Páez, L.A.; Zenteno, J.C.; Alcántar-Curiel, M.D.; Vargas-Mendoza, C.F.; Rodríguez-Martínez, S.; Cancino-Diaz, M.E.; Jan-Roblero, J.; Cancino-Diaz, J.C. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from healthy conjunctiva and a comparative analysis with isolates from ocular infection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediero, S.; de Los Bueis, A.B.; Spiess, K.; Díaz-Almirón, M.; del Hierro Zarzuelo, A.; Rodes, I.V.; Perea, A.G. Clinical and microbiological profile of infectious keratitis in an area of Madrid, Spain. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 36, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Kitazawa, K.; Deguchi, H.; Sotozono, C. Current evidence for Corynebacterium on the ocular surface. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattern, R.M.; Ding, J. Keratitis with Kocuria palustris and Rothia mucilaginosa in vitamin A deficiency. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2014, 5, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasudha, R.; Narendran, V.; Manikandan, P.; Prabagaran, S.R. Identification of polybacterial communities in patients with postoperative, posttraumatic, and endogenous endophthalmitis through 16S rRNA gene libraries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mursalin, M.H.; Coburn, P.S.; Livingston, E.; Miller, F.C.; Astley, R.; Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Callegan, M.C. Bacillus S-layer-mediated innate interactions during endophthalmitis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, P.S.; Miller, F.C.; Enty, M.A.; Land, C.; LaGrow, A.L.; Mursalin, M.H.; Callegan, M.C. Expression of Bacillus cereus virulence-related genes in an ocular infection-related environment. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhende, M.; Karpe, A.; Arunachalam, S.; Therese, K.L.; Biswas, J. Endogenous endophthalmitis due to Roseomonas mucosa presenting as a subretinal abscess. J. Ophthalmic Inflamm. Infect. 2017, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brooke, J.S. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: An emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 2–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampo, M.; Ghazouani, O.; Cadiou, D.; Trichet, E.; Hoffart, L.; Drancourt, M. Dolosigranulum pigrum keratitis: A three-case series. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofa, D.; Gácser, A.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Candida parapsilosis, an emerging fungal pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Huang, C.; Guo, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, X. Conjunctival sac bacterial culture of patients using levofloxacin eye drops before cataract surgery: A real-world, retrospective study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022, 22, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, W.; Gearinger, L.S.; Usner, D.W.; DeCory, H.H.; Morris, T.W. Integrated analysis of three bacterial conjunctivitis trials of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%: Etiology of bacterial conjunctivitis and antibacterial susceptibility profile. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2011, 5, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badger-Emeka, L.I.; Emeka, P.M.; Aldossari, S.; Khalil, H.E. Terfezia claveryi and Terfezia boudieri extracts: An antimicrobial and molecular assay on clinical isolates associated with eye infections. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2020, 16, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchin, L. Individualised Inorganic Particles. Patent WO2015170060(A1), 2 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marchin, L. Use of Materials Incorporating Microparticles for Avoiding the Proliferation of Contaminants. Patent WO2015197992, 30 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, K.; Pecastaings, S.; LeGac, C.; Salvatico, S.; Feuillolay, C.; Guittard, M.; Marchin, L.; Verelst, M.; Roques, C. Demonstrating the In Vitro and In Situ Antimicrobial Activity of Oxide Mineral Microspheres: An Innovative Technology to Be Incorporated into Porous and Nonporous Materials. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuillolay, C.; Haddioui, L.; Verelst, M.; Furiga, A.; Marchin, L.; Roques, C. Antimicrobial activity of metal oxide microspheres: An innovative process for homogeneous incorporation into materials. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applerot, G.; Lipovsky, A.; Dror, R.; Perkas, N.; Nitzan, Y.; Lubart, R.; Gedanken, A. Enhanced antibacterial activity of nanocrystalline ZnO due to increased ROS-mediated cell injury. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.E., Jr.; Henrich, V.; Casey, W.; Clark, D.; Eggleston, C.; Andrew Felmy, A.F.; Maciel, G.; McCarthy, M.I.; Gratzel, M.; Goodman, D.W.; et al. Metal Oxide Surfaces and Their Interactions with Aqueous Solutions and Microbial Organisms. 1999. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub/197/ (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Pasquet, J.; Chevalier, Y.; Couval, E.; Bouvier, D.; Noizet, G.; Morlière, C.; Bolzinger, M.A. Antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide particles on five micro-organisms of the Challenge Tests related to their physicochemical properties. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 460, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquet, J.; Chevalier, Y.; Pelletier, J.; Couval, E.; Bouvier, D.; Bolzinger, M.A. The contribution of zinc ions to the antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 457, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ingudam, S.; Reed, S.; Gehring, A.; Strobaugh, T.P.; Irwin, P. Study on the mechanism of antibacterial action of magnesium oxide nanoparticles against foodborne pathogens. J. Nanobiotechnology 2016, 14, s12951–s13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Microbial Load (CFU) | Staphylococcus aureus | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Candida albicans |

|---|---|---|---|

| At C0/mL) | 5.2 × 105 | 1.7 × 105 | 2.4 × 103 |

| After C24 h in 0.9% NaCl (/mL) | 4.3 × 103 | 8.0 × 101 | 2.2 × 103 |

| After A24h contact with standard eye drop packaging (cap + tip) | >3.3 × 103 | >3.3 × 103 | 3.0 × 102 ± 0.4 × 102 CFU |

| After 24 h contact with Activated RispharmTM eye drop packaging (cap + tip) | 2.1 × 102 ± 7.0 × 101 | 3.2 × 102 ± 9.0 × 101 | 2.4 ×102 ± 6.0 × 101 |

| Log reduction Pylote TM vs. standard eye drop packaging | >1.2 | >1.1 | 0 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roquefeuil, L.; Iskandar, K.; Roques, C.; Marchin, L.; Guittard, M.; Poupet, H.; Brandely-Piat, M.-L.; Jobard, M. Evaluating and Managing the Microbial Contamination of Eye Drops: A Two-Phase Hospital-Based Study. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16070933

Roquefeuil L, Iskandar K, Roques C, Marchin L, Guittard M, Poupet H, Brandely-Piat M-L, Jobard M. Evaluating and Managing the Microbial Contamination of Eye Drops: A Two-Phase Hospital-Based Study. Pharmaceutics. 2024; 16(7):933. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16070933

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoquefeuil, Léa, Katia Iskandar, Christine Roques, Loïc Marchin, Mylène Guittard, Hélène Poupet, Marie-Laure Brandely-Piat, and Marion Jobard. 2024. "Evaluating and Managing the Microbial Contamination of Eye Drops: A Two-Phase Hospital-Based Study" Pharmaceutics 16, no. 7: 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16070933

APA StyleRoquefeuil, L., Iskandar, K., Roques, C., Marchin, L., Guittard, M., Poupet, H., Brandely-Piat, M.-L., & Jobard, M. (2024). Evaluating and Managing the Microbial Contamination of Eye Drops: A Two-Phase Hospital-Based Study. Pharmaceutics, 16(7), 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16070933