Abstract

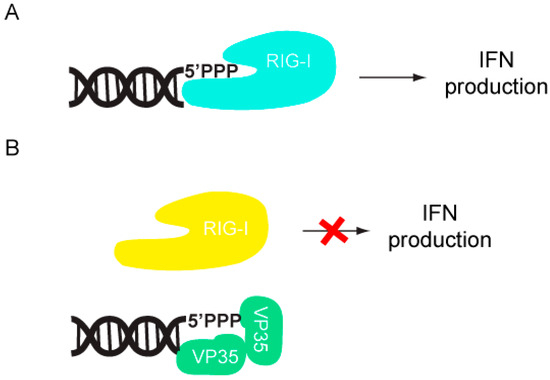

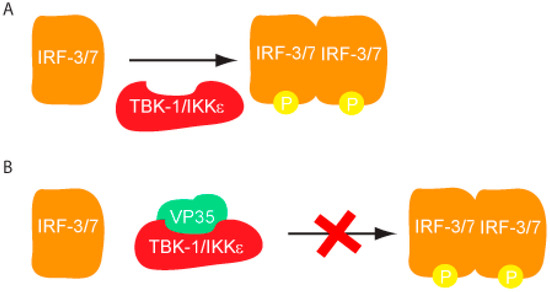

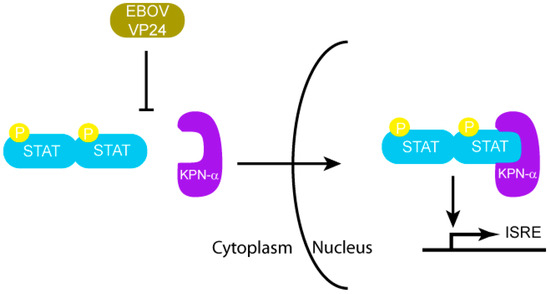

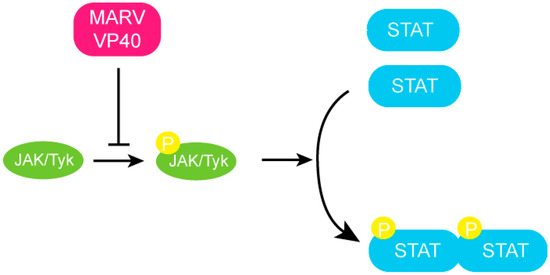

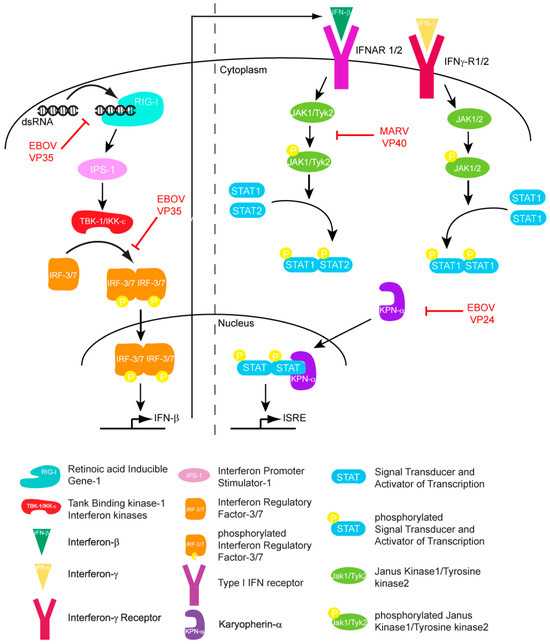

The Filoviridae family of viruses, which includes the genera Ebolavirus (EBOV) and Marburgvirus (MARV), causes severe and often times lethal hemorrhagic fever in humans. Filoviral infections are associated with ineffective innate antiviral responses as a result of virally encoded immune antagonists, which render the host incapable of mounting effective innate or adaptive immune responses. The Type I interferon (IFN) response is critical for establishing an antiviral state in the host cell and subsequent activation of the adaptive immune responses. Several filoviral encoded components target Type I IFN responses, and this innate immune suppression is important for viral replication and pathogenesis. For example, EBOV VP35 inhibits the phosphorylation of IRF-3/7 by the TBK-1/IKKε kinases in addition to sequestering viral RNA from detection by RIG-I like receptors. MARV VP40 inhibits STAT1/2 phosphorylation by inhibiting the JAK family kinases. EBOV VP24 inhibits nuclear translocation of activated STAT1 by karyopherin-α. The examples also represent distinct mechanisms utilized by filoviral proteins in order to counter immune responses, which results in limited IFN-α/β production and downstream signaling.

1. Filoviruses

Filoviruses are single-stranded, negative sense RNA viruses, which cause severe viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and non-human primates. Ebolaviruses (EBOV) and Marburgviruses (MARV) comprise the Filoviridae family. Five species of EBOV (Zaire, Sudan, Cote-d’Ivoire, Reston, Bundibugyo) and one species of MARV (Lake Victoria) have currently been identified. Among the five species of EBOV, Reston Ebolavirus (REBOV) does not cause disease in humans, although it is highly fatal to non-human primates [1,2]. Several patients tested seropositive for Cote-d’Ivoire species (CIEBOV), and displayed disease symptoms characteristic of hemorrhagic fever. However, no fatalities were directly attributed to CIEBOV. In contrast, REBOV was initially identified in an outbreak at an animal handling facility in Reston, Virginia, among macaques imported from the Philippines [2]. All of the macaques suffered from viral hemorrhagic fever resulting in death, while the two animal handlers who came in to contact with the animals had seroconverted. However, they did not display any disease symptoms. More recently, REBOV has been isolated from a swine population in the Philippines, whose animal handlers were seropositive, suggesting that the zoonotic nature of filoviruses may potentially make filoviruses a serious public health threat [2,3]. These isolated, but significant incidents highlight the potential threat of filoviruses worldwide. Currently limited information is known about the range of hosts that filoviruses infect and the virulence factors that promote zoonosis and lateral disease transfer (animal to animal). Studies to date, including some recent field studies indicate that several different species of fruit bats may serve as the natural reservoir for filoviruses [4,5,6]. The lethality of filoviral infections have been attributed to the ability of the virus to efficiently suppress the host innate antiviral responses early during infection, followed by impairment and/or dysregulation of the adaptive immune response and inflammatory pathways late during infection [7]. This is proposed to be due in large part to viral replication within dendritic cells, monocytes, macrophages, and hepatocytes [8]. Currently, the mechanisms involving host immune modulation by filoviral components are not clearly understood. In this review, we primarily focus on the following filoviral proteins: EBOV viral protein (VP) 35, EBOV VP24, and MARV VP40. Below we discuss current biochemical, structural and cell biological data and the mechanisms by which these filoviral proteins modulate the host innate immune responses. Having such information at hand will provide a starting point for developing countermeasures against filoviral infections.

2. Host Innate Immune Mechanisms

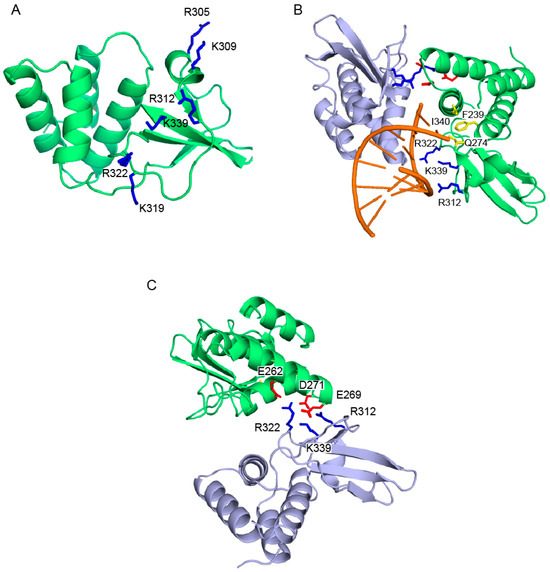

The host innate immune response is triggered upon recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which are located both on the surface and in the cytoplasm of cells. Although both Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and RIG-I like receptors (RLRs) play key roles in activating innate immune response, here we will primarily focus on RLRs as recent literature suggest that filoviruses antagonize innate immune responses downstream of RLRs. RLRs, which include retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation associated gene-5 (MDA5), are cytoplasmic sensors of viral infections. These receptors are likely regulated by autoinhibition, which prevents effector access to the N-terminal caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARDs) and helicase activity [9,10]. Upon activation, RLRs signal through the adaptor molecule IPS-1, which activates the kinases Tank binding kinase-1 (TBK-1) and I-Kappa-B kinase epsilon (IKKε). TBK-1/IKKε phosphorylate interferon regulatory factors (IRF) 3 and 7 [10]. Upon phosphorylation, IRF3/7 dimerize and localize to the nucleus, where they activate the transcription and production of interferon beta (IFN)-β (Figure 1). IFN-β can signal in both an autocrine and paracrine manner through interaction with its cognate receptor IFN alpha/beta receptor 1/2 (IFNAR1/2). Activation of IFNAR1/2 subsequently triggers the JAK/STAT signaling cascade, which involves the activation and autophosphorylation of Janus Kinase (JAK) family members JAK1 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), and the phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1 and 2 proteins. Upon phosphorylation, STAT1/2 dimerize and localize to the nucleus where they activate the transcription of the interferon stimulated genes (ISGs), such as double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR), 2’-5’ oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS), RNAseL, RNA-specific adenosine deaminsases (ADARs), and MHC class 1 and 2 [11]. The successful activation and transduction of these signaling events lead to upregulation of these and other host antiviral genes, thus establishing an antiviral state in the cell. Not surprisingly, these key innate immune signaling molecules are targeted by many virally encoded proteins, including those encoded by filoviruses. Both EBOV and MARV infections have been shown to modulate the expression of genes that are involved in the host immune response. Transcriptional profiling of human liver cells infected with ZEBOV or MARV show that there are major changes in the host gene expression profiles within 24 to 48 hours post infection [12,13]. Many of these genes are involved in immune regulation, coagulation, and apoptosis pathways. Furthermore, these gene expression changes are likely associated with severe suppression of ISG production, indicating that both ZEBOV and MARV are able to efficiently abrogate IFN responses and display rapid replication kinetics [12,13]. In contrast, REBOV infected cells displayed slower viral replication kinetics and also displayed significantly higher ISG production [13]. Together, these data suggests that REBOV is comparatively less efficient in abrogating host IFN responses in humans. These potential differences in host gene expression patterns may also contribute to observed differences in host tropism between REBOV and ZEBOV. However, many of these aspects have not been characterized at the molecular level.

Figure 1.

Filoviral proteins counter the host IFN response through multiple mechanisms in order to limit host antiviral responses.

4. Conclusions

Hemorrhagic fever outbreaks caused by filoviruses result in high fatality rates. The lack of approved therapeutics or vaccines along with the highly zoonotic nature of these viruses has made filoviruses a major health concern and a potential weapon of bioterrorism. In most filoviral infections, early innate immune responses are impaired, suggesting that virally encoded components are responsible for host immune evasion. Rapid progress in clinical research together with recent advances in biochemical and high resolution structural characterization of various filoviral proteins, as discussed above, are beginning to unravel some of the key host-viral interactions involved in this process. Ebola proteins VP35 and VP24 both impair innate immune responses. VP35 suppresses IFN production, while VP24 blocks nuclear translocation of phospho-STAT1, thereby preventing IFN mediated signaling. In contrast, MARV VP40, using a distinct mechanism, inhibits Jak and STAT phosphorylation, which also results in diminished host immunity during MARV infections. A more recent study suggests that other filoviral proteins, including EBOV VP30 and VP40, also counter the RNAi pathway [29]. While both EBOV and MARV retain similar genomic organization, variation in sequences has resulted in significant functional differences. Collectively, these studies highlight the complexity and diversity of immune evasion mechanisms used by filoviruses and point toward the need for detailed characterization of key host-viral interactions across different strains with varying host tropisms and pathogenesis. Future filoviral research aimed at combining the knowledge from regulatory mechanisms of host innate immunity with detailed characterization of viral components will likely provide critical knowledge that is needed for the development of prophylaxis and treatments against filoviruses.

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors’ laboratories are supported in part by NIH grants (1F32AI084324 to D.W.L., 5F32AI084453 to R.S.S., R01AI059536, R56AI089547 and AI057158 (Northeast Biodefense Center-Lipkin) to C.F.B. and R01AI081914 to G.K.A.); MRCE Developmental Grant (U54AI057160-Virgin (PI) to G.K.A.).

References and Notes

- Groseth, A.; Stroher, U.; Theriault, S.; Feldmann, H. Molecular characterization of an isolate from the 1989/90 epizootic of Ebola virus Reston among macaques imported into the United States. Virus Res. 2002, 87, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrling, P.B.; Geisbert, T.W.; Dalgard, D.W.; Johnson, E.D.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Hall, W.C.; Peters, C.J. Preliminary report: Isolation of Ebola virus from monkeys imported to USA. Lancet 1990, 335, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrette, R.W.; Metwally, S.A.; Rowland, J.M.; Xu, L.; Zaki, S.R.; Nichol, S.T.; Rollin, P.E.; Towner, J.S.; Shieh, W.J.; Batten, B.; et al. Discovery of swine as a host for the Reston ebolavirus. Science 2009, 325, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, E.M.; Kumulungui, B.; Pourrut, X.; Rouquet, P.; Hassanin, A.; Yaba, P.; Delicat, A.; Paweska, J.T.; Gonzalez, J.P.; Swanepoel, R. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 2005, 438, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towner, J.S.; Pourrut, X.; Albarino, C.G.; Nkogue, C.N.; Bird, B.H.; Grard, G.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Gonzalez, J.P.; Nichol, S.T.; Leroy, E.M. Marburg virus infection detected in a common African bat. PLoS One 2007, 2, e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, J.S.; Amman, B.R.; Sealy, T.K.; Carroll, S.A.; Comer, J.A.; Kemp, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Paddock, C.D.; Balinandi, S.; Khristova, M.L.; et al. Isolation of genetically diverse Marburg viruses from Egyptian fruit bats. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M. The role of the Type I interferon response in the resistance of mice to filovirus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T.W. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet 2011, 377, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 227, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, M.; Fujita, T. RNA recognition and signal transduction by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 227, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katze, M.G.; He, Y.; Gale, M., Jr. Viruses and interferon: A fight for supremacy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, A.L.; Ling, L.; Nichol, S.T.; Hibberd, M.L. Whole-genome expression profiling reveals that inhibition of host innate immune response pathways by Ebola virus can be reversed by a single amino acid change in the VP35 protein. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5348–5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kash, J.C.; Muhlberger, E.; Carter, V.; Grosch, M.; Perwitasari, O.; Proll, S.C.; Thomas, M.J.; Weber, F.; Klenk, H.D.; Katze, M.G. Global suppression of the host antiviral response by Ebola- and Marburgviruses: Increased antagonism of the type I interferon response is associated with enhanced virulence. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 3009–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehedi, M.; Falzarano, D.; Seebach, J.; Hu, X.; Carpenter, M.S.; Schnittler, H.J.; Feldmann, H. A new ebola virus nonstructural glycoprotein expressed through RNA editing. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 5406–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, C.F.; Mikulasova, A.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Paragas, J.; Muhlberger, E.; Bray, M.; Klenk, H.D.; Palese, P.; Garcia-Sastre, A. The Ebola virus VP35 protein inhibits activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 7945–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, C.F.; Wang, X.; Muhlberger, E.; Volchkov, V.; Paragas, J.; Klenk, H.D.; Garcia-Sastre, A.; Palese, P. The Ebola virus VP35 protein functions as a type I IFN antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 12289–12294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, W.B.; Loo, Y.M.; Gale, M., Jr.; Hartman, A.L.; Kimberlin, C.R.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Saphire, E.O.; Basler, C.F. Ebola virus VP35 protein binds double-stranded RNA and inhibits alpha/beta interferon production induced by RIG-I signaling. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5168–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, A.L.; Towner, J.S.; Nichol, S.T. A C-terminal basic amino acid motif of Zaire ebolavirus VP35 is essential for type I interferon antagonism and displays high identity with the RNA-binding domain of another interferon antagonist, the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. Virology 2004, 328, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, A.L.; Dover, J.E.; Towner, J.S.; Nichol, S.T. Reverse genetic generation of recombinant Zaire Ebola viruses containing disrupted IRF-3 inhibitory domains results in attenuated virus growth in vitro and higher levels of IRF-3 activation without inhibiting viral transcription or replication. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 6430–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.W.; Ginder, N.D.; Fulton, D.B.; Nix, J.; Basler, C.F.; Honzatko, R.B.; Amarasinghe, G.K. Structure of the Ebola VP35 interferon inhibitory domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.W.; Prins, K.C.; Borek, D.M.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Tufariello, J.M.; Ramanan, P.; Nix, J.C.; Helgeson, L.A.; Otwinowski, Z.; Honzatko, R.B.; et al. Structural basis for dsRNA recognition and interferon antagonism by Ebola VP35. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, K.C.; Delpeut, S.; Leung, D.W.; Reynard, O.; Volchkova, V.A.; Reid, S.P.; Ramanan, P.; Cardenas, W.B.; Amarasinghe, G.K.; Volchkov, V.E.; et al. Mutations abrogating VP35 interaction with double-stranded RNA render Ebola virus avirulent in guinea pigs. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3004–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.P.; Cardenas, W.B.; Basler, C.F. Homo-oligomerization facilitates the interferon-antagonist activity of the ebolavirus VP35 protein. Virology 2005, 341, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, K.C.; Cardenas, W.B.; Basler, C.F. Ebola virus protein VP35 impairs the function of interferon regulatory factor-activating kinases IKKepsilon and TBK-1. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 3069–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.H.; Kubota, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Jones, S.; Bradfute, S.B.; Bray, M.; Ozato, K. Ebola Zaire virus blocks type I interferon production by exploiting the host SUMO modification machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Cerveny, M.; Yan, Z.; He, B. The VP35 protein of Ebola virus inhibits the antiviral effect mediated by double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, M.; Gantke, T.; Muhlberger, E. Ebola virus VP35 antagonizes PKR activity through its C-terminal interferon inhibitory domain. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 8993–8997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haasnoot, J.; de Vries, W.; Geutjes, E.J.; Prins, M.; de Haan, P.; Berkhout, B. The Ebola virus VP35 protein is a suppressor of RNA silencing. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabozzi, G.; Nabel, C.S.; Dolan, M.A.; Sullivan, N.J. Ebolavirus proteins suppress the effects of small interfering RNA by direct interaction with the mammalian RNA interference pathway. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 2512–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, C.R.; Bornholdt, Z.A.; Li, S.; Woods, V.L., Jr.; MacRae, I.J.; Saphire, E.O. Ebolavirus VP35 uses a bimodal strategy to bind dsRNA for innate immune suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.W.; Shabman, R.S.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Prins, K.C.; Borek, D.M.; Wang, T.; Muhlberger, E.; Basler, C.F.; Amarasinghe, G.K. Structural and Functional Characterization of Reston Ebola Virus VP35 Interferon Inhibitory Domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 399, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.P.; Valmas, C.; Martinez, O.; Sanchez, F.M.; Basler, C.F. Ebola virus VP24 proteins inhibit the interaction of NPI-1 subfamily karyopherin alpha proteins with activated STAT1. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 13469–13477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, L.H.; Kiley, M.P.; McCormick, J.B. Descriptive analysis of Ebola virus proteins. Virology 1985, 147, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, J.M.; Johnson, R.F.; Han, Z.; Harty, R.N. Contribution of ebola virus glycoprotein, nucleoprotein, and VP24 to budding of VP40 virus-like particles. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 7344–7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoenen, T.; Groseth, A.; Kolesnikova, L.; Theriault, S.; Ebihara, H.; Hartlieb, B.; Bamberg, S.; Feldmann, H.; Stroher, U.; Becker, S. Infection of naive target cells with virus-like particles: implications for the function of ebola virus VP24. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7260–7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenen, T.; Jung, S.; Herwig, A.; Groseth, A.; Becker, S. Both matrix proteins of Ebola virus contribute to the regulation of viral genome replication and transcription. Virology 2010, 403, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, L.; Sun, Y.; Nabel, G.J. The assembly of Ebola virus nucleocapsid requires virion-associated proteins 35 and 24 and posttranslational modification of nucleoprotein. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, T.; Halfmann, P.; Sagara, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Regions in Ebola virus VP24 that are important for nucleocapsid formation. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, S247–S250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Noda, T.; Halfmann, P.; Jasenosky, L.; Kawaoka, Y. Ebola virus (EBOV) VP24 inhibits transcription and replication of the EBOV genome. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, S284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.; Davis, K.; Geisbert, T.; Schmaljohn, C.; Huggins, J. A mouse model for evaluation of prophylaxis and therapy of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 179, S248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebihara, H.; Takada, A.; Kobasa, D.; Jones, S.; Neumann, G.; Theriault, S.; Bray, M.; Feldmann, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Molecular determinants of Ebola virus virulence in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volchkov, V.E.; Chepurnov, A.A.; Volchkova, V.A.; Ternovoj, V.A.; Klenk, H.D. Molecular characterization of guinea pig-adapted variants of Ebola virus. Virology 2000, 277, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, M.; Reid, S.P.; Leung, L.W.; Basler, C.F.; Volchkov, V.E. Ebolavirus VP24 binding to karyopherins is required for inhibition of interferon signaling. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.P.; Leung, L.W.; Hartman, A.L.; Martinez, O.; Shaw, M.L.; Carbonnelle, C.; Volchkov, V.E.; Nichol, S.T.; Basler, C.F. Ebola virus VP24 binds karyopherin alpha1 and blocks STAT1 nuclear accumulation. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5156–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cros, J.F.; Garcia-Sastre, A.; Palese, P. An unconventional NLS is critical for the nuclear import of the influenza A virus nucleoprotein and ribonucleoprotein. Traffic 2005, 6, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neill, R.E.; Palese, P. NPI-1, the human homolog of SRP-1, interacts with influenza virus nucleoprotein. Virology 1995, 206, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, M.R.; Teh, T.; Jans, D.; Brinkworth, R.I.; Kobe, B. Structural basis for the specificity of bipartite nuclear localization sequence binding by importin-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27981–27987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Lebeda, F.J.; Olson, M.A. Fold prediction of VP24 protein of Ebola and Marburg viruses using de novo fragment assembly. J. Struct. Biol. 2009, 167, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enterlein, S.; Schmidt, K.M.; Schumann, M.; Conrad, D.; Krahling, V.; Olejnik, J.; Muhlberger, E. The marburg virus 3' noncoding region structurally and functionally differs from that of ebola virus. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 4508–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmas, C.; Grosch, M.N.; Schumann, M.; Olejnik, J.; Martinez, O.; Best, S.M.; Krahling, V.; Basler, C.F.; Muhlberger, E. Marburg virus evades interferon responses by a mechanism distinct from ebola virus. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessen, A.; Volchkov, V.; Dolnik, O.; Klenk, H.D.; Weissenhorn, W. Crystal structure of the matrix protein VP40 from Ebola virus. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4228–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomis-Ruth, F.X.; Dessen, A.; Timmins, J.; Bracher, A.; Kolesnikowa, L.; Becker, S.; Klenk, H.D.; Weissenhorn, W. The matrix protein VP40 from Ebola virus octamerizes into pore-like structures with specific RNA binding properties. Structure 2003, 11, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruigrok, R.W.; Schoehn, G.; Dessen, A.; Forest, E.; Volchkov, V.; Dolnik, O.; Klenk, H.D.; Weissenhorn, W. Structural characterization and membrane binding properties of the matrix protein VP40 of Ebola virus. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 300, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2011 by the authors. License MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).