Abstract

The emergence of pandemic H1N1 influenza viruses in April 2009 and the continuous evolution of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses underscore the urgency of novel approaches to chemotherapy for human influenza infection. Anti-influenza drugs are currently limited to the neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir and zanamivir) and to M2 ion channel blockers (amantadine and rimantadine), although resistance to the latter class develops rapidly. Potential targets for the development of new anti-influenza agents include the viral polymerase (and endonuclease), the hemagglutinin, and the non-structural protein NS1. The limitations of monotherapy and the emergence of drug-resistant variants make combination chemotherapy the logical therapeutic option. Here we review the experimental data on combination chemotherapy with currently available agents and the development of new agents and therapy targets.

1. Introduction

Influenza continues to cause an unacceptable number of deaths and substantial economic losses worldwide. Although vaccination strategies are the mainstay of influenza control and prevention, the efficacy of this approach can be limited by the four-to-six-month minimum time required to produce a specific vaccine against a newly emergent virus, a poor match between the vaccine and the circulating strain, and poor immune responses among elderly patients [1]. Influenza virus infection can be effectively treated with anti-influenza antiviral agents [2,3], as it was during the rapid emergence of the pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in 2009 when no vaccine was available. At present, two classes of antiviral drugs are approved for influenza therapy: M2 ion channel blockers (oral amantadine and its derivative rimantadine) and neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors (oral oseltamivir and inhaled zanamivir). These agents either prevent viral uncoating inside the cell (M2-blockers) or prevent the release of progeny virions from infected cells (NA inhibitors). The development of resistance is a major obstacle to the usefulness of both classes of anti-influenza agents, which could provide a growth advantage to variants carrying drug-resistance mutations, more likely under drug selective pressure. The emergence of pathogenic, transmissible, amantadine-resistant H1N1 and H3N2 seasonal influenza variants, amantadine resistance in the pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza viruses, and a significant increase in amantadine resistance among some highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses, have limited the usefulness of M2 ion channel blockers [4,5,6,7]. The NA inhibitor resistance-associated mutations in influenza viruses are drug-specific and NA subtype-specific [8]. In experimental animal models, it was shown that the NA inhibitor resistant variants differed in fitness and transmissibility; this difference may be influenced by the location of NA mutation(s) [9,10,11]. These findings indicated that transmissible NA inhibitor resistant variants may emerge, and therefore continuous monitoring for NA inhibitor resistance is necessary. Until 2007, influenza viruses resistant to the NA inhibitor oseltamivir were isolated at a low level. The incidence of oseltamivir resistance seen in clinical trial samples was 0.33% (4/1228) in adults/adolescents (≥13 years), 4.0% (17/421) in children (1 ≤ 12 years) and 1.26% overall [12]. However, during the 2007-2008 influenza season, oseltamivir-resistant variants with the H275Y NA amino acid substitution (N1 numbering) became widespread, first in the Northern Hemisphere [13,14] and then in the Southern Hemisphere [15]. Importantly, oseltamivir-resistant variants have rarely been reported among the novel pandemic H1N1 influenza viruses that emerged in April 2009 [16], and oseltamivir is the treatment agent favored by clinicians [17,18].

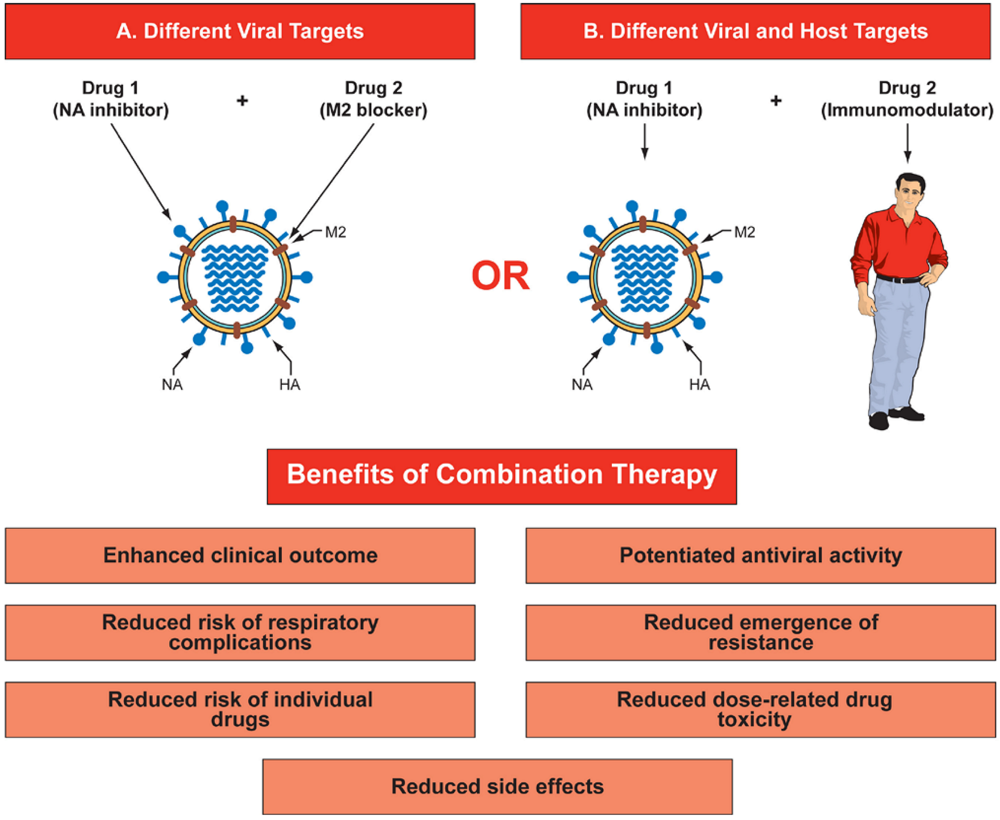

An attractive approach for countering drug resistance is combination chemotherapy with two or more drugs that target different viral proteins or host factors and for which the mechanisms of resistance differ. Such combination therapy may reduce the likelihood that resistance to a single drug will emerge and reduces the effect of resistance that does emerge. Moreover, combination therapy may not only potentiate antiviral activity but may also enhance clinical outcomes by allowing reductions of the doses of individual drugs, thereby reducing dose-related drug toxicity and side effects. In addition, it can reduce the risk of respiratory complications (Figure 1).

The pharmacological rationale for multiple-drug combination therapy is exemplified by combination HIV treatment regimens that keep the plasma viral load below detectable levels, prevent the emergence of resistance, and allow successful management of HIV-infected patients [19,20]. This review presents the experimental and available clinical data on combination chemotherapy for influenza and discusses several investigational and exploratory agents that may be used in combination.

Figure 1.

Benefits of combination therapy for influenza. Combination therapy could target different viral proteins (A) that have different mechanisms of antiviral action (for example, NA inhibitor and M2 ion channel blocker), or (B) target virus and host factors that affect virus replication and host defense mechanisms (for example, NA inhibitor and immunomodulator). This diagram represents only double drug combinations, but a multidrug approach could consist of three or more drugs in combination. Abbreviations: HA- hemagglutinin; NA - neuraminidase; M2 - matrix protein.

4. Clinical data

Preclinical studies have demonstrated the benefits of combination therapy over monotherapy in inhibiting virus replication and reducing the risk of the emergence of resistant viruses. However, the clinical evaluation of combination therapy with currently available agents has received little attention. Controlled clinical therapy trials are impeded not only by the difficulty of organizing them but also by the limited number of antiviral drugs available for use in combinations and the high level of resistance to the adamantanes (amantadine and rimantadine) in circulating influenza strains. Several years ago, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Antiviral Study Group compared outcomes among hospitalized adults with influenza who received either nebulized zanamivir plus oral rimantadine or nebulized saline placebo plus oral rimantadine [51]. These studies were undertaken before the spread of amantadine resistance worldwide. Patients treated with zanamivir plus rimantadine demonstrated a nonsignificant trend toward fewer days of virus shedding and were less likely to have a severe cough. Moreover, no resistant variants were found in the group receiving combination therapy, while 2 of 11 patients in the rimantadine monotherapy group had resistant virus [51].

To detect unanticipated interactions of the drugs used in combinations, the pharmacokinetics of amantadine (100 mg orally twice daily) and oseltamivir (75 mg orally twice daily) administered alone and in combination for five days was evaluated in a randomized, crossover study (n = 17) [52]. The pharmacokinetics of amantadine was not affected by coadministration of oseltamivir. Similarly, amantadine did not affect the pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir or its metabolite, oseltamivir carboxylate. There was no evidence of an increase in the frequency or severity of adverse events when amantadine and oseltamivir were used in combination [52].

The pharmacokinetics and tolerability of the oseltamivir-probenecid combination were evaluated in healthy volunteers [53,54]. The two tested regimens were (1) oseltamivir 150 mg once a day and probenecid 500 mg orally four times a day for four days [53] and (2) 75 mg of oral oseltamivir every 48 h and 500 mg of probenecid four times daily for 15 days [54]. Subjects who received both oseltamivir and probenecid had an oseltamivir carboxylate plasma concentration 2-2.5 times that of subjects who received oseltamivir alone. Probenecid inhibits renal tubular urate resorption and reduces the excretion of several medications [55,56]. Therefore, the oseltamivir-probenecid combination must be used with caution in patients receiving renally excreted medications.

Ongoing NIAID efforts to conduct clinical studies of combination anti-influenza regimens will provide much-needed information on the prospects of this approach for the treatment of influenza.

6. Conclusions

The currently available influenza antivirals have a number of limitations; therefore, more effective antiviral strategies are needed. The possibilities include parenteral NA inhibitors, development of novel antiviral drugs (polymerase and endonuclease inhibitors, sialidases, long-acting NA inhibitors, hemagglutinin inhibitors, and non-structural protein NS1 inhibitors), and immunotherapy. Combination therapy with two or more drugs is a promising approach for control of seasonal influenza and of severe infection with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses. Drug combination studies in vitro and in vivo have shown the potential for synergistic or additive antiviral activity and for inhibiting the development of resistance; these qualities must now be demonstrated in clinical trials. All of the available information supports the initiation of clinical trials on combination chemotherapy for influenza. The planning of such studies is ongoing, and consideration is being given to clinical and virologic evaluations with determination of influenza virus loads in the patient, the molecular and biological characterization of viruses for resistance and fitness, and the detailed collection of pharmacokinetic data to evaluate safety and toxicity. Future considerations for combination therapy are dual NA inhibitors, triple combinations, and inclusion of novel agents. The new strategies directed at unexplored targets, such as drugs that affect host antiviral responses, should be also developed.

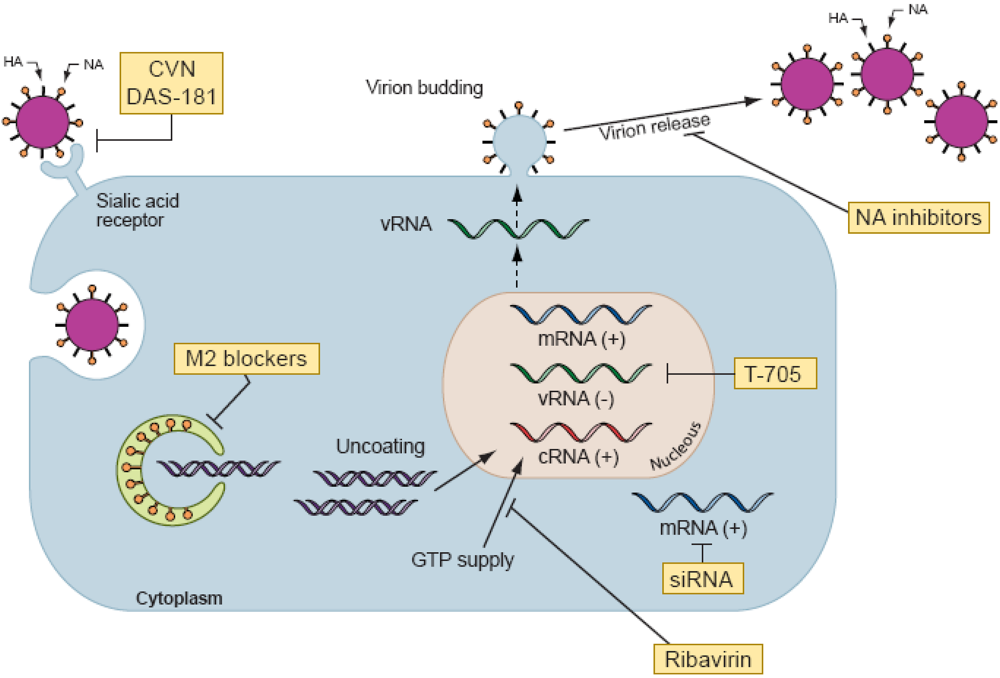

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of influenza virus replication cycle and sites of action of antiviral agents. Note. Influenza A virus contains eight RNA segments of negative polarity coding for at least 11 viral proteins. The surface proteins of influenza A virus consist of two glycoproteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), and the M2 protein. The HA protein attaches the virus to sialic acid–containing receptors on the cell surface and initiates infection. A fusion protein inhibitor (DAS-181) targets the influenza virus receptor in the host respiratory tract and inhibits virus attachment. Cyanovirin-N (CVN) binds to high-mannose oligosaccharides on HA and inhibits the entry of virus into cells. For most influenza A viruses, the M2 ion channel blockers (amantadine and rimantadine) impede viral replication at an early stage of infection after penetration of the cell but prior to uncoating. M2 blockers inhibit the decrease in pH within the virion and thus block the release of viral RNA into the cytoplasm and prevent transportation of the viral genome to the nucleus. Inhibition of the viral polymerase, an essential component of viral RNA replication in the nucleus, can be blocked by the polymerase inhibitors ribavirin and T-705. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that target different viral genes can inhibit viral replication. Several mechanisms of action have been proposed for the anti-influenza virus activity of ribavirin. One is the inhibition of the cellular enzyme inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, resulting in a decrease in the intracellular guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP) that is required for nucleic acid synthesis. Ribavirin triphosphate also inhibits the function of virus-coded RNA polymerases which are necessary to initiate and elongate viral mRNAs. Late in infection, NA cleaves sialic acid–containing receptors and facilitates the release of budding virions. NA inhibitors (zanamivir, oseltamivir, peramivir, and LANI) block NA activity, preventing the release of virions from the cell.

Conflict of Interest

E.G. and R.W. report receiving research funding from F. Hoffmann–La Roche and BioCryst Pharmaceuticals. R.W. reports receiving consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN266200700005C; and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). We thank Klo Spelshouse for illustrations and gratefully acknowledge the editorial assistance of Sharon Naron.

References

- Stephenson, I.; Nicholson, K.G. Influenza: vaccination and treatment. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 17, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, A.K.; Hayden, F.G.; John, F. Enders lecture 2006: Antivirals for influenza . J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscona, A. Medical management of influenza infection. Annu. Rev. Med. 2008, 59, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, R.A.; Medina, M.J.; Xu, X.; Perez-Oronoz, G.; Wallis, T.R.; Davis, X.M.; Povinelli, L.; Cox, N.J.; Klimov, A.I. Incidence of amantadine resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses isolated worldwide from 1994 to 2005: a cause of concern. Lancet 2005, 366, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deyde, V.M.; Xu, X.; Bright, R.A.; Shaw, M.; Smith, C.B.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, Y.; Gubareva, L.V.; Cox, N.J.; Klimov, A.I. Surveillance of resistance to adamantanes among influenza A (H3N2) and A (H1N1) viruses isolated worldwide. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurt, A.C.; Selleck, P.; Komadina, N.; Shaw, R.; Brown, L.; Barr, I.G. Susceptibility of highly pathogenic A (H5N1) avian influenza viruses to the neuraminidase inhibitors and adamantanes. Antiviral Res. 2007, 73, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubareva, L.; Okomo-Adhiambo, M.; Deyde, V.; Fry, A.M.; Sheu, T.G.; Garten, R.; Smith, D.C.; Barnes, J.; Myrick, A.; Hillman, M.; Shaw, M.; Bridges, C.; Klimov, A.; Cox, N. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: Drug susceptibility of swine origin influenza A (H1N1) viruses, April 2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2009, 58, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferraris, O.; Lina, B. Mutations of neuraminidase implicated in neuraminidase inhibitors resistance. J. Clin. Virol. 2008, 41, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herlocher, M.L.; Carr, J.; Ives, J.; Elias, S.; Truscon, R.; Roberts, N.; Monto, A.S. Influenza virus carrying an R292K mutation in the neuraminidase gene is not transmitted in ferrets. Antiviral Res. 2002, 54, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, H-L; Herlocher, L.M.; Hoffmann, E.; Matrosovich, M.N.; Monto, A.S.; Webster, R.G.; Govorkova, E.A. Neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant influenza viruses may differ substantially in fitness and transmissibility . Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 4075–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvier, N.M.; Lowen, A.C.; Palese, P. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza A viruses are transmitted efficiently among guinea pigs by direct contact but not by aerosol. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10052–10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, P.; Small, I.; Smith, J.; Suter, P.; Dutkowski, R. Oseltamivir (TamifluR) and its potential for use in the event of an influenza pandemic. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 55, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackenby, A.; Hungnes, O.; Dudman, S.G.; Meijer, A.; Paget, W.J.; Hay, A. J.; Zambon, M.C. Emergence of resistance to oseltamivir among influenza A (H1N1) viruses in Europe. Eurosurveillance 2008, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Dharan, N.J.; Gubareva, L.V.; Meyer, J.J.; Okomo-Adhiambo, M.; McClinton, R.C.; Marshall, S.A.; George, K. St.; Epperson, S.; Brammer, L.; Klimov, A.I.; Bresee, J.S.; Fry, A.M. For the Oseltamivir-Resistance Working Group. Infections with oseltamivir-resistant influenza A (H1N1) virus in the United States. JAMA 2009, 301, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurt, A.C.; Ernest, J.; Deng, Y-M.; Iannello, P.; Besselaar, T.G.; Birch, C.; Buchy, P.; Chittaganpitch, M.; Chiu, S-C.; Dwyer, D.; Guigoni, A.; Harrower, B.; Kei, I.P.; Kok, T.; Lin, C.; McPhie, K.; Mohd, A.; Olveda, R.; Panayotou, T.; Rawlinson, W.; Scott, L.; Smith, D.; D’Souza, H.; Komadina, N.; Shaw, R.; Kelso, A.; Barr, I.G. Emergence and spread of oseltamivir-resistant A (H1N1) influenza viruses in Oceania, South East Asia and South Africa . Antiviral Res. 2009, 83, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, E.; Chotpitayasunondh, T.; Gao, Z.; Harper, S.A.; Shaw, M.; Uyeki, T.M.; Zaki, S.R.; Hayden, F.G.; Hui, D.S.; Kettner, J.D.; Kumar, A.; Lim, M.; Shindo, N.; Penn, C.; Nicholson, K.G. Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on the Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1708–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, I.W.; Hung, I.F.; To, K.K.; Chan, K.H.; Wong, S.S.; Chan, J.F.; Cheng, V.C.; Tsang, O.T.; Lai, S.T.; Lau, Y.L.; Yuen, K.Y. The natural viral load profile of patients with pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) and the effect of oseltamivir treatment. Chest 2010, 137, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, L.M.; Chow, A.L.; Lye, D.C.; Tan, A.S.; Krishnan, P.; Cui, L.; Win, N.N.; Chan, M.; Lim, P.L.; Lee, C.C.; Leo, Y.S. Effects of early oseltamivir therapy on viral shedding in 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulick, R. Combination therapy for patients with HIV-1 infection: the use of dual nucleoside analogues with protease inhibitors and other agents . AIDS 1998, 12, S17–S22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raboud, J.M.; Harris, M.; Rae, S.; Montaner, J.S. Impact of adherence on duration of virological suppression among patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2002, 3, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhnel, J. Evaluation of synergism or antagonism for the combined action of antiviral agents. Antiviral Res. 1990, 13, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galegov, G.A.; Pushkarskaya, N.L.; Obrosova-Serova, N.P.; Zhdanov, V.M. Combined action of ribavirin and rimantadine in experimental myxovirus infection. Experientia 1977, 33, 905–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Clercq, E. Antiviral agents active against influenza A viruses. Nature Rev. 2006, 5, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidwell, R.W.; Bailey, K.W.; Wong, M.H.; Barnard, D.L.; Smee, D.F. In vitro and in vivo influenza virus-inhibitory effects of viramidine. Antiviral Res. 2005, 68, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smee, D.F.; Wong, M.H.; Bailey, K.W.; Sidwell, R.W. Activities of oseltamivir and ribavirin used alone and in combination against infections in mice with recent isolates of influenza A (H1N1) and B viruses. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 2006, 17, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, F.G.; Douglas Jr., R.G.; Simons, R. Enhancement of activity against influenza viruses by combinations of antiviral agents . Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1980, 18, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayden, F.G.; Slepushkin, A.N.; Pushkarskaya, N.L. Combined interferon-α2, rimantadine hydrochloride, and ribavirin inhibition of influenza virus replication in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1984, 25, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shigeta, S.; Mori, S.; Watanabe, J.; Soeda, S.; Takahashi, K.; Yamase, T. Synergistic anti-influenza virus A (H1N1) activities of PM-523 (polyoxometalate) and ribavirin in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 1423–1427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Serkedjieva, J. Combined antiinfluenza virus activity of Flos verbasci infusion and amantadine derivatives . Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gegova, G.; Manolova, N.; Serkedzhieva, Iu.; Maksimova, V.; Uzunov, S.; Dzeguze, D.; Indulen, M. Combined effect of selected antiviral substances of natural and synthetic origin. II. Anti-influenza activity of a combination of a polyphenolic complex isolated from Geranium sanguineum L. and rimantadine in vivo. Acta Microbiol Bulg. 1993, 30, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.U.; Lew, W.; Williams, M.A.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Swaminathan, S.; Bischofberger, N.; Chen, M.S.; Mendel, D.B.; Tai, C.Y.; Laver, W.G.; Stevens, R.C. Influenza neuraminidase inhibitors possessing a novel hydrophobic interactions in the enzyme active site: design, synthesis, and structural analysis of carbocyclic sialic acid analogues with potent anti-influenza activity . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Itzstein, M.; Wu, W.-Y.; Kok, G.K.; Pegg, M.S.; Dyason, J.C.; Jin, B.; Van Phan, T.; Smithe, M.L.; White, H.F.; Oliver, S.W.; Colman, P.M.; Varghese, J.N.; Ryan, D.M.; Woods, J.M.; Bethell, R.C.; Hotham, V.J.; Cameron, J.M.; Penn, C.R. Rational design of potent sialidase-based inhibitors of influenza virus replication. Nature 1993, 363, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, Y.S.; Chand, P.; Bantia, S.; Kotian, P.L.; Dehghani, A.; El-Kattan, Y.; Lin, T.; Hutchison, T.L.; Elliot, A.J.; Parker, C.D.; Ananth, S.L.; Horn, L.L.; Laver, G.W.; Montgomery, J.A. BCX-1812 (RWJ-270201): discovery of a novel, highly potent, orally active and selective influenza neuraminidase inhibitor through structure-based drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3482–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madren, L.K.; Shipman Jr., C.; Hayden, F.G. In vitro inhibitory effects of combinations of anti-influenza agents . Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1995, 6, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Smee, D.F.; Bailey, K.W.; Morrison, A.C.; Sidwell, R.W. Combination treatment of influenza A virus infections in cell culture and in mice with the cyclopentane neuraminidase inhibitor RWJ-270201 and ribavirin. Chemotherapy 2002, 48, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govorkova, E.A.; Fang, H.B.; Tan, M.; Webster, R.G. Neuraminidase inhibitor-rimantadine combinations exert additive and synergistic anti-influenza virus effects in MDCK cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 4855–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyushina, N.A.; Bovin, N.V.; Webster, R.G.; Govorkova, E.A. Combination chemotherapy, a potential strategy for reducing the emergence of drug-resistant influenza A variants. Antiviral Res. 2006, 70, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smee, D.F.; Hurst, B.L.; Wong, M.H.; Bailey, K.W.; Morrey, J.D. Effects of double combinations of amantadine, oseltamivir, and ribavirin on influenza A (H5N1) virus infections in cell culture and in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2120–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.T.; Hoopes, J.D.; Le, M.H.; Smee, D.F.; Patick, A.K.; Faix, D.J.; Blair, P.J.; de Jong, M.D.; Prichard, M.N.; Went, G.T. Triple combination of amantadine, ribavirin, and oseltamivir is highly active and synergistic against drug resistant influenza virus strains in vitro. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.T.; Hoopes, J.D.; Smee, D.F.; Prichard, M.N.; Driebe, E.M.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Le, M.H.; Keim, P.S.; Spence, R.P.; Went, G.T. Triple combination of oseltamivir, amantadine, and ribavirin displays synergistic activity against multiple influenza virus strains in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 4115–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, M.N.; Shipman Jr., C. A three-dimensional model to analyze drug-drug interactions . Antiviral Res. 1990, 14, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galabov, A.S.; Simeonova, L.; Gegova, G. Rimantadine and oseltamivir demonstrate synergistic combination effect in an experimental infection with type A (H3N2) influenza virus in mice . Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2006, 17, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ilyushina, N.A.; Hoffmann, E.; Salomon, R.; Webster, R.G.; Govorkova, E.A. Amantadine-oseltamivir combination therapy for H5N1 influenza virus infection in mice. Antiviral Ther. 2007, 12, 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyushina, N.A.; Hay, A.; Yilmaz, N.; Boon, A.C.M.; Webster, R.G.; Govorkova, E.A. Oseltamivir-ribavirin combination therapy for highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus infection in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3889–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masihi, K.N.; Schweiger, B.; Finsterbusch, T.; Hengel, H. Low dose oral combination chemoprophylaxis with oseltamivir and amantadine for influenza A virus infection in mice. J. Chemother. 2007, 19, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.Z.; Knight, V.; Wyde, P.R.; Drake, S.; Couch, R.B. Amantadine and ribavirin aerosol treatment of influenza A and B infection in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1980, 17, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayden, F.G. Combinations of antiviral agents for treatment of influenza virus infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1986, 18, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhirnov, O.P. High protection of animals lethally infected with influenza virus by aprotinin-rimantadine combinations. J. Med. Virol. 1987, 21, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, J.S.M.; de Jong, M.D.; Guan, Y. Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clin. Mircob. Rev. 2007, 20, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leneva, I.A.; Roberts, N.; Govorkova, E.A.; Goloubeva, O.G.; Webster, R.G. The neuraminidase inhibitor GS 4101 (oseltamivir phosphate) is efficacious against A/Hong Kong/156/97 (H5N1) and A/Hong Kong/1074/99 (H9N2) influenza viruses. Antiviral Res. 2000, 48, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ison, M.G.; Gnann Jr., J.W.; Nagy-Agren, S.; Treannor, J.; Paya, C.; Steigbigel, R.; Elliott, M.; Weiss, H.L.; Hayden, F.G. Safety and efficacy of nebulized zanamivir in hospitalized patients with serious influenza . Antiviral Ther. 2003, 8, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, D.; Roy, S.; Rayner, C.; Amer, A.; Howard, D.; Smith, J.R.; Evans, T.G. A randomized, crossover study to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of amantadine and oseltamivir administered alone and in combination . PLoS One 2007, 2, e1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, G.; Cihlar, T.; Oo, C.; Ho, E.S.; Prior, K.; Wiltshire, H.; Barrett, J.; Liu, B.; Ward, P. The anti-influenza drug oseltamivir exhibits low potential to induce pharmacokinetic drug interactions via renal secretion-correlation of in vivo and in vitro studies. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002, 30, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holodniy, M.; Penzak, S.R.; Straight, T.M.; Davey, R.T.; Lee, K.K.; Goetz, M.B.; Raisch, D.W.; Cunningham, F.; Lin, E.T.; Olivo, N.; Deyton, L.R. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of oseltamivir combined with probenecid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3013–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bony, F.; Tod, M.; Bidault, R.; On, N.T.; Posner, J.; Rolan, P. Multiple interactions of cimetidine and probenecid with valaciclovir and its metabolite acyclovir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, J.S.; Devane, C.L.; Liston, H.L.; Boulton, D.W.; Risch, S.C. The effects of probenecid on the disposition of risperidone and olanzapine in healthy volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 71, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Kuno, M.; Kamiyama, T.; Kozaki, K.; Nomura, N.; Egawa, H.; Minami, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Narita, H.; Shiraki, K. In vitro and in vivo activities of anti-influenza virus compound T-705. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Kuno-Maekawa, M.; Sangawa, H.; Uehara, S.; Kozaki, K.; Nomura, N.; Egawa, H.; Shiraki, K. Mechanism of action of T-705 against influenza virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streeter, D.G.; Witkowski, J.T.; Khare, G.P.; Sidwell, R.W.; Bauer, R.J.; Robins, R.K.; Simon, L.N. Mechanism of action of 1- -D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide (Virazole), a new broad-spectrum antiviral agent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1973, 70, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smee, D.F.; Hurst, B.L.; Wong, M.H.; Bailey, K.W.; Tarbet, E.B.; Morrey, J.D.; Furuta, Y. Effects of the combination of favipiravir (T-705) and oseltamivir on influenza a virus infections in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.C.; Cheung, C.Y.; Chui, W.H.; Tsao, S.W.; Nicholls, J.M.; Chan, Y.O.; Chan, R.W.; Long, H.T.; Poon, L.L.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S. Proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by influenza A (H5N1) viruses in primary human alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 2005, 11, 1–135. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, M.D.; Simmons, C.P.; Thanh, T.T.; Hien, V.M.; Smith, G.J.; Chau, T.N.; Hoang, D.M.; Chau, N.V.; Khanh, T.H.; Dong, V.C.; Qui, P.T.; Cam, B.V.; Ha, do Q.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S.; Chinh, N.T.; Hien, T.T.; Farrar, J. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia . Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 1203–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.J.; Chan, K.W.; Lin, Y.P.; Zhao, G.Y.; Chan, C.; Zhang, H.J.; Chen, H.L.; Wong, S.S.; Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C.; Chan, K.H.; Jin, D.Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Delayed antiviral plus immunomodulator treatment still reduces mortality in mice infected by high inoculum of influenza A/H5N1 virus. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U S A 2008, 105, 8091–8096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghezzi, P.; Ungheri, D. Synergistic combination of N-acetylcysteine and ribavirin to protect from lethal influenza viral infection in a mouse model. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2004, 17, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garozzo, A.; Tempera, G.; Ungheri, D.; Timpanaro, R.; Castro, A. N-acetylcysteine synergizes with oseltamivir in protecting mice from lethal influenza infection. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2007, 20, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Serkedjieva, J.; Ivanova, E. Combined protective effect of an immunostimulatory bacterial preparation and rimantadine in experimental influenza A virus infection. Acta Virol. 1997, 41, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kohno, S.; Yen, M.Y.; Cheong, H.J.; Hirotsu, N.; Ishida, T.; Kadota, J.; Mizuguchi, M.; Kida, H.; Shimada, J. Single-intravenous peramivir vs. oral oseltamivir to treat acute, uncomplicated influenza in the outpatient setting: a phase III randomized, double-blind trial . In Proceedings of the 49th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- GlaxoSmithKline. An open-label, multi-center, single arm study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of intravenous zanamivir in the treatment of hospitalized adult, adolescent and pediatric subjects with confirmed influenza infection . Available online: http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/protocol_detail.jsp?protocolId=113678&studyId=29102&compound=Zanamivir (accessed on 20 April 2010).

- Kubo, S.; Tomozawa, T.; Kakuta, M.; Tokumitsu, A.; Yamashita, M. Laninamivir prodrug CS-8958, a long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor, shows superior anti-influenza virus activity after a single administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiso, M.; Kubo, S.; Ozawa, M.; Le, Q.M.; Nidom, C.A.; Yamashita, M.; Kawaoka, Y. Efficacy of the new neuraminidase inhibitor CS-8958 against H5N1 influenza viruses . PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biota Holdings. LANI phase II completed-phase III scheduled (press release 2008). Available online: http://www.biota.com.au/uploaded/154/1021393_18laniphaseiicompleted3Dp.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2010) .

- Sugaya, N.; Ohashi, Y. Long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor laninamivir octanoate (CS-8958) versus oseltamivir as treatment for children with influenza virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakhov, M.P.; Aschenbrenner, L.M.; Smee, D.F.; Wandersee, M.K.; Sidwell, R.W.; Gubareva, L.V.; Mishin, V.P.; Hayden, F.G.; Kim, D.H.; Ing, A.; Campbell, E.R.; Yu, M.; Fang, F. Sialidase fusion protein as a novel broad-spectrum inhibitor of influenza virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 1470–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belser, J.A.; Lu, X.; Szretter, K.J.; Jin, X.; Aschenbrenner, L.M.; Lee, A.; Hawley, S.; Kim, do H.; Malakhov, M.P.; Yu, M.; Fang, F.; Katz, J.M. DAS181, a novel sialidase fusion protein, protects mice from lethal avian influenza H5N1 virus infection . J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NexBio. NexBio Initiates Phase II Trial of DAS181 (Fludase®*) for Treatment of Influenza, Including Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1), 2010. Available online: http://www.nexbio.com/docs/DAS181_Phase_2_Press_Release_010710.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2010).

- O'Keefe, B.R.; Smee, D.F.; Turpin, J.A.; Saucedo, C.J.; Gustafson, K.R.; Mori, T.; Blakeslee, D.; Buckheit, R.; Boyd, M.R. Potent anti-influenza activity of cyanovirin-N and interactions with viral hemagglutinin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2518–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.