Porcine Cytomegalovirus/Porcine Roseolovirus, Previously Transmitted During Xenotransplantation, Does Not Infect Human 293T and Mouse Cells with Impaired Antiviral Defense

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PCMV/PRV-Producing PFT Cells

2.2. Hygromycin-Resistant Human Cells

2.3. Hygromycin-Resistant Mouse Cells

2.4. Transfection of PFT Cells

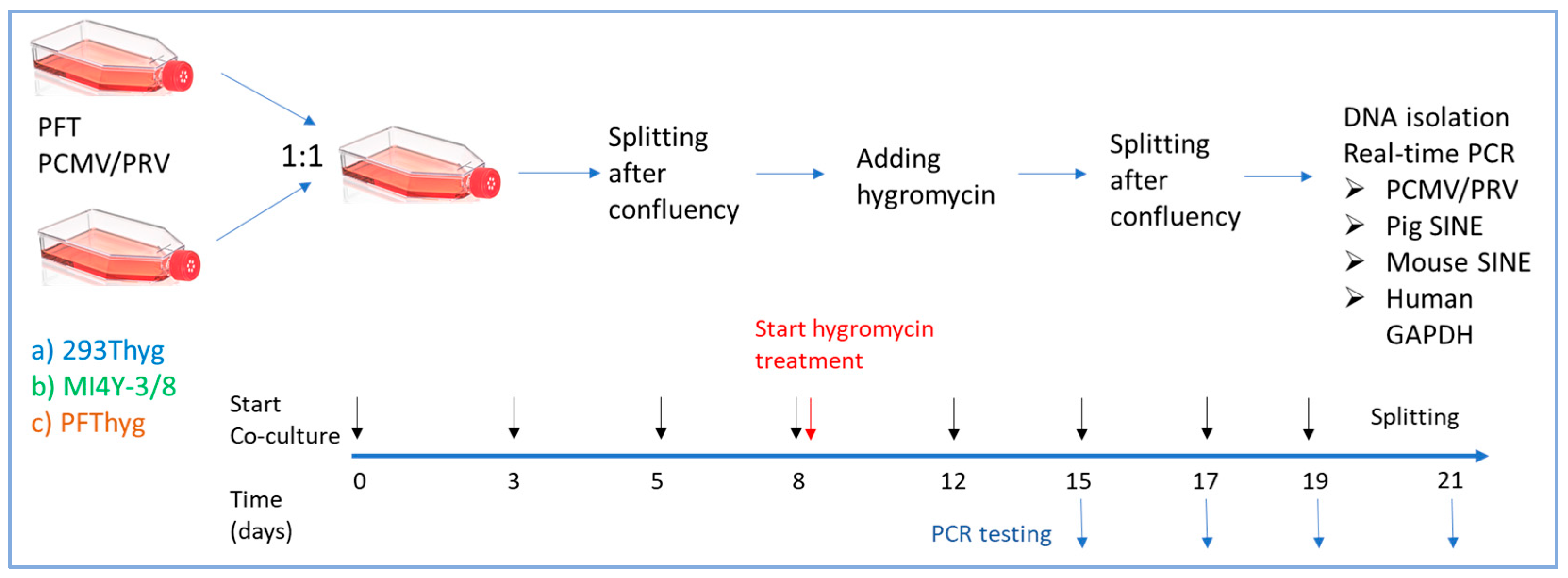

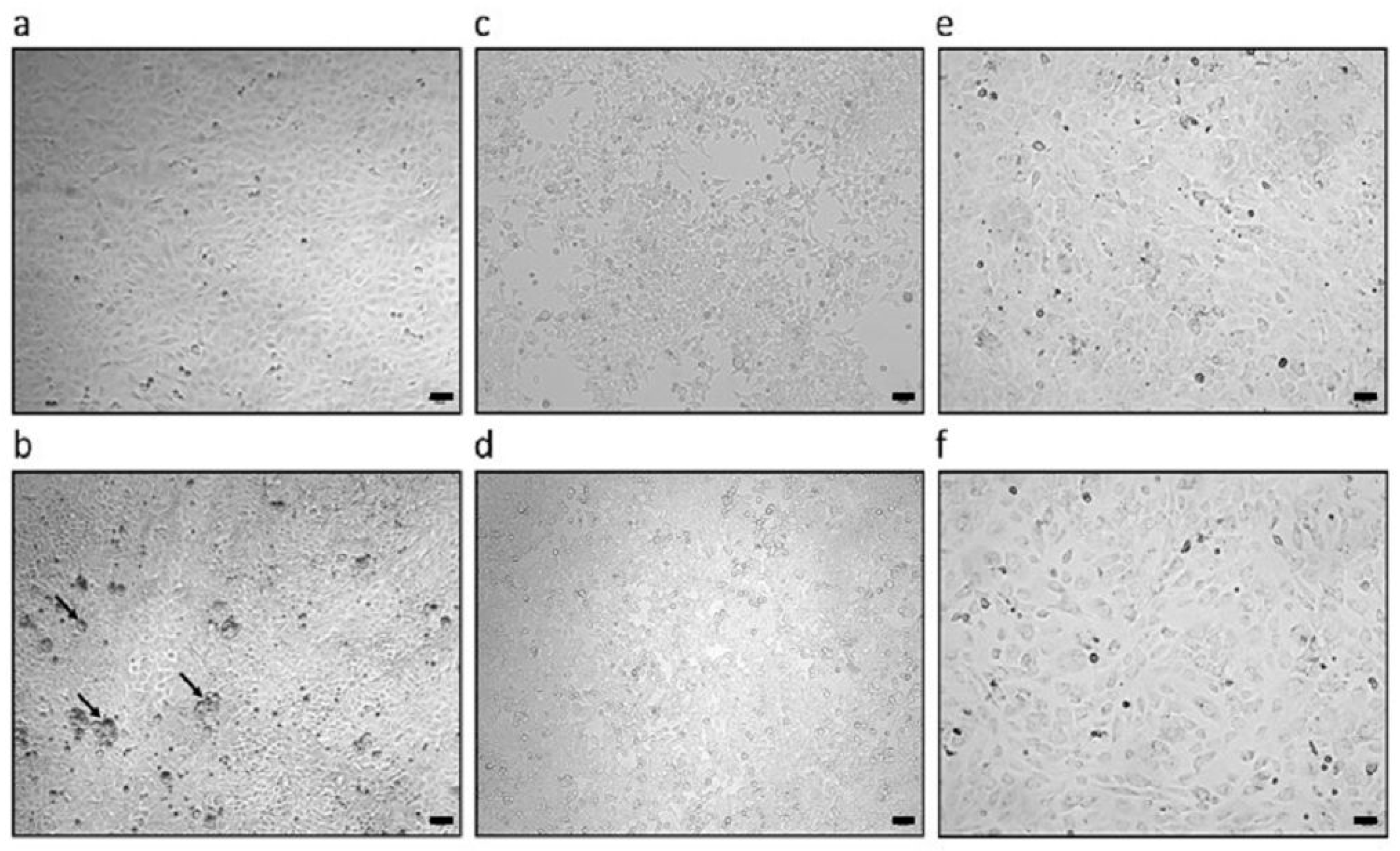

2.5. Co-Cultivation and Selection

2.6. Cell-Free Infection

2.7. Virus Pelleting

2.8. DNA Isolation

2.9. Real-Time PCR for PCMV/PRV, GAPDH, and SINE

2.10. Microscopy

| Primers and Probes Used for Real-Time PCR | Sequence 5′-3′ | Nucleotide Position | Accession Number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCMV/PRV fw PCMV/PRV rev PCMV/PRV probe | ACTTCGTCGCAGCTCATCTGA GTTCTGGGATTCCGAGGTTG 6FAM-CAGGGCGGCGGTCGAGCTC-BHQ1 | 45,206–45,226 45,268–45,249 45,247–45,229 | AF268039 | Mueller et al., 2002 [26] |

| hGAPDH fw hGAPDH rev hGAPDH probe | GGCGATGCTGGCGCTGAGTAC TGGTTCACACCCATGACGA HEX-CTTCACCACCATGGAGAAGGCTGGG-BHQ1 | 3568–3587 3803–3783 3655–3678 | AF261085 | Behrendt et al., 2009 [27] |

| pGAPDH fw pGAPDH rev pGAPDH probe | GATCGAGTTGGGGCTGTGACT ACATGGCCTCCAAGGAGTAAGA HEX-CCACCAACCCCAGCAAGAG-BHQ | 1083–1104 1188–1168 1114–1137 | NM_001206359.1 | Duvigneau et al., 2005 [28] |

| PRE-1 fw PRE-1 rev PRE-1 probe | GACTAGGAACCATGAGGTTGCG AGCCTACACCACAGCCACAG FAM-TTTGATCCCTGGCCTTGCTCAGTGG-BHQ1 | 37–58 61–85 151–170 | Y00104 | Walker et al., 2003 [29] |

| SINE B1 fw SINE B1 rev SINE B1 probe | TGGCGCACGCCTTTAATC TGGCCTCGAACTCAGAATCC 6FAM-ACTCGGGAGGCAGAGG-BHQ1 | n.a. | n.a. | Gualtieri et al., 2013 [30] |

| PERV-C fw PERV-C rev | CTGACCTGGATTAGAACTGG ATGTTAGAGGATGGTCCTGG | 6606–6625 6867–6886 | AM229312 | Takeuchi et al., 1998 [31] |

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of PCMV/PRV Used in the Infection Studies

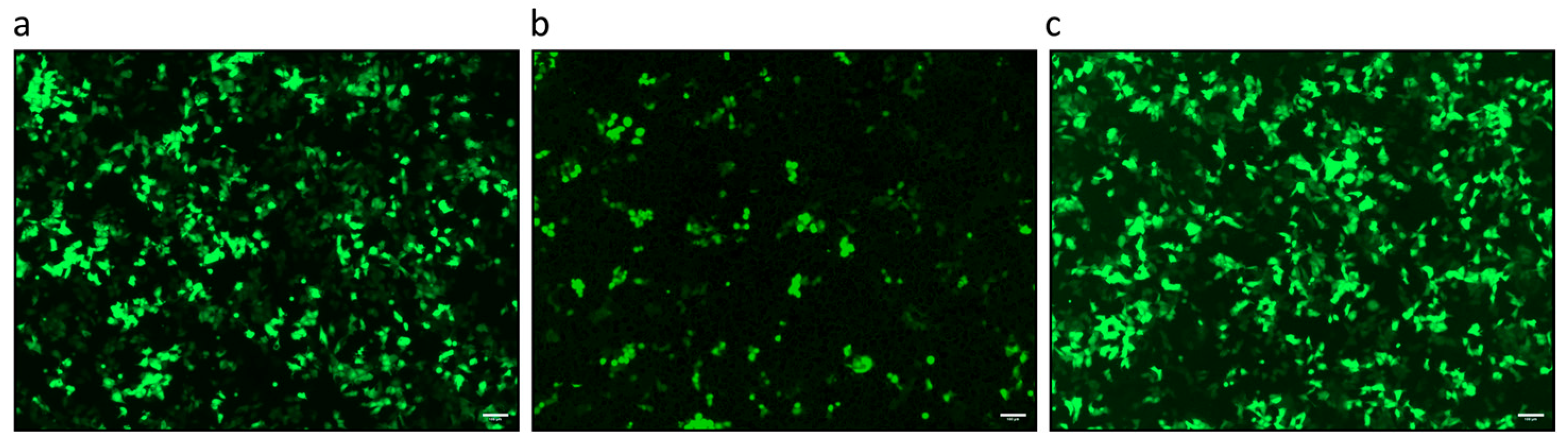

3.2. PCMV/PRV Infection of Hygromycin-Resistant PFT Cells

3.3. Failure to Infect Human Cells

3.4. Failure to Infect Mouse Cells

3.5. Infection of PFT Cells by Supernatant from PCMV/PRV-Producing PFT Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| PERV | Porcine endogenous retrovirus |

| PCMV/PRV | Porcine cytomegalovirus/porcine reoseolovirus |

| PFT | Porcine fallopian tube |

| SINE | Short Interspersed Nuclear Element |

| SuHV-2 | Suid herpesvirus 2 |

References

- Cooper, D.K.C.; Pierson, R.N., 3rd. Milestones on the path to clinical pig organ xenotransplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2023, 23, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. Virus Safety of Xenotransplantation. Viruses 2022, 14, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, J.A. Prevention of infection in xenotransplantation: Designated pathogen-free swine in the safety equation. Xenotransplantation 2020, 27, e12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J.; Bigley, T.M.; Phan, T.L.; Zimmermann, C.; Zhou, X.; Kaufer, B.B. Comparative Analysis of Roseoloviruses in Humans, Pigs, Mice, and Other Species. Viruses 2019, 11, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, B.P.; Goerlich, C.E.; Singh, A.K.; Rothblatt, M.; Lau, C.L.; Shah, A.; Lorber, M.; Grazioli, A.; Saharia, K.K.; Hong, S.N.; et al. Genetically Modified Porcine-to-Human Cardiac Xenotransplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezdimirović, N.; Savić, B.; Milovanović, B.; Glišić, D.; Ninković, M.; Kureljušić, J.; Maletić, J.; Aleksić Radojković, J.; Kasagić, D.; Milićević, V. Molecular Detection of Porcine Cytomegalovirus, Porcine Parvovirus, Aujeszky Disease Virus and Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus in Wild Boars Hunted in Serbia during 2023. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.; Menandro, M.L.; Franzo, G.; Krabben, L.; Marino, S.F.; Kaufer, B.; Denner, J. Presence of porcine cytomegalovirus, a porcine roseolovirus, in wild boars in Italy and Germany. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhelum, H.; Kaufer, B.; Denner, J. Application of Methods Detecting Xenotransplantation-Relevant Viruses for Screening German Slaughterhouse Pigs. Viruses 2024, 16, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhelum, H.; Papatsiros, V.; Papakonstantinou, G.; Krabben, L.; Kaufer, B.; Denner, J. Screening for Viruses in Indigenous Greek Black Pigs. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Meng, X.J. Hepatitis E virus: Host tropism and zoonotic infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. Xenotransplantation and Hepatitis E virus. Xenotransplantation 2015, 22, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Lu, M.L.; Guo, C.; Guo, Z.M.; Yuan, J.; Lu, J.H. An occupational risk of hepatitis E virus infection in the workers along the meat supply chains in Guangzhou, China. One Health 2022, 14, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitteker, J.L.; Dudani, A.K.; Tackaberry, E.S. Human fibroblasts are permissive for porcine cytomegalovirus in vitro. Transplantation 2008, 86, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.W.; Galbraith, D.; McEwan, P.; Onions, D. Evaluation of porcine cytomegalovirus as a potential zoonotic agent in xenotransplantation. Transplant. Proc. 1999, 31, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. Reduction of the survival time of pig xenotransplants by porcine cytomegalovirus. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillant, A.M.; Genest, P.; Greig, A.S. Growth characteristics of a cell line derived from the pig oviduct. Can. J. Microbiol. 1975, 21, 2094–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillant, A.M.; Greig, A.S. Type C virus production by a continuous line of pig oviduct cells (PFT). J. Gen. Virol. 1975, 27, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H.; Tajima, T.; Hironao, T.; Kajikawa, T.; Kotani, T. Replication of porcine cytomegalovirus in the 19-PFT cell line. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1992, 54, 1209–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, H.; Matsuzaki, S. Influence of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate on replication of porcine cytomegalovirus in the 19-PFT-F cell line. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1996, 58, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillant, A.M.; Dulac, G.C.; Willis, N.; Girard, A.; Greig, A.S.; Boulanger, P. Viral susceptibility of a cell line derived from the pig oviduct. Can. J. Comp. Med. 1975, 39, 450–456. [Google Scholar]

- Denner, J.; Schwinzer, R.; Pokoyski, C.; Kaufer, B.B.; Dierkes, B.; Lovlesh, L. Further evidence for the immunosuppressive activity of the transmembrane envelope protein p15E of the porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV). Research Square 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, G.J.; Green, H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J. Cell Biol. 1963, 17, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Reis, L.F.; Pavlovic, J.; Aguzzi, A.; Schäfer, R.; Kumar, A.; Williams, B.R.; Aguet, M.; Weissmann, C. Deficient signaling in mice devoid of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 6095–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, T. Functional Characterization of the Potential Immune Evasion Proteins pUL49.5 and p012 of Marek’s Disease Virus (MDV). Ph.D. Thesis, Free University Berlin, Freie Universität, Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.J.; Barth, R.N.; Yamamoto, S.; Kitamura, H.; Patience, C.; Yamada, K.; Cooper, D.K.; Sachs, D.H.; Kaur, A.; Fishman, J.A. Activation of cytomegalovirus in pig-to-primate organ xenotransplantation. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 4734–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, R.; Fiebig, U.; Norley, S.; Gürtler, L.; Kurth, R.; Denner, J. A neutralization assay for HIV-2 based on measurement of provirus integration by duplex real-time PCR. J. Virol. Methods 2009, 159, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvigneau, J.C.; Hartl, R.T.; Groiss, S.; Gemeiner, M. Quantitative simultaneous multiplex real-time PCR for the detection of porcine cytokines. J. Immunol. Methods 2005, 306, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.A.; Hughes, D.A.; Anders, B.A.; Shewale, J.; Sinha, S.K.; Batzer, M.A. Quantitative intra-short interspersed element PCR for species-specific DNA identification. Anal. Biochem. 2003, 316, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, A.; Andreola, F.; Sciamanna, I.; Sinibaldi-Vallebona, P.; Serafino, A.; Spadafora, C. Increased expression and copy number amplification of LINE-1 and SINE B1 retrotransposable elements in murine mammary carcinoma progression. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 1882–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Patience, C.; Magre, S.; Weiss, R.A.; Banerjee, P.T.; Le Tissier, P.; Stoye, J.P. Host range and interference studies of three classes of pig endogenous retrovirus. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 9986–9991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.; Gulich, B.; Keßler, B.; Längin, M.; Fishman, J.A.; Wolf, E.; Boller, K.; Tönjes, R.R.; Godehardt, A.W. PCR and peptide based PCMV detection in pig—Development and application of a combined testing procedure differentiating newly from latent infected pigs. Xenotransplantation 2023, 30, e12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollackner, B.; Mueller, N.J.; Houser, S.; Qawi, I.; Soizic, D.; Knosalla, C.; Buhler, L.; Dor, F.J.; Awwad, M.; Sachs, D.H.; et al. Porcine cytomegalovirus and coagulopathy in pig-to-primate xenotransplantation. Transplantation 2003, 75, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhelum, H.; Bender, M.; Reichart, B.; Mokelke, M.; Radan, J.; Neumann, E.; Krabben, L.; Abicht, J.M.; Kaufer, B.; Längin, M.; et al. Evidence for Microchimerism in Baboon Recipients of Pig Hearts. Viruses 2023, 15, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Tasaki, M.; Sekijima, M.; Wilkinson, R.A.; Villani, V.; Moran, S.G.; Cormack, T.A.; Hanekamp, I.M.; Hawley, R.J.; Arn, J.S.; et al. Porcine cytomegalovirus infection is associated with early rejection of kidney grafts in a pig to baboon xenotransplantation model. Transplantation 2014, 98, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekijima, M.; Waki, S.; Sahara, H.; Tasaki, M.; Wilkinson, R.A.; Villani, V.; Shimatsu, Y.; Nakano, K.; Matsunari, H.; Nagashima, H.; et al. Results of life-supporting galactosyltransferase knockout kidneys in cynomolgus monkeys using two different sources of galactosyltransferase knockout swine. Transplantation 2014, 98, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J.; Längin, M.; Reichart, B.; Krüger, L.; Fiebig, U.; Mokelke, M.; Radan, J.; Mayr, T.; Milusev, A.; Luther, F.; et al. Impact of porcine cytomegalovirus on long-term orthotopic cardiac xenotransplant survival. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, U.; Abicht, J.M.; Mayr, T.; Längin, M.; Bähr, A.; Guethoff, S.; Falkenau, A.; Wolf, E.; Reichart, B.; Shibahara, T.; et al. Distribution of Porcine Cytomegalovirus in Infected Donor Pigs and in Baboon Recipients of Pig Heart Transplantation. Viruses 2018, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. Zoonosis and xenozoonosis in xenotransplantation: A proposal for a new classification. Zoonoses Public Health 2023, 70, 578–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, U.; Holzer, A.; Ivanusic, D.; Plotzki, E.; Hengel, H.; Neipel, F.; Denner, J. Antibody Cross-Reactivity between Porcine Cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Human Herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6). Viruses 2017, 9, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Scobie, L.; Goerlich, C.E.; Grazioli, A.; Saharia, K.; Crossan, C.; Burke, A.; Drachenberg, C.; Oguz, C.; et al. Graft dysfunction in compassionate use of genetically engineered pig-to-human cardiac xenotransplantation: A case report. Lancet 2023, 402, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, W.; Dayaram, A.; Greenwood, A.D.; Osterrieder, N. How Host Specific Are Herpesviruses? Lessons from Herpesviruses Infecting Wild and Endangered Mammals. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018, 5, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, M.G.; Alcendor, D.J.; St George, K.; Rinaldo, C.R., Jr.; Ehrlich, G.D.; Becich, M.J.; Hayward, G.S. Distinguishing baboon cytomegalovirus from human cytomegalovirus: Importance for xenotransplantation. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 176, 1476–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, M.G.; Jenkins, F.J.; St George, K.; Nalesnik, M.A.; Starzl, T.E.; Rinaldo, C.R., Jr. Detection of infectious baboon cytomegalovirus after baboon-to-human liver xenotransplantation. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 2825–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degré, M.; Ranneberg-Nilsen, T.; Beck, S.; Rollag, H.; Fiane, A.E. Human cytomegalovirus productively infects porcine endothelial cells in vitro. Transplantation 2001, 72, 1334–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettenleiter, T.C.; Ehlers, B.; Müller, T.; Yoon, K.-J.; Teifke, J.P. Herpesviruses. In Diseases of Swine, 10th ed.; Zimmerman, J.J., Karriker, L.A., Ramirez, A., Schwartz, K.J., Stevenson, G.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Ames, IA, USA, 2012; pp. 1534–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Rausell, A.; Muñoz, M.; Martinez, R.; Roger, T.; Telenti, A.; Ciuffi, A. Innate immune defects in HIV permissive cell lines. Retrovirology 2016, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroozmand, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Khamsri, B.; Fujita, M.; Uchiyama, T.; Adachi, A. Generation and characterization of APOBEC3G-positive 293T cells for HIV-1 Vif study. J. Med. Invest. 2007, 54, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Dinh, P.X.; Beura, L.K.; Pattnaik, A.K. Induction of interferon and interferon signaling pathways by replication of defective interfering particle RNA in cells constitutively expressing vesicular stomatitis virus replication proteins. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 4826–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Diep, J.; Feng, N.; Ren, L.; Li, B.; Ooi, Y.S.; Wang, X.; Brulois, K.F.; Yasukawa, L.L.; Li, X.; et al. STAG2 deficiency induces interferon responses via cGAS-STING pathway and restricts virus infection. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.B.; Sumner, R.P.; Rodriguez-Plata, M.T.; Rasaiyaah, J.; Milne, R.S.; Thrasher, A.J.; Qasim, W.; Towers, G.J. Lentiviral Vector Production Titer Is Not Limited in HEK293T by Induced Intracellular Innate Immunity. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 17, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterholzner, L.; Keating, S.E.; Baran, M.; Horan, K.A.; Jensen, S.B.; Sharma, S. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staeheli, P.; Haller, O. Human MX2/MxB: A Potent Interferon-Induced Postentry Inhibitor of Herpesviruses and HIV-1. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e709–e718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.D.; Wu, J.; Gao, D.; Wang, H.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.J. Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science 2018, 341, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindel, A.; Sadler, A. The role of protein kinase R in the interferon response. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011, 31, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovanessian, A.G. On the discovery of interferon-inducible, double-stranded RNA activated enzymes: The 2′-5′oligoadenylate synthetases and the protein kinase PKR. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007, 18, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, R.M. Viral proteins that bind double-stranded RNA: Countermeasures against host antiviral responses. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014, 34, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.A.; Meurs, E.F.; Esteban, M. The dsRNA protein kinase PKR: Virus and cell control. Biochimie 2007, 89, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.; Berg, M. The multiple faces of protein kinase R in antiviral defense. Virulence 2013, 4, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. Co-Cultivation Assays for Detecting Infectious Human-Tropic Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses (PERVs). Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Gu, L.; Gao, Y.; Pan, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Yu, D.; Han, X.; Qian, L.; et al. Young SINEs in pig genomes impact gene regulation, genetic diversity, and complex traits. Commun Biol. 2023, 6, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Guo, T.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, L. Origin, evolution, and tissue-specific functions of the porcine repetitive element 1. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2022, 54, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Mou, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Han, L.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, W.; et al. The sequence and analysis of a Chinese pig genome. Gigascience 2012, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiyanagi, K.; Li, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Ichiyanagi, T.; Fukuda, K.; Kitayama, J.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S.; Nakano, T.; Yabuta, Y.; et al. Locus- and domain-dependent control of DNA methylation at mouse B1 retrotransposons during male germ cell development. Genome Res. 2011, 21, 2058–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterston, R.H.; Lindblad-Toh, K.; Birney, E.; Rogers, J.; Abril, J.F.; Agarwal, P.; Agarwala, R.; Ainscough, R.; Alexandersson, M.; An, P.; et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 2002, 420, 520–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. What does the PERV copy number tell us? Xenotransplantation 2022, 29, e12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. How Does a Porcine Herpesvirus, PCMV/PRV, Induce a Xenozoonosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. The transmembrane proteins contribute to immunodeficiencies induced by HIV-1 and other retroviruses. AIDS 2014, 28, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell Line | PCMV/PRV | PERV-C | pGAPDH |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFT | n.d. | - | 105.4 |

| PFT-PCMV/PRV | 104 | - | 105.4 |

| Supernatant | PCMV/PRV |

|---|---|

| Direct | n.d. |

| Virus pellet | 102.4 |

| Cell Lines | PCMV PRV | PRE-1 (Porcine SINE) | SINE B1 (Murine SINE) | Human GAPDH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFT PCMV/PRV cells | 104 | 108 | n.a. | n.a. |

| PFThyg cells after co-culture with PFT PCMV/PRV cells and subsequent selection | 104 | 108 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 293Thyg cells after co-culture with PFT PCMV/PRV cells and subsequent selection | n.d. | n.d. | n.a. | 105.2 |

| MI4Y-3/8 cells after co-culture with PFT PCMV/PRV cells and subsequent selection | n.d. | n.d. | 106.9 | n.a. |

| Cell Line | PCMV/PRV | pGAPDH |

|---|---|---|

| PFT cells after treatment with supernatant from PCMV/PRV-producing cells | 103.4 | 104.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jhelum, H.; Schäfer, R.; Kaufer, B.B.; Denner, J. Porcine Cytomegalovirus/Porcine Roseolovirus, Previously Transmitted During Xenotransplantation, Does Not Infect Human 293T and Mouse Cells with Impaired Antiviral Defense. Viruses 2026, 18, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010021

Jhelum H, Schäfer R, Kaufer BB, Denner J. Porcine Cytomegalovirus/Porcine Roseolovirus, Previously Transmitted During Xenotransplantation, Does Not Infect Human 293T and Mouse Cells with Impaired Antiviral Defense. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleJhelum, Hina, Reinhold Schäfer, Benedikt B. Kaufer, and Joachim Denner. 2026. "Porcine Cytomegalovirus/Porcine Roseolovirus, Previously Transmitted During Xenotransplantation, Does Not Infect Human 293T and Mouse Cells with Impaired Antiviral Defense" Viruses 18, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010021

APA StyleJhelum, H., Schäfer, R., Kaufer, B. B., & Denner, J. (2026). Porcine Cytomegalovirus/Porcine Roseolovirus, Previously Transmitted During Xenotransplantation, Does Not Infect Human 293T and Mouse Cells with Impaired Antiviral Defense. Viruses, 18(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010021