Rapid LAMP-Based Detection of Mixed Begomovirus Infections in Field-Grown Tomato Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. TYLCV, TLV and ToMoTV Infectious Clones

2.2. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.3. Virus Inoculation

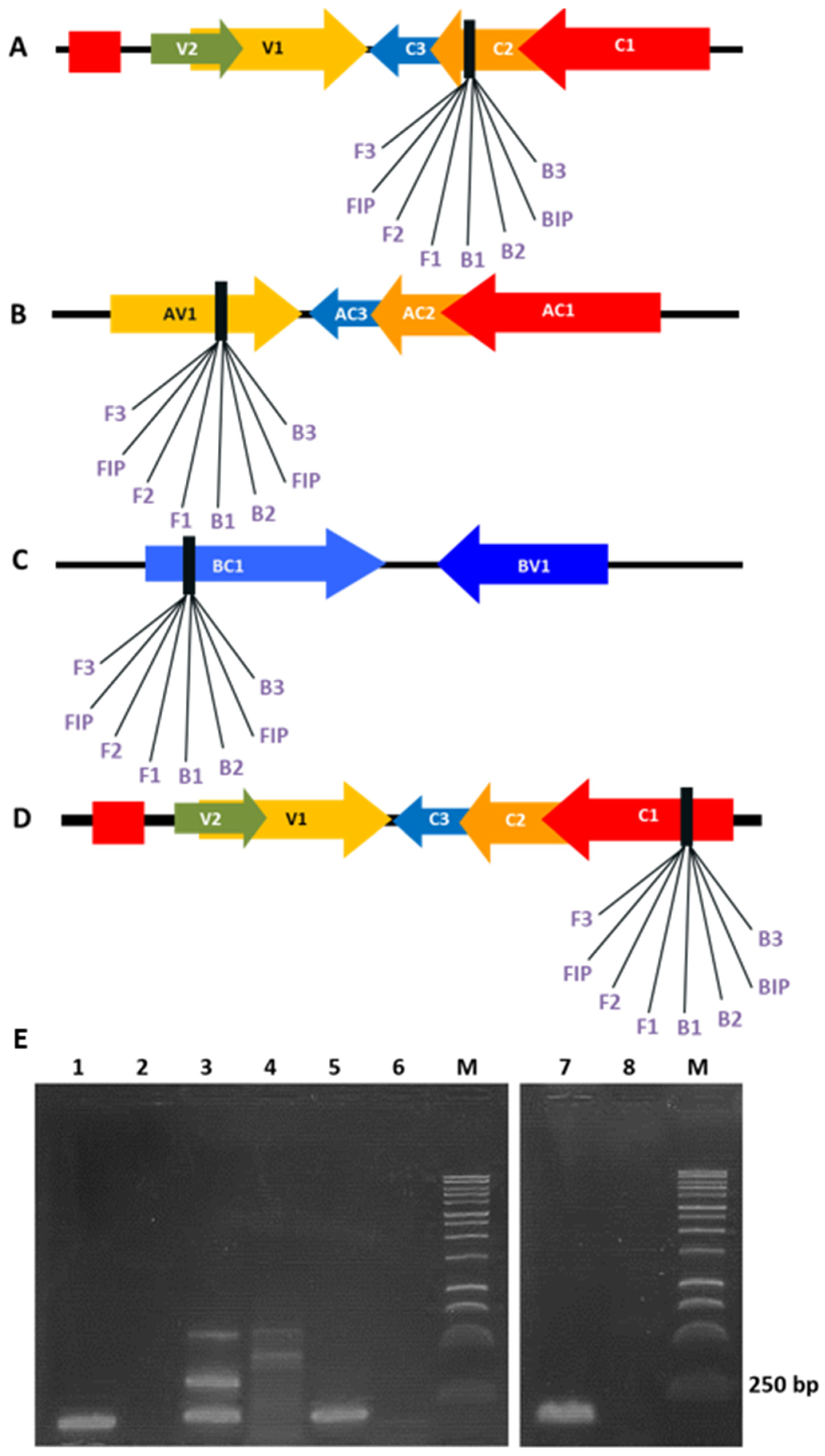

2.4. LAMP Assays

2.5. Dot Blot Hybridization

2.6. PCR Assays

2.7. Field Trials

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of LAMP Primers Using Template DNA from Agroinoculated N. benthamiana and Tomato Plants

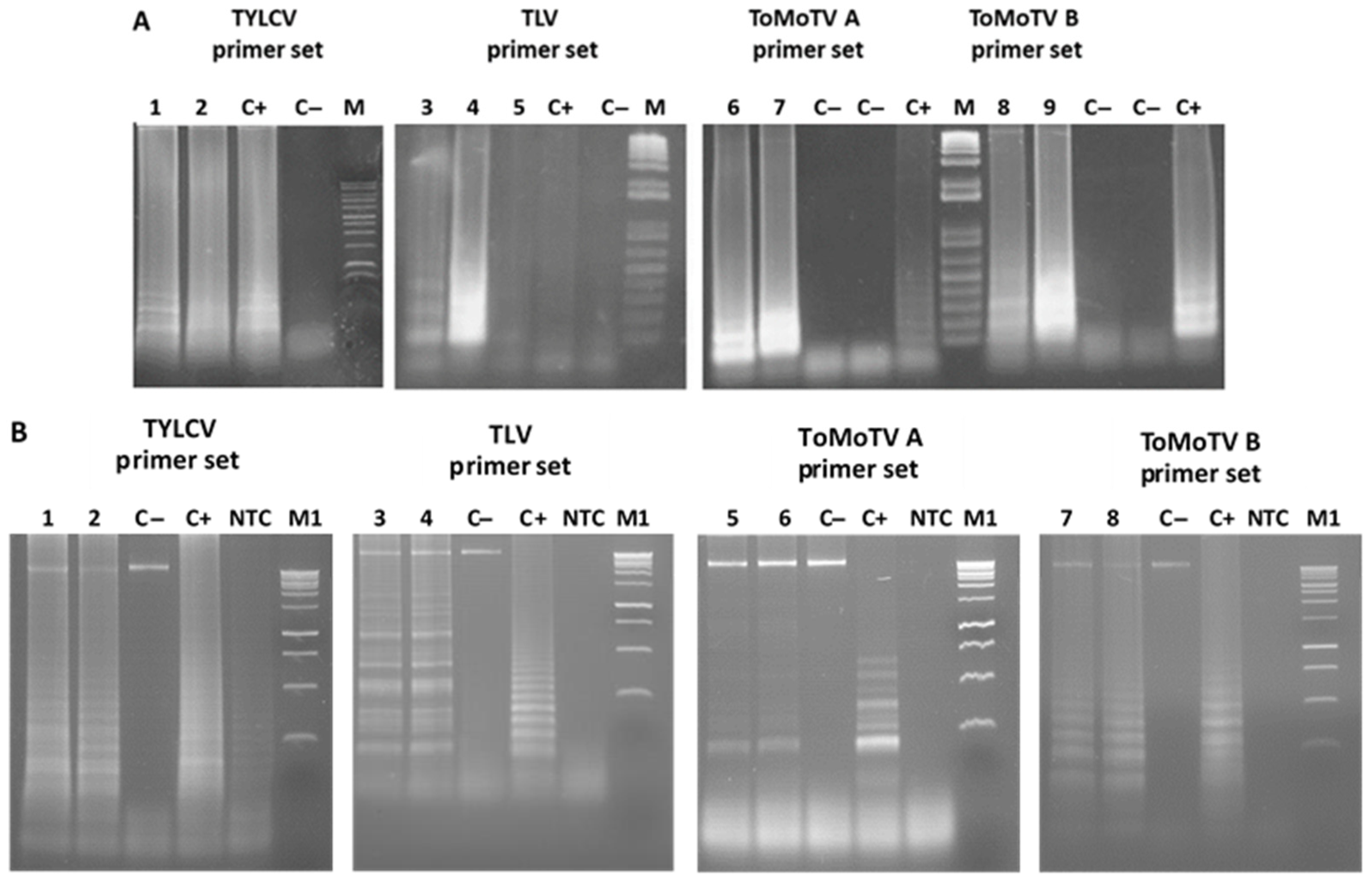

3.2. Specificity of LAMP Assays

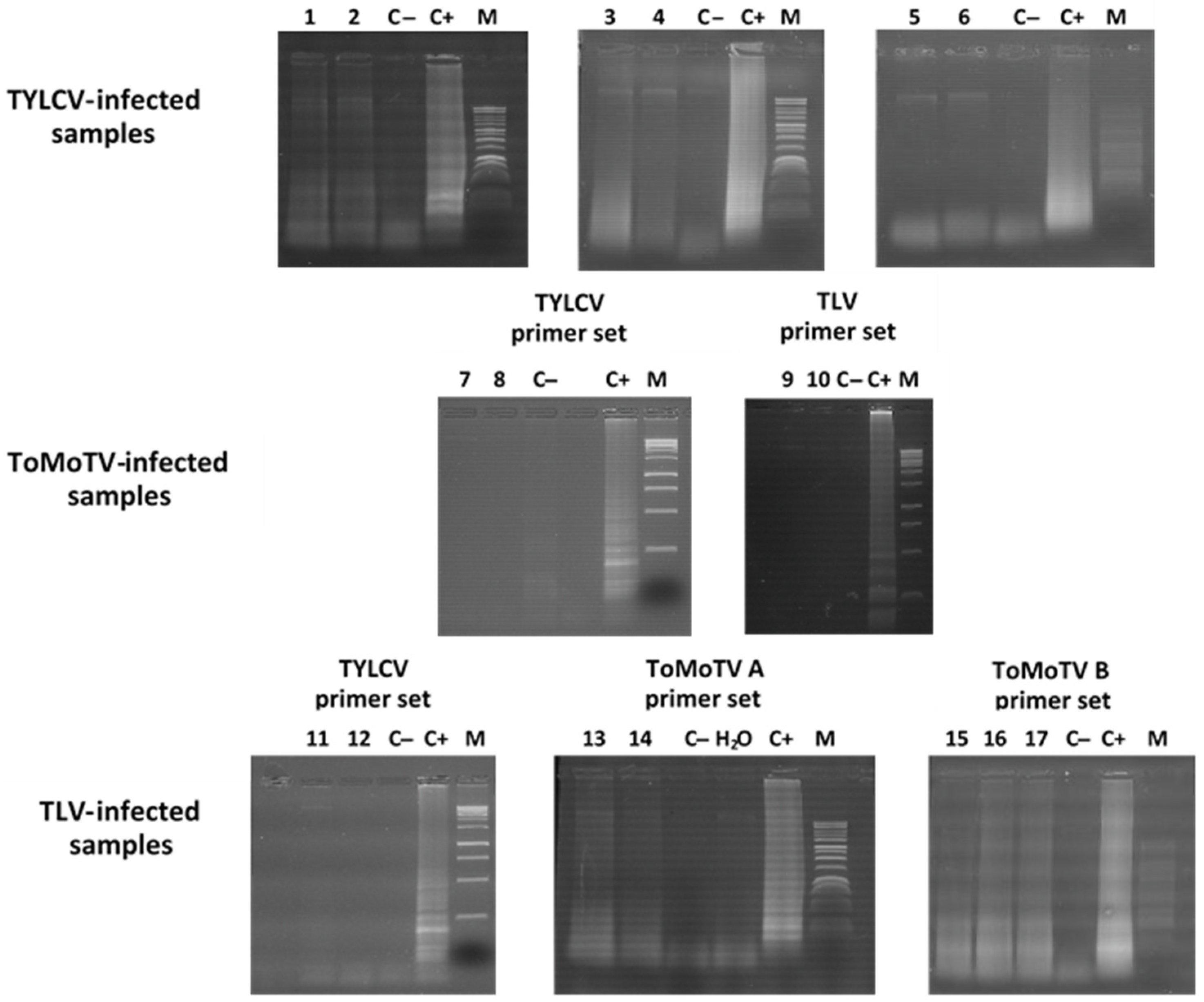

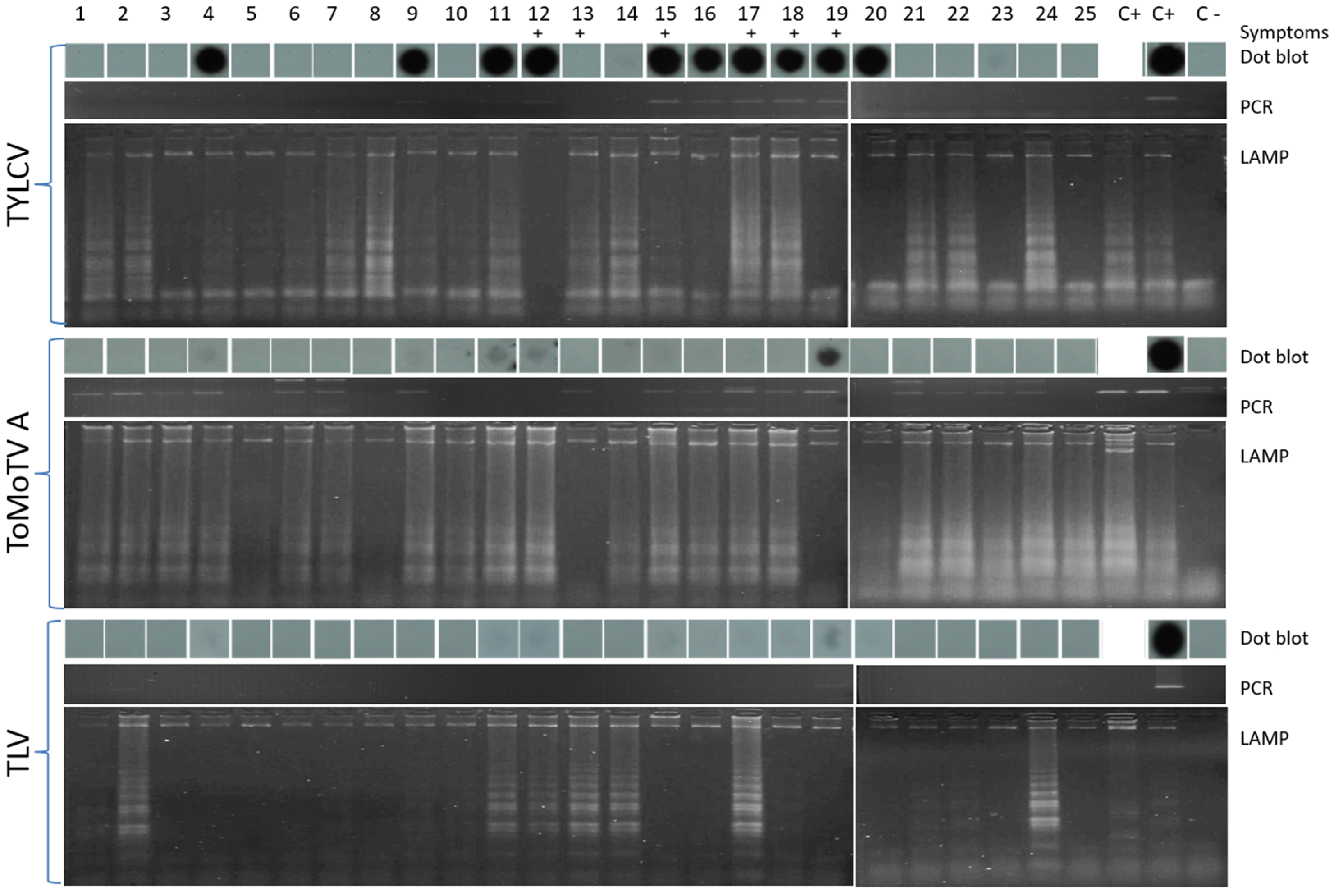

3.3. Detection of TYLCV, ToMoTV, and TLV in Field-Grown Tomato Plants by LAMP

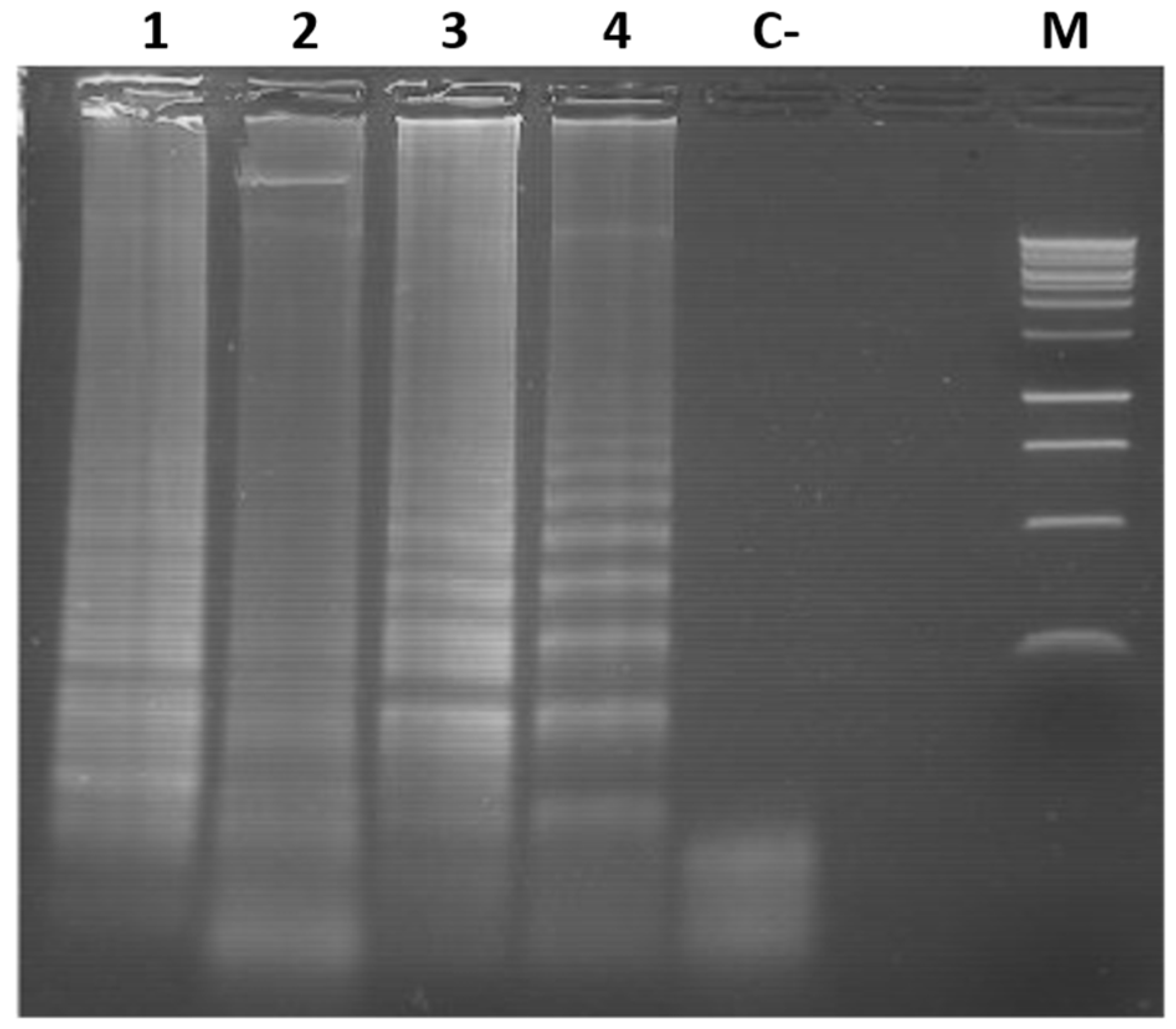

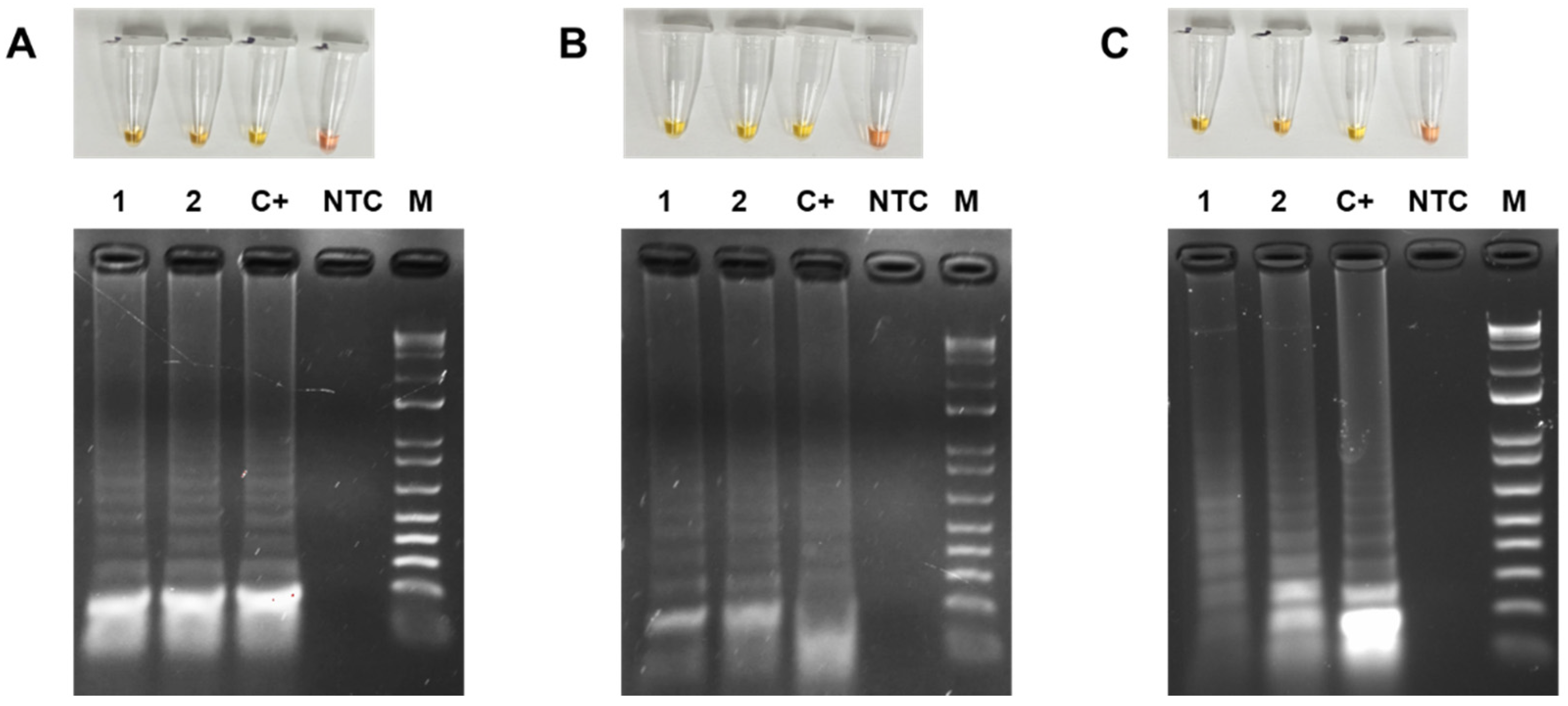

3.4. Colorimetric LAMP Detection of TYLCV, ToMoTV and TLV in Agro-Infected Tomato Plants

3.5. Limit of Detection (LOD) of the Colorimetric LAMP of TYLCV, ToMoTV and TLV

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zubiaur, Y.M.; Zabalgogeazcoa, I.; De Blas, C.; Sánchez, F.; Peralta, E.; Romero, J.; Ponz, F. Geminiviruses associated with diseased tomatoes in Cuba. J. Phytopathol. 1996, 144, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Guerra, O.; Dorestes, V.; Ramirez, N.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.; Oramas, P. Detection of TYLCV in Cuba. Plant Dis. 1996, 80, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Zubiaur, Y.; Quiñones, M.; Fonseca, D.; Potter, J.; Maxwell, D. First report of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus associated with beans, Phaseolus vulgaris, in Cuba. Plant Dis. 2002, 86, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaur, Y.M.; Fonseca, D.; Quiñones, M.; Palenzuela, I. Presence of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus infecting squash (Curcubita pepo) in Cuba. Plant Dis. 2004, 88, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Zubiaur, Y.; De Blas, C.; Quiñones, M.; Castellanos, C.; Peralta, E.; Romero, J. Havana tomato virus, a new bipartite geminivirus infecting tomatoes in Cuba. Arch. Virol. 1998, 143, 1757–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Guerra, O.; Peral, R.; Oramas, P.; Guevara, R.; Rivera-Bustamante, R. Taino tomato mottle virus, a new bipartite geminivirus from Cuba. Plant Dis. 1997, 81, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Hernández-Zepeda, C.; Trejo-Saavedra, D.; Carrillo-Tripp, J.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.; Martínez-Zubiaur, Y. Complete genome and pathogenicity of Tomato yellow leaf distortion virus, a bipartite begomovirus infecting tomato in Cuba. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 134, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zubiaur, Y.; Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Carrillo-Tripp, J.; Rivera-Bustamante, R. First report of Tomato chlorosis virus infecting tomato in single and mixed infections with Tomato yellow leaf curl virus in Cuba. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Zubiaur, Y.; Chang Sidorchuk, L.; González Alvarez, H.; Barboza Vargas, N.M.; González Arias, G. First molecular evidence of Tomato chlorotic spot virus infecting tomatoes in Cuba. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A.; Carlos, N.; Ruiz, Y.; Callard, D.; Sánchez, Y.; Ochagavía, M.E.; Seguin, J.; Malpica-López, N.; Hohn, T.; Lecca, M.R.; et al. Field trial and molecular characterization of RNAi-transgenic tomato plants that exhibit resistance to tomato yellow leaf curl geminivirus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2016, 29, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argüello-Astorga, G.; Guevara-González, R.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Rivera-Bustamante, R. Geminivirus replication origins have a group-specific organization of iterative elements: A model for replication. Virology 1994, 203, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.-J.; Ju, H.-J.; Noh, J. A review of detection methods for the plant viruses. Res. Plant Dis. 2014, 20, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Vásquez, J.A.; Puchades, A.V.; Elvira-González, L.; Jaén-Sanjur, J.N.; Carpino, C.; Rubio, L.; Galipienso, L. Fast detection by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of the three begomovirus species infecting tomato in Panama. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 151, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño, M.A.; Harmon, C.L.; Polston, J.E. Evaluation of recombinase polymerase amplification for detection of begomoviruses by plant diagnostic clinics. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.G.; Ragona, A.; Bertacca, S.; Montoya, M.A.M.; Panno, S.; Davino, S. Development of an in-field real-time LAMP assay for rapid detection of tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus. Plants 2023, 12, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasi, M.A.; Ojaghkandi, M.; Hemmatabadi, A.; Hamidi, F.; Aghaei, S. Development of colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid detection of the tomato yellow leaf curl virus. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahas, A.; Hassan, N.; Aman, R.; Marsic, T.; Wang, Q.; Ali, Z.; Mahfouz, M.M. LAMP-coupled CRISPR–Cas12a module for rapid and sensitive detection of plant DNA viruses. Viruses 2021, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuta, S.; Kato, S.; Yoshida, K.; Mizukami, Y.; Ishida, A.; Ueda, J.; Kanbe, M.; Ishimoto, Y. Detection of tomato yellow leaf curl virus by loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction. J. Virol. Methods 2003, 112, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, A.D.; Ramos, P.L.; Fernández, A.I.; Tiel, K.; Callard, D.; Sánchez, Y.; Pujol, M. Células de tabaco transgénico: Sistema permisivo para la evaluación de estrategias de resistencia al virus del enrollamiento foliar amarillo del tomate. Biotecnol. Apl. 2009, 26, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Collazo, C.; Ramos, P.L.; Chacón, O.; Borroto, C.J.; López, Y.; Pujol, M.; Thomma, B.P.; Hein, I.; Borrás-Hidalgo, O. Phenotypical and molecular characterization of the Tomato mottle Taino virus–Nicotiana megalosiphon interaction. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2005, 67, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfgen, R.; Willmitzer, L. Storage of competent cells for Agrobacterium transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 9877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooms, G.; Hooykaas, P.J.; Van Veen, R.J.; Van Beelen, P.; Regensburg-Tuïnk, T.J.; Schilperoort, R.A. Octopine Ti-plasmid deletion mutants of Agrobacterium tumefaciens with emphasis on the right side of the T-region. Plasmid 1982, 7, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 1990, 12, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Ramirez, E.; Sudarshana, M.; Gilbertson, R.L. Bean golden yellow mosaic virus from Chiapas, Mexico: Characterization, pseudorecombination with other bean-infecting geminiviruses and germ plasm screening. Phytopathology 2000, 90, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Sidas, D.A.; Vargas-Hernandez, B.Y.; Ramirez-Pool, J.A.; Nunez-Munoz, L.A.; Calderon-Perez, B.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, R.; Brieba, L.G.; Lira-Carmona, R.; Ferat-Osorio, E.; Lopez-Macias, C. Starting from scratch: Step-by-step development of diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2 detection by RT-LAMP. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, A.; Ramos, P.L.; Fiallo, E.; Callard, D.; Sánchez, Y.; Peral, R.; Rodríguez, R.; Pujol, M. Intron–hairpin RNA derived from replication associated protein C1 gene confers immunity to Tomato yellow leaf curl virus infection in transgenic tomato plants. Transgenic Res. 2006, 15, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapi-Nelson, M.; Wen, R.-H.; Ownley, B.; Hajimorad, M. Co-infection of soybean with Soybean mosaic virus and Alfalfa mosaic virus results in disease synergism and alteration in accumulation level of both viruses. Plant Dis. 2009, 93, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentería-Canett, I.; Xoconostle-Cázares, B.; Ruiz-Medrano, R.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Geminivirus mixed infection on pepper plants: Synergistic interaction between PHYVV and PepGMV. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvaudon, L.; De Moraes, C.M.; Mescher, M.C. Outcomes of co-infection by two potyviruses: Implications for the evolution of manipulative strategies. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20122959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syller, J. Facilitative and antagonistic interactions between plant viruses in mixed infections. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorkin, O.; Merits, A.; Lucchesi, J.; Solovyev, A.; Saarma, M.; Morozov, S.Y.; Mäkinen, K. Complementation of the movement-deficient mutations in potato virus X: Potyvirus coat protein mediates cell-to-cell trafficking of C-terminal truncation but not deletion mutant of potexvirus coat protein. Virology 2000, 270, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Lozano, J.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Fauquet, C.M.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Interactions between geminiviruses in a naturally occurring mixture: Pepper huasteco virus and Pepper golden mosaic virus. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodin, M.M.; Zaitlin, D.; Naidu, R.A.; Lommel, S.A. Nicotiana benthamiana: Its history and future as a model for plant–pathogen interactions. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Navas-Castillo, J. Molecular and biological characterization of a New World mono-/bipartite begomovirus/deltasatellite complex infecting Corchorus siliquosus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Martín, B.; Aragón-Caballero, L.; Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Navas-Castillo, J.; Moriones, E. Tomato leaf deformation virus, a novel begomovirus associated with a severe disease of tomato in Peru. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2011, 129, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgarejo, T.A.; Kon, T.; Rojas, M.R.; Paz-Carrasco, L.; Zerbini, F.M.; Gilbertson, R.L. Characterization of a new world monopartite begomovirus causing leaf curl disease of tomato in Ecuador and Peru reveals a new direction in geminivirus evolution. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 5397–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Campos, S.; Martínez-Ayala, A.; Márquez-Martín, B.; Aragón-Caballero, L.; Navas-Castillo, J.; Moriones, E. Fulfilling Koch’s postulates confirms the monopartite nature of tomato leaf deformation virus: A begomovirus native to the New World. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.O.; Melgarejo, T.A.; Vu, S.; Nakasu, E.Y.; Chen, L.-F.; Rojas, M.R.; Zerbini, F.M.; Inoue-Nagata, A.K.; Gilbertson, R.L. How to be a successful monopartite begomovirus in a bipartite-dominated world: Emergence and spread of tomato mottle leaf curl virus in Brazil. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e00725-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, M.; Albuquerque, L.; Maliano, M.; Souza, J.; Rojas, M.; Inoue-Nagata, A.; Gilbertson, R. Characterization of tomato leaf curl purple vein virus, a new monopartite New World begomovirus infecting tomato in Northeast Brazil. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romay, G.; Geraud-Pouey, F.; Chirinos, D.T.; Mahillon, M.; Gillis, A.; Mahillon, J.; Bragard, C. Tomato twisted leaf virus: A novel indigenous new world monopartite begomovirus infecting tomato in Venezuela. Viruses 2019, 11, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Ding, Y.; He, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, J.-K.; Lozano-Duran, R. A virus-encoded protein suppresses methylation of the viral genome through its interaction with AGO4 in the Cajal body. eLife 2020, 9, e55542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamin Filho, A.; Macedo, M.A.; Favara, G.M.; Bampi, D.; Oliveira, d.F.F.; Rezende, J.A. Amplifier Hosts May Play an Essential Role in Tomato Begomovirus Epidemics in Brazil. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crego-Vicente, B.; Diego del Olmo, M.; Muro, A.; Fernández-Soto, P. Multiplexing LAMP Assays: A Methodological Review and Diagnostic Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virus-Primer | Gene/Position | Sequence 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| TYLCV-F3 | C3/1234-1254 | TCTTAAGAAACGACCAGTCT |

| TYLCV-B3 | C3/1409-1432 | TTTATCTGGGAGATAATCAATCC |

| TYLCV-FIP | C3/1280-1328 | CCACAACATCAGGAAGGTAATGGGGATTGGCTGTAATGTCGTCCAAAT |

| TYLCV-BIP | C3/1337-1390 | ATCTGAATGGAAATGATGTCGTGGTTCATTCTCTATTTCAAGATAACAGACCA |

| TYLCV-F2 | C3/1256-1276 | GGCTGTAATGTCGTCCAAAT |

| TYLCV-F1c | C3/1305-1328 | CCACAACATCAGGAAGGTAATGG |

| TYLCV-B2 | C3/1385-1408 | CTCTATTTCAAGATAACAGACCA |

| TYLCV-B1c | C3/1337-1361 | ATCTGAATGGAAATGATGTCGTGG |

| ToMoTV-A-F3 | AV1/563-582 | CCACACGAACAGCGTCATG |

| ToMoTV-A-B3 | AV1/757-775 | GTCGAACCAGAGCCTGCT |

| ToMoTV-A-FIP | AV1/619-666 | ACTGGGCTCGTTGTCGTACATGTTGAACTTGGCTAGTACGAGACCGG |

| ToMoTV-A-BIP | AV1/666-707 | ACTGCCACTGTGAAGAACGACCTCCGGGCATACTGACCACC |

| ToMoTV-A-F2 | AV1/584-603 | TTGGCTAGTACGAGACCGG |

| ToMoTV-A-F1c | AV1/644-666 | ACTGGGCTCGTTGTCGTACATG |

| ToMoTV-A-B2 | AV1/728-748 | CATACTGACCACCAGTCACC |

| ToMoTV-A-B1c | AV1/666-688 | ACTGCCACTGTGAAGAACGACC |

| ToMoTV-B-F3 | NSP/413-434 | TTTTCATATGACTAACCGACG |

| ToMoTV-B-B3 | NSP/600-621 | GCTGATAAACGTTGAGATAGC |

| ToMoTV-B-FIP | NSP/451-505 | CTCCTCGACGTTTTCCATCATGTCGTTTATCTCGTTATTCTATGTTTAACCGTA |

| ToMoTV-B-BIP | NSP/521-566 | CACTGATGAGCCCAAGATGACAGCCCATGAATTATGGGCCAGGAC |

| ToMoTV-B-F2 | NSP/441-466 | TCTCGTTATTCTATGTTTAACCGTA |

| ToMoTV-B-F1c | NSP/482-505 | CTCCTCGACGTTTTCCATCATGT |

| ToMoTV-B-B2 | NSP/582-600 | TGAATTATGGGCCAGGAC |

| ToMoTV-B-B1c | NSP/521-542 | CACTGATGAGCCCAAGATGAC |

| TLV-F3 | C1/1700-1719 | AGCACGATTGAAGGGATAC |

| TLV-B3 | C1/1873-1892 | CAGTGGACATCTGGACTTC |

| TLV-FIP | C1/1747-1794 | GGAAAGAACTTCTGGGGGCCCAGAAGCTCCTTTAATTTGAACTGGCT |

| TLV-BIP | C1/1794-1845 | AGTGCTTTAGCTTTAGATAGTGCGGTGCGACTCGAGTCTATTCGAACGAAG |

| TLV-F2 | C1/1719-1740 | CTCCTTTAATTTGAACTGGCT |

| TLV-F1c | C1/1774-1794 | GGAAAGAACTTCTGGGGGCC |

| TLV-B2 | C1/1848-1869 | CTCGAGTCTATTCGAACGAAG |

| TLV-B1c | C1/1794-1818 | AGTGCTTTAGCTTTAGATAGTGCG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Otaño, Y.; Calderón-Pérez, B.; Pérez Castillo, R.; Xoconostle-Cázares, B.; Fuentes Martínez, A. Rapid LAMP-Based Detection of Mixed Begomovirus Infections in Field-Grown Tomato Plants. Viruses 2026, 18, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010019

Ruiz-Otaño Y, Calderón-Pérez B, Pérez Castillo R, Xoconostle-Cázares B, Fuentes Martínez A. Rapid LAMP-Based Detection of Mixed Begomovirus Infections in Field-Grown Tomato Plants. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Otaño, Yoslaine, Berenice Calderón-Pérez, Rosabel Pérez Castillo, Beatriz Xoconostle-Cázares, and Alejandro Fuentes Martínez. 2026. "Rapid LAMP-Based Detection of Mixed Begomovirus Infections in Field-Grown Tomato Plants" Viruses 18, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010019

APA StyleRuiz-Otaño, Y., Calderón-Pérez, B., Pérez Castillo, R., Xoconostle-Cázares, B., & Fuentes Martínez, A. (2026). Rapid LAMP-Based Detection of Mixed Begomovirus Infections in Field-Grown Tomato Plants. Viruses, 18(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010019