Kaposi Sarcoma: Retrospective Clinical Analysis with a Focus on Age and HIV Serostatus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Committee Approval

2.2. Patient Cohort

2.3. HIV ECLIA

2.4. HIV Immunochromatographic Assay

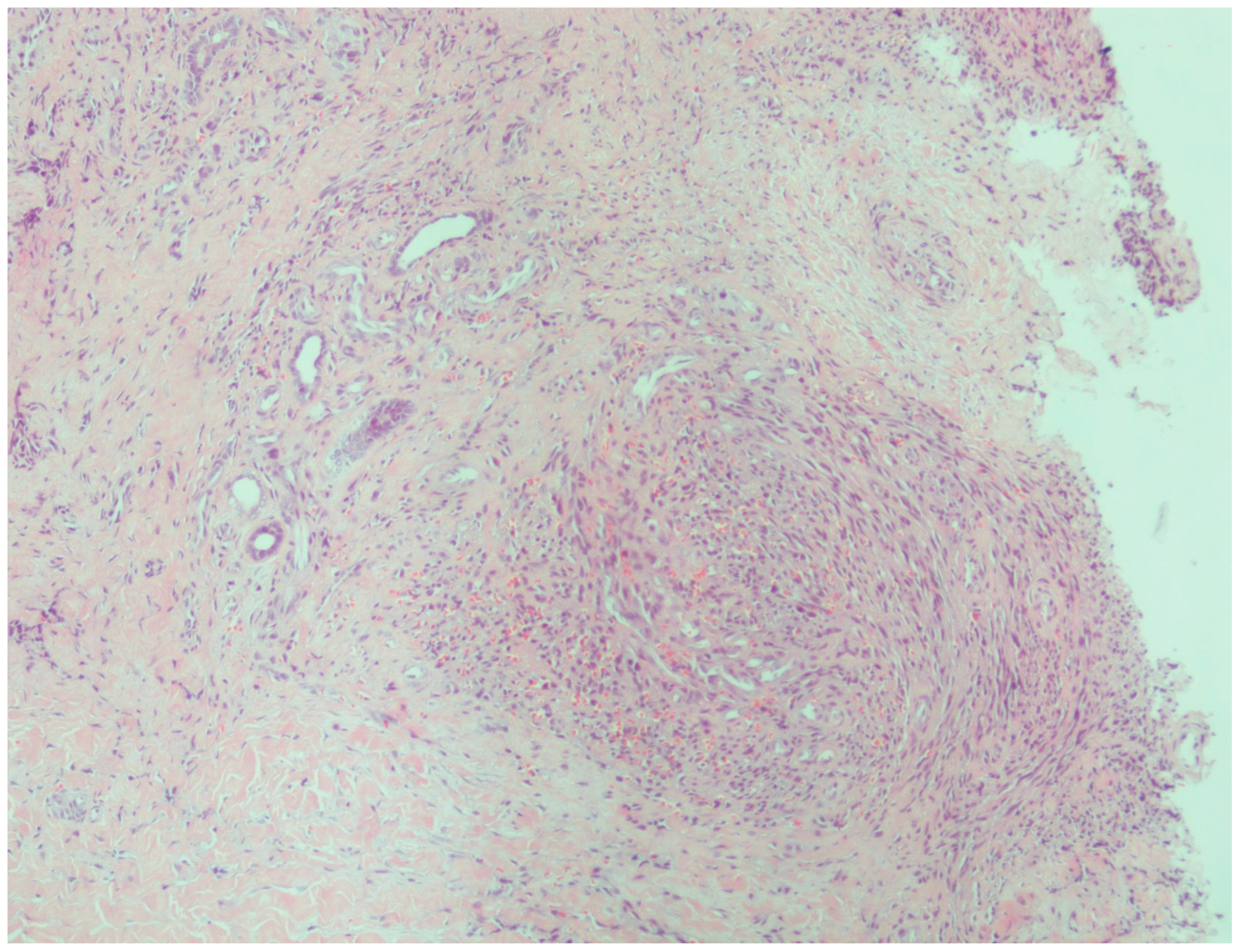

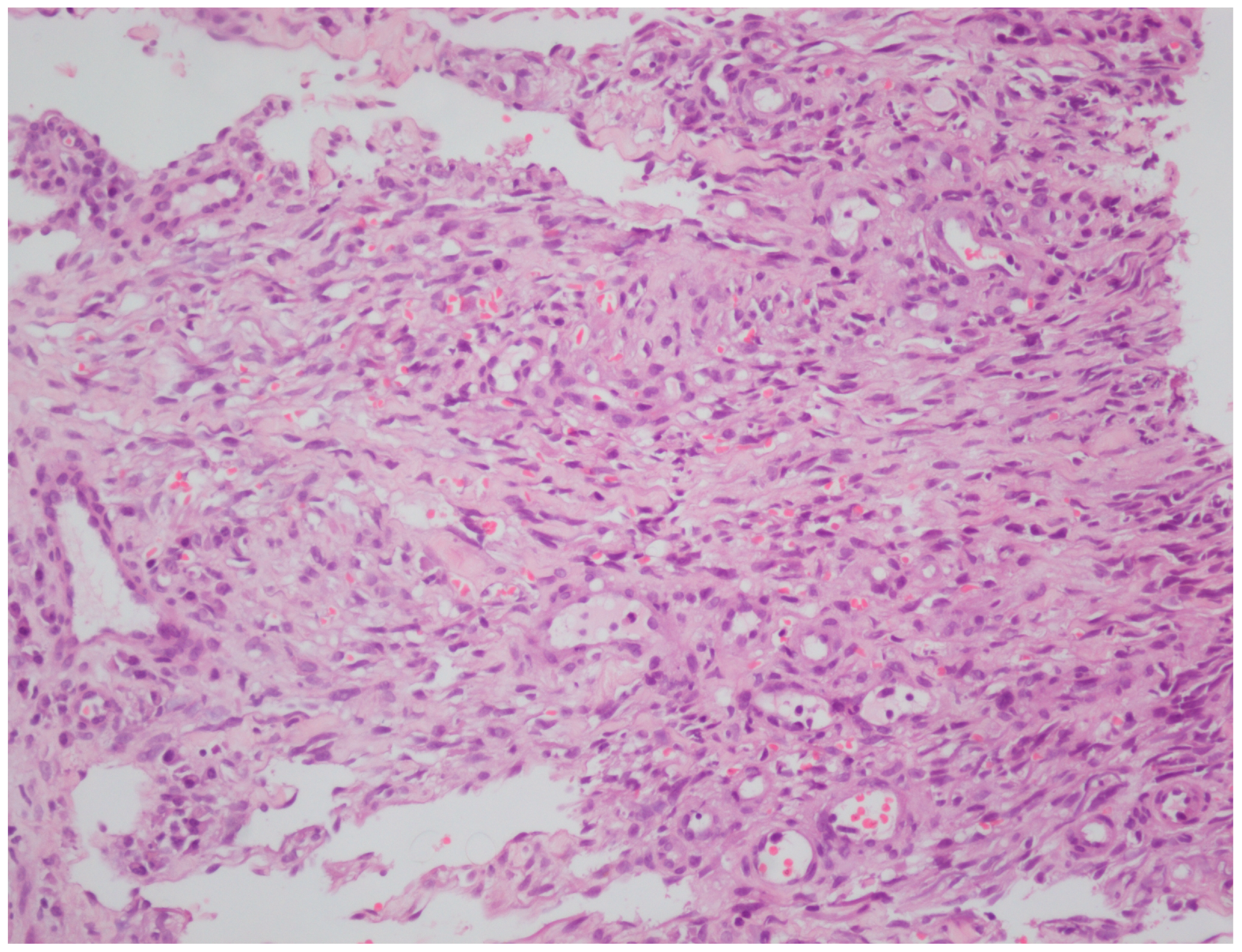

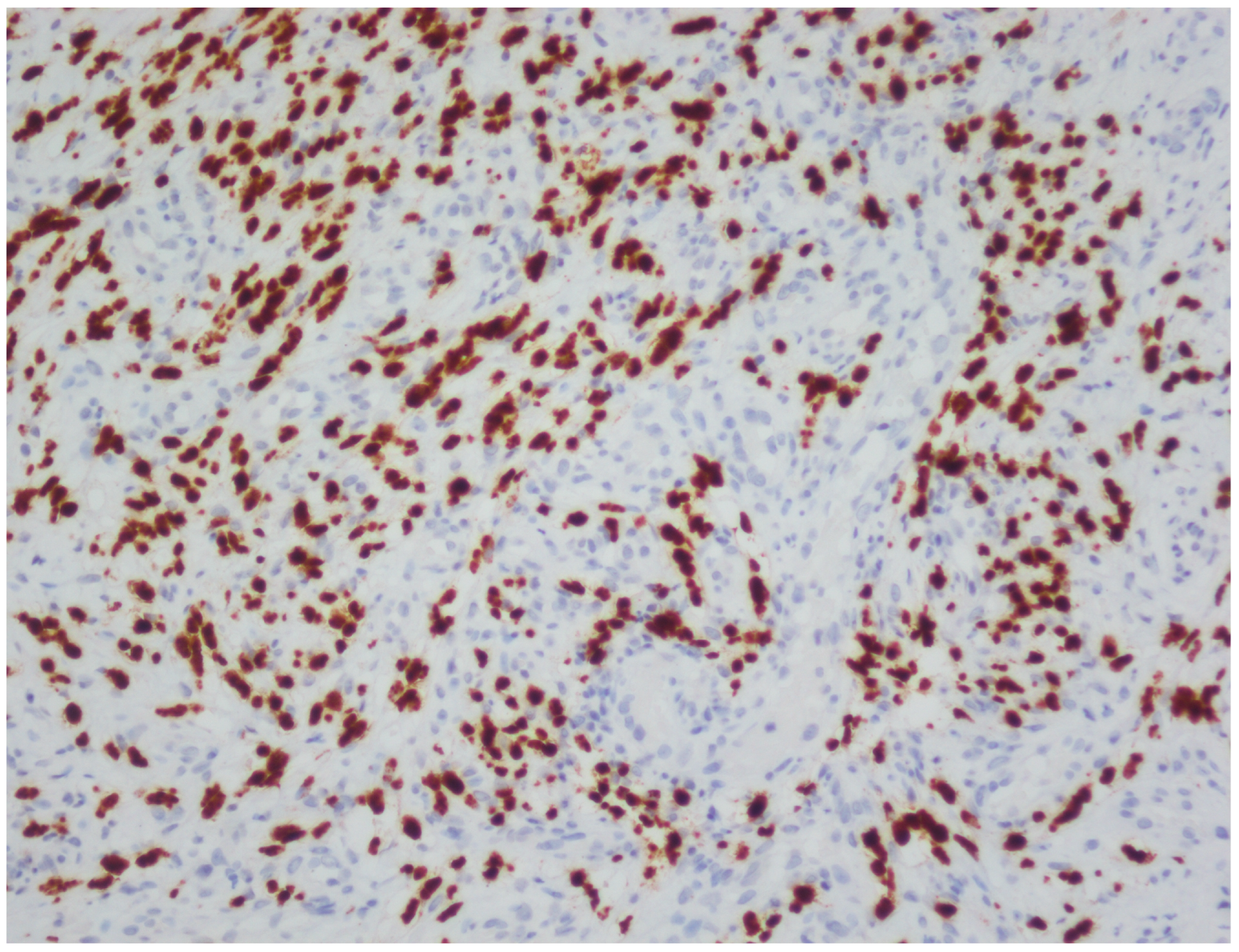

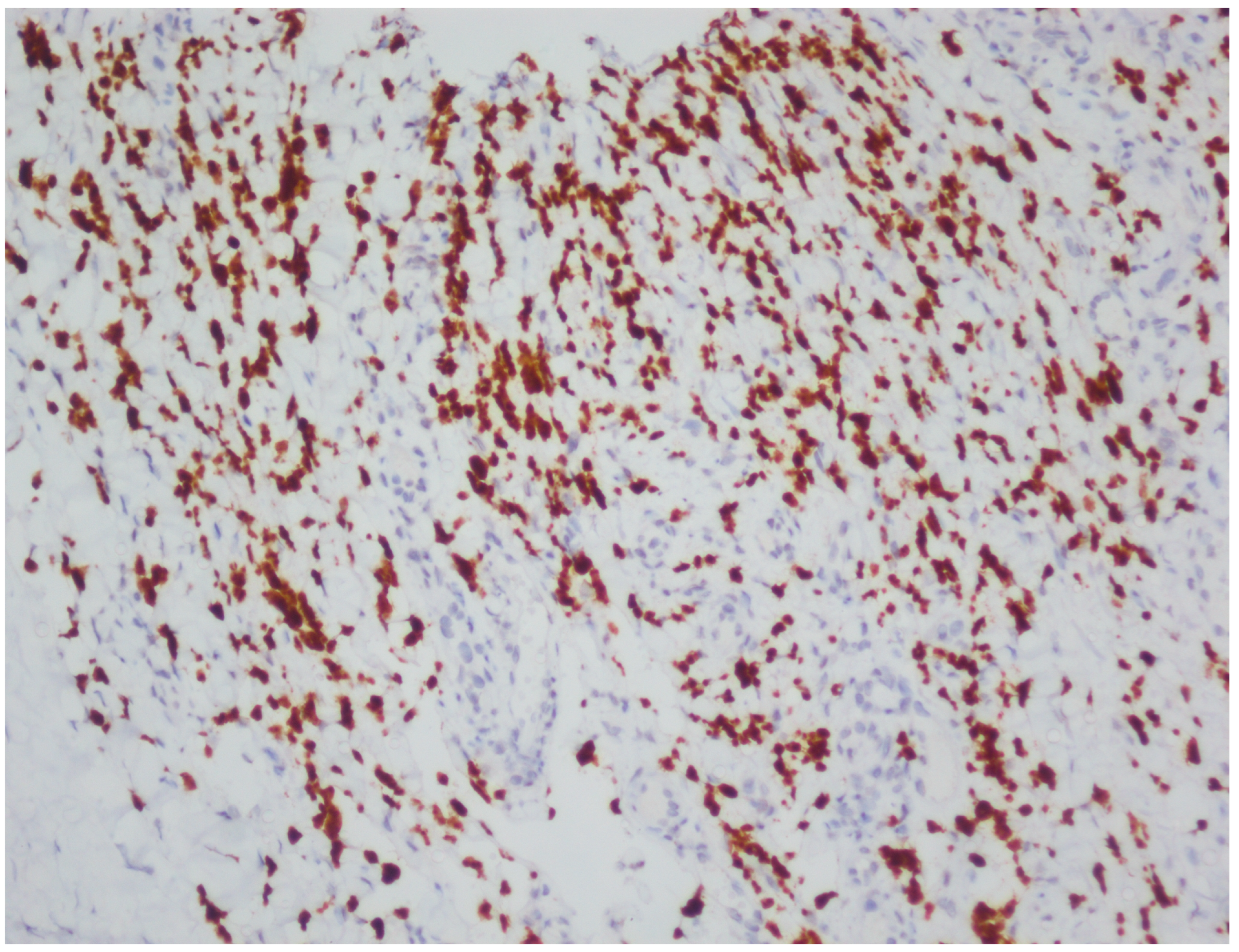

2.5. Histopathological Processing and Immunohistochemistry

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HHV-8 | Human herpesvirus 8 |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| Nd-YAG | Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| ECLIA | Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| LANA | Latency-associated nuclear antigen |

| Anti-GBM | Anti-glomerular basement membrane |

| Ab | Antibody |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| DAB | 3,3′-diaminobenzidine |

References

- Tsai, K.Y. Kaposi Sarcoma. In Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology, 10th ed.; Griffiths, C., Barker, J., Bleiker, T., Hussain, W., Simpson, R., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2024; Volume 4, pp. 138.1–138.6. [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi, E.; Tinunin, L.; Grassi, T.; Maio, V.; Grandi, V. Bullous Kaposi Sarcoma: An Uncommon Blistering Variant in an HIV-Negative Patient. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krygier, J.; Sass, U.; Meiers, I.; Marneffe, A.; de Vicq de Cumptich, M.; Richert, B. Kaposi Sarcoma of the Nail Unit: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Skin. Appendage Disord. 2023, 9, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, S.; Schöfer, H.; Hoffmann, C.; Claßen, J.; Kreuter, A.; Leiter, U.; Oette, M.; Becker, J.C.; Ziemer, M.; Mosthaf, F.; et al. S1 Guidelines for the Kaposi Sarcoma. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2022, 20, 892–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoval, J.; Bonfill-Ortí, M.; Martínez-Molina, L.; Valentí-Medina, F.; Penín, R.M.; Servitje, O. Evolution of Kaposi sarcoma in the past 30 years in a tertiary hospital of the European Mediterranean basin. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 44, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.; Lee, C.S. The emerging role of the human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) in human neoplasia. Pathology 2001, 33, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; He, F.; Jielili, A.; Zhang, Z.R.; Cui, Z.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Guo, H.T. A retrospective study of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Hotan region of Xinjiang, China. Medicine 2023, 102, e35552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.; Lee, C.S. Kaposi’s sarcoma: Clinico-pathological analysis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and non-HIV associated cases. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2002, 8, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Tian, T.; Wang, B.; Lu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Y.F.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Zou, H. Global patterns and trends in Kaposi sarcoma incidence: A population-based study. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1566–e1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, N.; Blomqvist, C.; Kivelä, P. Kaposi sarcoma in Southern Finland (2006–2018). Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 1258–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalya, P.L.; Mbunda, F.; Rambau, P.F.; Jaka, H.; Masalu, N.; Mirambo, M.; Mushi, M.F.; Kalluvya, S.E. Kaposi’s sarcoma: A 10-year experience with 248 patients at a single tertiary care hospital in Tanzania. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magri, F.; Giordano, S.; Latini, A.; Muscianese, M. New-onset cutaneous kaposi’s sarcoma following SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3747–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardini, G.; Odolini, S.; Moioli, G.; Papalia, D.A.; Ferrari, V.; Matteelli, A.; Caligaris, S. Disseminated Kaposi sarcoma following COVID-19 in a 61-year-old Albanian immunocompetent man: A case report and review of the literature. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2021, 26, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, B.; Burningham, K.; Alkul, M.; Tyring, S. Treatment of Kaposi sarcoma with intralesional cidofovir in an HIV-negative man. JAAD Case Rep. 2023, 42, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, A.A.; Efendiev, K.T.; Kornev, D.O.; Samoylova, S.I.; Fatyanova, A.S.; Karpova, R.V.; Reshetov, I.V.; Loschenov, V.B. Photodynamic therapy of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with video-fluorescence control. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasca, M.R.; Luppino, I.; Spurio Catena, A.; Micali, G. Nodular Classic Kaposi’s Sarcoma Treated With Neodymium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Laser Delivered Through a Tilted Angle: Outcome and 12-Month Follow Up. Lasers Surg. Med. 2020, 52, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancredi, V.; Licata, G.; Buononato, D.; Boccellino, M.P.; Argenziano, G.; Giorgio, C.M. Topical Sirolimus 0.1% as Off-Label Treatment of Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, C.M.R.; Licata, G.; Briatico, G.; Babino, G.; Fulgione, E.; Gambardella, A.; Alfano, R.; Argenziano, G. Comparison between propranolol 2% cream versus timolol 0.5% gel for the treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genedy, R.M.; Owais, M.; El Sayed, N.M. Propranolol: A Promising Therapeutic Avenue for Classic Kaposi Sarcoma. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2025, 15, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daadaa, N.; Souissi, A.; Chaabani, M.; Chelly, I.; Ben Salem, M.; Mokni, M. Involution of classic Kaposi sarcoma lesions under acitretin treatment Kaposi sarcoma treated with acitretin. Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 8, 3340–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.; Yu, Y.; Su, Z.; Lu, Y. Rapid improvements in Kaposi sarcoma with metformin: A report of two cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 2025, 193, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettuzzi, T.; Lebbe, C.; Grolleau, C. Modern Approach to Manage Patients With Kaposi Sarcoma. J. Med. Virol. 2025, 97, e70294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavak, E.E.; Ürün, Y. Classical Kaposi sarcoma: An insight into demographic characteristics and survival outcomes. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, D.; Srinivasan, S.; Paul, P.M.; Ko, N.; Garlapati, S. A Retrospective Study on the Incidence of Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States From 1999 to 2020 Using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research (CDC WONDER) Database. Cureus 2025, 17, e77213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, S.; Zorlu, O.; Bulbul Baskan, E.; Balaban Adim, S.; Aydogan, K.; Saricaoglu, H. Retrospective Analysis of 91 Kaposi’s Sarcoma Cases: A Single-Center Experience and Review of the Literature. Dermatology 2018, 234, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.Y.; Lin, C.L.; Chen, G.S.; Hu, S.C. Clinical features of Kaposi’s sarcoma: Experience from a Taiwanese medical center. Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabar, S.; Costagliola, D. Epidemiology of Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tounouga, D.N.; Kouotou, E.A.; Nansseu, J.R.; Zoung-Kanyi Bissek, A.C. Epidemiological and Clinical Patterns of Kaposi Sarcoma: A 16-Year Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study from Yaoundé, Cameroon. Dermatology 2018, 234, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The China PEACE Collaborative Group. Association of age and blood pressure among 3.3 million adults: Insights from China PEACE million persons project. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safai, B.; Miké, V.; Giraldo, G.; Beth, E.; Good, R.A. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma with second primary malignancies: Possible etiopathogenic implications. Cancer 1980, 45, 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, L.; Genovese, G.; Tourlaki, A.; Della Bella, S. Coexistence of Kaposi’s sarcoma and psoriasis: Is there a hidden relationship? Eur. J. Dermatol. 2018, 28, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.J.; Yang, Y.H.; Chen, P.C.; Chen, L.W.; Wang, S.S.; Shih, Y.J.; Chen, L.Y.; Chen, C.J.; Hung, C.H.; Lin, C.L. Diabetes and risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma: Effects of high glucose on reactivation and infection of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 80595–80611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugcu, M.; Kasapoglu, U.; Ruhi, C.; Sayman, E. Kaposi Sarcoma in a Chronic Renal Failure Patient Treated by Hemodialysis. Turk. Neph. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 25, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Chun, J.S.; Hong, S.K.; Kang, M.S.; Seo, J.K.; Koh, J.K.; Sung, H.S. Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with chronic renal failure undergoing dialysis. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, J.A. Anergy and immunosuppression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rev. Colomb. Reumatol. 2021, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Age | Gender | Anti-HIV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECLIA | HIV-1/2 Ab Differentiation Assay | |||

| 1 | 53 | Male | Negative | |

| 2 | 82 | Male | Negative | |

| 3 | 68 | Male | Negative | |

| 4 | 67 | Female | Negative | |

| 5 | 81 | Female | Negative | |

| 6 | 65 | Female | Negative | |

| 7 | 50 | Male | Positive | Positive |

| 8 | 75 | Male | Negative | |

| 9 | 84 | Male | Negative | |

| 10 | 30 | Male | Positive | Positive |

| 11 | 45 | Male | Positive | Positive |

| 12 | 78 | Male | Negative | |

| 13 | 54 | Male | Positive | Positive |

| 14 | 99 | Female | Negative | |

| 15 | 71 | Male | Negative | |

| 16 | 81 | Female | Negative | |

| 17 | 72 | Male | Negative | |

| 18 | 69 | Male | Negative | |

| 19 | 70 | Male | Negative | |

| 20 | 73 | Female | Negative | |

| 21 | 79 | Male | Negative | |

| 22 | 74 | Male | Negative | |

| 23 | 43 | Male | Negative | |

| 24 | 81 | Male | Negative | |

| 25 | 28 | Male | Positive | Positive |

| 26 | 77 | Male | Negative | |

| 27 | 54 | Male | Positive | Positive |

| 28 | 72 | Female | Negative | |

| 29 | 53 | Male | Negative | |

| 30 | 82 | Female | Negative | |

| 31 | 64 | Female | Negative | |

| 32 | 80 | Male | Negative | |

| 33 | 77 | Male | Negative | |

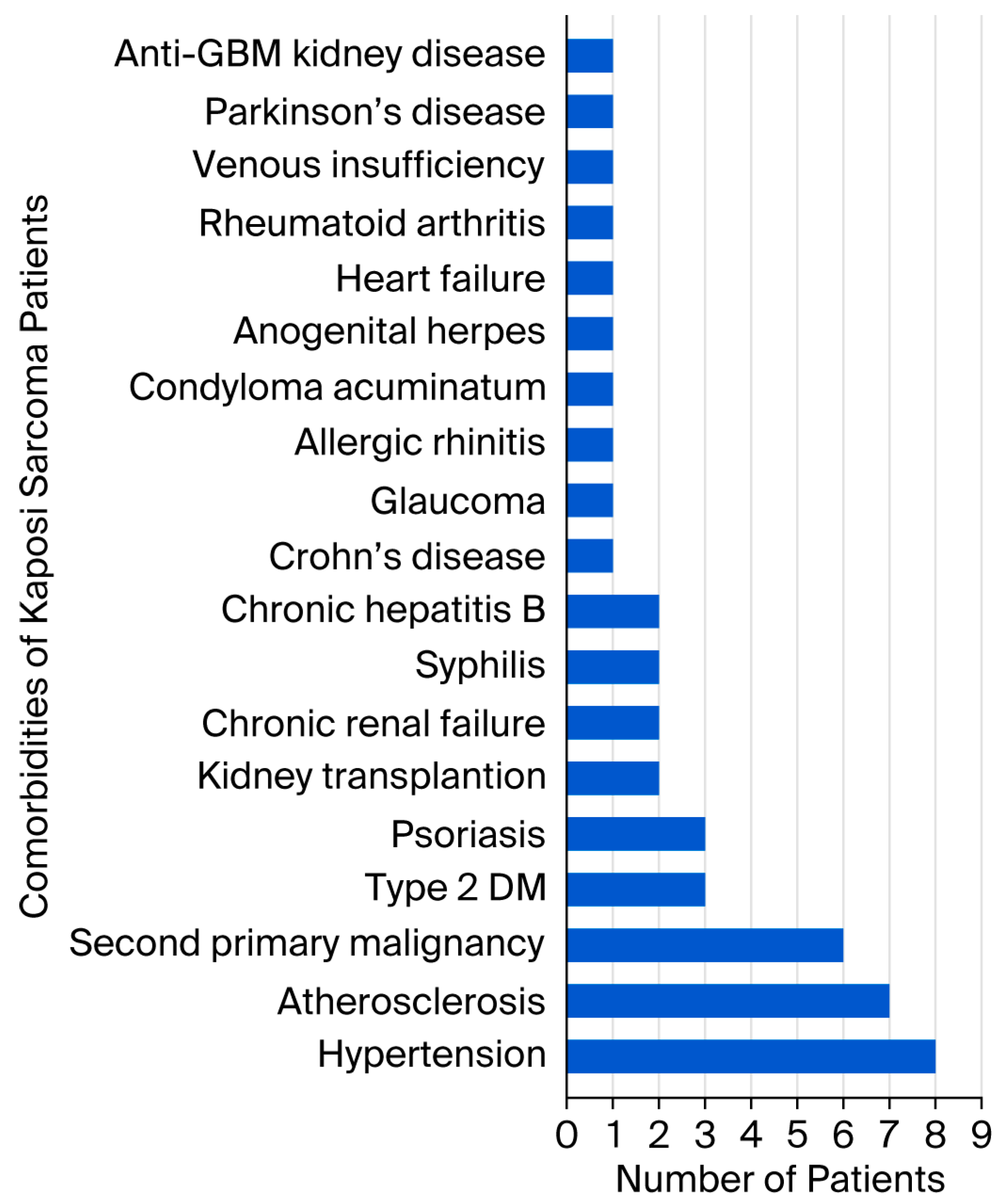

| Case | Age | Gender | Localization | Anti-HIV | Comorbidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | Male | Bilateral cruris and feet | Negative | Kidney transplant recipient |

| 2 | 82 | Male | Bilateral wrists and feet | Negative | Hypertension, atherosclerosis |

| 3 | 68 | Male | Left hand, right foot | Negative | Hypertension, chronic renal failure, Crohn’s disease |

| 4 | 67 | Female | Left arm, left hand, right foot | Negative | None |

| 5 | 81 | Female | Right ankle | Negative | Hypertension, glaucoma, chronic peripheral venous insufficiency |

| 6 | 65 | Female | Left foot | Negative | Allergic rhinitis |

| 7 | 50 | Male | Right axilla and chest | Positive | Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), condyloma acuminatum, anogenital herpes |

| 8 | 75 | Male | Right cruris | Negative | Type 2 diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, renal cell carcinoma |

| 9 | 84 | Male | Right foot | Negative | Hypertension, atherosclerosis |

| 10 | 30 | Male | Extensive skin lesions | Positive | None |

| 11 | 45 | Male | Extensive skin lesions | Positive | None |

| 12 | 78 | Male | Left ankle | Negative | Psoriasis |

| 13 | 54 | Male | Extensive skin lesions | Positive | Syphilis |

| 14 | 99 | Female | Bilateral cruris | Negative | Hypertension, atherosclerosis |

| 15 | 71 | Male | Left hand, left foot | Negative | Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, type 2 DM, atherosclerosis, chronic hepatitis B |

| 16 | 81 | Female | Right knee | Negative | Atherosclerosis |

| 17 | 72 | Male | Left elbow | Negative | Psoriasis |

| 18 | 69 | Male | Left arm, bilateral feet | Negative | Thyroid papillary carcinoma, glioblastoma |

| 19 | 70 | Male | Left knee, left labial commissure | Negative | None |

| 20 | 73 | Female | Right arm, right foot | Negative | Hypertension |

| 21 | 79 | Male | Bilateral cruris | Negative | Basal cell carcinoma |

| 22 | 74 | Male | Right thigh | Negative | Prostate carcinoma |

| 23 | 43 | Male | Bilateral cruris | Negative | Kidney transplant recipient |

| 24 | 81 | Male | Right ankle | Negative | Psoriasis |

| 25 | 28 | Male | Left arm, left cruris, trunk | Positive | None |

| 26 | 77 | Male | Bilateral arms and legs | Negative | Parkinson’s disease, hypertension, prostate carcinoma |

| 27 | 54 | Male | Left cruris, left ankle | Positive | Syphilis |

| 28 | 72 | Female | Right foot | Negative | None |

| 29 | 53 | Male | Bilateral feet, gastric antrum and corpus | Negative | Anti-glomerular basement membrane kidney disease |

| 30 | 82 | Female | Left cruris | Negative | Chronic hepatitis B, rheumatoid arthritis |

| 31 | 64 | Female | Left arm | Negative | None |

| 32 | 80 | Male | Right foot | Negative | None |

| 33 | 77 | Male | Right ankle | Negative | Hypertension, atherosclerosis, chronic renal failure, heart failure |

| Anti-HIV | p * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative, n (%) | Positive, n (%) | ||

| Lower extremities | 25 (92.6) | 2 (33.3) | 0.005 |

| Upper extremities | 9 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0.640 |

| Trunk | 0 (0.0) | 2 (33.3) | 0.028 |

| Head | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| Diffuse skin involvement | 0 (0.0) | 3 (50.0) | 0.004 |

| Gastrointestinal system | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

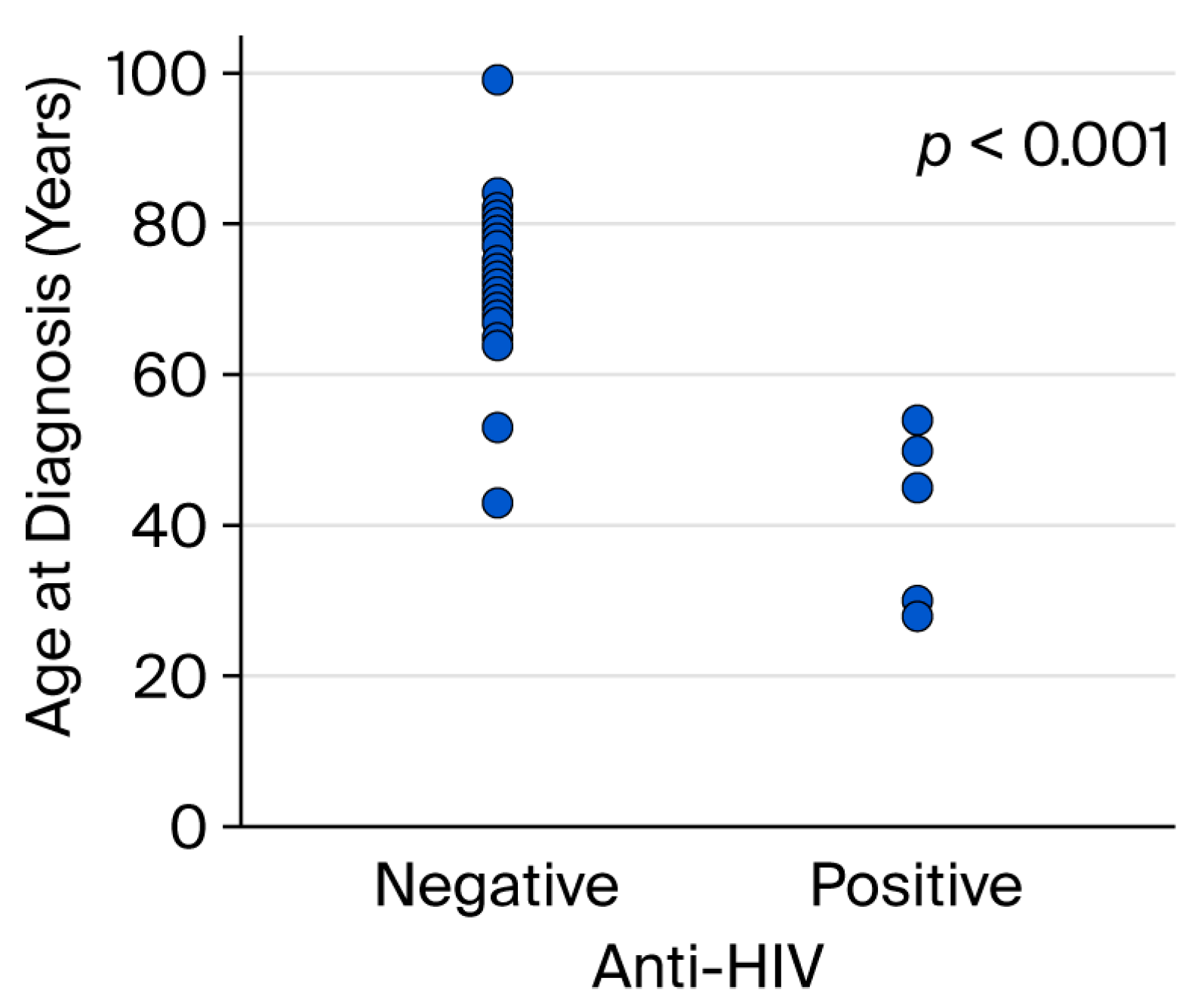

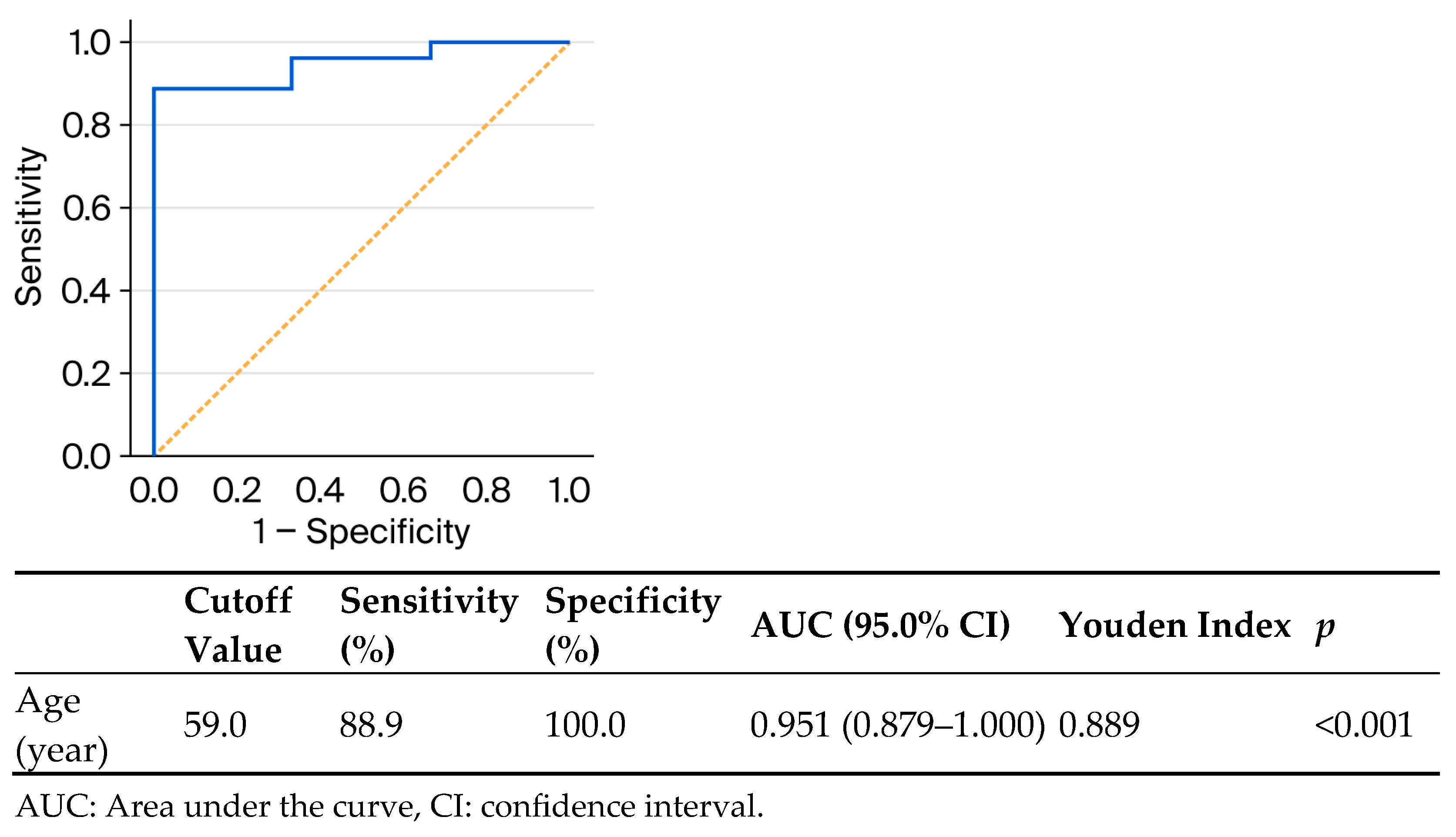

| Anti-HIV | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||

| Age (year), mean ± standard deviation | 73.0 ± 11.2 | 43.5 ± 11.7 | <0.001 a | |

| Age (year), n (%) | ≤59 | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | <0.001 b |

| ≥60 | 24 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Erçin, Z.; Toprak, M. Kaposi Sarcoma: Retrospective Clinical Analysis with a Focus on Age and HIV Serostatus. Viruses 2026, 18, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010144

Erçin Z, Toprak M. Kaposi Sarcoma: Retrospective Clinical Analysis with a Focus on Age and HIV Serostatus. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010144

Chicago/Turabian StyleErçin, Zuhal, and Mehtap Toprak. 2026. "Kaposi Sarcoma: Retrospective Clinical Analysis with a Focus on Age and HIV Serostatus" Viruses 18, no. 1: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010144

APA StyleErçin, Z., & Toprak, M. (2026). Kaposi Sarcoma: Retrospective Clinical Analysis with a Focus on Age and HIV Serostatus. Viruses, 18(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010144