Abstract

RNA granules, aggresomes, and autophagy are key players in the immune response to viral infections. They provide countermeasures that regulate translation and proteostasis in order to rewire cell signaling, prevent viral interference, and maintain cellular homeostasis. The formation of cellular aggregates and inclusions is one of the strategies to minimize viral infections and virus-induced cell damage and to promote cellular survival. However, viruses have developed several strategies to interfere with these cellular processes in order to achieve productive replication within the host cells. A review on how these mechanisms could function as modulators of cell signaling and antiviral factors will be instrumental in refining the current scientific knowledge and proposing means whereby cellular granules and aggregates could be induced or prevented to enhance the antiviral immune response in mammalian cells.

1. Introduction

Viruses lack their own metabolic machinery, therefore, to establish viral replicative complexes and achieve a robust and productive replication, they rely on essential cellular processes. Although some viruses can cause no apparent change in the infected cell, in most cases they can cause a wide range of structural, functional, and biochemical changes within the host cell [1]. As a countermeasure to these virus-induced cellular changes, host cells use structural, molecular, and or genetic mechanisms to control viral replication and spread by stimulating the formation of cellular inclusions like stress granules (SGs) and processing bodies (P-bodies). These cellular structures and their components serve as cytoprotective and survival factors that trigger intracellular RNA transcription and translation arrest or sequestrate vital cellular components required for viral replication. Alternatively, virus-infected cells can trigger membrane and cytoskeleton remodeling, which results in the formation of insoluble cytoplasmic aggregates, such as aggresomes, and autophagy [2]. Essential cellular and viral proteins required for effective viral replication, virus-induced stress proteins, and viral or cellular toxic proteins are sequestered and or degraded in these aggregates. Synergistically, aggresome and SG may be cleared by the cellular degradation machinery and autophagy to facilitate viral clearance and cellular recovery [2,3].

In light of recent knowledge, this review discusses the cytoprotective functions of cellular inclusions, aggregates, and their components, providing an overview on how these structures can function as an antiviral mechanism and a cellular signaling regulatory mechanism in virus-infected cells.

5. Interplay between Virus-Induced Aggregates and Inclusions

Mammalian cells face different types of stress including virus-induced stress. In dealing with this, eukaryotic cells activate several mechanisms to regulate the effect of this stress, inhibit the stressor, and promote cell survival [80]. Intracellular aggregates and inclusions serve as stress suppressors and cellular quality control strategies to maintain cellular integrity and viability. These cellular structures share some characteristics, and their mechanism of action and activation are connected at several levels.

Infection with a wide range of DNA and RNA viruses has been reported to activate the autophagic response, as inferred from the increased number of autophagic vesicles in virus-infected cells. By cytoplasmic organelles that gather cellular contents into double-membrane vesicles, the autoghagosomes, autophagy specifically delivers aggresomes and SGs for degradation via autolysosomes. Considering the dynamic nature of autophagy, it is important to gain insight on how SGs and aggresomes coordinately communicate with autophagy to prevent viral pathogenesis and how they are subsequently cleared by it. Both mechanisms will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

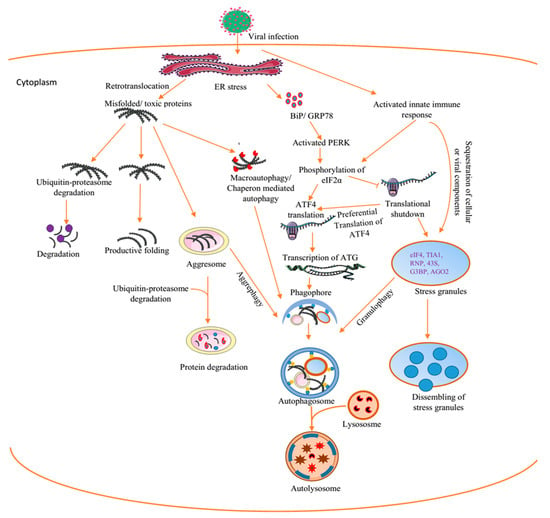

Various mechanisms have been reported that activate the autophagic response in virus-infected cells. Virus-induced autophagy can be triggered, for instance, when a virus binds to a receptor on the host cell. An example is CD46 surface receptor for measles virus and adenovirus [62,81]. Besides attachment, HCV, coxsackievirus B (CVB), and some nucleocytoplasmic DNA viruses—hepatitis B virus (HBV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV)—induce autophagy inside the host cells by activating stress responses like ROS or ER stress [77]. Stress to the ER disrupts the global protein production and folding. Misfolded proteins are aggresome-prone. To restore ER protein homeostasis, misfolded or unfolded proteins are retrotranslocated from the ER to the cytosol [82] for subsequent degradation by proteasomes and autophagy [83].

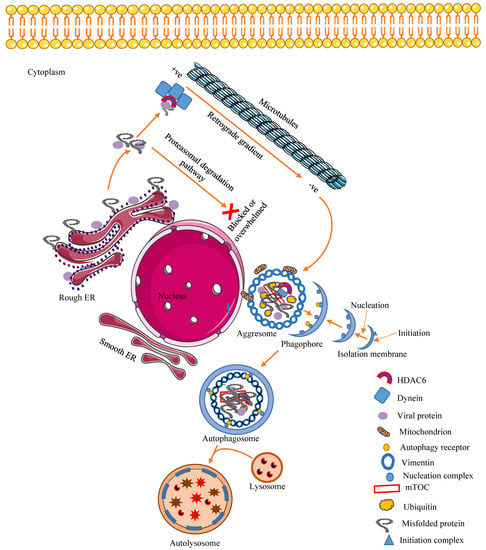

Likewise, to avert ER stress-induced cell death, the cells activate UPR, PKR-like ER (PKR), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and inositol-requiring protein 1α (IRE1α) [84]. Activated PERK mediates the phosphorylation of eIF2α. Phosphorylated eIF2α supresses cellular translation and prevents the formation of eIF2–guanosine triphosphate–initiator methionyl-transferRNA (eIF2–GTP–met-tRNAi) [85,86]. Classically, the formation of SGs is triggered at this step. Although the phosphorylation of eIF2α causes a temporal global translational shutdown, there is a preferential translation of activation transcription factor 4 (ATF4) [87]. The eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway fine-tunes the upregulation of ATG, essential for stress-induced autophagy [87]. The activation of PERK connects SG to autophagy [87,88] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interplay between virus-induced cellular aggregates and inclusions. The replication of viruses triggers ER stress. This causes the release of BiP/GRP79 into the cytoplasm and the subsequent activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). This could ultimately lead to the clearance of toxic proteins by autophagy. Alternatively, virus infection directly activates innate immune responses capable of causing translational shutdown and stress granules (SGs) formation. Cellular and or viral proteins could appear as misfolded or toxic proteins and are recruited to the chaperon pathway for productive refolding and/or to the proteasomal pathway. However, when these pathways are blocked, the misfolded proteins are sequestrated in the aggresomes and are cleared by autophagy–aggrephagy. BiP/GRP78, binding immunoglobulin protein/glucose-regulated protein 78, ATF4, activating transcription factor 4, eIF2α, eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha, ATG, autophagy-related protein, RNP, ribronucleoprotein, AGO2aArgonaute, G3BP-1, Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein-1, PERK, protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase. Figure was drawn on smart.servier.com.

Since SGs and aggresomes are space-filling entities, if they exceed a certain threshold, they could physically interrupt normal cellular functions. Hence, to prevent this, aggresomes and SGs components dissassemble in multiple steps that involve the production of smaller fragments that are cleared by chaperon-dependent degradation or autophagy [16]. Alternatively, SGs and aggresomes can be targeted, via autophagy receptors [89], for selective autophagic clearance, termed granulophagy and aggrephagy, respectively [90]. Autophagy receptors like SQTM1/p62 and calcium-binding, coiled-coil domain-containing protein 2/nuclear dot 10 protein 52 (CALCOCO2/NDP52) have been reported to mediate selective autophagy during viral pathogenesis [91]. For instance, in Coxsackievirus A (CVA)-infected cells, granulophagy is mediated by the interaction between the ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain of p62 and the ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD) of HDAC6, a component of viral RNA-induced SGs [92]. Selective autophagy double-membrane vesicles, the autophagosomes, encapsulate and deliver their cargo to lysosomes for degradation.

Several factors appear to specifically target SGs for autophagic degradation. Aside from canonical ATG, granulophagy requires valosin-containing protein, an ATPase that degrades SG components in autophagy [16,90]. Other factors are the return of the sequestrated mRNA to active translation and the decapping of SG mRNA [16,93].

Some viruses and viral proteins share structural motifs that are similar to amino acid cargo recognized by dynein; this suggests that they are aggresome-prone and susceptible to degradation by autophagy. A recent study by Mohamud et al. (2019) showed that the autophagy receptors CALCOCO2 and p62 regulate CVB3 pathogenesis through the interaction with CVB3 viral protein 1 (VP1) that undergoes ubiquitination during infection. Further investigation revealed that both receptors appear to have a role in virophagy through interaction with VP1. Knockdown of p62 resulted in elevated viral titers [94]. Specifically, ubiquitylated proteins may have a role in targeting the selective autophagy of aggresomes and SGs [95].

6. Virus Exploitation of Cellular Inclusions and Aggregates

A striking observation is that the formation of aggresomes and SGs and autophagy not only inhibit viral pathogenesis but also are employed by viruses to subvert host proteins involved in antiviral signaling. Viruses employ different mechanisms to manipulate and co-opt these cellular structures and their components for effective replication. For instance, active viral replication is not commonly associated with the presence of SGs [2]. Therefore, in order to survive, viruses have to develop mechanisms to evade or prevent the formation of RNA granules. Viral evasion mechanisms include prevention of the assembling of RNA granules and dissolution of existing ones [16]. Alternatively, viruses can subvert SG antiviral proteins. This can compromise granular integrity and antiviral efficiency. For example HSV, dengue virus, and HIV-1 viral proteins block SG formation by binding to the SG core proteins T-cell intracellular antigen (TAI-1) and G3BP1 [96,97]. Likewise, HIV-1 vif interacts with APOBEC3, a component of SGs, to cause its proteasomal degradation. This viral protein subverts the antiviral activity of APOBEC3 in HIV-infected cells to promote viral pathogenesis [48]. Equally, RISC-mediated antiviral activity of P-bodies is strongly inhibited by HIV-1 vif, which is capable of disrupting P-body structural integrity by allowing the virus to replicate virtually undisturbed [98].

Other viruses can cause the dispersion of existing RNA granules structural components [14]. An experimental report by Dougherty et al. (2015) demonstrated that poliovirus induces SG formation during the early phase of infection while at mid phase, it inhibits SG formation and disperses P-body components. Inhibition of SG formation during poliovirus infection has been linked to cleavage of G3BP1 in SGs by the viral protein 3Cpro [99].

Evidence suggests that the assembly of several cytoplasmic viruses in mammalian cells occurs at an intracellular site called the ‘virus factory’ or ‘viroplasm’ [2]. The virus factory contains cellular and viral proteins required for viral genomic replication and morphogenesis of new virions. In some instances, the viroplasm has been compared to the cellular aggresome. The replication and assembly of poxvirus have been demonstrated to take place in a virus factory that resembles the aggresome [2,24,100]. Some virus factories contain similar components found in aggresomes, such as chaperon/ heat shock protein, proteases, and MTOC [2]. An MTOC-dependent virus factory has been observed in togavirus-, flavivirus-, and buyanvirus-infected cells [2]. Virus factories are sometimes functionally comparable to cellular aggresomes. This highlight the possibility that aggresomes can be used as virus replicative and assembly sites [2,24].

Experimental reports suggested that some viruses can induce the accumulation of cellular antiviral proteins and subsequently facilitate their degradation by selective autophagy (aggrephagy). Murid cytomegalovirus (MCMV)—a herpesvirus—M45 protein induces the sequestration of two cellular signaling proteins, NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) and receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), through its ‘induced protein aggregation motif’ (a conserved protein motif whose homologous is present in several human herpesviruses) and subsequently facilitates their degradation by autophagy to evade the host immune response in infected cells [101].

Autophagy, a cellular process aimed to clear pathogens [102], can be subverted during virus replication. Mechanisms of viral evasion of autophagy include exploitation of secretory autophagy to exit the cells, non-lytic shedding, and blockage of the autophagic flux. For instance, a report by Granato et al. (2014) showed that EBV, a gammaherpes virus associated with non-Hodgkin’s B cell lymphoma, blocks the autophagic flux at the final step during reactivation from latency [102]. A similar report by Kembal et al. (2010) showed an increase in the number of large autophagy-like double-membraned vesicles, megaphagosomes, and the accumulation of the autophagy receptor p63 in CVB3-infected cells. This suggests that CVB3 blocks a later stage in autophagy formation [103]. The double-membraned vesicles megaphagosomes serve as a scaffolding for viral RNA replication and immune escape [104,105]. Likewise, viruses can subvert autophagic responses by targeting one of the autophagy proteins. This phenomenon has been reported in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)-infected cells. KSHV is a human herpes virus associated with multiple cancers, whose oncogenic protein v-cyclin interacts with ATG3 to subvert autophagic responses, blocks senescence, and enhances viral replication [106]. However, unlike other viruses that block autophagy, some viruses activate autophagy to benefit from autophagy-dependent processes. For instance, Dengue virus (DENV), a mosquito-borne single-stranded RNA virus that causes haemorrhagic fever, benefits from autophagy-specific processes like lipophagy, a form of autophagy that serves as an alternative to lipid metabolism [104]. DENV co-localizes with lipid droplets within the autolysosome, which correlates with an increase in DENV replication [107].

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This review shed light on aggresomes, SGs, and autophagy as cellular regulatory structures and antiviral mechanisms. It highlights that these virus-induced aggregates and their components could play a dual role as elements of the antiviral innate immune response and as regulators of other cellular activities. They act by sequestrating and/or degrading cellular or viral replicative components to maintain a homeostatic and antiviral state within cells. The sequestrated substances become trapped and are sorted for degradation or become unavailable for the generation of new virus particles. Alternatively, cellular aggregates, like SGs and aggresomes, serve as protective structures and storage sites, where important active cellular components and structures are sequestrated in order to prevent their rapid degradation during virus infection.

Despite our current, developing knowledge of the mechanisms and functions of virus-induced cellular aggregates and inclusions, mechanisms of interactions between these aggregates/inclusions and viruses are still to be deciphered to obtain a complete view of host–virus interactions at the cellular level. Furthermore, since accumulating evidence suggests that these structures can be subverted to enhance viral replication or can be used as viral replicative platforms, the recognition of key cellular and viral regulatory proteins that promote viral subversion of these aggregates and inclusions will provide a significant advancement for the development of new antiviral therapeutic strategies and approaches to fight viral infections.

Author Contributions

O.I.O.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, S.C., J.M. and Z.Z.; Writing-Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571999 and 81871652) to Z.Z. S.C. was supported by a grant of University Nursing Program for Young Scholars with Creative Talents in Heilongjiang Province (UNPYSCT2015029). O.I.O. and J.M. were supported by China Scholarship Council (CSC) (181FOFEEDD and 2018DFJ019502).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kaminskyy, V.; Zhivotovsky, B. To kill or be killed: How viruses interact with the cell death machinery. J. Intern. Med. 2010, 267, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshe, A.; Gorovits, R. Virus-induced aggregates in infected cells. Viruses 2012, 4, 2218–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wileman, T. Aggresomes and autophagy generate sites for virus replication. Science 2006, 312, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.G.; Loschi, M.; Desbats, M.A.; Boccaccio, G.L. RNA granules: The good, the bad and the ugly. Cell Signal. 2011, 23, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.; Kedersha, N. Stress granules: The Tao of RNA triage. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008, 33, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedersha, N.; Anderson, P. Mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods Enzymol. 2007, 431, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reineke, L.C.; Lloyd, R.E. Diversion of stress granules and P-bodies during viral infection. Virology 2013, 436, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panas, M.D.; Ivanov, P.; Anderson, P. Mechanistic insights into mammalian stress granule dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallois-Montbrun, S.; Kramer, B.; Swanson, C.M.; Byers, H.; Lynham, S.; Ward, M.; Malim, M.H. Antiviral protein APOBEC3G localizes to ribonucleoprotein complexes found in P bodies and stress granules. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 2165–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente-Echeverria, F.; Melnychuk, L.; Mouland, A.J. Viral modulation of stress granules. Virus Res. 2012, 169, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.E. How do viruses interact with stress-associated RNA granules? PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, U.; Parker, R. Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science 2003, 300, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makinen, K.; Lohmus, A.; Pollari, M. Plant RNA Regulatory Network and RNA Granules in Virus Infection. Front. Plant. Sci. 2017, 8, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W.C.; Lloyd, R.E. Cytoplasmic RNA Granules and Viral Infection. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2014, 1, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, R.W.; Parker, R. Coupling of Ribostasis and Proteostasis: Hsp70 Proteins in mRNA Metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi, H.; Stochaj, U. Cytoplasmic stress granules: Dynamic modulators of cell signaling and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblete-Duran, N.; Prades-Perez, Y.; Vera-Otarola, J.; Soto-Rifo, R.; Valiente-Echeverria, F. Who Regulates Whom? An Overview of RNA Granules and Viral Infections. Viruses 2016, 8, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckham, C.J.; Parker, R. P bodies, stress granules, and viral life cycles. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 3, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, M.; Jogi, M.; Onomoto, K. Regulation of antiviral innate immune signaling by stress-induced RNA granules. J. Biochem. 2016, 159, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomoto, K.; Jogi, M.; Yoo, J.S.; Narita, R.; Morimoto, S.; Takemura, A.; Sambhara, S.; Kawaguchi, A.; Osari, S.; Nagata, K.; et al. Critical role of an antiviral stress granule containing RIG-I and PKR in viral detection and innate immunity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bley, N.; Lederer, M.; Pfalz, B.; Reinke, C.; Fuchs, T.; Glass, M.; Moller, B.; Huttelmaier, S. Stress granules are dispensable for mRNA stabilization during cellular stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.W.; Onomoto, K.; Wakimoto, M.; Onoguchi, K.; Ishidate, F.; Fujiwara, T.; Yoneyama, M.; Kato, H.; Fujita, T. Leader-Containing Uncapped Viral Transcript Activates RIG-I in Antiviral Stress Granules. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Okabe, K.; Tani, T.; Funatsu, T. Dynamic association-dissociation and harboring of endogenous mRNAs in stress granules. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 4087–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wileman, T. Aggresomes and pericentriolar sites of virus assembly: Cellular defense or viral design? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 61, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozelle, D.K.; Filone, C.M.; Kedersha, N.; Connor, J.H. Activation of stress response pathways promotes formation of antiviral granules and restricts virus replication. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 34, 2003–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopito, R.R. Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol. 2000, 10, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwaker, D.; Mishra, K.P.; Ganju, L. Effect of modulation of unfolded protein response pathway on dengue virus infection. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2015, 47, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olzmann, J.A.; Chin, L.S. Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination: A signal for targeting misfolded proteins to the aggresome-autophagy pathway. Autophagy 2008, 4, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Statsyuk, A.V. An inhibitor of ubiquitin conjugation and aggresome formation. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 5235–5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mata, R.; Gao, Y.S.; Sztul, E. Hassles with taking out the garbage: Aggravating aggresomes. Traffic 2002, 3, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkey, D.J.; White, M.; Yan, W. HDAC inhibitor modulation of proteotoxicity as a therapeutic approach in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2012, 116, 131–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibenhener, M.L.; Babu, J.R.; Geetha, T.; Wong, H.C.; Krishna, N.R.; Wooten, M.W. Sequestosome 1/p62 is a polyubiquitin chain binding protein involved in ubiquitin proteasome degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 24, 8055–8068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heir, R.; Ablasou, C.; Dumontier, E.; Elliott, M.; Fagotto-Kaufmann, C.; Bedford, F.K. The UBL domain of PLIC-1 regulates aggresome formation. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, B.G.; Pittman, R.N. The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin 3 regulates aggresome formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 4330–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigley, W.C.; Fabunmi, R.P.; Lee, M.G.; Marino, C.R.; Muallem, S.; DeMartino, G.N.; Thomas, P.J. Dynamic association of proteasomal machinery with the centrosome. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 145, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, K.; Jiang, Y.; He, Z.; Kitazato, K.; Wang, Y. Cellular defence or viral assist: The dilemma of HDAC6. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrador, J.M.; Cabrero, J.R.; Sancho, D.; Mittelbrunn, M.; Urzainqui, A.; Sanchez-Madrid, F. HDAC6 deacetylase activity links the tubulin cytoskeleton with immune synapse organization. Immunity 2004, 20, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, M.; Cheung, C.Y. Histone deacetylase 6 inhibits influenza A virus release by downregulating the trafficking of viral components to the plasma membrane via its substrate, acetylated microtubules. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11229–11239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.P.; Tanaka, F.; Robitschek, J.; Sandoval, C.M.; Taye, A.; Markovic-Plese, S.; Fischbeck, K.H. Aggresomes protect cells by enhancing the degradation of toxic polyglutamine-containing protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shevchenko, A.; Shevchenko, A.; Berk, A.J. Adenovirus exploits the cellular aggresome response to accelerate inactivation of the MRN complex. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 14004–14016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohner, K.; Nagel, C.H.; Sodeik, B. Viral stop-and-go along microtubules: Taking a ride with dynein and kinesins. Trends Microbiol. 2005, 13, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meriin, A.B.; Wang, Y.; Sherman, M.Y. Isolation of aggresomes and other large aggregates. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2010, 48, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, R.; Nanduri, P.; Rao, Y.; Panichelli, R.S.; Ito, A.; Yoshida, M.; Yao, T.P. Proteasomes activate aggresome disassembly and clearance by producing unanchored ubiquitin chains. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbert, C.; Guardiola, A.; Shao, R.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Ito, A.; Nixon, A.; Yoshida, M.; Wang, X.F.; Yao, T.P. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature 2002, 417, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Kovacs, J.J.; McLaurin, A.; Vance, J.M.; Ito, A.; Yao, T.P. The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell 2003, 115, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemi, L.M.; Almawi, A.W.; Lefebvre, K.J.; Schild-Poulter, C. Aggresome formation is regulated by RanBPM through an interaction with HDAC6. Biol. Open 2014, 3, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, A.; Saccoccia, F.; Gennari, N.; Gimmelli, R.; Nizi, E.; Lalli, C.; Paonessa, G.; Papoff, G.; Bresciani, A.; Ruberti, G. Identification of novel multi-stage histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors that impair Schistosoma mansoni viability and egg production. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, M.S.; de Armas-Rillo, L.; Barroso-Gonzalez, J.; Ziglio, S.; Batisse, J.; Dubois, N.; Marrero-Hernandez, S.; Borel, S.; Garcia-Exposito, L.; Biard-Piechaczyk, M.; et al. The HDAC6/APOBEC3G complex regulates HIV-1 infectiveness by inducing Vif autophagic degradation. Retrovirology 2015, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussart, S.; Courcoul, M.; Bessou, G.; Douaisi, M.; Duverger, Y.; Vigne, R.; Decroly, E. The Vif protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is posttranslationally modified by ubiquitin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 315, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehle, A.; Strack, B.; Ancuta, P.; Zhang, C.; McPike, M.; Gabuzda, D. Vif overcomes the innate antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by promoting its degradation in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 7792–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, L.; Li, D.; Sun, X.; Shi, X.; Karna, P.; Yang, W.; Liu, M.; Qiao, W.; Aneja, R.; Zhou, J. Regulation of Tat acetylation and transactivation activity by the microtubule-associated deacetylase HDAC6. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 9280–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusinzon, I.; Horvath, C.M. Positive and negative regulation of the innate antiviral response and beta interferon gene expression by deacetylation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 26, 3106–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Fensterl, V.; Zhang, Y.; Veleeparambil, M.; Wetzel, J.L.; Sen, G.C. Inhibition of viral pathogenesis and promotion of the septic shock response to bacterial infection by IRF-3 are regulated by the acetylation and phosphorylation of its coactivators. MBio 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.J.; Lee, H.C.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, W.K.; Jang, D.J.; Yoon, J.E.; Choi, Y.I.; Kim, S.; et al. HDAC6 regulates cellular viral RNA sensing by deacetylation of RIG-I. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajitani, N.; Satsuka, A.; Yoshida, S.; Sakai, H. HPV18 E1^E4 is assembled into aggresome-like compartment and involved in sequestration of viral oncoproteins. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deretic, V.; Levine, B. Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doring, T.; Zeyen, L.; Bartusch, C.; Prange, R. Hepatitis B Virus Subverts the Autophagy Elongation Complex Atg5-12/16L1 and Does Not Require Atg8/LC3 Lipidation for Viral Maturation. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagosome formation: Core machinery and adaptations. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatman, E.; Oyer, R.; Shives, K.D.; Hedman, K.; Brault, A.C.; Tyler, K.L.; Beckham, J.D. West Nile virus growth is independent of autophagy activation. Virology 2012, 433, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafren, A.; Ustun, S.; Hochmuth, A.; Svenning, S.; Johansen, T.; Hofius, D. Turnip Mosaic Virus Counteracts Selective Autophagy of the Viral Silencing Suppressor HCpro. Plant. Physiol. 2018, 176, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Ge, X.; Xin, L.; Zhou, L.; Guo, X.; Yang, H. Nonstructural proteins 2C and 3D are involved in autophagy as induced by the encephalomyocarditis virus. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozieres, A.; Viret, C.; Faure, M. Autophagy in Measles Virus Infection. Viruses 2017, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, N.N.; Inagaki, F. Mechanisms of Autophagy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2015, 44, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohli, L.; Roth, K.A. Autophagy: Cerebral home cooking. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Shi, H.; Ni, W.; Shi, M.; Meng, L.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y.; Guo, F.; Wang, P.; Qiao, J.; et al. Lentivirus-mediated Bos taurus bta-miR-29b overexpression interferes with bovine viral diarrhoea virus replication and viral infection-related autophagy by directly targeting ATG14 and ATG9A in Madin-Darby bovine kidney cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, R., Jr.; Sirasanagandla, S.; Fernandez, A.F.; Wei, Y.; Dong, X.; Franco, L.; Zou, Z.; Marchal, C.; Lee, M.Y.; Clapp, D.W.; et al. Fanconi Anemia Proteins Function in Mitophagy and Immunity. Cell 2016, 165, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasztor, K.; Orosz, L.; Seprenyi, G.; Megyeri, K. Rubella virus perturbs autophagy. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 203, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Lund, J.M.; Ramanathan, B.; Mizushima, N.; Iwasaki, A. Autophagy-dependent viral recognition by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Science 2007, 315, 1398–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Kang, K.H.; Spector, S.A. Production of interferon alpha by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells is dependent on induction of autophagy. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Mattei, L.M.; Steinberg, B.E.; Alberts, P.; Lee, Y.H.; Chervonsky, A.; Mizushima, N.; Grinstein, S.; Iwasaki, A. In vivo requirement for Atg5 in antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Immunity 2010, 32, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paludan, C.; Schmid, D.; Landthaler, M.; Vockerodt, M.; Kube, D.; Tuschl, T.; Munz, C. Endogenous MHC class II processing of a viral nuclear antigen after autophagy. Science 2005, 307, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchet, F.P.; Moris, A.; Nikolic, D.S.; Lehmann, M.; Cardinaud, S.; Stalder, R.; Garcia, E.; Dinkins, C.; Leuba, F.; Wu, L.; et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 inhibition of immunoamphisomes in dendritic cells impairs early innate and adaptive immune responses. Immunity 2010, 32, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B.; Mizushima, N.; Virgin, H.W. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 2011, 469, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Levine, B. Autophagy and viruses: Adversaries or allies? J. Innate Immun. 2013, 5, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Luo, H. Interplay between the cellular autophagy machinery and positive-stranded RNA viruses. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2012, 44, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denizot, M.; Varbanov, M.; Espert, L.; Robert-Hebmann, V.; Sagnier, S.; Garcia, E.; Curriu, M.; Mamoun, R.; Blanco, J.; Biard-Piechaczyk, M. HIV-1 gp41 fusogenic function triggers autophagy in uninfected cells. Autophagy 2008, 4, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiramel, A.I.; Brady, N.R.; Bartenschlager, R. Divergent roles of autophagy in virus infection. Cells 2013, 2, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.; Chava, S.; Aydin, Y.; Chandra, P.K.; Ferraris, P.; Chen, W.; Balart, L.A.; Wu, T.; Garry, R.F. Hepatitis C Virus Infection Induces Autophagy as a Prosurvival Mechanism to Alleviate Hepatic ER-Stress Response. Viruses 2016, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, P.Y.; Chen, S.S. Activation of the unfolded protein response and autophagy after hepatitis C virus infection suppresses innate antiviral immunity in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimoto-Matsuzaki, K.; Saito, H.; Takekawa, M. TIA1 oxidation inhibits stress granule assembly and sensitizes cells to stress-induced apoptosis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, P.E.; Meiffren, G.; Gregoire, I.P.; Pontini, G.; Richetta, C.; Flacher, M.; Azocar, O.; Vidalain, P.O.; Vidal, M.; Lotteau, V.; et al. Autophagy induction by the pathogen receptor CD46. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 6, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, N.; Kritsiligkou, P.; Grant, C.M. ER stress causes widespread protein aggregation and prion formation. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 2295–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markmiller, S.; Fulzele, A.; Higgins, R.; Leonard, M.; Yeo, G.W.; Bennett, E.J. Active Protein Neddylation or Ubiquitylation Is Dispensable for Stress Granule Dynamics. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroder, M.; Kaufman, R.J. ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat Res. 2005, 569, 29–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.; Kedersha, N. RNA granules: Post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchan, J.R.; Parker, R. Eukaryotic stress granules: The ins and outs of translation. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B’Chir, W.; Maurin, A.C.; Carraro, V.; Averous, J.; Jousse, C.; Muranishi, Y.; Parry, L.; Stepien, G.; Fafournoux, P.; Bruhat, A. The eIF2alpha/ATF4 pathway is essential for stress-induced autophagy gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 7683–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Kuo, S.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Fu, P.J.; Lin, Y.S.; Yeh, T.M.; Liu, H.S. Dengue virus-induced ER stress is required for autophagy activation, viral replication, and pathogenesis both in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N. Physiological functions of autophagy. Curr Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009, 335, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, J.R.; Kolaitis, R.M.; Taylor, J.P.; Parker, R. Eukaryotic stress granules are cleared by autophagy and Cdc48/VCP function. Cell 2013, 153, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogov, V.; Dotsch, V.; Johansen, T.; Kirkin, V. Interactions between autophagy receptors and ubiquitin-like proteins form the molecular basis for selective autophagy. Mol. Cell 2014, 53, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhu, G.; Tang, Y.; Yan, J.; Han, S.; Yin, J.; Peng, B.; He, X.; Liu, W. HDAC6, A Novel Cargo for Autophagic Clearance of Stress Granules, Mediates the Repression of the Type I Interferon Response During Coxsackievirus A16 Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, Z.; Shewmaker, F.; Pandey, U.B. Stress granules at the intersection of autophagy and ALS. Brain Res. 2016, 1649, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamud, Y.; Qu, J.; Xue, Y.C.; Liu, H.; Deng, H.; Luo, H. CALCOCO2/NDP52 and SQSTM1/p62 differentially regulate coxsackievirus B3 propagation. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 1062–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krick, R.; Bremer, S.; Welter, E.; Schlotterhose, P.; Muehe, Y.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Thumm, M. Cdc48/p97 and Shp1/p47 regulate autophagosome biogenesis in concert with ubiquitin-like Atg8. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panas, M.D.; Schulte, T.; Thaa, B.; Sandalova, T.; Kedersha, N.; Achour, A.; McInerney, G.M. Viral and cellular proteins containing FGDF motifs bind G3BP to block stress granule formation. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente-Echeverria, F.; Melnychuk, L.; Vyboh, K.; Ajamian, L.; Gallouzi, I.E.; Bernard, N.; Mouland, A.J. eEF2 and Ras-GAP SH3 domain-binding protein (G3BP1) modulate stress granule assembly during HIV-1 infection. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathans, R.; Chu, C.Y.; Serquina, A.K.; Lu, C.C.; Cao, H.; Rana, T.M. Cellular microRNA and P bodies modulate host-HIV-1 interactions. Mol. Cell 2009, 34, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, J.D.; Tsai, W.C.; Lloyd, R.E. Multiple Poliovirus Proteins Repress Cytoplasmic RNA Granules. Viruses 2015, 7, 6127–6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netherton, C.; Moffat, K.; Brooks, E.; Wileman, T. A guide to viral inclusions, membrane rearrangements, factories, and viroplasm produced during virus replication. Adv. Virus Res. 2007, 70, 101–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolino, E.; Schmitz, R.; Loroch, S.; Caragliano, E.; Schneider, C.; Rizzato, M.; Kim, Y.H.; Krause, E.; Juranic Lisnic, V.; Sickmann, A.; et al. Herpesviruses induce aggregation and selective autophagy of host signalling proteins NEMO and RIPK1 as an immune-evasion mechanism. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granato, M.; Santarelli, R.; Farina, A.; Gonnella, R.; Lotti, L.V.; Faggioni, A.; Cirone, M. Epstein-barr virus blocks the autophagic flux and appropriates the autophagic machinery to enhance viral replication. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 12715–12726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemball, C.C.; Alirezaei, M.; Flynn, C.T.; Wood, M.R.; Harkins, S.; Kiosses, W.B.; Whitton, J.L. Coxsackievirus infection induces autophagy-like vesicles and megaphagosomes in pancreatic acinar cells in vivo. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 12110–12124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennemann, N.J.; Coyne, C.B. Catch me if you can: The link between autophagy and viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, W.T.; Giddings, T.H., Jr.; Taylor, M.P.; Mulinyawe, S.; Rabinovitch, M.; Kopito, R.R.; Kirkegaard, K. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidal, A.M.; Cyr, D.P.; Hill, R.J.; Lee, P.W.; McCormick, C. Subversion of autophagy by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus impairs oncogene-induced senescence. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Lei, H.Y.; Liu, M.T.; Wang, J.R.; Chen, S.H.; Jiang-Shieh, Y.F.; Lin, Y.S.; Yeh, T.M.; Liu, C.C.; Liu, H.S. Autophagic machinery activated by dengue virus enhances virus replication. Virology 2008, 374, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).