Nonstructural Proteins of Alphavirus—Potential Targets for Drug Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

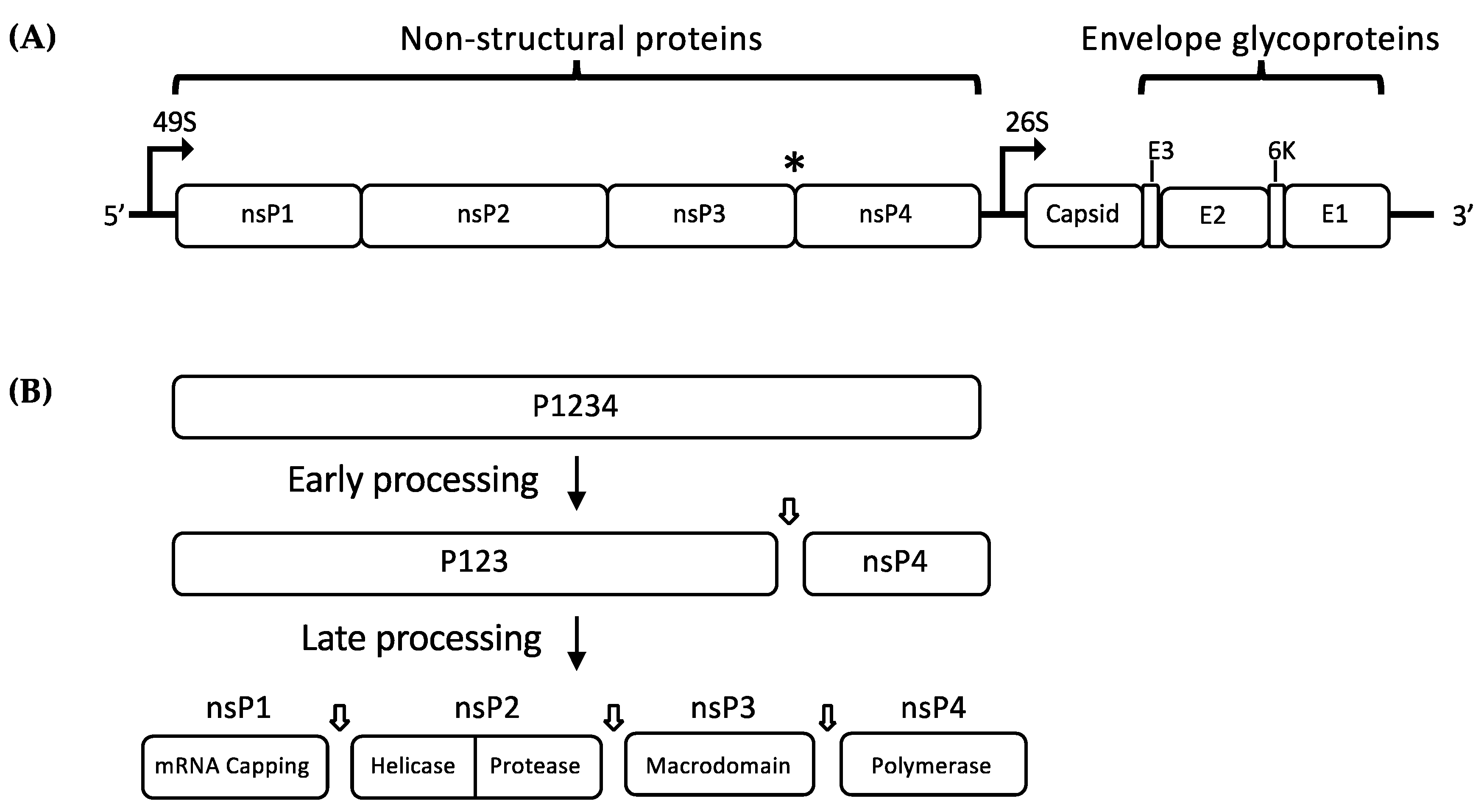

Molecular Virology and Genome Organization

2. Roles and Function of Non-Structural Proteins

2.1. Non-Structural Proteins (nsPs)

2.1.1. Non-Structural Protein 1 (nsP1)

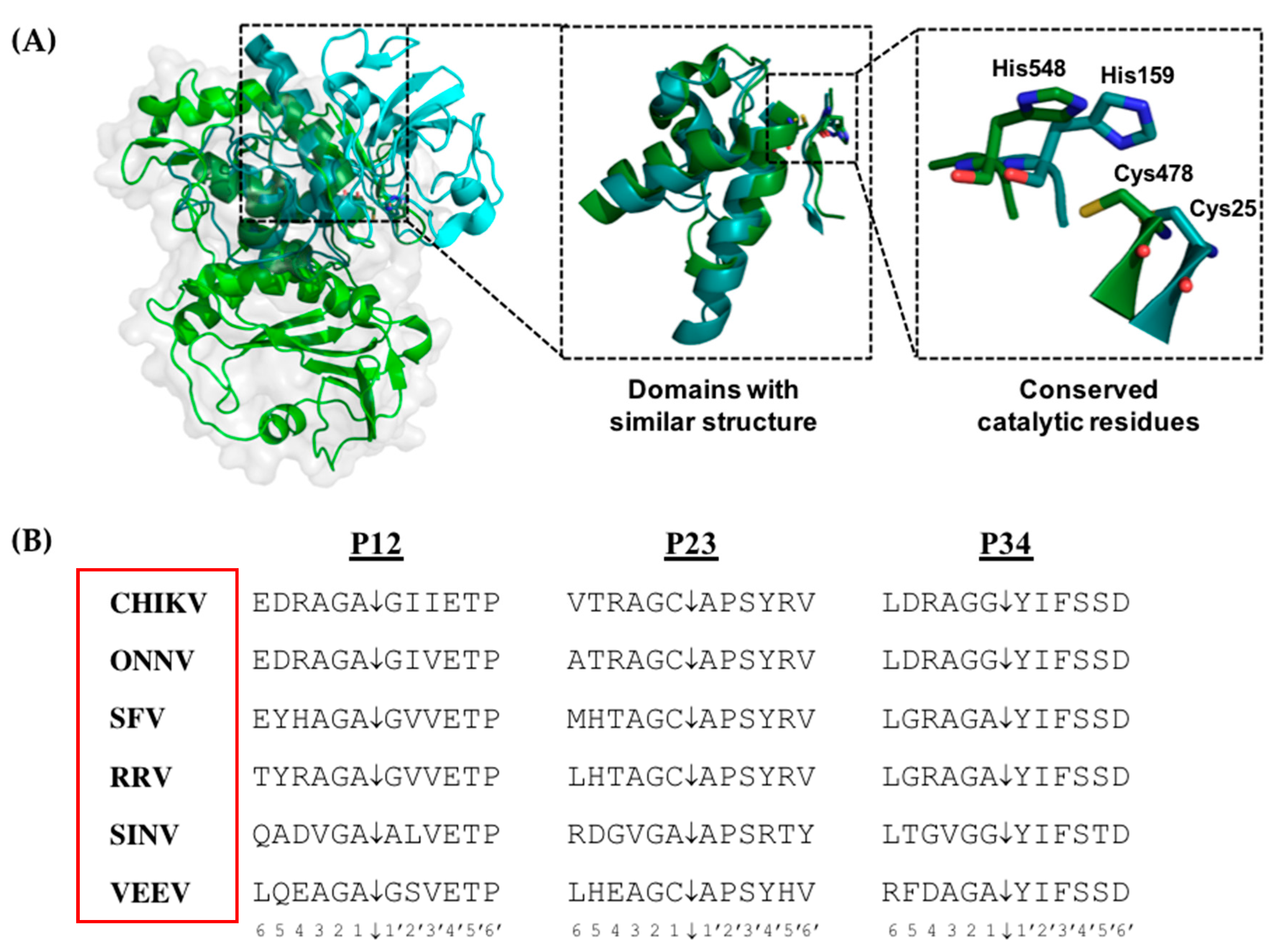

2.1.2. Non-Structural Protein 2 (nsP2)

2.1.3. Non-Structural Protein 3 (nsP3)

2.1.4. Non-Structural Protein 4 (nsP4)

2.2. Viral Target Proteins for Drug Development

3. Chemotherapeutics Targeting Viral Non-Structural Proteins

3.1. Antivirals against nsP2 Protease

3.2. Inhibitors of Other nsPs

4. Concluding Remarks and Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strauss, J.H.; Strauss, E.G. The alphaviruses: Gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 58, 491–562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laine, M.; Luukkainen, R.; Toivanen, A. Sindbis viruses and other alphaviruses as cause of human arthritic disease. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, K.E.; Twenhafel, N.A. Review paper: Pathology of animal models of alphavirus encephalitis. Vet. Pathol. 2010, 47, 790–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgherini, G.; Poubeau, P.; Staikowsky, F.; Lory, M.; Le Moullec, N.; Becquart, J.P.; Wengling, C.; Michault, A.; Paganin, F. Outbreak of chikungunya on Reunion Island: Early clinical and laboratory features in 157 adult patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, F.; Parola, P.; Grandadam, M.; Fourcade, S.; Oliver, M.; Brouqui, P.; Hance, P.; Kraemer, P.; Ali Mohamed, A.; de Lamballerie, X.; et al. Chikungunya infection: An emerging rheumatism among travelers returned from Indian Ocean islands. Report of 47 cases. Medicine 2007, 86, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pialoux, G.; Gauzere, B.A.; Jaureguiberry, S.; Strobel, M. Chikungunya, an epidemic arbovirosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007, 7, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimunda, S.P.; Vijayachari, P.; Uppoor, R.; Sugunan, A.P.; Singh, S.S.; Rai, S.K.; Sudeep, A.B.; Muruganandam, N.; Chaitanya, I.K.; Guruprasad, D.R. Clinical progression of chikungunya fever during acute and chronic arthritic stages and the changes in joint morphology as revealed by imaging. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 104, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Ou Alla, S.; Combe, B. Arthritis after infection with Chikungunya virus. Best Prac. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011, 25, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbrook, M.R.; Gowen, B.B. Animal models of highly pathogenic RNA viral infections: Encephalitis viruses. Antivir. Res. 2008, 78, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacks, M.A.; Paessler, S. Encephalitic alphaviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 140, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renault, P.; Solet, J.L.; Sissoko, D.; Balleydier, E.; Larrieu, S.; Filleul, L.; Lassalle, C.; Thiria, J.; Rachou, E.; de Valk, H.; et al. A major epidemic of chikungunya virus infection on Reunion Island, France, 2005–2006. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 77, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Chikungunya—Fact Sheet; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, E.G.; Rice, C.M.; Strauss, J.H. Complete nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of Sindbis virus. Virology 1984, 133, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, E.G.; Rice, C.M.; Strauss, J.H. Sequence coding for the alphavirus nonstructural proteins is interrupted by an opal termination codon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 5271–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, R.J.; Hardy, W.R.; Shirako, Y.; Strauss, J.H. Cleavage-site preferences of Sindbis virus polyproteins containing the non-structural proteinase. Evidence for temporal regulation of polyprotein processing in vivo. EMBO J. 1990, 9, 2631–2638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vasiljeva, L.; Merits, A.; Golubtsov, A.; Sizemskaja, V.; Kaariainen, L.; Ahola, T. Regulation of the sequential processing of Semliki Forest virus replicase polyprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 41636–41645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, D.J.; Sawicki, S.G.; Sawicki, D.L. Solubilization and immunoprecipitation of alphavirus replication complexes. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shirako, Y.; Strauss, J.H. Regulation of Sindbis virus RNA replication: Uncleaved P123 and nsP4 function in minus-strand RNA synthesis, whereas cleaved products from P123 are required for efficient plus-strand RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 1874–1885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.L. The cell biology of Chikungunya virus infection. Cell. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, R.; Owen, K.E.; Tellinghuisen, T.L.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Kuhn, R.J. Alphavirus nucleocapsid protein contains a putative coiled coil alpha-helix important for core assembly. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstrom, M.; Liljestrom, P.; Garoff, H. Membrane protein lateral interactions control Semliki Forest virus budding. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paredes, A.M.; Brown, D.T.; Rothnagel, R.; Chiu, W.; Schoepp, R.J.; Johnston, R.E.; Prasad, B.V. Three-dimensional structure of a membrane-containing virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 9095–9099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, R.H.; Kuhn, R.J.; Olson, N.H.; Rossmann, M.G.; Choi, H.K.; Smith, T.J.; Baker, T.S. Nucleocapsid and glycoprotein organization in an enveloped virus. Cell 1995, 80, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, E.J.; Clarke, M.; Gowen, B.E.; Rutten, T.; Fuller, S.D. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals the functional organization of an enveloped virus, Semliki Forest virus. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescar, J.; Roussel, A.; Wien, M.W.; Navaza, J.; Fuller, S.D.; Wengler, G.; Wengler, G.; Rey, F.A. The Fusion glycoprotein shell of Semliki Forest virus: An icosahedral assembly primed for fusogenic activation at endosomal pH. Cell 2001, 105, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourisseau, M.; Schilte, C.; Casartelli, N.; Trouillet, C.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Rudnicka, D.; Sol-Foulon, N.; Le Roux, K.; Prevost, M.C.; Fsihi, H.; et al. Characterization of reemerging chikungunya virus. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kielian, M.; Rey, F.A. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: More than one way to make a hairpin. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, M.; Helenius, A. Virus entry: Open sesame. Cell 2006, 124, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, A.T.; White, M.A.; Watowich, S.J. The crystal structure of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis alphavirus nsP2 protease. Structure 2006, 14, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Compton, J.R.; Leary, D.H.; Olson, M.A.; Lee, M.S.; Cheung, J.; Ye, W.; Ferrer, M.; Southall, N.; Jadhav, A.; et al. Kinetic, Mutational, and Structural Studies of the Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus Nonstructural Protein 2 Cysteine Protease. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 3007–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, J.; Franklin, M.; Mancia, F.; Rudolph, M.; Cassidy, M.; Gary, E.; Burshteyn, F.; Love, J. Structure of the Chikungunya virus nsP2 protease. Unpublished work. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, G.; Yost, S.A.; Miller, M.T.; Elrod, E.J.; Grakoui, A.; Marcotrigiano, J. Structural and functional insights into alphavirus polyprotein processing and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16534–16539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, G.J.; Sheahan, B.J.; Liljestrom, P. The molecular pathogenesis of Semliki Forest virus: A model virus made useful? J. Gen. Virol. 1999, 80 Pt 9, 2287–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, J.C.; Sokoloski, K.J.; Gebhart, N.N.; Hardy, R.W. Alphavirus RNA synthesis and non-structural protein functions. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 2483–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorchakov, R.; Frolova, E.; Sawicki, S.; Atasheva, S.; Sawicki, D.; Frolov, I. A new role for ns polyprotein cleavage in Sindbis virus replication. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 6218–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemm, J.A.; Rice, C.M. Assembly of functional Sindbis virus RNA replication complexes: Requirement for coexpression of P123 and P34. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 1905–1915. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lemm, J.A.; Rumenapf, T.; Strauss, E.G.; Strauss, J.H.; Rice, C.M. Polypeptide requirements for assembly of functional Sindbis virus replication complexes: A model for the temporal regulation of minus- and plus-strand RNA synthesis. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 2925–2934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cross, R.K. Identification of a unique guanine-7-methyltransferase in Semliki Forest virus (SFV) infected cell extracts. Virology 1983, 130, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakkonen, P.; Hyvönen, M.; Peränen, J.; Kääriäinen, L. Expression of Semliki Forest virus nsP1-specific methyltransferase in insect cells and in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 7418–7425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahola, T.; Kääriäinen, L. Reaction in alphavirus mRNA capping: Formation of a covalent complex of nonstructural protein nsP1 with 7-methyl-GMP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, S.; Stollar, V. Expression of Sindbis virus nsP1 and methyltransferase activity in Escherichia coli. Virology 1991, 184, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decroly, E.; Ferron, F.; Lescar, J.; Canard, B. Conventional and unconventional mechanisms for capping viral mRNA. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 10, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laakkonen, P.; Ahola, T.; Kaariainen, L. The effects of palmitoylation on membrane association of Semliki forest virus RNA capping enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 28567–28571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahola, T.; Lampio, A.; Auvinen, P.; Kaariainen, L. Semliki Forest virus mRNA capping enzyme requires association with anionic membrane phospholipids for activity. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 3164–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampio, A.; Kilpelainen, I.; Pesonen, S.; Karhi, K.; Auvinen, P.; Somerharju, P.; Kaariainen, L. Membrane binding mechanism of an RNA virus-capping enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 37853–37859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spuul, P.; Salonen, A.; Merits, A.; Jokitalo, E.; Kaariainen, L.; Ahola, T. Role of the amphipathic peptide of Semliki forest virus replicase protein nsP1 in membrane association and virus replication. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahola, T.; Kujala, P.; Tuittila, M.; Blom, T.; Laakkonen, P.; Hinkkanen, A.; Auvinen, P. Effects of palmitoylation of replicase protein nsP1 on alphavirus infection. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6725–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gorbalenya, A.E.; Koonin, E.V.; Donchenko, A.P.; Blinov, V.M. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 4713–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiljeva, L.; Merits, A.; Auvinen, P.; Kaariainen, L. Identification of a novel function of the alphavirus capping apparatus. RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity of nsP2. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 17281–17287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpe, Y.A.; Aher, P.P.; Lole, K.S. NTPase and 5′-RNA triphosphatase activities of Chikungunya virus nsP2 protein. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikkonen, M.; Peränen, J.; Kääriäinen, L. ATPase and GTPase activities associated with Semliki Forest virus nonstructural protein nsP2. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 5804–5810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Rumenapf, T.; Strauss, E.G.; Strauss, J.H. Regulation of Semliki Forest virus RNA replication: A model for the control of alphavirus pathogenesis in invertebrate hosts. Virology 2004, 323, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiljeva, L.; Valmu, L.; Kääriäinen, L.; Merits, A. Site-specific protease activity of the carboxyl-terminal domain of Semliki Forest virus replicase protein nsP2. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 30786–30793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, C.; Kutumbarao, N.H.V.; Suhitha, S.; Velmurugan, D. Structure–function relationship of Chikungunya nsP2 protease: A comparative study with papain. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017, 89, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lulla, A.; Lulla, V.; Tints, K.; Ahola, T.; Merits, A. Molecular Determinants of Substrate Specificity for Semliki Forest Virus Nonstructural Protease. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5413–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorchakov, R.; Frolova, E.; Frolov, I. Inhibition of transcription and translation in Sindbis virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 9397–9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breakwell, L.; Dosenovic, P.; Karlsson Hedestam, G.B.; D’Amato, M.; Liljestrom, P.; Fazakerley, J.; McInerney, G.M. Semliki Forest virus nonstructural protein 2 is involved in suppression of the type I interferon response. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8677–8684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolov, I.; Garmashova, N.; Atasheva, S.; Frolova, E.I. Random insertion mutagenesis of sindbis virus nonstructural protein 2 and selection of variants incapable of downregulating cellular transcription. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 9031–9044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalla, N.; Sun, C.; Metthew Lam, L.K.; Gardner, C.L.; Ryman, K.D.; Klimstra, W.B. Host translation shutoff mediated by non-structural protein 2 is a critical factor in the antiviral state resistance of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Virology 2016, 496, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malet, H.; Coutard, B.; Jamal, S.; Dutartre, H.; Papageorgiou, N.; Neuvonen, M.; Ahola, T.; Forrester, N.; Gould, E.A.; Lafitte, D.; et al. The crystal structures of Chikungunya and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus nsP3 macro domains define a conserved adenosine binding pocket. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6534–6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuittila, M.T.; Santagati, M.G.; Röyttä, M.; Määttä, J.A.; Hinkkanen, A.E. Replicase complex genes of Semliki Forest virus confer lethal neurovirulence. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4579–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, N.L.; Guerbois, M.; Seymour, R.L.; Spratt, H.; Weaver, S.C. Vector-borne transmission imposes a severe bottleneck on an RNA virus population. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, J.; Villoing, S.; Bremont, M.; Castric, J.; Pfeffer, M.; Jewhurst, V.; McLoughlin, M.; Rodseth, O.; Christie, K.E.; Koumans, J.; et al. Comparison of two aquatic alphaviruses, salmon pancreas disease virus and sleeping disease virus, by using genome sequence analysis, monoclonal reactivity, and cross-infection. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 6155–6163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubach, J.K.; Wasik, B.R.; Rupp, J.C.; Kuhn, R.J.; Hardy, R.W.; Smith, J.L. Characterization of purified Sindbis virus nsP4 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity in vitro. Virology 2009, 384, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, J.C.; Jundt, N.; Hardy, R.W. Requirement for the Amino-Terminal Domain of Sindbis Virus nsP4 during Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 3449–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, S.; Hardy, R.W.; Smith, J.L.; Kuhn, R.J. Catalytic core of alphavirus nonstructural protein nsP4 possesses terminal adenylyltransferase activity. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 9962–9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.W.; Tan, Y.B.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Lim, B.T.; Cornvik, T.; Lescar, J.; Ng, L.F.P.; Luo, D. Chikungunya virus nsP4 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase core domain displays detergent-sensitive primer extension and terminal adenylyltransferase activities. Antivir. Res. 2017, 143, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietila, M.K.; Hellstrom, K.; Ahola, T. Alphavirus polymerase and RNA replication. Virus Res. 2017, 234, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimley, P.M.; Berezesky, I.K.; Friedman, R.M. Cytoplasmic structures associated with an arbovirus infection: Loci of viral ribonucleic acid synthesis. J. Virol. 1968, 2, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kujala, P.; Ikaheimonen, A.; Ehsani, N.; Vihinen, H.; Auvinen, P.; Kaariainen, L. Biogenesis of the Semliki Forest virus RNA replication complex. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 3873–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolova, E.I.; Gorchakov, R.; Pereboeva, L.; Atasheva, S.; Frolov, I. Functional Sindbis virus replicative complexes are formed at the plasma membrane. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11679–11695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atasheva, S.; Fish, A.; Fornerod, M.; Frolova, E.I. Venezuelan equine Encephalitis virus capsid protein forms a tetrameric complex with CRM1 and importin α/β that obstructs nuclear pore complex function. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 4158–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuvonen, M.; Kazlauskas, A.; Martikainen, M.; Hinkkanen, A.; Ahola, T.; Saksela, K. SH3 domain-mediated recruitment of host cell amphiphysins by alphavirus nsP3 promotes viral RNA replication. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Hur, S. Helicases in Antiviral Immunity: Dual Properties as Sensors and Effectors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrejeva, J.; Childs, K.S.; Young, D.F.; Carlos, T.S.; Stock, N.; Goodbourn, S.; Randall, R.E. The V proteins of paramyxoviruses bind the IFN-inducible RNA helicase, mda-5, and inhibit its activation of the IFN-β promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17264–17269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, F.; Li, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xu, L.G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.P.; Chen, D.; Zhai, Z.; Zhong, B.; et al. Negative regulation of MDA5- but not RIG-I-mediated innate antiviral signaling by the dihydroxyacetone kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 11706–11711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneyama, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Natsukawa, T.; Shinobu, N.; Imaizumi, T.; Miyagishi, M.; Taira, K.; Akira, S.; Fujita, T. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertel, K.J.; Benefield, D.; Castano-Diez, D.; Pennington, J.G.; Horswill, M.; den Boon, J.A.; Otegui, M.S.; Ahlquist, P. Cryo-electron tomography reveals novel features of a viral RNA replication compartment. eLife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopek, B.G.; Perkins, G.; Miller, D.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Ahlquist, P. Three-dimensional analysis of a viral RNA replication complex reveals a virus-induced mini-organelle. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, J.; Lopez-Iglesias, C.; Tzeng, W.P.; Frey, T.K.; Fernandez, J.J.; Risco, C. Three-dimensional structure of Rubella virus factories. Virology 2010, 405, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsch, S.; Miller, S.; Romero-Brey, I.; Merz, A.; Bleck, C.K.; Walther, P.; Fuller, S.D.; Antony, C.; Krijnse-Locker, J.; Bartenschlager, R. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froshauer, S.; Kartenbeck, J.; Helenius, A. Alphavirus RNA replicase is located on the cytoplasmic surface of endosomes and lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 107, 2075–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellstrom, K.; Kallio, K.; Merilainen, H.M.; Jokitalo, E.; Ahola, T. Ability of minus strands and modified plus strands to act as templates in Semliki Forest virus RNA replication. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, J.; Rajasekharan, S.; Gulati, S.; Dudha, N.; Gupta, A.; Chaudhary, V.K.; Gupta, S. Network mapping among the functional domains of Chikungunya virus nonstructural proteins. Proteins 2014, 82, 2403–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreejith, R.; Rana, J.; Dudha, N.; Kumar, K.; Gabrani, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Gupta, A.; Vrati, S.; Chaudhary, V.K.; Gupta, S. Mapping interactions of Chikungunya virus nonstructural proteins. Virus Res. 2012, 169, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lulla, V.; Sawicki, D.L.; Sawicki, S.G.; Lulla, A.; Merits, A.; Ahola, T. Molecular defects caused by temperature-sensitive mutations in Semliki Forest virus nsP1. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 9236–9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salonen, A.; Vasiljeva, L.; Merits, A.; Magden, J.; Jokitalo, E.; Kaariainen, L. Properly folded nonstructural polyprotein directs the semliki forest virus replication complex to the endosomal compartment. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirako, Y.; Strauss, J.H. Requirement for an aromatic amino acid or histidine at the N terminus of Sindbis virus RNA polymerase. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 2310–2315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, D.L.; Sawicki, S.G. A second nonstructural protein functions in the regulation of alphavirus negative-strand RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 3605–3610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fata, C.L.; Sawicki, S.G.; Sawicki, D.L. Modification of Asn374 of nsP1 suppresses a Sindbis virus nsP4 minus-strand polymerase mutant. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 8641–8649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fros, J.J.; Pijlman, G.P. Alphavirus Infection: Host Cell Shut-Off and Inhibition of Antiviral Responses. Viruses 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemm, J.A.; Bergqvist, A.; Read, C.M.; Rice, C.M. Template-dependent initiation of Sindbis virus RNA replication in vitro. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 6546–6553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manns, M.P.; von Hahn, T. Novel therapies for hepatitis C—One pill fits all? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokorna, J.; Machala, L.; Rezacova, P.; Konvalinka, J. Current and Novel Inhibitors of HIV Protease. Viruses 2009, 1, 1209–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, E. The design of drugs for HIV and HCV. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 1001–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, E.G.; de Groot, R.J.; Levinson, R.; Strauss, J.H. Identification of the active site residues in the nsP2 proteinase of Sindbis virus. Virology 1992, 191, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubtsov, A.; Kääriäinen, L.; Caldentey, J. Characterization of the cysteine protease domain of Semliki Forest virus replicase protein nsP2 by in vitro mutagenesis. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rausalu, K.; Utt, A.; Quirin, T.; Varghese, F.S.; Zusinaite, E.; Das, P.K.; Ahola, T.; Merits, A. Chikungunya virus infectivity, RNA replication and non-structural polyprotein processing depend on the nsP2 protease’s active site cysteine residue. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikkonen, M.; Peranen, J.; Kaariainen, L. Nuclear and nucleolar targeting signals of Semliki Forest virus nonstructural protein nsP2. Virology 1992, 189, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikkonen, M.; Peranen, J.; Kaariainen, L. Nuclear targeting of Semliki Forest virus nsP2. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 1994, 9, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fros, J.J.; van der Maten, E.; Vlak, J.M.; Pijlman, G.P. The C-terminal domain of chikungunya virus nsP2 independently governs viral RNA replication, cytopathicity, and inhibition of interferon signaling. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10394–10400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourai, M.; Lucas-Hourani, M.; Gad, H.H.; Drosten, C.; Jacob, Y.; Tafforeau, L.; Cassonnet, P.; Jones, L.M.; Judith, D.; Couderc, T.; et al. Mapping of Chikungunya virus interactions with host proteins identified nsP2 as a highly connected viral component. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3121–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamm, K.; Merits, A.; Sarand, I. Mutations in the nuclear localization signal of nsP2 influencing RNA synthesis, protein expression and cytotoxicity of Semliki Forest virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ching, K.-C.; Ng, L.F.P.; Chai, C.L.L. A compendium of small molecule direct-acting and host-targeting inhibitors as therapies against alphaviruses. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2973–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, A.D.; Kauffman, R.S.; Hurter, P.; Mueller, P. Discovery and development of telaprevir: An NS3-4A protease inhibitor for treating genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, A.Y.; Venkatraman, S. The Discovery and Development of Boceprevir: A Novel, First-generation Inhibitor of the Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4A Serine Protease. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2013, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Chu, Y.; Wang, Y. HIV protease inhibitors: A review of molecular selectivity and toxicity. HIV AIDS 2015, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetto, M.; de Burghgraeve, T.; Delang, L.; Massarotti, A.; Coluccia, A.; Zonta, N.; Gatti, V.; Colombano, G.; Sorba, G.; Silvestri, R.; et al. Computer-aided identification, design and synthesis of a novel series of compounds with selective antiviral activity against chikungunya virus. Antivir. Res. 2013, 98, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.K.; Puusepp, L.; Varghese, F.S.; Utt, A.; Ahola, T.; Kananovich, D.G.; Lopp, M.; Merits, A.; Karelson, M. Design and Validation of Novel Chikungunya Virus Protease Inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 7382–7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.D.; Kirubakaran, P.; Nagarajan, S.; Sakkiah, S.; Muthusamy, K.; Velmurgan, D.; Jeyakanthan, J. Homology modeling, molecular dynamics, e-pharmacophore mapping and docking study of Chikungunya virus nsP2 protease. J. Mol. Model. 2012, 18, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Yu, H.; Keller, P.A. Identification of chikungunya virus nsP2 protease inhibitors using structure-base approaches. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2015, 57, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byler, K.G.; Collins, J.T.; Ogungbe, I.V.; Setzer, W.N. Alphavirus protease inhibitors from natural sources: A homology modeling and molecular docking investigation. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2016, 64, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakat, S.; Delang, L.; Kaptein, S.; Neyts, J.; Leyssen, P.; Jayaprakash, V. Reaching beyond HIV/HCV: Nelfinavir as a potential starting point for broad-spectrum protease inhibitors against dengue and chikungunya virus. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 85938–85949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, A.; Canela, M.D.; Delang, L.; Priego, E.M.; Camarasa, M.J.; Querat, G.; Neyts, J.; Leyssen, P.; Perez-Perez, M.J. Identification of 1,2,3 triazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-7(6H)-ones as novel inhibitors of Chikungunya virus replication. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4000–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigante, A.; Gomez-SanJuan, A.; Delang, L.; Li, C.; Bueno, O.; Gamo, A.M.; Priego, E.M.; Camarasa, M.J.; Jochmans, D.; Leyssen, P.; et al. Antiviral activity of 1,2,3 triazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-7(6H)-ones against chikungunya virus targeting the viral capping nsP1. Antivir. Res. 2017, 144, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delang, L.; Li, C.; Tas, A.; Quérat, G.; Albulescu, I.C.; de Burghgraeve, T.; Guerrero, N.A.S.; Gigante, A.; Piorkowski, G.; Decroly, E.; et al. The viral capping enzyme nsP1: A novel target for the inhibition of chikungunya virus infection. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briolant, S.; Garin, D.; Scaramozzino, N.; Jouan, A.; Crance, J.M. In vitro inhibition of Chikungunya and Semliki Forest viruses replication by antiviral compounds: Synergistic effect of interferon-α and ribavirin combination. Antivir. Res. 2004, 61, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothan, H.A.; Bahrani, H.; Mohamed, Z.; Teoh, T.C.; Shankar, E.M.; Rahman, N.A.; Yusof, R. A combination of doxycycline and ribavirin alleviated chikungunya infection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholte, F.E.; Tas, A.; Martina, B.E.; Cordioli, P.; Narayanan, K.; Makino, S.; Snijder, E.J.; van Hemert, M.J. Characterization of synthetic Chikungunya viruses based on the consensus sequence of recent E1-226V isolates. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, L.L.; Beeharry, Y.; Borderia, A.V.; Blanc, H.; Vignuzzi, M. Arbovirus high fidelity variant loses fitness in mosquitoes and mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16038–16043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen-Gagnon, K.; Stapleford, K.A.; Mongelli, V.; Blanc, H.; Failloux, A.-B.; Saleh, M.-C.; Vignuzzi, M. Alphavirus Mutator Variants Present Host-Specific Defects and Attenuation in Mammalian and Insect Models. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urakova, N.; Kuznetsova, V.; Crossman, D.K.; Sokratian, A.; Guthrie, D.B.; Kolykhalov, A.A.; Lockwood, M.A.; Natchus, M.G.; Crowley, M.R.; Painter, G.R.; et al. β-d-N(4)-hydroxycytidine is a potent anti-alphavirus compound that induces high level of mutations in viral genome. J. Virol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delang, L.; Guerrero, N.S.; Tas, A.; Quérat, G.; Pastorino, B.; Froeyen, M.; Dallmeier, K.; Jochmans, D.; Herdewijn, P.; Bello, F.; et al. Mutations in the chikungunya virus non-structural proteins cause resistance to favipiravir (T-705), a broad-spectrum antiviral. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 2770–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, Y.; Orba, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Carr, M.J.; Nobori, H.; Sato, A.; Hall, W.W.; Sawa, H. Discovery of a novel antiviral agent targeting the nonstructural protein 4 (nsP4) of chikungunya virus. Virology 2017, 505, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-Structural Protein | Domain Function | Virus | PDB ID | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nsP1 | mRNA capping | SFV | 1FW5 | [45] |

| nsP2 | NTPase/HelicaseProtease | - VEEV CHIKV SINV | - 2HWK, 5EZQ 3TRK 4GUA | - [29,30] [31] [32] |

| nsP3 | Macrodomain | VEEV CHIKV SINV | 3GQE 3GPG 4GUA | [60] [60] [32] |

| nsP4 | RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase | - | - | [32] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abu Bakar, F.; Ng, L.F.P. Nonstructural Proteins of Alphavirus—Potential Targets for Drug Development. Viruses 2018, 10, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10020071

Abu Bakar F, Ng LFP. Nonstructural Proteins of Alphavirus—Potential Targets for Drug Development. Viruses. 2018; 10(2):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10020071

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbu Bakar, Farhana, and Lisa F. P. Ng. 2018. "Nonstructural Proteins of Alphavirus—Potential Targets for Drug Development" Viruses 10, no. 2: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10020071

APA StyleAbu Bakar, F., & Ng, L. F. P. (2018). Nonstructural Proteins of Alphavirus—Potential Targets for Drug Development. Viruses, 10(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10020071