Property Rights, Village Political System, and Forestry Investment: Evidence from China’s Collective Forest Tenure Reform

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Econometric Specification

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Basic Economic Model: Market Factors

2.1.2. The Effects of Institutional Arrangements

2.1.3. The Effects of Social Factors

2.1.4. The Effects of Ecological Factors

2.2. Empirical Approach

2.3. Econometric Approach

3. Data and Empirical Measurements

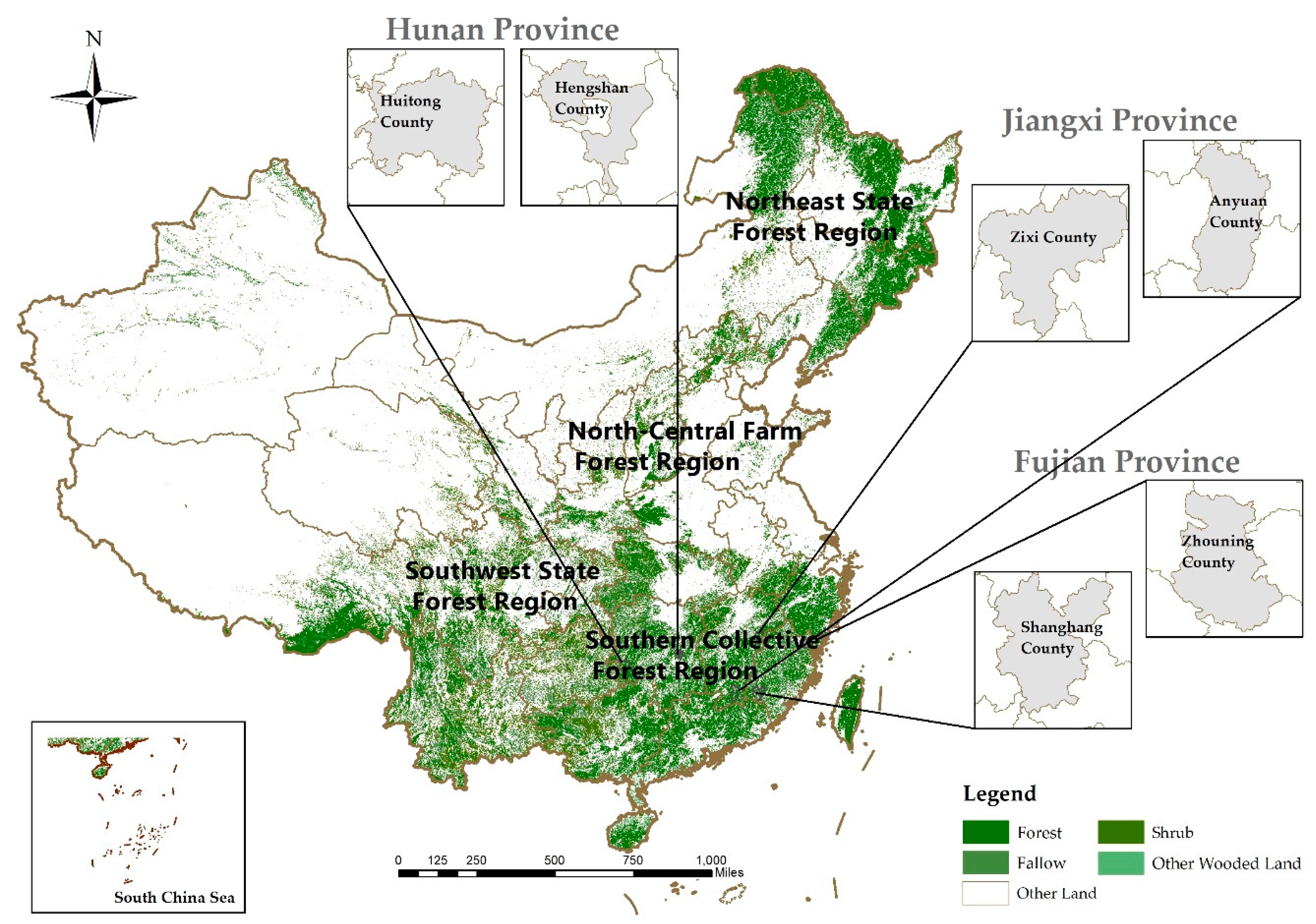

3.1. The Study Area and Data Collection

3.2. Variables Used

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Measuring Property Rights

3.2.3. Measuring Village Democracy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Estimation Results

4.2.1. The Effects of Property Rights

4.2.2. The Effects of Village Democracy

4.2.3. Other Determinants of Investments

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Property Right Component | Property Right Policy | Property Right Assessment Based on Farmer’s Response | Mean | Std. Dev. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary Indicator | Third-Level Indicator | |||||

| Use Right | Right to Use Forestland | Scale | According to household forestland area from small to large (five levels: less than 1 ha; 1–3 ha; 3–5 ha; 5–7 ha; more than 7 ha), 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 respectively | 0.58 | 0.19 | |

| Tenure | According to household forestland tenure from short to long (five levels: less than 10 years; 10–30 years; 30–50 years; 50–70 years; more than 70 years), 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 respectively | 0.51 | 0.14 | |||

| Right to select the ways to use forestland | According to the accumulative number of rights to select the ways to use forestland (including rights to transfer forestland to farmland or nonforestry land, to select tree species, and to conduct under-forest economy) from small to large, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 respectively | 0.71 | 0.22 | |||

| Right to own ground attachment 1 | Does not have the right, 0; Has the right, 1 | 0.83 | 0.10 | |||

| Disposition Right | Right to Mortgage Forests | Conditions for loans | Required minimum stand age | According to the required minimum stand age from old to young (three levels: without requirement; more than 1 year; more than 5 years), 0.2, 0.6, and 1 respectively | 0.39 | 0.51 |

| Required minimum collateral area of mortgaged forests | According to the required minimum collateral area of mortgaged forests from large to small (four levels: more than 30 Ha; more than 10 Ha; more than 5 Ha; without requirement), 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 respectively | 0.48 | 0.22 | |||

| Constraint of loan limit | With constraint, 0; without constraint, 1 | 0.02 | 0.13 | |||

| Rules of mortgage loans | Collateral rate 2 | According to collateral rate of timber forest from low to high (five levels: 40%; 50%; 60%; 70%; 80%), 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 respectively | 0.62 | 0.42 | ||

| Loan period | According to loan period from short to long (four levels: 3 years; 5 years; 8 years; 10 years), 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 respectively | 0.39 | 0.25 | |||

| Loan interest rate 3 | According to loan interest rate from high to low (five levels: 60%, 50%, 46%, 30% and 0% higher than benchmark interest rate), 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 respectively | 0.41 | 0.36 | |||

| Right to Harvest Timber | Allocation of harvest quota 4 | If harvest quota is allocated to township government, 0.2; if harvest quota is allocated to villager committee, 0.6; if harvest quota is directly allocated to household, 1 | 0.32 | 0.29 | ||

| Right to Transfer Forestland | Right to transfer forestland | Does not have the right, 0; has the right, 1 | 0.87 | 0.22 | ||

| Maturity of forest rights market | According to the degree of subjective convenience of treading from low to high (five levels: very inconvenient; inconvenient; normal; fairly convenient; very convenient), 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 respectively | 0.34 | 0.28 | |||

| Right to Inherit Ground Attachment | Right to inherit ground attachment | Does not have the right, 0; has the right, 1 | 0.88 | 0.06 | ||

| Beneficiary Right | Right to Benefit from Forestry Production | Right to market forestry products | Constraint of sales targets 5 | Can only sell forestry products to designated purchasers, 0; without constraint, 1 | 0.59 | 0.40 |

| Constraint of marketing area 5 | According to available marketing area from small to large (three levels: should not sell products outside local county; can sell products outside local counties if pay more taxes; without requirement), 0.2, 0.6, and 1 respectively | 0.72 | 0.24 | |||

| Forestry taxes and fees | Timber tax and fee burden | According to level of timber tax and fee burden from high to low (three levels: 0–100 yuan/m3; 100–160 yuan/m3; above 160 yuan/m3), 0.2, 0.6, and 1 respectively | 0.39 | 0.19 | ||

| Taxes and fees on bamboo and non-timber forests | With taxes and fees, 0; without taxes and fees, 1 | 0.41 | 0.27 | |||

| Forestry subsidy | Subsidy for afforestation | According to level of subsidy for afforestation from low to high (five levels: without subsidy; 0–300 yuan/ha; 300–450 yuan/ha; 450–900 yuan/ha; 900–1500 yuan/ha), 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 respectively | 0.28 | 0.32 | ||

| Subsidy for road construction in forestry area | Without subsidy, 0; with subsidy 1 | 0.02 | 0.12 | |||

| Village Democracy Component | Secondary Indicator | Definition | Village Democracy Assessment Based on Farmer’s Response | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Election | Election Participation | Degree of household involvement in villager representative election | If households did not get involved, ; if households participated in election, ; if households participated in nomination and election, | 0.65 | 0.34 |

| Election Method | Method of villager representative election nomination | If only village leaders could nominate, ; if only previous villager representatives could nominate, ; if everyone could nominate, | 0.36 | 0.48 | |

| Voting Method | Voting accessibility of villager representative election | If the method was non-public voting, ; if the method was semi-public voting, ; if the method was public voting, | 0.82 | 0.31 | |

| Degree of Competitiveness | Competitiveness extent in villager representative election | If the villager representatives were elected by single-candidate elections, ; if the villager representatives were elected by two-candidate elections, ; if the villager representatives were elected by multiple-candidate elections, | 0.68 | 0.26 | |

| Democratic Decision-making | Promotion and Decision-making Meeting 1 | Adequacy of promotion and decision-making meeting | If there was no meeting,; if there was/were decision-making meeting(s),; if there was/were promotion and decision-making meeting(s), | 0.41 | 0.39 |

| Household Discourse Right | Degree of household discourse right in decision-making | If there was no chance for households to give suggestions, ; if there was/were chance(s) for households to give suggestions and part of them was/were valued, ; if there was/were chance(s) for households to give suggestions and all of them were valued, | 0.27 | 0.38 | |

| Democratic Management | Administrative Visibility | Degree of household satisfaction with administrative visibility | If households were not satisfied at all, ; if households were partially satisfied, ; if households were completely satisfied, | 0.48 | 0.37 |

| Financial Management Visibility | Degree of household satisfaction with financial visibility | If households were not satisfied at all, ; if households were partially satisfied, ; if households were completely satisfied, | 0.24 | 0.26 | |

| Democratic Supervision | Supervision Mechanism | Existence of supervision mechanism | If there was no supervision mechanism, ; if there was supervision mechanism, | 0.21 | 0.15 |

References

- State Forestry Administration of China (SFA). China Forest Resource Report (2009−2013); China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese)

- Zhang, H.; Kuuluvainen, J.; Ning, Y.; Liao, W.; Liu, C. Institutional regime, off-farm employment, and the interaction effect: What are the determinants of households’ forestland transfer in China? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Yao, S.; Huo, X. China’s forest tenure reform and institutional change in the new century: What has been implemented and what remains to be pursued? Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. Has China’s new round of collective forest reforms caused an increase in the use of productive forest inputs? Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Forestry Database, State Forestry Administration of China (SFA). Available online: http://data.forestry.gov.cn/lysjk/indexJump.do?url=view/moudle/index (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Liu, P.; Yin, R.; Li, H. China’s forest tenure reform and institutional change at a crossroads. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 72, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Köhlin, G.; Xu, J. Property rights, tenure security and forest investment incentives: Evidence from China’s collective forest tenure reform. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2013, 19, 48–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gong, P.; Han, X.; Wen, Y. The effect of collective forestland tenure reform in China: Does land parcelization reduce forest management intensity? J. For. Econ. 2014, 20, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Lang, R.; Xu, J. Local dynamics driving forest transition: Insights from upland villages in southwest China. Forests 2014, 5, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Ji, Y. Collective forest tenure reform in China: Analysis of pattern and performance. For. Econ. 2008, 9, 7–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Kuuluvainen, J.; Toppinen, A.; Yao, S.; Berghäll, S.; Karppinen, H.; Xue, C.; Yang, L. The effect of China’s new circular collective forest tenure reform on household non-timber forest product production in natural forest protection project regions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Berck, P.; Xu, J. The effect on forestation of the collective forest tenure reform in China. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 38, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Buongiorno, J.; Zhu, S. Domestic and foreign consequences of China’s land tenure reform on collective forests. Int. For. Rev. 2012, 14, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Yao, S. Tenure reform, market incentives and farmers’ investment behaviors. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2017, 10, 93–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Yao, Y. Does grassroots democracy reduce income inequality in China? J. Public Econ. 2008, 92, 2182–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- State Council. Advice on Promoting the Collective Forest Tenure Reform in an All-Round Way; State Council: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese)

- Shi, T. Voting and nonvoting in China: Voting behavior in plebiscitary and limited-choice elections. J. Politics 1999, 61, 1115–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Poudyal, N.; Lu, F. Understanding landowners’ interest and willingness to participate in forest certification program in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Xu, J. Forestland rights, tenure types, and farmers’ investment incentives in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Impact of property rights reform on household forest management investment: An empirical study of southern China. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 34, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Han, R. Path to democracy? Assessing village elections in China. J. Contemp. China 2009, 18, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Village democracy and its determinants: Empirical evidence from 400 villages. Sociol. Stud. 2008, 6, 007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Amacher, G.; Xu, J. Village democracy and household welfare: Evidence from rural China. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2017, 22, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, L. Democratic participation, fiscal reform and local governance: Empirical evidence on Chinese villages. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yao, Y. Grassroots democracy and local governance: Evidence from rural China. World Dev. 2007, 35, 1635–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, L.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J. Property rights reform, grassroots democracy and investment incentives. China Econ. Q. 2016, 3, 001. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dewees, P. Trees on farms in Malawi: Private investment, public policy, and farmer choice. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1085–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubbage, F.; Harou, P.; Sills, E. Policy instruments to enhance multi-functional forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, H.; Lintunen, J.; Pohjola, J.; Hetemäki, L.; Uusivuori, J. Investments into forest biorefineries under different price and policy structures. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Haynes, R.; Dutrow, G.; Barber, R.; Vasievich, J. Private investment in forest management and the long-term supply of timber. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1982, 64, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.; Marey, M. Analysis of individual private forestry in northern Spain according to economic factors related to management. J. For. Econ. 2010, 16, 269–295. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, D. Assessing the financial performance of forestry-related investment vehicles: Capital asset pricing model vs. arbitrage pricing theory. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2001, 83, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Stenger, A.; Harou, P. Policy instruments for developing planted forests: Theory and practices in China, the U.S., Brazil, and France. J. For. Econ. 2015, 21, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T. Nonmarket institutions for credit and risk sharing in low-income countries. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Pearse, P. Differences in silvicultural investment under various types of forest tenure in British Columbia. For. Sci. 1996, 42, 442–449. [Google Scholar]

- Laarman, J.; Gregersen, H. Pricing policy in nature-based tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, H.; Deacon, R. Ownership risk, investment, and the use of natural resources. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 526–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, R. Deforestation and ownership: Evidence from historical accounts and contemporary data. Land Econ. 1999, 75, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, R. Women against the State: Political Opportunities and Collective Action Frames in Chile’s Transition to Democracy. Sociol. Forum 1995, 10, 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, D.; Pattanayak, S. Forests in a Market. Economy; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 283–299. ISBN 978-90-481-6177-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, P.; Mejía, E.; Cano, W.; de Jong, W. Smallholder forestry in the western Amazon: Outcomes from forest reforms and emerging policy perspectives. Forests 2016, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Innes, J. The implications of new forest tenure reforms and forestry property markets for sustainable forest management and forest certification in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 129, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikor, T.; Baggio, J. Can smallholders engage in tree plantations? An entitlements analysis from Vietnam. World Dev. 2014, 64, S101–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, S. Markets for forestland use rights: A case study in southern China. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddala, G. Limited-Dependent and Qualitative Variables in Econometrics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983; pp. 315–342. ISBN 0521338255. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, J. Estimation of relationships for limited dependent variables. Econom. J. Econ. Soc. 1958, 26, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W. Econometric Analysis; Pearson Education India: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 915–922. ISBN 978-0-13-139538-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cragg, J. Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econom. J. Econ. Soc. 1971, 39, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Brame, R. Tobit models in social science research: Some limitations and a more general alternative. Sociol. Methods Res. 2003, 31, 364–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015: How Are the World’s Forests Changing? 2nd ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Xu, J.; Xu, X.; Yi, Y.; Hyde, W. Collective forest tenure reform and household energy consumption: A case study in Yunnan province, China. China Econ. Rev. 2017, 12, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G.; Feeny, D. Land tenure and property rights: Theory and implications for development policy. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1991, 5, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Xue, J.; Liu, Z.; Han, X.; Huang, J. China’s new rural “separating three property rights” land reform results in grassland degradation: Evidence from Inner Mongolia. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, T.; Bargh, J. The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N. The Maximum Entropy Method; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 232–237. ISBN 3642606296. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, P.; Kroese, D.; Mannor, S.; Rubinstein, R. A tutorial on the cross-entropy method. Ann. Oper. Res. 2005, 134, 19–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerken, H. The Democracy Index: Why Our Election System Is Failing and How to Fix It; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 105–109. ISBN 8158215472. [Google Scholar]

- Giannone, D. Political and ideological aspects in the measurement of democracy: The freedom house case. Democratization 2010, 17, 68–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M.; Jaggers, K. Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800−2002; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 54–68. ISBN 554-02-1652-954-8. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhanen, T. Prospects of Democracy: A Study of 172 Countries; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 66–82. ISBN 0-415-14405-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kekic, L. The economist intelligence unit’s index of democracy. Economist 2007, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, A.; Shi, T. Cultural requisites for democracy in China: Findings from a survey. Daedalus 1993, 122, 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, A. Chinese Democracy; University of California Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- He, B. Rural Democracy in China: The Role of Village Elections; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 102–156. ISBN 978-0-230-60731-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T. Rural Democracy in China; Singapore University Press: Singapore, 2000; pp. 27–52. ISBN 981-02-4288-3. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R.; Wang, N. How China Became Capitalist; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 22–40. ISBN 978-137-35143-2. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Definition | Unit | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Forestry Investment | ||||

| Forestry Labor | Cumulative household own labor force input into forestry production undertaken after Tenure Reform | Person-days | 1387.37 | 2416.84 |

| Forestry Labor, Nonlimit Households | Cumulative household own labor force input into forestry production undertaken after Tenure Reform, nonlimit households | Person-days | 1644.66 | 2191.16 |

| Forestry Production Expenditure | Cumulative monetary cost in forestry production undertaken after Tenure Reform | Ten Thousand Yuan | 5.91 | 2.67 |

| Forestry Production Expenditure, Nonlimit Households | Cumulative monetary cost in forestry production undertaken after Tenure Reform, nonlimit households | Ten Thousand Yuan | 7.01 | 2.29 |

| Property Rights | ||||

| Use Right | Use right index | / | 0.63 | 0.31 |

| Disposition Right | Disposition right index | / | 0.57 | 0.39 |

| Beneficiary Right | Beneficiary right index | / | 0.37 | 0.26 |

| Village Democracy | ||||

| Village Democracy | Village democracy index | / | 0.48 | 0.77 |

| Market Factors | ||||

| Timber Price | The available timber price for household | Yuan/m3 | 391.68 | 141.82 |

| Market Interest Rate | Annual interest rate of household borrowing money from non-financial units 1 | % | 5.64 | 0.49 |

| Wage of Forestry Labor Force | Employment wage of forestry labor force | Yuan/day | 151.61 | 31.01 |

| Social Factors | ||||

| Non-farm Income Proportion | Proportion of non-farm income to total household income | % | 43.81 | 81.94 |

| Labor Force | Number of persons in work in household | Persons | 2.79 | 0.37 |

| Education | Education level of household head | Years | 6.61 | 3.88 |

| Leadership | Family members’ experience of village leaders and cadre | 0/1 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| Ecological Factors | ||||

| Average Stand Age | Weighted average stand age of household forests | Years | 9.34 | 6.27 |

| Total Forestland Area 2 | Forestland(s) area managed by household since the Tenure Reform | Ha | 7.59 | 11.43 |

| Forestland Quality | Interviewee’s general subjective evaluation of forestland conditions and fertility | 5-point Likert Scale | 3.09 | 1.97 |

| Region | ||||

| Fujian | Whether household’s registered permanent residence is in Fujian province | 0/1 | 0.27 | 0.49 |

| Jiangxi | Whether household’s registered permanent residence is in Jiangxi province | 0/1 | 0.31 | 0.47 |

| Independent Variable | Tobit Model | Probit Model | Truncated Regression Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-Ratio | Coefficient | t-Ratio | Coefficient | t-Ratio | |

| Use Right | 539.998 ** | 1.93 | 1.008 ** | 2.58 | 4276.678 | 0.86 |

| Disposition Right | 127.036 *** | 3.42 | 0.126 *** | 3.61 | 1024.693 * | 1.83 |

| Beneficiary Right | 76.493 * | 1.68 | 0.113 ** | 2.43 | 726.980 | 1.00 |

| Village Democracy | 814.183 * | 1.76 | 0.392 | 0.54 | 13,035.940 ** | 2.13 |

| Use Right Village Democracy | 468.076 ** | 2.44 | 0.134 *** | 3.71 | 1352.707 ** | 2.21 |

| Disposition Right Village Democracy | 51.815 * | 1.75 | 0.064 | 1.14 | 742.442 * | 1.89 |

| Beneficiary Right Village Democracy | 38.507 | 0.91 | −0.006 | −0.08 | 40.293 | 0.11 |

| Timber Price | 2094.361 *** | 5.96 | 1.187 ** | 2.15 | 20,418.160 *** | 2.80 |

| Market Interest Rate | −923.616 | −0.72 | −0.545 | −0.93 | −3560.203 | −0.51 |

| Wage of Forestry Labor Force | 1.964 | 0.61 | 0.001 | 0.31 | 51.852 | 1.10 |

| Non-farm Income Proportion | −161.937 | −0.82 | 0.276 | 1.38 | −4303.782 | −1.51 |

| Labor Force | 0.829 *** | 6.24 | 0.051 *** | 6.74 | 3.269 *** | 3.32 |

| Education | 2.312 *** | 10.49 | −0.010 *** | −6.51 | 5.439 *** | 3.18 |

| Leadership | 489.906 *** | 2.60 | 0.205 | 1.10 | 7820.804 ** | 2.25 |

| Average Stand Age | 125.742 | 0.99 | 0.063 | 0.86 | 678.079 | 0.84 |

| Total Forestland Area | 5.267 * | 1.88 | 0.050 *** | 6.42 | 117.031 ** | 2.02 |

| Forestland Quality | 411.299 ** | 2.35 | 0.032 | 0.18 | 9083.495 ** | 2.31 |

| Fujian | 512.596 ** | 2.59 | 0.150 | 0.77 | 11,915.420 ** | 2.27 |

| Jiangxi | 442.618 ** | 1.99 | 0.122 | 0.53 | 12,033.360 ** | 2.21 |

| Constant | −134.817 | −0.12 | −1.086 | −0.91 | −48,555.260 ** | −1.98 |

| Statistics Diagnosis | ||||||

| Chi-squared | 371.02 | 242.86 | 24.74 | |||

| Log Lik. | −5010.98 | −158.77 | −4520.02 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.036 | 0.433 | ||||

| N | 652 | 652 | 550 | |||

| Independent Variable | Tobit Model | Probit Model | Truncated Regression Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-Ratio | Coefficient | t-Ratio | Coefficient | t-Ratio | |

| Use Right | 1.342 ** | 2.55 | 1.061 ** | 2.31 | 0.565 ** | 2.28 |

| Disposition Right | 0.306 *** | 6.04 | 0.237 *** | 3.85 | 0.062 ** | 2.32 |

| Beneficiary Right | 0.284 *** | 4.54 | 0.097 ** | 2.53 | 0.046 | 1.46 |

| Village Democracy | 2.609 *** | 4.06 | 0.843 * | 1.90 | 0.707 ** | 2.28 |

| Use Right Village Democracy | 0.334 *** | 2.73 | 0.236 *** | 3.79 | 0.077 ** | 2.36 |

| Disposition Right Village Democracy | 0.124 *** | 2.67 | 0.092 * | 1.71 | 0.039 *** | 2.75 |

| Beneficiary Right Village Democracy | 0.060 | 1.02 | 0.019 | 0.26 | 0.040 | 1.44 |

| Timber Price | 1.770 *** | 3.42 | 1.187 ** | 2.29 | 0.735 *** | 2.79 |

| Market Interest Rate | −1.454 | −1.00 | −0.648 | −0.68 | −0.324 | −0.90 |

| Wage of Forestry Labor Force | 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.003 | 0.36 | −0.0006 | −0.30 |

| Non-farm Income Proportion | 0.936 | 0.34 | 0.361 | 1.42 | −0.227 * | −1.69 |

| Labor Force | 0.0007 *** | 3.86 | 0.081 ** | 2.44 | 0.0004 *** | 4.80 |

| Education | 0.0004 | 1.40 | −0.006 ** | −2.56 | 0.0006 *** | 4.09 |

| Leadership | 0.535 ** | 2.07 | 0.304 | 1.07 | 0.338 ** | 2.58 |

| Average Stand Age | 0.183 | 0.38 | 0.091 | 0.69 | 0.063 | 1.47 |

| Total Forestland Area | 0.005 ** | 1.92 | 0.008 ** | 2.46 | 0.004 * | 1.87 |

| Forestland Quality | 0.304 | 1.26 | 0.267 | 0.85 | 0.129 | 1.08 |

| Fujian | 0.739 *** | 2.72 | 0.218 | 0.87 | 0.314 ** | 2.30 |

| Jiangxi | 0.595 | 0.94 | 0.184 | 1.53 | 0.144 | 0.94 |

| Constant | 2.123 | 1.37 | −2.948 | −1.12 | 5.307 *** | 6.79 |

| Statistics Diagnosis | ||||||

| Chi-squared | 202.07 | 219.64 | 226.36 | |||

| Log Lik. | −1447.70 | −519.29 | −894.86 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.065 | 0.206 | ||||

| N | 652 | 652 | 550 | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, Y.; Kuuluvainen, J.; Yang, L.; Yao, S.; Xue, C.; Toppinen, A. Property Rights, Village Political System, and Forestry Investment: Evidence from China’s Collective Forest Tenure Reform. Forests 2018, 9, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9090541

Ren Y, Kuuluvainen J, Yang L, Yao S, Xue C, Toppinen A. Property Rights, Village Political System, and Forestry Investment: Evidence from China’s Collective Forest Tenure Reform. Forests. 2018; 9(9):541. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9090541

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Yang, Jari Kuuluvainen, Liu Yang, Shunbo Yao, Caixia Xue, and Anne Toppinen. 2018. "Property Rights, Village Political System, and Forestry Investment: Evidence from China’s Collective Forest Tenure Reform" Forests 9, no. 9: 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9090541

APA StyleRen, Y., Kuuluvainen, J., Yang, L., Yao, S., Xue, C., & Toppinen, A. (2018). Property Rights, Village Political System, and Forestry Investment: Evidence from China’s Collective Forest Tenure Reform. Forests, 9(9), 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9090541