The Vietnamese Legal and Policy Framework for Co-Management in Special-Use Forests

Abstract

1. Introduction

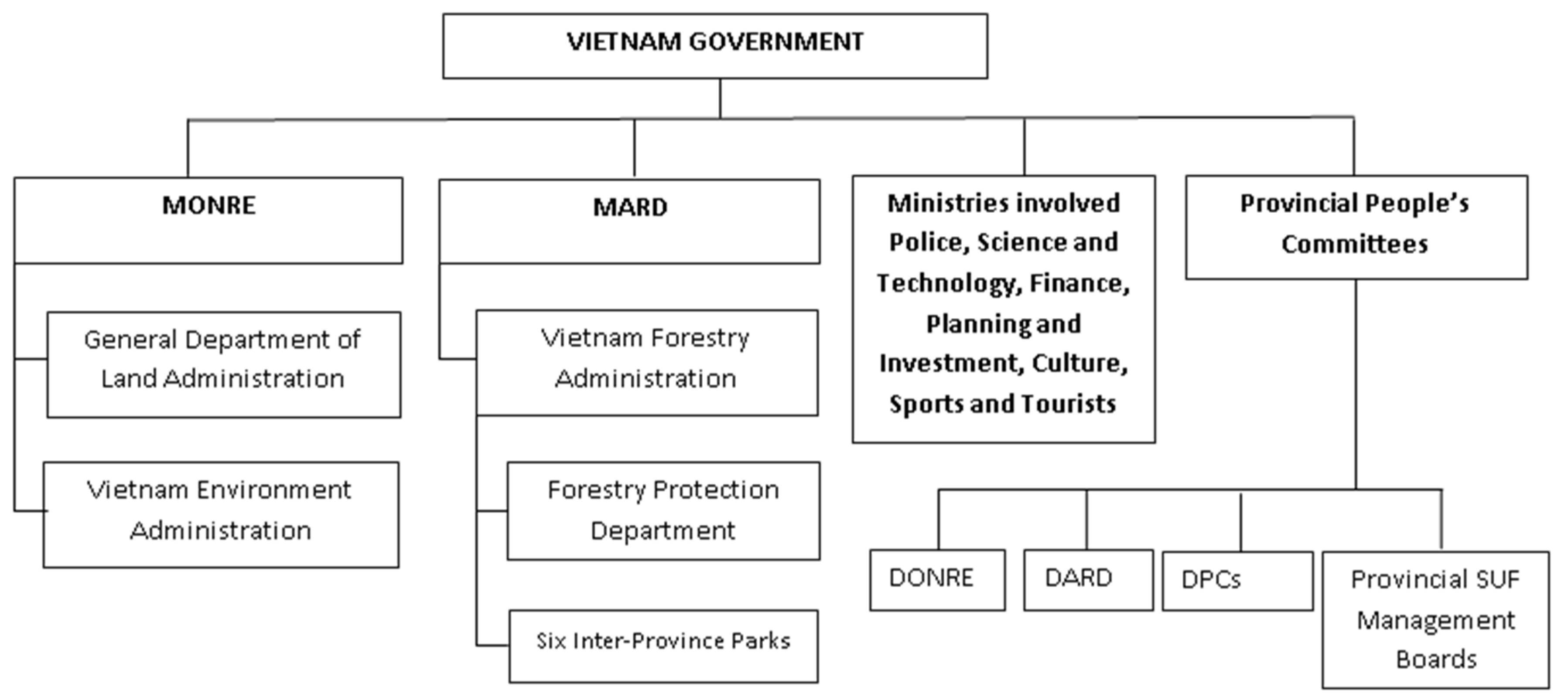

2. Policy Related Variables for Analyzing Co-Management

3. The National Legal and Policy Framework for SUF Management

4. Methodology

5. Policy Review of Co-Management

5.1. Pluralism and Legitimate Participation

5.2. Communication and Negotiation

5.3. Transactive Decision-Making

5.4. Social Learning

5.5. Shared Actions and Commitments

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Actors | Responsibilities and Authorities | Legal Document Mentioned |

|---|---|---|

| Central Level | ||

| Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development |

| Law on Fisheries 2003; Decree 109/2003/ND-CP; Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg; Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Decision 62/2005/QD-BNN; Decision 1174/2005/QD-TTg; Decision 106/2006/QD-BNN; Circular 70/2007/TT-BNN; Decision 104/2007/QD-BNN; Decision 2740/2007/QD-BNN-KL; Circular 22/2007/TTLT-BNN-BNV; Decision 2370/2008/QD-BNN-KL; Decree 99/2010/ND-CP; Decree 117/2010/ND-CP; Decision 262/2010/QD-TCLN-KL; Circular 78/2011/TT-BNNPTNT |

| Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment |

| Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg; Circular 18/2004/TT-BTNMT; Decree 109/2003/ND-CP; Decision 1174/2005/QD-TTg; Decision 04/2004/QD-BTNMT |

| Ministry of Police |

| Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004 |

| Ministry of National Defense |

| Law on Forest Protection and Development (2004); Direction 45/2007/CT-BNN; Circular 98/2010/TTLT-BQP-BNNPTNT; Decree 74/2010/ND-CP; Decision 07/2012/QD-TTg |

| Ministry of Culture and Information |

| Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Decision 04/2004/QD-BTNMT; Decision 104/2007/QD-BNN; Direction 24/1998/CT-TTg; Decision 08/2001/QD-TTg |

| Ministry of Planning and Investment |

| Decision 08/2001/QD-TTg; Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg; Decision 1174/2005/QD-TTg; Decree 117/2010/ND-CP; Decision 07/2012/QD-TTg; Decision 24/2012/QD-TTg; Decision 1250/2013/QD-TTg; Decision 218/2014/QD-TTg; Decision 1976/2014/QD-TTg |

| Ministry of Finance |

| Decree 119/2006/ND-CP; Circular 25/2006/TT-BTC; Decree 05/2008/ND-CP; Circular 01/2008/TT-BTC; Cicular 58/2008/TTLT-BNN-KHDT-TC; Decision 2370/2008/QD-BNN-KL; Decision 24/2012/QD-TTg; Decision 07/2012/QD-TTg; Decision 218/2014/QD-TTg; Decision 1976/2014/QD-TTg |

| Ministry of Science and Technology |

| Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg |

| Ministry of Education and Training |

| Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg |

| Provincial Level | ||

| PPCs |

| Direction 24/1998/CT-TTg; Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Circular 18/2004/TT-BTNMT; Decision 1174/2005/QD-TTg; Decision 2740/2007/QD-BNN-KL; Decree 99/2010/ND-CP; Decree 12/2012/ND-CP; Article 137 Land Law 2013 |

| DARD |

| Decision 106/2006/QD-BNN; Circular 70/2007/TT-BN; Decree 99/2010/ND-CP; Decree 117/2010/ND-CP; Circular 78/2011/TT-BNNPTNT |

| DONRE |

| Decree 109/2003/ND-CP; Circular 78/2011/TT-BNNPTNT |

| Department of Forest Protection |

| Decree 119/2006/ND-CP; Decision 1717/2006/QD-BNN-KL; Circular 70/2007/TT-BNN; Circular 22/2007/TTLT-BNN-BNV; Direction 45/2007/CT-BNN; Circular 61/2007/TTLT-BNN-BTC |

| Department of Planning and Investment |

| Circular 58/2008/BNN-KHDT-BTC |

| Department of Finance |

| Circular 58/2008/BNN-KHDT-TC |

| District Level | ||

| DPCs |

| Direction 30/1998/CT-TW; Decision 08/2001/QD-TTg; Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Decision 1174/2005/QD-TTg; Decision 106/2006/QD-BNN; Decree 119/2006/ND-CP; Decision 1717/2006/QD-BNN-KL; Circular 70/2007/TT-BNN; Circular 22/2007/TTLT-BNN-KL; Decree 117/2010/ND-CP; Decree 99/2010/ND-CP |

| CPCs |

| Direction 24/1998/CT-TTg;Decision 08/2001/QD-TTg; Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg; Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Decision 1174/2005/QD-TTg; Decree 119/2006/ND-CP; Decision 1717/2006/QD-BNN-KL; Decision 104/2007/QD-BNN; Ordinance 34/2007/PL-UBTVQH11; Decree 99/2010/ND-CP; Decree 117/2010/ND-CP; Direction 3714/2011/CT-BNN-TCLN; Decision 57/2012/QD-TTg; Decision 126/2012/QD-TTg |

| SUF management boards |

| Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg; Circular 18/2004/TT-BTNMT; Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Decision 104/2007/QD-BNN; Circular 01/2008/TT-BTC; Circular 58/2008/TTLT-BNN-KHDT-TC; Decision 262/2010/QD-TCLN-KL; Circular 78/2011/TT-BNNPTNT; Decree 117/2010/ND-CP; Decision 24/2012/QD-TTg; Decision 126/2012/QD-TTg |

| Economic organisations |

| Decision 08/2001/QD-TTg; Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Circular 58/2008/TTLT-BNN-KHDT-TC; Decree 99/2010/ND-CP; Circular 80/2011/TT-BNNPTNT; Decision 07/2012/QD-TTg; Decision 57/2012/QD-TTg |

| Governmental mass organisations |

| Direction 30/1998/CT-TW; Direction 24/1998/CT-TTg; Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg; Decision 04/2004/QD-BTNMT; Law on Inspection 2010 (Article 12); Circular 78/2011/TT-BNNPTNT |

| International organisations |

| Decree 12/2012/ND-CP; Decision 40/2013/QD-TTg |

| Local people |

| Decision 08/2001/QD-TTg; Decision 192/2003/QD-TTg; Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Circular 18/2004/TT-BTNMT; Decision 62/2005/QD-BNN; Decision 1174/2005/QD-TTg; Circular 78/2011/TT-BNNPTNT; Decision 57/2012/QD-TTg |

References

- Protected Areas for Resources Conservation (PARC) Project. Policy brief: Building Vietnam’s National Protected Areas System: Policy and Institutional Innovations Required for Progress. In Creating Protected Areas for Resource Conservation Using Landscape Ecology; Project VIE/95/G31&031; Government of Vietnam (FPD); UNOPS; UNDP; IUCN: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment. 2010 Vietnam Environmental Report: Overview of Vietnam Environment; Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011.

- Vietnam Government. The Prime Minister on Issuing Regulations on the Management of Special-Use Forests, Environmental Forests, and Natural Productive Forests; Decision No. 08/2001/QD-TTg; Government of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2001.

- PanNature. Handbook: Skills for Enhancing Community Participation in Forest Management; Hong Duc Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Meyfroidt, P.; Lambin, E.F. Forest transition in Vietnam and its environmental impacts. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 14, 1319–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, E.S.; Harwood, C.E.; Kien, N.D. Acacia plantations in Vietnam: Research and knowledge application to secure a sustainable future. South. For. J. For. Sci. 2015, 77, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cuong, T.N.; Dung, N.X.; Trang, T.H.; Minh, P.B.; Le, P.Q. Some Contents of Vietnamese Biodiversity Management; Department of Biodiversity Conservation: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2009.

- Zingerli, C. Colliding Understandings of Biodiversity Conservation in Vietnam: Global Claims, National Interests, and Local Struggles. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P. Resource use among rural agricultural households near protected areas in Vietnam: The social cost of conservation and implications for enforcement. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sam, D.D.; Trung, L.Q. Forest Policy Trends in Vietnam. Policy Trend Rep. 2001, 69–73. Available online: https://pub.iges.or.jp/pub/policy-trend-report-2001 (accessed on 7 December 2014).

- Tan, N.Q.; Chinh, N.V.; Hanh, V.T. Evaluating Policy Barriers Impacting on Sustainable Forest Management and Equity: A Case Study in Vietnam; IUCN: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2008; pp. 6–35. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, R. The adaptive co-management process: An initial synthesis of representative models and influential variables. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Nielsen, J.R. Fisheries co-management: A comparative analysis. Mar. Policy 1996, 20, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, C.A. Mono-organizational socialism and the state. In Vietnam’s Rural Transformation; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, T.P. Fisheries co-management in Vietnam: Issues and approach. Proceedings of 14th Biennial Conference of the International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade Conference (IIFET 2008): Achieving a Sustainable Future: Managing Aquaculture, Fishing, Trade and Development, Nha Trang, Vietnam, 22–25 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, J.; Gronow, J. Recent Experience in Collaborative Forest Management—A Review Paper; CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 43; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- KimDung, N.; Bush, S.R.; Mol, A.P. NGOs as Bridging Organizations in Managing Nature Protection in Vietnam. J. Environ. Dev. 2016, 25, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KimDung, N.; Bush, S.; Mol, A.P. Administrative co-management: The case of special-use forest conservation in Vietnam. Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomeroy, R. Community-based and co-management institutions for sustainable coastal fisheries management in Southeast Asia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 1995, 27, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S. Fisheries Co-Management Research and the Case Study Method. Presented at the International Workshop on Fisheries Co-management, Penang, Malaysia, 23–28 August 1999; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, L.; Berkes, F. Co-management: Concepts and methodological implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 75, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Berkes, F. Adaptive Comanagement for Building Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems. Environ. Manag. 2004, 34, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBeath, J.; Rosenberg, J. Advances in Global Change Research: Comparative Environmental Politics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.R.A.; Young, J.C.; McMyn, I.A.G.; Leyshon, B.; Graham, I.M.; Walker, I.; Baxter, J.M.; Dodd, J.; Warburton, C. Evaluating adaptive co-management as conservation conflict resolution: Learning from seals and salmon. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 160, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, P.R.; Foley, K.; Collier, M.J. Operationalizing urban resilience through a framework for adaptive co-management and design: Five experiments in urban planning practice and policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, M.; Berkes, F. Towards adaptive co-management of small-scale fisheries in Uruguay and Brazil: Lessons from using Ostrom’s design principles. Mar. Stud. 2015, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.R.; Plummer, R.; Berkes, F.; Arthur, R.I.; Charles, A.T.; Davidson-Hunt, I.J.; Diduck, A.P.; Doubleday, N.C.; Johnson, D.S.; Marschke, M. Adaptive co-management for social-ecological complexity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 7, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Galaz, V.; Hahn, T.; Schultz, L. Enhancing the fit through adaptive co-management: Creating and maintaining bridging functions for matching scales in the Kristianstads Vattenrike Biosphere Reserve, Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S.L.; Loe, R.C.D. The Changing Role of ENGOs in Water Governance: Institutional Entrepreneurs? Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigby, T.H. Introduction: Political legitimacy, Weber and communist mono-organisational systems. In Political Legitimation in Communist States; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1982; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sikor, T.; Nguyen, T.Q. Why may forest devolution not benefit the rural poor? Forest entitlements in Vietnam’s central highlands. World Dev. 2007, 35, 2010–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Baird, J.; Dzyundzyak, A.; Armitage, D.; Bodin, Ö.; Schultz, L. Is Adaptive Co-management Delivering? Examining Relationships Between Collaboration, Learning and Outcomes in UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Fitzgibbon, J. Co-management of Natural Resources: A Proposed Framework. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Armitage, D.; de Loë, R. Adaptive comanagement and its relationship to environmental governance. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Wakjira, D.T.; Weldesemaet, Y.T.; Ashenafi, Z.T. On the interplay of actors in the co-management of natural resources—A dynamic perspective. World Dev. 2014, 64, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Lassoie, J.; Shrestha, K.; Yan, Z.; Sharma, E.; Pariya, D. Institutional development for sustainable rangeland resource and ecosystem management in mountainous areas of northern Nepal. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USAID’s Coral Triangle Support Partnership. Guidelines for Establishing Co-Management of Natural Resources in Timor-Leste; Conservation International for the Timor-Leste National Coordinating Committee: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner, E.M.; Basurto, X. Re-defining co-management to facilitate small-scale fisheries reform: An illustration from northwest Mexico. Mar. Policy 2015, 51, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J. Decentralization and devolution in forest management: A conceptual overview. In Decentralization and Devolution of Forest Management in Asia and the Pacific; RECOFTC Report No. 18; FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkog, Thailand, 2000; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, T.K.P.; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; Arts, B. The Institutional Capacity for Forest Devolution: The Case of Forest Land Allocation in Vietnam. Dev. Policy Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Devolution of environment and resources governance: Trends and future. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Sendzimir, J.; Jeffrey, P.; Aerts, J.; Berkamp, G.; Cross, K. Managing change toward adaptive water management through social learning. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkerton, E.W. Local Fisheries Co-management: A Review of International Experiences and Their Implications for Salmon Management in British Columbia. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1994, 51, 2363–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfadyen, G.; Cacaud, P.; Kuemlangan, B. Policy and legislative frameworks for co-management. In Proceedings of the APFIC Regional Workshop on Mainstreaming Fisheries Co-Management in Asia Pacific, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 9–12 August 2005; FAO/FishCode Review. No.17. Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2005; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Jentoft, S. The community: A missing link of fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2000, 24, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, R.I. Developing, Implementing and Evaluating Policies to Support Fisheries Co-Management; MRAG: London, UK, 2005; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, R.; Berkes, F. Two to tango: The role of government in fisheries co-management. Mar. Policy 1997, 21, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoan, D.T. Thách thức triển khai các sáng kiến mới trong ngành lâm nghiệp. Policy News PanNature 2014, 15, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Van, N.H. Nghiên cứu về chồng lấn quyền sử dụng đất rừng đặc dụng. Policy News PanNature 2014, 15, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, D.H. Giám sát môi trường của các cơ quan dân cử: Có giám mà không sát. Policy News PanNature 2015, 17, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Trædal, L.T.; Vedeld, P.O.; Pétursson, J.G. Analyzing the transformations of forest PES in Vietnam: Implications for REDD+. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Larson, A.M.; Duchelle, A.E.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Huynh, T.B.; Awono, A.; Dokken, T. How are REDD+ proponents addressing tenure problems? Evidence from Brazil, Cameroon, Tanzania, Indonesia, and Vietnam. World Dev. 2014, 55, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinyopusarerk, K.; Tran, T.T.H.; Tran, V.D. Making community forest management work in northern Vietnam by pioneering participatory action. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diem, D. Sắp xếp, đổi mới nông lâm trường: Đôi điều cần làm. Policy News PanNature 2014, 15, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Phuc, T.X. Quản lý lâm nghiệp nhìn từ quy hoạch và thị trường. Policy News PanNature 2014, 15, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Suhardiman, D.; Wichelns, D.; Lestrelin, G.; Hoanh, C.T. Payments for ecosystem services in Vietnam: Market-based incentives or state control of resources? Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 6, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolinjivadi, V.; Sunderland, T. A review of two payment schemes for watershed services from China and Vietnam: The interface of government control and PES theory. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, P.X.; Dressler, W.H.; Mahanty, S.; Pham, T.T.; Zingerli, C. The prospects for payment for ecosystem services (PES) in Vietnam: A look at three payment schemes. Hum. Ecol. 2012, 40, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuan, V.T.B. Evaluation of stakeholder participation in Special-use forest management in West North Vietnam. For. Sci. 2015, 1, 3717–3726. [Google Scholar]

- Van, H.N.; Dung, N.V. Overlapping Rights of Special-Use Forest Landuse: Challenges for Master Plans and Special-Use Forest Management in Vietnam; Hong Duc Publication House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Phuong, N.M. The status quo of local decentralization and devolution in Vietnam. Proceedings of The Organization of Local Governments in Vietnam: Issues of Concepts and Practices, Ninh Thuan, Vietnam, 6 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Operational Question |

|---|---|

| 1. Social learning |

|

| |

| |

| 2. Pluralism |

|

| |

| |

| |

| 3. Transactive Decision-making |

|

| |

| 4. Communication and Negotiation |

|

| |

| |

| 5. Shared Actions and Commitments |

|

|

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

KimDung, N.; Bush, S.R.; Mol, A.P.J. The Vietnamese Legal and Policy Framework for Co-Management in Special-Use Forests. Forests 2017, 8, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8070262

KimDung N, Bush SR, Mol APJ. The Vietnamese Legal and Policy Framework for Co-Management in Special-Use Forests. Forests. 2017; 8(7):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8070262

Chicago/Turabian StyleKimDung, Nguyen, Simon R. Bush, and Arthur P. J. Mol. 2017. "The Vietnamese Legal and Policy Framework for Co-Management in Special-Use Forests" Forests 8, no. 7: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8070262

APA StyleKimDung, N., Bush, S. R., & Mol, A. P. J. (2017). The Vietnamese Legal and Policy Framework for Co-Management in Special-Use Forests. Forests, 8(7), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8070262