Understanding the Factors Influencing Nonindustrial Private Forest Landowner Interest in Supplying Ecosystem Services in Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

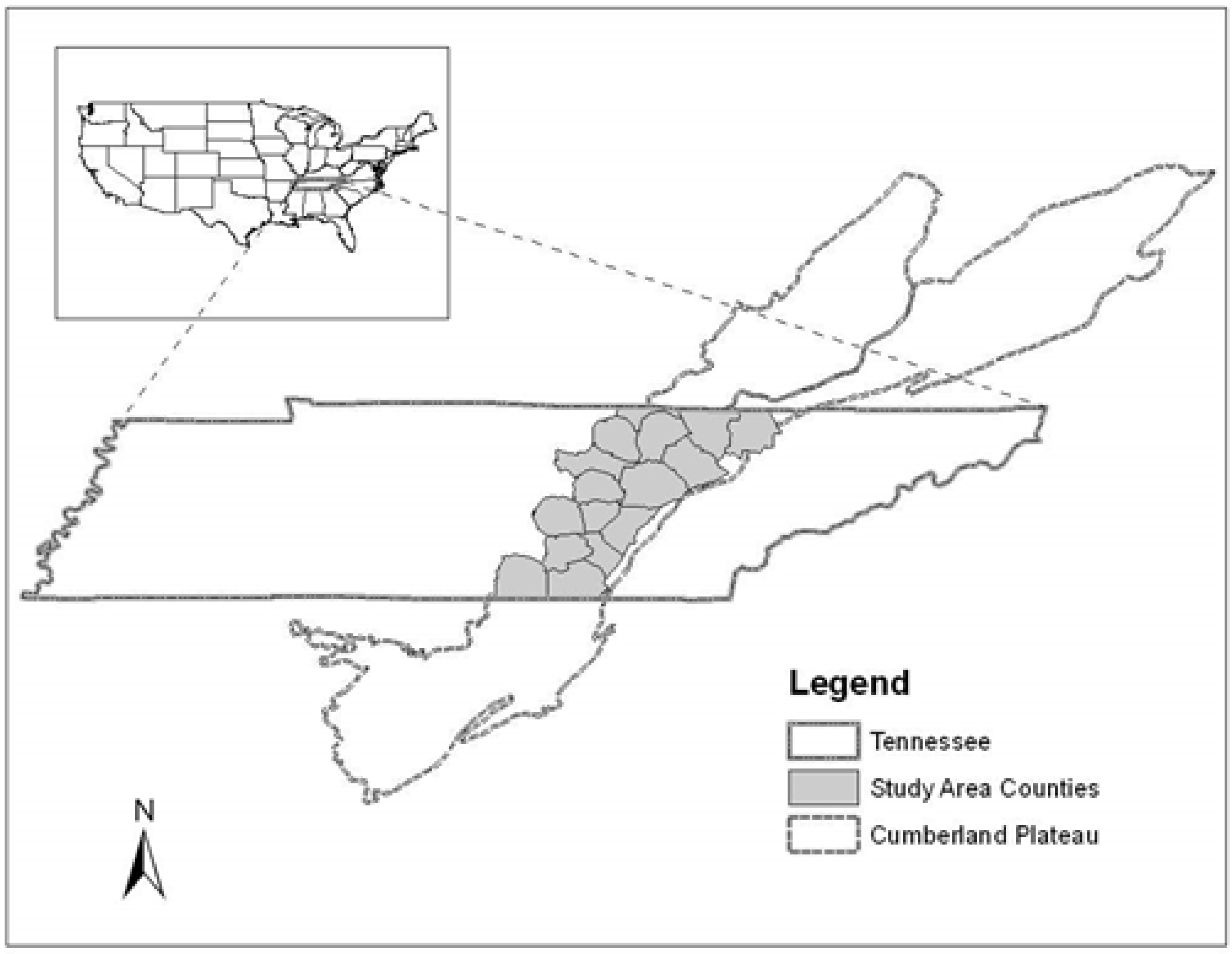

3.1. Study Area and Data Collection

| Variable | Description | Mean (S.E.) |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Age | Age of the landowner | 68.99 (12.63) |

| Female | Dummy variable, 1 if female, 0 otherwise | 0.23 (0.42) |

| Education | Dummy variable, 1 if landowner has more than college education, 0 otherwise | 0.39 (0.49) |

| Income | Dummy variable, 1 if landowner has >$75,000 in annual income, 0 otherwise | 0.34 (0.47) |

| Occupation | Dummy variable, 1 if white-collar occupation, 0 otherwise | 0.17 (0.38) |

| Forest ownership and management objective | ||

| Tenure | Number of years the property has been with landowner’s family | 43.06 (41.92) |

| Acquisition | The mode of acquisition of forest by landowners. (1 if purchased, 0 otherwise) | 0.72 (0.45) |

| Ownership size | Categorical variable, 1 if the landowner owns <10 acres of forestland, 2 if owns between 10 and 100 acres, and 3 if owns >100 acres | 2.22 (0.49) |

| Timber harvesting | Dummy variable, 1 if the landowner recently harvested timber or planning to harvest soon, 0 otherwise | 0.22 (0.41) |

| Advice | Dummy variable, 1 if the landowner received advice from professionals, 0 otherwise | 0.04 (0.19) |

| Attitudes toward Incentives | ||

| Property tax | Reported usefulness of property tax as incentive (1 = not useful, 5 = extremely useful) | 3.65 (1.27) |

| Payment of individuals/companies | Reported usefulness of payment from private individual/company as incentive (1 = not useful, 5 = extremely useful) | 2.85 (1.50) |

| Payment of government | Reported usefulness of payments from government as incentive (1 = not useful, 5 = extremely useful) | 3.05 (1.49) |

| Motivations of owning forestlands | ||

| Financial investment | Importance placed by landowner on “financial investment” as ownership motivation (1 = not important, 5 = extremely important) | 3.03 (1.36) |

| Hunting/fishing | Importance placed by landowner on “hunting and fishing” as ownership motivation (1 = not important, 5 = extremely important) | 2.71 (1.48) |

| Farm/Home site | Importance placed by landowner on “farm” as ownership motivation (1 = not important, 5 = extremely important) | 3.53 (1.45) |

| Inheritance | Importance placed by landowner on “pass on to heirs” as ownership motivation (1 = not important, 5 = extremely important) | 2.46 (1.67) |

| Peacefulness/tranquility | Importance placed by landowner on “peacefulness and tranquility” as ownership motivation (1 = not important, 5 = extremely important) | 3.94 (1.20) |

| Future ownership plan | ||

| Inherit | Dummy variable, 1 if landowner plans to pass the forests to heirs, 0 otherwise | 0.76 (0.43) |

| Develop | Dummy variable, 1 if landowner continues to manage the forests, 0 otherwise | 0.06 (0.24) |

| Sell | Dummy variable, 1 if landowner plans to sell the forests, 0 otherwise | 0.19 (0.40) |

| Donate | Dummy variable, 1 if landowner plans to donate the forests to others, 0 otherwise | 0.03 (0.17) |

| Other factors | ||

| Perceived risk of damage | Landowner’s perception of risks of environmental damage associated with harvesting timber (1 = no risk at all, 5 = extreme risk) | 3.34 (0.91) |

| Return from forest | Land productivity from forest use as measured by per acre value ($) of timber products for landowner’s county | 10.51 (3.87) |

3.2. Empirical Model

4. Results

| Ecosystem Services | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Carbon | Water | Aesthetics | VIF |

| Coefficient (S.E.) | Coefficient (S.E.) | Coefficient (S.E.) | ||

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age | 0.03 (0.01) *** | 0.03 (0.01) ** | 0.03 (0.01) *** | 1.42 |

| Gender | 0.76 (0.31) ** | 0.80 (0.36) ** | 0.40 (0.33) | 1.39 |

| Education | −0.35 (0.25) | 0.01 (0.29) | 0.0007 (0.1) | 1.38 |

| Income | −0.29 (0.25) | 0.07 (0.28) | 0.52 (0.27) * | 1.33 |

| Occupation | −0.89 (0.33) *** | −0.09 (0.37) | 0.005 (0.35) | 1.66 |

| Forest ownership and management objectives | ||||

| Tenure | 0.02 (0.00) *** | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.007 (0.00) * | 2.01 |

| Acquisition | 0.36 (0.35) | −0.10 (0.39) | 0.17 (0.36) | 2.32 |

| Ownership size | −0.24 (0.27) | 0.27 (0.30) | 0.02 (0.28) | 1.32 |

| Timber harvesting | 0.04 (0.27) | 0.54 (0.31) * | −0.33 (0.29) | 1.23 |

| Advice | 0.63 (0.63) | −0.04 (0.69) | 0.89 (0.67) | 1.23 |

| Attitudes toward Incentives | ||||

| Tax property | −0.12 (0.13) | 0.25 (0.14) * | 0.40 (0.14) *** | 2.18 |

| Payment of individuals/companies | −0.07 (0.12) | 0.11 (0.14) | 0.09 (0.12) | 2.82 |

| Payment of government | 0.51 (0.14) *** | 0.08 (0.14) | −0.14 (0.13) | 2.75 |

| Motivations of owning Forestlands | ||||

| Financial investment | 0.03 (0.09) | −0.19 (0.10) * | −0.09 (0.10) | 1.34 |

| Hunting/fishing | 0.05 (0.09) | 0.25 (0.10) *** | −0.05 (0.09) | 1.38 |

| Farm/home site | −0.14 (0.10) | −0.06 (0.11) | −0.18 (0.10) * | 1.64 |

| Inheritance | −0.10 (0.09) | −0.10 (0.12) | 0.04 (0.11) | 2.54 |

| Peacefulness/tranquility | 0.58 (0.12) *** | 0.46 (0.13) *** | 0.61 (0.12) *** | 1.53 |

| Future ownership plan | ||||

| Inherit | −0.71 (0.31) ** | −0.18 (0.32) | −0.12 (0.31) | 1.41 |

| Develop | 0.20 (0.48) | −0.21 (0.55) | 0.37 (0.54) | 1.11 |

| Sell | −0.73 (0.32) ** | −0.17 (0.35) | 0.08 (0.32) | 1.50 |

| Donate | −0.73 (0.65) | −0.50 (0.73) | −0.88 (0.71) | 1.18 |

| Other factors | ||||

| Perceived risk of damage | 0.83 (0.30) *** | 0.65 (0.18) *** | 0.38 (0.20) * | 3.15 |

| Return from forest | 0.003 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.03) * | 1.21 |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being. A Framework for Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-BEING. A Framework for Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, B.J.; Leatherberry, E.C. America’s family forest owners. J. For. 2004, 102, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Blatner, K.A.; Baumgartner, D.M.; Quackenbush, L.R. NIPF use of landowner assistance and education programs in Washington State. West. J. Appl. For. 1991, 6, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wear, D.N.; Greis, J.G. The Southern Forest Resource Assessment Summary Report; General Techical Report SRS-54; USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2002; p. 103.

- Oswalt, C.M.; Oswalt, S.N.; Johnson, T.G.; Brandeis, C.; Randolph, K.C.; King, C.R. Tennessee’s Forests, 2009; Resources Bulletin. RB-SRS-189; USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA; p. 136.

- Pattanayak, S.; Murray, B.; Abt, R. How joint is joint forest production? An econometric analysis of timber supply conditional on endogenous amenity values. For. Sci. 2002, 47, 479–491. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, I.; Teeter, L.; Butler, B. Characterizing family forest owners: A cluster analysis approach. For. Sci. 2008, 54, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, O.; Brunson, M.; Kuhns, M. Benefit-based audience segmentation: A tool for identifying nonindustrial private forest (NIPF) owner education needs. J. For. 2006, 104, 419–425. [Google Scholar]

- Berta, M.L.; Irene, I.A.; Marina, G.L. Uncovering Ecosystem Service Bundles through Social Preferences. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Elwood, N.E.; Hansen, E.N.; Oester, P. Management plans and Oregon’s NIPF owners: A survey of attitudes and practices. West. J. Appl. For. 2003, 18, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, D.L.; Ryan, R.L.; Young, R.D. Woodlots in the rural landscape: Landowner motivations and management attitudes in a Michigan (USA) case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 58, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Arano, K.G. Determinants of private forest management decisions: A study on West Virginia NIPF landowners. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoot, T.G.; Rickenbach, M.; Silbernagel, K. Payments for ecosystem services: Will a new hook net more active family forest owners? J. For. 2015, 113, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorice, M.G.; Kreuter, U.P.; Wilcox, B.P.; Fox, W.E., III. Changing landowners, changing ecosystem? Land-ownership motivations as drivers of land management practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 133, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.W.; Hansen, E.N. Carbon storage on Non-industrial private forestland: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Small-Scale For. 2013, 12, 631–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.W.; Hansen, E.N. Factors affecting the attitudes of nonindustrial private forest landowners regarding carbon sequestration and trading. J. For. 2012, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, M.C.; Amacher, G.S.; Sullivan, J. Decisions nonindustrial forest landowners make: An empirical examination. J. For. Econ. 2003, 9, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, A.O.; Kittredge, D.B., Jr. Thoreau, Muir, and Jane Doe: Different types of private forest owners need different kinds of forest management. North. J. Appl. For. 2006, 23, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Karppinen, H. Values and objectives of non-industrial private forest owners in Finland. Silva Fenn. 1998, 32, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaetzel, B.R.; Hodges, D.G.; Houston, D.; Fly, J.M. Predicting the probability of landowner participation in conservation assistance programs: A case study of the Northern Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee. South. J. Appl. For. 2009, 33, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kuuluvainen, J.; Karppinen, H.; Ovaskainen, V. Landowner objectives and nonindustrial private timber supply. For. Sci. 1996, 42, 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Nagubandi, V.; McNamara, K.T.; Hoover, W.L. Program participation behavior of nonindustrial forest landowners: A probit analysis. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1996, 28, 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf, K.A.; Ross-Davis, A.L.; Broussard, S.R. Exploring the dimensionality and social bases of the public’s timber harvesting attitudes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornqvist, T. Inheritors of the woodlands. In A Sociological Study of Private, Nonindustrial Forest Ownership; Rapport-Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet; Institution for Skog-Industri-Marknad Studier: Almas, Sweden, 1995; Volume 41, pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Binkley, C.S. Timber Supply from Private Nonindustrial Forests: A Microeconomic Analysis of Landowner Behavior; Bulletin No. 92; Yale University, School of Forestry and Environmental Studies: New Haven, CT, USA, 1981; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Kilgore, M.A.; Snyder, S.A.; SCHERTZ, J.; Taff, S.J. What does it take to get family forest owners to enroll in a forest stewardship type program? For. Policy Econ. 2008, 10, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardner, J.J.; Frumhoff, P.C.; Goetze, D. Prospects for mitigating carbon, conserving biodiversity, and promoting socioeconomic development objectives through the clean development mechanism. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2000, 5, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, R.L.; Thompson, B.H.; Daily, G.C. Institutional incentives for managing the landscape: Including cooperation for the production of ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 64, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, J.B.; Kousky, C.; Sims, K.R.E. Designing payments for ecosystem services: Lessons from previous experience with incentive-based mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9465–9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amacher, G.S.; Conway, M.C.; Sullivan, J. Econometric analyses of nonindustrial forest landowners: Is there anything left to study? J. For. Econ. 2003, 9, 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hyberg, B.; Holthausen, D. The behavior of non-industrial private forest landowners. Can. J. For. Res. 1989, 19, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max, W.; Lehman, D. A behavioral model of timber supply. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1988, 15, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany; Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Leitch, Z.J.; Lhotkam, J.M.; Stainback, G.A.; Stringer, J.W. Private landowner intent to supply woody feedstock for bioenergy production. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 56, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nature Conservancy. Tennessee: Protecting America’s Most Biologically Rich Inland. Available online: http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/tennessee/index.htm (accessed on 29 June 2013).

- Hoyt, K.P. A Socioeconomic Study of the Non-Industrial Private Forest Landowner Wood Supply Chain Link in the Cumberland Plateau Region of Tennessee. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal, N.C.; Joshi, O.; Hodges, D.G.; Hoyt, K. Factors Related with Nonindustrial Private Forest Landowners’ Forest Conversion Decision in Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arano, K.G.; Munn, I.A.; Gunter, J.E.; Bullard, S.H. Comparison between regenerators and Non-regenerators in Mississippi: A discriminant analysis. South. J. Appl. For. 2004, 28, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, D.R.; Eryilmaz, D.; Klapperich, J.; Kilgore, M.A. Social availability of residual woody biomass from nonindustrial private woodland owners in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 56, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, O.; Mehmood, S.R. Factors influencing NIPF landowners’ willingness to supply woody biomass. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.; Wang, Y.; Guess, F. Understanding the characteristics of non-industrial private forest landowners who harvest trees. Small-Scale For. 2015, 14, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, J.; Alig, R.J.; Johnson, R.L. Fostering the production of nontimber services among forest owners with heterogeneous objectives. For. Sci. 2000, 46, 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Van Herzele, A.; van Gossum, P. Owner-specific factors associated with conversion activity in secondary pine plantations. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, R.H.; Anderson, N.; Bevilacqua, E. The effects of forestland parcelization and ownership transfers on nonindustrial private forestland forest stocking in New York. J. For. 2007, 105, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Mendham, E.; Curtis, A. Taking over the reins: Trends and impacts of changes in rural property ownership. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M. Factors affecting private forest landowner interest in ecosystem management: Linking spatial and survey data. Environ. Manag. 2002, 30, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendra, A.; Hull, R.B. Motivations and behaviors of new forest owners in Virginia. For. Sci. 2005, 51, 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J.F.; Spies, T.A.; Pelt, R.V. Disturbances and structural development of natural forest ecosystems with silvicultural implications, using Douglas-fir forests as an example. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 155, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, C. The Ricardian rent theory: An overview. In Centro Sraffa Working Papers; University of Paris Ouest: Nanterre, French, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, R.; Green, G.; Poudyal, N.; Cordell, H.K. Do outdoor recreation participates place their lands in conservation easements? Nat. Conserv. 2014, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackerron, G.J.; Egerton, C.; Gaskell, C.; Parpia, A.; Mourato, S. Willingness to pay for carbon offset certification and co-benefits among (high-) flying young adults in the UK. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcfarlane, B.L.; Hunt, L.M. Environmental activism in the forest sector: Social psychological, social-cultural, and contextual effects. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 266–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindall, D.B.; Davies, S.; Mauboules, C. Activism and conservation behavior in an environmental movement: The contradictory effects of gender. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 909–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Snyder, S.A.; Kilgore, M.A. An assessment of forest landowner interest in selling forest carbon credits in the Lake States, USA. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 25, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, J.C.; Lavallato, S.; Cherry, M.; Hileman, E. Land use determines interest in conservation easements among private landowners. Land Use Policy 2013, 35, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickenson, B.J. Massachusetts Landowner Participation in Forest Management Programs for Carbon Sequestration: An Ordered Logit Analysis of Ratings Data. Master’s Thesis, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, T.R.H.; Brown, S.; Andrasko, K. Comparison of registry methodologies for reporting carbon benefits for afforestation projects in the United States. Environ. Sci. Policy 2008, 11, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, N.; Poudyal, N.C.; Hodges, D.G.; Young, T.M.; Hoyt, K.P. Understanding the Factors Influencing Nonindustrial Private Forest Landowner Interest in Supplying Ecosystem Services in Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee. Forests 2015, 6, 3985-4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/f6113985

Tian N, Poudyal NC, Hodges DG, Young TM, Hoyt KP. Understanding the Factors Influencing Nonindustrial Private Forest Landowner Interest in Supplying Ecosystem Services in Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee. Forests. 2015; 6(11):3985-4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/f6113985

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Nana, Neelam C. Poudyal, Donald G. Hodges, Timothy M. Young, and Kevin P. Hoyt. 2015. "Understanding the Factors Influencing Nonindustrial Private Forest Landowner Interest in Supplying Ecosystem Services in Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee" Forests 6, no. 11: 3985-4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/f6113985

APA StyleTian, N., Poudyal, N. C., Hodges, D. G., Young, T. M., & Hoyt, K. P. (2015). Understanding the Factors Influencing Nonindustrial Private Forest Landowner Interest in Supplying Ecosystem Services in Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee. Forests, 6(11), 3985-4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/f6113985