1. Introduction

Currently, humanity is actively seeking effective measures to mitigate the potential impacts of climate change on human living environments. It is widely recognized that forestry development influences global climate patterns, while climate change, in turn, affects the ways in which forest resources are managed [

1]. Moreover, forestry development can create employment opportunities and play a positive role in promoting economic stability [

2]. Since 2003, China has been advancing its collective forest tenure reform, which has significantly contributed to the rapid expansion of its forest resources. According to statistics from relevant institutions, China experienced rapid average annual acceleration in the growth rate of the forest coverage area during the period from 2000 to 2010, surpassing the levels recorded in both 1990–2000 and 2010–2020 [

3]. One of the key reasons for the success of the collective forest tenure reform lies in the implementation of household-based decentralization measures. Most households gained long-term contract rights to manage collectively owned forestland, with clearly defined plot boundaries. These improvements in tenure security have contributed to both better forest environmental outcomes and enhanced household welfare [

4]. Stable property rights enable forest owners to exercise their corresponding rights based on their endowments, thus improving forestland productivity. However, the implementation of household-based tenure decentralization has concurrently induced challenges, including excessive forestland fragmentation and constrained scale effects. As fragmented plots fail to generate sufficient economic returns and exhibit low production efficiency and high operational difficulty [

5], an increasing number of forest-dependent households are turning to non-agricultural employment as a supplement or even a substitute for forest management. This shift has led to a decline in management quality due to reduced labor input. Moreover, the fragmented nature of forestland further hampers improvements in forestry management, widening the productivity gap between forestry and other sectors.

In this context, enhancing the level of forestry management has become a central concern. Scale management is widely recognized as an effective approach to reduce the unit production costs, improve the labor and capital efficiency, and streamline operational processes. These advantages allow forest operators to increase their timber output and conduct more systematic and intensive management activities, thereby improving the overall capacity and quality of forest management. Numerous studies have examined scale management through the lens of agricultural land leasing. Empirical evidence suggests that the explosive growth of non-agricultural labor markets acts as a primary catalyst for increased land leasing activities [

6], while demographic aging facilitates land transfer from elderly to younger households, thereby fostering land lease market development [

7]. A Vietnam-based study demonstrated that secure land rights significantly expand the land supply in lease markets [

8]. Research on Chinese agriculture revealed that households renting additional land exhibit higher productivity, with developed land leasing markets substantially boosting rice yields in Southeastern China [

9]. These findings underscore the indispensability of land lease markets, which may substitute administrative land redistribution to optimize land allocation [

10], mitigate the adverse effects of land fragmentation [

11], and transfer land to more capable producers, thereby enhancing agricultural productivity [

12]. Furthermore, such markets help to prevent widening income disparities between households engaged in agricultural production and those transitioning to non-agricultural sectors [

13].

However, the consolidation of land from smallholders to large-scale operators signifies the gradual displacement of family-based management entities, potentially undermining the stability of rural fundamental management systems [

14]. In addition, households face a dual set of challenges associated with land leasing. On the one hand, the absence of robust land protection regulations increases the likelihood of disputes arising from land leasing [

15], potentially resulting in the involuntary loss of land rights. On the other hand, after leasing their land, many farmers struggle to integrate into the urban labor market, often experiencing income instability and a lack of adequate social security. These issues may lead to political risks that should not be overlooked. Moreover, forestry production inherently differs from agricultural practices. The protracted growth cycles of timber, the spatial dispersion of forestland, and concentrated investment requirements render households more circumspect in regard to forestland leasing compared to agricultural land transactions, posing substantial challenges in achieving operational scale economies in practice. These constraints indicate that, while land transfer facilitates scale effect formation, the realization of forestry scale operations through this mechanism in China remains hindered by systemic barriers under the current conditions.

In the past, agricultural scale operations in China were primarily achieved through land consolidation via farmland leasing. However, a growing trend toward service-based scale operations has emerged, where individual farmers retain land ownership but specialized service providers achieve economies of scale by serving a large number of clients. Some research suggests that transitioning from land-scale to service-scale operations constitutes a critical pathway aligning with China’s agricultural transformation [

16]. Production segment outsourcing enables scale economies to a greater extent than via land transfers [

17]. Achieving optimal agricultural scale operations necessitates enhanced socialized service systems, rather than relying solely on land transfers. High-quality service outsourcing markets effectively catalyze land transfer [

18], with the organic integration of agricultural services and moderate land-scale operations expanding the agricultural scale economy dimensions [

19]. Without corresponding socialized services, the scale effects from land transfers remain suboptimal [

20]. The co-evolution of land transfer and machinery services fosters large-scale operators [

21], where land-scale and service-scale operations exhibit mutual reinforcement [

22]. Service outsourcing opens up a new path for agricultural modernization through service-oriented scale operations, distinct from traditional land consolidation methods [

23].

In addition to achieving economies of scale through large-scale production, the accumulation of experience by repeatedly performing the same production tasks can improve efficiency and reduce costs, thus achieving economies of scale. Moreover, the development of markets for forestry inputs such as labor, capital, and land can, to varying degrees, incentivize households to increase their input levels in forestry management, thereby enhancing their enthusiasm for engaging in forestry production [

24]. It can thus be seen that specialized service providers not only help households to improve their production efficiency through professional service standards but also create positive externalities via technological spillovers, thereby enhancing the overall forestry development level of the region. This provides new perspectives for the achievement of large-scale forestry operations, enhancing forestry management and promoting sustainable forestry development. This implies that, as specialized production advances, once the production service market in a region reaches a certain level of development, households may voluntarily choose to purchase production services [

25]. Local producers will no longer need to rely solely on land transfers to improve their production efficiency, but instead can enhance their efficiency by opting to purchase services. Furthermore, as service providers continually improve their expertise during service provision, households’ willingness to purchase these services increases correspondingly, leading them to retain their forestland management rights.

This study consequently addresses three pivotal questions: (1) How do regional forestry service provider characteristics influence household forestland rights retention decisions? (2) How do terrain heterogeneity and production difficulties modulate these choices? (3) How do the opportunity costs of non-agricultural employment affect decision-making? The current research predominantly overlooks forestry service organizations and their market impacts on household behavior. Our findings will provide theoretical and practical insights for forestry development strategies and innovative management, contributing novel perspectives to academic and policymaking circles.

2. Theoretical Analysis

In the 1980s, agricultural and forestry production were the primary sources of income for rural Chinese households. However, with the rapid expansion of China’s non-agricultural employment market, income growth from agriculture and forestry significantly lagged behind that of other sectors. As a result, farming or forestry alone could no longer cover basic household expenses, prompting some rural households to leave their hometowns in search of job opportunities in cities. Consequently, many households migrated to urban areas, seeking employment opportunities. As a result, much of the labor force capable of engaging in forestry activities, such as planting, logging, and tending, was also forced to withdraw from forestry production. The outflow of rural labor to cities reduced the overall supply of labor in rural areas and led to an increase in the cost of hired labor [

26]. As a consequence, some households have gradually reduced their engagement in forestry production. Against the backdrop of shifting factor endowments driven by rising labor costs, capital emerged as a substitute for labor [

27]. In response, some producers adopted machinery to mitigate escalating labor expenses.

With the increase in household machinery ownership, some households accumulate asset specificity in their machinery, begin to specialize in agricultural production, and attempt to lease land from other households or become machinery service providers. In the outsourcing agricultural machinery service market, the labor substitution effect of outsourcing influences land leasing; the more machinery services that households purchase, the more inclined they are to lease land in and the less likely they are to lease land out [

28]. A household survey in rural Indonesia demonstrated that, as real wages in both the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors generally increased, households expanded the scale of their operational land through leasing and hired more machinery services, achieving the substitution of machines for labor [

29]. This phenomenon elucidates why small farms exhibit a higher labor intensity per unit area, whereas large farms prioritize proprietary mechanization investments [

30]. In forestry production, this phenomenon is even more pronounced. Activities such as afforestation, tending, and harvesting are labor-intensive, and the use of machinery significantly enhances the production efficiency. During the tree planting stage, specialized pit-digging equipment enables the precise and efficient excavation of planting holes. In the tending phase, brush cutters effectively clear understory vegetation, significantly reducing the labor intensity of manual weeding. In the harvesting stage, professional logging equipment not only enhances the production efficiency but also ensures operational safety. However, considering the forestry production cycle, high-frequency forestry activities mainly occur during the first three years of afforestation, while the rest of the period requires much lower labor and machinery inputs. This means that the vast majority of households do not necessarily need to purchase machinery, especially considering the high costs associated with owning and maintaining such equipment. If the market offers suitable service outsourcing organizations, they can seek external assistance by purchasing production services.

The proliferation of labor-substituting outsourcing services enables households with non-agricultural employment capabilities to disengage from forestry production, reallocating labor to more remunerative sectors. Non-agricultural employment reduces the small machinery ownership likelihood due to service market substitution effects [

31]. From a division-of-labor perspective, outsourcing enhances productivity [

32], explaining the sustained agricultural growth in China’s fragmented, labor-costly landscapes through specialized mechanized service providers. These providers support smallholders in labor-intensive, machinery-dependent production phases, sustaining smallholder viability through task outsourcing [

33].

Practice has shown that various socialized services help producers to master technology, thereby improving the agricultural production efficiency [

34]. In order to reduce the production costs, households substitute labor with machinery [

35], and machinery services significantly influence the adoption of no-tillage and organic fertilizer application techniques [

36]. The scale and development level of agriculture in a county are positively correlated with local non-agricultural employment and agricultural mechanization [

37], and production outsourcing is regarded as key to boosting grain yields [

38], while simultaneously increasing household incomes and improving labor convenience to enhance the welfare of small households [

39]. Furthermore, the development of the outsourcing services market can significantly reduce the rate of land abandonment caused by land fragmentation [

40]. Agricultural extension services can even be utilized to improve households’ ability to cope with climate variability [

41].

Thus, outsourcing services introduce modern production factors, entrepreneurial capabilities, and organizational methods, which help smallholder households to realize the economic benefits of the division of labor. Service organizations and outsourcing providers will eventually replace smallholder households as the main drivers of agricultural investment, technological advancement, and improved management practices [

42]. Post-collective forest tenure reform, households with limited land resources and production capacities increasingly outsource forestry tasks to professional service organizations. This strategy minimizes land transfer risks while improving productivity, incentivizing households to retain their forestland management rights for sustainable income generation.

However, geographical dispersion among smallholders escalates the service supervision costs [

43], particularly in remote forested areas, where service accessibility and monitoring complexities inflate transaction expenses. Concurrently, outsourcing service prices rise with non-agricultural market development. Research on outsourcing in Chinese agriculture has found that the mechanized services market is often unfavorable for the survival of small households. The pricing of agricultural mechanized services tends to weed out less productive households and foster the emergence of new agricultural operators [

44].

In conclusion, as the division of labor deepens, some households, after long-term accumulation, begin to engage in specialized forestry production activities and provide outsourcing services to other households, leading to the gradual development of a forestry production service market. When households opt for non-agricultural employment, they can still carry out forestry production by purchasing outsourcing services. This approach allows them to avoid the high costs of purchasing expensive equipment while also benefiting from the ability of professional service organizations to mobilize experienced forestry labor. As a result, the forestry production efficiency can be enhanced through specialized service provision. At the same time, they can avoid potential risks and disputes related to leasing their land, retaining their forestland management rights. Consequently, the path to achieving large-scale forestry production shifts from the traditional model of production-scale operations to a service-oriented scale operations model. This transition further enhances the sustainability of forestry management and lays a solid foundation for the long-term and stable development of the forestry industry.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 1: The development of forestry service outsourcing organizations reduces the likelihood of forestry households leasing out their forestland.

Hypothesis 2: The development of forestry service outsourcing organizations reduces the area of forestland leased out by forestry households.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

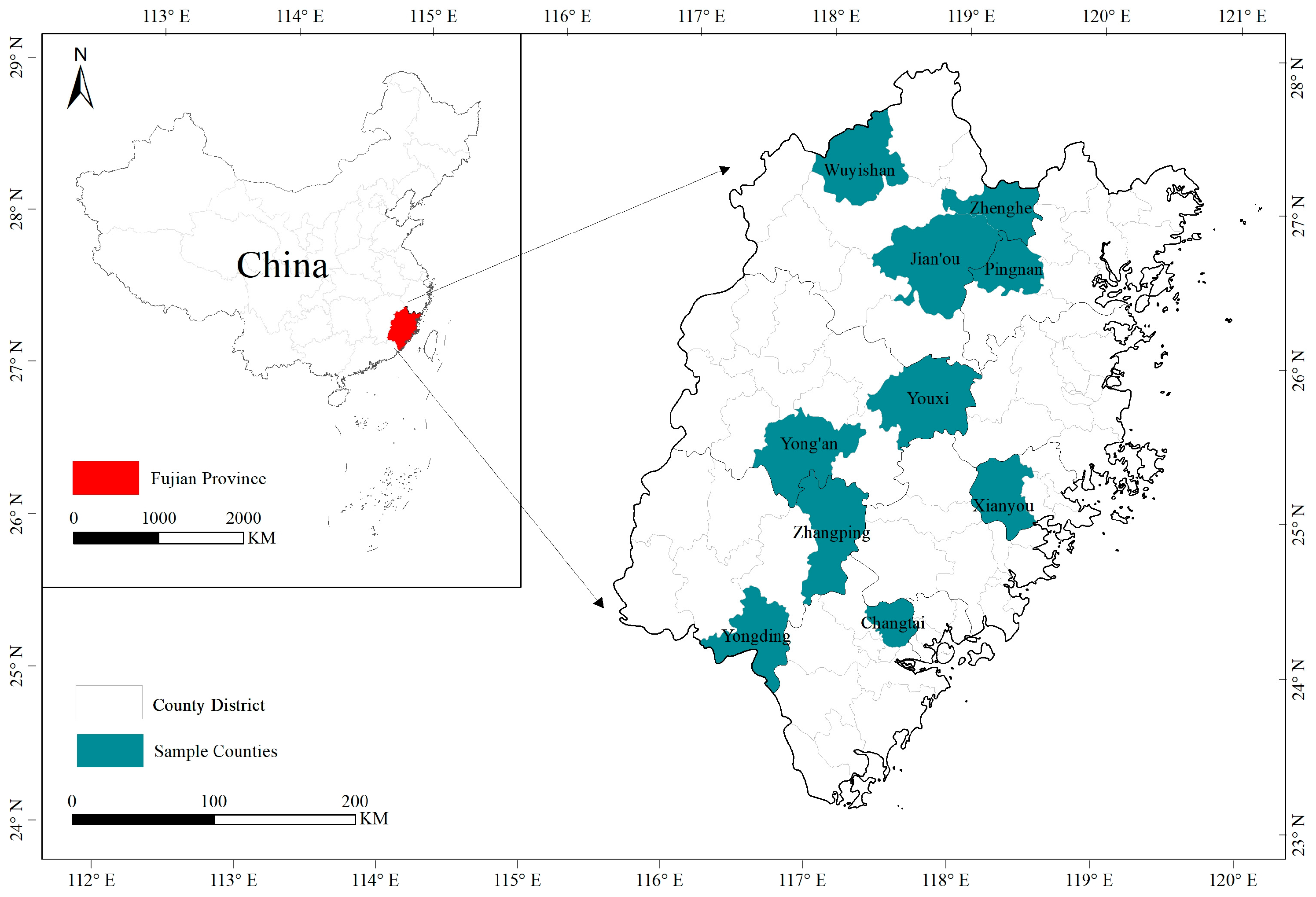

Fujian Province, located in Southeastern China, is a key collective forest region and a crucial ecological barrier along the coast. Fujian leads the nation, with a forest coverage rate of 65.12%. Fujian was the first province to implement collective forest tenure reform, offering valuable experience and policy models nationwide. The province also boasts a diverse ecological system. Its forestry industry is highly developed, with a total output value of CNY 812.1 billion in 2024, placing it among the top in the country for the production of wood, bamboo, flowers, activated carbon, and wooden furniture.

The data used in this study are primarily derived from the “Monitoring of Collective Forest Tenure Reform” project, a major research initiative organized by the National Forestry and Grassland Administration of China. This government-led investigation focuses on tracking the progress of collective forest tenure reform across several provinces, including Fujian and Jiangxi. Some existing studies have utilized data collected from other regions within this monitoring program [

45]. Fujian was one of the earliest regions in China to explore reforms of the collective forest tenure system and is also the province with the highest forest coverage in the country, making forestry households in Fujian a representative sample. Using a typical sampling method, our research team identified 10 forest resource-rich counties with forestry reform monitoring in Fujian—namely Wuyishan, Jian’ou, Pingnan, Xianyou, Yong’an, Yongding, Youxi, Zhangping, Changtai, and Zhenghe. From each county, 50 forestry households were randomly selected as fixed samples, resulting in a total of 500 households, which were then tracked annually over a six-year period from 2013 to 2018. The survey region is shown in

Figure 1. However, due to issues such as the unavailability of sample households during field visits, the research team adjusted the sample size. The six-year survey ultimately produced an unbalanced panel dataset involving 1174 different forestry households, of which 58% participated in at least two survey rounds. A total of 2780 valid questionnaires were collected, all through face-to-face interviews conducted by students from Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University.

3.2. Research Design

This study aims to estimate the impact of regional forestry service outsourcing organizations on households’ forestland leasing behavior from two dimensions: the decision to lease out and the scale of leased forestland. Accordingly, two dependent variables are defined. The first is a binary variable indicating whether the household leased out forestland (1 = yes, 0 = no); the second is a non-negative continuous variable, measured as the logarithm of the leased forestland area. The key explanatory variables are “years since the establishment of county-level project teams” and “years since the establishment of county-level forestry companies”, used to measure the development of forestry service outsourcing organizations at the county level. To effectively identify the impact of forestry service outsourcing organizations on forestry households’ leasing behavior, this study constructs panel data models based on the characteristics of the data.

First, in the model examining forestry households’ participation in leasing out their forestland, the dependent variable “whether forestland is leased” is a binary variable, so a panel binary choice model is specified. The panel binary model can be estimated using various methods, including pooled regression, random effects, and fixed effects models. Since the panel Probit model does not accommodate fixed effects, a panel Logit model is used. Based on our dataset, the panel Logit random effects model is selected for estimation (see Equations (1)–(4)).

characterizes the forestland leasing characteristics of households

in the period

.

is represented as a discrete random variable taking values of 0 and 1, defined as follows:

The relationship between

and

is defined as follows:

Assuming that

follows a logistic distribution, the panel Logit model is specified as:

Secondly, a model for the scale of forestland leasing by forestry households is established. Based on the characteristics of the dataset, we consider the choice between a panel Tobit pooled regression model and a panel Tobit random effects model. By examining individual heterogeneity, the LR test yields a value of 0, indicating the presence of individual effects; thus, the panel Tobit random effects model is selected (see Equations (5) and (6)).

In Equations (1) and (2), the dependent variable is a binary choice variable indicating whether forestry households have leased out their forestland in year (1 if leased out, 0 if not). In Equations (3) and (4), the dependent variable represents the scale of forestland leasing by forestry household in year , measured as the logarithm of the leased area; for all samples, 1 is added to the forestland leasing area to resolve the issue of taking logarithms when the area is zero.

In practice, county-level forestry project teams and forestry companies are the two main forms through which households access outsourced production services. Therefore, when discussing forestry service outsourcing organizations in this study, the primary focus is on project teams and forestry companies. For each, the earliest establishment year of the relevant organization in the county where the forestry household is located, as of the cutoff year , is used to measure the development of forestry service outsourcing organizations, corresponding to the key explanatory variables and in Equations (1)–(4).

denotes a series of control variables affecting forestland leasing behavior in Equations (1)–(4), including the characteristics of the household head, household characteristics, forestland characteristics, and village characteristics. and represent the unobserved individual effects, and represent the unobserved time effects, and are the idiosyncratic error terms, and are parameters to be estimated.

3.3. Variable Description

This study focuses on two primary types of forestry production service organizations: county-level project teams and county-level forestry companies.

Table 1 presents the systematic differences between the two in terms of the scope of operation, business activity, service target, registration location, staff composition, and operating cost. In comparison, forestry companies demonstrate a higher degree of formalization, primarily serve large-scale operators, and maintain a more complete staffing structure, whereas project teams are more flexible, rely more on township-level resources, and have a leaner personnel composition.

Table 2 further illustrates the development of forestry service organizations. It can be observed that the average establishment duration of county-level forest project teams increased from 9.09 years in 2013 to 14.27 years in 2018, showing a linear growth trend, which reflects the continued operation of mostly the same set of organizations. The standard deviation remains stable at around 4, suggesting a certain degree of dispersion in the development of project teams across counties. In contrast, county-level forestry companies have been established for a longer period, with an average of nearly 24 years. The increase over time is also linear, indicating that the sample largely consists of long-standing companies in continuous operation. The standard deviation of forestry companies’ establishment duration is approximately 5, higher than that of project teams, suggesting a wider distribution of founding years.

Table 2 also presents the forestland leasing behavior of the sample households and its changing trend. It can be seen that the incidence of forestland leasing is very low, with an overall average of only 2.48%. Although there are slight fluctuations across the years, the overall variation is limited, remaining between 1.94% and 3.17%. The standard deviation of whether leasing occurred is 0.1352–0.1754, indicating a high degree of concentration in the data. In terms of the leasing scale, the overall average is 0.1038, indicating that the actual area leased is very limited. However, the standard deviation consistently exceeds the mean, suggesting that most households leased out only a small amount of forestland, while a small number of households leased relatively large areas.

In addition, this study includes a range of control variables to account for potential confounding factors affecting farmers’ forestland leasing behavior. These include household head characteristics such as gender, age, years of education, part-time status, cadre experience, and training experience; household characteristics such as income and the proportion of forestry labor; forestland characteristics such as the area and tenure certification status; and village-level characteristics such as the terrain and distance to county and township centers. It should be specifically noted that cadre experience in this study refers to whether the household head has ever served as a village cadre. In villages in China, compared to ordinary farmers, village cadres are representatives of the government [

46], and they possess advantages in terms of social capital and access to information resources, potentially making them more inclined to participate in land market activities. Descriptive statistics for the above variables are shown in

Table 3.

4. Analysis of Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

Table 4 reports the estimation results regarding the impact of forestry service outsourcing organizations on forestland leasing behavior. Columns (1) through (6) are based on 2780 observations from 1174 forestry households. Specifically, Columns (1) to (3) focus on the dependent variable “whether forestland was leased out” and are estimated using a panel Logit model. Given that the coefficients from the Logit model are not easily interpretable in economic terms, the results are reported in terms of odds ratios to provide more meaningful economic interpretations. Columns (4) to (6) focus on the dependent variable “scale of forestland leasing” and are estimated using a panel Tobit model, with coefficients reported. The results show that, whether for “whether forestland was leased out” or for the “scale of forestland leasing”, the establishment durations of both county-level forest project teams and county-level forestry companies exhibit a negative relationship, with odds ratios of less than 1 or negative coefficient signs, and they are all significant at the 1% level. This indicates that the development of forestry production service organizations has a significant suppressive effect on households’ decisions to lease out forestland and on the scale of leasing. This result remains robust after the inclusion of control variables. Specifically, holding other conditions constant, each additional year of existence for county-level forest project teams and forestry companies reduces the relative probability of leasing out forestland by 35% (1 − 0.6489) and 26% (1 − 0.7412), respectively. This finding is intuitive: from the supply side, the longer that a county-level forestry service organization has been established, the more standardized its operations become, thereby enhancing its service capabilities and social credibility. For the demand side—that is, forestry households—given the division of labor theory and the large-scale, professional nature of forestry outsourcing services, more standardized and stable services reduce the difficulty and cost of hiring professional production services, while increasing the benefits. Consequently, the relative opportunity cost of leasing out forestland rises, strengthening the households’ preference for purchasing production services and retaining their management rights.

4.2. Robustness Checks

To ensure the robustness of the above regression results, we first re-test by replacing the key explanatory variables. Specifically, we substitute the key variables “county-level project teams’ establishment duration” and “county-level forestry companies’ establishment duration” with the “township project teams’ establishment duration”. Prior to this, we examine whether a township has a forestry project team. This approach has two practical implications. First, townships in China are smaller administrative units than counties and are the closest administrative division to forestry households. As long as a township has a well-managed forestry project team, households are highly unlikely to seek assistance from other townships. Therefore, examining township-level forestry project teams can more precisely and directly demonstrate the impact of forestry service outsourcing organizations on households’ forestland leasing behavior. Second, there is significant variation in the establishment status of project teams at the township level. Among the 1174 forestry households surveyed, only 588 are located in townships with a forestry project team. Reflecting on the overall dataset—where some households participated in multiple survey rounds—only 1206 out of 2780 observations come from townships with a forestry project team, which better represents the real constraints faced by households.

Table 5 presents the estimation results regarding the effect of township project teams’ establishment duration on forestland leasing behavior. Columns (1) and (3) examine the impact of the presence of forest project teams at the township level on households’ decisions to lease out forestland and the scale of leasing out. Both are significant at the 1% level, with odds ratios of less than 1 or negative coefficients. Columns (2) and (4) examine the effect of the number of years since the establishment of the township forest project teams on the leasing out of forestland by foresters and the scale of leasing, both of which are significant at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively, with either odds ratios < 1 or negative coefficients. These results indicate that the existence of a forestry project team at the township level significantly suppresses both the likelihood and the scale of forestland leasing by households; those in townships with a forestry project team are less likely to lease out their forestland compared to those in townships without one, and, among households in townships with a forestry project team, the longer that the team has been established, the lower the likelihood of forestland leasing. Specifically, holding other conditions constant, compared with townships without forest project teams, the relative probability of farmers leasing out forestland in townships with such teams decreases by approximately 91.88% (1 − 0.0812). For each additional year of existence of a township-level forest project team, the relative probability of forestland leasing decreases by approximately 44.97% (1 − 0.5503). These regression results are consistent with the baseline regressions.

Secondly, this study applies two-sided winsorization at the 1st and 99th percentiles for all continuous variables to further examine the robustness of the results. The results are presented in

Table 6. With the same structure as

Table 2, Columns (1) to (3) and Columns (4) to (6), respectively, examine the impact of the duration of establishment of county-level forestry project teams and forestry companies on whether forestland is leased out and on the scale of forestland leasing. These results are essentially consistent with the baseline regressions, further confirming the robustness of our findings.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

This study attempts to examine the impact of forestry service outsourcing organizations on forestland leasing from two perspectives—the forestland topography and households’ engagement in non-forestry activities—in order to uncover additional information that may be concealed in the baseline regression results.

Topographic features are a key factor affecting the difficulty of forestry production. They not only influence the growing conditions of the crops themselves but also lead to differences in households’ use of machinery. Due to the long cycle of forestry operations and the general lack of production experience among most households, those who only cultivate their own forestland tend to have relatively lower levels of forestry management. Consequently, the production difficulties imposed by the topography are bound to affect households’ production behavior choices. To further examine this key factor, this study categorizes the sample forestland into two groups—plain and hilly regions and mountainous regions—and investigates whether the impact of forestry service outsourcing organizations on forestland leasing by households varies with topographic heterogeneity. There are 1670 observations (involving 699 sample households) in the plain and hilly region group and 1110 observations (involving 478 sample households) in the mountainous group; the regression results are presented in

Table 7.

The results are essentially consistent with the baseline regressions. Specifically, holding other conditions constant, in the plain and hilly sample, each additional year of existence of a county-level forest project team reduces the relative probability of forestland leasing by approximately 48.85% (1 − 0.5115), while county-level forestry companies exhibit a stronger suppressive effect, reducing the relative probability by nearly 50.05% (1 − 0.4995). In contrast, in mountainous areas, each additional year of existence of county-level project teams and forestry companies reduces the relative probability of forestland leasing by only 26.84% (1 − 0.7316) and 10.09% (1 − 0.8991), respectively. This indicates that, in regions with flatter terrain, the development of forestry service organizations plays a more significant role in influencing households’ decisions regarding forestland leasing. It is noteworthy that the duration of establishment of forestry companies does not have a significant effect on the scale of forestland leasing in the mountainous group. One possible explanation is that, compared with forestry project teams, forestry companies tend to rely more on the use of forestry machinery to substitute labor, and the advantages of machinery are more pronounced in larger-scale forestland. However, the efficient and normal use of machinery is constrained by the topographic conditions. In mountainous areas, the labor substitution effect of machinery is diminished; therefore, the duration of establishment of forestry companies cannot significantly affect the scale of forestland leasing by households.

Table 8 examines the part-time status of households. There are 1199 observations from part-time households, involving 652 households, and 1581 observations from full-time households, involving 803 households. Part-time farming refers to situations where forestry households engage in other occupations outside of forestry production, which require significant time investments and generate a substantial portion of their income. The results indicate that, for part-time households, the duration of establishment of forestry service outsourcing organizations significantly reduces both their forestland leasing behavior and the scale of leasing. Each additional year of existence of county-level forest project teams and forestry companies reduces the relative probability of forestland leasing by 30.09% (1 − 0.6991) and 29.96% (1 − 0.7004), respectively. For full-time households, forestry production service organizations significantly suppress the leasing out of forestland, with each additional year of existence of county-level forest project teams and forestry companies reducing the relative probability by 40.13% (1 − 0.5987) and 22.54% (1 − 0.7746), respectively. However, the effect of the establishment duration of county-level forestry companies on the scale of forestland leasing among full-time households is not statistically significant. For full-time households, these organizations significantly suppress forestland leasing, but the effect on the leasing scale is not significant. Field visits suggest that full-time households, who primarily rely on forestry for their livelihood, have sufficient awareness of forestry production’s difficulties, costs, and returns. Some full-time households have long been engaged in forestry production in forest areas and have gradually improved their level of specialization. In this context, two trends can be observed: one is that households with a certain level of economic foundation may evolve into specialized production organizations dedicated to forestry operations, which may lead them to lease in additional forestland to expand their scale of production. Alternatively, they may both manage their own production and provide services to other households; on the other hand, relatively impoverished households who rely primarily on family-based production maintain only weak links with county-level forestry companies, so the development of the production service market is not closely related to them. Consequently, the development of forestry companies does not significantly affect the leasing scale among full-time households.

5. Discussion

This study investigates the relationship between the development of forestry project teams and forestry companies and the leasing behavior of forestland by households, and it finds that the advancement of forestry service outsourcing organizations in the regions where households are located reduces their willingness to lease out land. This suggests that, when specialized service outsourcing organizations emerge in the market, households are less likely to lease out their forestland, making service-oriented scale operations a viable approach to promoting large-scale forestry operations.

For decades, scale management has been recognized as a critical strategy to enhance land use efficiency [

47]. Small farm sizes and fragmented landholdings prevent households from achieving economies of scale, leading to technical inefficiencies [

48]. Following China’s collective forest tenure reform, forestland management rights were allocated to households, resulting in a “small and fragmented” landholding pattern. Addressing this issue remains a pressing challenge. However, most scholarly attention has focused on agricultural sectors, with limited exploration of forestry specialization or the role of forestry service outsourcing organizations in sustainable forestry development—a gap that this study aims to fill.

Our analysis demonstrates that the longer that forestry service outsourcing organizations have operated in a county, the less inclined households are to lease out forestland, with significantly reduced leased areas. Similar conclusions exist in agricultural research: the development of the agricultural outsourcing service market alters households’ farmland transfer behavior, leading to decreases in both the probability and the area of leased land [

49]. We cannot deny that the emergence of service outsourcing organizations provides opportunities for those who wish to specialize in agricultural operations, which also explains why some agricultural studies have observed an expansion in the scale of operators. Research in agriculture has found that production services exert a positive influence on households’ decisions to acquire farmland [

50], encouraging large-scale operators to increase farmland leasing [

51] and promoting large-scale farmland operations [

52]. Studies on American agriculture have also shown that households expand their land management areas as a result of using agricultural machinery [

53]. However, further research has found that improvements in the level of outsourcing services promote increased land leasing among large-scale operators, while the impact on small households is relatively weak [

54]. The growth of production service markets provides opportunities for investors seeking to specialize in agricultural operations, enabling them to expand the production scale through capital-for-labor substitution and transitions from producers to investors. However, such a phenomenon is unlikely to materialize in China’s forest regions in the near term.

China’s forested areas are predominantly located in mountainous regions, which overlap significantly with poverty-stricken zones. For many households, forest resources serve as critical productive assets. Their primary concern is leveraging these assets to meet basic subsistence needs, rather than pursuing profit maximization through expanded production. In China, it is said that “those who live by the mountains live off the mountains; those by the sea live off the sea.” For households in forested areas, arable land is very limited. While they may occasionally spend time growing simple vegetables, forestry remains their main source of income, and they devote most of their working time to forestry operations. Additionally, the lengthy cycles of forestry operations exacerbate households’ anxieties: once forestland is leased out, households risk losing their income sources for extended periods. Consequently, households exhibit strong reluctance to transfer forestland and retain their management rights with exceptional tenacity. This reluctance hinders the realization of economies of scale in forestry. Furthermore, the inherent characteristics of forestry production—particularly its long cycles, with critical forest management activities concentrated in the first three years of afforestation—impact this. Households who lack engagement with forestry production services and focus solely on managing their own plots face high costs in acquiring scientific afforestation and silvicultural techniques from scratch. This impedes the accumulation of forestry expertise. Individual households rarely invest in specialized forestry machinery, perpetuating low production efficiency. These dual factors—strong land retention incentives and limited technical capacity—explain why forestry productivity improvements lag behind agriculture and exhibit slower growth rates compared to other industries.

The paramount value of this study lies in its exploration of household behavior through the lens of forestry production services. We demonstrate that the development of service outsourcing organizations incentivizes households to retain their forestland management rights—a finding that offers novel insights toward advancing forestry scale operations, improving its efficiency, and fostering sustainable forestry development. Specifically, when households tend to retain their management rights but have relatively low production capabilities, the development of service outsourcing organizations can assist them in carrying out production tasks, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of forestry management. In this process, service outsourcing organizations provide households with efficient production services through the accumulation of experience and the utilization of machinery. As these service organizations gradually mature and eventually achieve service-oriented scale operations within the region, the cost for households to purchase outsourced services decreases, the transaction frequency increases, and the development of these organizations is further promoted. Consequently, the overall efficiency of forestry management in the region is enhanced.

This study further reveals that the inhibitory effect of forestry service outsourcing organizations on forestland leasing is particularly pronounced among households in plain and hilly regions and those engaged in part-time forestry production. For households in plain and hilly regions, beyond the mechanization advantages discussed earlier, the relatively flat terrain reduces the service procurement costs (e.g., easier machinery deployment) and enhances interpersonal communication, thereby lowering the transaction expenses. Additionally, forestland in these regions often yields higher economic returns. Consequently, as service outsourcing organizations develop, households here have stronger incentives to retain their management rights to maximize the returns on their investments. The outsourcing service market is not static but evolves through phases of development, stabilization, and decline [

55]. This dynamic compels forestry operators to balance household-specific endowments with the broader market conditions when making decisions. As information transparency and dissemination accelerate in service markets, households increasingly adapt to the evolving conditions, opting to participate in specialized economies based on cost–benefit calculations. This reshapes the transaction density and spatial reach within production service markets [

56], ultimately influencing the developmental trajectory of service organizations in a region. Our study further reveals that the longer the establishment history of township forestry project teams, the more inclined households are to retain their family forestland management rights. In fact, township forestry project teams typically operate within a specific township, and the vast majority of their clients are introduced through personal connections—often involving relatives or friends—making it easier to establish mutual trust with households. When the level of trust in a region increases, it may lower the transaction costs associated with collective action among households [

57].

As trust solidifies, more households feel assured when purchasing production services. Forestry service outsourcing organizations, in turn, accumulate technical expertise and mechanized capabilities through repeated engagements, improving the service quality. Over time, households gain access to superior services at comparable or reduced costs, reinforcing their willingness to retain their management rights. Within this evolving regional ecosystem, the forestry operational efficiency improves markedly. By harnessing economies of scale in forestry services, sustainable development becomes achievable, driving systemic advancements in the sector.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Conclusions of the Research

Since 2003, when China initiated the collective forest tenure reform, rapid growth in forestry resources has synergized rural income growth and environmental conservation—a consensus that is widely acknowledged. However, an undeniable reality persists: some households, reluctant to transfer their forestland management rights and increasingly engaged in non-agricultural employment, have neglected forestland management, resulting in slower productivity improvements compared to other sectors. This study identifies forestry service outsourcing organizations as pivotal agents in transforming this status quo. These organizations enable smallholders to retain their management rights while accessing professional production services and gradually achieve service-oriented scale operations through expanded service coverage. Such mechanisms hold critical implications for the design of future forestry policies to support smallholder development.

Using data from Fujian Province, the birthplace of China’s collective forest tenure reform, this study explores the relationship between the development of forestry service outsourcing organizations and households’ operational choices. The results demonstrate that the duration of establishment of both county-level forestry project teams and forestry companies suppresses households’ tendency to lease out their forestland, particularly for those in plain and hilly regions and part-time forestry producers. At the same time, we find that the longer that the township forestry project teams have been established, the more likely households are to retain their family forestland management rights. Based on these findings, it can be inferred that the development of forestry service outsourcing organizations helps households to retain their forestland management rights. In an environment where the non-agricultural employment market is rapidly expanding, forestry service outsourcing organizations facilitate households’ retention of their management rights, enhance the forestry production efficiency, mitigate the risk of land loss, and reduce the abandonment of forestland. As forestry service outsourcing organizations continue to grow and mature, forestry production is gradually transitioning toward a new stage of service-oriented scale operations. This trend indicates that placing a strong emphasis on the development of forestry service outsourcing organizations has become a key focus in promoting the sustained progress of the forestry industry.

Building upon the existing literature on scale operations in forestry and agriculture, this study expands the current research paradigm that primarily centers on land transfer. Unlike previous studies that emphasize land leasing and household exit mechanisms, this paper systematically examines how the development of forestry service outsourcing organizations influences households’ decisions to retain their forestland management rights—an approach grounded in the unique characteristics of forestry, such as long production cycles, complex terrain, and high technical thresholds. It proposes a novel explanatory framework whereby households become less likely to exit forest production by purchasing specialized services, thereby strengthening their willingness to retain their land management rights. This provides a fresh perspective in understanding how household-based operations can achieve scale and specialization without relinquishing land use rights. In addition, by incorporating terrain heterogeneity and labor opportunity costs, this study uncovers differentiated mechanisms through which service organizations affect household decisions regarding forestland. It enriches the understanding of how labor migration and specialized services jointly shape forestland allocation behavior. These insights offer a transferable theoretical framework and empirical reference for future research exploring pathways to scaled operations in forestry.

This study reveals the significant inhibitory effect of forestry service outsourcing organizations on forestland leasing behavior and proposes a pathway to achieving scale operations in forestry by expanding service provision rather than relying on land transfer. This mechanism is particularly relevant in developing regions, where forestland ownership is fragmented, part-time farming is prevalent, and the cost of traditional land consolidation remains high. In many areas facing challenges such as fragmented forest plots, low production efficiency, and increasing rural-to-urban labor migration, the difficulty in promoting land transfer is often accompanied by rising risks of forestland abandonment. These conditions closely resemble the practical context observed in Fujian, China. Under such circumstances, scaling forestry operations through the development of service markets presents an effective approach to enabling smallholders to retain their forestland management rights and improve their production capacity. It also provides practical guidance for the design of forest governance models that balance ecological conservation with rural household income generation, making this study’s insights broadly applicable across regions with similar structural characteristics.

6.2. Policy Recommendations Based on Research Findings

First, it is necessary to establish a multi-stakeholder resource integration mechanism. Forestry service outsourcing organizations ought to focus on the core task of resource integration, comprehensively bringing together various elements, such as capital, technology, and management experience. Government departments should take proactive measures to build regional or county-level comprehensive service platforms, efficiently consolidating the resources of dispersed households and enhancing the precision and efficiency of resource allocation. At the same time, the government should fully exercise its guiding role by encouraging extensive cooperation among service organizations, as well as between these organizations, local governments, and households. Through complementary advantages and coordinated efforts, the intensification and professionalization of forestland management can be significantly improved, ultimately achieving optimal resource allocation and efficient utilization.

Second, it is necessary to advance intelligent forestry management systems. Forestry service outsourcing organizations should actively embrace technological innovations and vigorously adopt advanced techniques such as drone monitoring and IoT sensor technology to comprehensively optimize and upgrade forestland management and monitoring. By leveraging precise data collection and in-depth analysis, production inputs can be allocated scientifically to minimize resource waste, achieving refined management and efficient operations in forestry production. Additionally, government departments should regularly organize technical training activities for forestry service outsourcing organizations, widely promote new production skills and advanced management concepts, and continuously enhance the technological content of forestry production, thereby injecting a steady stream of momentum for the sustainable development of forestry production services.

Third, it is necessary to innovate value-added services across the forestry industry chain. Forestry service outsourcing organizations should explore diversified business models to expand the forestry industrial chain. In addition to traditional practices such as tree cultivation and tending, there should be an increased focus on developing ecological products—such as forest tourism, wood deep processing, and derivative products—to enhance the added value of forestry products. Government departments must strengthen the market orientation and innovation capacity of service organizations, guiding them to accelerate their transition toward diversified operations and establishing a comprehensive, multi-tiered service system that provides robust support for the sustained and healthy development of forestry production. This, in turn, will promote steady progress in the forestry industry along a diversified development path. Through these measures, forestry service outsourcing organizations can better help households to retain their management rights, improve the efficiency of forestry production and operations, and steadily drive forestry production toward greater specialization and scale, thereby laying a solid foundation for the sustainable development of forestry.

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

First, one limitation of this study lies in the use of data from several years ago, which may appear somewhat outdated. However, the data were collected during a critical period, when the effects of China’s forest tenure reform were emerging and forestry service outsourcing organizations were undergoing rapid development. Given that the overall trajectory of forestry development has remained consistent, the data still retain a certain degree of representativeness. Future research should revisit this relationship using more recent data to capture potential changes in household production behavior and the evolution of service outsourcing organizations.

Second, a limitation of this study lies in its variable selection. We use the periods since the establishment of county-level project teams and companies as proxies to measure the development levels of these organizations. At present, these are the most appropriate variables available. However, as the public understanding of various types of forestry service organizations deepens, identifying more refined indicators to capture the development of forestry service outsourcing organizations remains a valuable direction for future research. In addition, we included several control variables. In practice, when we conducted field interviews with forestry households, their forestland management decisions had already been made, which may have led to some temporal and spatial mismatches between the control variables and the decision to lease out forestland. This mismatch could potentially introduce bias. Fortunately, variables such as individual endowments and the household composition exhibit a high degree of temporal stability. Moreover, our results show that these control variables did not significantly affect the dependent variable, which enhances the credibility of our findings. In future studies, we aim to improve the dynamic monitoring of the observed subjects to better understand households’ operational behaviors.

Third, although the Introduction of this study referred to issues of ecological protection and household income, the analysis did not directly examine how these outcomes were affected. Instead, the research focused on farmers’ operational decisions from the perspective of forestry service outsourcing organizations. Future studies should incorporate relevant variables to further investigate the potential influences of these organizations on regional ecological sustainability and rural household income improvement.