Benefits Beyond the Physical: How Urban Green Areas Shape Public Health and Environmental Awareness in Istanbul

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

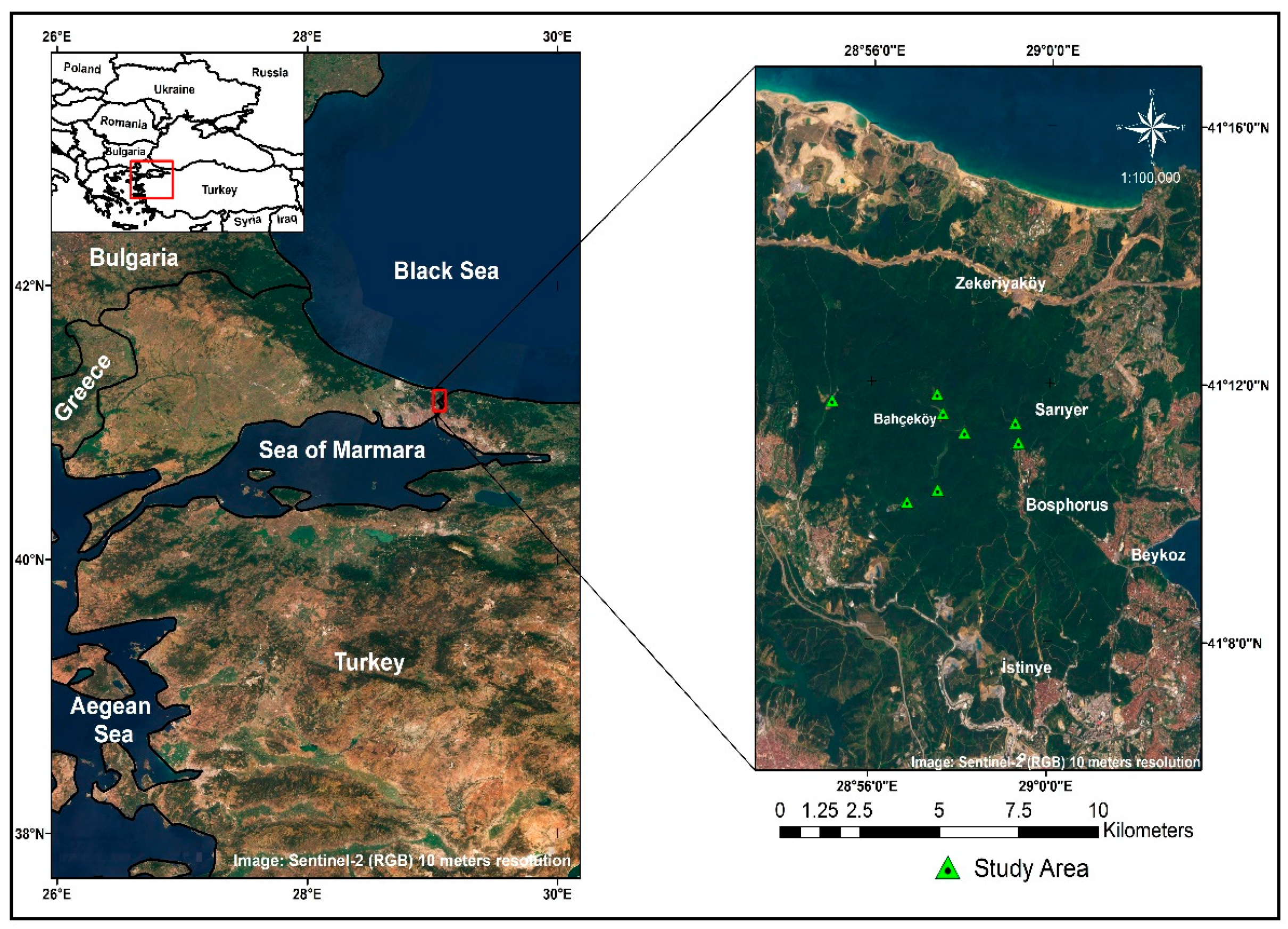

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey Design and Participants

2.3. Questionnaire Design and Structure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics and Spatial Distribution

3.2. Participant Green Space Use

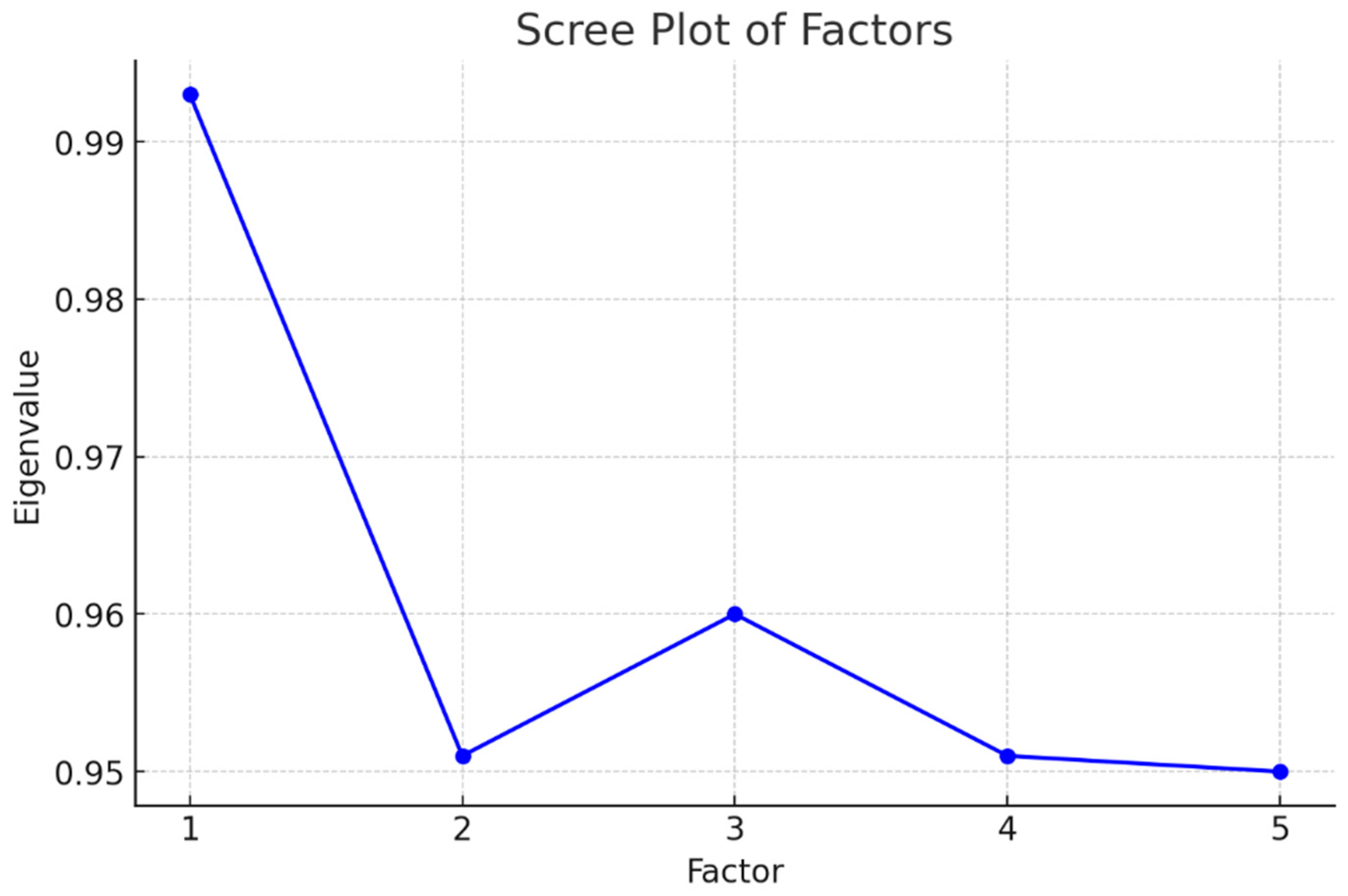

3.3. Factor Analysis Results

3.4. Thematic Interpretation of Factors

3.4.1. Factor 1: Personal Benefit and Well-Being

3.4.2. Factor 2: Energy and Concentration

3.4.3. Factor 3: Urban Green Area Experience

3.4.4. Factor 4: Green Area Use and Activities

3.4.5. Factor 5: Environmental Concern and Value

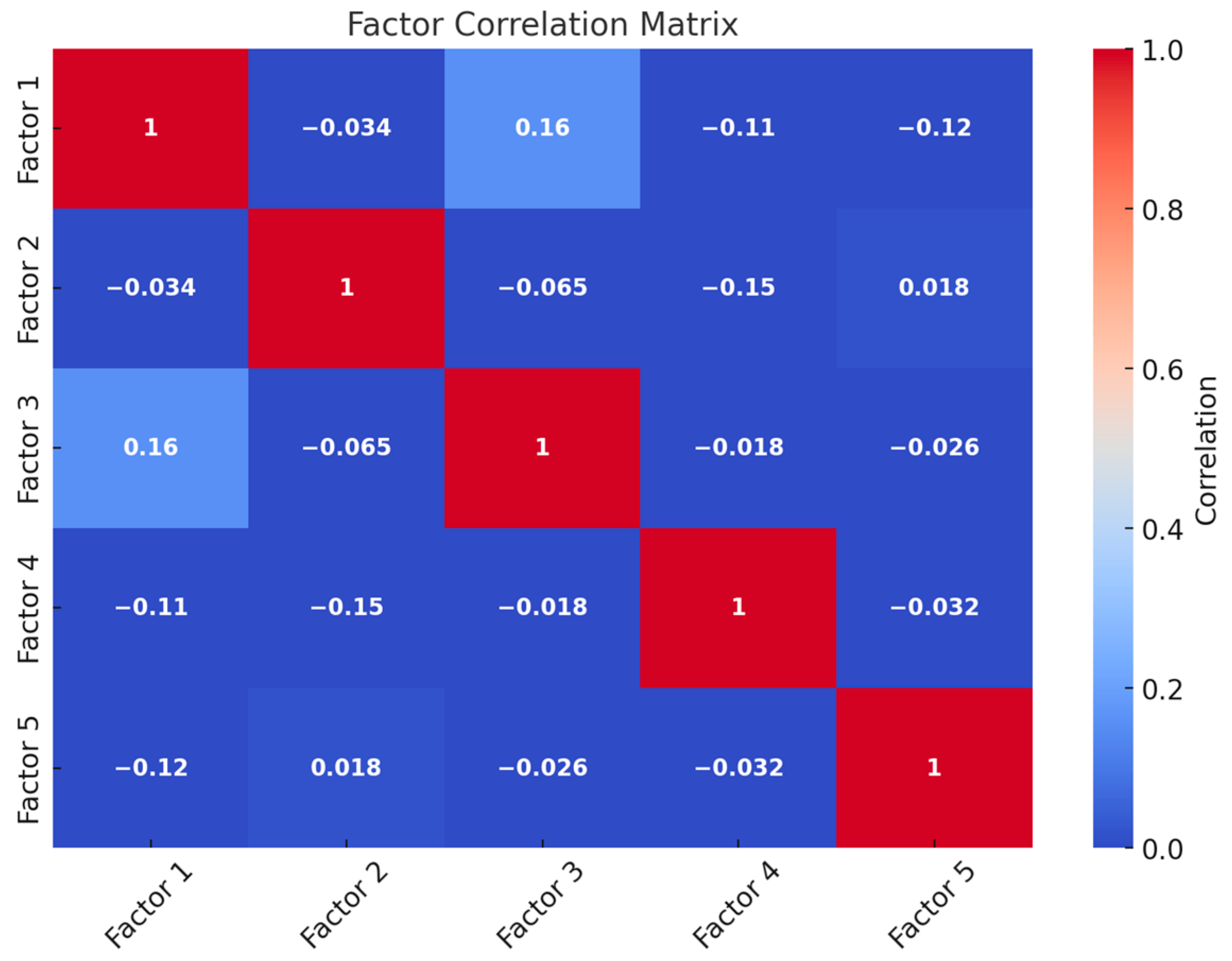

3.5. Relationships Among Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact on Public Health

4.2. Environmental Awareness and Sustainable Behaviors

4.3. Experience and Management of Urban Green Areas

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atanur, G.; Mirici, M.E.; Ersöz, N.D. Kaybolan Kent ve Doğa İlişkisini Kentsel Açık Yeşil Alanlar Üzerinden Tartışmak: Bursa Yıldırım İlçesi Örneği. IDEALKENT 2024, 16, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Setälä, H.; Handel, S.N.; van der Ploeg, S.; Aronson, J.; Blignaut, J.N.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Nowak, D.J.; Kronenberg, J.; de Groot, R. Benefits of restoring ecosystem services in urban areas. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaa, L.; Atalay, A.; Makutėnienė, D.; Perkumienė, D.; Bouazzaoui, I.E. Assessment of carbon footprint negative effects for nature in international traveling. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abass, K.; Serbeh, R. Public perceptions of the health benefits of green spaces in urban Ghana. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Buffoli, M.; Capasso, L.; Fara, G.; Rebecchi, A.; Capolongo, S. Green areas and public health: Improving wellbeing and physical activity in the urban context. Epidemiol. E Prev. 2015, 39, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, T.; Carver, A.; Koohsari, M.; Veitch, J. Advantages of public green spaces in enhancing population health. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 178, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Fluehr, J.; McKeon, T.; Branas, C. Urban Green Space and Its Impact on Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, P.Y.; Richards, D. Relative importance of quantitative and qualitative aspects of urban green spaces in promoting health. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 213, 104131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.Q.; Rhodes, R.E. The pathways linking objectively-measured greenspace exposure and mental health: A systematic review of observational studies. Environ. Res. 2021, 198, 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; De Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T. Restoration in nature: Beyond the conventional narrative. In Nature and Psychology: Biological, Cognitive, Developmental, and Social Pathways to Well-Being; Springer: Cham, Swizerland, 2021; pp. 89–151. [Google Scholar]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Hartig, T.; Putra, I.G.N.E.; Walsan, R.; Dendup, T.; Feng, X. Green space and loneliness: A systematic review with theoretical and methodological guidance for future research. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 847, 157521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space: An avenue for health promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, M.; Beenackers, M.A.; van Timmeren, A.; Pottgiesser, U. Preferred reporting items in green space health research. Guiding principles for an interdisciplinary field. Environ. Res. 2023, 228, 115893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Markevych, I.; Hartig, T.; Tilov, B.; Arabadzhiev, Z.; Stoyanov, D.; Gatseva, P.; Dimitrova, D.D. Multiple pathways link urban green-and bluespace to mental health in young adults. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Browning, M.H.; Markevych, I.; Hartig, T.; Lercher, P. Analytical approaches to testing pathways linking greenspace to health: A scoping review of the empirical literature. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Green and Blue Spaces and Mental Health: New Evidence and Perspectives for Action; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Urban Green Spaces and Health; Document Number: WHO/EURO:2016-3352-43111-60341; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.B.; Fuller, R.A.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Shanahan, D.F. Opportunity or orientation? Who uses urban parks and why. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haluza, D.; Ortmann, J.; Lazic, T.; Hillmer, J. Urban Gardening and Public Health—A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, H.T.; Yıldızbaş, N.T.; Uyar, Ç.; Elvan, O.D.; Sousa, H.F.P.E.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Perkumienė, D. Visitors’ Perceptions towards the Sustainable Use of Forest Areas: The Case of Istanbul Belgrade Nature Parks. Forests 2024, 15, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, Ü.; Elvan, O.D.; Aydın, A.; Perkumienė, D.; Škėma, M.; Aleinikovas, M. Property Rights for Forest Carbon: A Conceptual Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škėma, M.; Doftartė, A.; Perkumienė, D.; Aleinikovas, M.; Perkumas, A.; Sousa, H.F.P.E.; Pimenta Dinis, M.A.; Beriozovas, O. Development of a Methodology for the Monitoring of Socio-Economic Indicators of Private Forest Owners towards Sustainable Forest Management: The Case of Lithuania. Forests 2024, 15, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvan, O.D.; Yıldırım, H.T.; Birben, Ü. Public participation in decision-making processes in the planning for nature parks: The case of Istanbul’s Belgrad Forest. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Z. Yeni Türk Ceza Kanunu, Gerekçe ve Tutanaklarla; Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2004; ISBN 975-347-868-2. [Google Scholar]

- Geray, U.; Şafak, İ.; Yılmaz, E.; Kiracıoğlu, Ö.; Başar, H. İzmir İlinde Orman Kaynaklarına İlişkin İşlev Önceliklerinin Belirlenmesi; Müdürlük Yayın No: 46, Teknik Bülten No: 35; Ege Ormancılık Araştırma Müdürlüğü: İzmir, Turkey, 2007; p. 137.

- Pak, M.; Berber, H. Orman Kaynaklarının İşlevlerine İlişkin Toplumsal Bilinç Düzeyinin İncelenmesi: Eskişehir Ili Örneği. Artvin Çoruh Üniversitesi Orman Fakültesi Derg. 2011, 12, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Shah, A.M.; Lv, B.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Song, H.; Chen, Q. Decoding the Role of Urban Green Space Morphology in Shaping Visual Perception: A Park-Based Study. Land 2025, 14, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, B.; Zeng, C.; Xie, S.; Li, D.; Lin, W.; Li, N.; Jiang, M.; Liu, S.; Chen, Q. Benefits of a three-day bamboo forest therapy session on the psychophysiology and immune system responses of male college students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature contact and human health: A research agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, M.J.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Esnaola, J.; Forns, X.; Basagaña, M.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, I.; Rivas, M.; López-Vicente, M.; De Castro Pascual, M.; Su, J.; et al. Sunyer, Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7937–7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbrenner, H.; Breithut, J.; Hebermehl, W.; Kaufmann, A.; Klinger, T.; Palm, T.; Wirth, K. “The forest has become our new living room”—The critical importance of urban forests during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 672909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoo, K.S.; Karam, D.S.; Abdu, A.; Rosli, Z.; Gerusu, G.J. Addressing psychosocial issues caused by the COVID-19 lockdown: Can urban greeneries help? Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maury-Mora, M.; Gómez-Villarino, M.T.; Varela-Martínez, C. Urban green spaces and stress during COVID-19 lockdown: A case study for the city of Madrid. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes Hursh, S.; Perry, E.; Drake, D. What informs human–nature connection? An exploration of factors in the context of urban park visitors and wildlife. People Nat. 2024, 6, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Mavoa, S.; Villanueva, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Badland, H.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Owen, N.; Giles-Corti, B. Public open space, physical activity, urban design and public health: Concepts, methods and research agenda. Health Place 2015, 33, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençay, G.; Birben, Ü. Striving for sustainability: Climate-Smart Forestry measures in Türkiye. Int. For. Rev. 2024, 26, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Deschacht, N. Public awareness of nature and the environment during the COVID-19 crisis. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, A.; Perkumiene, D.; Aleinikovas, M.; Škėma, M. Clean and sustainable environment problems in forested areas related to recreational activities: Case of Lithuania and Turkey. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1224932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkumienė, D.; Atalay, A.; Safaa, L.; Grigienė, J. Sustainable waste management for clean and safe environments in the recreation and tourism sector: A case study of Lithuania, Turkey and Morocco. Recycling 2023, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamhour, O.; El Bouazzaoui, I.; Perkumiené, D.; Safaa, L.; Aleinikovas, M.; Škėma, M. Groundwater and Tourism: Analysis of Research Topics and Trends. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, E.; Spano, G.; Tinella, L.; Lopez, A.; Clemente, C.; Bosco, A.; Caffò, A.O. Perceived social support mediates the relationship between use of greenspace and geriatric depression: A cross-sectional study in a sample of south-Italian older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, D.G.; Teixeira, C.P.; Fernandes, C.O.; Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Dias, R.C.; Vilaça, H.; Barros, N.; Maia, R.L. Patterns of human behaviour in public urban green spaces: On the influence of users’ profiles, surrounding environment, and space design. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Dutta, A.; Fischer, H.W.; Saxena, A.K.; Jantz, P. Forest livelihoods and a “green recovery” from the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights and emerging research priorities from India. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Leonardo, M.; Rowe, F.; Fresolone-Caparrós, A. Rural revival? The rise in internal migration to rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic: Who moved and Where? J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 96, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandal, E.K.; Karademir, N. Determination of people’s expectations and consciousness with adequacy of green spaces in Kahramanmaraş. East. Geogr. Rev. 2013, 18, 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ertz, M.; Sarigöllü, E. The behavior-attitude relationship and satisfaction in proenvironmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 1106–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevych, I.; Schoierer, J.; Hartig, T.; Chudnovsky, A.; Hystad, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; De Vries, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Brauer, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Subgroups/Groups | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| District | Eyüpsultan/Sarıyer | 53.3/46.8 |

| Gender | Female/Male | 68.2/31.8 |

| Age | 18–30/31–50/51–65/65+ | 37.8/26.5/3.5/32.3 |

| Education | ≤High School/Associate Degree/≥Bachelor’s Degree | 39.2/26.5/34.3 |

| Occupation | Public sector Private sector/Retired/Other | 46.5/22.0/2.3/29.3 |

| Household income | Low/Lower–middle/Upper–middle/High | 39.0/24.5/3.8/32.8 |

| Category | Subgroups/Groups | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Weekly Duration | <1 h/1–2 h/2–3 h/3–4 h/>4 h | 3.0/6.5/13.0/69.8/7.5 |

| Main Activity | Walking, running, or biking/Resting/Exercising/Picnic/Playing/Pet walking/Reading | 11.3/1.3/2.5/0/1 |

| Visit for Stress? | Yes/No/Sometimes | 80.0/10.8/9.0 |

| Feeling After Visit | More relaxed/Less stressed/More energetic/More peaceful | 8.2/11.0/4.8/13.8/13.5/6.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yıldızbaş, N.T.; Gençay, G.; Birben, Ü.; Oskay, F.; Perkumienė, D.; Škėma, M.; Aleinikovas, M. Benefits Beyond the Physical: How Urban Green Areas Shape Public Health and Environmental Awareness in Istanbul. Forests 2025, 16, 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16050786

Yıldızbaş NT, Gençay G, Birben Ü, Oskay F, Perkumienė D, Škėma M, Aleinikovas M. Benefits Beyond the Physical: How Urban Green Areas Shape Public Health and Environmental Awareness in Istanbul. Forests. 2025; 16(5):786. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16050786

Chicago/Turabian StyleYıldızbaş, Nilay Tulukcu, Gökçe Gençay, Üstüner Birben, Funda Oskay, Dalia Perkumienė, Mindaugas Škėma, and Marius Aleinikovas. 2025. "Benefits Beyond the Physical: How Urban Green Areas Shape Public Health and Environmental Awareness in Istanbul" Forests 16, no. 5: 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16050786

APA StyleYıldızbaş, N. T., Gençay, G., Birben, Ü., Oskay, F., Perkumienė, D., Škėma, M., & Aleinikovas, M. (2025). Benefits Beyond the Physical: How Urban Green Areas Shape Public Health and Environmental Awareness in Istanbul. Forests, 16(5), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16050786