1. Background

With over 1600 species worldwide [

1], bamboos are a sub-family of self-propagating grasses, representing a key non-timber forest product (NTFP) in many tropic and sub-tropic regions [

2]. Most large timber bamboo species are fast growing and can sequester and store large amounts of carbon in a short time [

3]. For example, a single bamboo shoot of

Phyllostachys edulis, common in Asia, can reach maturity and provide harvestable, high-quality bamboo culms in 3–7 years [

4]. Bamboo forests can sequester as much or more carbon than other similar land uses in the tropics including agroforests, rubber plantations, oil palm, and some cash-crop farms [

5,

6]. This potential is linked to the fact that bamboo can be harvested yearly without killing the plant, regenerating many times over its lifespan [

7]. There is also a wealth of evidence supporting bamboo species’ ability to thrive in degraded landscapes such as mining sites [

8]. It has been used successfully in a variety of land restoration projects [

9]. It is often used as part of a landscape mosaic approach [

10] to regenerate and protect soil against erosion [

11], to break up densely compacted soil to promote regrowth, and to help protect water sources and increase water quality [

12]. After appropriate treatment, the physical strength and durability of timber bamboo are comparable to those of wood and thus have the potential to decrease pressure on existing timber resources and reduce deforestation [

13].

Among other sources of locally abundant natural fiber, bamboo is of particular interest to many as a tool for livelihood development [

14]. Many bamboo species flourish in rural parts of the Global South [

15], close to some of the world’s most vulnerable human populations. Bamboo plays an important role in the daily lives and traditional practices of many cultures [

16,

17], both historically and at present [

18]. Bamboo can be made into thousands of different types of goods ranging from lower-cost daily use items, alternatives for plastic [

19], and artisanal crafts to strong load-bearing beams in houses [

20], and even high-end furniture [

21]. Due to these unique properties and versatility, some stakeholders have identified bamboo as a crop with high potential for climate-smart, ecologically sustainable income generation in tropical areas [

22]. It has also been identified as a relatively undeveloped global industrial resource, with significant market potential [

23] and potential for integration into future industrial paradigms [

24].

In international development, the commercialization of locally available NTFP is often promoted as an ecologically and economically sound poverty alleviation strategy [

25]. However, this approach is not without criticism in the literature [

26]. Critics have pointed out that many unseen barriers to the commercialization of a crop or product may exist that may impede the process [

27], and that scaling up production often leads to uneven economic opportunities or unsustainable harvesting of the resource, causing an eventual decline in the resource base and widening social inequality [

28].

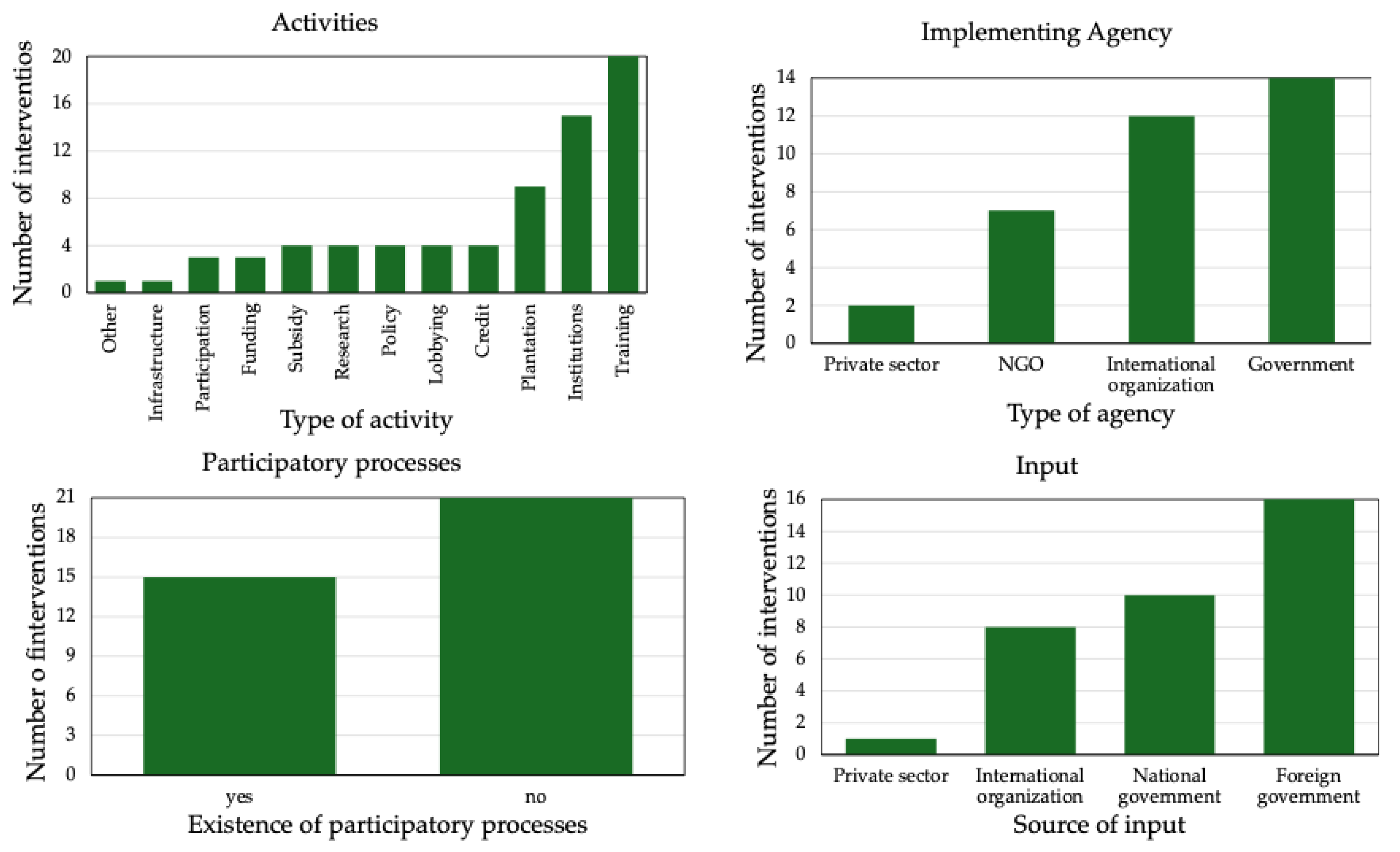

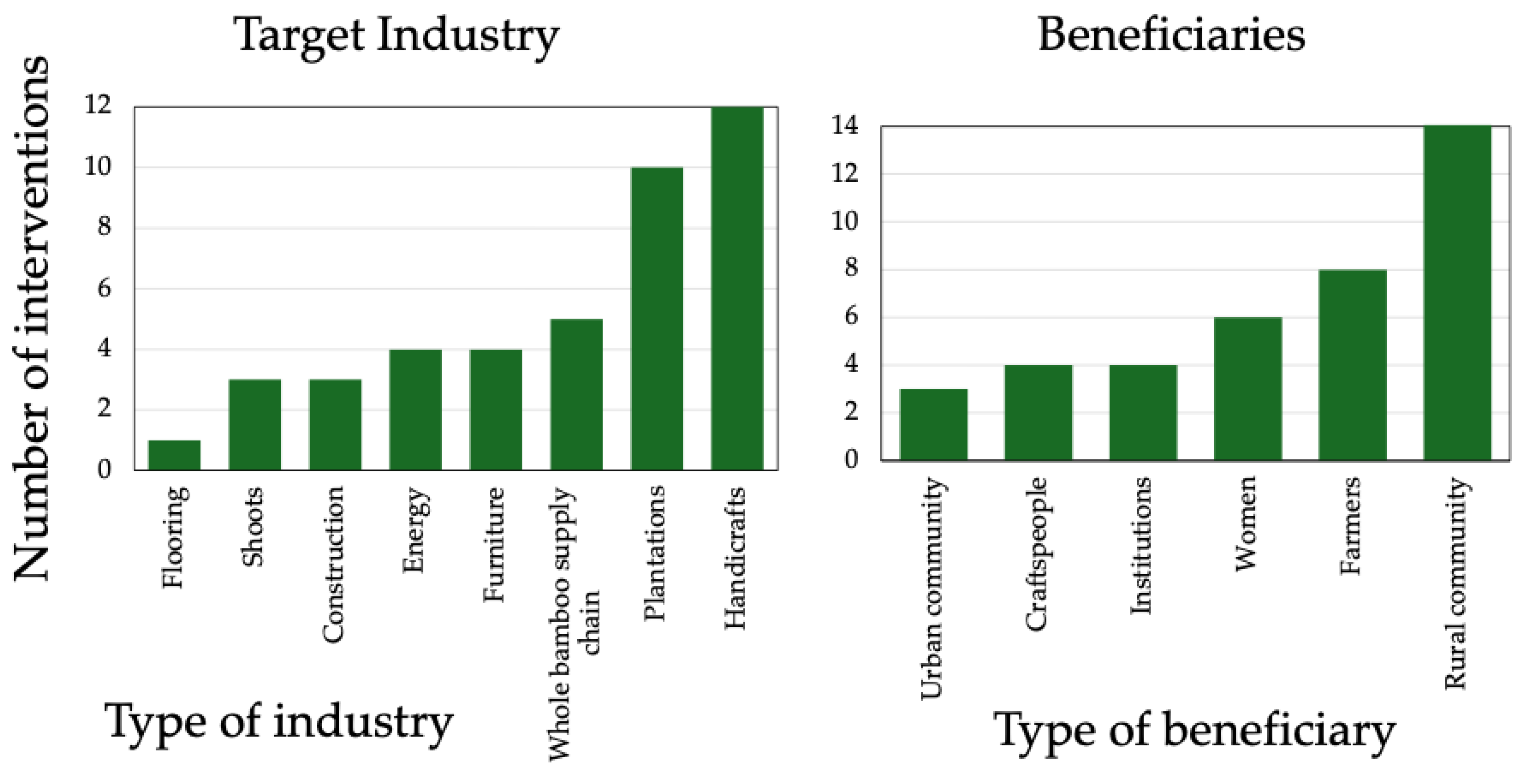

In this context, numerous projects across various countries have been implemented by international development institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and governments, that aim to facilitate the development of a sustainable and thriving bamboo industry. These projects usually combine social and economic objectives such as a desire for increased incomes, the diversification of income sources, or the addition of a stable source of supplementary income for local people, alongside a realm of environmental objectives like carbon sequestration [

29], land restoration [

30], and watershed management [

31]. They generally include a wide range of objectives and activities, typically funded through partnerships between government and non-government entities and implemented by international development organizations, local community organizations, or governments. Examples of activities carried out in this type of project include training participants in bamboo harvesting, management, or processing; policy or regulatory changes to incentivize bamboo industrial development; attempts to develop the natural resource base for future use, which could look like planting bamboo to meet joint environmental and social objectives; and funding for groups or entrepreneurial clusters to invest in equipment or marketing for their growing businesses. Other projects may promote the bamboo industry indirectly through market research. Bamboo fiber has many target applications. The target industry for this type of intervention could therefore include construction, decoration, flooring, furniture, handicrafts, food, or cosmetics. Specific target outcomes and impacts include socio-economic aspects, like income changes, wellbeing, or gender equality, but could also include any other type of outcome. Since bamboo fiber is considered an environmentally friendly and low-carbon material, environmental objectives are often implicit in the project design, with sustainable management of NTFPs such as bamboo often assumed to contribute automatically to many ecosystem services [

32]. Target projects will be referred to henceforth as “interventions”, in keeping with our research question framing.

A systematic evidence map collects and categorizes evidence on a particular topic, summarizing trends and highlighting areas of data-scarce and data-rich evidence availability [

33]. It is a useful method for evidence synthesis in cases such as this in which evidence is scattered and unevenly distributed and the research topic is broad. It can bring together the reported outcomes and impacts of these collective projects and programs, identify major gaps in the public understanding of this approach, and allow for a holistic look at evidence in the field.

This systematic evidence map follows the Campaign for Environmental Evidence (CEE) guidelines for systematic evidence maps [

34]. As part of these guidelines, this review follows a previously published protocol, with deviations as detailed in

Section 2.1 [

35]. A protocol is a document that outlines the rationale, search strategy, and planned reporting methods for a meta-analysis. The purpose of publishing a protocol in advance of a final report is to ensure replicability and transparency, and to solicit feedback on the review methodology from an audience of peers.

As far as we are aware, no attempt has yet been made to systematize evidence in this field. Although these interventions are sometimes discussed in the peer-reviewed literature, much of the information on the interventions in question is found in organizational and grey literature, including in project reports, program evaluations, and summaries. These reports are often published by the organization that has implemented the intervention and may have a significant risk of bias and incentive to obscure negative outcomes [

36]. There is no universal evaluation or reporting methodology for international development projects, although many follow international development norms and participate in external evaluations and auditing practices. Specific standards include those of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Development Assistance Committee [

37] and the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) [

38].

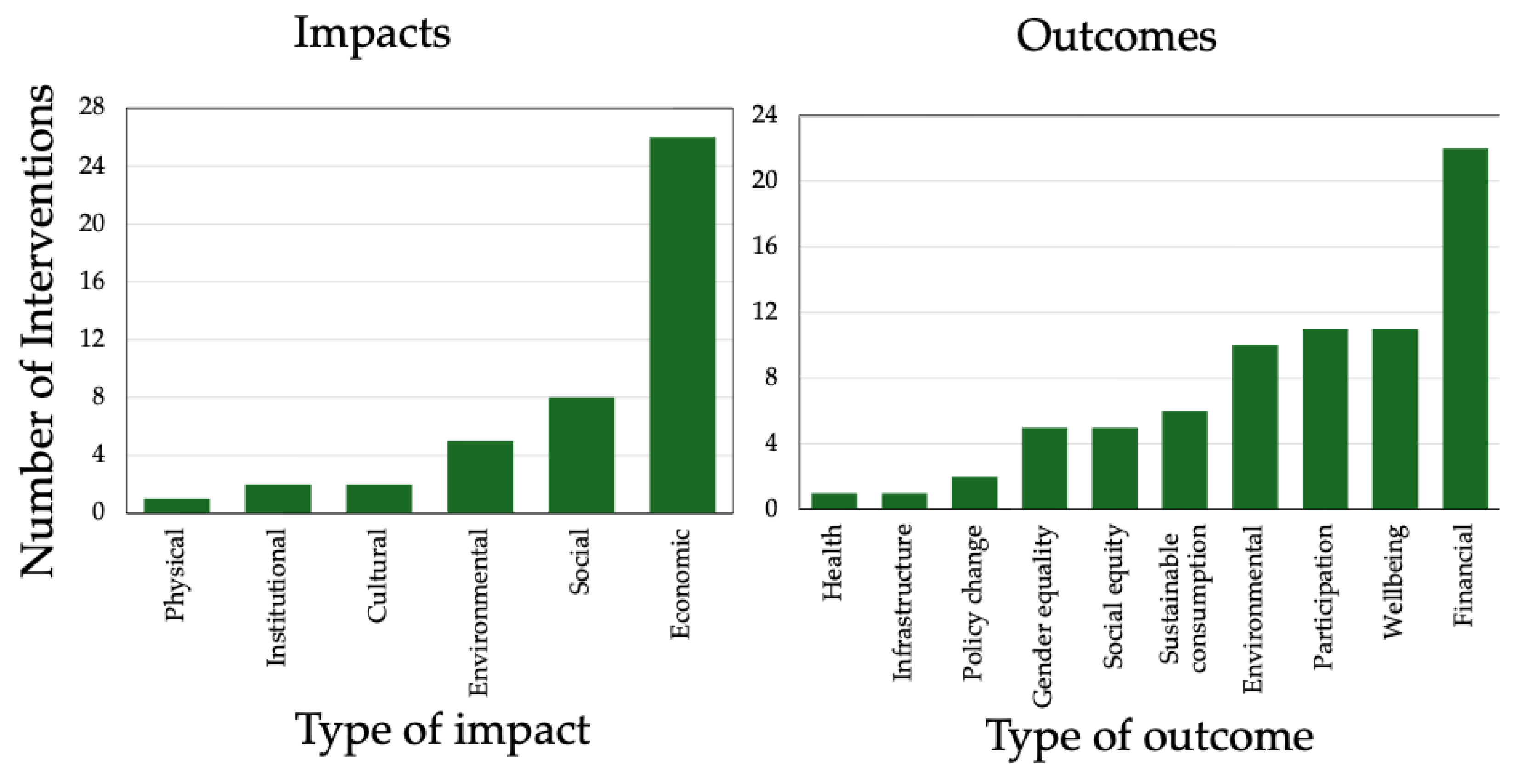

This systematic evidence map looks at evidence on the social, environmental, and economic impacts and outcomes of development interventions that have promoted bamboo for sustainable livelihoods since 1990. This project uses definitions of “outcomes” and “impacts” as defined by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) [

39]. CIFOR defines “outcomes” and “impacts” as qualitatively different types of change, making their categorization in a systematic map database less ambiguous.

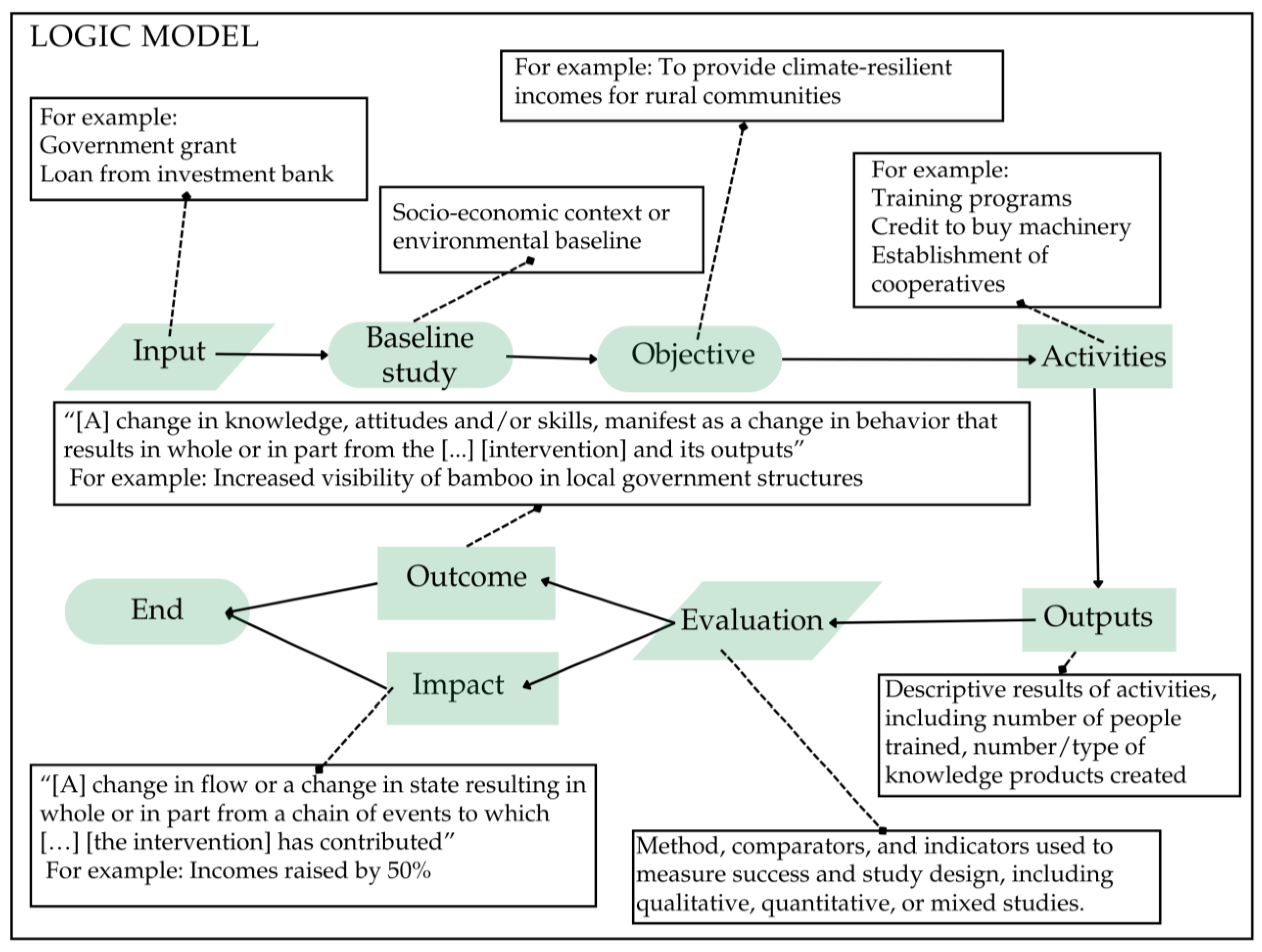

“Outcomes” are defined as “change[s] in knowledge, attitudes and/or skills, manifest as a change in behavior that results in whole or in part from the… [intervention]… and its outputs” [

40]. “Impacts” are here defined as “change[s] in flow or a change in state resulting in whole or in part from a chain of events to which… [the intervention] … has contributed”. Within this framework, impacts often consist of population-level statistics that describe these changes in flow or in state. For example, % change in average income from a baseline would be classed as an impact, whereas individual changes in job title due to skills learnt during training would be classed as outcomes.

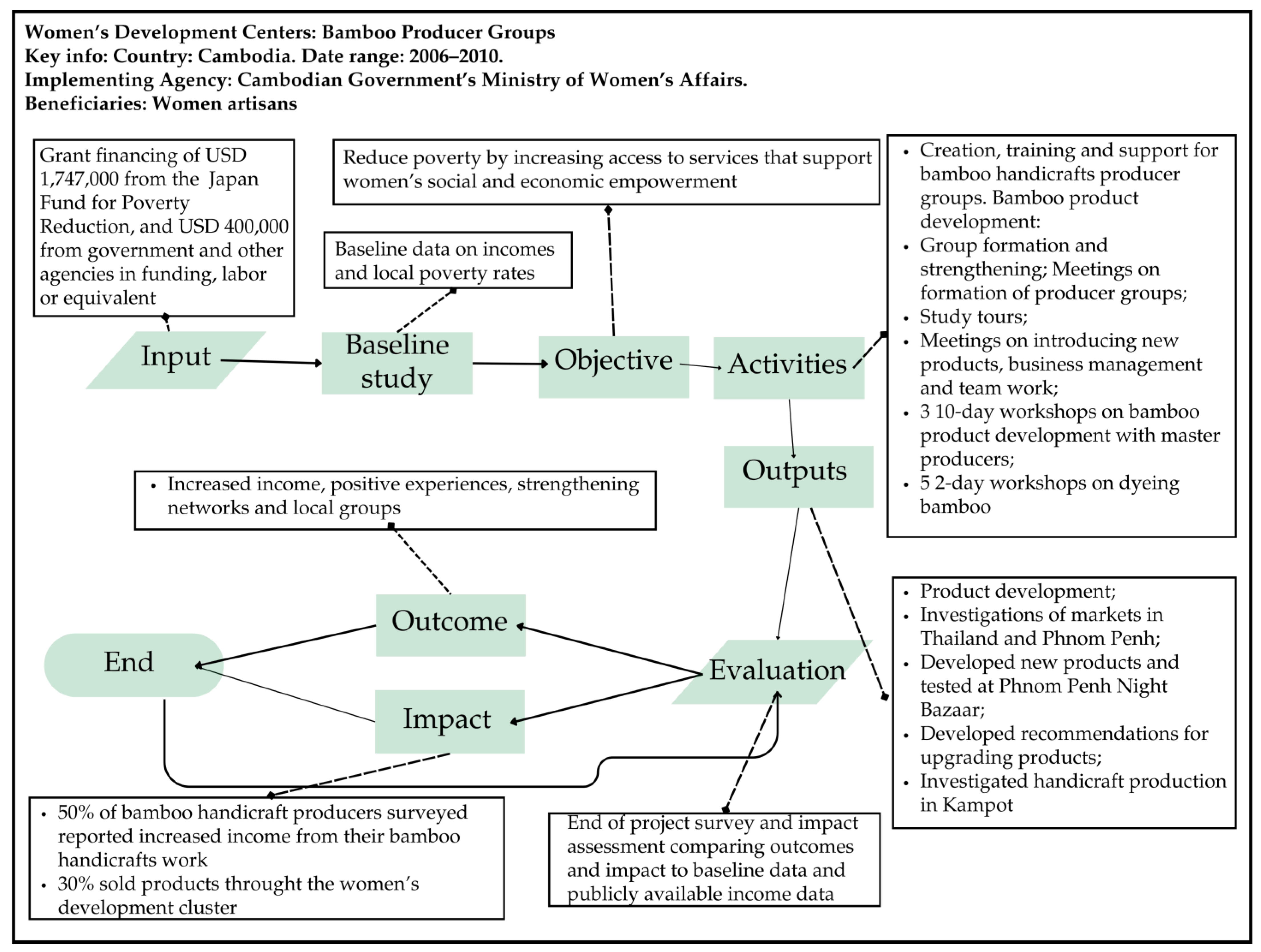

As required by the CEE guidelines for systematic evidence map reports [

34], a generalized logic model [

41] for the type of intervention considered in this review is shown in

Figure 1. Examples for each category are shown to demonstrate how components of this type of project are conceptually linked, and the type of information we are interested in collecting during this systematic evidence-mapping exercise. This logic model presents a simplified casual connection between project funding, activities, outputs, and outcomes and is presented with the understanding that causality between different aspects of real-world projects may not be as simple. To attempt to confirm casual links between desired outcomes and project activities, project managers and evaluation professionals employ a wide range of different methodologies.

1.1. Stakeholder Engagement

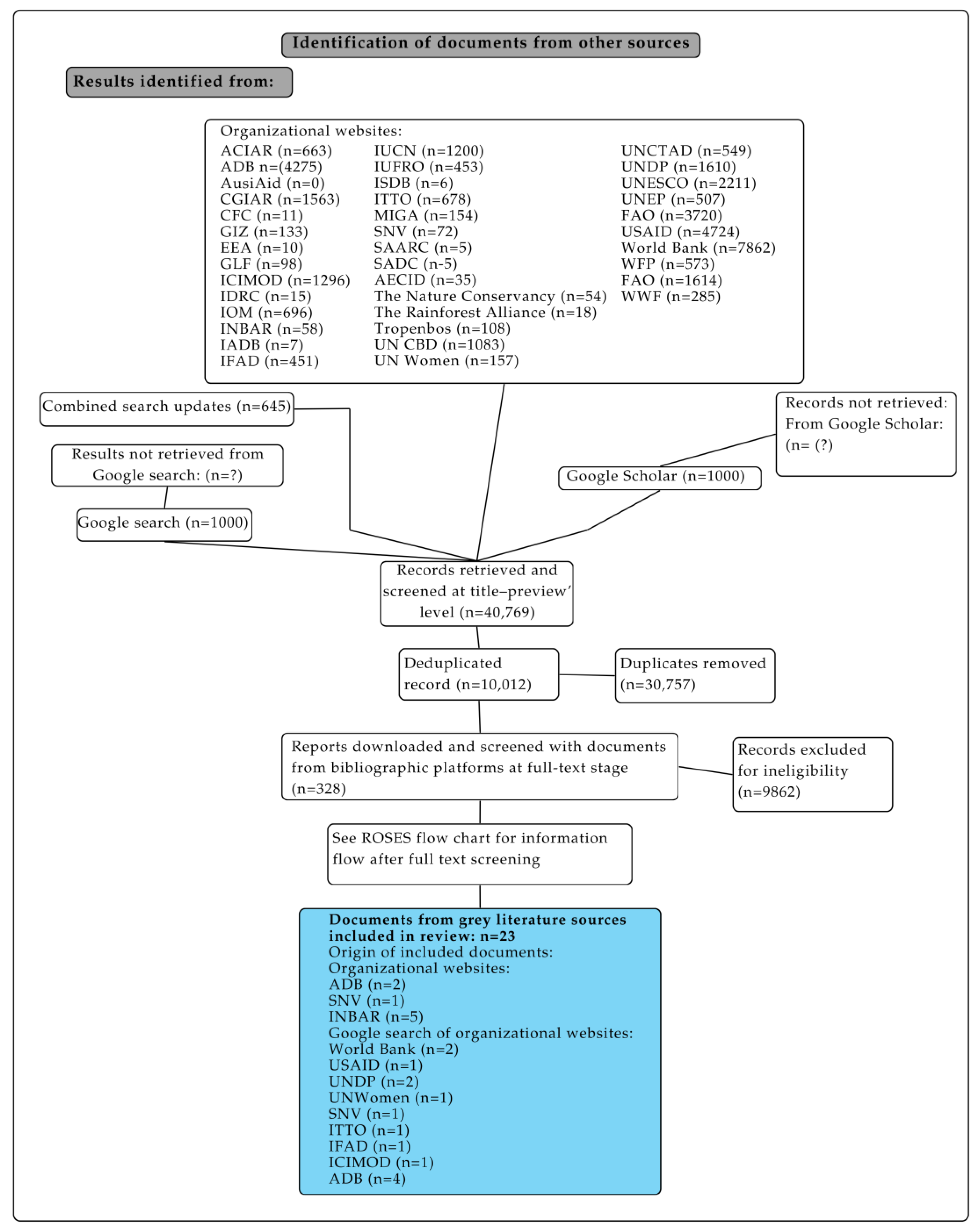

Three expert stakeholders from the World Bamboo Organization, the Forest Stewardship Council, and the International Bamboo and Rattan Organization, and two academics from the University of British Columbia (UBC), were consulted by email to suggest interventions or search sources that were not covered by the protocol. Soliciting supplementary sources from experts did not yield any more search sources, but experts did suggest organizational websites to add to the search for grey literature. Seven search sources were suggested during the stakeholder engagement process.

1.2. Objective of the Review

The primary review question is as follows: What is the evidence on the social, environmental, and economic impact of interventions that facilitate bamboo industry development for sustainable livelihoods? This question was formulated using the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome (PICO) framework for research questions [

42]. PICO components are shown in

Table 1.

Secondary review questions include the following:

4. Discussion and Conclusions

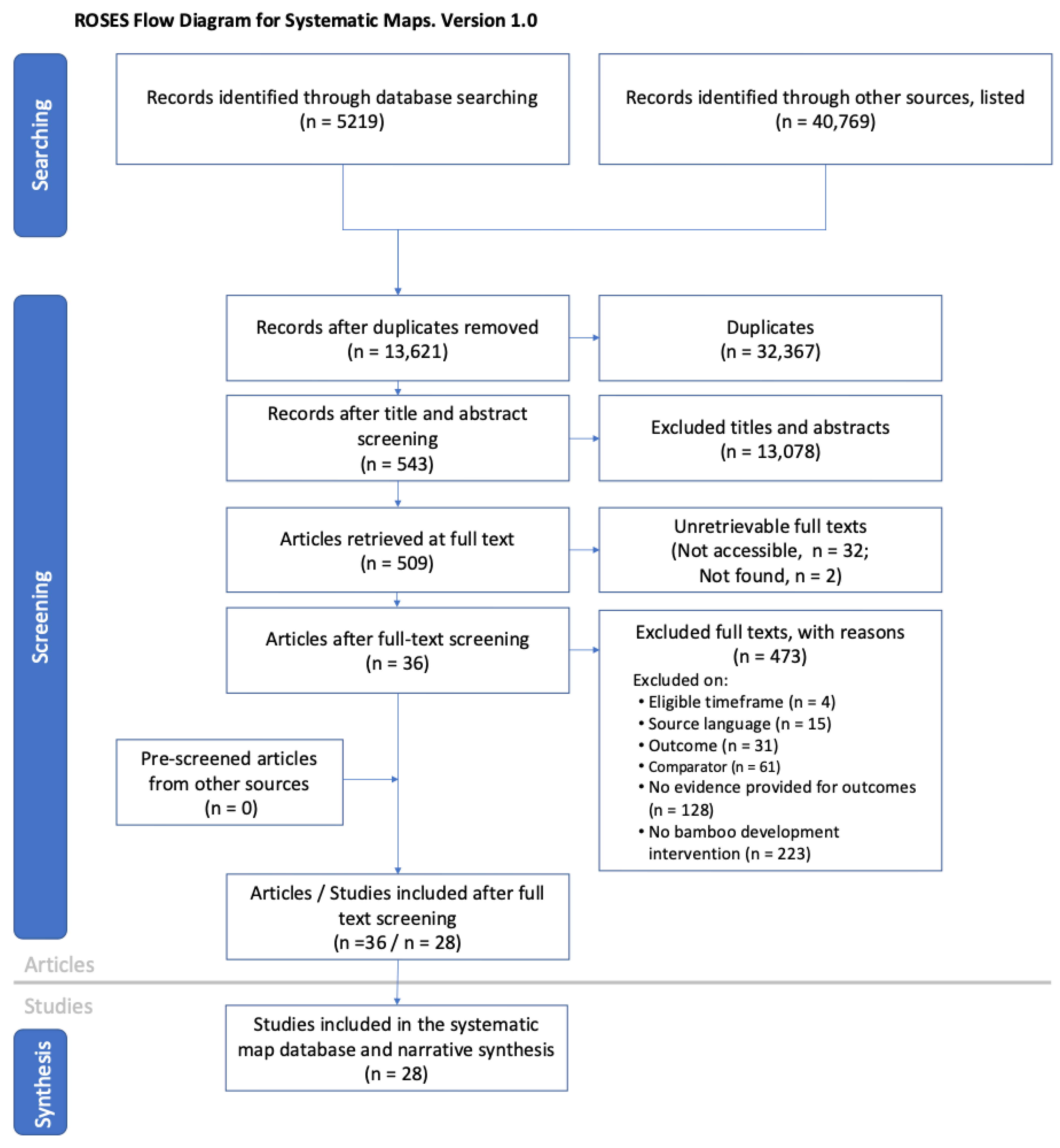

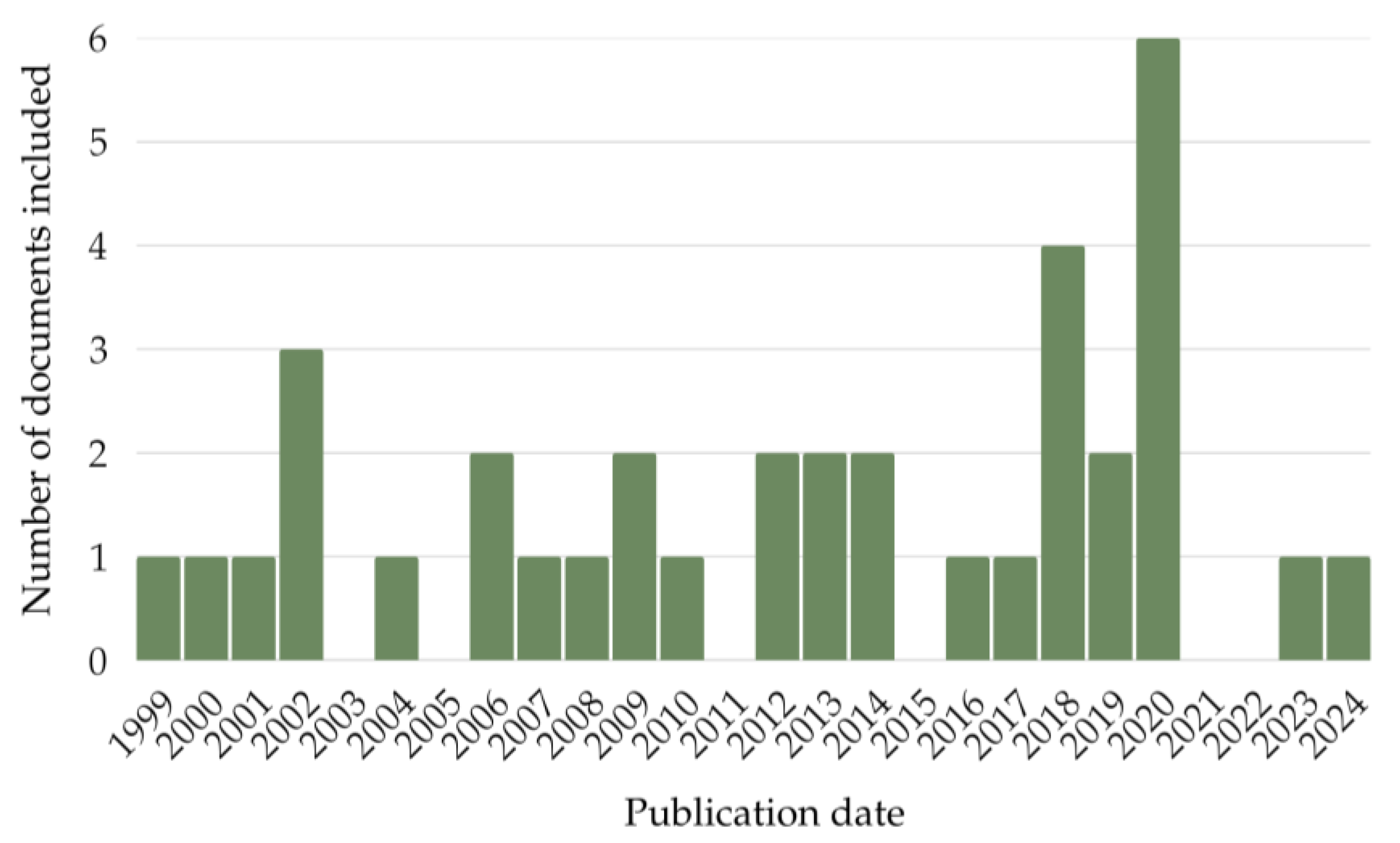

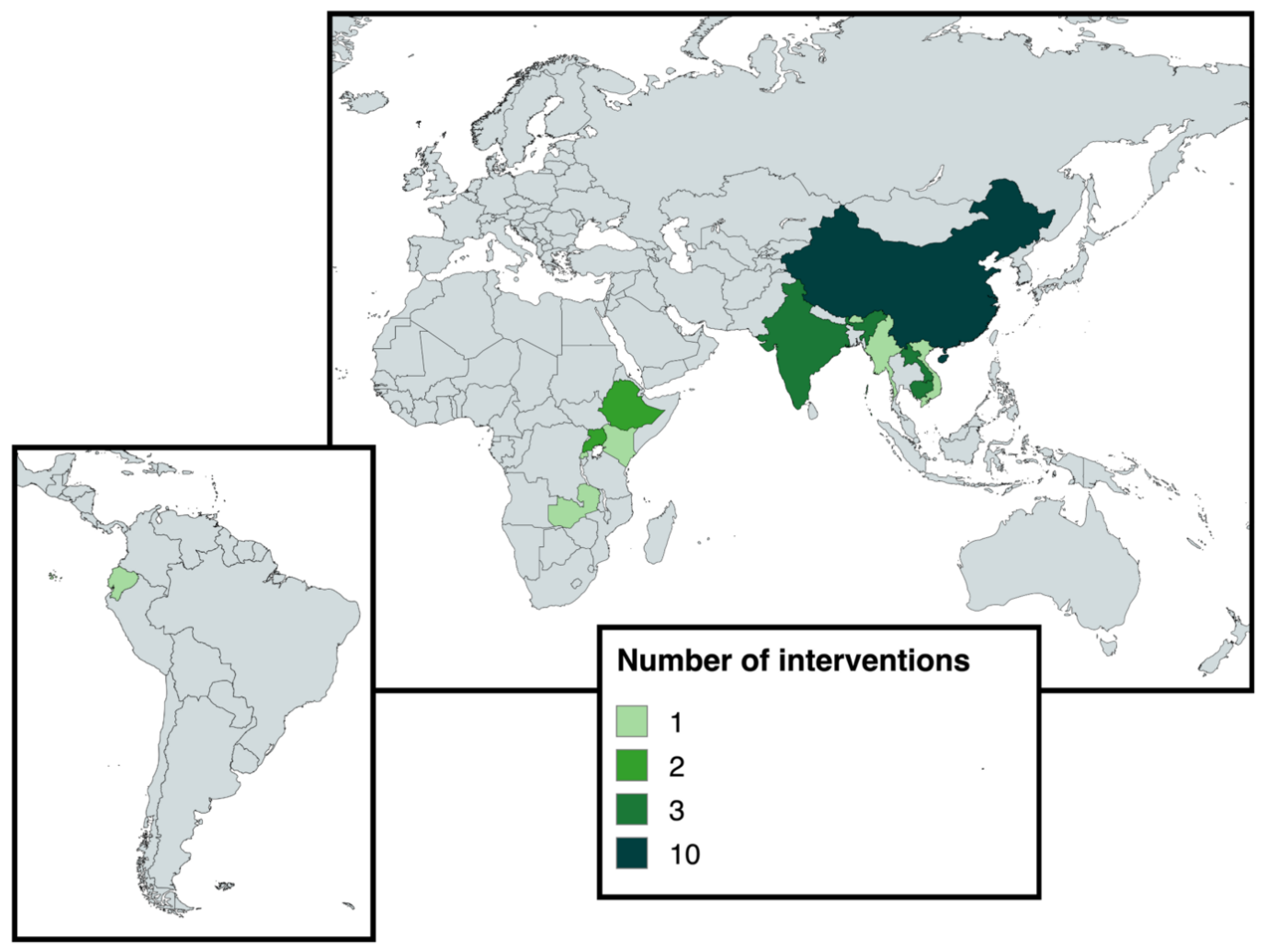

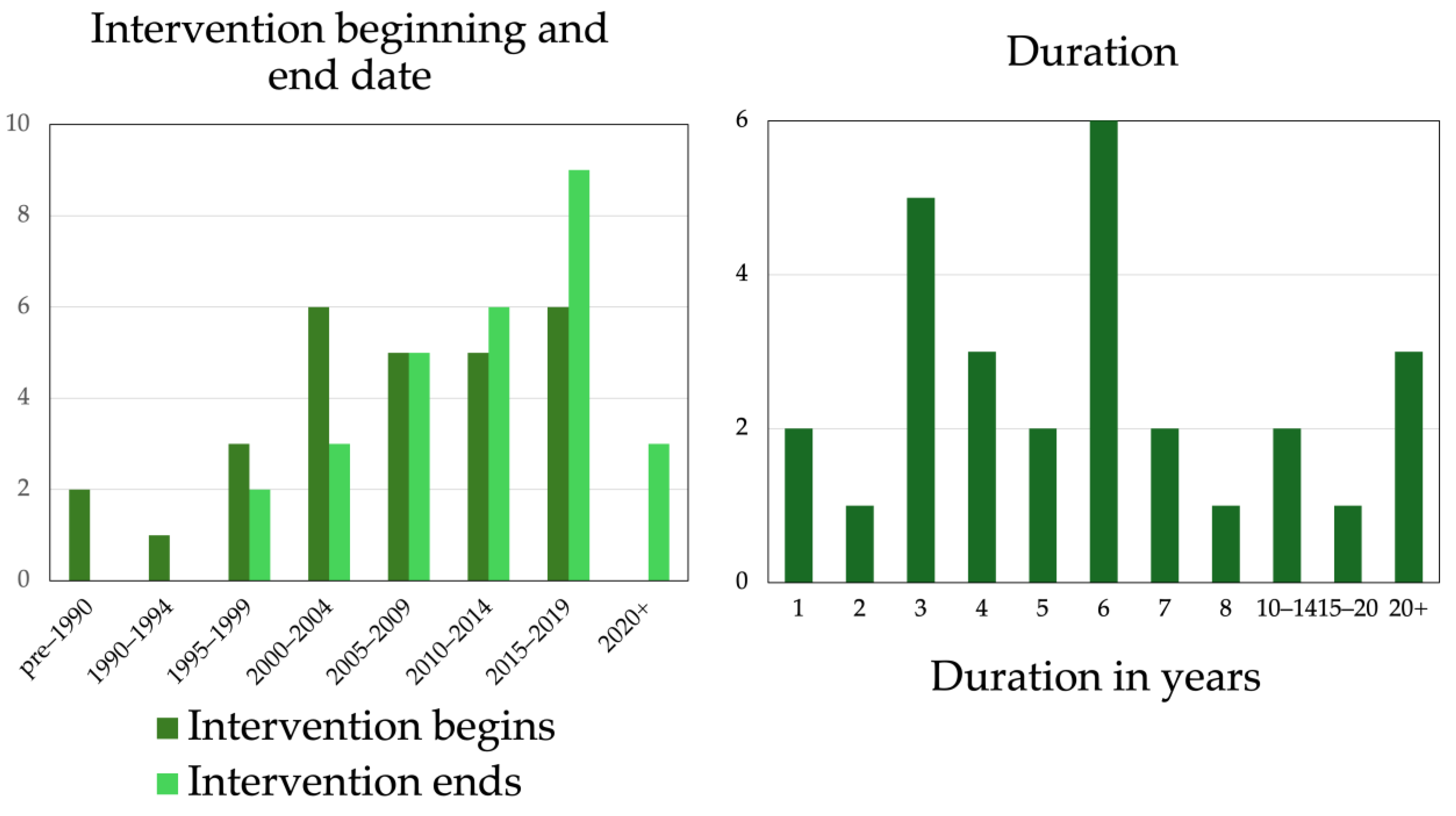

This systematic evidence map adds to the discussion of bamboo as a tool for livelihood development by collecting published evidence on the impact of bamboo development interventions worldwide since 1990. The resulting map is dominated by evidence provided by interventions implemented in China by the Chinese government, comprising 9 out of 28 interventions. A complete appraisal of the evidence is hindered by the large number of “unknown unknowns” in the field, and many interventions were excluded from the map due to a lack of evidence on their impact.

4.1. Implications for Policy/Management

The evidence showed a significant trend towards financial security, as did outcomes focused on economic benefits. These findings are aligned with social science critiques of integrated conservation and development projects [

51] that argue that financial rewards, being easily reported, and compared, are often prioritized at the expense of more intangible impacts related to community values and the intervention’s ethical responsibility to local communities. As few of the interventions recorded provided the long-term data required to sufficiently evaluate any negative social impacts and unintended consequences that might have arisen in response, it is uncertain whether these critiques can be applied to the context of bamboo development or if the financial and other benefits continued and expanded post-intervention. Confounding variables such as economic trends make understanding the true contribution of any intervention to community wellbeing and economic success very difficult.

The systematic map also demonstrates the prevalence of inter-institutional collaborations and foreign investment to fund these interventions, indicating that many national governments in bamboo-producing regions, particularly those outside of China, often lack the financial and technical capacity to grow this industry outside of domestic markets, or may lack the resources to collect and disseminate information on the evidence of the impact of the interventions. Investing in capacity building/training and strengthening local institutions were the most common activities across all 28 interventions, highlighting the perceived importance of human expertise and institutional resources to the bamboo industry.

This systematic map helps to identify areas of opportunity where future investments and interventions can be prioritized by policymakers, donors, and agency staff.

4.2. Implication for Research

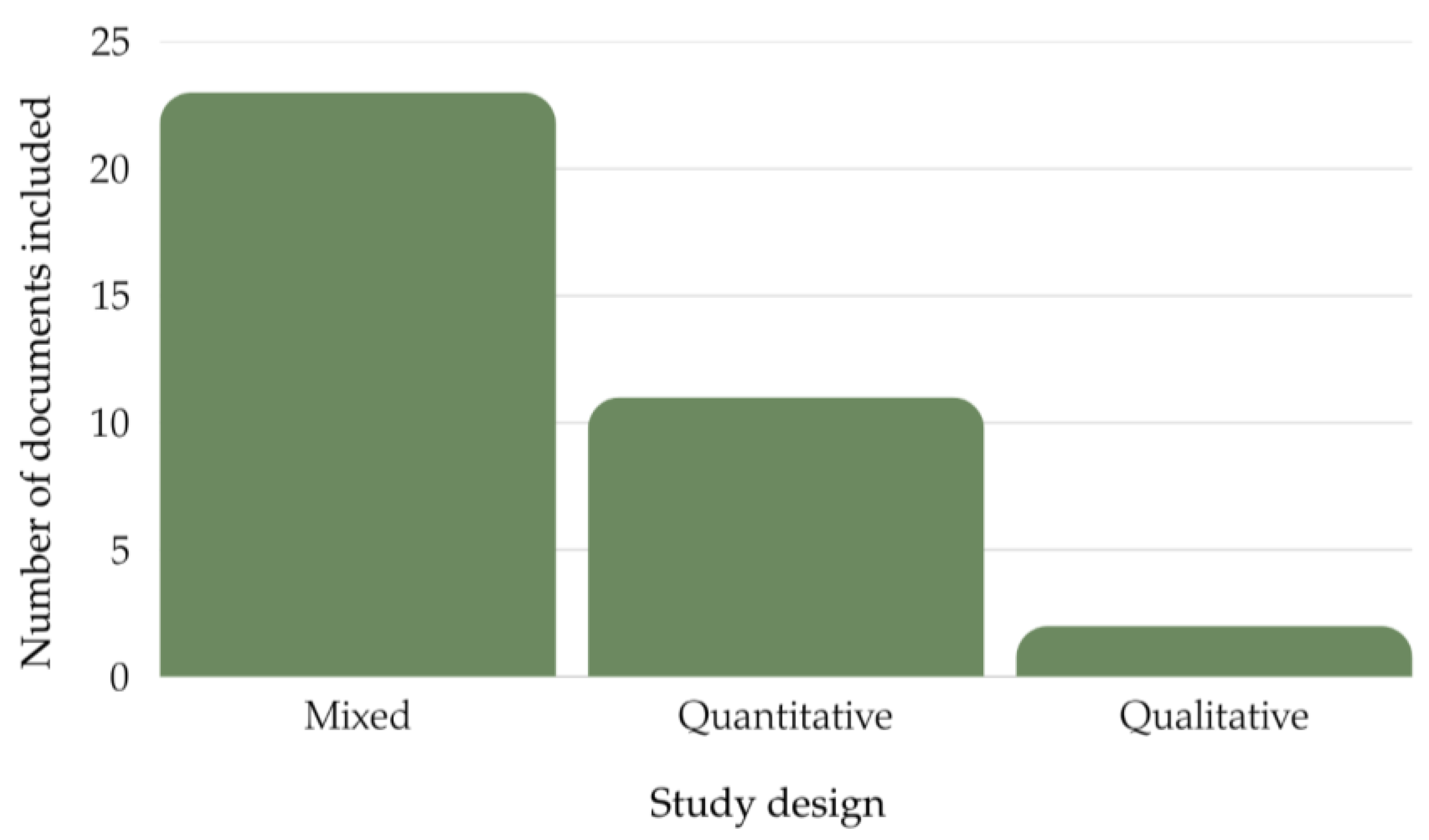

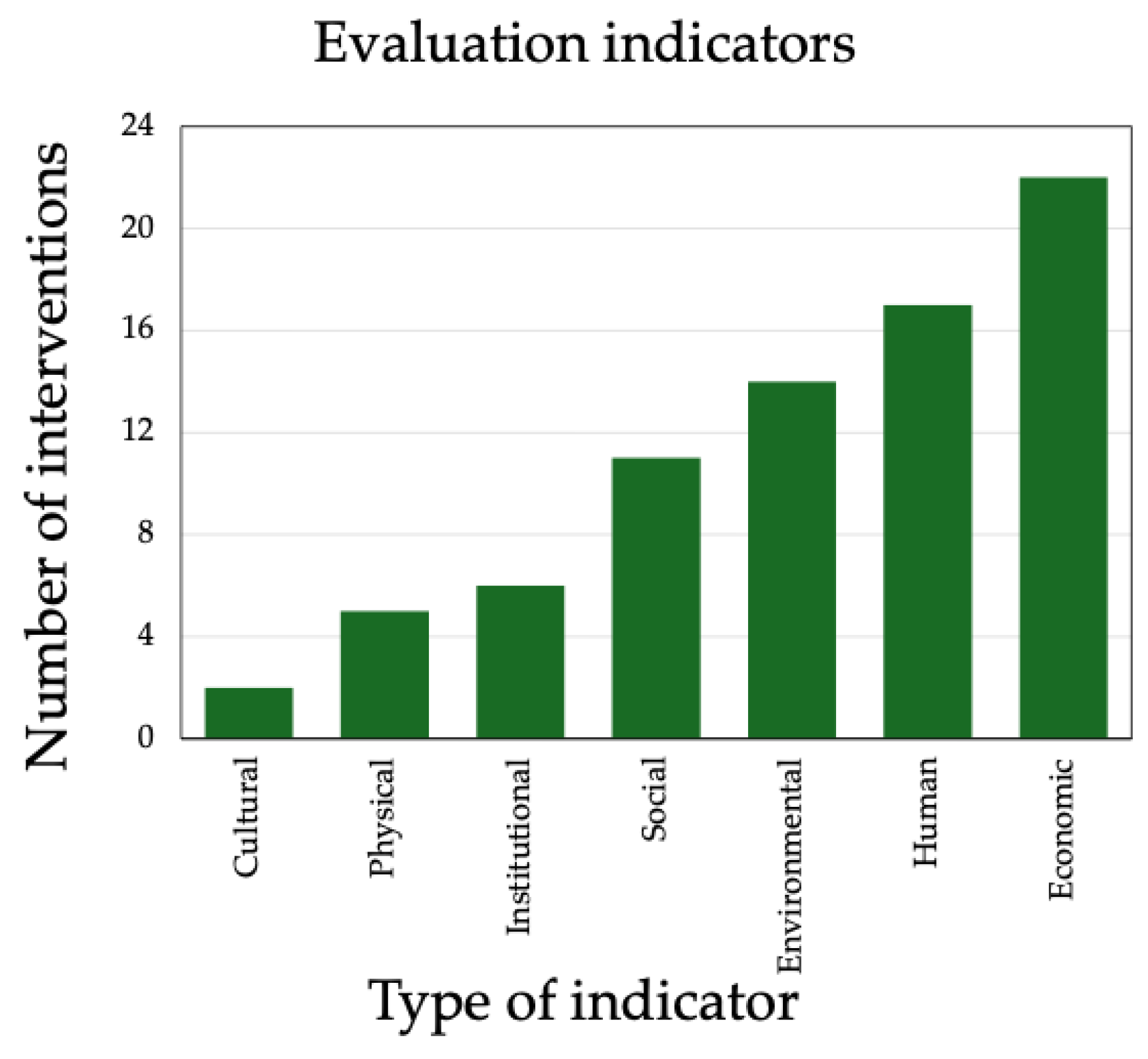

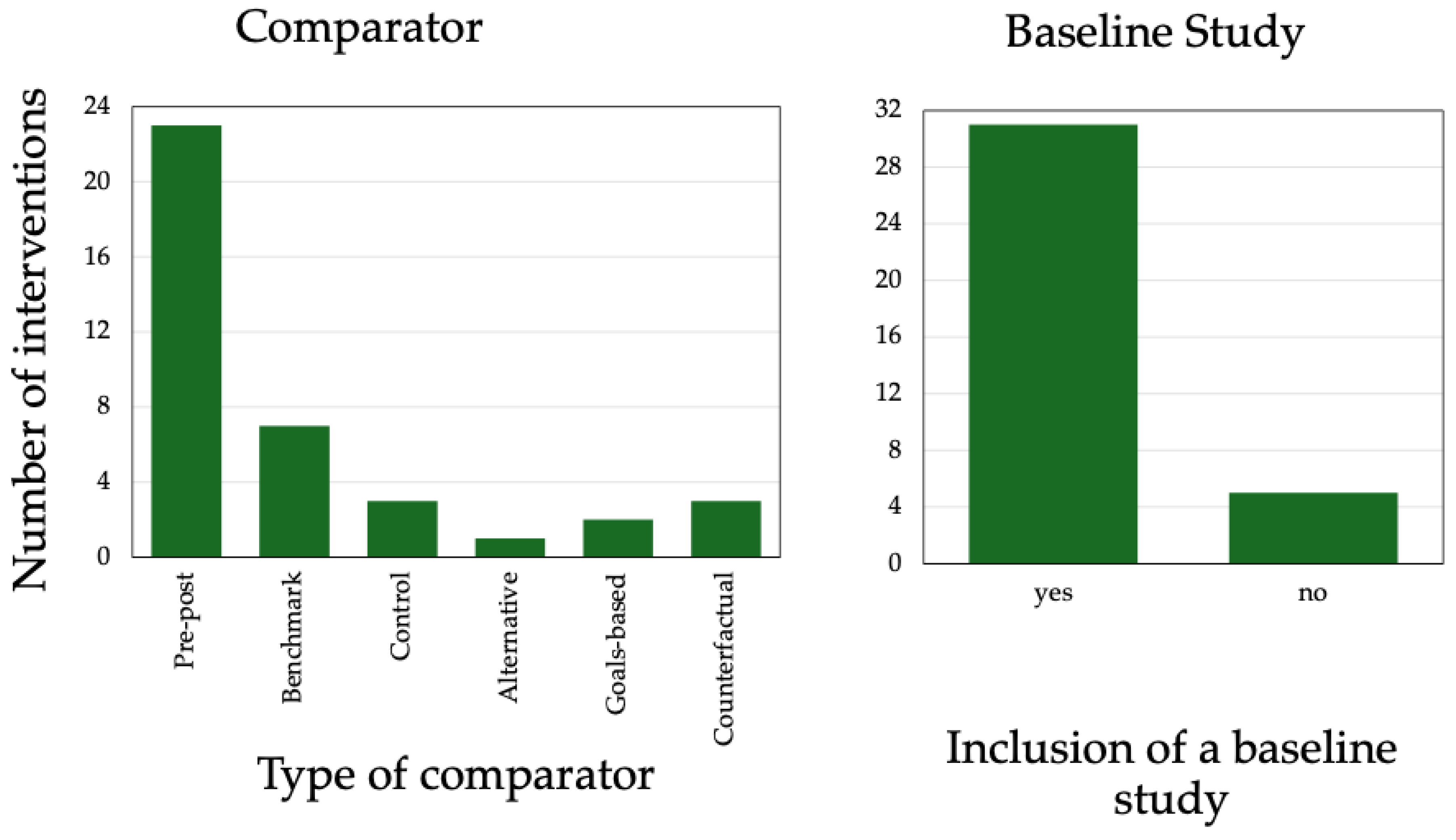

This review found evidence of the outcomes and impact of 28 unique interventions that have carried out activities across a range of industries, reporting outcomes both positive and negative for communities and the environment. Practitioners in the field are motivated to improve lives and create climate-smart value chains using an environmentally friendly and locally abundant material. The dominant type of outcome for which there is evidence is improved incomes and economic impact, with few alternative outcome types recorded in the literature. Further primary research collecting concrete evidence of the impact of more interventions in many areas would be beneficial for the field. The list of excluded records provided with this report can form a starting point for this research, since it provides a record of documents describing interventions for which no evidence of outcomes or impact could be found. We have also provided a list of interventions for which abundant information was found, which could become a starting point for further elaboration of themes, success factors, and theories of change for further research. Further research would also be beneficial in exploring the impact of the interventions included in this database in other areas, such as social equity and gender equality, for which few outcomes were found. In this field, research collecting data using a rigorous comparator, such as a control group similar to the beneficiary group, is particularly difficult. All interventions and beneficiary populations are very different. External factors, such as economic or social trends, can have an outsize impact on the metrics considered to show evidence of impact, such as incomes. This makes comparing and categorizing evidence on impact challenging. Collecting high-quality data is expensive and time consuming for project implementers. Nevertheless, reporting can make evidence synthesis and evidence-based recommendations more accurate by specifically identifying how and from what baseline or control data are collected in publicly available reports, and reporting on negative outcomes and on goals not achieved.

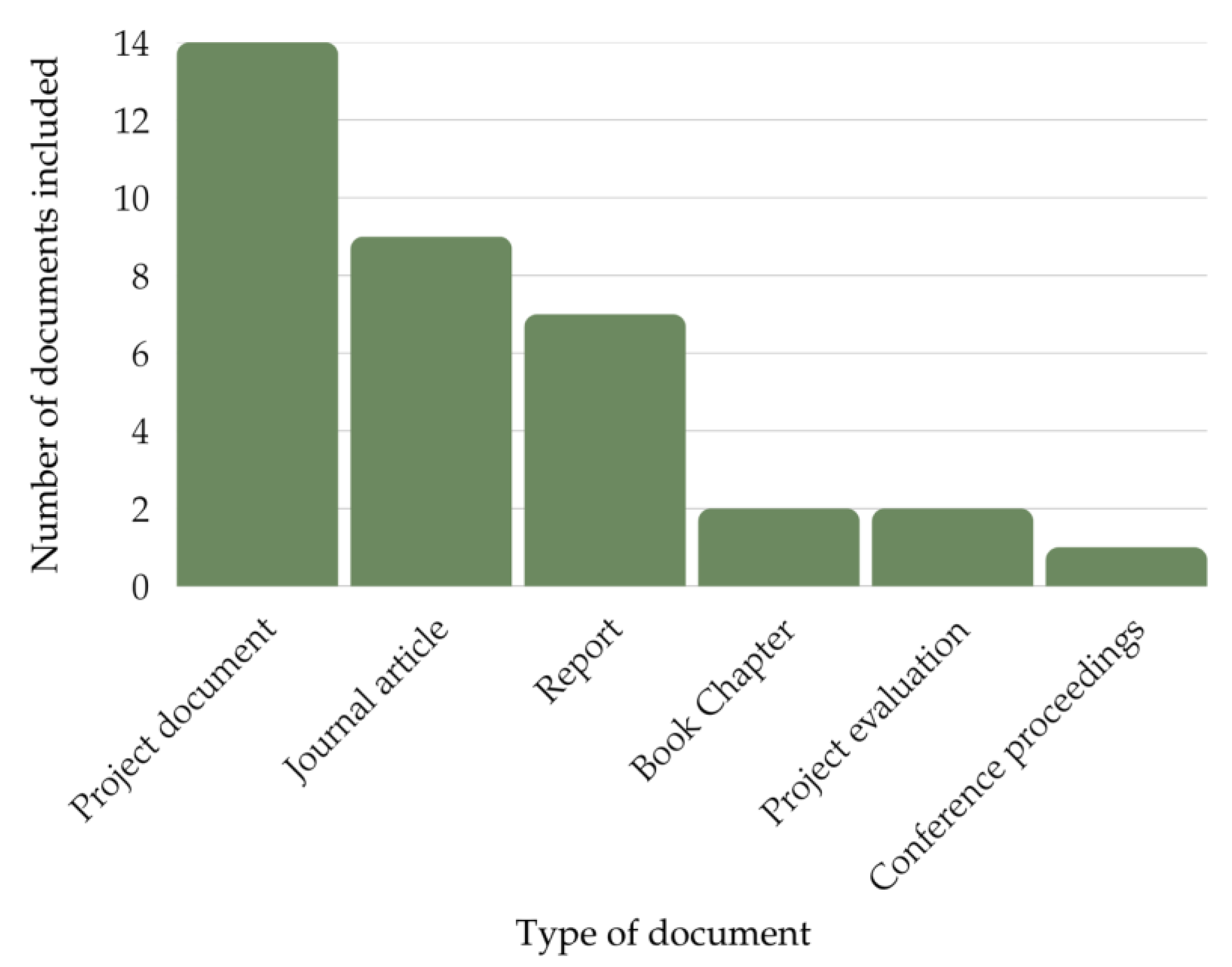

No area of evidence collected in this map can be said to be comprehensive or abundant, but the richest area of evidence identified in this map is the training programs carried out in Asia reporting economic outcomes for participants. The same issues outlined above may impact evidence synthesis in any area of the map since they persist across all countries, regions, and industries studied. However, our analysis highlights areas that could be elaborated upon for full systematic review, including interventions that incorporated training on some aspect of bamboo management, products, or marketing and took place in Asia, which represent the biggest cluster identified. Further primary research and a detailed case study are necessary to understand the evidence on the impact of bamboo industry development interventions in Africa and the Americas, which were underrepresented in the map. Most evidence (23 vs. 13 documents) was found outside of the peer-reviewed literature, indicating a research gap that could be addressed by academics.

As far as we are aware, the resulting systematic map database represents the first attempt to systematize evidence in this field. The database can be searched and filtered to see evidence on interventions carried out, including by filtering to a specific country, region, industry, date, or individual code. To allow agencies, governments, and others to fully understand the effects of livelihood development strategies that facilitate bamboo industry development, more comprehensive and holistic reporting of specific evidence, using rigorous study designs with clearly defined comparators such as baseline studies, is essential. Similarly, the development of systematic evidence map guidelines specifically for international development projects could open the door for more evidence synthesis of projects with mixed environmental and social outcomes, and varied evaluation methods and reporting.