1. Introduction

The significance of forests as a reservoir of many vital human benefits cannot be overstated. Throughout global history, forests have served as a source of energy, construction materials, and reserves of food. In recent decades, there has been a growing recognition, not only within the academic community but also among the broader public, of forests’ role in providing non-timber ecosystem services, primarily the regulation of the planet’s carbon balance and local microclimate on a global scale [

1,

2,

3].

However, humanity has significantly contributed to the degradation of the most valuable and directly accessible forests. Extensive deforestation in the Amazon Basin [

4,

5], large-scale logging in the world’s poorest countries [

6,

7], and the failure to systematically address the increase in the area and intensity of forest fires [

8,

9,

10] and forest pest outbreaks [

11,

12,

13] leading to forest decline in many regions of the world are the most important factors threatening the global forest ecosystem.

The quality of forest governance exerts a significant influence on the status and dynamics of forest resources. In this regard, national forest policies play a crucial role. The disparities in the efficacy of forestry organizations across diverse geographical regions are pronounced, ranging from the commendable standards observed in Northern Europe [

14,

15,

16] to the conspicuously deficient practices prevalent in Africa and South America [

17,

18,

19].

In the context of the world’s rapidly growing population, it is evident that the demand for forest ecosystem services will continue to increase. Consequently, issues such as the effective organization of restoration and the reproduction of forest resources will require increasing attention. The formation of effective forest policy at the national level is imperative to influence the quality of forest management.

Russia offers a noteworthy illustration of this phenomenon. Although the nation has the world’s largest forest reserves by area (809 million ha), it ranks far from the top in terms of forest utilization. In 2023, the country harvested only 188 million m

3 of timber, contributing only 0.8% of the GDP. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, there was a precipitous decline in logging activities. However, the country has since achieved a partial restoration of Soviet production levels, capitalizing on opportunities to augment exports to European and Southeast Asian countries, particularly China [

20,

21,

22,

23]. A more than 1.5-fold decrease in logging does not necessarily indicate an improvement in the quality and quantity of forest resources. The increasing frequency and intensity of wildfires [

8,

10,

24] and relatively low timber growth due to the cold climate, in conjunction with low rates of forest regeneration, lead to a reduction in the balance of net timber growth in the country. According to official calculations by Rosstat, the national statistical body, the country’s timber reserves have decreased by 0.4% over the past two years, equivalent to 312.5 million m

3. However, given the known limitations of official statistics on forests in Russia [

25,

26], the actual losses are likely to be even higher. In the event that logging recovers from the 2022–2023 sanctions restrictions [

22] and begins to grow, it is probable that the rate of deforestation will increase.

The implementation of public administration methodologies analogous to indicative planning approaches within the Russian context necessitates the establishment of development objectives with quantitative targets, not only on a national scale but also for specific sectors of the economy [

27]. In response to the challenges posed by the gradual degradation of forests, the Russian government has initiated a series of initiatives aimed at accelerating reforestation as part of the National Development Goals for the period of 2018–2024. Consequently, the reproduction of forest resources has become a priority for the entire state policy. A total of RUB 35 billion from the federal budget was allocated for the implementation of measures related to forest restoration within the FRP. Concurrently, the area of annual reforestation has increased by more than one and a half times. Nevertheless, this is insufficient to overcome the negative trends in the dynamics of Russian forests.

The evidence suggests that the objectives formally declared in order to improve forestry in Russia have thus far not been accomplished and that the objective of sustainable forest management has not been achieved. The objective of this article is to examine the rationality and coherence of Russia’s state forestry policy over the last two decades, with the aim of elucidating the underlying causes of the current situation and proposing potential solutions for its rectification.

In this paper, I test several hypotheses about the design and outcomes of the Federal ‘Forest Restoration Project’ (FRP), which is a part of the National ‘Ecology’ Project:

Hypothesis (H1). The FRP objectives were initially designed to be unambitious but easily achievable. Their fulfillment was supposed to contribute to the partial solution of certain problems in the Russian forestry sector.

Hypothesis (H2). The size and structure of the FRP’s financing was obviously insufficient for a significant transformation of the country’s forestry sector.

Hypothesis (H3). Although all FRP targets were met and reforestation rates in Russia increased significantly, the trend of increasing annual forest loss was not reversed.

Hypothesis (H4). Differences in the level of development between Russian regions, the role of forestry in their economies, and regional expenditures on forestry do not have a significant impact on the dynamics of forest loss.

The article is structured as follows:

Section 1 provides the rationale for the relevance of the problem of the influence of public policy on the state of forestry with a focus on the problems of Russia and formulates a statement of the research problem, as well as presenting hypotheses.

Section 2 examines successful practices for changing the approach to forest management in leading countries and also highlights the challenges in nations with high rates of forest loss.

Section 3 provides a detailed description of the data sources used and the content of the quantitative research methods, including descriptions of econometric modeling problems.

Section 4 outlines the main findings of the study. It is divided into

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3 and

Section 4.4, each of which describes the results of hypothesis testing for Hypotheses (H1)–(H4) and is named in the order of their succession.

Section 5 summarizes the findings of the study. In

Section 6, I speculate on the possibilities for the development of the study and the prospects for further development of national forest restoration initiatives.

2. Literature Review

The role of the state in overseeing the advancement of specific industries is frequently pivotal, as evidenced by numerous studies demonstrating that market interactions and private initiatives are predominantly influenced—either stimulated or impeded—by public policy [

28,

29,

30]. Government intervention manifests not only through alterations in the established rules or practices but also through direct investments or divestments in the development of specific sectors. Consequently, it is public policy that ultimately determines the long-term nature of economic development, even in cases where private capital plays a significant role.

The ownership of natural resources is frequently not private, where the state retains a substantial portion of the bundle of title to a deposit or parcel of land with minerals, water, or forests, thereby controlling the utilization of the natural asset. In the case of forests, this is almost always the case. Only rarely do governments give forest land to private owners under full, non-exclusive tenure without interfering at all in its management [

31,

32].

Nevertheless, numerous countries maintain substantial or nearly complete state ownership of their forestry resources. This model of forest management entails the allocation of rights to lease forest land or the right to purchase forest plantations to private individuals and companies by the state [

33]. Concurrently, the state may engage in some degree of logging activities. This diversity in ownership and management structures engenders significant research interest, particularly concerning its impact on forestry outcomes [

34]. The impact of public policies on forestry is a focal point of numerous studies worldwide [

35,

36].

A critical factor in the variation in forest development outcomes is the presence of differences in institutional, historical, and other country-specific business conditions. This phenomenon is evident in regions that exhibit similar geographical and environmental characteristics but are geopolitically divided across different countries [

37,

38]. The divergent regulations governing the utilization of natural resources give rise to markedly divergent standards of their utilization. The Amazon River Basin offers a compelling example that substantiates this theory. The deforestation rates in Peru and Brazil exhibit significant disparities, contingent on the institutional frameworks in place [

39]. Despite considerable initiatives by developed countries to invest in a program to combat deforestation in these regions, significant progress remains elusive [

4,

5,

39,

40]. Furthermore, there are reasonable doubts about the possibility of such progress in principle until these countries overcome the other significant macroeconomic challenges that accompany their development [

41].

The most significant institutional changes in Europe’s forestry sector pertained to the promotion of bioeconomy development, which was influenced by the heightened focus on addressing change challenges [

42,

43,

44,

45]. The policy of incentivizing forest bioeconomy has resulted in the substantial procurement of wood raw materials for bioenergy fuel production from the Baltic States and Russia, as well as the expansion of wood pellet and briquette production from forest industry waste [

46,

47].

The United States of America, a global leader in timber consumption, is a notable case study. It boasts a substantial timber market, driven by the demand for building materials and the production of board, pulp, and paper products for its wealthy population of over 300 million [

48]. Strategically located away from major timber markets, the United States relies on domestic timber resources and imports from Canada and South America. The market is balanced, and the country’s own timber resources are abundant enough that there are even occasional situations of domestic producer protectionism policies even vis-à-vis Canada, let alone China [

47,

48,

49].

In recent decades, the most notable changes in state forest policy have been observed in China, which has undergone a transformation into a major global manufacturing hub. This transition has resulted in an increased demand for raw materials, including timber [

50,

51]. However, the natural capacity of China’s forest ecosystems is not unlimited and, moreover, experienced large-scale deforestation in the mid-20th century. In the 2000s, China’s leadership recognized the need to address its reliance on foreign timber supplies, leading to a significant reduction in domestic logging and a push for afforestation initiatives [

52,

53]. The outcomes of these measures have included a notable deceleration in the rate of deforestation in recent decades [

51,

52].

The success of China’s economic reforms can be primarily attributed to a unique combination of decentralizing local governance and establishing ambitious development goals for monitoring [

54]. In contrast, Russia has not experienced the rapid degradation of its forest resources or the implementation of effective strategies to increase its forest area [

23,

35,

55,

56]. The nation’s forestry sector finds itself in a predicament characterized by a relatively modest domestic demand for forest products and a nascent global market that offers minimal incentives for substantial expansion in logging activities.

The forest ownership reforms initiated in the mid-2000s were actually curtailed, so currently, 100% of Russian forests are state-owned [

57,

58,

59]. Private businesses have the option to lease forest land plots for periods of up to 49 years, with the possibility of extending the contract or purchasing the right to harvest forest plantations and subsequently dispose of them at their discretion. It is evident that the prevailing legal framework for forests promotes a predatory approach to their management. Businesses demonstrate a limited interest in making long-term investments in the reproduction of forest resources; instead, they seek to lease additional plots at regular intervals, as forestry resources in the world’s largest country are believed to be inexhaustible [

20,

21].

Quantitative assessments of forestry efficiency in Russia are relatively rare. International research teams have historically prioritized Russia’s forests as a source of raw materials for the global economy or as a carbon asset [

60]. Conversely, the domestic Russian research agenda has centered on identifying and delineating the numerous challenges and limitations of the forestry sector, predominantly in a qualitative manner [

61]. A prevailing consensus among these studies is that significant improvements in the forestry sector and other sectors impacted by environmental issues in Russia are unlikely to occur without a comprehensive restructuring of environmental protection and restoration policies and practices throughout the country.

The results of the implementation of national projects in Russia are of interest to researchers in general, although it cannot be said that the literature on this subject is abundant [

27,

62,

63,

64,

65]. Polterovich has proposed the establishment of “catch-up” development institutions in Russia, which are defined as mechanisms that are not merely replicas of the most effective models but rather are designed to align with the unique characteristics of local cultures, thereby facilitating the realization of the nation’s advanced development objectives [

66,

67]. The utilization of these institutions is intended to mobilize the full spectrum of society’s available resources and social capital to address the most pressing issues that have accumulated over time. To operationalize this approach, a master development agency was proposed, endowed with a substantial budget and the authority to function beyond the conventional government framework. This approach exhibits certain characteristics of indicative planning methods, which have found practical applications in France and some other countries, though they have not yet become mainstream [

68].

3. Materials and Methods

In this paper, a range of prevalent data analysis techniques, including descriptive statistics, visualizations, and econometric modeling, is employed.

The primary data source for statistical analysis is Rosstat. Observations for subjects of the Russian Federation with almost no forests were immediately excluded from the regional dataset. Additionally, observations that exhibited unrecoverable data omissions were excluded from the analysis. Notably, no such omissions were identified in the federal-level data.

Furthermore, a methodology is developed for the purpose of comparing official state statistics with independent satellite data, which can be used to analyze actual forest losses. This approach is based on observations from the Global Forest Watch (GFW) project [

69]. I have previously applied the GFW data to analyze drivers of the spatial distribution of the forest carbon budget in Russia [

70].

The analysis of the structure of budget expenditures is based on data from the Federal Treasury of Russia regarding the federal budget. In this analysis, I consider the budget administered by the Federal Forestry Agency (Rosleskhoz), which is responsible for the organization of forest protection, restoration, and reproduction in Russia. The aggregation of figures for individual items and groups of budget expenditures and revenues is based on the author’s expertise.

The maximum available statistical observation period spanned 15 years from 2009 to 2023; however, in some cases, it was necessary to limit this period due to the shortage of some variables. Consequently, the regression calculations consider the period from 2013 to 2023. Special attention was paid to the time period from 2018 to 2024, when the implementation of the FRP was ongoing.

Descriptions of data variation over time, interregional differences, and other characteristics are provided in the relevant sections, graphs, and tables of the article below. Data processing, model calculations, and visualizations were performed in the R environment (v 4.4.2) with extension modules [

71,

72,

73,

74].

All values are given in Russian rubles (₽, RUB) at 2015 prices. The December-to-December consumer price indices for goods and services, as reported by the Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat), are utilized in the discounting calculations.

To analyze the impact of interregional differences in the costs of forestry measures, I use panel regression analysis methods. The baseline model is based on a standard pooled regression estimated using the ordinal least squares method (OLS). The following equation is estimated:

where

is the area of tree cover losses according to GFW data,

is the volume of logging,

is the area affected by fire, and

represents the regional expenditures (both sourced from budget and the forest industry).

is the intercept, and

is the error term.

are the regression coefficients. The index

stands for the identifying number of a region, and

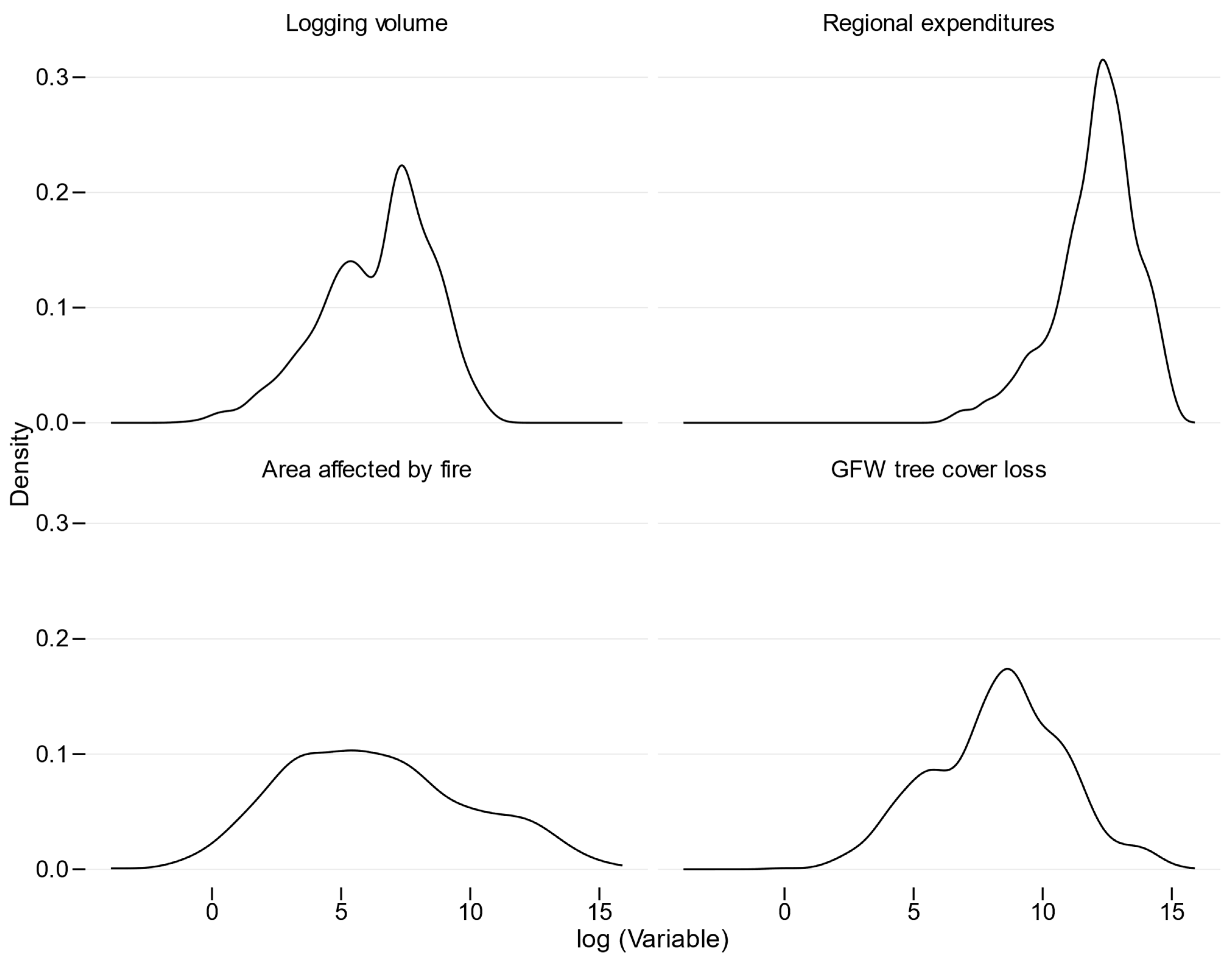

stands for the year. As the distributions of all variables are right skewed, the values of the variables are log-transformed (see

Figure A1 in

Appendix A).

The Chow test [

75] is a statistical procedure that enables the assessment of whether the fixed-effects model exhibits superiority over the pooled specification. In most cases, it is the fixed-effects specification that is used for panel regressions:

Here, captures unobserved heterogeneity between regions. The other elements of the regression remain the same.

Since endogeneity almost inevitably arises in such regression models, the instrumental variable method with the Balestra–Varadharajan–Krishnakumar transformation is used to control for it [

76]. The instrumental variable for logging volume is the forest cover of the region. The number of forest fires is the instrumental variable for forest fire area. The consolidated expenditure of regional budgets for all purposes is chosen as an instrumental variable for total regional expenditure on forestry. All variables satisfy the condition of high correlation with the corresponding exogenous regressors and do not affect the random error.

Other variants of panel regression models (e.g., with random effects) are not considered, as the study design implies the use of a constant set of Russian regions.

Regressions on regional data are also employed to adjust Rosstat data concerning forest fire areas. The technique for this calculation is delineated in

Section 4.3.

The article cites the original official state documents in Russian, translated into English by the author. Consequently, the author assumes full responsibility for the accuracy and thoroughness of the translation.

4. Results

4.1. Russian National Development Goals for Forestry: Quo Vadis?

The genesis of the contemporary Russian institution of National Development Goals projects can be traced back to 2005, when four principal national projects designed to “enhance human capital” within the country were endorsed. Three projects (‘Education’, ‘Health’, and ‘Affordable and Comfortable Housing for Russian Citizens’) were specifically focused on the development of the social sphere. Another project subsequently evolved into a sectoral project: ‘Development of the Agro-Industrial Complex’. The program was initially designed for the period of 2006–2018; however, it was subsequently terminated ahead of schedule in 2012.

The formal conclusion of the program of priority national project did not signify the termination of the initiative but rather a transformation of its conceptual framework. In May 2012, a novel approach to addressing this issue was initiated: At the inception of each new presidential term, a new set of documents is executed delineating the directives for the Russian government to attain the national development objectives of the country over a six-year cycle (the duration of the full presidential term).

In the subsequent cycle of approval of the National Development Goals, the format of state projects was reintroduced to finance and monitor their achievement. A total of 14 national projects were designated, each comprising a dozen additional federal projects. Further, at the level of federation subjects (i.e., the Russian administrative units of the second level), each federal project began to correspond to its regional counterpart.

The concept of national projects is to distinguish current activities and initiatives that are specifically oriented toward the advanced development of individual industries. Financial resources are allocated independently in order to achieve the nation’s established development goals, which are positioned as the most important priority and a source of self-replicating growth in the future.

A synopsis of the three cycles of establishing Russia’s National Development Goals is provided in

Table 1.

The logic of National Development Goals entails the establishment of specific quantitative benchmarks that characterize the state of certain spheres of social life and the economy. Such benchmarks may include the average wages of education and healthcare workers, the number of high-paying jobs created, and so on. The achievement of target benchmarks is recognized as the primary task of a national project and a measure of its success.

However, some targets are formulated in a qualitative rather than quantitative form. Such qualitative targets are often vague and open to interpretation, making it difficult to assess both the current state of affairs and the evaluation of progress in addressing the problem. This was exemplified by the forestry goals presented in

Table 1. In both the 2018–2024 and 2024–2030 cycles, the objectives are broad and abstract, such as “forest restoration” (in the first case, the specification was added: “...including on the principle of their reproduction in all areas of felled and dead forest stands”).

The concretization of actions within the framework of national projects is further specified in passports, where specific target indicators, deadlines for their achievement, and responsible persons, as well as the amount of funding and its sources, are highlighted. It was initially assumed that the national projects were named so for a reason: they should not be only federal state budget projects. A certain share of financial and organizational participation in these projects should be borne by the authorities of Russian regions, as well as by businesses.

Specifically, within the framework of the federal Forest Restoration Project of the National ‘Ecology’ Project, the following target indicators were defined in the development of project passports in 2018 (see

Table 2). The initial version of the passport delineated only two objectives: (a) to achieve parity between the volume of reforestation and afforestation and the volume of felled and burned forest plantations, and (b) to reduce “damage from forest fires” by nearly threefold by the conclusion of the project implementation (in current-year prices). Following a series of modifications to the document, which exhibited consistent resistance throughout its existence, two additional indicators were incorporated: preservation of (c) the forest cover of the country’s territory and (d) the amount of carbon sequestration by forests.

The achievement of these values was envisioned through a set of outcomes (see

Table 3). The proposed outcomes included the modernization of the fleet of specialized ground equipment used by state institutions for reforestation, afforestation, and the protection of forests from fires. Furthermore, it was anticipated that the initiative would facilitate the establishment of a seed fund for reforestation initiatives and the modernization of information systems regarding available lands for reforestation. The main indicators included the target volumes of reforestation, which were set at 1200 thousand ha by 2021–2022 and 1554 thousand ha by 2024.

The sequence of financing and the values of the indicators suggested that the fulfillment of the established objectives would be distributed over time for the entire duration of the national project.

The set of targets and results presented was initially met with criticism [

77]. First, while the updating of equipment itself is certainly a necessary measure, in isolation from other measures, it is unlikely to have an impact on the top-level objective (forest restoration). For example, the targets do not include the costs of increasing the salaries of forestry workers, who have been chronically underfunded for decades. Second, increasing the volume of forest planting does not in itself guarantee the quality of these works. The survival rate of seedlings is never 100%, and thus restoration based on the standard 1:1 will not even be able to ensure the simple reproduction of forest resources. Third, the fire damage estimates calculated according to the state methodology are abstract values that clearly underestimate the total losses of forests. Fourth, maintaining the volume of carbon absorption by forests at the current level is unlikely to be directly related to the goals set in the national project. Addressing low-carbon development in an integrated manner and through other government initiatives is imperative [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82].

Therefore, an analysis of the composition of the national project’s activities reveals an impression of incompleteness, as it addresses a significantly narrower task than is outlined in the National Development Goals. In the subsequent section, this assumption will be substantiated and elucidated.

4.2. Money for a Breakthrough in Reforestation and Forest Fire Protection

The system of forest relations in the Russian Federation is organized in such a way that forestry is a chronically deficit budget item. Its revenues are provided by payments for the lease of forest areas or the purchase of forest plantations, with the largest part of the revenue allocated to the federal budget and the remainder allocated to regional budgets according to the location of logging activities. The total royalties collected are insufficient to fully offset the government’s minimal expenditures on forest management, underscoring a persistent budget deficit. For instance, in 2021, the federal budget received RUB 44.6 billion in forest use fees, whereas the net profit of the 10 largest timber industry groups in Russia amounted to nearly RUB 140 billion. The federal budget’s expenditure for the same year amounted to RUB 50.6 billion. In certain years, particularly when substantial expenditures were necessary to confront forest fires, the deficit of the forest part of the federal budget reached 54.4% (see

Figure 1).

The government’s reluctance to allocate additional funding to forestry initiatives is not unexpected, given its perception of the sector as unprofitable. Concurrently, there is a notable reluctance to substantially increase payments for the utilization of forest resources. Such an increase would enable the withdrawal of a more substantial portion of rent to the budget, thereby facilitating the financial support of restoration and reproduction efforts within the forestry sector.

A critical evaluation of the FRP reveals that it was incapable of providing a substantial financial stimulus to the advancement of the forest management sector. The total budget for the implementation of all project activities was initially set at RUB 151 billion. However, only RUB 40.6 billion of this budget was to be provided by the federal government, with the remaining RUB 4 billion sourced from regional authorities and RUB 106.5 billion raised from “extra-budgetary sources”, i.e., forest businesses. The introduction of the so-called “compensatory reforestation” rules served as the mechanism for such fundraising. Under these rules, forest users were obligated to plant forests at their own expense at the rate of one tree planted for one tree cut down.

While these amounts appear substantial, when converted to an annual scale and adjusted to constant 2015 prices, the national project expenditures in 2023 represented a mere 3.7% of the gross expenditures of all sources on forestry (including business funds), or 7.3% of the current regular federal budget expenditures. Thus, the funds of the national project can be perceived only as some addition to the deficit budget of the forestry sector. As demonstrated above, there is ample evidence to support the hypothesis concerning the inadequacies of the project’s measures and objectives. Utilizing an additional funding source, Rosleskhoz effectively addressed a long-standing issue, namely, the scarcity of modern forestry equipment, as well as the moral and technical obsolescence of existing equipment. The replenishment of seeds and the stimulation of the forest planting material cultivation sector are additional achievements. However, it is evident that the available financial resources were insufficient to achieve more ambitious goals. The rationale behind the decision to not allocate project funds to augment foresters’ salaries is also evident. The project’s implementation timeline necessitated the maintenance of salary levels, which could not have been assured within the existing budgetary constraints of the authority.

Thus, the reasoning behind the development of formal project indicators can be readily understood. If these indicators were to encompass more precise content and an ambitious scope, their realization would prove to be impracticable. This, in turn, would invariably pose a threat to the official, who would face the prospect of prosecution and, consequently, would seek to circumvent such a scenario.

4.3. Progress Toward Achieving the Stated Goals

The formal objectives of the national project were not only met but partly substantially exceeded. The level of forest cover remained unchanged (46.4%). The ratio of the area of reforestation and afforestation to the area of felled and dead forest plantations in 2024 exceeded 135.1%, far surpassing the targeted value of 100% (see

Table 4). The area of reforestation remained at a constant level of about 850–950 thousand ha each year during the 2010s. After the implementation of the national project, the indicator was increased by more than three-quarters, to almost 1.5 million ha. Concurrently, reforestation efforts are being implemented on a negligible scale, amounting to approximately 10 thousand ha.

Conversely, the calculated damage to forest plantations from forest fires exceeded the plan and was more than twice as high as the projected amount. In 2024, the estimated damage amounted to RUB 5.8 billion, significantly exceeding the estimated RUB 12.5 billion outlined in the national project passport as of 2018.

According to the most recent National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report, which clarifies the approaches to estimating the absorption capacity of forests, the value will increase by 34%, thus exceeding the expectations of the corresponding indicator of the national project [

83,

84].

In the language of official reporting, the project can be recognized as having been successfully implemented. However, the question remains as to whether the sectoral national goal was achieved with its help. It should be recalled that it was formulated as “forest restoration”. In defining quantitative indicators to assess the attainment of this objective, the primary focus was on the intensification of reforestation efforts in Russia. The objective was to achieve equilibrium between the areas of annual deforestation and their restoration through reforestation and afforestation. The second component of the target setting was related to wildfire management.

Until 2020, official government data regarding the area of forest loss was not published; instead, the structure of forest losses by source was disclosed on an annual basis. Beginning in 2020, however, Rosstat has published the total area of forest loss by source. The values of the indicators are surprisingly small; for example, in 2022, according to these data, only 188.2 thousand ha were lost (see

Table 4). A comparison of these figures with those from alternative sources indicates that the former significantly underestimate the scale of actual forest loss in Russia.

However, the assessment of equilibrium between forest restoration and related economic factors presents a considerable challenge. Relevant statistics have only been published by Rosstat since 2022 within the framework of natural resource satellite accounts of national accounting. According to these short time series, there was a decrease in forest area of 0.4% from 2021 to 2023. To conduct more accurate assessments of forest loss, it is necessary to construct a longer series of observations using alternative sources.

While observation series on the area of forest fires are available, they account for the area affected by fire rather than losses, leaving the lethality of such fires remains unknown. Since the implementation of the FRP, data on economic damage from forest fires have been published, which are calculated according to a specially developed methodology. The estimates obtained in this way do not directly indicate the volumetric and qualitative characteristics of timber losses. Consequently, the sole adequate state indicator for these purposes is the area of forests affected by fires.

The area of land where timber harvesting took place is not disclosed in the statistics. Judging by the known volumes of logging and timber reserves per hectare, annual losses of forest areas in Russia range from 1 million to 1.5 million ha.

Other sources of forest disturbances insignificantly influence the total area of forest losses in Russia. The main such factor is forest damage caused by outbreaks of mass reproduction of insect pests [

85,

86,

87]. In only a subset of these cases does the action of phytophages lead to stand collapse; more frequently, the trees are weakened, which eventually makes them excellent fuel for fire in the subsequent season. In such cases, the direct cause of forest death will be the fire and not the action of forest phytophages that contributed to the event.

The Global Forest Watch project provides data that can be used to supplement official statistics and cross-check them. A distinguishing feature of these data is their comprehensive coverage of total forest losses from diverse sources, including logging, fires, and other disturbances. Consequently, direct comparisons between these data and those reported by the Rosstat are not feasible. Nevertheless, this does not preclude the possibility of making indirect comparisons.

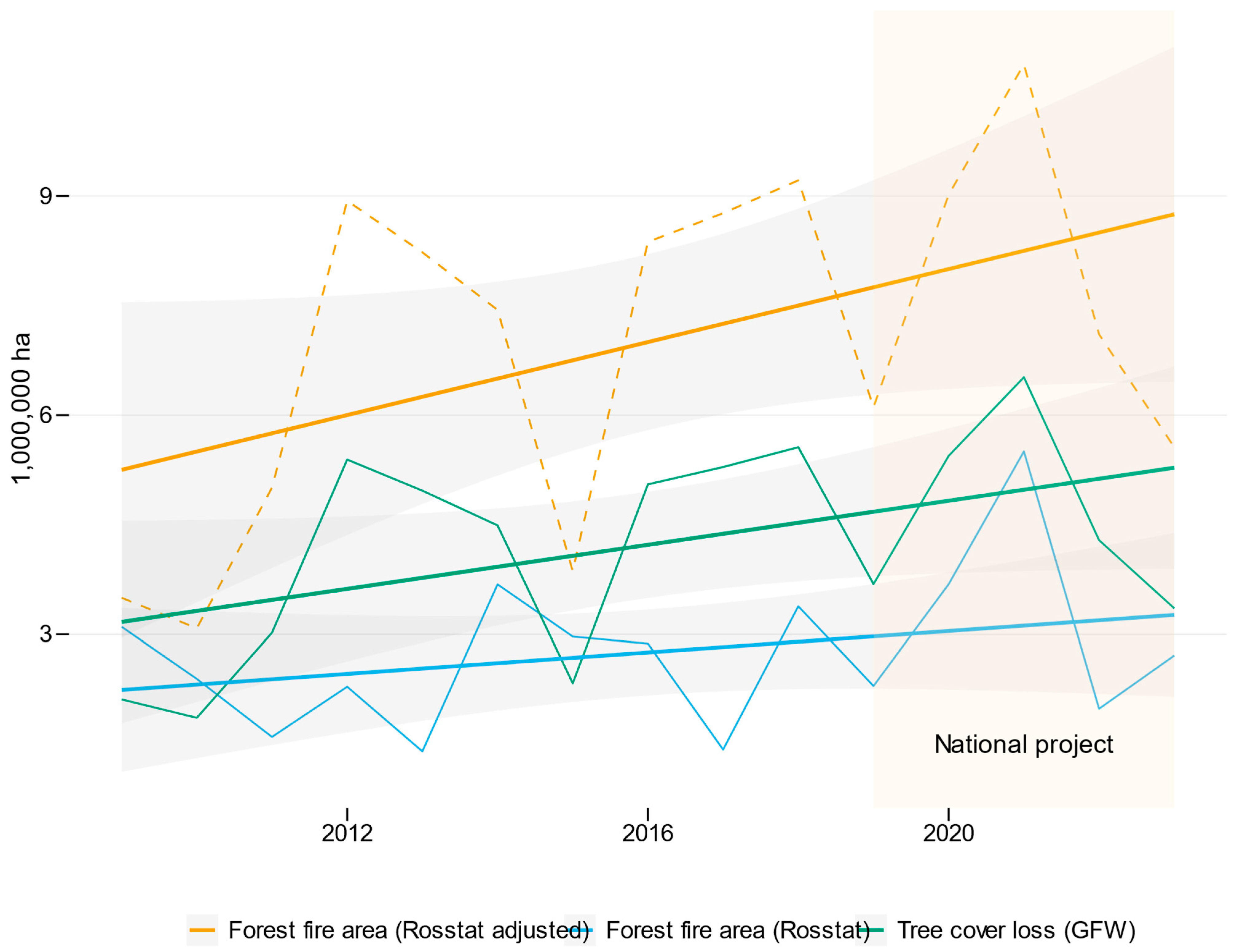

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the correlation between Rosstat data and tree cover losses according to GFW data is not high. The analysis reveals an absence of years in which the dynamics of indicators align, and in some cases, the data are distinctly inconsistent.

It is hypothesized that satellite monitoring data and the calculations of the Global Forest Watch project, based on these data, are the most reliable and independent sources of data on forest loss worldwide. Therefore, observed discrepancies with national data should not be interpreted in favor of the latter. The reasons for these discrepancies appear to be differences in methodologies and observational goals, as well as changes over time. It was previously noted that Rosstat provides data on the area affected by fire but does not disclose the lethality of these events.

In the process of examining the data, a methodology was discovered for adjusting the Rosstat indicator to align with the trends observed in the GFW data. It was found that by subtracting the area of fires that were not extinguished (a new indicator observed since 2017) from the area of forests affected by fire, the resulting series exhibits a strong correlation with the dynamics of the GFW indicator. The period of missing data between 2013 and 2017 can be imputed using a simple regression equation derived from regional data:

The series obtained in this manner (shown as a yellow dotted line in

Figure 2) facilitates the estimation of the contribution of the fire factor to forest loss in Russia. The ongoing decline in Russian forests is attributable to an increase in the area of fires and their lethality. Contrary to this, there is no evidence to suggest that the FRP has had any influence on this growth, as the trend is stable, and the indicator itself is subject to the natural cyclicity of forest burning.

4.4. Regional Contributions to Forest Restoration: A Panel Regression Exercise

Russia is a vast nation with notable variations in forestry conditions, the role and importance of the sector in regional economies, and the state of forestry management at the federal level. Despite the high degree of centralization of state management in the country, the regions exhibit variability in the quality and completeness of implementation of any central initiatives. These considerations, in conjunction with the limited availability of regional data concerning the dynamics of forest resources within the Russian Federation, necessitate the implementation of a statistical experiment.

The implementation of national projects entailed the involvement and co-financing of their activities by regional authorities and extrabudgetary sources. The Federal Forestry Agency’s territorial bodies were entrusted with the responsibility of supplementing federal expenditures for the procurement of equipment essential for reforestation and the protection of forests from fires, utilizing a portion of the funds allocated to regional budgets for forest use. Consequently, the forestry sector was obligated to allocate resources to reforestation and afforestation, thereby compensating for the previously mentioned timber cuts. The volume of these “regional investments” can be calculated using data from Rosstat’s public statistics.

A comparison of the figures on the dynamics of forest losses, logging volumes, and areas of forest fires with the figures on the regional forestry budgets can reveal whether differences in the volumes of regional forestry budgets have manifested themselves in the results of “forest restoration”.

The main parameters of the dataset used are described by the following descriptive statistics (see

Table 5). All panels used are balanced, i.e., they do not contain omissions of values. Data are observed for 76 regions of Russia and 11 consecutive years from 2013 to 2023. The distributions of the logarithms of the variables directly included in the regression models are depicted as kernel density curves in

Figure A1 of

Appendix A.

The specifications of the regression models for panel data are outlined in

Section 3. First, model M1 is estimated using OLS with no additional features according to Equation (1). Then, model M2 is estimated in the fixed-effects (FE) specification of Equation (2). A similar pair of models is then estimated for the variant with instrumental variables (models M3 and M4, respectively). In the case of the default specification of the equations, the F-statistic of the Chow test is 17.63 (

p < 2.2 × 10

−16), indicating that the fixed-effects regression is preferred. A similar result is obtained for the instrumental variable specification, where the F-statistic is 12.659 (

p < 2.2 × 10

−16).

The estimates of the regression models are summarized in

Table 6.

Although the OLS models (M1 and M3) show a very good fit, high values for the coefficients of determination (0.696 and 0.679, respectively), convincing significance of the parameter estimates for logging volumes and areas affected by fire, and reasonable values for the coefficients themselves, these models cannot be directly applied to the analysis. The Chow test and the following considerations indicate that FE models should be used in this case. Russian regions are too different from each other in all parameters to exclude the influence of heterogeneity, which the FE specification captures well.

At the same time, models M2 and M4 show an extremely poor fit and do not yield significant coefficients. In addition, the instability of the values of the model parameters (e.g., the coefficient of the logarithm of logging is significant and for model M2 is 0.235, while for model M4, it is −1.179) indicates that regional variations in logging volumes, fire intensity, and investments in forestry do not actually affect differences in forest loss. It is important to note that the coefficient of regional forest investment is not significant in any of the specifications considered.

It can be stated that there is no convincing evidence to support that regional authorities and businesses were able to be more or less efficient in spending on reforestation or forest fire control. They acted in strict accordance with the equalization policy set by the federal decision-maker. Thus, it is impossible to identify either positive or negative regional practices.

5. Discussion

The results of the study allow for the formulation of several conclusions regarding the effectiveness and efficiency of the FRP in achieving the national strategic goal of forest restoration.

First, over the course of the last decade, the Russian government has officially acknowledged the problem of the gradual reduction in national forests. When formulating the country’s development goals in 2018, the problem of forest restoration was recognized as an important state priority and became a component of the FRP.

Second, while the allocation of funds for the national project was substantial, it was also clearly insufficient to exert a change in the situation in the industry. However, the funds did enable the renewal and replenishment of the outdated fleet of specialized equipment utilized for reforestation and forest fire protection. However, the allocated funds, amounting to less than 10% of the annual regular budget of the Russian forestry sector, were evidently inadequate for addressing the comprehensive challenges confronting the forestry sector, which have been accumulating for three decades since the dissolution of the USSR.

Third, due to the aforementioned reasons, the designers of the national project considered the impossibility of achieving ambitious goals and formulated the formal indicators of the program in such a way that they could be fulfilled in any case. The established indicative goals of the national project were found to be considerably less ambitious than those of “forest restoration”. This strategy enabled officials to circumvent potential penalties for noncompliance with the national project’s objectives.

Fourth, despite the formal fulfillment and even overfulfillment of the goals of the FRP, it is not possible to state that the problem of forest restoration has been solved. Notably, the country has witnessed a substantial surge in reforestation and afforestation efforts, with the volume of these activities increasing by more than one and a half times. The officially calculated “damage from forest fires” has been reduced. However, these outcomes have not been sufficient to halt the escalating rate of forest loss, a phenomenon that is substantiated not only by independent satellite data but also by the recently implemented indicator of the national accounting system in the domain of natural resources.

Fifth, despite the vast expanse of Russia and its forests, the outcomes of the FRP are evident throughout the country, exhibiting minimal disparities. Consequently, regions with substantial forest reserves and considerable investments in forestry do not exhibit markedly higher or significantly lower efficiency in utilizing these resources.

A notable supplementary outcome of the study is the derivation of numerous narrow conclusions regarding the quality and peculiarities of Russia’s publicly accessible state forestry statistics.

6. Conclusions

This article contributes to the literature on the analysis of the causes of forest loss in selected countries of the world using Russia as an example. It is shown that despite the fact that over the last 6 years, the Russian government has tried to significantly increase the rate of forest restoration by increasing the norm of compensation for felled forest plantations, it still has not been possible to reverse the trend of increasing net forest loss.

At the inception of the national project, I analyzed its passport in detail and came to the conclusion that the initiatives would not result in substantial alterations within the Russian forestry sector [

77]. The findings of this study, based on information available on the eve of the project’s completion, demonstrate the validity of the previously established conclusions. Initially unambitious goals have been adjusted downward over the years in favor of improved feasibility. The already limited financial resources were subjected to further cuts. Consequently, the project became a relatively minor addition to the budget of the Russian state forestry sector, enabling the upgrading of reforestation and firefighting equipment.

It would be imprudent to conclude that these endeavors were in vain. The rate of forest reproduction in the country has exhibited a marked increase. The material and instrumental base for the protection of forests from fires has been renewed. Nevertheless, these measures have not been sufficient to reverse the trend of the gradual reduction in Russian forests.

While deforestation rates may appear negligible at present, it is crucial to recognize the fundamental fallacy in assuming that the substantial national forest reserves, coupled with the relatively modest utilization rate, will ensure sufficient resources for both the present and future generations. This perspective is fundamentally misguided, as forests possess a high degree of multifunctionality, precluding their consideration as a singular source of raw materials for wood products. The annual loss of millions of ha of forestland represents a threat not only to national interests but also to the well-being of humanity.

Sooner or later, the problem will have to be fixed, and the longer the wait, the higher the cost. Nonetheless, the recently established national objectives for the period up to 2030 continue to exhibit the inertia of the preceding cycle, with no imminent breakthroughs anticipated.

The useful contribution of this paper is not only the detailed treatment of a specific sectoral problem but also the development of an approach for analyzing similar problems in other sectors covered by Russia’s National Development Goals. The present paper therefore offers an invitation to build on its findings and generalize them further.