Measurement and Validation of Market Power in China’s Log Import Trade—Empirical Analysis Based on PTM Model and AIDS Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Analysis

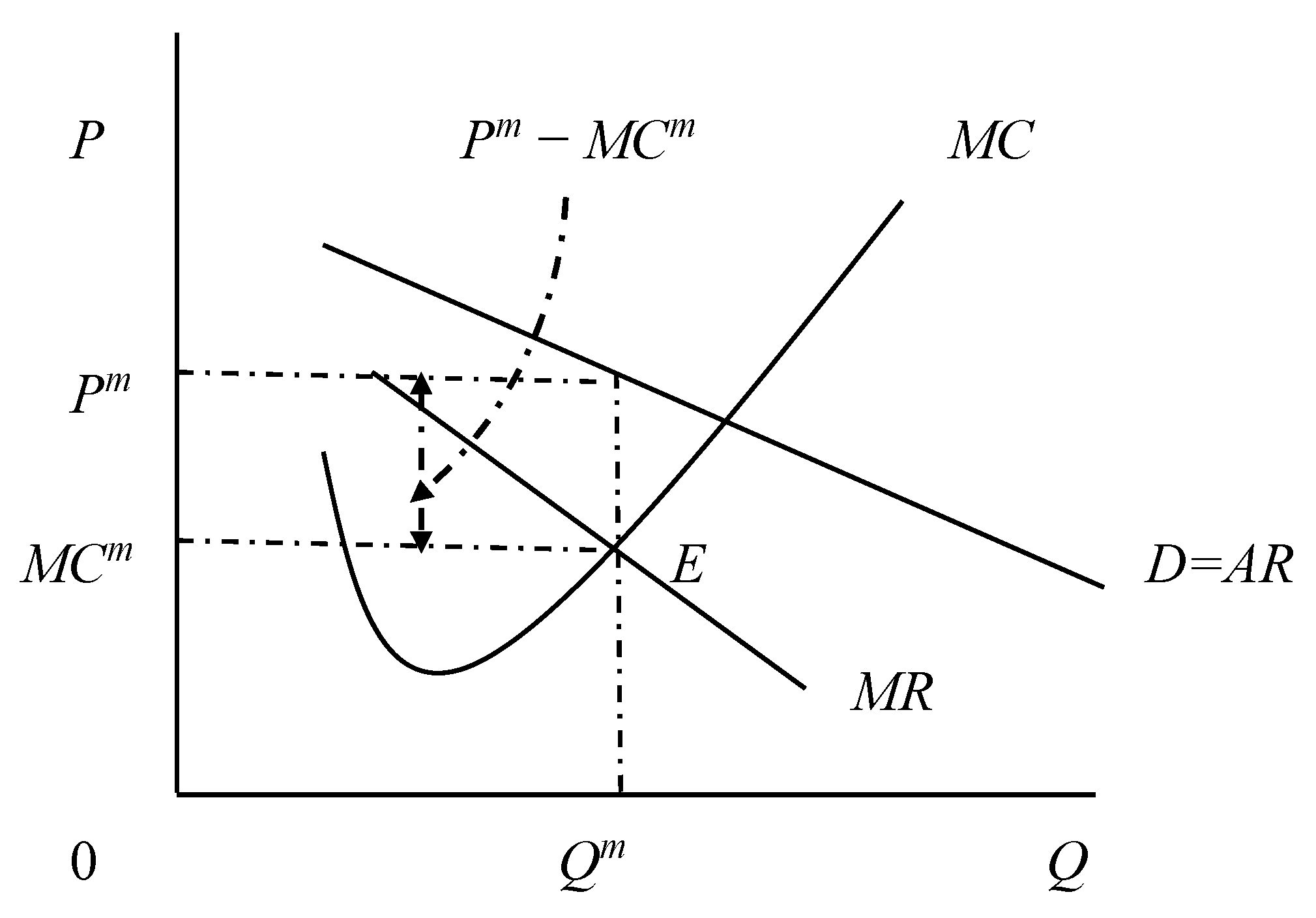

2.1.1. Whether Market Power Exists

2.1.2. Market Behavior Characteristics of Import Source Countries

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. PTM Model

2.3.2. AIDS Model

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Market Power Measurement

3.1.1. Diagnostic Tests for the PTM Model

- (1)

- Stationarity Test:

- (2)

- Cointegration Test

- (3)

- Hausman Test

- (4)

- Double Fixed Effects Test

- (5)

- Varying Coefficient Model Test

- (6)

- Wald Heteroscedasticity Test

- (7)

- Wooldridge Autocorrelation Test

- (8)

- Multicollinearity Test

3.1.2. Analysis of PTM Model Empirical Results

- (1)

- Category 1: China Holds Superlative Market Power

- (2)

- Category 2: China Holds Strong Market Power

- (3)

- Category 3: China Holds Weak Market Power

- (4)

- Fourth Category: China Holds No Market Power

3.2. Analysis of Market Behavior Characteristics of Source Countries

3.2.1. Analysis of Expenditure Elasticity

3.2.2. Simple Price Elasticity

3.2.3. Cross-Price Elasticity

4. Discussion

4.1. Enhancing Import Market Power

4.2. Diversified Import Strategy

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- China’s main trading partners can be categorized into four groups according to their market power in the log import trade. First, China holds superlative market power in log imports from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Myanmar. When the currency of these three countries appreciates by 1%, the timber prices in their currencies decline by 2.94%, 2.40%, and 1.20%, respectively, which is greater than the currency appreciation. Timber prices in RMB decrease by 1.94%, 1.40%, and 0.20%, respectively. Second, China holds strong market power in log imports from Russia, the DRC, and Mozambique. When the currency of these countries appreciates by 1%, timber prices in their currencies decrease by 0.95%, 0.88%, and 0.57%, respectively, which is greater than half of the currency appreciation. Conversely, timber prices in RMB increase by 0.05%, 0.12%, and 0.43%, respectively. Third, China holds weak market power in log imports from Papua New Guinea, Equatorial Guinea, France, Germany, Australia, and New Zealand. When the currencies of these countries appreciate by 1%, the log prices in their currencies decrease by 0.43%, 0.19%, 0.18%, 0.08%, 0.07%, and 0.01%, respectively, all less than half of the currency appreciation rate. In RMB terms, the log prices increase by 0.57%, 0.81%, 0.82%, 0.92%, 0.93%, and 0.99%, respectively. Finally, China holds no market power in Japan, Cameroon, and the United States. When the currencies of these countries appreciate by 1%, the price of logs expressed in their currencies increases by 0.19%, 0.47%, and 3.14% respectively, and the price in RMB increases by 1.19%, 1.47%, and 4.14% respectively.

- (2)

- As China increases its log import expenditure, it tends to purchase higher-quality and more valuable timber, while also placing greater emphasis on market transaction legality. Consequently, China is anticipated to augment its imports from source countries with no or weak market power. As illustrated in Table 5, with the exception of Indonesia, which has an expenditure elasticity of −0.92, all import source countries exhibit positive expenditure elasticities. Furthermore, China’s expenditure elasticities surpass 1 in several countries, including France (1.85), Japan (1.85), Laos (1.65), Germany (1.58), the United States (1.55), Australia (1.47), New Zealand (1.46), Canada (1.46), Cameroon (1.21), Equatorial Guinea (1.19), Papua New Guinea (1.14), the Solomon Islands (1.09), and Gabon (1.03), indicating a high degree of elasticity.

- (3)

- The simple price elasticity of logs from all source countries is negative. Specifically, the simple price elasticities for logs imported by China from Japan (−0.87), Equatorial Guinea (−0.79), Australia (−0.73), Germany (−0.67), Cameroon (−0.67), Papua New Guinea (−0.56), New Zealand (−0.44), Laos (−0.42), France (−0.38), Canada (−0.29), the Solomon Islands (−0.26), the United States (−0.23), and Gabon (−0.19) all have absolute values less than 1. In contrast, the simple price elasticities for logs imported by China from Mozambique (−2.07), Malaysia (−1.67), Russia (−1.47), the DRC (−1.37), Myanmar (−1.25), and Indonesia (−1.24) all have absolute values greater than 1. Countries with stronger market power can achieve higher total revenues by raising prices, whereas countries with weaker market power are more inclined to achieve higher total revenues by lowering prices.

- (4)

- Logs from different source countries are complementary in the Chinese market, indicating that China’s substantial log demand relies on simultaneous supplies from multiple countries and various types of timber. Specifically, the overall cross-price elasticities for New Zealand (−6.49), the United States (−1.98), Australia (−1.88), the Solomon Islands (−1.74), Papua New Guinea (−1.47), Germany (−1.06), France (−1.03), Laos (−0.64), Cameroon (−0.46), Canada (−0.25), Equatorial Guinea (−0.19), Gabon (−0.09), and Japan (−0.06) in the Chinese market are less than 0. Based on these findings, this study provides targeted recommendations for enhancing international market power and reducing trade losses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, L.; Pei, T.W.; Tian, Y. Trade creation or diversion?—Evidence from China’s forest wood product trade. Forests 2024, 15, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UN Comtrade Database. 2024. Available online: https://comtradeplus.un.org (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Utton, M.A.; Morgan, A.D. Concentration and Foreign Trade; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, J.S. Relation of profit rate to industry concentration: American manufacturing, 1936–1940. Q. J. Econ. 1951, 65, 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsetz, H. Industry structure, market rivalry, and public policy. J. Law Econ. 1973, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.N.; Hannan, T.H. The efficiency cost of market power in the banking industry: A test of the “Quiet Life” and related hypotheses. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1998, 80, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loecker, J.D. Recovering markups from production data. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2011, 29, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, P.K.; Knetter, M.M. Measuring the intensity of competition in export markets. J. Int. Econ. 1999, 47, 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C. Equivalence results for optimal pass-through, optimal indexing to exchange rates, and optimal choice of currency for export pricing. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2006, 4, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellerstein, R. Who bears the cost of a change in the exchange rate? Pass-through accounting for the case of beer. J. Int. Econ. 2008, 76, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T. Estimating time variation of market power: Case of U.S. soybean exports. Agric. Appl. Econ. Assoc. 2012, 8, 124775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.H.; Marchant, M.A.; Reed, M.; Xu, S. Competitive analysis and market power of China’s soybean import market. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2009, 12, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaura, K. Market power of the Japanese non-GM soybean import market: The U.S. exporters vs. Japanese importers. Asian J. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2011, 1, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.H.; Ye, L.X.; Wang, L. Changes of China’s soybean import market power and influencing factors. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 30, 2619–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P. Pricing to Market When the Exchange Rate Changes; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizgah, M.R.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Mosavi, S.H. The ability of Iranian exporters to price discriminate in agricultural sector trade: Case comparison of fig and grape. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 1411–1422. Available online: https://civilica.com/doc/1817140 (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Kim, S.H.; Moon, S. A risk map of markups: Why we observe mixed behaviors of markups. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2017, 26, 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, G.; Crowley, M.; Han, L. Invoicing and the dynamics of pricing-to-market: Evidence from UK export prices around the Brexit referendum. J. Int. Econ. 2022, 135, 103570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.H.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, H.W.; Huang, J.B. International market power analysis of China’s tungsten export market from the perspective of tungsten export policies. Resour. Policy 2019, 61, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.X.; Liang, Y.W.; Ru, Z.; Guo, H.J.; Zhao, B.J. World forage import market: Competitive structure and market forces. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, D.; Haller, S. Pricing-to-market: Evidence from plant-level prices. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2014, 81, 761–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Luo, W.J.; Xiang, X.Y. Exchange rate pass-through to export prices in China: Does product quality matter? Appl. Econ. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.W.; Feng, Y.C.; Wang, X.Q.; Yuan, G. Does higher market power necessarily reduce efficiency? Evidence from Chinese rice processing enterprises. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Yu, X.H. Estimating market power for the Chinese fluid milk market with imported products. Agribusiness 2022, 38, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Pan, Z. Responding to import surges: Price transmission from international to local soybean markets. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 82, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.L.; Xue, Y.J.; Quan, C.N.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.N. Oligopoly in grain production and consumption: An empirical study on soybean international trade in China. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2142818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.H.; Zheng, W.H.; Zhang, H.W.; Guo, Y.Q. Time-varying international market power for the Chinese iron ore markets. Resour. Policy 2019, 64, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marz, W.; Pfeiffer, J. Fossil resource market power and capital markets. Energy Econ. 2023, 117, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Lv, X.; Li, X.S.; Zhong, H.; Feng, J. Market power evaluation in the electricity market based on the weighted maintenance object. Energy 2023, 284, 129294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.Y.; Yang, Y.Y.; Jing, Z.X. Impact of long-term transactions on strategic bidding in the electricity market. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 2090–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.S.; Huang, T.; Bompard, E.; Wang, B.B.; Zheng, Y.X. Ex-ante market power evaluation and mitigation in day-ahead electricity market considering market maturity levels. Energy 2023, 278, 127777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.S.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L.P.; Wang, L.J. Measuring the market power of China’s medical product exports. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 875104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.W.; Li, X.; Cai, H.L. Market power, scale economy and productivity: The case of China’s food and tobacco industry. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.L. Demand elasticity of import nuts in Korea. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A. An almost ideal supply system estimate of US energy substitution. Energy Econ. 2013, 40, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, O.A. Income and Price Effect on Bilateral Trade and Consumption through Expenditure Channel: A Case of Chickp; North Dakota State University: Fargo, ND, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tereza, Č.; Milan, Š. Estimation of alcohol demand elasticity: Consumption of wine, beer, and spirits at home and away from home. J. Wine Econ. 2022, 17, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.; Saloner, G. Standardization, compatibility, and innovation. Rand J. Econ. 1985, 16, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannock, G. The Economics and Management of Small Business; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.P.T. Firms’ market power, endogenous preferences and the focus of competition policy. Rev. Political Econ. 2000, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Research Network Statistical Database. 2024. Available online: https://www.drcnet.com.cn (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Economy Prediction System Database. 2024. Available online: http://www.epsnet.com.cn/index.html (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Yumkella, K.K.; Unnevehr, L.J.; Garcia, P. Noncompetitive pricing and exchange rate pass-through in selected U.S. and Thai rice markets. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1994, 26, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, F.; Yin, Z.H.; Gan, J.B. Exchange-rate fluctuation and pricing behavior in China’s wood-based panel exporters: Evidence from panel data. Can. J. For. Res. 2017, 47, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau Van Dijk EIU Countrydata Database. 2024. Available online: https://eiu.bvdep.com/countrydata/ip (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Varma, P.; Issar, A. Pricing to market behaviour of India’s high value agrifood exporters: An empirical analysis of major destination markets. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P.; Gorton, M.; Hubbard, C.; Hubbard, L. Pricing-to-market analysis: The case of EU wheat exports. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 68, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manitra, A.R.; Shapouri, S. Market power and the pricing of commodities imported from developing countries: The case of US vanilla bean imports. Agric. Econ. 2001, 25, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, G.; Mullen, J. Pricing-to-market in NSW rice export markets. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2001, 45, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pall, Z.; Perekhozhuk, O.; Teuber, R.; Glauben, T. Are Russian wheat exporters able to price discriminate? Empirical evidence from the last decade. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 64, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, P.K.; Hellerstein, R. A structural approach to explaining incomplete exchange-rate pass-through and pricing-to-market. Am. Econ. Assoc. 2008, 98, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deaton, A.; Muellbauer, J. An almost ideal demand system. Am. Econ. Rev. 1980, 70, 312–326. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, K.W.; Shin, Y.M. Comparative analysis of import substitution relations of frozen squid demand. J. Fish. Bus. Adm. 2022, 53, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, S.; Schrobback, P.; Hoshino, E.; Curtotti, R. Impact of changes in imports and farmed salmon on wild-caught fish prices in Australia. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2023, 50, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Pettersen, I.K.; Myrland, O. Satisfying Norwegian appetites: Decoding regional demand for shrimp. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgenie, D.; Khoiriyah, N.; Mahase-Forgenie, M.; Adeleye, B.N. An error-corrected linear approximate almost ideal demand system model for imported meats and seafood in Indonesia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, D.; Jimenez-Toribio, R.; Guillotreau, P.; Anastacio-Solis, J. The ex-vessel market for tropical tuna in Manta, Ecuador. A new key player on the global tuna market. Fish. Res. 2023, 262, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.F.; Chen, Y.J.; Chang, K.I. Modeling import demand for fishery products in Japan: A dynamic AIDS approach. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2023, 38, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obidzinski, K.; Andrianto, A.; Wijaya, C. Cross-border timber trade in Indonesia: Critical or overstated problem? Forest governance lessons from Kalimantan. Int. For. Rev. 2007, 9, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, J.C. Value-Added Timber Processing in 21st Century Russia: An Economic Analysis of Forest Sector Policies; University of Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.J.; Liu, Q.; Dong, S.C.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tsydypov, B.; Bilgaev, A.; Ayurzhanaev, A.; Bu, X.Y.; et al. Investment environment assessment and strategic policy for subjects of federation in Russia. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.B.; Xia, Q.; Kang, C.Q.; Jiang, J.J. Novel approach to assess local market power considering transmission constraints. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2008, 30, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, S.P.; Raglend, I.J.; Kothari, D.P. A review on market power in deregulated electricity market. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2013, 48, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.K.; Cubbage, F.W.; Gonzalez, R.; Abt, R.C. Assessing market power in the US pulp and paper industry. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 102, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.C.; Hong, Q.; Han, X. Neoliberal conservation in REDD plus: The roles of market power and incentive designs. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.Y.; Xu, Y. Design of robust var reserve contract for enhancing reactive power ancillary service market efficiency. Csee J. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 10, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kuuluvainen, J.; Lin, Y.; Gao, P.H.; Yang, H.Q. Cointegration in China’s log import demand: Price endogeneity and structural change. J. For. Econ. 2017, 27, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, M.C.; Tudor, E.M. State of the art of the Chinese forestry, wood industry and its markets. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 17, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gan, J.B. Who will Meet China’s Import Demand for Forest Products? World Dev. 2007, 35, 2150–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; He, J. Linking the past to the future: A reality check on cross-border timber trade from Myanmar (Burma) to China. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 87, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhu, C. China’s wood-based forest product imports and exports: Trends and implications. Int. For. Rev. 2023, 4, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, B.D.; Diao, G.; Tao, C.L.; Wang, C. Does China’s natural forest logging ban affect the stability of the timber import trade network? For. Policy Econ. 2023, 152, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, S. Wood trade responses to ecological rehabilitation program: Evidence from China’s new logging ban in natural forests. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 122, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niquidet, K.; Tang, J.W. Elasticity of demand for Canadian logs and lumber in China and Japan. Can. J. For. Res. 2013, 43, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.D.; Qin, G.Y.; Song, W.M. Analysis of the log import market and demand elasticity in China. For. Chron. 2015, 91, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.L.; Niquidet, K. Elasticity of import demand for wood pellets by the European Union. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 81, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.J.; Zhang, Y. The impact of changes in log import price from the logging ban on the market price of timber products. J. Sustain. For. 2023, 42, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| εjt | ERPT* | The Import Price in Foreign Currency | PTM* (φj) | The Import Price in Local Currency | Exchange Rate Pass-Through and Market Power (China’s Imports) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfectly inelastic (εjt = 0) | >0 | Increase | >1 | Increase > exchange rate fluctuation | Reverse pass-through of exchange rates, no market power |

| Perfectly inelastic (εjt = 0) | =0 | Remain unchanged | =1 | Increase = exchange rate fluctuation | Complete non-pass-through of exchange rates, no market power |

| Lack of elasticity (0 < εjt < 1) | (−½, 0) | 0 < decrease < ½ of the exchange rate fluctuation | (½, 1) | ½ < increase < exchange rate fluctuation | Incomplete pass-through of exchange rates, relatively weak market power |

| Unit elasticity (εjt = 1) | =−½ | Decrease = ½ of the exchange rate fluctuation | =½ | Increase = ½ of exchange rate fluctuation | Incomplete pass-through of exchange rates, equal market power |

| Highly elastic (εjt > 1) | (−1, −½) | ½ < decrease < exchange rate fluctuation | (0, ½) | 0 < increase < ½ of exchange rate fluctuation | Incomplete pass-through of exchange rates, relatively strong market power |

| Infinite elasticity (εjt → ∞) | =−1 | decrease = exchange rate fluctuation | =0 | Remain unchanged | Complete pass-through of exchange rates, strong market power |

| Infinite elasticity (εjt → ∞) | <−1 | decrease > exchange rate fluctuation | <0 | Decrease | Excessive pass-through of exchange rates, dominant market power |

| Variables Name | Fisher-Type | Levin–Lin–Chu | Consequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p Value | Z Value | L* Value | Pm Value | t Value | ||

| lnrlp | 494.94 *** | −18.03 *** | −31.37 *** | 52.41 *** | −6.60 *** | Stable |

| lnelp | −78.91 *** | −4.67 *** | −4.55 *** | 4.69 *** | −1.65 *** | Stable |

| Variables Name | Pedroni Residual | Kao Residual | Consequence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rho Value | PP Value | ADF Value | t Value | ||

| Lnrlp and lnelp | −57.67 *** | −25.97 *** | −13.57 *** | −2.85 *** | There exists a cointegration relationship |

| Import Source | Nominal Exchange Rate | Real Exchange Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERPT* | PTM* (φj) | Market Power | ERPT* | PTM* (φj) | Market Power | |

| Indonesia | −2.94 | −1.94 *** | Superlative | −2.51 | −1.51 *** | Superlative |

| Malaysia | −2.40 | −1.40 *** | Superlative | −2.41 | −1.41 *** | Superlative |

| Myanmar | −1.20 | −0.20 *** | Superlative | −1.21 | −0.21 *** | Superlative |

| Russia | −0.95 | 0.05 ** | Strong | −0.94 | 0.06 *** | Strong |

| The DRC | −0.88 | 0.12 *** | Strong | −0.88 | 0.12 *** | Strong |

| Mozambique | −0.57 | 0.43 *** | Strong | −0.51 | 0.49 *** | Strong |

| Papua New Guinea | −0.43 | 0.57 *** | Weak | −0.34 | 0.66 *** | Weak |

| Equatorial Guinea | −0.19 | 0.81 *** | Weak | −0.09 | 0.91 *** | Weak |

| France | −0.18 | 0.82 *** | Weak | −0.30 | 0.70 *** | Weak |

| Germany | −0.08 | 0.92 *** | Weak | −0.09 | 0.91 *** | Weak |

| Australia | −0.07 | 0.93 *** | Weak | −0.14 | 0.86 *** | Weak |

| New Zealand | −0.01 | 0.99 *** | Weak | −0.21 | 0.79 *** | Weak |

| Japan | 0.19 | 1.19 *** | No | 0.14 | 1.14 *** | No |

| Cameroon | 0.47 | 1.47 *** | No | 0.38 | 1.38 *** | No |

| The United States | 3.14 | 4.14 *** | No | 2.46 | 3.46 *** | No |

| Laos | −2.19 | −1.19 | Not significant | −2.87 | −1.87 | Not significant |

| The Solomon Islands | −1.36 | −0.36 | Not significant | −1.25 | −0.25 | Not significant |

| Gabon | −1.21 | −0.21 | Not significant | −1.47 | −0.47 | Not significant |

| Canada | −1.05 | −0.05 | Not significant | −1.23 | −0.23 | Not significant |

| R2 = 0.79 | R2 = 0.78 | |||||

| Log Likelihood = −788.09 | Log Likelihood = −914.77 | |||||

| F-statistic = 57.54 | F-statistic = 53.47 | |||||

| Prob (F-statistic) = 0.00 | Prob (F-statistic) = 0.00 | |||||

| Expenditure Elasticity | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ | ⑩ | ⑪ | ⑫ | ⑬ | ⑭ | ⑮ | ⑯ | ⑰ | ⑱ | ⑲ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ① | 1.47 | −0.73 | −0.03 | 0.18 | −0.37 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.19 | −0.14 | 0.16 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.29 | −0.30 | −0.16 | −0.24 | 0.21 | −0.08 |

| ② | 1.09 | −0.01 | −0.26 | −0.01 | −0.20 | −0.58 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.21 | 0.05 | −0.78 | 0.11 | −0.07 | −0.01 | −0.17 | 0.25 | −0.45 | −0.17 | 0.26 | −0.30 |

| ③ | 0.04 | 0.19 | −0.01 | −1.25 | −0.02 | −0.12 | 0.47 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.37 | 0.26 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.57 | −0.05 | −0.37 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.02 |

| ④ | 1.21 | −0.55 | −0.42 | −0.04 | −0.67 | −0.14 | 0.60 | −0.30 | −0.16 | −0.16 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.24 | −1.84 | 0.32 | 1.63 | −0.03 |

| ⑤ | 1.46 | 0.08 | −0.22 | −0.12 | −0.09 | −0.29 | −0.21 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.44 | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.13 | −0.16 | −0.18 | −0.39 | −0.54 |

| ⑥ | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.40 | −0.21 | −1.37 | 0.30 | 0.19 | −0.03 | −0.12 | −0.14 | −0.23 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.54 | −1.01 | 0.51 | −0.62 | −0.01 |

| ⑦ | 1.19 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.22 | −0.03 | 0.33 | −0.79 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.87 | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.12 | −0.08 | −0.59 | −0.17 | −0.30 | −0.48 |

| ⑧ | 1.85 | −0.20 | 0.30 | −0.02 | −0.25 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.18 | −0.38 | −0.12 | 0.31 | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.32 | 0.14 | −0.54 | −2.71 | −0.29 | 1.05 | −0.26 |

| ⑨ | 1.03 | −1.01 | 0.08 | 0.57 | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.00 | 0.08 | −0.31 | −0.19 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.00 | −0.16 | −0.00 | −0.04 | −0.13 | −0.03 | 0.45 |

| ⑩ | 1.58 | −0.14 | −1.12 | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.66 | 0.13 | 0.18 | −0.67 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.29 | 0.66 | −0.31 | −1.31 | −1.41 | −0.10 | 0.21 |

| ⑪ | −0.92 | 0.61 | 0.63 | −0.12 | −0.06 | 1.01 | 0.52 | −0.25 | −0.07 | 0.22 | 0.51 | −1.24 | 0.43 | 0.71 | −0.37 | 0.13 | 0.31 | −0.36 | −0.81 | −0.27 |

| ⑫ | 1.85 | 0.03 | −0.73 | 0.27 | −0.23 | 0.03 | −1.57 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.51 | 0.83 | −0.87 | −0.89 | 0.16 | −0.17 | 2.62 | −0.62 | −0.25 | −0.65 |

| ⑬ | 1.65 | −0.45 | −0.18 | −0.35 | 0.42 | −0.26 | 1.69 | −0.44 | −0.86 | −0.23 | −1.96 | 1.36 | −0.49 | −0.42 | −0.23 | 0.36 | −0.78 | 0.65 | −0.96 | −0.50 |

| ⑭ | 0.68 | 0.31 | −0.13 | −0.32 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.16 | −0.26 | 0.74 | −0.09 | 0.21 | −0.10 | −1.67 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 0.04 | −0.84 | 0.14 |

| ⑮ | 0.98 | −0.41 | 0.29 | −0.07 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.76 | −0.10 | −0.29 | −0.05 | −0.42 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.14 | −2.07 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.38 | −0.13 |

| ⑯ | 1.46 | −0.41 | −0.29 | −0.07 | −0.22 | −0.21 | −0.76 | −0.10 | −0.29 | −0.15 | −0.42 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.14 | −0.07 | −0.44 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.09 |

| ⑰ | 1.14 | −0.07 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.19 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.50 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.26 | −0.56 | −0.23 | 0.11 |

| ⑱ | 0.64 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.23 | −0.33 | −0.11 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.27 | 0.03 | 0.13 | −0.03 | −1.47 | 0.29 |

| ⑲ | 1.55 | −0.03 | −0.17 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.22 | −0.02 | −0.16 | −0.03 | 0.19 | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.69 | 0.09 | 0.92 | −0.23 |

| Breusch−Pagan test of independence: χ2(171) = 895.36, p = 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Cheng, B.; Tian, M.; Meng, X. Measurement and Validation of Market Power in China’s Log Import Trade—Empirical Analysis Based on PTM Model and AIDS Model. Forests 2024, 15, 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15101792

Wang F, Cheng B, Tian M, Meng X. Measurement and Validation of Market Power in China’s Log Import Trade—Empirical Analysis Based on PTM Model and AIDS Model. Forests. 2024; 15(10):1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15101792

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fang, Baodong Cheng, Minghua Tian, and Xiao Meng. 2024. "Measurement and Validation of Market Power in China’s Log Import Trade—Empirical Analysis Based on PTM Model and AIDS Model" Forests 15, no. 10: 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15101792

APA StyleWang, F., Cheng, B., Tian, M., & Meng, X. (2024). Measurement and Validation of Market Power in China’s Log Import Trade—Empirical Analysis Based on PTM Model and AIDS Model. Forests, 15(10), 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15101792