1. Introduction

The escalation of global warming, caused by extensive greenhouse gas emissions, results in the degradation of the ecological environment on a global scale, posing threats to our survival [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Plants play a crucial role in the global carbon cycle. As forest plants grow and eventually decompose, carbon undergoes a continuous cycle of fixation and emission. Due to exceptionally long life cycles, with carbon accumulating over extended periods, ancient trees play a crucial role in long-term carbon sequestration [

7,

8,

9]. In urban spaces, gardening trees serve primary carbon sequestration roles [

10,

11,

12]. The identification of species with robust carbon sequestration capabilities supports the establishment of plant communities with high carbon sequestration in the long term. This can effectively contribute to carbon neutrality targets [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Investigating the features of the long-term carbon storage capacity of ancient garden trees is instrumental in devising sustainable development strategies and plans for long-term carbon sequestration.

Currently, research surrounding the carbon sequestration of vegetation covers three main aspects of the process. The first is the research on the carbon sequestration and oxygen emitting ability based on the short-term measurement of photosynthesis [

17,

18]. Bahtiar et al. [

19] use a sinusoidal equation to fit the daily photosynthesis light response curve of Betung Bamboo, and the fitting result was used to estimate the total carbon sequestration over the year. Piper et al. [

20] performed measurements for nonstructural leaf carbohydrates and gas exchange parameters to evaluate the carbon sequestration limitations of Kageneckia angustifolia at different altitudes. The results performed well in explaining the tree-line formation in the Mediterranean-type climate zone of central Chile. Gavito et al. [

21] led two experiments that were designed to investigate whether the manipulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal carbon sequestration significantly affects the photosynthetic rate of the treated plant. Hussey and Long [

22] used a dry matter accumulation method to evaluate the monthly changes in dry and ash-free dry weights per unit area of both the above- and belowground organs of the higher plants of an intertidal salt marsh.

The second aspect covered in the literature is mid-term carbon sequestration analyses based on the biomass of growth across seasons or years [

23,

24,

25]. Through large-scale field investigations, used to approach fundamental datasets, including standing volume datasets, a biomass evaluation model can be applied to estimate the mass of all possible storages in an ecosystem [

26]. Fang et al. [

27] estimated the terrestrial vegetation carbon sequestration performed for China’s major biomass between 1981 and 2000 using ground observations. It was found that forest biomass carbon stock increased from 4.3 PgC to 5.9 PgC.

The third aspect is the long-term global carbon sequestration and resource supply analyses based on model simulations [

23]. The model includes not only a statistical model based on experience data, but the biomass conversion process as well [

28]. Hester [

29] designed the ORGANON V2.0 software to project the changes that take place in mixed conifers in the young-growth forests stands of southwest Oregon. Cousar et al. [

30] reported a policy analysis for the Sierra Nevada ecosystem in central California. The indicator variables include the number of large trees, the basal area, the stand and harvest volume, the present net value, and a fire hazard index based on a forest vegetation simulator.

However, for ancient garden trees (age above 100 years), the carbon sequestration feature remains unclear [

31,

32,

33]. There are conflicting conclusions. Luyssaert et al. [

34] reported that unmanaged, old-growth forests continue to sequester atmospheric carbon at a rate of 2.4 Mg C ha

−1 year

−1 for stand ages exceeding 200 years based on an analysis of net ecosystem productivity and other C flux data from temperate or boreal forest plots compiled from published studies and databases; meanwhile, Gundersen et al. [

35] pointed out that the NEP data used in the analysis of Luyssaert, Schulze, Börner, Knohl, Hessenmöller, Law, Ciais, and Grace [

34] appeared to contain overestimates and, thus, the quantitative estimates of C sequestration in old-growth forests are suspect.

According to the abovementioned aspects, there is a general lack of data and models for carbon sequestration features of ancient garden trees. It is necessary to carry out basic analysis towards the carbon sequestration features, adding up to the basic data and model sets.

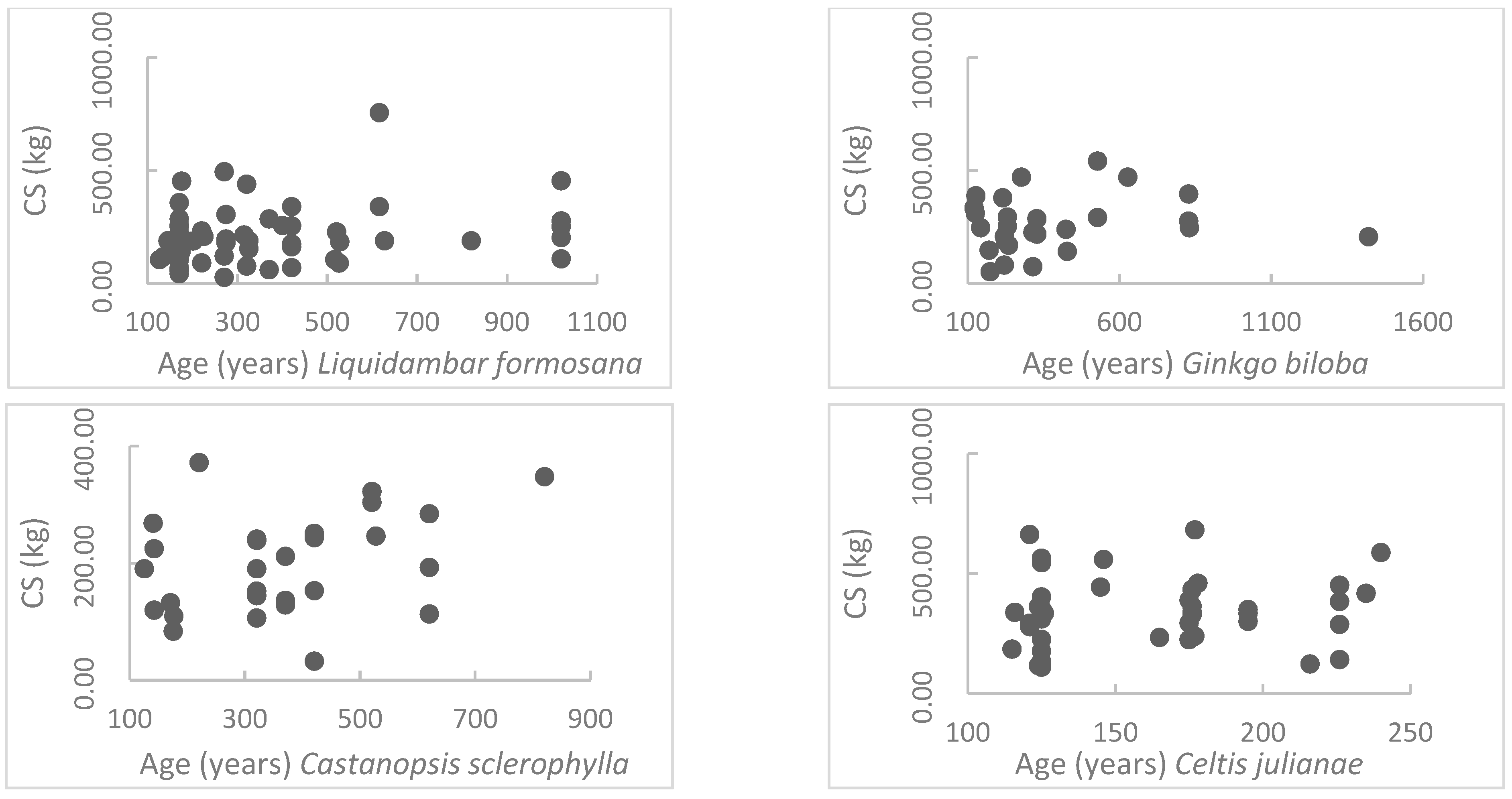

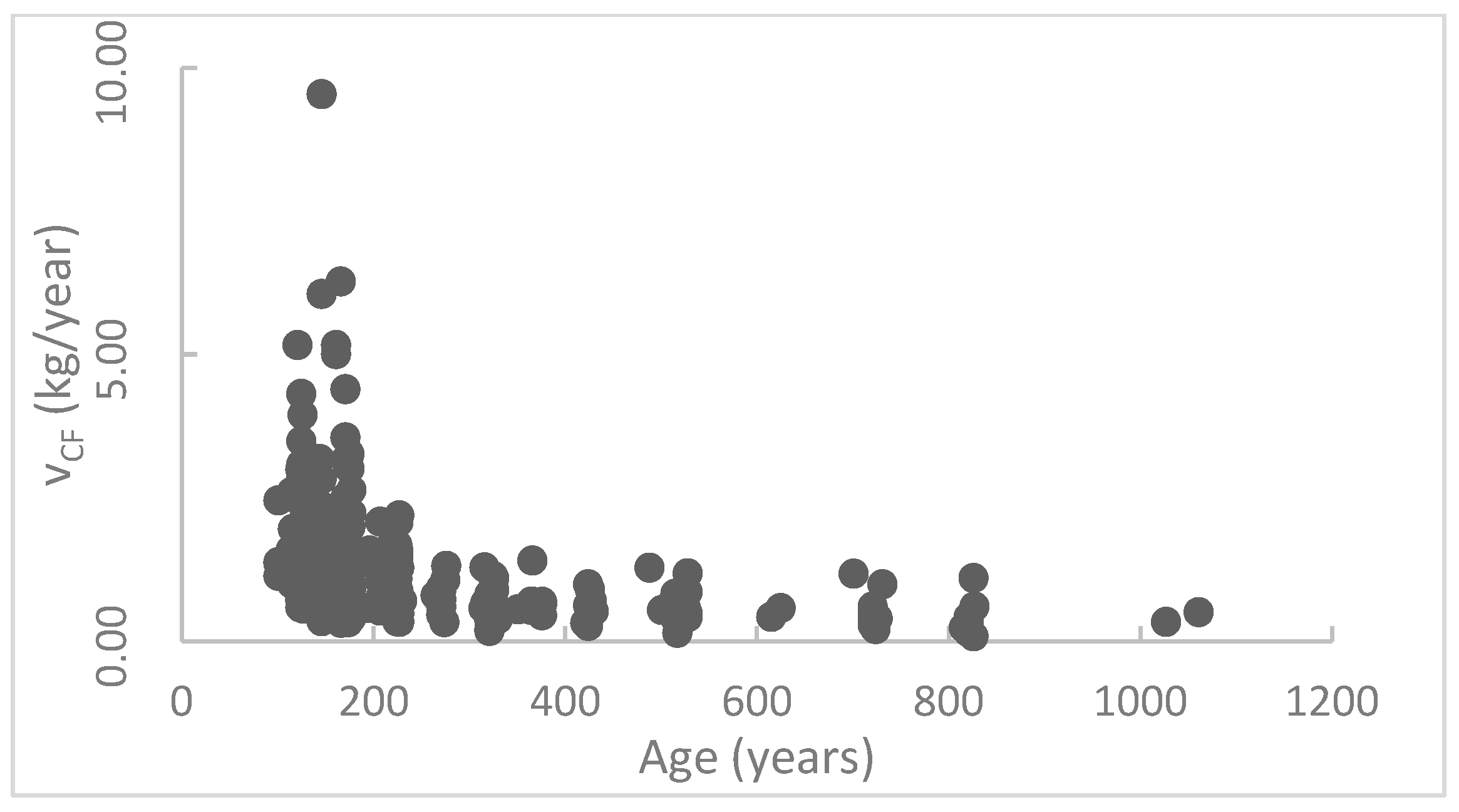

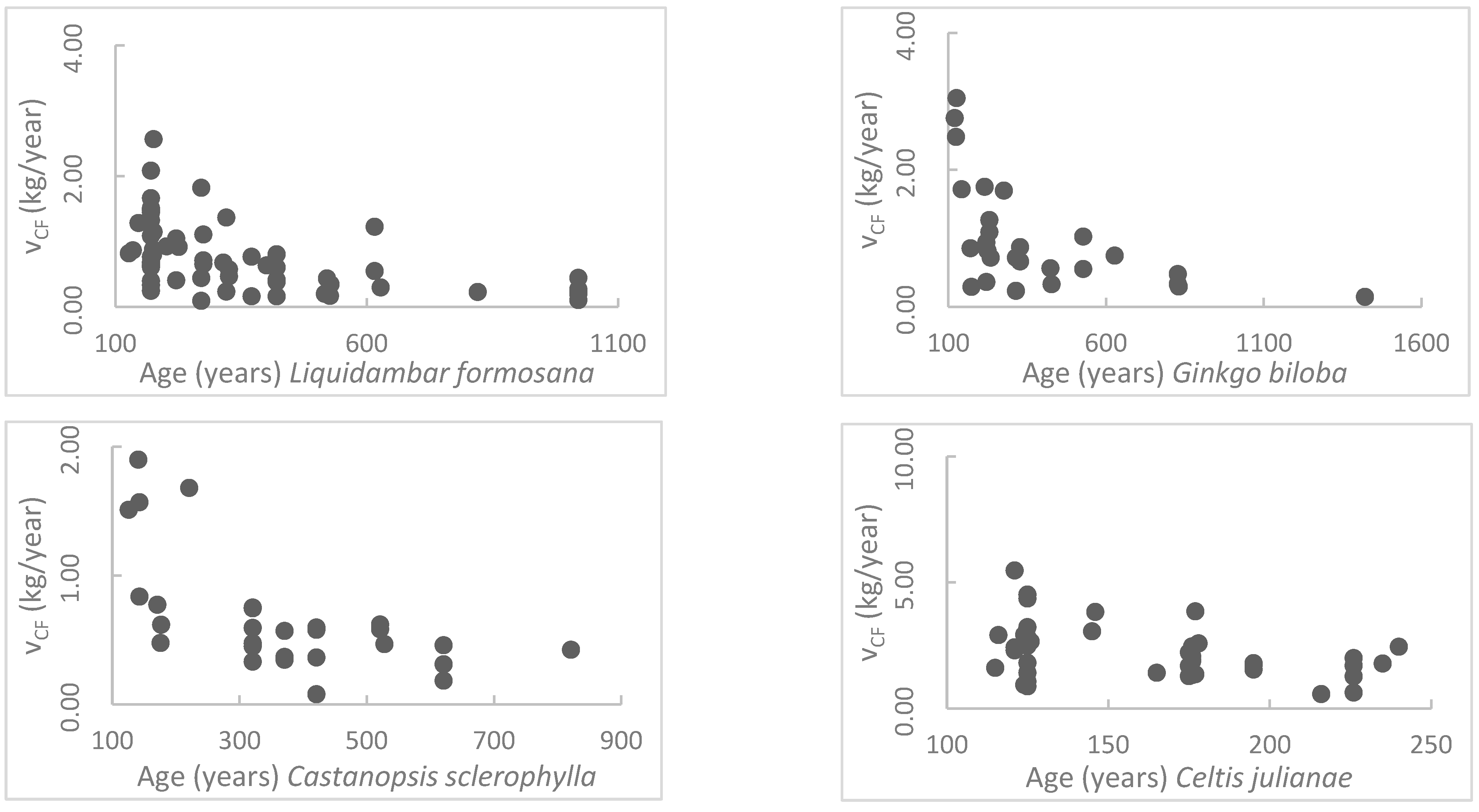

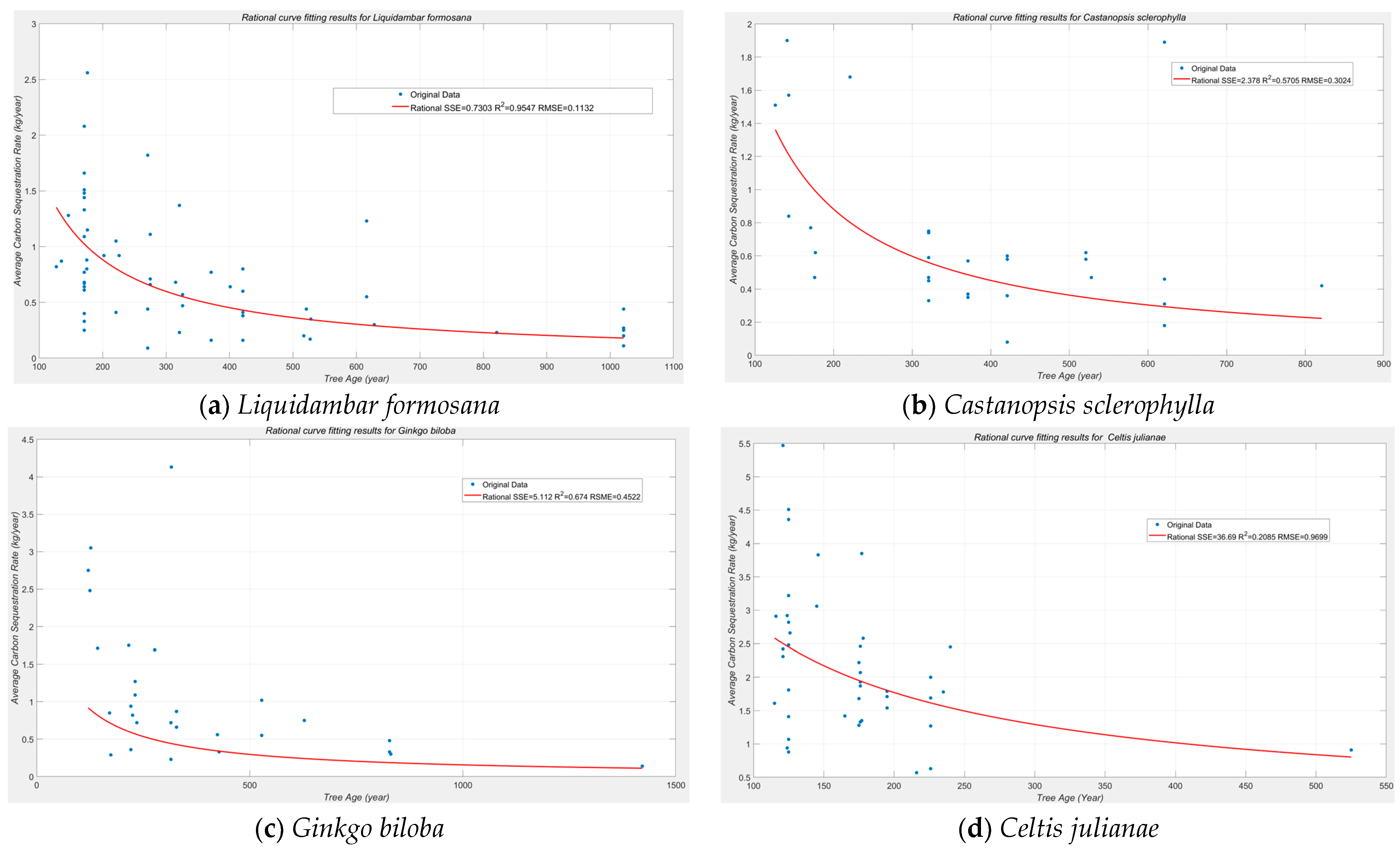

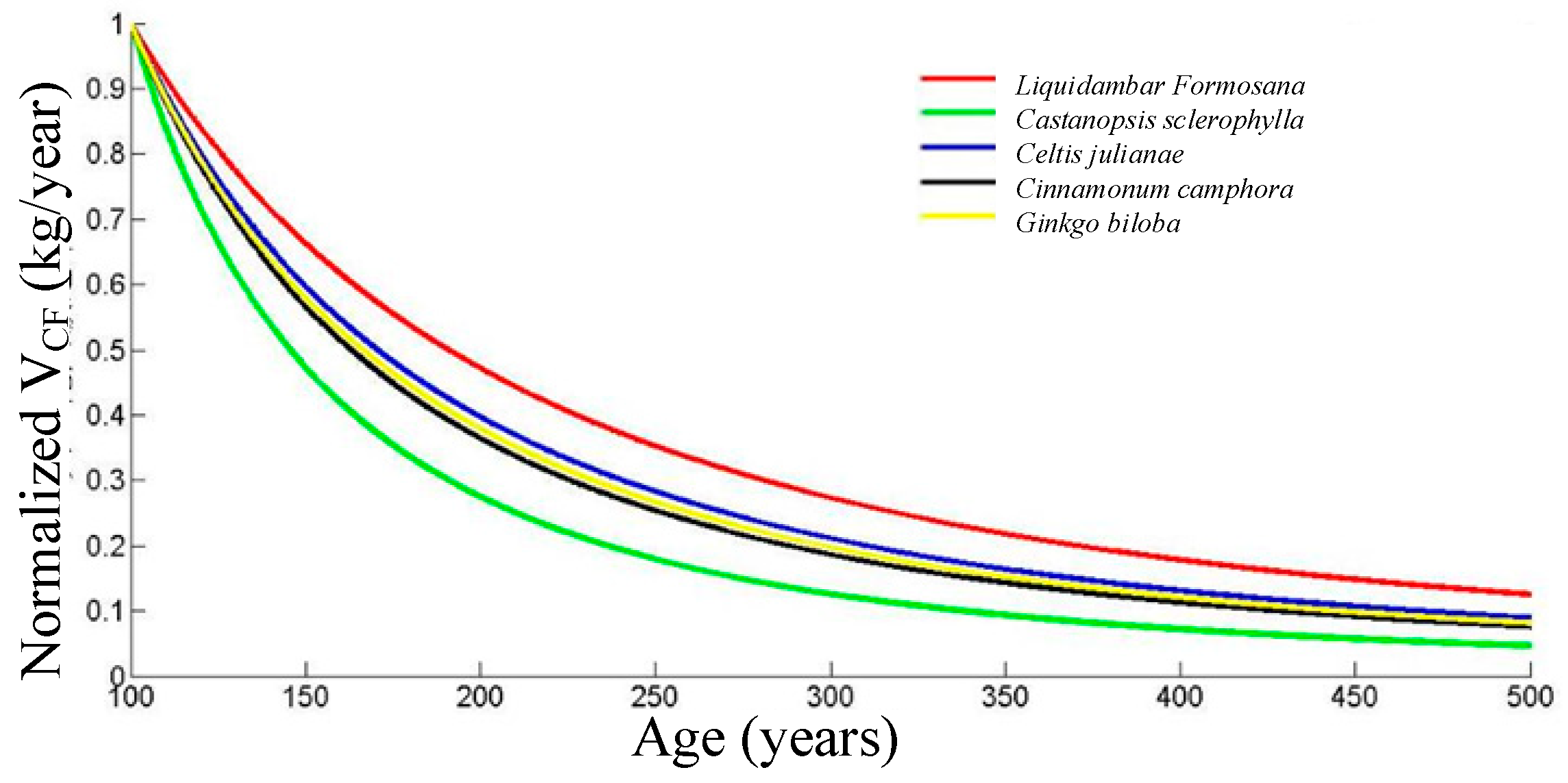

This research focuses on this topic and performs a detailed field investigation of more than 640 ancient individual garden trees that are widely utilized in urban greening with an age span between 100 and 1000 years in the West Lake Scenic Area, Hangzhou, China. Using dimension measurements and biomass calculations, the carbon sequestration data of each ancient tree are calculated. Then, statistical analyses, including regress modeling and normalized comparisons, based on age interval classification, are performed. Finally, ancient tree carbon sequestration models of five common species are built. The carbon sequestration abilities of more than 60 species are presented. The results provide the models of annual carbon sequestration rate and total carbon storage of the ancient trees, reflecting the carbon sequestration abilities of the plants.

4. Discussion

The results in this research reflect that the annual carbon sequestration rates of the ancient trees reduce with their ages. This is similar to the common regularities of most creatures [

42,

43]. Limited by the ability of self-weight bearing, resistance of natural disasters, and disease fighting, the total size of the ancient trees cannot increase linearly [

44]. Thus, the carbon sequestration rate decreases. The CS model in this research is different from the logistic model for forests within 5–10 years. The model proposed in this research is more appropriate for trees aged 100–1000 years, living in an environment with more human activity.

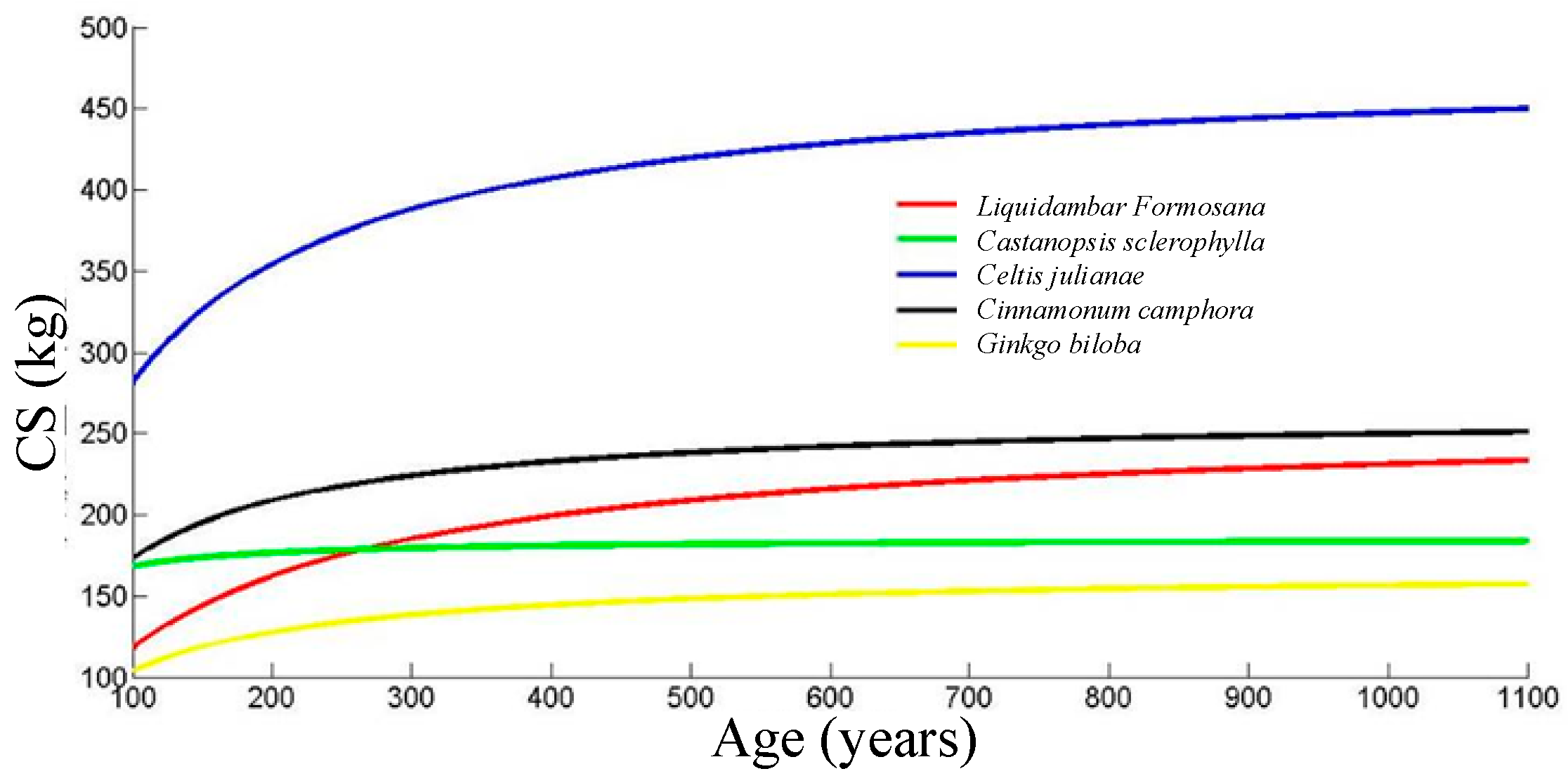

According to the expression of

CS(t), the total carbon sequestration of the ancient trees has an upper limit. The limitation can be calculated by (11), and the result is b

0. Over a long span of time, the ancient trees are always carbon sequesters rather than sources. The ancient trees can well limit the carbon captured and serve as stable holds. Continuous protection of the ancient trees is important and necessary to prevent reemission. The results also comply with the research of Brienen et al. [

45], who pointed out that there is an upper limitation of carbon sequestration. It was concluded in their research that although extant models predict that the density of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and global warming will continue to cause a net carbon uptake this century, there are indications that increased growth rates may shorten the lifespan, and, thus, recent increases in forest carbon stocks may be transient due to lagged increases in mortality.

For different tree species, the time (in year) to reach half of such a limitation can be calculated by (12); the result is parameter a

0. In long-term carbon sequestration planning, the species with high b

0 and low a

0 are recommended. For mature trees, the rate of carbon sequestration decreases with the year. Especially, the rate of carbon sequestration is low. Although the trees need protection, low-emission maintenance technologies are recommended. A reconsideration of forest development and use according to such a feature can be further set up to increase the efficiency of resource application [

46].

Although the biomasses of the ancient trees in this research were measured and calculated, the research still has some limitations. Within such a long period of time, many of the samples in this research experienced thunder, storms, and illness. The biomasses of fallen stem and leaves through years were huge. Although part of that was emitted back into the atmosphere, massive carbon was still fixed in the soils around the trees. Mixed with the biomasses from the surrounding trees, such carbon sequestration cannot be accurately calculated. It can be deducted that the ancient trees bring more carbon sequestration on Earth than the normal trees, as they live longer and accumulate more. The model deviation features in other regions than Hangzhou are still unknown. This can be carried out in future research.

5. Conclusions

Targeting at evaluating the carbon sequestration abilities of the ancient garden trees, the carbon sequestration data of 643 ancient trees were calculated using comprehensive field surveys. By statistical analysis, the long-term carbon sequestration ability ranking (from high to low) of the five most common garden tree species in Hangzhou area is Celtis julianae, Cinnamomum camphora, Castanopsis sclerophylla, Liquidambar formosana, and Ginkgo biloba (100 < age < 260 years). After 260 years, the ranking is Celtis julianae, Cinnamomum camphora, Liquidambar formosana, Castanopsis sclerophylla, and Ginkgo biloba.

For the tree species with limited sample numbers, the total carbon sequestration model of Cinnamomum camphora was used as a reference to conduct a comparative analysis across species. The findings indicate that the long-term carbon sequestration capacities of six species exceed that of Cinnamomum camphora; they are Quercus glauca, Machilus japonica, Celtis sinensis, Juniperus chinensis, Osmanthus, and Aphananthe aspera. The long-term carbon sequestration capacities of the other 49 species were lower than that of Cinnamomum camphor. According to the conclusions, in future urban space greening, Castanopsis sclerophylla, Liquidambar Formosana, and Osmanthus fragrans are recommended as they can better fix carbon in the long term. Especially, Castanopsis sclerophylla stores almost twice the carbon of Cinnamonum camphora. Meanwhile Liquidambar Formosana and Osmanthus fragrans provide special landscape features of colorful leaves and floral scent with relatively high carbon sequestration as well.