Redrawing the History of Celtis australis in the Mediterranean Basin under Pleistocene–Holocene Climate Shifts

Abstract

1. Introduction

Celtis australis: Species Description, Ecology and Traditional Uses

2. Materials and Methods

- We conducted literature searches to gather all the palaeobotanical finds of Celtis spp., from Lower Pleistocene to Middle Holocene. Regarding the geographical setting, we focused on the Mediterranean Basin and northern Europe, although we considered the findings in other regions, which could enrich our discussion. We gathered the documentation of macro-—wood, leaves, wood charcoal and seeds—and micro-remains—pollen and phytoliths—recovered in archaeological and natural sites.

- The palaeobotanical data are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, chronologically arranged. The chronology shown is that of the level or structure where the remains were recovered, not a direct dating (with exceptions). Where possible, the abundance of the taxon in the assemblage is noted, expressed as percentage or number of remains, as is published in the checked works.

- To check the antiquity of Celtis remains, we carried out two radiocarbon datings on uncharred endocarps from two Middle Palaeolithic Iberian sites: Abrigo de la Quebrada (Chelva, Valencia) and Cueva del Arco (Cieza, Murcia). Hackberry endocarps formed naturally with carbonate, which reflects the C14 atmospheric values of only one growing season. Therefore, endocarps are suitable for obtaining reliable dating [31]. However, the integrity of the mineral composition of the fossil specimen must be evaluated previously. The carpological remains were first washed with deionised water to remove organic sediments and debris. After crushing them, they were subjected to HCl etches to eliminate secondary carbonate components [32].

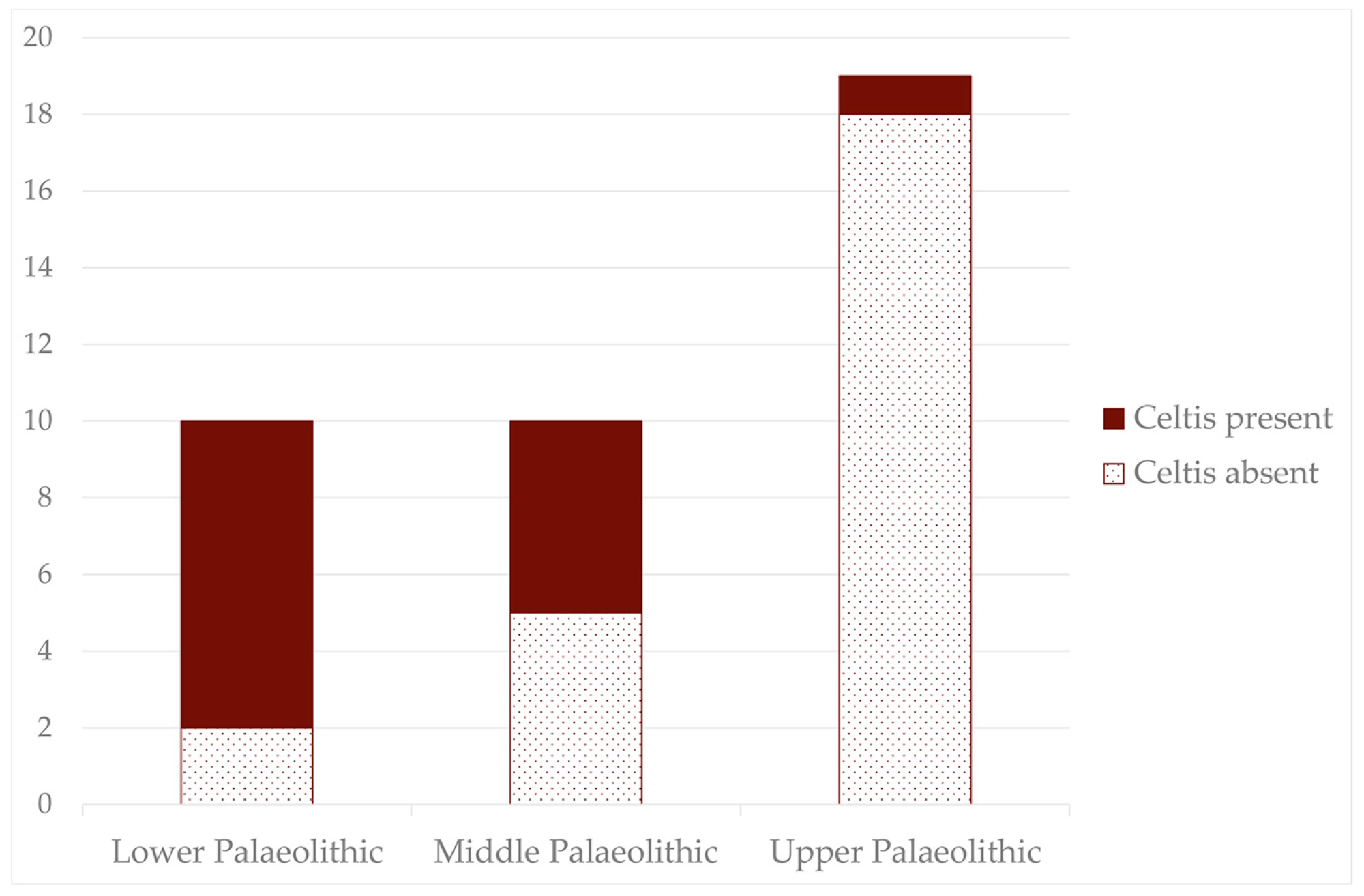

- The presence or absence of Celtis wood charcoal in archaeological sites is analysed to assess the specialised use of this taxon, considering the frequent presence of fruit remains as opposed to the absence of wood in most sites.

- A chemical analysis of the current fruits of Celtis australis was carried out to assess their nutritional value.

2.1. Celtis Endocarps Description

2.2. Challenges in Wood Celtis Identification

2.3. Chemical Composition Analysis

2.3.1. Morphological Parameters

2.3.2. Nutritional Parameters

3. Results

3.1. Palaeobotanical Remains

| ID | Site | Location | Chronology | Cultural Adscription | Taxa | Type | NR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bernasso | Lunas, France | 2.2 Ma–2.1 Ma (MIS 82–78) Pollen zone II = Interglacial | Celtis sp. | P | <15% | [48,49,50] | |

| L | ||||||||

| Celtis cf. australis/caucasica | ||||||||

| 2 | Tres Pins | Porqueres, Spain | Early Pleistocene (interglacial) | Celtis sp. | P | <2% | [51] | |

| 3 | Lamone Valley | Lamone Valley, Italy | 1.8–1.4 Ma (MIS 64-46) | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [52] | |

| 4 | Dmanisi | Kvemo Kartli, Georgia | 1.8 ± 0.05 Ma | Early Palaeolithic | Celtis sp. (cf. C. tournefortii) | E | 3 | [46] |

| 5 | Leffe Basin | Leffe, Italy | MIS 53-52 or 51-50 | Celtis sp. | P | <2% | [53] | |

| 6 | Palominas | Baza, Spain | 1.8–1.1 Ma | Celtis sp. | P | 10% | [8] | |

| 7 | Saint-Macaire maar | Servian, France | 1.4–0.68 Ma | Celtis sp. | P | <1% | [54] | |

| 8 | Cal Guardiola | Terrassa, Spain | 1.2–0.8 Ma | Celtis sp. | P | 0.2% | [55] | |

| 9 | Grotte du Vallonnet | Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France | 1,370,000 ± 120,000– 910,000 ± 60,000 BP (Donau-Günz Interglacial) | Celtis sp. | E | [47,56] | ||

| cf. Celtis australis | P | <5% | ||||||

| 10 | Gran Dolina | Atapuerca, Spain | 936,000 BP (MIS 25) | Lower Palaeolithic | Celtis cf. australis | E | 91 | [45,57] |

| P |

| ID | Site | Location | Chronology | Cultural Adscription | Taxa | Type | NR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | Łuków | Łuków, Poland | Ferdynandovian I interglacial (MIS 15–MIS 13) | Celtis sp. | P | [63] | ||

| 12 | Zdany | Zdany, Poland | Ferdynandovian I interglacial (MIS 15–MIS 13) | Celtis sp. | P | [63] | ||

| 13 | Achalkalakai | Achalkalakai, Georgia | Early Middle Pleistocene | Celtis sp. | E | [64] | ||

| 14 | Galería | Atapuerca, Spain | Final Middle Pleistocene | Lower Palaeolithic | Celtis sp. | P | 2% | [65] |

| 15 | Krzyżewo | Krzyżewo, Poland | Augustovian interglacial (cf. Late Cromerian) | Celtis sp. | P | <1% | [66] | |

| 16 | Grotte de l’Escale | Saint-Estève-Janson, France | Middle and Upper Mindel | Without adscription | Celtis sp. | E | [59] | |

| 17 | Grotte nº1 du Mas des Caves | Lunel-Viel, Hérault, France | 550,000–400,000 BP (Mindel–Riss Interglacial, MIS 11) | Middle Acheulean | Celtis sp. | E | [67] | |

| 18 | Ceprano | Ceprano, Italy | 530,000–380,000 BP (MIS 13) | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [68] | |

| 19 | Kleszczów Graben | Kleszczów, Poland | Ferdynandovian and Holsteinian interglacial | Celtis sp. | P | <1% | [69] | |

| 20 | Terra Amata * | Nice, France | 380,000 BP (MIS 11) | Acheulean | Celtis australis | E | De Lumley in Refs [60,61] | |

| 21 | Kärlich | Mülheim-Kärlich, Germany | Interglacial, MIS 11 | Early Palaeolithic | Celtis sp. | E | 1 | [58,70] |

| C and W | 27 | |||||||

| P | 1.4% | |||||||

| 22 | Munster/ Breloh | Niedersachsen, Lüneburger Heide, Germany | Holsteinian interglacial | Celtis sp. | E | Müller 1974 cited in Refs [70,71] | ||

| P | <5% | |||||||

| 23 | Southwestern Mecklenburg | Hagenow, Germany | Middle Pleistocene | Celtis sp. | E | Erd cited in Ref [70] | ||

| 24 | Dethlingen | Lüneburger Heide, Germany | Holsteinian interglacial | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [72] | |

| 25 | Döttingen | Rheinland-Pfalz, Eifel, Germany | Holsteinian interglacial | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [71] | |

| 26 | Bilzingsleben | Bilzingsleben, Germany | Holsteinian interglacial | Celtis sp. | P | [73] | ||

| 27 | Kreftenheye Formation | Raalte, The Netherlands | >MIS 5 (reworked, remains from older interglacials) | Celtis sp. | W | 1 | [74] | |

| 28 | La Celle-sur-Seine | Vernou-La Celle-sur-Seine, France | 425,000 ± 46,000 BP (MIS 11) | Celtis australis | L (impressions) | [75] | ||

| 29 | Caune de l’Arago | Tautavel, France | 320,000–220,000 BP | Acheulean | Celtis australis | E | De Lumley in Ref [60] | |

| 30 | Grotte du Lazaret | Nice, France | Late Middle Pleistocene (Riss I, II and III) | Acheulean | Celtis australis | E | De Lumley in Refs [60,61] | |

| 31 | La Rouquette | Millau, France | 273,000 ± 23,000 BP (MIS 7) | Celtis australis | E | 1 | [76] | |

| 32 | Coudoulous I | Tour-de-Faure, Lot, France | 300,000–200,000 BP | Celtis australis | E | Bonifay and Clottes 1981 in Ref [76] | ||

| 33 | Cova del Bolomor | Tavernes de la Valldigna, Spain | >350,000 BP (MIS 8-9) | Mousterian | Celtis australis | P | <3% | [62] |

| 233,000–152,000 (MIS 7) | E | |||||||

| 34 | Cova Negra | Xàtiva, Spain | 303,000–148,000 BP (MIS 6–8) | Mousterian | Celtis sp. | E | 25 | Unpublished |

| 35 | Meyrargues | Meyrargues, France | 170,000 and 145,000 BP | Celtis australis | L | [77] | ||

| 36 | Aygalades | Marsella, France | Middle Pleistocene | Celtis australis | L | [77,78] | ||

| 37 | Padul | Padul, Spain | 180,000 cal BP (MIS 6e) | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [79] |

| ID | Site | Location | Chronology | Cultural Adscription | Taxa | Type | NR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | Cova del Toll | Moià, Spain | MIS 5–6? | Middle Palaeolithic | Celtis sp. | P | <3% | [84] |

| 33 | Cova del Bolomor | Tavernes de la Valldigna, Spain | <121,000 BP (MIS 5e) | Mousterian | Celtis sp. | P | <3% | [83] |

| E | ||||||||

| 39 | Theopetra | Kalambaka, Greece | 129,000 ± 13,000 BP–57,000 ± 6000 BP (MIS 5-4) | Middle Palaeolithic | Celtis cf. tournefortii | E | 1 | [82,87] |

| Ph | <6% | |||||||

| 37 | Padul | Padul, Spain | 107,000–92,000 cal BP (MIS 5c and MIS 5b) | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [79] | |

| 40 | Lake Ohrid | FYROM | 131,000–69,900 BP (MIS 5 and early MIS 4) | Celtis sp. | P | [88] | ||

| 41 | Castelnau le Lez | Castelnau le Lez, France | 113,700 (+7200/−6700)–44,700 (+2100/−2000) BP (MIS 5-3) | Celtis australis | L | [78,89,90] | ||

| 42 | Douara Cave | Palmyra Basin, Syria | 52,000 (+5000/−3000) BP (MIS 3) * | Mousterian | Celtis cf. australis and C. cf. tournefortii | E | >127 | [81,91,92] |

| 43 | Abric de El Salt | Alcoi, Spain | 52,300 ± 4600 BP (MIS 3) | Mousterian | Celtis australis | E | 1 | [93,94] |

| Ph | ||||||||

| 44 | Cueva del Niño | Ayna, Spain | 55,550 BP (MIS 3) | Mousterian | Celtis sp. | E | 17 | [95] |

| 45 | Abrigo de la Quebrada | Chelva, Spain | 40,243–39,075 cal BP (MIS 3) * | Mousterian | Celtis sp. | E | 7 | [80] |

| 46 | Baaz | Damascus, Syria | 39,565–36,169 cal BP (MIS 3) | Upper Palaeolithic | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [96] |

| 47 | Cueva del Arco | Cieza, Spain | 36,091–35,203 cal BP (MIS 3) * | Mousterian | Celtis sp. | E | 10 | Unpublished |

| 48 | Straldzha Mire | Bulgaria | 37,500–17,900 cal BP (MIS 3-2) | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [97] | |

| 37 | Padul | Padul, Spain | 27,000–15,000 cal BP (MIS 2) | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [79] | |

| 49 | Teixoneres | Barcelona, Spain | 20,000–16,000 cal BP (MIS 2) | Upper Palaeolithic | Celtis sp. | P | <3% | [98] |

| 39 | Theopetra | Kalambaka, Greece | 20,000–12,000 cal BP (MIS 2) | Upper Palaeolithic | Celtis cf. tournefortii | E | 50 | [82,87] |

| Ph | <3% | |||||||

| 50 | Karain B | Antalya, Turkey | 19,899–18,991 cal BP (MIS 2) | Epipalaeolithic | Celtis sp. | E | 6 | [85] |

| 51 | Öküzini | Antalya, Turkey | 19,080–13,747 cal BP (MIS 2) | Epipalaeolithic | Celtis sp. | E | 380 | [85] |

| 52 | Pınarbaşı | Konya Plain, Turkey | 16,000–14,000 cal BP (MIS 2) | Epipalaeolithic | Celtis sp. | C | 1.09% | [99] |

| 53 | Ezero wetland | Nova Zagora, Bulgaria | 15,550–14,950 cal BP (MIS 2) * | Celtis sp. | P | 20% | [86] | |

| Celtis tournefortii tp. | E | 3 per 45 cm3 | ||||||

| Celtis sp. | W | 4 per 45 cm3 | ||||||

| 38 | Cova del Toll | Moià, Spain | <13,000 cal BP (probably MIS 1, but perhaps covers part of MIS 2) | Celtis sp. | P | <3% | [84] | |

| 54 | Tell Abu Hureyra | Euphrates Valley, Syria | 13,111 ± 94–11,981 ± 217 cal BP (MIS 2) | Epipalaeolithic | Celtis tournefortii | E | [100,101] | |

| 55 | Körtik Tepe | Diyarbakir/Batman, Turkey | 12,479–11,388 (MIS 2) | Epipalaeolithic | Celtis sp. | C | 1 (0.01%) | [102] |

| 56 | Bagnoli | San Gimignano, Italy | GI 1e and GI 1c (MIS 2) | Celtis sp. | P | <5% | [103] | |

| 57 | Pella | Ṭabaqat Faḥl, Jordan | MIS 2 | Kebarian | Celtis sp. | C | [104] |

| ID | Site | Location | Chronology | Cultural Adscription | Taxa | Type | NR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 | Tell Qaramel | Aleppo, Syria | 12,193–11,250 cal BP | Khiamian | Celtis sp. | E | 400 | [109] |

| 59 | Lago dell’Accesa | Massa Marittima, Italy | Ca. 11,650–11,350 cal BP | Celtis australis | P | [107] | ||

| 55 | Körtik Tepe | Diyarbakir/Batman, Turkey | 11,600–11,350 cal BP | Pre-Pottery Neolithic | Celtis sp. | C | 15 (0.8%) | [102] |

| 60 | Jerf el Ahmar | Middle, Euphrates, Syria | 11,400–10,255 cal BP | Pre-Pottery Neolithic | Celtis sp. | E | 1 | [109] |

| 39 | Theopetra | Kalambaka, Greece | 11,200–9200 cal BP | Mesolithic | Celtis cf. tournefortii | E | 35 | [82,87] |

| Ph | <5% | |||||||

| 61 | Shillourokambos | Parekklisha, Cyprus | 10,700–9529 cal BP | Pre-Pottery Neolithic | Celtis sp. | E | 2 | [110] |

| 62 | Klimonas | Ayios Tychonas, Cyprus | Late 11th–middle 10th millennium cal BP | PPNA | Celtis sp. | E | [111] | |

| 63 | Nevali Çori | Sanliurfa, Turkey | 10,350 cal BP | PPNB, PN | Celtis sp. | E | 1 | [112] |

| 64 | Asikli Höyük | Aksaray, Turkey | 10,220–9468 cal BP | Pre-Pottery Neolithic | Celtis cf. tournefortii | E | 17,885 | [113] |

| 65 | Çayönü | Diyarbakır, Turkey | 10,200–9700 cal BP | Pre-Pottery Neolithic | Celtis cf. tournefortii | E | 2 | [105] |

| 66 | Ganj Dareh | Kermanshah, Iran | 10,200–9560 cal BP | PPNB | Celtis sp. | C | [114] | |

| 67 | Lake Voulkaria | Acarnania, Greece | 9966–8171 cal BP | Celtis sp. | P | 5% | [115] | |

| 68 | Cave of Cyclops | Gioura, Greece | 9700–6700 cal BP | Late Mesolithic | cf. Celtis sp. | E | 1 | [116] |

| 69 | Lake Gorgo Basso | Sicily, Italy | 9785–9010 cal BP | Celtis australis | P | 5% | [108] | |

| 70 | Can Hasan III | Konya plain, Turkey | 9600–8400 cal BP | Aceramic Neolithic | Celtis cf. tournefortii | E | 978 | [99,117,118] |

| Celtis sp. | C | 0.31% | ||||||

| 71 | Çatalhöyük | Konya plain, Turkey | 9327–8171 cal BP | Early Neolithic | Celtis sp. (cf. C. tournefortii) | E | 1498 | [119] |

| C | 9.81%–5.44% | |||||||

| 72 | Hacilar | Burdur, Turkey | 9027–7780 cal BP | Late Neolithic | Celtis australis | E (charred) | 125 | [106] |

| 73 | Cafer Höyük | Malatya, Turkey | 8990–8150 cal BP | Early, Middle and Late PPNB | Celtis sp. | C | [104,120] | |

| Celtis sp. | E | 4 | ||||||

| Pistacia/Celtis sp. | E | 1 | ||||||

| 74 | Khirokitia | Larnaka, Cyprus | 9th–8th millennium cal BP | Late Aceramic Neolithic (Khirokitian) | Celtis sp. | E | 1 | [121,122] |

| 75 | Dhali-Agridhi (Idalion) | Dhali, Cyprus | c. 9th millennium cal BP | Late Aceramic Neolithic (Khirokitian) | Celtis sp. | E | 1 | [123] |

| 76 | Kholetria-Ortos | Paphos, Cyprus | 8550–7750 cal BP | Late Aceramic Neolithic (Khirokitian) | Celtis sp. | E | [124] |

| ID | Site | Location | Chronology | Cultural Adscription | Taxa | Type | NR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52 | Pınarbaşı | Konya plain, Turkey | 8395–6392 cal BP | Final Neolithic | Celtis sp. | C | 2.34% | [99,126] |

| Chalcolithic | 1.12% | |||||||

| 77 | Ramad | Damasco, Syria | 8250–7950 cal BP | PPNB | Celtis/Ulmus sp. | C | [118,127] | |

| 70 | Lake Gorgo Basso | Sicily, Italy | 8213–4402 cal BP | Celtis australis | P | <5% | [108] | |

| 78 | Aknashen | Ararat valley, Armenia | 7975–7157 cal BP | Neolithic | Celtis sp. | E | 5 | [128] |

| 79 | Aratashen | Ararat valley, Armenia | 7861–7428 cal BP | Neolithic | Celtis sp. | E | 1 | [128] |

| 80 | Kumtepe A | Troas, Turkey | 7435–6550 cal BP | Late Neolithic | Celtis sp. | C | 1.17% | [129] |

| 4950–4400 cal BP | Early Bronze Age | 0.82% | ||||||

| 81 | Lake Beloslav | Varna, Bulgaria | 6796–3874 cal BP | Celtis sp. | P | >1% | [130] | |

| 82 | Ayios Epiktitos-Vrysi | Kirenia, Cyprus | 6750–5750 cal BP | Late Aceramic Neolithic (Khirokitian) | Celtis australis | E | [124] | |

| 83 | Poças de São Bento | Torrão, Portugal | ca. 6550 cal BP | Early Neolithic | Celtis australis | E (charred) | 12 | [125] |

| 84 | Kissonerga-Mosphilia | Kissonerga, Cyprus | 6550–4150 cal BP | Chalcolithic (Early, Middle and Late) | Celtis sp. | E | 7 | [124,131] |

| 85 | Heraion of Samos | Kastro-Tigani, Samos, Greece | 5050–3950 cal BP | Early Bronze Age | Ulmus/Celtis sp. | C | <1% | [132] |

| 86 | El Carrizal de Cuéllar | Lastras de Cuéllar, Spain | 4576–4346 cal BP | Celtis sp. | P | <10% | [133] |

3.2. New Direct Radiocarbon Dating of Celtis Remains

3.3. Chemical Composition of Celtis australis Fruits

4. Discussion

4.1. All That Is Uncharred Is Not Intrusive

4.2. Variation in the Geographic Distribution of Celtis spp.

4.3. Gathered during the Palaeolithic

5. Conclusions

- Celtis sp. is present in archaeological contexts even in ancient chronologies and despite its (usually) uncharred state. The dating of the remains of Abrigo de la Quebrada and Cueva del Arco joins that of Douara cave and confirms their antiquity, so we must not systematically doubt the uncharred remains.

- Celtis australis seems to be adapted to Mediterranean droughts but sensitive to cold periods, such as MIS 10 or MIS2, founding refugia, firstly in the Mediterranean Basin, and secondly being reduced in the Near East.

- During the Lower Pleistocene and the Middle Holocene, the distribution of Celtis populations matches up with their current distribution, whereas during the Middle Pleistocene, they exceed their current limits, reaching northern Europe, which is related to climatic phases that are more favourable to their spread.

- Its scarce presence in the southern peninsulas of Europe, traditionally considered refugia, during the Final Upper Pleistocene and Lower Holocene is noteworthy, but we cannot rule out that this is due to bias in the sampling or in data publication.

- The hypothesis of human gathering of Celtis fruits is based on (1) the absence of charred hackberry wood, perhaps linked to some vegetation management, which protects the foodstuffs, and (2) their high protein and carbohydrates input related to the presence of sucrose, glucose and fructose fits within a diet, which includes different types of resources, as documented in several Palaeolithic sites.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrón, E.; Rivas-Carballo, R.; Postigo-Mijarra, J.M.; Alcalde-Olivares, C.; Vieira, M.; Castro, L.; Pais, J.; Valle-Hernández, M. The Cenozoic Vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula: A Synthesis. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2010, 162, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suc, J.-P. Origin and Evolution of the Mediterranean Vegetation and Climate in Europe. Nature 1984, 307, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suc, J.-P.; Zagwijn, W.H. Plio-Pleistocene Correlations between the Northwestern Mediterranean Region and Northwestern Europe According to Recent Biostratigraphic and Palaeoclimatic Data. Boreas 1983, 12, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauquette, S.; Quézel, P.; Guiot, J.; Suc, J.-P. Signification bioclimatiquede taxons-guides du Pliocène méditerranéen. Geobios 1998, 31, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, E.; Roiron, P. La prehistoria de la vegetación en la Península Ibérica. Saguntum Pap. Lab. Arqueol. Valencia 1995, 28, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Postigo Mijarra, J.M.; Gómez Manzaneque, F.; Morla, C. Survival and Long-Term Maintenance of Tertiary Trees in the Iberian Peninsula during the Pleistocene: First Record of Aesculus L. (Hippocastanaceae) in Spain. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2008, 17, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altolaguirre, Y.; Schulz, M.; Gibert, L.; Bruch, A.A. Mapping Early Pleistocene Environments and the Availability of Plant Food as a Potential Driver of Early Homo Presence in the Guadix-Baza Basin (Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 2021, 155, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altolaguirre, Y.; Bruch, A.A.; Gibert, L. A Long Early Pleistocene Pollen Record from Baza Basin (SE Spain): Major Contributions to the Palaeoclimate and Palaeovegetation of Southern Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 231, 106199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, J.J.; Rubio-Cuadrado, Á. Relating Climate, Drought and Radial Growth in Broadleaf Mediterranean Tree and Shrub Species: A New Approach to Quantify Climate-Growth Relationships. Forests 2020, 11, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plants of the World Online (POWO). Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- World Flora Online. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org/ (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Euro+Med PlantBase. Available online: https://europlusmed.org/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Navarro Aranda, C.; Castroviejo, S. Celtis L. In Flora Ibérica; Castroviejo, S., Aedo, C., Laínz, M., Muñoz Garmendia, F., Nieto Feliner, G., Paiva, J., Benedí, C., Eds.; Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1993; Volume 3, pp. 248–250. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Aceituno, L.; Molina, M. (Eds.) Inventario Español de los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a la Biodiversidad. Fase I: Introducción, Metodología y Fichas; Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, Secretaría General Técnica: Madrid, Spain, 2014; ISBN 978-84-491-1401-4.

- Magni, D.; Caudullo, G. Celtis australis in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxemburgo, 2016; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.; Obón, C. La guía de Incafo de las Plantas Útiles y Venenosas de la Península Ibérica y Baleares (Excluidas Medicinales); Incafo: Madrid, Spain, 1991; ISBN 978-84-85389-83-4. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Díez, P.; Montserrat-Martí, G.; Cornelissen, J.H.C. Trade-Offs between Phenology, Relative Growth Rate, Life Form and Seed Mass among 22 Mediterranean Woody Species. Plant Ecol. 2003, 166, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, M.A.; Arizpe, D. Manual de Propagación de Árboles y Arbustos de Ribera: Una Ayuda para la Restauración de Riberas en la Región Mediterránea; Conselleria de Medi Ambient, Aigua, Urbanisme i Habitatge: València, Spain, 2008; ISBN 978-84-482-4964-9. [Google Scholar]

- Piera, H. Plantas Silvestres y Setas Comestibles del Valle de Ayora Cofrentes; Grupo Acción Local Valle Ayora-Cofrentes: Ayora (Valencia), Spain, 2006; ISBN 978-84-611-3162-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer, J. Costumari Botànic: Recerques Etnobotàniques a Les Comarques Centrals Valencianes (1), 2nd ed.; Farga Monogràfica; Edicions del Bullent: Picanya, Spain, 2000; ISBN 978-84-96187-13-9. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Varea, C.M.; Badal, E.; Carrión Marco, Y. A La Sombra Del Almez. In Usos Artesanos e Industriales de las Plantas en la Comunitat Valenciana; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2021; pp. 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión Marco, Y.; Pérez Jordà, G. Análisis de Restos Vegetales. In ḥiṣn Turīš. Castell de Turís. El Castellet: 500 años de historia; Jiménez Salvador, J.L., Díes Cusí, E., Tierno Richart, J., Eds.; Saguntum Extra: Valencia, Sapin, 2014; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lieutaghi, P. Le Livre des Arbres, Arbustes & Arbrisseaux, 2nd ed.; Actes Sud: Arles, France, 2004; ISBN 978-2-7427-4778-8. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Kumar, M.; Cabral-Pinto, M.M.S.; Bhatt, B.P. Seasonal and Altitudinal Variation in Chemical Composition of Celtis australis L. Tree Foliage. Land 2022, 11, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada Soler, M. Estudi Etnobotànic de la Comarca de l’Alt Empordà; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/2621 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Font Quer, P. Plantas Medicinales: El Dioscórides Renovado; Península: Barcelona, Spain, 1999; ISBN 978-84-8307-242-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Morales, R. Ethnobotanical Review of Wild Edible Plants in Spain. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2006, 152, 27–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plants for a Future: Earth, Plants, People. Available online: https://pfaf.org (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Figueiral, I.; Ivorra, S.; Breuil, J.-Y.; Bel, V.; Houix, B. Gallo-Roman Nîmes (Southern France): A Case Study on Firewood Supplies for Urban and Proto-Urban Centers (1st B.C.–3rd A.D.). Quat. Int. 2017, 458, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabaza Bravo, J.M.; García Sánchez, E.; Hernández Bermejo, J.E.; Jiménez, A. Árboles y Arbustos en Al-Andalus; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, Spain, 2004; ISBN 978-84-00-08273-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jahren, A.H.; Amundson, R. Potential for 14C Dating of Biogenic Carbonate in Hackberry (Celtis) Endocarps. Quat. Res. 1997, 47, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beta Analytic Standard Pretreatment Protocols: Acid Etch. Available online: https://www.radiocarbon.com/pretreatment-carbon-dating.htm#Etch (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Simchoni, O.; Kislev, M.E. Early Finds of Celtis Australis in the Southern Levant. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2011, 20, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahren, A.H.; Gabel, M.L.; Amundson, R. Biomineralization in Seeds: Developmental Trends in Isotopic Signatures of Hackberry. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1998, 138, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messager, E.; Badou, A.; Fröhlich, F.; Deniaux, B.; Lordkipanidze, D.; Voinchet, P. Fruit and Seed Biomineralization and Its Effect on Preservation. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2010, 2, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillito, L.-M.; Almond, M.J.; Nicholson, J.; Pantos, M.; Matthews, W. Rapid Characterisation of Archaeological Midden Components Using FT-IR Spectroscopy, SEM–EDX and Micro-XRD. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2009, 73, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.; Dove, P.M. An Overview of Biomineralization Processes and the Problem of the Vital Effect. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003, 54, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovsky, E.; Nelson, E.K.; Kingsbury, R.M. Berries Rich in Calcium. Science 1952, 75, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweingruber, F.H. Anatomie Europäischer Hölzer; Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsenin, N.N. Physical Properties of Plants and Animal Materials: Structure, Physical Characteristics and Mechanical Properties; Gordon and Breach Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-1-00-306232-5. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Method of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists International, 18th ed.; AOAC: Arlington, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arnous, A.; Makris, D.P.; Kefalas, P. Correlation of Pigment and Flavanol Content with Antioxidant Properties in Selected Aged Regional Wines from Greece. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2002, 15, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamarev, E. Paleobotanical Evidences of the Tertiary History and Origin of the Mediterranean Sclerophyll Dendroflora. Plant Syst. Evol. 1989, 162, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allué, E.; Cáceres, I.; Expósito, I.; Canals, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Rosell, J.; Bermúdez de Castro, J.M.; Carbonell, E. Celtis Remains from the Lower Pleistocene of Gran Dolina, Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 53, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messager, E.; Lordkipanidze, D.; Ferring, C.R.; Deniaux, B. Fossil Fruit Identification by SEM Investigations, a Tool for Palaeoenvironmental Reconstruction of Dmanisi Site, Georgia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 2715–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INPN-Inventaires Archéozoologiques et Archéobotaniques de France (I2AF). Available online: https://inpn.mnhn.fr/espece/jeudonnees/3471 (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Girard, V.; Fauquette, S.; Adroit, B.; Suc, J.-P.; Leroy, S.A.G.; Ahmed, A.; Paya, A.; Ali, A.A.; Paradis, L.; Roiron, P. Fossil Mega- and Micro-Flora from Bernasso (Early Pleistocene, Southern France): A Multimethod Comparative Approach for Paleoclimatic Reconstruction. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2019, 267, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, S.A.G.; Roiron, P. Latest Pliocene Pollen and Leaf Floras from Bernasso Palaeolake (Escandorgue Massif, Hérault, France). Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 1996, 94, 295–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suc, J.-P. Analyse Pollinique de Dépôts Plio-Pléistocènes Du Sud Du Massif Basaltique de l’Escandorgue (Site de Bernasso, Lunas, Hérault, France). Pollen Spores 1978, 20, 497–512. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, S.A.G. Climatic and Non-Climatic Lake-Level Changes Inferred from a Plio-Pleistocene Lacustrine Complex of Catalonia (Spain): Palynology of the Tres Pins Sequences. J. Paleolimnol. 1997, 17, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, F. Vegetation Response to Early Pleistocene Climatic Cycles in the Lamone Valley (Northern Apennines, Italy). Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2007, 145, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravazzi, C.; Strick, M.R. Vegetation Change in a Climatic Cycle of Early Pleistocene Age in the Leffe Basin (Northern Italy). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1995, 117, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, S.; Ambert, P.; Suc, J.-P. Pollen Record of the Saint-Macaire Maar (Hérault, Southern France): A Lower Pleistocene Glacial Phase in the Languedoc Coastal Plain. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 1994, 80, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo Mijarra, J.M.; Burjachs, F.; Gómez Manzaneque, F.; Morla, C. A Palaeoecological Interpretation of the Lower–Middle Pleistocene Cal Guardiola Site (Terrassa, Barcelona, NE Spain) from the Comparative Study of Wood and Pollen Samples. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2007, 146, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault-Miskovsky, J.; Girard, M. Analyse pollinique du remplissage pleistocène inférieur et moyen de la grotte du Vallonnet (Roquebrune—Cap-Martin, Alpe-Maritimes). Géologie Méditerranéenne 1978, 5, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Burjachs, F.; Cuenca-Bescós, G.; García, N.; Van der Made, J.; Pérez González, A.; Blain, H.-A.; Expósito, I.; López-García, J.M.; García Antón, M.; et al. One Million Years of Cultural Evolution in a Stable Environment at Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2011, 30, 1396–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittmann, F. The Kärlich Interglacial, Middle Rhine Region, Germany: Vegetation History and Stratigraphic Position. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 1992, 1, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifay, E. Grotte de l’Escale. In Provence et Languedoc Mediterranéen sites Paléolithiques et Néolithiques, Proceedings of the Livret-Guide de l’excursion C 2, IXe Congrès Union Internationale des Sciences Préhistoriques et Protohistoriques, Nice, France, 13–18 Septembre 1976; De Lumley, H., Ed.; Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: Paris, France, 1976; pp. 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Leroi-Gourhan, A. L’homme et Le Mileu Végétal (Chapitre II). In Approche Ecologique de l’Homme Fossile; Laville, H., Renault-Miskovsky, J., Eds.; Supplément au Bulletin de l’Association Française Pour l’Etude du Quaternaire; Université Pierre et Marie Curie: Paris, France, 1977; pp. 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Renault-Miskovsky, J.; de Beaulieu, J.-L.; Vernet, J.-L.; Behre, K.-E.; Lartigot, A.S. Études Palynologique, Anthracologique et Des Macrorestes Végétaux Des Formations Pliocènes et Pleistocènes Du Site de Terra Amata. In Terra Amata. Nice, Alpes-Maritimes, France. Tome II: Palynologie, Anthracologie, Faunes, Mollusques, Paléoenvironnements, Paléoanthropologie; De Lumley, H., Ed.; CNRS Editions: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Peris, J.; Guillem Calatayud, P.M.; Martínez Valle, R. Cova Del Bolomor (Tavernes de La Valldigna, Valencia). Datos Cronoestratigráficos y Culturales de Una Secuencia Del Pleistoceno Medio. In Proceedings of the Paleolítico da Península Ibérica. Actas do 3o Congresso de Arqueologia Peninsular, Vila Real, Portugal, 21–27 September 1999; ADECAP: Porto, Portugal, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pidek, I.A.; Poska, A. Pollen Based Quantitative Climate Reconstructions from the Middle Pleistocene Sequences in Łuków and Zdany (E Poland): Species and Modern Analogues Based Approach. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2013, 192, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubin, V.P.; Bosinski, G. The Earliest Occupation of the Caucasus Region. In The Earliest Occupation of Europe: Proceedings of the European Science Foundation Workshop at Tautavel (France); Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia; Leiden University Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 207–253. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Antón, M.; Sainz-Ollero, H. Pollen Records from the Middle Pleistocene Atapuerca Site (Burgos, Spain). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1991, 85, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ber, A.; Janczyk-kopikowa, Z.; Krzyszkowski, D. A New Interglacial Stage in Poland (Augustovian) and the Problem of the Age of the Oldest Pleistocene Till. Quat. Sci. Rev. 1998, 17, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifay, E. Grottes Du Mas Des Caves. In Provence et Languedoc Mediterranéen sites Paléolithiques et Néolithiques, Proceedings of the Livret-Guide de l’excursion C 2, IXe Congrès Union Internationale des Sciences Préhistoriques et Protohistoriques, Nice, France, 13–18 Septembre 1976; De Lumley, H., Ed.; Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: Paris, France, 1976; pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Margari, V.; Roucoux, K.; Magri, D.; Manzi, G.; Tzedakis, P.C. The MIS 13 Interglacial at Ceprano, Italy, in the Context of Middle Pleistocene Vegetation Changes in Southern Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2018, 199, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyszkowski, D. An Outline of the Pleistocene Stratigraphy of the Kleszczów Graben, Bec̵hatów Outcrop, Central Poland. Quat. Sci. Rev. 1995, 14, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B. Biostratigraphic Correlation of the Kärlich Interglacial, Northwestern Germany. Boreas 1983, 12, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M. Palynologie Und Sedimentologie Der Interglazialprofile Döttingen, Bonstorf, Munster Und Bilshausen. Ph.D. Thesis, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Mainz, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsodendris, A.; Müller, U.C.; Pross, J.; Brauer, A.; Kotthoff, U.; Lotter, A.F. Vegetation Dynamics and Climate Variability during the Holsteinian Interglacial Based on a Pollen Record from Dethlingen (Northern Germany). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2010, 29, 3298–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissmann, L. Quaternary Geology of Eastern Germany (Saxony, Saxon–Anhalt, South Brandenburg, Thüringia), Type Area of the Elsterian and Saalian Stages in Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2002, 21, 1275–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ham, R.W.J.M.; Kuijper, W.J.; Kortselius, M.J.H.; van der Burgh, J.; Stone, G.N.; Brewer, J.G. Plant Remains from the Kreftenheye Formation (Eemian) at Raalte, The Netherlands. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2008, 17, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limondin-Lozouet, N.; Antoine, P.; Auguste, P.; Bahain, J.-J.; Carbonel, P.; Chaussé, C.; Connet, N.; Dupéron, J.; Dupéron, M.; Falguères, C.; et al. Le Tuf Calcaire de La Celle-Sur-Seine (Seine et Marne): Nouvelles Données Sur Un Site Clé Du Stade 11 Dans Le Nord de La France. Quaternaire 2006, 17, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernet, J.-L.; Mercier, N.; Bazile, F.; Brugal, J.-P. Travertins et terrasses de la moyenne vallée du Tarn à Millau (Sud du Massif Central, Aveyron, France): Datations OSL, contribution à la chronologie et aux paléoenvironnements. Quaternaire. Rev. De L’association Française Pour L’étude Du Quat. 2008, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saporta, G. de (1823–1895) A. In La Flore des Tufs Quaternaires en Provence ([Reprod.])/Par le Cte G. de Saporta; impr. A. Quantin: Paris, France, 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Roiron, P.; Chabal, L.; Figueiral, I.; Terral, J.-F.; Ali, A.A. Palaeobiogeography of Pinus Nigra Arn. Subsp. Salzmannii (Dunal) Franco in the North-Western Mediterranean Basin: A Review Based on Macroremains. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2013, 194, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuera, J.; Jiménez-Moreno, G.; Ramos-Román, M.J.; García-Alix, A.; Toney, J.L.; Anderson, R.S.; Jiménez-Espejo, F.; Bright, J.; Webster, C.; Yanes, Y.; et al. Vegetation and Climate Changes during the Last Two Glacial-Interglacial Cycles in the Western Mediterranean: A New Long Pollen Record from Padul (Southern Iberian Peninsula). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 205, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Marco, Y.; Guillem Calatayud, P.; Eixea, A.; Martínez-Varea, C.M.; Tormo, C.; Badal, E.; Zilhão, J.; Villaverde, V. Climate, Environment and Human Behaviour in the Middle Palaeolithic of Abrigo de La Quebrada (Valencia, Spain): The Evidence from Charred Plant and Micromammal Remains. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 217, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsutani, A. Plant Remains from the 1984 Excavations at Douara Cave. In Paleolithic Site of Douara Cave and Paleogeography of Palmyra Basin in Syria. Part IV: 1984 Excavation; Akazawa, T., Sakaguchi, Eds.; University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1987; pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kotzamani, G. From Gathering to Cultivation: Archaeobotanical Research on the Early Plant Exploitation and the Beginning of Agriculture in Greece (Theopetra, Schisto, Sidari, Dervenia). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ochando, J.; Carrión, J.S.; Blasco, R.; Fernández, S.; Amorós, G.; Munuera, M.; Sañudo, P.; Fernández Peris, J. Silvicolous Neanderthals in the Far West: The Mid-Pleistocene Palaeoecological Sequence of Bolomor Cave (Valencia, Spain). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 217, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando, J.; Carrión, J.S.; Blasco, R.; Rivals, F.; Rufà, A.; Amorós, G.; Munuera, M.; Fernández, S.; Rosell, J. The Late Quaternary Pollen Sequence of Toll Cave, a Palaeontological Site with Evidence of Human Activities in Northeastern Spain. Quat. Int. 2020, 554, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinoli, D. Food Plant Use, Temporal Changes and Site Seasonality at Epipalaeolithic Öküzini and Karain B Caves, Southwest Anatolia, Turkey. Paléorient 2004, 30, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyari, E.K.; Chapman, J.C.; Gaydarska, B.; Marinova, E.; Deli, T.; Huntley, J.P.; Allen, J.R.M.; Huntley, B. The ‘Oriental’ Component of the Balkan Flora: Evidence of Presence on the Thracian Plain during the Weichselian Late-Glacial. J. Biogeogr. 2008, 35, 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsartsidou, G.; Karkanas, P.; Marshall, G.; Kyparissi-Apostolika, N. Palaeoenvironmental Reconstruction and Flora Exploitation at the Palaeolithic Cave of Theopetra, Central Greece: The Evidence from Phytolith Analysis. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2015, 7, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinopoli, G.; Masi, A.; Regattieri, E.; Wagner, B.; Francke, A.; Peyron, O.; Sadori, L. Palynology of the Last Interglacial Complex at Lake Ohrid: Palaeoenvironmental and Palaeoclimatic Inferences. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2018, 180, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambert, P.; Quinif, Y.; Roiron, P.; Arthuis, R. Les travertins de la vallee du Lez (Montpellier, Sud de la France). Datations 230Th/234U et environnements pleistocenes. Comptes Rendus-Acad. Des Sci. Ser. II Sci. Terre Planetes 1995, 321, 667–674. [Google Scholar]

- Planchon, G. Étude des Tufs de Montpellier au Point de vue Géologique et Paléontologique; Hachette Livre BNF: Paris, France, 1864. [Google Scholar]

- Akazawa, T. The Ecology of the Middle Paleolithic Occupation at Douara Cave, Syria. Anthropologie 1987, 92, 883–900. [Google Scholar]

- Mclaren, F.S. Plums from Douara Cave, Syria: The Chemical Analysis of Charred Stone Fruits. In Proceedings of the Res Archaebotanicae, 9th Symposium IWPG, Kiel, Germany, 16–24 May 1992; Kroll, H., Pasternak, R., Eds.; Oetker-Voges: Kiel, Germany, 1995; pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Mallol, C.; Hernández, C.M.; Cabanes, D.; Sistiaga, A.; Machado, J.; Rodríguez, Á.; Pérez, L.; Galván, B. The Black Layer of Middle Palaeolithic Combustion Structures. Interpretation and Archaeostratigraphic Implications. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 2515–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Matutano, P.; Pérez-Jordà, G.; Hernández, C.M.; Galván, B. Macrobotanical Evidence (Wood Charcoal and Seeds) from the Middle Palaeolithic Site of El Salt, Eastern Iberia: Palaeoenvironmental Data and Plant Resources Catchment Areas. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 19, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Moreno, A.; Rios Garaizar, J.; Marín Arroyo, A.B.; Eugenio Ortíz, J.; De Torres, T.; López-Dóriga, I. La Secuencia Musteriense de La Cueva Del Niño (Aýna, Albacete) y El Poblamiento Neandertal En El Sureste de La Península Ibérica. Trab. Prehist. 2014, 71, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckers, K.; Riehl, S.; Jenkins, E.; Rosen, A.; Dodonov, A.; Simakova, A.N.; Conard, N.J. Vegetation Development and Human Occupation in the Damascus Region of Southwestern Syria from the Late Pleistocene to Holocene. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2009, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, S.E.; Ross, S.A.; Sobotkova, A.; Herries, A.I.R.; Mooney, S.D.; Longford, C.; Iliev, I. Environmental Conditions in the SE Balkans since the Last Glacial Maximum and Their Influence on the Spread of Agriculture into Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013, 68, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando, J.; Carrión, J.S.; Blasco, R.; Rivals, F.; Rufà, A.; Demuro, M.; Arnold, L.J.; Amorós, G.; Munuera, M.; Fernández, S.; et al. Neanderthals in a Highly Diverse, Mediterranean-Eurosiberian Forest Ecotone: The Pleistocene Pollen Record of Teixoneres Cave, Northeastern Spain. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 241, 106429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabukcu, C. Woodland Vegetation History and Human Impacts in South-Central Anatolia 16,000–6500 Cal BP: Anthracological Results from Five Prehistoric Sites in the Konya Plain. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2017, 176, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colledge, S.; Conolly, J. Reassessing the Evidence for the Cultivation of Wild Crops during the Younger Dryas at Tell Abu Hureyra, Syria. Environ. Archaeol. 2010, 15, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.M.; Hillman, G.C.; Legge, A.J. The Excavation of Tell Abu Hureyra in Syria: A Preliminary Report. Proc. Soc. 1975, 41, 50–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössner, C.; Deckers, K.; Benz, M.; Özkaya, V.; Riehl, S. Subsistence Strategies and Vegetation Development at Aceramic Neolithic Körtik Tepe, Southeastern Anatolia, Turkey. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2018, 27, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Bertini, A.; Capezzuoli, E.; Horvatinčić, N.; Andrews, J.E.; Fauquette, S.; Fedi, M. Palynological Investigation of a Late Quaternary Calcareous Tufa and Travertine Deposit: The Case Study of Bagnoli in the Valdelsa Basin (Tuscany, Central Italy). Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2015, 218, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, G. Timber and Trees: Ancient Exploitation in the Middle East: Evidence from Plant Remains. Bull. Sumer. Agric. 1992, 6, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- van Zeist, W.; Roller, G.J. de The Plant Husbandry of Aceramic Çayönü, SE Turkey. Palaeohistoria 1994, 33–34, 65–96. Available online: https://ugp.rug.nl/Palaeohistoria/article/view/25060 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Helbaek, H. The Plant Husbandry of Hacilar. In Excavations at Hacilar; Mellaart, J., Ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, Scotland, 1970; Volume 1, pp. 189–244. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher-Schneider, R.; de Beaulieu, J.-L.; Magny, M.; Walter-Simonnet, A.-V.; Bossuet, G.; Millet, L.; Brugiapaglia, E.; Drescher, A. Vegetation History, Climate and Human Impact over the Last 15,000 Years at Lago Dell’Accesa (Tuscany, Central Italy). Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2007, 16, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinner, W.; van Leeuwen, J.F.N.; Colombaroli, D.; Vescovi, E.; van der Knaap, W.O.; Henne, P.D.; Pasta, S.; D’Angelo, S.; La Mantia, T. Holocene Environmental and Climatic Changes at Gorgo Basso, a Coastal Lake in Southern Sicily, Italy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2009, 28, 1498–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, G.; Fornite, S.; Herveux, L. Early Holocene Cultivation before Domestication in Northern Syria. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2008, 17, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilaine, J.; Briois, F.; Vigne, J.-D.; Carrère, I.; Chazelles-Gazzal, C.-A.; de Collonge, J.; Gazzal, H.; Gérard, P.; Haye, L.; Manen, C.; et al. L’habitat néolithique pré-céramique de Shillourokambos (Parekklisha, Chypre). Bull. Corresp. Hellénique 2002, 126, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigne, J.-D.; Briois, F.; Cucchi, T.; Franel, Y.; Mylona, P.; Tengberg, M.; Touquet, R.; Wattez, J.; Willcox, G.; Zazzo, A. Klimonas, a Late PPNA Hunter-Cultivator Village in Cyprus: New Results. Nouv. Données Débuts Néolithique À Chypr. 2015, 9, 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, R. Investigations of Botanical Remains from Nevali Cori PPNB, Turkey: A Short Interim Report. In Origin of Agricultural and Crop Domestication; Damania, A.B., Valkoum, J., Willcox, G., Quallset, C.O., Eds.; ICARDA: Aleppo, Syria, 1998; pp. 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- van Zeist, W.; de Roller, G.J. Plant Remains from Asikli Höyük, a Pre-Pottery Neolithic Site in Central Anatolia. Veget. Hist. Archaebot. 1995, 4, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zeist, W.; van Smith, P.E.L.; Palfenier-Vegter, R.M.; Suwijn, M.; Casparie, W.A. An Archaeobotanical Study of Ganj Dareh Tepe, Iran. Palaeohistoria 1984, 26, 201–224. [Google Scholar]

- Jahns, S. The Holocene History of Vegetation and Settlement at the Coastal Site of Lake Voulkaria in Acarnania, Western Greece. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2005, 14, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpaki, A. Archaeobotanical Seed Remains. In The Cave of the Cyclops: Mesolithic and Neolithic Networks in the Northern Aegean, Greece: Volume I: Intra-Site Analysis, Local Industries, and Regional Site Distribution; Prehistory Monographs; INSTAP: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- French, D.H.; Hillman, G.C.; Payne, S. Excavations at Can Hasan III. In Papers in Economic Prehistory; Higgs, E.S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1972; pp. 182–188. [Google Scholar]

- Willcox, G. Exploitation des espèces ligneuses au Proche-Orient: Données anthracologiques. Paléorient 1991, 17, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn, A.; Asouti, E.; Near, J.; Martinoli, D. Macro-Botanical Evidence for Plant Use at Neolithic Çatalhöyük South-Central Anatolia, Turkey. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2002, 11, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moulins, M.-D.F.J. Agricultural Changes at Euphrates and Steppe Sites in the Mid-8th to the 6th Millennium B.C. Ph.D. Thesis, University of London, London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.M. Khirokitia Plant Remains: Preliminary Report. In Fouilles Récentes à Khirokitia (Chypre), 1983–1986; Le Brun, A., Ed.; Etudes Néolithiques; Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations: Paris, France, 1989; pp. 393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.A. The Plant Remains. In The Colonosation and Settlement of Cyprus. Investigations at Kissonerga-Mylouthkia, 1976–1996; Peltenburg, E., Ed.; Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology; Paul Aströms Förlag: Sävedalen, Sweden, 2003; Volume 4, pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.T. Paleobotanic Investigation: 1972 Season. Bull. Am. Sch. Orient. Research. Suppl. Stud. 1974, 18, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, L.M. Economy and Interaction: Exploring Archaeobotanical Contributions in Prehistoric Cyprus. Ph.D. Thesis, University Colledge of London, London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- López-Dóriga, I. The Use of Plants during the Mesolithic and the Neolithic in the Atlantic Coast of the Iberian Peninsula. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Cantabria, Santander, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Asouti, E. Woodland Vegetation and Fuel Exploitation at the Prehistoric Campsite of Pınarbaşı, South-Central Anatolia, Turkey: The Evidence from the Wood Charcoal Macro-Remains. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2003, 30, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zeist, W.; Bakker-Heeres, J.A.H. Archaeobotanical Studies in the Levant: I. Neolithic Sites in the Damascus Basin: Aswad, Ghoraife, Ramad. Palaeohistoria 1982, 24, 165–256. [Google Scholar]

- Hovsepyan, R.; Willcox, G. The Earliest Finds of Cultivated Plants in Armenia: Evidence from Charred Remains and Crop Processing Residues in Pisé from the Neolithic Settlements of Aratashen and Aknashen. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2008, 17, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehl, S.; Marinova, E. Mid-Holocene Vegetation Change in the Troad (W Anatolia): Man-Made or Natural? Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2008, 17, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozilova, E.; Beug, H.-J. Studies on the Vegetation History of Lake Varna Region, Northern Black Sea Coastal Area of Bulgaria. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 1994, 3, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.A. Archaeobotanical Report. In Lemba Archaeological Report Volume II.1B: Excavations at Kissonerga-Mosphilia, 1979–1992; Peltenburg, E., Ed.; University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, Scotland, 1998; pp. 317–338. [Google Scholar]

- Mavromati, A. Uses of Wood and Tree Management in the Bronze Age Aegean (Greece). The Cases of Akrotiri on Thera and Heraion on Samos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de València, València, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Múgica, F.; García-Antón, M.; Maldonado-Ruiz, J.; Morla-Juaristi, C.; Sainz-Ollero, H. Ancient Pine Forest on Inland Dunes in the Spanish Northern Meseta. Quat. Res. 2005, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radiocarbon Dating. Available online: https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/radiocarbon-dating.html (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Miami, B.A. 4985 S.W. 74th C. What Is Carbon-14 (14C) Dating? Carbon Dating Definition. Available online: https://www.radiocarbon.com/about-carbon-dating.htm (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Kobayashi, K.; Yoshida, K.; Nagai, H.; Imamura, M.; Yoshikawa, H.; Yamashita, H.; Ohizaki, S.; Yagi, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Honda, M. 14C Dating by Accelerator Mass Spectrometry of Carbonized Plant Remains from a Middle Paleolithic Hearth at Douara Cave, Syria. In Paleolithic Site of Douara Cave and Paleogeography of Palmyra Basin in Syria. Part IV: 1984 Excavation; University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1987; p. 147. ISBN 0910-481X. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Cascales, E.; Prencipe, D.; Nocentini, C.; López Sánchez, R.; Ros García, J.M. Characteristics and Composition of Hackberries (Celtis australis L.) from Mediterranean Forests. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2021, 33, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demır, F.; Doğan, H.; Özcan, M.; Haciseferoğullari, H. Nutritional and Physical Properties of Hackberry (Celtis australis L.). J. Food Eng. 2002, 54, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudraa, S.; Hambaba, L.; Zidani, S.; Boudraa, H. Composition Minérale et Vitaminique Des Fruits de Cinq Espèces Sous Exploitées En Algérie: Celtis australis L., Crataegus azarolus L., Crataegus monogyna Jacq., Elaeagnus angustifolia L. et Zizyphus lotus L. Fruits 2010, 65, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, A.; Višnjevec, A.M.; Vidrih, R.; Prgomet, Ž.; Nečemer, M.; Hribar, J.; Cimerman, N.G.; Možina, S.S.; Bučar-Miklavčič, M.; Ulrih, N.P. Nutritional, Antioxidative, and Antimicrobial Analysis of the Mediterranean Hackberry (Celtis australis L.). Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, M.C.; Sichieri, R.; Venturim Mozzer, R. A Low-Energy-Dense Diet Adding Fruit Reduces Weight and Energy Intake in Women. Appetite 2008, 51, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Data Central (FDC); United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service. Available online: https://www.fdc.nal.usda.gov (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Bhatt, I.D.; Rawat, S.; Badhani, A.; Rawal, R.S. Nutraceutical Potential of Selected Wild Edible Fruits of the Indian Himalayan Region. Food Chem. 2017, 215, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filali-Ansari, N.; El Abbouyi, A.; Kijjoa, A.; El Maliki, S.; El Khyari, S. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Chemical Constituents from Celtis Australis. Der Pharma Chem. 2016, 8, 338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, N.F. The Use of Plants at Anau North. In A Central Asian Village at the Dawn of Civilization, Excavations at Anau, Turkmenistan; Hiebert, F.T., Ed.; University Museum Monograph; University of Pennsylvania Museum: Philadephia, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zeist, W.; Waterbolk-Van-Rooijen, W. The Palaeobotany of Tell Bouqras, Eastern Syria. Paléorient 1985, 11, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzavzez, J.; Théry-Parisot, I.; Fiorucci, G.; Terral, J.-F.; Thibaut, B. Impact of Post-Depositional Processes on Charcoal Fragmentation and Archaeobotanical Implications: Experimental Approach Combining Charcoal Analysis and Biomechanics. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 44, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Varea, C.M.; Carrión Marco, Y.; Badal, E. Preservation and Decay of Plant Remains in Two Palaeolithic Sites: Abrigo de La Quebrada and Cova de Les Cendres (Eastern Spain). What Information Can Be Derived? J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 29, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Matutano, P.; Hernández, C.M.; Galván, B.; Mallol, C. Neanderthal Firewood Management: Evidence from Stratigraphic Unit IV of Abric Del Pastor (Eastern Iberia). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2015, 111, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, E. El interés económico del pino piñonero para los habitantes de la Cueva de Nerja. In Las Culturas del Pleistoceno Superior en Andalucía; Patronato de la Cueva de Nerja: Málaga, Spain, 1998; pp. 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Zilhão, J.; Angelucci, D.E.; Igreja, M.A.; Arnold, L.J.; Badal, E.; Callapez, P.; Cardoso, J.L.; d’Errico, F.; Daura, J.; Demuro, M.; et al. Last Interglacial Iberian Neandertals as Fisher-Hunter-Gatherers. Science 2020, 367, eaaz7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Varea, C.M.; Ferrer-Gallego, P.P.; Raigón, M.D.; Badal, E.; Ferrando-Pardo, I.; Laguna, E.; Real, C.; Roman, D.; Villaverde, V. Corema Album Archaeobotanical Remains in Western Mediterranean Basin. Assessing Fruit Consumption during Upper Palaeolithic in Cova de Les Cendres (Alicante, Spain). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 207, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Marco, Y.; Ntinou, M.; Badal, E. Olea europaea L. in the North Mediterranean Basin during the Pleniglacial and the Early–Middle Holocene. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2010, 29, 952–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahren, A.H.; Amundson, R.; Kendall, C.; Wigand, P. Paleoclimatic Reconstruction Using the Correlation in Δ18O of Hackberry Carbonate and Environmental Water, North America. Quat. Res. 2001, 56, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K.; Provan, J. What Do We Mean by ‘Refugia’? Quat. Sci. Rev. 2008, 27, 2449–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampe, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, F.; Dobrowski, S.; Hu, F.S.; Gavin, D.G. Climate Refugia: From the Last Glacial Maximum to the Twenty-First Century. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, R.J.; Aguinagalde, I.; de Beaulieu, J.-L.; Bittkau, C.; Brewer, S.; Cheddadi, R.; Ennos, R.; Fineschi, S.; Grivet, D.; Lascoux, M.; et al. Glacial Refugia: Hotspots But Not Melting Pots of Genetic Diversity. Science 2003, 300, 1563–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taberlet, P.; Fumagalli, L.; Wust-Saucy, A.-G.; Cosson, J.-F. Comparative Phylogeography and Postglacial Colonization Routes in Europe. Mol. Ecol. 1998, 7, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taberlet, P.; Cheddadi, R. Quaternary Refugia and Persistence of Biodiversity. Science 2002, 297, 2009–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hammen, T.; Wijmstra, T.A.; Zagwijn, W.H.; Turekian, K.K. The Floral Record of the Late Cenozoic of Europe. In The Late Cenozoic Glacial Ages; Turekian, K.K., Ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1971; pp. 391–424. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Ambrosiani, K.; Linde, B.B.; Miller, U.; Robertsson, A.-M.; Seiriene, V. Relocated Interglacial Lacustrine Sediments from an Esker at Snickarekullen, S.W. Sweden. Veget. Hist. Archaebot. 1998, 7, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, R.C.; Parfitt, S.A.; Bridgland, D.R.; Lewis, S.G.; Rowe, P.J.; Atkinson, T.C.; Candy, I.; Debenham, N.C.; Penkman, K.E.H.; Rhodes, E.J.; et al. Terrestrial Environments during MIS 11: Evidence from the Palaeolithic Site at West Stow, Suffolk, UK. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2007, 26, 1236–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.R.; Jouzel, J.; Raynaud, D.; Barkov, N.I.; Barnola, J.-M.; Basile, I.; Bender, M.; Chappellaz, J.; Davis, M.; Delaygue, G.; et al. Climate and Atmospheric History of the Past 420,000 Years from the Vostok Ice Core, Antarctica. Nature 1999, 399, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrynowiecka, A.; Stachowicz-Rybka, R.; Niska, M.; Moskal-del Hoyo, M.; Börner, A.; Rother, H. Eemian (MIS 5e) Climate Oscillations Based on Palaeobotanical Analysis from the Beckentin Profile (NE Germany). Quat. Int. 2021, 605–606, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidek, I.A.; Zalat, A.A.; Hrynowiecka, A.; Żarski, M. A High-Resolution Pollen and Diatom Record of Mid-to Late-Eemian at Kozłów (Central Poland) Reveals No Drastic Climate Changes in the Hornbeam Phase of This Interglacial. Quat. Int. 2021, 583, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, S.; Fuentes, N.; Carrión, J.S.; González-Sampériz, P.; Montoya, E.; Gil, G.; Vega-Toscano, G.; Riquelme, J.A. The Holocene and Upper Pleistocene Pollen Sequence of Carihuela Cave, Southern Spain. Geobios 2007, 40, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntinou, M.; Kyparissi-Apostolika, N. Local Vegetation Dynamics and Human Habitation from the Last Interglacial to the Early Holocene at Theopetra Cave, Central Greece: The Evidence from Wood Charcoal Analysis. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2016, 25, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, A.M.; Roucoux, K.H.; Collier, R.E.L.; Müller, U.C.; Pross, J.; Tzedakis, P.C. Vegetation Responses to Abrupt Climatic Changes during the Last Interglacial Complex (Marine Isotope Stage 5) at Tenaghi Philippon, NE Greece. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 154, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, G. The Genetic Legacy of the Quaternary Ice Ages. Nature 2000, 405, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, G.M. Some Genetic Consequences of Ice Ages, and Their Role in Divergence and Speciation. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1996, 58, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Orellana, L.; Ramil-Rego, P.; Muñoz Sobrino, C. The Response of Vegetation at the End of the Last Glacial Period (MIS 3 and MIS 2) in Littoral Areas of NW Iberia: Last Glacial Vegetation in Littoral Areas from NW Iberia. Boreas 2013, 42, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Sobrino, C.; Ramil-Rego, P.; Gómez-Orellana, L.; Díaz Varela, R. Palynological Data on Major Holocene Climatic Events in NW Iberia. Boreas 2005, 34, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramil-Rego, P.; Rodríguez-Guitián, M.; Muñoz-Sobrino, C. Sclerophyllous Vegetation Dynamics in the North of the Iberian Peninsula during the Last 16,000 Years. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. Lett. 1998, 7, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu-Andrés, I.; Ciurana, M.-J.; Aguilella, A.; Boisset, F.; Guara, M.; Laguna, E.; Currás, R.; Ferrer, P.; Vela, E.; Puche, M.F.; et al. Plastid DNA Homogeneity in Celtis australis L. (Cannabaceae) and Nerium oleander L. (Apocynaceae) throughout the Mediterranean Basin. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2015, 176, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxó, R. Étude Carpologique Des Puits de Lattes, Évaluation et Comparaison Avec l’habitat. Lattara 2005, 18, 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Borislavov, B. The Izvorovo Gold. A Bronze Age Tumulus from Harmanli District, Southeastern Bulgaria. Archaeol. Bulg. 2010, 1, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Popova, T. Plant Remains of Sanctuary and Necropolis. Interdiscip. Stud. 2018, 25, 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Brothwell, D.R.; Brothwell, P. Food in Antiquity: A Survey of the Diet of Early Peoples; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-8018-5740-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, R.W. The Occurrence of Endocarps of Celtis Barbouri At Choukoutien. Bull. Geol. Soc. China 1935, 14, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, K.; Bocherens, H.; Miller, J.B.; Copeland, L. Reconstructing Neanderthal Diet: The Case for Carbohydrates. J. Hum. Evol. 2022, 162, 103105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabukcu, C.; Hunt, C.; Hill, E.; Pomeroy, E.; Reynolds, T.; Barker, G.; Asouti, E. Cooking in Caves: Palaeolithic Carbonised Plant Food Remains from Franchthi and Shanidar. Antiquity 2022, 97, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, E.; Martínez-Varea, C.M. Cooked and Raw. Fruits and Seeds in the Iberian Palaeolithic. In Cooking with Plants in Ancient Europe and Beyond: Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Archaeology of Plant Foods; Valamoti, S.M., Dimoula, A., Ntinou, M., Eds.; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 201–218. ISBN 978-94-6427-035-8. [Google Scholar]

| Site | Laboratory Number | Analysed Material | Radiocarbon Age (BP) | Cal BP (95.4%) | Stable Isotopes | Percent Modern Carbon | D14C | ∆14C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrigo de la Quebrada | Beta–506374 | Carbonate | 35,120 ± 220 | 40,243–39,075 | IRMS δ13C: −9.3 o/oo IRMS δ18O: +6.1 o/oo | 1.26 ± 0.03 pMC | −987.37 ± 0.35 o/oo | −987.48 ± 0.35 o/oo (1950:2018) |

| Cueva del Arco | Beta–627630 | Carbonate | 31,190 ± 190 | 36,091–35,203 | IRMS δ13C: −6.5 o/oo IRMS δ18O: +9.0 o/oo | 2.06 ± 0.05 pMC | −979.41 ± 0.49 o/oo | −979.58 ± 0.49 o/oo (1950:2022) |

| Parameter | Value (Mean ± SD) | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit fruit weight (g) | 0.505 ± 0.051 | 0.400 | 0.587 |

| Fruit diameter (mm) | 9.20 ± 0.63 | 7.89 | 10.35 |

| Fruit height (mm) | 10.22 ± 0.84 | 8.49 | 11.67 |

| Fruit volume (mm3) | 1742.60 ± 326.99 | 1067.82 | 2425.30 |

| Geometric mean diameter (mm) | 9.31 ± 0.57 | 7.92 | 10.4 |

| Degree of sphericity | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 0.79 | 1.01 |

| Surface area (mm2) | 273.29 ± 33.34 | 196.86 | 339.56 |

| Pulp and peel weight (g) | 0.211 ± 0.005 | 0.207 | 0.217 |

| Seed weight (g) | 10.833 ± 0.472 | 10.200 | 11.300 |

| Pulp and peel (%) | 42.88 ± 0.48 | 42.35 | 43.50 |

| Seed (%) | 56.43 ± 0.23 | 56.12 | 56.67 |

| Parameter | Value (Mean ± SD) | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter (%) whole fruit | 81.60 ± 0.22 | 81.30 | 81.80 |

| Dry matter (%) pulp and peel | 76.44 ± 0.40 | 75.90 | 76.81 |

| Moisture (%) whole fruit | 18.40 ± 0.22 | 18.20 | 18.70 |

| Moisture (%) pulp and peel | 23.56 ± 0.40 | 23.19 | 24.10 |

| Fat (%) | 0.489 ± 0.052 | 0.449 | 0.561 |

| Protein (%) | 2.49 ± 0.02 | 2.45 | 2.51 |

| Ashes (%) | 4.035 ± 0.118 | 3.934 | 4.198 |

| Fibre (%) | 7.34 ± 0.21 | 7.18 | 7.62 |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 62.10 ± 0.27 | 61.73 | 62.32 |

| Energy (kcal 100 g−1) | 262.75 ± 0.56 | 13.849 | 15.064 |

| Parameter | Value (Mean ± SD) | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.55 ± 0.05 | 6.49 | 6.59 |

| Titratable acidity (g citric acid 100 g−1 fw) | 0.247 ± 0.029 | 0.210 | 0.280 |

| Soluble solids content (°Brix) | 48.67 ± 1.73 | 47.00 | 51.00 |

| Total polyphenols (mg EAG 100 g−1 fw) | 192.19 ± 12.60 | 174.85 | 203.03 |

| Total antioxidant capacity (μmol Trolox 100 g−1 fw) | 770.70 ± 97.85 | 650.43 | 885.92 |

| Parameter (mg 100 g−1 fw) | Value (Mean ± SD) | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium | 413.910 ± 1.020 | 412.550 | 414.940 |

| Potassium | 358.247 ± 1.822 | 356.35 | 360.65 |

| Calcium | 212.479 ± 1.148 | 211.601 | 214.073 |

| Phosphorus | 104.670 ± 0.022 | 104.640 | 104.690 |

| Sodium | 10.978 ± 0.493 | 10.353 | 11.534 |

| Boron | 3.687 ± 0.045 | 3.625 | 3.729 |

| Iron | 2.307 ± 0.108 | 2.188 | 2.447 |

| Copper | 0.479 ± 0.042 | 0.421 | 0.510 |

| Zinc | 0.203 ± 0.020 | 0.177 | 0.226 |

| Manganese | 0.144 ± 0.007 | 0.139 | 0.153 |

| Selenium | 0.143 ± 0.022 | 0.113 | 0.163 |

| Molybdenum | 0.013 ± 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Varea, C.M.; Carrión Marco, Y.; Raigón, M.D.; Badal, E. Redrawing the History of Celtis australis in the Mediterranean Basin under Pleistocene–Holocene Climate Shifts. Forests 2023, 14, 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14040779

Martínez-Varea CM, Carrión Marco Y, Raigón MD, Badal E. Redrawing the History of Celtis australis in the Mediterranean Basin under Pleistocene–Holocene Climate Shifts. Forests. 2023; 14(4):779. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14040779

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Varea, Carmen María, Yolanda Carrión Marco, María Dolores Raigón, and Ernestina Badal. 2023. "Redrawing the History of Celtis australis in the Mediterranean Basin under Pleistocene–Holocene Climate Shifts" Forests 14, no. 4: 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14040779

APA StyleMartínez-Varea, C. M., Carrión Marco, Y., Raigón, M. D., & Badal, E. (2023). Redrawing the History of Celtis australis in the Mediterranean Basin under Pleistocene–Holocene Climate Shifts. Forests, 14(4), 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14040779