1. Introduction

In Japan, planted forests cover 10 million ha or approximately 40% of the 25 million ha of the forest area, of which 65% are privately owned [

1]. The planted forest resources, it is mainly converted from primarily broadleaf forests to conifer forests Japanese Cedar (

Cryptomeria japonica) and Japanese Cypress (

Chamaecyparis obtusa), which were established after World War II have matured; half of them are over 50 years old and are now in their utilization period. Notably, the amount of timber produced increased from 15.1 million m

3 in 2002 to 31.2 million m

3 in 2020 [

1]. However, the Forestry Agency has found that the log supply from clearcutting is approximately 40% of the growing volume of planted forests accumulated, indicating that the resource must be utilized more efficiently.

The Japanese government has promoted forestry promotion policies, including the revision of the Forestry Basic Law in 1964, in response to the declining profitability of the domestic forestry industry against the backdrop of the strong yen and increasing timber imports [

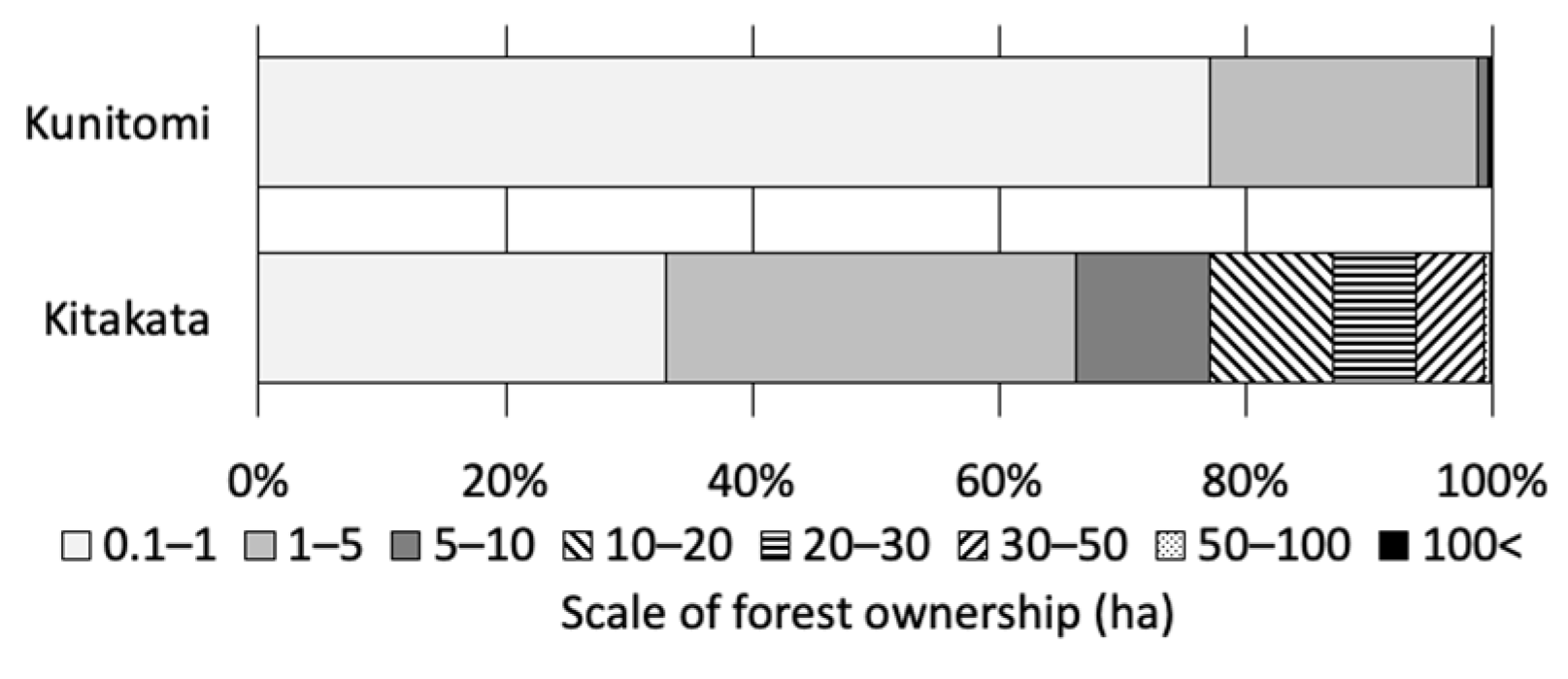

2]. Aggregating small-scale forest stands have been promoted as a policy measure to improve operational efficiency and reduce timber production cost in Japan, where the majority of forest owners are small-scale private forest owners (PFOs) [

3]. However, as planted forests matured and entered the harvesting stage, further aggregation of forest management was required. In 2019, the Forestry Agency has started a “New Scheme of Forest Management” (NSFM) to solve the following problems: the low willingness of PFOs to manage their forests, the disparity between the intentions of PFOs and forestry managers to expand the scale of their operations, the slow introduction of road network maintenance and high-performance machinery, and low productivity. The small-scale ownership of forest conditions is a major obstacle to efficient timber production, as 74% of forest areas owned by PFOs are less than 5 ha [

4]. The NSFM ensures the following: (1) A growth industry is compatible with proper forest management, (2) aggregation of forest management rights, not including ownership, to highly motivated and sustainable forestry enterprises, and (3) improvement conditions for aggregation of forest management [

4]. As part of this effort, in 2018, the government enacted a Forest Management Law to achieve effective timber production and appropriate forest management by aggregating forest management rights. Specifically, this law stipulates that PFOs must manage their own forests and are responsible for harvesting, silviculture, and nursery at the appropriate times. It also allows PFOs to entrust forest management to the municipality in accordance with PFOs’ future intentions. Forests suitable for forestry management are re-entrusted to forestry enterprises from the municipality according to their economic values, whereas the municipality manages those that are unsuitable. Thus, the NSFM is based on PFOs’ willingness to manage their forests in the future, and municipalities survey PFOs’ intentions to ascertain their willingness to do so. The survey selection criteria included planted forest owners without a forest management plan and forest management that had not been implemented for the past decade.

The Forest Environment Transfer Tax (FETT) allocation began in 2019 in Japan as a financial resource for municipalities and prefectures that will be directly responsible for NSFM. The FETT amount allocated to municipalities is calculated as follows: 50%, 20%, and 30% of the municipality allocations are based on the area of private forest plantations, forestry worker population, and municipality population, respectively. The area of privately planted forest is corrected according to the forest area ratio, with 1.5 for municipalities with a forest area ratio of 85% or more and 1.3 for municipalities with a forest area ratio of 75% or more but less than 85%. Notably, the criteria for determining the allocation amount deviate from the system’s intention [

5]. As FETT has only been operational for a limited time, system evaluation is a future concern. However, the actual situation regarding tax utilization is being assessed for prefectures [

6] and large cities [

7], prefectural support for municipalities [

8,

9], urban–rural partnerships [

10]. In addition, Ishizaki et al. [

11] mentioned the increased workload of municipal officials on the NSFM and the FETT administration.

The Forest Management Law, which directs the future management of the PFOs’ forest according to the PFOs’ willingness, may promote immediate timber production and forest improvement. However, because the transfer of rights related to the property rights of PFOs must be done cautiously, the development of PFOs willing to manage their forests must be balanced with the smooth aggregating forest management rights from PFOs unwilling to manage their forests. Clarifying the factors that influence future management intentions is thus necessary when considering the maintenance or enhancement of PFOs’ willingness to forest management.

Effective forest policy implementation requires identifying the determinants of PFOs’ decisions [

12] and developing forest policies that can influence PFOs’ behaviors [

13]. Forest owner typologies are being utilized to develop a method for identifying forest owner values [

14]. The typology studies are mostly based on ownership objectives [

15]. Previous studies noted that forest owners could be divided into five types: “economist,” “multiobjective owner,” “recreationist,” “self-employed,” and “passive owner,” based on the purpose of their forest ownership [

12,

13]. Boon et al. [

12] classified the Danish PFOs into three types: “classic owner,” “hobby owner,” and “indifferent farmer” based on a survey of PFOs’ interest in forests. Ingemarson et al. [

13] classified the Swedish PFOs into five types: “traditionalist,” “economist,” “conservationist,” “passive,” and “multiobjective,” according to the purpose of ownership, and showed differences in the forest ownership size, frequency of visits to their own forest, and presence of successors. Ficko and Boncina [

15] classified PFOs as “materialists” and “nonmaterialists”. On the other hand, some studies categorized PFOs focused on their forest management behaviors. The willingness of landowners to harvest woody biomass as a characteristic of woody biomass suppliers has been noted as a factor of ownership purpose, owned forest size, tree species structure and composition, and demographics in the southern United States [

16]. In contrast to these previous studies, an approach that categorizes PFOs according to their expressed future intention for their forest management and who identifies the underlying factors that can contribute to their decision-making process is required to clarify the issues involved in the NSFM, Japan.

The declining willingness of PFOs to forest management has been identified as a problem [

17], with multiple factors influencing PFOs’ management behaviors in Japan. Considering the PFOs’ forest status, these factors included forest ownership size [

18], especially planted forest size, and the distance between the residence and owned forest [

19,

20]. For PFOs’ perceptions and management behaviors, PFOs’ awareness of forests as property [

21], the awareness of owned forest boundaries [

22], perception of planted forest locations [

19,

20], and registration status [

19,

22] are noted. PFOs’ attributes were mentioned in terms of age [

23], occupation [

24], and the existence of successors [

24]. In addition, social relationships in local communities [

25], membership in a forest owners’ cooperative (FOC) [

22], deteriorated functioning of FOC’s regional organizations [

26], and residence or absence in the village have been identified as factors influencing the owner–local community relationship [

20]. Since the late 1990s, neglecting reforest postharvest has emerged as a problem resulting from PFOs’ poor forest management practices [

27]. Low prices of standing timber as economic factors [

28] and the failure to continue the management of forest divisions upon contract expiration as institutional factors contribute to reforest abandonment [

29]. Indicated by these results are the factors that define PFOs’ management behaviors and their perception of forests. However, studies on future management intentions are limited. Hayashi et al. [

24] mentioned regional differences in the factors that influence PFOs’ willingness to sell, as well as occupation and successors. Kushiro and Ito [

30] described that many PFOs, notably absentee village owners, want to disengage from forest management despite acknowledging the necessity of continuing forest management for reasons including uncertainty of inheritance, loss of boundary, and economic evaluation.

This study aimed to identify the socioeconomic factors affecting the future intention for forest management by classifying the PFOs’ future intentions.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The NSFM aims to realize efficient and sustainable timber production based on consolidating the forest land of PFOs with low future intentions. In this study, we administered a questionnaire to PFOs in Miyazaki Prefecture, one of the most active areas for timber production in Japan, to examine the socioeconomic factors that affect PFOs’ future intentions.

The PFOs’ willingness to manage forests varies by region [

32]. First, this study compared PFOs’ future intentions and the factors that might influence them across regions with different forest ownership sizes. In the small-scale region, 52.7% of PFOs desired to reduce the future management scale, whereas 70.9% of PFOs in the large-scale region desired to maintain or increase the management scale. A comparison of the two regions revealed the problems in private forest management. A common problem in small and large regions was the lack of awareness of forests owned by PFOs themselves. In particular, the fact that many PFOs were unaware of the size of their forests and planted forests indicated that PFOs do not have the sources to understand the value of their forests and consider the direction of future forest management. The importance of successors in forest management was also indicated. Additionally, this study revealed the challenges specific to the small-scale regions. The small-scale regions showed fewer future intentions to manage forests. Many PFOs were unaware of the maturity of their planted forests as well as the size of their forests. This may be attributed to the lack of understanding in many PFOs regarding the economic value of their planted forests, which may be one factor that reduces their willingness to manage their forests. Since many PFOs did not understand the value of their forests, their decision-making process regarding forest management was passive, as evidenced by the reasons for their decision to harvest their forest. Additionally, many PFOs wanted to quit forestry, whereas many did not reforest postharvest (

Table 12). These results indicated the need to develop a framework to provide PFOs with enough information to consider future management directions while implementing NSFM. At the same time, since small-scale regions are less willing to manage forests than large-scale regions, aggerating forest management right by municipalities is promising for the sustainable management of forests. However, since the workload of municipalities is excessive [

11], the prefectural government should support municipalities in small-scale areas with an emphasis on small-scale regions. PFOs’ low willingness to manage their forests may harm timber production, as owner identification and rights identification are particular barriers to timber production in the small-scale region [

33,

34]. Similar results were obtained for forest and planted forest size, as they influenced the current willingness to manage [

13,

16,

18,

19,

20].

Next, based on the survey results, we examined the factors affecting the future intentions of PFOs and the forest management behaviors of PFOs with low future intentions. The factor affecting future intention in small-scale regions was the presence of successors [

24]. No difference was found in the forest size [

13,

16,

18,

19,

20], which was considered a factor while analyzing the results, likely because the forest size was biased toward small-scale. In contrast, forest size, planted forest size, and planted forest maturity were the factors of forest condition that influenced the future intentions in large-scale regions. These results suggest that the economic value of forests affects the future intentions of the PFOs in large-scale regions. In addition, the existence of successors, the relationship with the FOC, and forestry’s position as an income source were also indicated as factors. Since it is essential to clarify the forest management behaviors of the PFOs with low future intentions to consider forestry policies, we summarized the characteristics of the forest management behaviors and attitudes of the D group. Among the common issues associated with both regions, the D group tended to have scarce forest management and be willing to dispose of their forestlands. Therefore, these PFOs tended not to implement reforestation because they had less emphasis on the reforest postharvest. In small-scale regions, few PFOs had future management directions and were unaware of the location and boundaries of their forests (

Table 13). The D group was not considered interested in the economic value of the forest. There could be two possible causes behind the lack of interest in economic value: first, they do not have information about the forests, and second, they must dispose of the forests due to the absence of successors to inherit them.

Under the Forest Management Law, municipalities must conduct surveys of PFOs’ intentions, and some have already begun to do so. Many PFOs are likely to respond to this survey without having all the facts they need to decide on their future forest management intentions. A procedural flaw can be identified regarding the intention survey, which encourages PFOs to make decisions without information about their forests. Before the survey, the government must provide an opportunity for the PFOs to know the location and boundaries of the forest, resource status, and other information. In addition, the omission of local forest ownership size from the criteria for allocating FETT to municipalities is a flaw of this system [

5]. FETT is used for “expenses related to forest improvement and its promotion, such as thinning, human resource development and securing of bearers, promotion of timber use, and public awareness.” The areas requiring enhanced forest improvement are those with low future management intentions. Furthermore, the results of this study suggest that many PFOs in small-scale regions would like to outsource management or relinquish their land. Therefore, the administrative burden of conducting the survey and forest management aggregation in municipalities with small-scale regions is considered high. For municipalities, securing finances is the most critical aspect of operating NSFM [

30]. These results suggest that FETT allocation criteria could still be considered based on the regional characteristics of ownership size. Differences were also observed in the factors that influenced the decision of forest PFOs to harvest between the two regions with different ownership sizes.

This study examined the factors that influence the PFOs’ future intentions in small and large regions by categorizing them by their future intentions and comparing the two types. Comparing the two groups revealed that the EM group prioritized economic benefits and the sustainability of the forest resource in their harvesting decisions. In contrast, the D group had more PFOs who wanted to relinquish their land and withdraw from forestry management. The EM group tended to own more forestland, suggesting that the size or economic value of their forest holdings influenced their future willingness to manage their forests. The D group was characterized by less frequent forest visits and a greater proportion of PFOs who lacked basic forest knowledge, such as area, location, and boundaries. These findings suggest that PFOs’ lack of knowledge about their forests may result in uninterested in forest management.

The existence of successors is an essential factor in the continuity of forest management [

24], in addition to the size, especially planted forest size [

18,

19,

20]. Therefore, information on the forest owned, forest area, and the availability of successors are factors influencing willingness to future forest management. The forest management behaviors of PFOs with low future willingness to manage revealed issues regarding forest sustainability. In terms of harvesting decisions, the EM group emphasized the economic benefits and sustainability of the resource. However, the D group saw the logging decision as an opportunity to withdraw from forestry management and passively made logging decisions. This suggests that forests owned by PFOs with low future intention goals are a source of the increased abandonment of reforested.

To better reflect effective forest policy through PFOs typologies [

14], examining the factors underlying the decisions of typified PFOs is necessary [

12]. PFOs who wish to reduce the size of their future management have poorer forest management behaviors and are likelier to abandon the reforested area. Therefore, the method of categorizing PFOs based on their future willingness to manage the forest with resource sustainability and efficiency of operations was considered reasonable. However, promoting the transfer of forests owned by PFOs with a low future intention to forest management is insufficient; measures are also required to increase PFOs’ willingness to forest management. Furthermore, PFOs must be given more opportunities to learn enough about their forests to make informed decisions about future management direction. Especially, the NSFM must consider the ways to develop forest information, provide PFOs with opportunities to obtain such information, encourage PFOs who are willing to manage their forests, and strengthen municipal work structures [

11].

Therefore, the role of FOCs who have a good understanding of the status of local forests is crucial [

26]. In large areas where the economic value of forests is relatively high, strengthening the relationship between PFOs and FOCs may be effective in motivating PFOs to manage the forests. It is expected that PFOs will be more likely to obtain information on their forests from FOCs, which will provide an opportunity for PFOs to recognize the economic value of their forests. In addition, since many PFOs are willing to dispose their lands in small-scale regions, the aggregation of the forest management rights by the municipalities will be required for sustainable forest management. As the workload of municipalities is expected to increase due to this policy, it will be necessary for the prefectural government to support the municipalities with small forest ownership in a focused manner [

6,

8].