Abstract

Riparian forests are rare and valuable ecosystems in Central Asia, both due to their significance for biodiversity and to their provision of vital ecosystem services to local residents. However, the actual forest use behaviour is under-researched, official figures may not be trustworthy, and the question of over-use is up in the air. This paper sets out to shed light on riparian forest use behaviour by local residents using the example of Ak-Tal Village upon the Naryn River in Kyrgyzstan: Which economic use patterns do they practice (focusing on fuel wood and pasture)? Which other ecosystem services do they recognise? Is there forest over-exploitation? To answer these questions, this study builds on local knowledge, by applying the methods of focus group discussions and a household survey. Results show an extreme discrepancy between official wood consumption figures (50–60 m3 p.a.) and figures based on household wood consumption (310–404 m3 p.a.). The forest also serves as an important winter pasture over the seven months between October and April (stocking density 0.61 livestock units/ha), but payments for these ecosystem services are low, with annually 40 KGS/ha. Local residents are aware of additional material and nonmaterial ecosystem services of the riparian forest. Opinions diverge upon the question if there is forest over-exploitation, potentially because different stakeholders have different concepts of an optimal forest status. Consequently, optimal forest use behaviour can only be defined by the local users themselves, e.g., in a future stakeholder dialogue.

Keywords:

riparian forest; fuel wood; wood pasture; agroforestry; ecosystem services; Naryn; Kyrgyzstan; Central Asia 1. Introduction

1.1. Setting the Scene

Human wellbeing depends on ecosystem services provided by the earth’s ecosystems [1]. People, while making use of the ecosystem services, tend to drive the corresponding ecosystems away from their natural stage. These manipulations of the ecosystems may either happen deliberately, aiming at “optimised” ecosystem services for the purpose of increasing human wellbeing; or they may happen rather accidentally or at least with a pinch of ignorance, resulting in an unintended loss in vital ecosystem services and a decrease in human wellbeing. External observers, including researchers, should be careful with their judgement whether the former or the latter is the case, because what they perceive as “degraded” might be “enhanced” in the eyes of the ecosystem users [2]. With this uncertainty in view, this study will describe how Kyrgyz inhabitants of floodplain villages use and see their riparian forest—using the example of Ak-Tal Village at the middle reaches of the Naryn River.

The study served as a preparatory step for village-based stakeholder dialogues and has been conducted within the context of ÖkoFlussPlan, a German–Kyrgyz project aiming at the preservation of selected ecosystem services in the floodplains of Naryn River. The proceedings of the stakeholder dialogues will be published in a separate paper.

1.2. Geographic Overview: The Riparian Forests of the Naryn River

Kyrgyzstan lies in Central Asia, landlocked between China, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, in a high mountainous region dominated by the Tian Shan Range, with only 10% of the country surface lying lower than 1500 m above sea level. The climate is continental, and in the high Tian Shan Mountains very cold [3], annual precipitation varying between 100 mm and 1000 mm [4]. Due to the rough topography and climate, high alpine wastelands cover about 45% of the country’s territory [4]. Pasture is the dominating land use type at 48%. The extent of croplands is limited to 7%. Forests cover only 5% of the country’s territory [5].

With a population of 6.6 million people on a state territory of close to 200,000 km2 the country is sparsely populated, and the vast majority live scattered in rural areas [3]. At a real GDP per capita around 5250 USD, the population average is poor, and the economy relies largely on remittances from people working abroad, from minerals extraction, and from agriculture [5]. Agriculture—including pastoral animal husbandry as an economic mainstay [6]—is by far the most important sector in terms of occupation, with a share of 48% [5]. The tremendous significance of pastoralism in Kyrgyzstan is underscored by both its dominance in land use types and occupation shares.

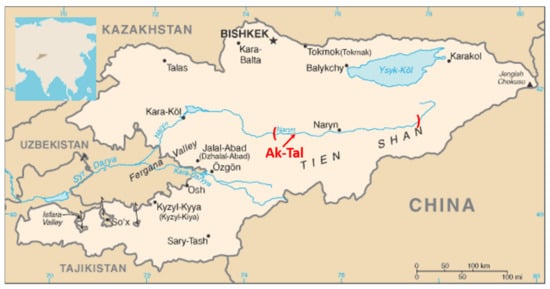

The Naryn River, Kyrgyzstan’s biggest river, flows from the Tianshan Mountains in the East of Kyrgyzstan westwards to the Kyrgyz–Uzbek border (cf. Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Naryn River in Kyrgyzstan; the braided section harbouring most of its riparian forests is indicated by ( ); the position of the main research site, Ak-Tal Village, is indicated by an arrow (adapted from [7]).

The annual average precipitation at the Naryn City climate station is only 300 mm, with a main rainy season in May and June, but snow and glacier melt of the surrounding mountain ranges additionally feed its run-off, resulting in a typical glacial discharge behaviour peaking in July. Its first 680 river kilometers are still in a natural state without any substantial dams and embankments—nowadays a rarity worth protecting among big rivers of the world. In the river section beginning at Eki Naryn, where its two headwater streams merge, it flows about 160 km down through a broad valley where it has all the space to meander freely, eroding older terraces, raising new gravel banks, forming floodplains with the natural patterns of active braided river reaches (cf. Figure 2). It is here that the Kyrgyz riparian forests, focal theme of this paper, have established predominantly. Due to the active meandering, all succession stages of riparian forests are present all along the riversides and river islands, from bar sediment surfaces to pioneer plots, to young pioneer forests, to fully established forests including disturbance-intolerant tree species and a diverse herbal layer. Dominant tree species are black poplar (Populus nigra), willows (Salix spp.), sea-buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides), and tamarisks (Tamarix spp.). This river section ends about 20 km downstream of Ugut Village, where the river enters narrow canyons. (The Naryn River has been described extensively by [8]—for more details about its corridor and hydrology see there).

Figure 2.

Riparian forests upon the braided Naryn River at Kulanak Village.

With forests accruing to only 5% of all Kyrgyz land use types, and with riparian forests accruing to only 5% of all Kyrgyz forest types [8,9], these forests represent just a tiny fraction of the Kyrgyz territory, yet they are of elementary importance from at least three points of view. First, from the viewpoint of international biodiversity conservation, the Naryn River’s dynamic riparian forest ecosystems have become rare in a world where most large river corridors are regulated by human constructions [8]. Second, from the viewpoint of the Kyrgyz national forest strategy as in the 1999 forest law, existing forests shall be managed sustainably and forest cover shall be increased [10], which in the Kyrgyz climatic conditions is hard to achieve without consideration of the riparian forests. Third, from the local viewpoint, provisioning, regulating and cultural ecosystem services play a crucial role for the livelihoods in the floodplain settlements. The catchment area in general is sparsely settled with only 6 inhabitants/km2 (CIESING 2005, cited in [8]), yet within the 160 river kilometres of special interest for this thesis, there are 26 villages and 1 city side-by-side situated alongside the river like beads on a string, all benefiting of the ecosystem services of the floodplain. In sum, these three viewpoints illustrate that conservation of the riparian forests is highly relevant, justifying a thorough pursuit of the topic.

While globally there is a vast array of literature on ecosystem services of riparian forests [11], in the Kyrgyz context, there is mainly one author who has previously been working on this topic. According to his interviews, the ecosystem services most requested by local inhabitants are, in descending order, provision of wood, recreational area, provision of sallow thorn, provision of pastoral land, erosion protection, and climate regulation. An additional expert interview indicated that grazing might be more important than the notion of the inhabitants suggested. The value of local ecosystem services is roughly assessed for fuel wood at 250 KGS/m3 (to be paid to the Forestry Administration), and for sallow thorn berries at 100 KGS/kg (market price).

1.3. A Short Historic Overview: Past Use-Patterns of the Riparian Forests

In the 20th century, big societal upheavals rejigged Kyrgyzstan several times, each time modifying the management of the natural ecosystems. Historically, the Kyrgyz were nomads, and despite the Russian colonisation during the late 19th century, nomadic pastoralism kept prevailing until the 20th century [12,13]. Headed by tribal leaders, they organised a complex pattern of mountain pastoralism (for definition see: [14], where people moved up and down the mountains according to the growth seasons, partially complying with very complex multi-annual rotation systems, all geared to the optimal distribution of grazing pressure [12,15]. In these systems, the winter pastures in the valleys were crucial (and the only ones people competed about) because the amount of winter fodder was the bottleneck that limited livestock levels [12]. These precious winter pastures presumably often comprised wood pasture in the riparian forests.

Under the pressure of the USSR, to which Kyrgyzstan had belonged since 1936 [5], the nomadic pasture society was brought to an end. Until the beginning of the 1940s, sedentarisation in the valleys was nearly completed, and livestock breeding had been collectivised [16], as cited in [8]. The now centrally organised pasture rotation was supported by modern means of production, such as import of winter fodder and transportation of livestock by truck and train, initially allowing an increase of livestock numbers. However, since the 1960s, permanent over-stocking had become the norm, and by 1990, 16% of the pastures, especially in the alpine grazing lands, were heavily degraded [12]. No detailed data could be found for the use intensity of the riparian forests in this period; however, three facts suggest that the use pressure must have increased. First, the sedentarisation in the valleys implied that people could access the forest for timber and fuel wood all year long. Second, the increase in collectivised livestock numbers increased the general grazing pressure. Third, the privately owned livestock (up to 10 sheep, 2 goats, 1 cow, and 1 horse per household) stayed in the village near pastures over all seasons, creating additional grazing pressure [12].

The breakdown of the Soviet Union resulted in the privatisation of sheep ownership and a sharp decline in sheep numbers [13]. Despite decreasing livestock numbers, the situation of the riparian forests further deteriorated. For one thing, the state-owned high mountain pastures—now leasable to private livestock owners—became less frequented due to logistical problems, thus increasing the grazing pressure on the lowlands. The Soviet feed supplements supply—most important during winter season—came to an abrupt end, further aggravating the grazing pressure in the valleys [13]. For another thing, the Soviet coal supply ceased suddenly, leaving the local inhabitants with no other heating sources but dried dung and wood from the riparian forests, with the consequence of severe logging activities [8].

In the 21st century, coal became available again, and the logging situation in the riparian forests might have improved somewhat [8]. Regarding the pasture situation, there seems not to be a clear trend. The new Law on Pasture, adopted in 2009 and amended in 2011, shifts the decision-making power from centralised governmental bodies that formerly were responsible for pasture lease, down to village-based democratic organisation: the Pasture Users Association (PUA) and its administrative body the Pasture Committee (PC). This might be a positive development because local bottom-up organisations may be more efficient in avoiding over-grazing [15]. On the other hand, livestock numbers have been on a steady recuperation pathway since the mid-1990s, continuously adding pressure to the pastures [17].

1.4. Knowledge Gaps and Local Knowledge

In remote rural areas of Kyrgyzstan, data availability and access to existing official data is challenging. Moreover, the reliability of statistical data must be viewed critically. There are considerable knowledge gaps, to which our research aimed at contributing.

In transdisciplinary research, the aim is to close knowledge gaps by exploring local expert knowledge and perceptions [18]. This relevant expert knowledge is with local people, landowners, land users, policy makers and administrative staff, i.e., with different stakeholder groups.

By using different methods and tapping to different sources, robust knowledge can be co-produced by researchers and stakeholders. There is increasing agreement among scholars in natural resource management that local knowledge, perceptions, and strategy development can be created by a combination of social science methods, interviews, surveys, focus groups—and that this knowledge is relevant for finding strategies for sustainable natural resources management [19].

1.5. Research Questions

The Naryn River’s riparian forests are exposed to a high historic and present use pressure, driven mainly by the economic need for fuel and fodder, with the problem of potentially unsustainable levels of fuel wood extraction and forest grazing (over-exploitation) [8]. However, before one can distinguish if the present use patterns are sustainable—from the viewpoints of either biodiversity conservation or optimised provision of ecosystem services—it would be necessary to actually describe and understand the present use patterns.

This paper has the goal to investigate the local residents’ forest use patterns and their views on the forest. To reach this goal, the paper describes the inter-relation between people and forest along the following four research questions:

- Which economic use patterns do inhabitants practice (focusing on fuel wood and wood pasture)?

- Which other ecosystem services (beyond fuel wood and wood pasture) do they recognize?

- How do local inhabitants assess the question of forest over-exploitation?

- Which measures do they propose to reach sustainable use levels?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study Area—Ak-Tal Village and Its Riparian Forest

Ak-Tal Village lies 80 km downstream in the West of Naryn City (cf. Figure 1) and belongs to the Ak-Talaa District. Its 234 rural households are arranged alongside the country road, squeezed between the river in its North and mountains in its South, with an east-west length of 3 km and a width of 500 m (cf. Figure 3). The eastern part of Ak-Tal is directly adjacent to the riparian forest, while the middle and western part of the village are separated from the forest by a wedge of irrigated barley fields—but even the remotest household can reach the riparian forest in less than 1 km walking distance (Google Earth, field observation). The position on an older fluvial terrace, approximately 5 to 10 m above the present riverbed, provides a leveled terrain suitable for irrigated agriculture and protects the village from seasonal flooding, while at the same time allowing for easy access to the forest and the river (field observation).

Figure 3.

Ak-Tal Village upon the Naryn River, its attributed riparian forest area (blue line), and the 40 survey locations of the Ak-Tal Household Survey 2020 (blue dots).

The riparian forests around Ak-Tal Village are state property managed by the Ak-Talaa District Forestry Administration. The Forestry Administration attributes certain use rights to Ak-Tal Village for a forest area of 8.9 km2 situated on the southern riverside, adjacent to the village (FGD 2 2019; oral information by Florian Betz 2021). Beginning approximately 4 km west of the village, this area stretches about 14 km to the east like an undulating green ribbon, with a width varying between 100 m and 1.5 km (cf. Figure 3; oral information by Bolot Sadyrov, Forestry Administration of Ak-Talaa). The forest can be discriminated into two different main types. One type, predominant in the western part, lies on the same fluvial terrace as the village itself and rather shows characteristics of a semi-open pasture landscape with much open space, old single trees, light groves, shrubs, and signs of heavy grazing. The other type, predominant in the eastern part, lies below the old fluvial terrace on a level that is still reachable for seasonal flooding and shows a dense structure with nearly closed canopy cover and partially impermeable thickets, constituted by younger trees with seemingly higher growth rates (field observation). Due to the semi-open characteristics, only 4.7 km2 of the designated forest area are actually covered with trees (oral information by Florian Betz 2021).

Judging from the general geographic settings (Google Earth) and from the site conditions (field observations), Ak-Tal is not an outlier among the row of villages along the Naryn River but rather a typical one. Comparative pilot interviews conducted in Ak-Tal and two other villages (Emgek-Talaa and Tash-Bashat) also revealed that housing, social structures, economic activities, and ecological issues were pretty similar (9 pilot household interviews, 2019). We can thus assume the forest use structures of Ak-Tal Village to be fairly representative for other river villages along the Naryn River’s middle reaches.

2.2. Methods Used

The core method to establish the subsequent results was a household survey conducted in February 2020 in Ak-Tal Village (Ak-Tal HHS 2020). A pilot series of 9 semi-structured interviews that had been conducted beforehand in 2019 in the villages of Ak-Tal, Emgek-Talaa, and Tash-Bashat gave a good orientation for content and form of the relevant questions to be asked in the final quantitative survey with predominantly close-ended questions. The survey questionnaire was consequently developed by three partners: Eberswalde University for Sustainable Development (HNEE, Germany), Technische Hochschule Ingolstadt (THI, Germany), and Naryn State University (NSU, Kyrgyzstan). Apart from questions about livelihoods and the general living conditions, the total 99 questions of the questionnaire split into two main thematic hotspots, according to the research interests of the two respective research groups: (a) energy demand, energy provision, and perception of the energy situation (THI), and (b) use and perception of the riparian forest (HNEE). These two thematic hotspots had to be amalgamated into one joint questionnaire for synergy reasons, but only the latter is of relevance for this paper (the former was published in a separate paper [20]). NSU supported the establishment of the questionnaire with advice and translation into Kyrgyz.

The area of Ak-Tal Village with its 234 households (Google Earth count) was divided into 10 geographic sectors representing core, eastern and western extremities of the village, as well as remoteness and closeness to the riparian forest; and in each sector, 1 out of 6 households were sampled, with a total sample size of n = 40 (cf. Figure 3).

The actual survey was conducted over 4 consecutive days in February 2020 by two interview teams, each constituted by 1 researcher from one of the German institutes, 1 researcher and translator from NSU, and 2 to 3 NSU students being introduced to conducting interviews. Each interview had a duration of half an hour to 1 h, including photos to be taken. Questions were posed in Kyrgyz and answers directly taken down in Kyrgyz.

Subsequently, the answer sheets were transferred into Word documents and translated into English by NSU staff, and then further transferred into Excel and evaluated partially by semi-qualitative methods and mainly by simple statistical methods (averages, sums, projections, and correlation analyses). Household income data collected during the survey prove to be too fragmentary and inconsistent and had to be complemented by an additional wealth index that was calculated from the three indicators as follows:

- household livestock units per capita (weighted 50%);

- household living space per capita (weighted 25%);

- the existence of additional professions beyond farming (weighted 25%).

We deemed household livestock units per capita to be the strongest of the three indicators (and therefore weighted it heavier than the other two) because in rural Kyrgyzstan, livestock is regarded as the safest form of value storage (Kabar 2019; Sparkassenstiftung 2019), and therefore, flocks have an equivalent function to deposit accounts (FGD 2 2019, oral information Kuban Akmatov and Nadira Degembaeva 2020).

Expert interviews were conducted twice in October 2019 in the format of focus group discussions (FGDs 1&2 2019): The first took place in the Naryn District Forestry Unit and had the leading staff of the local forestry unit. The second took place in the local administration of Ak-Tal and had the mayor of Ak-Tal, a representative of the Ak-Tal Pasture Committee, and leading staff of the Ak-Talaa District Forestry Administration to which the riparian forest of Ak-Tal Village belongs.

The following activities, all undertaken between October 2019 and February 2020, added to the overall picture:

- several road trips over a 140 km stretch along the Naryn River, from its conjunction at Eki-Naryn (Tash-Bashat Village) down to the village of Ugut, with several intermediate field stays;

- occasional interviews with knowledgeable inhabitants of Ak-Tal Village;

- 10 days of field observation in Ak-Tal and its riparian forest, including 2 transect forest walks;

- personal information from affiliated researchers.

3. Results

3.1. Use of Ecosystem Services

The riparian forests provide vital ecosystem services to riparian villages along the Naryn River. However, while making use of ecosystem services, there is the permanent danger of degrading the underlying ecosystems and thus reducing their flow of services. This is especially true for the activities of fuel wood acquisition and forest grazing because they directly kill or harm the trees [8]. For this reason, the use patterns of these two services will be studied in detail, while the other ecosystem services will be treated in a synoptic way.

3.1.1. Provision of Fuel Wood

The most important provisioning ecosystem service of the riparian forest of Ak-Tal is the provision of fuel wood, with 70% of the households using it (Ak-Tal HHS 2020).

According to the Naryn District and Ak-Talaa District Forestry Administration staff, and according to the mayor of Ak-Tal village, a massive illegal over-exploitation of the riparian forests began after the breakdown of the Soviet Union because the habitual coal deliveries stopped arriving and people were in desperate need for fuel to survive the winters. The fuel situation stabilised within roughly five years after the breakdown, and since about the year 2010, illegal harvesting ceased to be a major issue, as they said. In fact, staff from the Naryn District Forestry Administration stated to be aware of ongoing illegal harvesting and to tolerate it in certain socially precarious cases, e.g., when poor households need wood for winter heating (“…the foresters are also from the villages and we know each other…” FGD 1 2019). The present legal framework bans the cutting of living trees completely. The only legal way to obtain riparian fuel wood is to buy a “wood ticket” from the Forestry Administrations at 250 KGS/m3, whereupon a forestry worker assigns a corresponding lot of dead wood to the buyer who is then allowed to extract it within a certain time frame (FGD 1&2 2019, Ak-Tal pilot household interviews 2019). Annually, wood tickets for an amount of 50–60 m3 are sold to Ak-Tal Village inhabitants (FGD 2 2019).

The Ak-Tal Household Survey 2020 (Ak-Tal HHS 2020) revealed that a majority of the village households (70%) use riparian wood as a heating source, making it the second most widespread heating source after coal (100%) and before dung (67%) and wood from their own trees (23%; cf. Figure 4; Table 1). (Electrical radiators exist here and there but play a minor and temporary role.) On average, village households buy 1.32 m3 of riparian wood per year. Projections on the total 234 households of the village suggest a legal riparian wood consumption of 310 m3 per year in Ak-Tal village, which contrasts steeply with the officially stated 50–60 m3 per year (compare above).

Figure 4.

Energy carriers stored in the courtyards: (a) riparian wood and coal; (b) coal and dung. Ak-Tal Village, 2020.

Table 1.

Fuel types used in Ak-Tal Village, projected from the Ak-Tal Household Survey 2020.

The village inhabitants usually gather fuel wood in autumn, and all households using riparian fuel wood stated they had bought the corresponding “wood tickets”. Interestingly, despite the official statement of a fixed price at 250 KGS/m3, households stated to pay very different prices, between a minimum of 200 KGS/m3 (1 household) up to 1000 KGS/m3 (1 household), with a majority paying 500 KGS/m3 (10 households; variation coefficient: 39%). One may argue that people in the interview situation did not remember the payments made several months ago properly, yet this can, to say the least, not be the only reason, because the interviews revealed a far lower price variety for coal (between 1000 KGS/t and 3500 KGS/t with an absolute majority of 25 households stating 3000 KGS/t; variation coefficient: 17%). Another partial reason may lie in the interviewees accidentally adding their transportation costs (rent for trucks and horse carts) to the ticket price in their answers (interview Barchynbek 2020). Still, this divergence remains remarkable and, in combination with the divergent figures on the overall annual amount of wood, raises doubts about the functionality of the “wood ticket” system.

Transect walks through the riparian forest of Ak-Tal show that despite the legal framework, cutting of living trees still goes on. In the west, higher-lying semi-open forest, the traces of living branches cut off and old trees deliberately harmed (in order to turn them into dead wood) are noticeable all over (site observations October 2019 and February 2020). In the eastern low-lying dense part of the forest, various groups of local people could be seen and heard cutting living trees and making the wood ready for transportation (site observations February 2020; cf. Figure 5b,c).

Figure 5.

Forest use: (a) Wood pasture in the wintery riparian forest. (b) Illegal cuttings of two consecutive years. (c) Donkey ledge ready for transporting illegally harvested fuel wood. Ak-Tal Village, 2020.

Asking interviewees about illegal activities is always difficult, yet in the Ak-Tal HHS 2020, 10% of the interviewed households answered the blunt question for illegal harvesting with a clear “yes”. Only one household of the survey was willing to specify the annual amount, claiming to illegally harvest 2–4 m3 per year. In the 2019 pilot household interviews, another Ak-Tal household had stated to illegally extract 4–6 m3 per year. Taking these figures as a basis allows us to roughly estimate the annual illegal wood extraction from the Ak-Tal riparian forest at 94 m3 (average of 4 m3 projected by 10% of the 234 Ak-Tal’s households). Putting this rough estimate into perspective, it means that illegal harvest could be nearly double the size of the officially sold 50 to 60 m3 per year (Table 2). Additionally, the fact of 30% of the interviewed households claiming to have observed other households in illegal harvest activities suggests the existence of a dark figure. Finally, there seems to be lacking clarity of what actually counts as illegal harvest; five households who had claimed not to practice illegal harvest innocently claimed to cut living branches for fuel, an activity that is also banned.

Table 2.

Projected annual amount and value of the Ak-Tal Village fuel wood harvest according to different sources.

Fuel wood provision is an important ecosystem service of the Naryn River’s riparian forests. Expert interviews (FGDs 1&2 2019) and the Ak-Tal household survey 2020 can serve as a basis for estimating size and value of this service. Depending on the underlying sources, the size of the service ranges between annually 50 m3 at a value of 12,500 KGS (FGD 2 2019), and 404 m3 at a value of 199,000 KGS (Ak-Tal HHS 2020).

The service is generated on a total forest area of 890 ha. Expressing the size and value of the service in relation to the forest area makes it more comparable. Depending on the underlying sources, the annual harvest amount ranges between 0.06 m3/ha at a value of 14 KGS/ha (FGD 2 2019) and 0.45 m3/ha at a value of 223 KGS/ha.

Are there certain groups of inhabitants that use this service more than others do? An analysis of the correlation between riparian wood consumption and wealth index showed that the poorer households tend to buy more riparian fuel wood than the wealthier (correlation: −0.378; p-value: 0.018), most probably for the simple reason that the wood is cheaper than coal. Further correlations were not detected—e.g., the distance between the housing area and the forest does not influence the wood consumption (correlation: −0.007).

3.1.2. Provision of Pasture

The provision of pasture is the second most important provisioning ecosystem service of the riparian forest of Ak-Tal, with 32% of the households using it (Ak-Tal HHS 2020).

Nearly every household of Ak-Tal engages in animal husbandry (39 of 40 sample households), making it the biggest economic branch of the village. The Strategy Plan 2022 of the Ak-Tal Village Self-administration underpins this impression: the only economic development plan lies in increasing the efficiency of livestock farming (switching from quantity to higher quality by breeding with certain pedigree livestock). Currently, the village has mainly sheep (69%), goats (15%), cows (11%), and horses (4%), and the average household possesses 35 pieces of grazing animals with roughly 24 sheep, 5 goats, 4 cows, and 2 horses (Ak-Tal HHS 2020). The Pasture Committee determines the carrying capacity of the pastures calculating in “livestock units”, where cows and horses have a value of 1 livestock unit, while sheep and goats have a value of 1/5 livestock units (FGD 2 2019). According to the Pasture Committee, the village of Ak-Tal has 28,000 ha of pasture at command, with a carrying capacity of 5000 livestock units, and it is currently not rated as overgrazed because the present stock of Ak-Tal amounts to only 3000 livestock units (FGD 2 2019; 2640 livestock units according to projections from the Ak-Tal HHS 2020). However, a more detailed view shows that some of the high mountain pastures are practically unused because they are currently not accessible, while some locations of the village near pastures—of which the riparian forests form a part—are under pressure and are partially overgrazed (FGD 2 2019).

The Pasture Committee is the elected executive body of the Pasture User Association, i.e., the union of all livestock owners of the village, and these organisations manage the pasture as a governed commons in the sense of Elenor Ostrom (Ostrom: Governing the Commons; for details and issues of these two bodies cf. Shigaeva et al. 2016 [15]. They establish pasture plans for 1 and 5 years in advance, decide on overgrazing and maintenance work to be done, sell the mandatory “grazing tickets” to all households herding on common pasture, and they punish illegal grazers with a fine of 5000 KGS. The grazing itself is generally organised as an annual cycle of four steps: from winter in the so-called “village-near pasture”, to spring in the middle pasture, to summer in the high-mountain pasture, to autumn back in the middle pasture, and finally back to the village-near pasture for the following winter. Paid professional herders care for the spring, summer and autumn grazing, while the village near-winter grazing is often done by the individual livestock owners (Ak-Tal HHS 2020).

According to the Ak-Tal Household Survey 2020, the village near-winter grazing period is from October to April (7 months). During that time, the households have different feeding options for their livestock: (a) herding in the riparian forest, (b) herding on other communal land (i.e., the hilly pastures at the back of the village), (c) herding on their own arable land, and (d) courtyard and stable feeding. A total of 32% of the households claimed to graze their livestock over 3–7 months in the riparian forest, partially combined with other feeding options (Table 3). Their statements regarding their number of livestock units and the number of winter months herded in the riparian forest allow us to very roughly estimate the overall extent of riparian forest grazing and stocking density.

Table 3.

Projected overall extent of riparian forest grazing, stocking density (Ak-Tal HHS 2020), and annual value of the pasture (FGD 2 2019) in Ak-Tal Village.

The average daily amount is 514 livestock units in the riparian forest, and the averaged stocking density is 0.61 livestock units per hectare depict hypothetic maxima. The real figures are probably somewhat lower because on very cold winter days, most households avoid the strenuous work of active sheep herding and only drive their cows into the forest, which, contrary to sheep, return to their home stables on their own in the evening (interview Inak Kudaiberdiev 2020). This notion is supported by a 10 km transect walk on a −10 °C February day all along the riparian forest, where mainly cows and some horses were sighted (site observation 2020). In spite of this constrictive remark, these figures demonstrate how substantially the riparian forest supports the most important economic branch of the village, by the provision of pasture.

The economic value of this ecosystem service, however, is presently expressed only by an annual lump sum payment of 20,000 KGS, which the Pasture Committee makes to the Forestry Administration (FGD 2 2019).

3.1.3. Other Ecosystem Services

Besides the most obvious provision of economically significant goods, forests have many other functions that human populations can perceive as services. The relevance of other ecosystem services of the riparian forest, in the perception of the local population, was examined in a synoptic way (cf. Figure 6) with this simple question: “Besides fuel wood and grazing, what is the riparian forest good for, in your view?” The interviewees of the sample households replied to this question each naming between one to six additional items which can be classified according to the three basic categories of final ecosystem services: provisioning, regulating, and cultural [1].

Figure 6.

Share of Ak-Tal Village inhabitants attributing certain ecosystem services to their riparian forest (Ak-Tal HHS 2020).

First, as provisioning ecosystem services besides fuel wood and pasture, respondents named the provision of sea-buckthorn berries (28%) and fishing (28%). Sea-buckthorn berries have a local market value of 100 KGS/kg and are processed into jam. The collection of sea-buckthorn berries can be substantial enough to create a certain additional household income [8] (p. 31). Fishing seems not to be very productive, and its recreational value may be more important than the actual catch (site observations 2019 and 2020).

Second, as regulating ecosystem services of the riparian forest, respondents named erosion protection (28%) and local climate regulation (25%). The Naryn River meanders freely without artificial hydraulic regulation, recently eroding the old Ak-Tal River terrace as close as 30 m to the village’s barley fields. The existence of deep-rooted riparian trees may slow down the erosion. As for local climate regulation, the forest filters dust and moistens and cools the air, contributing to agreeable local climate conditions.

Third, as cultural ecosystem services, a great number of respondents named recreational (63%) and aesthetic (35%) services, making this category appear as a very important one. Local people have summer picnics and walks in the riparian forest as a common recreational activity, and they perceive it as an area of great scenic beauty.

In sum, the survey revealed a broad awareness in the local population about multiple ecosystem services of the forest, far beyond the obvious monetary benefits.

3.2. The Local Perspectives on Forest Over-Use

In the eyes of the local Forestry Administration, wood over-harvesting happened mainly in the 1990s and ceased to be a problem, although illegal wood extraction has persisted as a problem (FGD 1&2 2019). According to the local Pasture Committee, over-grazing is happening in some parts of the village near pasture (FGD 2 2019), which includes the riparian forest. From the biodiversity point of view, the mollusc species diversity is reduced on the high-lying terrace of the riparian forest north and west of the village, probably due to over-grazing (oral information from Hans Schmidt, 2020). From the botanical view, some areas of this terrace show concentration of Salvia spp., indicating over-grazing (oral information from Magdalena Lauermann, 2020). Observed from space by remote sensing, the terrace also shows a decreasing Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) over the last years, indicating reduced plant cover, which could be due to both over-use or natural desiccation (oral information from Magdalena Lauermann and Florian Betz, 2021).

What do the local inhabitants say? Is there currently forest over-use in terms of over-grazing or fuel wood over-harvesting, in their eyes? Which potential measures could they imagine to prevent future over-use? The Ak-Tal Household Survey 2020 approached these issues each with open questions to which respondents could answer in free sentences. These free answers first had to be analysed qualitatively in order to develop fitting categories for them, before they could then be assessed quantitatively.

3.2.1. Fuel Wood Over-Harvesting

“Do you presently see signs of unsustainable/over-harvesting of wood in the riparian forest?” Some respondents answered this question with a simple “Yes” or “No”, while other respondents added explanations, such as this: “No, only dried branches of the trees can be taken”. Some respondents avoided a clear commitment to one or the other (“At the present time, less wood is taken”.), while others stated their lack of knowledge (“I do not know”).

After categorising all answers in either (a) negative or (b) undecided or (c) positive or (d) unknowledgeable, the divergent perspectives of inhabitants on the question of fuel wood over-harvesting can be expressed in percentages. A vast majority of 60% sees no present problem of over-harvesting, while 17.5% do. Another 17.5% are undecided, and 5% do not know (cf. Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Wood over-harvesting assessment by inhabitants of Ak-Tal Village (Ak-Tal HHS 2020).

The recognition of fuel wood over-harvesting does not show significant correlations either with (a) the amount of fuel wood used or with (b) wealth or with (c) the distance between home and forest, or with any other researched item.

Interestingly, one of the survey respondents stated that the forest was partially too dense, harming the wool of the sheep passing through. On another occasion during a transect walk in winter 2020, the authors spotted a family going for illegal harvest with a donkey-drawn sledge and a saw sticking under the saddle; and upon the question what they were doing, they answered that they were going to cut trees in the eastern, lower-lying part of the riparian forest because the trees over there were “too dense”.

3.2.2. Over-Grazing

“Do you presently see signs of unsustainable/over-grazing in the riparian forest?” Similar to the chapter above, respondents answered this question with a simple “Yes” or “No” or with additional words, such as, “Over-grazing kills the young trees”, or “I think, there is no harm in the grazing. We do not graze in the tree nursery. The livestock graze only the grass in the forest”. Other answers are so vague that they can be interpreted in both directions (e.g., “There is grazing”).

The divergent opinions of the inhabitants balance each other, with a narrow majority of 37% seeing an actual over-grazing problem, against 30% seeing no problem, and with 33% undecided (cf. Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Over-grazing assessment by inhabitants of Ak-Tal Village (Ak-Tal HHS 2020).

Those who stated an over-grazing problem in the riparian forest correlate (a) with those that live closest to the forest (correlation: 0.409; p-value: 0.010) and (b) with those that spend most time herding their livestock in the forest during winter (correlation: 0.385; p-value: 0.015). These findings can be summarised in the statement that those who deal with the forest the most intimately and probably know the forest area best tend to be the ones who recognise over-grazing.

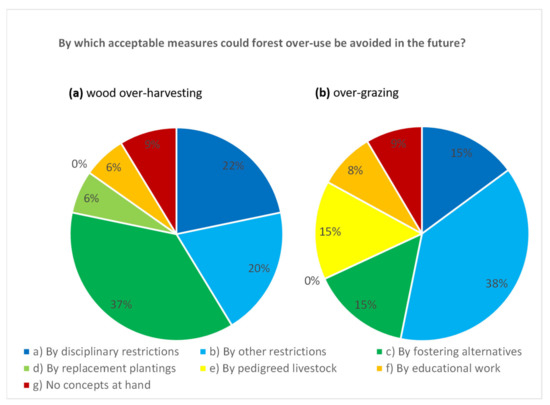

3.3. The Local Perspectives on Potential Measures against Forest Over-Use

For the purpose of developing future strategies apt to reduce forest over-use, it is meaningful to understand which measures are feasible and acceptable in the local context. The opinion of the local people who are the very forest users, in terms of both fuel wood extraction and forest grazing, is key here. To that end, the Ak-Tal Household Survey 2020 featured the following open questions: “By which acceptable measures could unsustainable/over-harvesting of wood be avoided in the future?” and “By which acceptable measures could unsustainable/over-grazing [in the forest] be avoided in the future?”

Respondents could answer these questions in free sentences. The answers covered a broad range of potential activities, some respondents also proposing various measures. The single proposals were analysed qualitatively and structured into different categories before they could be analysed quantitatively. The following categories emerged from the qualitative analysis:

- Disciplinary restrictions—The assignment to this category was triggered by the key words “control”, “order”, “disciplining” and “use of rangers”. For example: “There must be order”, or “By disciplining”, or “By improving the functioning of rangers to protect the forest”.

- Other restrictions—The assignment to this category was triggered by the key words “law”, “forest protection”, “safeguard the forest”, “fencing”, “limitation of livestock numbers”, and “courtyard feeding”. For example: “The law must take effect”, or “We need to strengthen the safeguard of the forest”, or “We need to fence the forest”.

- Fostering alternatives—In the question about reducing fuel wood over-harvesting, the proposed alternatives were coal, dung, solar, biogas, gas, and electricity, for example: “Reducing the price of coal, to be able to get enough of it”. In the question about reducing over-grazing, the proposed alternatives were to prepare more hay or other winter fodder, for example: “By preparing hay for the livestock”, or “By preparing more fodder”.

- Replacement plantings—This measure was only proposed in the question about avoiding future wood over-harvesting, for example: “By planting trees”, or “By new seedlings”.

- Pedigreed livestock—This measure was only proposed in the question about avoiding over-grazing, for example: “We need to have pedigreed sheep and cows, and then we can decrease the amount of livestock and save the forest”, or “We need to decrease the number of livestock and we need to transition from quantity to quality”.

- Educational work—The assignment to this category was triggered by the key words “explanatory work” and “good behaviour”. For example: “By explanatory work for the people, by explaining how important the forest is”, or “By good behaviour”.

- No concepts at hand—Some people expressed either that they saw no need for action at all, or that they did not have ideas at hand, or that they did not believe in the success of any measures. For example: “Nowadays, this problem is no longer existent, and I have no proposal about that,” or “I do not know,” or “It cannot be changed.”

“Law-and-order” policies seem to be very important in the eyes of local inhabitants when it comes to the question of how to prevent future forest over-use (cf. Figure 9). In the question of preventing wood over-harvesting, 42% of the proposals referred to restrictions (22% disciplinary restrictions, 20% other restrictions). In the question of preventing over-grazing, even 53% of the proposals referred to restrictions (15% disciplinary restrictions, 38% other restrictions).

Figure 9.

Assessment of Ak-Tal Village inhabitants regarding acceptable measures to prevent future forest over-use (a) referring to wood over-harvesting and (b) referring to over-grazing (Ak-Tal HHS 2020).

The second most significant policy, from the perspective of the local inhabitants, seems to lie in the creation of alternatives. This is especially true in the question of how to prevent future wood over-harvesting, with 37% of the proposals referring to fostering energy alternatives such as coal, dung, solar, etc. In the question of how to prevent over-grazing, 15% of the proposals referred to providing alternative winter fodder, such as hay.

Another important proposal to prevent over-grazing (15%), which is also backed by the local self-governance of Ak-Tal, is switching from the present livestock breeds to pedigreed breeds, in hope of creating the same production value as before while using less fodder.

Replacement plantings in the riparian forest (6%) and educational work (6–8%) count among the least-proposed measures.

Restrictions are seen as an acceptable measure against over-harvesting more often by the wealthier than by the poorer inhabitants of Ak-Tal Village (correlation of 0.318 between restriction proposals and the Ak-Tal wealth index; p-value: 0.048). Other correlations were not detected.

4. Discussion

Our research brought light to interesting aspects of the riparian forest use behaviour in Kyrgyzstan. With regard to the use of fuel wood, it shows the exemplary riparian forest of Ak-Tal Village to be in a difficult place. On the one hand, expert interviews showed clear rules for supplying the local inhabitants with necessary fuel while steering the forest exploitation within safe boundaries: with a ranger controlling illegal harvest, and selling wood tickets at a fixed price of 250 KGS/m3, for a total annual wood amount of only 0.06 to 0.07 m3/ha. These findings about the wood acquisition mechanisms and the official wood ticket price back the findings of the previous literature [8]. On the other hand, a household survey revealed very diverging wood prices between households, with an average wood ticket price roughly double as high as the official price, and a wood consumption via the wood ticket system five to six times higher than the official figures suggest. This discrepancy indicates a massive problem within the wood ticket system of the village, probably hinting to corruption, and we recommend it to be examined by an external auditing agency. In addition to that, illegal harvesting turned out not to be a minor activity, but it potentially runs up to nearly double the official harvest amount. These problematic issues are new findings that widen the previous state of research. There is no information if other river villages feature the same problems, yet it seems worthwhile to take a close look at these procedures in all those villages that work with similar wood ticket and ranger systems. In general, the official fuel wood price seems very low, with the local Forestry Administration annually taking in no more than 15,000 KGS from a forest area of 890 ha—the counter value of one and a half sheep. If desired, higher wood prices combined with better rule enforcement might reduce the fuel wood pressure on the forest substantially. Adding energy efficiency measures to the old residential houses might alleviate the situation further [20]. A demonstration house to display such energy efficiency measures is currently built in Ak-Tal Village [21].

With regard to wood pasture, the results showed the riparian forest to be an important economic factor for livestock farming. During the seven winter months, the livestock cannot stay in the mountains but must be brought down into the valley. A total of 32% of the Ak-Tal Village inhabitants depend on wood pasture in the riparian forest to help their livestock through the winter, with an average daily stocking density of 0.61 livestock units/ha between October and April. This information confirms the importance of wood pasture, assumed in the previous literature [8], and backs it with data for the first time. The value of this ecosystem service is currently expressed by an annual payment from the Pasture Committee to the Forestry Administration in the amount of 20,000 KGS—an equivalent value of two sheep for a pasture of 890 ha. Not only is this a very low price, the fact of it being a lump sum payment additionally constitutes a perverse incentive for livestock owners to drive their livestock into the forest because the service is paid for anyways. If local actors want to regulate the intensity of wood pasture, individualised payments (per household or per grazing unit) might be an interesting tool.

The results about other ecosystem services of the riparian forest (besides fuel wood and wood pasture) showed a widespread recognition of services beyond direct material benefits. The services discovered in the previous literature [8] could all be confirmed, and the list could be enlarged by the items of fish and landscape aesthetics. Especially cultural ecosystem services are very prominent in the minds of the local people. This hints to a deep-rooted personal inter-relation between the people and the forest, which may turn out as a mainstay for potential conservation efforts.

Is the riparian forest over-used? Local users rather tended to deny this for the question of fuel wood harvesting (some even claiming the forest to be under-harvested). However, they were very split over the question of wood pasture, with 30% denying over-grazing, 33% being undecided, and 37% affirming it. For one thing, this means that if there is forest over-use in the eyes of local residents, then it is rather due to grazing than to fuel-wood harvesting. For another thing, the wide split over the question of over-grazing indicates that among local residents, there must be different concepts of how a good riparian forest should look. The interesting thing about the question of forest over-use is that there cannot be one single answer to it, because the fine line between over-use and optimal forest use always depends on our underlying final objective. Are we trying to optimise the forest with regard to a steady wood production as our final objective? Or with biodiversity conservation in our minds? Are we trying to cultivate it towards a perfect wood pasture? Shall we measure optimal forest use based on the flow of regulating and cultural services that make the nearby village a safe and pleasant place to live for the inhabitants? Shall each of the above-mentioned objectives be reflected? If so, then in which balance? Finally, the intended forest state that delivers the optimal bundle of intended ecosystem services for the village and the country can only be negotiated between the relevant user groups themselves. Seen from this perspective, no external authority can ever answer the question of over-use. A future sustainable management plan for the riparian forests can only be forged by informed dialogues among all relevant stakeholders.

With regard to potential acceptable measures that inhabitants could imagine to be applied in order to control potential forest over-use, it is striking to observe that pricing mechanisms do not play any role. Instead, many proposed the provision of alternatives, such as other fuel types to replace wood, and other winter fodder to replace wood pasture, yet the financial resources for these alternatives remain unspoken. Most proposals, however, referred to “law and order” policies. While it is encouraging to see that many inhabitants want to safeguard the forest even by adopting rigorous measures, any actor pushing for such restrictions should keep in mind that the poorest, who called for such measures the least, have the strongest dependency on fuel wood and will feel the economic effects directly by the heating temperature in their living rooms.

As stated above, the question of optimal forest use is dependent on individual preferences, and the perfect use form can only be negotiated between the relevant actors themselves. We envisage the future of the Naryn River’s riparian forests to be shaped by stakeholder dialogues, backed by scientific information on river dynamics and climate change issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and M.W.; methodology, S.M., M.W., K.M., N.D., K.A. and W.Z.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M., K.M., N.D. and K.A.; data curation, S.M. and N.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. (all sections except Section 1.4) and M.W. (Section 1.4); writing—review and editing, S.M., M.W. and K.M.; visualization, S.M.; funding acquisition, M.W. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research, grant number 01LZ1802D. The APC was funded by Eberswalde University for Sustainable Development.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their gratitude to Bernd Cyffka, Florian Betz and Magdalena Lauermann (Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt) for their general support of the project, and to Ermek Baibagyshov (Naryn State University) and Erkinbek Satarov (former Mayor of Ak-Tal Village) for their support of the fieldwork. Special thanks to Mairambek uulu Yryskeldi, Nurmatbekov Zhyrgalbek, Tumar Marat kyzy, Tenizov Anarbek and Kurmanbekov Chubak (Naryn State University) for helping conduct the household interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Reid, W.V.C. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: General Synthesis: A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 1-59726-040-1. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, M.; Fairhead, J. Natural Resource Management: The Reproduction and Use of Environmental Misinformation in Guinea’s Forest-Savanna Transition Zone. IDS Bull. 1994, 25, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nasirdinov, S.; Chuikov, N.; Jumaliev, Z.; Tenizbaev, A.; Turdubaeva, C.; Biriukova, V.; Isenkulova, E. Kyrgyzstan: Brief Statistical Handbook, Bishkek, 2021. Available online: http://stat.kg/en/publications/kratkij-statisticheskij-spravochnik-kyrgyzstan/ (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Akimaliev, D.A.; Zaurov, D.E.; Eisenman, S.W. The Geography, Climate and Vegetation of Kyrgyzstan. In Medicinal Plants of Central Asia: Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan; Eisenman, S.W., Zaurov, D.E., Struwe, L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-4614-3911-0. [Google Scholar]

- CIA. Kyrgyzstan—The World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/kyrgyzstan/ (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- World Bank. Kyrgyz Republic Livesock Sector Review: Embracing the New Challenges, 2007. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/8033 (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- CIA. The World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/kyrgyzstan/ (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Betz, F. Biogeomorphology from Space; Universitätsbibliothek Eichstätt-Ingolstadt: Eichstätt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elnura, Z. Review of the Existing Information, Policies and Proposed or Implemented Climate Change Measures in Kyrgyzstan. 2010. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/k9589e/k9589e10.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Scheuber, M.; Müller, U.; Köhl, M. Wald und Forstwirtschaft Kirgistans|Forests and Forestry in Kyrgyzstan. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 2000, 151, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, T.; Kelly-Quinn, M.; Aguiar, F.C.; Manolaki, P.; Bruno, D.; Bejarano, M.D.; Clerici, N.; Fernandes, M.R.; Franco, J.C.; Pettit, N.; et al. Global Overview of Ecosystem Services Provided by Riparian Vegetation. BioScience 2020, 70, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undeland, A. Kyrgyz Livestock Study: Pasture Management and Use, 2005. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/287119/ (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Tjaart, W.; van Veen, S. The Kyrgyz Sheep Herders at the Crossroads: Pastoral Development Network Papers 38d; Pastoral Development Network Series 38; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, E.; Kreutzmann, H. High mountain ecology and economy: Potential and constraints. In High Mountain Pastoralism in Northern Pakistan; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2000; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shigaeva, J.; Hagerman, S.; Zerriffi, H.; Hergarten, C.; Isaeva, A.; Mamadalieva, Z.; Foggin, M. Decentralizing Governance of Agropastoral Systems in Kyrgyzstan: An Assessment of Recent Pasture Reforms. Mt. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, J. Kyrgyzstan: Central Asia’s Island of Democracy? Routledge: Oxon, UK, 1999; ISBN 9781315079325. [Google Scholar]

- Mogilevskii, R.; Abdrazakova, N.; Bolotbekova, A.; Chalbasova, S.; Dzhumaeva, S.; Tilekeyev, K. The Outcomes of 25 Years of Agricultural Reforms in Kyrgyzstan; Discussion Paper, No. 162; Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies (IAMO): Halle (Saale), Germany, 2017; Available online: https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:gbv:3:2-69129 (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Ruppert, D.; Welp, M.; Spies, M.; Thevs, N. Farmers’ Perceptions of Tree Shelterbelts on Agricultural Land in Rural Kyrgyzstan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Welp, M. (Eds.) Stakeholder Dialogues in Natural Resources Management: Theory and Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 9783540369172. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, K.; Ehrenwirth, M.; Missall, S.; Degembaeva, N.; Akmatov, K.; Zörner, W. Energy Profiling of a High-Altitude Kyrgyz Community: Challenges and Motivations to Preserve Floodplain Ecosystems Based on Household Survey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K. ÖkoFlussPlan: Start of Construction Works For “Real Lab” in Kyrgyzstan to Showcase Use of Solar Energy and Sustainable Insulation Materials. Available online: https://www.bmbf-client.de/en/news/okoflussplan-start-construction-works-real-lab-kyrgyzstan-showcase-use-solar-energy-and (accessed on 27 June 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).