Abstract

In contrast with many other sectors of the Russian economy, there is low market concentration in the forest industry and, consequently, a large number of relatively small enterprises scattered throughout the world’s largest country. In many cases, logging or woodworking companies are the only or key employers in sparsely populated areas, making them important sources of the social and economic stability of small towns and rural settlements. In 2022, Russian forest companies faced dramatic barriers to international trade, which led to the suspension of production with the risk of further layoffs. Thus, the issue of social and economic importance of the forest business in Russia has gained additional sounding. This paper aims to estimate the decline in revenues and the number of employees in forestry companies in Asian Russia because of sanctions. Based on corporate accounting reports, we have generated a dataset covering 4675 forest industry companies in Asian Russia. We use quantile regression to estimate the impact of the number of employees on revenue. All companies were divided into quartiles by revenue and into 6 groups by type of economic activity. A significant differentiation of the return on the number of employees depending on the type of activity and the volume of firms’ revenues was found. Estimates of potential losses of companies during labor force reduction were obtained, which would be 1.2%–3.6% of revenue for a company from Q1, 2.2%–6.6% of revenue for Q2 and 2.7%–8.1% of revenue for Q3. The results clearly demonstrate that forest companies might be very interested in retaining a workforce, even if an opportunistic drop in product demand creates a financial shortfall. Policy makers should take this into account when shaping instruments to support the industry.

1. Introduction

1.1. Micro-Level Analysis of the Russian Forest Industry: A Literature Review

The Russian timber industry successfully survived the COVID-19 crisis even though the lockdowns in major timber-producing countries have created a shortage of wood products on the world market [1,2,3]. At the same time, taking advantage of growing global demand for packaging and wooden constructions, the industry was able to set a new export record of $12.5 million in 2021. Another reason for the increase in logging and timber exports in 2021 was the anticipation of the state-announced ban on the export of unprocessed timber in January 2022. This public policy measure was introduced as part of the Russian President’s directive to decriminalize the timber industry and to combat illegal logging [4]. According to estimates by WWF and the World Bank, the Russian budget loses 13–30 billion rubles annually from illegal cuts [5]. The export ban should have had an obvious positive long-term effect in the form of incentives for the creation of facilities for deep processing of wood and more responsible forest management. However, industry representatives expressed concern that in the short term it might affect around 4000 timber organizations and could cause the shutdown of small and medium-sized logging companies [6,7].

At the beginning of the 2022 the Russian wood producers faced new challenges. The ban on imports of Russian timber products by primarily European countries has made the development of an export-oriented strategy for the industry even more urgent. Extensive trade restrictions cause structural changes in the Russian timber industry, affecting the timber production and supply chains. These shifts necessitate a comprehensive study on the market structure of timber producers in Russia. Especially considering that there is still scarce literature on the subject.

Most studies of the Russian forest industry analyze the role of Russian forests as a tool to mitigate the effects of the global climate change [8,9,10], the efficiency of forest management practices [11,12,13,14,15], the comparative advantages in wood products trade [16], the spatial heterogeneity in the timber industry [17,18], specific issues of the timber sector in some particular regions [19,20,21], etc. Due to limited data availability [22], microlevel research on Russian forest economics is occasional.

Several studies are devoted to Priority Investment Projects in the field of forest development (PIPs) in Russia. Since 2007, this public-private partnership initiative has become the main driver of the Russian timber industry. Investors are required to build or modernize woodworking enterprises in exchange for preferential terms for leasing forest land. Such measures of state support as provision of logging areas without an auction and preferential rent for forest areas during the entire payback period of the project have demonstrated the greatest effectiveness [23,24]. At the same time, a number of PIPs were either not implemented or have caused significant damage to the local ecosystem [25,26]. The logit regression modelling showed that the probability of successful implementation of investment projects is determined by several factors, those being revenue, number of employees, cost of fixed assets, profitability and the connection of the enterprise with foreign capital [27].

Study of the dynamics of corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices of forest companies in the Northwestern regions of Russia [28] shows that CSR in Russia is mainly developed in large forestry companies that have adopted the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification policy. However, the scale of violations of FSC standards does not significantly correlate with the scale of companies [14].

The behavioral pattern of tax evasion is not related to the scale of the business. At the same time, there is a strong correlation between the frequency of tax evasion attempts and the scores on the criteria that the Russian tax authorities consider as the basis for audit [29]. It was also shown that the level of collection of value-added tax (VAT) in the timber industry in Russia is 6 times lower than in the Scandinavian countries. Despite the growth of business activity of woodworking enterprises in 2012–2018, VAT revenues were, on average, negative due to significant amounts of unjustified tax refunds [30].

1.2. Imperfect Competition and Spatial Heterogeneity in the Russian Timber Industry

In Russia, the logging and timber industry operate in a monopolistic competition market. There are several large holdings and a lot of small companies. Even the top five firms by the logging volumes accumulates only 13.2% of all harvests (Table 1).

Table 1.

The top-five logging companies in Russia, 2020.

Despite the high number of companies, the spatial concentration of logging activities is still evident. The highest volumes are traditionally logged in the regions of Northwestern Russia (Arkhangelsk Oblast, Karelia Republic, Komi Republic, Vologda Oblast), as well as in Siberia (Irkutsk Oblast, Krasnoyarsk Krai). These two macroregions are the leaders of Russian timber industry due to the resource abundance and proximity to the main markets—Scandinavia and China, respectively [17].

In this paper, we focus on Asian Russia, which involves 21 Russian regions located east of the Ural Mountains and forming three federal districts: Ural, Siberian and Far Eastern. This part of Russia holds almost three quarters of the national timber reserves (Table 2).

Table 2.

The forest growing stock and cuts in Asian and European parts of Russia.

Among them, 14% of Russian forest growing stock are in the Krasnoyarsk Krai and 11% each in the Irkutsk Oblast and the Sakha Republic. However, a significant portion of these forests are in the northern hard-to-reach areas. They are unsuitable for logging, but in recent years have been intensively affected by forest fires [33,34].

The Irkutsk Oblast and Krasnoyarsk Krai are also national leaders in timber harvesting holding shares of 14.5% and 11%, respectively. Nevertheless, the manufacture of products with high value added is weak, due to the small scale of the domestic market, transport distance from the main areas of concentration of the population and economy, and the high demand for unprocessed timber from Asian countries [17]. As a result, the intensity of woodworking industry in Asian Russia is much lower than in the European part of the country, and its share of in the total volume of wood production decreases as the value-added of manufactured products grows up (Table 3).

Table 3.

The production volumes of wood commodities in Asian Russia, 2021.

1.3. Social Role of Forest Industry in Asian Russia under Sanctions

The economic contribution of timber sector has several dimensions, those being consumer goods, energy source, ecosystem services, products of intermediate consumption in other branches such as construction or transport, etc. [35]. In this paper we focus on the social role of the forest products manufactures in Russia, as such companies are important and often non-alternative employers for many remote communities. However, estimates of the number of people employed in the forest industry vary quite considerably. A joint study by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO) showed that about 33 million people worldwide were employed in the forestry sector between 2017 and 2019 [36]. Meanwhile, Li et al. [35] stated that the global forest sector directly employed more than 18.2 mln people and supported more than 45.1 mln jobs through direct, indirect and induced impacts.

Regardless, social function of timber industry is extremely important for Russia and its Asian part, where only 37 million people live in an area comparable to the size of the USA or Canada. Logging and processing companies employ at least 430,000 people in regions of Asian Russia, mostly in places where there are no other jobs. Thus, the social significance of the sector for the development of the entire vast macro-region cannot be overestimated.

The current sanctions against Russian exports of timber products may have a negative impact on the forest companies. The squeeze in both export and domestic demand during 2022 has already led to the suspension or reduction in production for some types of timber products, such as plywood [37]. This could provoke layoffs or the spread of various hidden unemployment practices, such as bonus cuts, pay cuts, part-time jobs, and unpaid vacations. Consequently, production shutdowns and layoffs will inevitably affect companies’ financial results in 2022 and beyond.

This study fills a gap in estimates of the economic and social impact of sanctions on Russian forest companies, using data on the relationship of labor and company revenues. We address two main research questions: (1) What are the quantitative estimates for the impact of the employee numbers on revenue in forestry companies in Asian Russia? (2) What economic losses could Asian Russian forest companies suffer due to current sanctions against Russian products?

In this paper, we focus on the indicators of economic activity of timber industry companies in Asian Russia. Given EU trade restrictions on Russian wood, timber business from Siberia and the Russian Far East appear to be in a slightly better position than firms from the Northwest, which main trade partners are European customers. Nevertheless, trade barriers coupled with the increased burden on transport networks, still create certain risks for companies in Asian Russia, as well.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the characteristics of the dataset of forestry companies in Asian Russia and suggests the modeling strategy used in the paper. Section 3 contains the results of an assessment of the impact of the number of employees on company revenues and estimates of companies’ losses because of workforce reductions during the current crisis in the Russian forest industry. Section 4 summarizes the main conclusion of the study and discusses the prospects for the Russian timber industry in the short term.

2. Materials and Methods

We have collected information on 9081 forestry companies registered on the territory of Asian Russia, as of 2021. We used the “Transparent business” service of the Federal Tax Service [38] and the Kontur.Focus database [36], which allows access to the financial reporting on Russian business entities. After omitting the companies with missing or outdated data, 4675 companies form a database that contains information on the legal status, main activities, average number of employees, revenue and net profit, authorized capital, date of registration, information on the owners, information on lawsuits, government contracts and procurement. All firms can be clustered by their main activity code determined by the companies on their own for tax purposes according to the Russian national classifier of economic activities (OKVED2). There is a common classification problem where an enterprise may also have several additional economic activity codes. For example, if a company is a large producer of lumber, it usually also carries out intensive logging. In these cases, it is quite difficult to clearly classify an enterprise. Table 4 reflects the classification of Asian Russian forest enterprises by main activity and the size of business. As a characteristic feature of the company’s scale of activity, we use revenue in accordance with the classification of small and medium-sized businesses adopted in Russia [39].

Table 4.

Forest companies in Asian Russia by type of activity and revenue, 2021.

We use quantile regression to analyze the relationship between number of employees and revenue for companies of different sizes. While ordinary least squares (OLS) produce estimates for a firm with an average revenue value, quantile regression allows the same for any percentile of the revenue distribution. In order to calculate the estimates quantile regression uses least absolute deviation (LAD), which is the statistical optimization technique firstly introduced by R. J. Boscovich [40]. Though the intuition behind this method is similar to that of minimum sum of squared residuals used in OLS, there is no analytical method of expressing the LAD and therefore it requires the use of linear programming methods [41,42].

The idea of quantile regression was introduced by R. Koenker [43,44]. If there is a dependent variable and an independent variable , it can be shown that the quantile of order tau ( in the distribution of depends linearly on the explanatory variable :

where is a value such that and are the regression coefficients, which are estimated by the minimization of the absolute deviations:

where is the penalty value depending on the ratio of the predicted and the actual value of :

In this paper, the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of the company’s revenue, and the explanatory variable is the average number of employees. It should be noted that according to the reporting requirements for companies, the average headcount includes only employees who are registered under employment contracts. If employees work on a part-time employment, their number is calculated in proportion to the hours worked. For calculating the quantile regression coefficients, we used quantreg package [45] for R [46].

3. Results

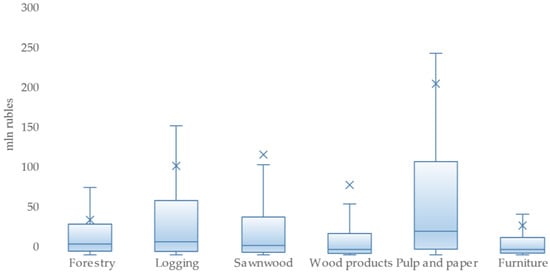

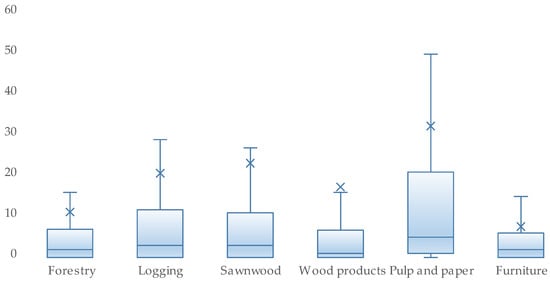

The revenue and employees’ distributions for the firms of different activities can be seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2 (for a clearer view the outliers were excluded from the figures).

Figure 1.

The revenue distributions for the Asian Russian forest companies by the economic activity type, mln rubles.

Figure 2.

The number of employees distributions for the Asian Russian forest companies by the economic activity type.

Both Figure 1 and Figure 2 clearly indicate asymmetric distributions of variables with large numbers of outliers. For all types of activities, the mean values of revenue and number of employees are much higher than the median. This illustrates the main advantages of quantile regression over the OLS, as the quantile regression is robust to outliers, and does not require the distribution of dependent variable or the errors to be normal [47].

Another point is that the average number of employees might be underestimated in the reports of timber enterprises. Most of the Asian Russian companies in all forestry sectors reported that they employ less than 10 employees in 2021. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing are the largest sector of the Russian economy in terms of the share of employment in the informal sector after retail trade: according to Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (Rosstat), its share has fallen from 28.7% in 2009 to 16% in 2021 [48]. Although there are no detailed data on informal labor in the forestry sector, it is likely to be most widespread in the logging sector. In some regions of Russia, it may account for more than 30% of the employment in timber harvesting [49].

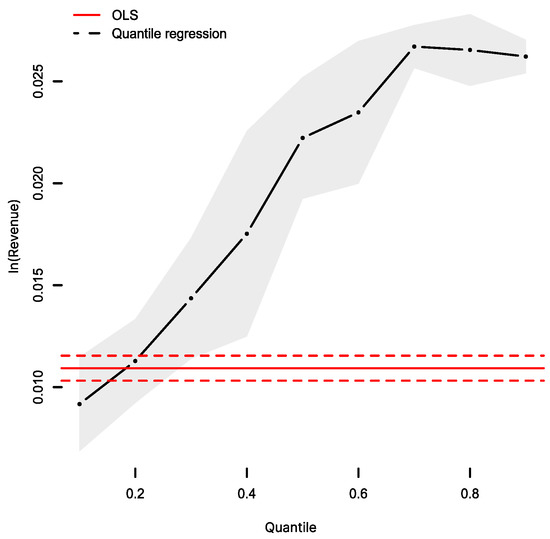

The comparison between OLS and quantile regression estimates for the pooled sample of all forestry companies in Asian Russia is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The slope coefficients for the different quantiles of revenue distribution for Asian Russian timber enterprises. The red dotted line as well as the grey area represent the confidence intervals.

The black dots on the Figure 3 reflect the slope coefficients for each decile of revenue distribution. These coefficients vary greatly across the quantiles and, starting from the second decile, exceed the OLS estimate. In our case, this is the evidence that OLS obtains lower estimates than the LAD optimization technique, including median regression.

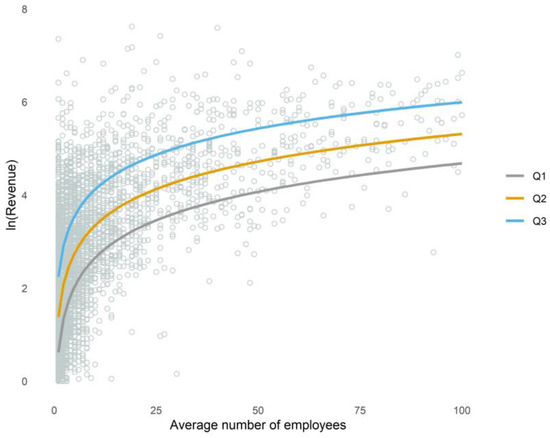

Based on the results shown in Figure 3, to further estimate the effect of an additional employee for companies of different sizes, we divided the revenue distribution into quartiles. This division seems optimal in the form of a relatively small number of models that describe the most important patterns in the distribution (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The scatterplot for the logarithm of revenue and the average number of employees in Asian Russian forest companies.

The modelling results for the seven samples divided by the main economic activity type are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

OLS and quantile regression results for Asian Russian companies by activity type.

The resulting estimates for each model are positive and appear to be adequate, as almost all of them are significant. As shown earlier in Figure 3, the OLS slope coefficients are generally lower than the estimates obtained for the three quartiles.

For all samples, the marginal effect of an additional worker increases as the firm’s revenue grows up. For instance, model 1 shows that each employee in forest sector contributes 1.2%, 2.2% and 2.7% of revenue for a firm at the Q1, Q2 and Q3 level, respectively (see Table 5). Estimates also differ by type of economic activity. The highest return on each employee was found in the furniture industry. Even the company with median revenue gains 5.9% of its revenue from an additional worker. The largest gap in estimates between quartiles is observed for the wood products industry. Each additional employee brings a small company (Q1 by revenue) only 0.8% of revenue, while for a large company (Q3 by revenue) the marginal effect is 2.66%. This can be explained by the high heterogeneity of the sample, as this category includes both microenterprises specializing on wooden accessories and large plants producing plywood, fiberboard, or building structures.

As it was mentioned before, these estimates can be used to assess the potential financial losses of companies in case of rising unemployment in the industry. The timber sector is at high risk of unemployment for a few reasons. First, significant export restrictions, the main one being the fifth package of EU sanctions, which imposes a ban on the import of a wide range of Russian timber products into the EU [50]. For many Russian companies focused on trade with European nations, this has become a difficult challenge to overcome, which requires building new supply chains to the domestic market or to other countries. In the period of logistics restructuring, many companies are experiencing a decrease in production capacity utilization. In March 2022, the birch plywood mill Sveza Ural sent 15% of its employees to downtime [51]. However, already in June the company continued its work [52]. Moreover, difficulties in repairing and purchasing sanctioned machinery also reduce the possibility of hiring new staff that will inevitably reduce the total employment in the nearest future.

Another risk is associated with the withdrawal of foreign owners from Russian businesses. Many international corporations, such as IKEA, International Paper, Mondi, were major employers in Russia. IKEA laid off 10,000 employees in Russia [53]. Most of them were employed in retail, but some of them also worked in IKEA-owned contractors. The furniture factory Ikea Industry Tikhvin has retained only 500 employees out of 1000 who work on a one-week break [54]. Finnish lumber producers in Leningrad Oblast Metsä Svir and Metsä Forest laid off 35 and 25 people, respectively, in August 2022, accounting for 33% and 20% of the total workforce [55]. It is likely that after the change of ownership, the laid-off workers will be hired again, but still this process creates temporary tensions in the labor market. Single-industry towns, i.e., settlements in which the main employer is a logging or wood-processing enterprise, are particularly vulnerable to rising unemployment and social tensions [56]. According to the Center for Strategic Research, 20 out of 45 timber companies in single-industry towns were forced to look for new markets in the first half of 2022 [57].

Asian Russian companies are in a better situation because they were more focused on trade with China and other Asian countries [16]. Nevertheless, they are experiencing certain problems, as well. These are reciprocal trade restrictions with Japan and competition for supplies with other Russian timber companies, which are trying to redirect their sales to Asian countries. The strengthening of the ruble and the rising cost of transportation significantly reduce the profitability of the business. Regions, such as Primorsky Krai, where valuable species of wood (oak, ash, etc.) grow, are in a more favorable situation. At the same time, regions dominated by conifers and birch, such as Khabarovsk Krai, are forced to reduce production [58].

All these new factors are combined with the forestry staff reduction, which began back in early 2022, due to the ban on the export of unprocessed timber. In January 2022, the average number of employees of forestry companies in the Far East decreased by 4.3% compared to January 2021 [59].

At the time of writing the manuscript there is no detailed data on the current situation in the labor market by industry. Apparently, the only attempt to estimate unemployment by industry was the May 2022 report of the Center for Strategic Research, non-profit organization, one of the founders of which is the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation [60]. According to this report, the greatest increase in unemployment is likely to occur at relatively large enterprises in regions with a pronounced industrial structure of the economy. The timber and woodworking industry were included in top five sectors of Russian economy with a high risk of unemployment. For the whole forest sector, potential job losses were estimated at 86,000. Table 6 shows the number of workers in the timber industry of the Asian part of Russia.

Table 6.

The number of people employed in forest sector in Russia, Asian Russia and corresponding federal districts in 2021 by the type of economic activity, thousands.

Assuming that the reduction in labor force will be in the same proportion, then the loss of companies in Asian Russia will be 24,176 employees. With the total number of timber enterprises in our database being 9081, each firm might have an average reduction of about 2.66 employees. Combining this with the slope coefficients shown in Table 5 for Model 1, we obtain interval estimates for the case of a reduction in the average number of employees from 1 to 3 people in 2022 (Table 7).

Table 7.

The estimates of potential losses for three types of Asian Russian forest companies, divided by revenue volume.

The obtained estimates show that the potential losses of revenues caused by firing staff seem to be quite significant for the companies of the forest sector, which is already the least profitable of the resource industries of the Russian economy. This is a key finding to understand the anti-crisis strategy of forest business in Asian Russia, that the companies should do their best to save workplaces by using other methods to reduce costs in the short term.

An analysis of the pandemic crisis consequences showed that the Russian labor market adapted to the suspension of production mainly by slowing the recruitment of new workers while reducing the retirement of those already employed [61]. Traditional mechanisms for maintaining sustainability in the Russian labor market, such as wage cuts, transfer to part-time work, forced vacations were also actively used [62]. Business was not interested in the loss of human capital, understanding the temporary nature of the restrictions and preparing for the subsequent recovery of economic activity [61]. It is quite possible that the mechanisms that showed a high efficiency in the pandemic will be reproduced now. This will avoid a massive spike in unemployment.

4. Discussions and Conclusions

Given the exceptional scale of the sanctions imposed on the Russian economy, it is difficult to compare our results with other studies. It is obvious that the decrease in the intensity of Russia’s economic ties with Europe, the United States, Great Britain, and Japan opens opportunities for more intensive trade with countries that have not joined the restrictions. The example of the sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014 showed that they significantly contributed to an increase in trade between Russia and China, and this trend will undoubtedly hold [63]. In addition, the analysis of overnight lighting showed that there was a decrease in business activity in Russia at the beginning of the imposition of sanctions in 2014, but subsequently the economy adapted and the impact of sanctions on business activity declined [64]. These results are consistent with what is currently happening. After short-term shocks in the form of the suspension of production, the timber industry is gradually recovering and redirecting to other markets.

This paper contributes to the literature about Russian forestry in several ways. Following Labunets and Maiburov [29], we analyze the company-level reporting statistics of timber companies in Russia. The main result of this study is a database of 9081 forestry companies operating in the Asian part of Russia. The findings of this paper are only the first step in the comprehensive research of the forest business in Asian Russia at the micro level. Given the fact that there is little literature on forestry companies in Russia, this topic seems to be quite relevant.

Asian Russia is an extremely important region for the development of the timber industry. Even though only 44% of Russian timber and logging industry employees work there, it produces 53% of all Russian sawn timber, and its wood reserves amount to 74.7% of the national level. At the same time, the volume of high-value-added products in Asian Russia is still limited, due to the small size of the domestic market and the conjuncture of demand from bordering countries [17]. Meanwhile, the decline in foreign trade with the European Union creates additional development opportunities for the regions of Asian Russia. First, it makes the territories of Asian Russia more attractive for investors compared to the European part of the country. In addition, India, which banned plastic packaging from 1 July 2022 [65], and the United Arab Emirates, with high demand for building structures [66], could become promising new markets for Asian Russian timber products.

The timber sector in Russia is one of the few industries whose structure is not oligopolistic. The analysis of the distribution of revenues and the number of employees showed significant heterogeneity of forest business in Russia. 89% of all the companies we studied are micro firms with revenues of up to 120 million rubles or $1.63 million, given the average annual exchange rate for 2021 (see Table 4).

The features of the distribution also explain the choice of the method for studying the impact of the number of employees on the company’s revenue. Theoretical insights indicate that estimates using quantile regression have a number of advantages over widespread OLS, such as absence of requirements to the distribution of the dependent variable and robustness to outliers [43,47]. Section 3 shows that the estimates obtained with OLS are undervalued compared to quantile regression. For all activities in the forestry sector, the OLS estimates were lower even than the estimates for the first quartile obtained with the LAD. This result is consistent with previous research and confirms that the OLS estimates obtained for the average company are not quite adequate for samples with a large number of outliers [67,68].

Using quantile regression, we obtained estimates of workers’ contribution to company revenues for the key six sectors of the timber industry: forestry, logging, manufacture of sawnwood, wood products, pulp and paper, furniture. It was shown that the employee’s contribution also differed according to the firm’s revenue. For the pooled sample, the gap between the company with revenue at the first quartile level and the third quartile level was more than 2 times: from 1.2% to 2.7% of revenue.

It should be noted that the model considers only an abstract average timber industry worker. A brief characteristic of an employee of a forestry company in Russia can be obtained from resumes for job applications available on public websites. For example, at the end of 2019 the vast majority of applicants were men (86%), and only 14% were women [69]. The distribution of resumes by age is the following: 31% were 26–35 years old, 34% were 36–45 years old, and 18% were 46–55 years old. Also, most of the job seekers had higher education (64%) or specialized secondary education (20%), and professional experience of more than six years (79%). However, detailed data on the sex and age structure of employees of forestry companies is not available and therefore was not considered in the analysis.

Even though the whole timber industry contributes less than 2% of Russia’s GDP, forestry companies are extremely important employers in rural areas and small towns. This paper provides estimates of the potential negative effects on the financial performance of forestry companies in Asian Russia from possible labor force reductions resulting from international restrictions on trade with Russia. For a company with revenue at the first quartile level, the loss will be 1.2%–3.6% of revenue, at the Q2 level it will be 2.2%–6.6% of revenue and at the Q3 level it will be 2.7%–8.1% of revenue.

In addition to the sanctions and their consequences, there are other risks to the decline of employment in the forest industry that were not considered in the analysis. For example, an important long-term risk is global warming, which has a negative impact on logging prospects. For example, the leading logging regions of Russia such as Krasnoyarsk Krai and Irkutsk Oblast have already experienced a gradual reduction in the logging season duration [9]. On the contrary, the need to strengthen the fight against such negative effects of climate change as forest fires [33] and insect pest infestations [70,71] requires hiring additional staff and may stimulate employment growth in the forestry sector.

It is important to note that our estimates are based on the unemployment forecast from the Center for Strategic Research, which was made in May 2022. However, given the high uncertainty risks for the Russian economy in 2022, the general forecasts of macroeconomic indicators are rather quickly outdated and revised. In spring, expectations for key indicators of the Russian economy, such as GDP, the ruble exchange rate, inflation, and unemployment were much more pessimistic than at the end of 2022.

In September, the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation improved its unemployment forecast for the end of 2022 to 4.2% from the 6.7% in its May forecast [72]. This estimate is six percentage points lower than last year’s value. A slight increase to 4.4% is expected in 2023, followed by a gradual decline to 4.1%. In addition, measures to support the labor market have been developed. It is planned to compensate part of wages in case of part-time employment, transfer to another employer and retraining of jobseekers.

Another point is that the Russian economy has proven to be much stronger and more resistant to sanctions than many had assumed. The active implementation of state support measures, such as extending the terms of investment projects, preferential loans to cover the deficit of working capital, the removal of restrictions on the purchase of imported equipment and customs duties allows to expect a gradual recovery of the timber industry in 2023 [73]. Russia is a very important player for the world’s timber supply chains and cannot be excluded from them. This is confirmed by numerous evidence of continuing trade relations with other countries despite formal restrictions. For instance, wood products remain one of the leaders in trade between Russia and the USA with 1294 shipments in the six-month period since 24 February 2022 [74]. One of the reasons is that most of the American wooden classroom furniture and home flooring is made from Russian birch. Often the shipment is made through third countries, which consequently leads to higher prices for the end consumer [75].

Thus, we characterized the market of forestry enterprises in Asian Russia, assessed the impact of the average number of employees on revenue, and obtained estimates of the companies’ losses from the possible negative effects of sanctions. The results clearly demonstrate that forest companies should be very interested in retaining a workforce, even if an opportunistic drop in product demand creates a financial shortfall. The loss of workers engaged in quite specific labor in places remote from large cities can create serious difficulties for the existence of the business. On the other hand, layoffs of employees will also lead to employment problems. The policymakers should take these considerations into account when forming support mechanisms for forest enterprises. One of the most promising areas of further research could be the study of regional differences. The characteristics of companies can vary significantly depending on the territory. For example, in large logging regions, such as Krasnoyarsk Krai, Irkutsk Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai, estimates of employees’ contribution to revenues may be higher than for regions with smaller volume of forest industry activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.P.; methodology, A.I.P. and R.V.G.; software, R.V.G. and A.I.P.; formal analysis, R.V.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.V.G.; writing—review and editing, R.V.G. and A.I.P.; visualization, R.V.G.; supervision, A.I.P.; project administration, A.I.P.; funding acquisition, A.I.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation within the framework of grant for large scientific projects in priority directions of scientific and technological development no. 075-15-2020-804/13.1902.21.0016 dated 2 October 2020 entitled “Socioeconomic development of Asian Russia based on the synergy of transport accessibility, system knowledge about natural resource potential, expanding space of inter-regional interactions”.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Nelly Kolyan for the valuable help in data collection. The authors want to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, which helped to significantly expand the text on the social role of the Russian forest companies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stanturf, J.A.; Mansuy, N. COVID-19 and Forests in Canada and the United States: Initial Assessment and Beyond. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 666960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Kaimowitz, D.; Jensen, S.; Feder, S. Coronavirus, Macroeconomy, and Forests: What Likely Impacts? For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kooten, G.C.; Schmitz, A. COVID-19 Impacts on U.S. Lumber Markets. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 135, 102665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List of Instructions Based on the Results of the Meeting on the Development and Decriminalization of the Forestry Complex. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/assignments/orders/64379 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- FAO. The Russian Federation Forest Sector: Outlook Study to 2030; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; ISBN 978-92-5-107309-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stoilova, A.S. Impact of the Prospective Roundwood Export Ban on Russian Timber Production. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 14, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russian Forest Federal Agency: The Ban on Exporting Unprocessed Logs May Affect the Activity of 4000 Organizations. Available online: https://whatwood.ru/english/russian-forest-federal-agancy-the-ban-on-exporting-unprocessed-logs-may-affect-the-activity-of-4-000-organizations/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Leskinen, P.; Lindner, M.; Verkerk, P.J.; Nabuurs, G.J.; Van Brusselen, J.; Kulikova, E.; Hassegawa, M.; Lerink, B. (Eds.) Russian Forests and Climate Change. What Science Can Tell Us; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chugunkova, A.V.; Pyzhev, A.I. Impacts of Global Climate Change on Duration of Logging Season in Siberian Boreal Forests. Forests 2020, 11, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaganov, E.A.; Porfiryev, B.N.; Shirov, A.A.; Kolpakov, A.Y.; Pyzhev, A.I. Assessment of the Contribution of Russian Forests to Climate Change Mitigation. Ekon. Reg. 2021, 17, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, D.; Jarlebring, N.Y.; Mustalahti, I.; Sotirov, M.; Kulikova, E.; Lopatin, E. The Forest Environmental Frontier in Russia: Between Sustainable Forest Management Discourses and “Wood Mining” Practice. Ambio 2021, 50, 2138–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyzhev, A.I. Impact of the Ownership Regime on Forest Use Efficiency: Cross-Country Analysis. J. Inst. Stud. 2019, 11, 182–193. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trishkin, M.; Lopatin, E.; Shmatkov, N.; Karjalainen, T. Assessment of Sustainability of Forest Management Practices on the Operational Level in Northwestern Russia—A Case Study from the Republic of Karelia. Scand. J. For. Res. 2017, 32, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trishkin, M.; Karjalainen, T.; Kangas, J. An Analysis of the Non-Conformities of Certified Companies Operating in Northwestern Russia. Forests 2019, 10, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Katkova, T.; Karvinen, S. Comparative Analysis of Forestry Economic Indicators of Russia and Finland. HSE Econ. J. 2018, 22, 294–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, R. Comparative Advantages of Russian Forest Products on the Global Market. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 119, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, R.V.; Pyzhev, A.I.; Yagolnitser, M.A. Drivers of Spatial Heterogeneity in the Russian Forest Sector: A Multiple Factor Analysis. Forests 2021, 12, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazyrina, I.; Zabelina, I.; Faleychik, L. Spatial Heterogeneity of «Green» Economy and Transaction Costs in Forestry. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 753, 082020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, N. Forest Complex of the Far East: Is There Groundwork for Future Development? ECO 2019, 5, 27–47. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazyrina, I.P.; Yakovleva, K.A.; Zhadina, K.A. Social and Economic Effectiveness of the Forest Use in the Russian Regions. Regionalistica 2015, 2, 18–33. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, N. Transformation of the Forest Complex during the Years of Russian Reforms: The Far Eastern Viewpoint. Spat. Econ. 2017, 3, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyzhev, A.I.; Gordeev, R.V.; Vaganov, E.A. Reliability and Integrity of Forest Sector Statistics—A Major Constraint to Effective Forest Policy in Russia. Sustainability 2020, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapo, V.F. Efficiency of Investment Stimulation Methods in a Timber Industry Complex: An Econometric Research. Appl. Econom. 2014, 1, 30–50. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lapo, V.F. Regions’ Competition for Investment Projects in Forest Development. Spat. Econ. 2014, 2, 75–92. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kolesnikova, A. The Effect of Prior Investment Projects Mechanism on the Development of Forest-industry Complex in the Siberian and the Far East Federal Districts. ECO 2015, 8, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazyrina, I.P.; Zabelina, I.A.; Klevakina, E.A. An Environmental Component of Economic Development: The Border Regions of Russia and China. EKO 2014, 6, 5–24. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivantsova, E.D.; Pyzhev, A.I. Factors of success of priority investment projects in the sphere of forest exploitation in Russia: Econometric analysis. Russ. J. Econ. Law 2022, 16, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, A.-M. Forest Companies, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Company Stakeholders in the Russian Forest Sector. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 31, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labunets, I.E.; Mayburov, I.A. The Impact of the Size of Enterprises on Tax Evasion in the Forestry Industry of Russia. J. Tax Reform 2022, 8, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labunets, I.E.; Mayburov, I.A. Tax control of vat refund in Russia and in the Scandinavian countries on the example of timber industries. Tyumen State Univ. Herald. Soc. Econ. Law Res. 2020, 6, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslesinforg. Roslesinforg Identified Leaders among Forestry Companies. Available online: https://roslesinforg.ru/news/all/3892/ (accessed on 27 October 2022).

- Federal State Statistics Service of Russia. Edinaya Mezhvedomstvennaya Informatsionno—Spravochnaya Systema—EMISS. (Unified Interagency Information and Statistical System. State Statistics). Available online: https://www.fedstat.ru/ (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Loupian, E.A.; Bartalev, S.A.; Balashov, I.V.; Egorov, V.A.; Ershov, D.V.; Kobets, D.A.; Senko, K.S.; Stytsenko, F.V.; Sychugov, I.G. Satellite Monitoring of Forest Fires in the 21st Century in the Territory of the Russian Federation (Facts and Figures Based on Active Fires Detection). Sovrem. Probl. Distantsionnogo Zondirovaniya Zemli Kosm. 2017, 14, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupian, E.; Balashov, I.V.; Bartalev, S.A.; Burtsev, M.A.; Dmitriev, V.V.; Senko, K.S.; Krasheninnikova, Y.S. Forest Fires in Russia: Specifics of the 2019 Fire Season. Sovrem. Probl. Distantsionnogo Zondirovaniya Zemli Kosm. 2019, 16, 356–363. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mei, B.; Linhares-Juvenal, T. The Economic Contribution of the World’s Forest Sector. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 100, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippe, R.S.; Schweinle, J.; Cui, S.; Gurbuzer, Y.; Katajamäki, W.; Villarreal-Fuentes, M.; Walter, S. Contribution of the Forest Sector to Total Employment in National Economies: Estimating the Number of People Employed in the Forest Sector; FAO: Rome, Italy; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-136996-8. [Google Scholar]

- The World’s Largest Plywood Producer Reported Underutilization of up to 80%. Available online: https://www.rbc.ru/business/23/06/2022/62b4284d9a7947015ef6a86a (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Transparent Business. Available online: https://pb.nalog.ru/index.html (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- The Federal Law № 209-FZ On the Development of Small and Medium Entrepreneurship in the Russian Federation. Available online: http://kremlin.ru/acts/bank/25971 (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Maire, C.; Boscovich, R.G. De Litteraria Expeditione per Pontificiam Ditionem ad Dimetiendos duos Meridiani Gradus et Corrigendam Mappam Geographicam, Iussu et Auspiciis Benedicti XIV Pont. Max; In Typographio Palladis excudebant N. et M. Palearini: Rome, Italy, 1755. [Google Scholar]

- Barrodale, I.; Roberts, F.D.K. An Improved Algorithm for Discrete l1 Linear Approximation. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1973, 10, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowsky, G.O. A New Descent Algorithm for the Least Absolute Value Regression Problem: A New Descent Algorithm for the Least Absolute Value. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 1981, 10, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R. Quantile Regression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-521-60827-5. [Google Scholar]

- Koenker, R.; Chernozhukov, V.; He, X.; Peng, L. (Eds.) Handbook of Quantile Regression; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-12025-6. [Google Scholar]

- Quantreg: Quantile Regression. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=quantreg (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- John, O. Robustness of Quantile Regression to Outliers. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2015, 3, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal State Statistics Service of Russia. Labor Force, Employment, and Unemployment in Russia; Rosstat: Mocow, Russia, 2022.

- Informal Employment in the Logging Industry in the Region Decreased by 40%. Available online: http://gorodkirov.ru/news/neformalnaya-zanyatost-v-lesozagotovke-po-regionu-snizilas-na-40-20191129-2145/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Council Regulation (EU) 2022/576 of 8 April 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 833/2014 Concerning Restrictive Measures in View of Russia’s Actions Destabilising the Situation in Ukraine, Volume 111. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/576/oj (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Downtime is Such Forest. Available online: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5284003 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- The Sveza Ural Plant Resumed Production. Available online: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5422503 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Reuters. IKEA Lets around 10,000 Staff Go in Russia—AFP. Reuters 2022. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/retail-consumer/ikea-lets-around-10000-staff-go-russia-afp-2022-10-13/ (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Lumberjack Will Be Sent Home. Available online: https://vedomosti-spb.ru/economics/articles/2022/09/15/941050-lesopererabotku-otpravyat-domoi (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- There Will Be No Mass Layoffs in the Timber Industry in the Leningrad Oblast. Available online: https://newprospect.ru/news/aktualno-segodnya/massovykh-sokrashcheniy-v-lesopromyshlennom-komplekse-lenoblasti-ne-budet/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Pyzheva, Y.I. Sustainable Development of Single-Industry Towns in Siberia and the Russian Far East: What Is the Price of Regional Economic Growth? J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 13, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Strategic Research City-Forming Enterprises of Single-Industry Towns: Mechanisms of Adaptation to the Risks of the First Half of 2022. Available online: https://www.csr.ru/ru/publications/gradoobrazuyushchie-predpriyatiya-monogorodov-mekhanizmy-adaptatsii-k-riskam-pervoy-poloviny-2022-goda/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- A Strong Ruble Broke the Business of Timber Producers. Available online: https://konkurent.ru/article/51234 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- The Timber Industry in the Far East Has Begun to Lay Off Workers. Available online: https://forestcomplex.ru/forestry/v-lesnoj-otrasli-dalnego-vostoka-nachalis-sokrashheniya/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Center for Strategic Research. Regional Labor Markets in the New Economic Conditions. Available online: https://www.csr.ru/ru/publications/regionalnye-rynki-truda-v-novykh-ekonomicheskikh-usloviyakh/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Gimpelson, V.E. Wages and labor market flows in times of the corona crisis. Vopr. Èkon. 2022, 2, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapeliushnikov, R.I. The anatomy of the corona crisis through the lens of the labor market adjustment. Vopr. Èkon. 2022, 2, 33–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, J. Sanctions as a Catalyst for Russia’s and China’s Balance of Trade: Business Opportunity. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, T. Economic Sanctions and Regional Differences: Evidence from Sanctions on Russia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of India. Ban on Single Use Plastic in India: Step towards Clean India, Green India; Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of India: New Delhi, India, 2022; 6p.

- Salama, M.; Hana, A. Sustainable Construction, Green Building Strategic Model. In Principles of Sustainable Project Management; Salama, M., Ed.; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-911396-85-7. [Google Scholar]

- Varin, S. Comparing the Predictive Performance of OLS and 7 Robust Linear Regression Estimators on a Real and Simulated Datasets. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2021, 5, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, I.; Yahaya, A. Analysis of Quantile Regression as Alternative to Ordinary Least Squares. Int. J. Adv. Stat. Probab. 2015, 3, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhilnikova, I. Supply and Demand in the Forest Industry Labor Market in 2019. Available online: https://hh.ru/article/26118 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Ivantsova, E.D.; Pyzhev, A.I.; Zander, E.V. Economic Consequences of Insect Pests Outbreaks in Boreal Forests: A Literature Review. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 12, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukhovolsky, V.; Kovalev, A.; Tarasova, O.; Modlinger, R.; Křenová, Z.; Mezei, P.; Škvarenina, J.; Rožnovský, J.; Korolyova, N.; Majdák, A.; et al. Wind Damage and Temperature Effect on Tree Mortality Caused by Ips Typographus L.: Phase Transition Model. Forests 2022, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation Forecast of Socio-Economic Development of the Russian Federation for 2023 and for the Planning Period 2024 and 2025. Available online: https://www.economy.gov.ru/material/directions/makroec/prognozy_socialno_ekonomicheskogo_razvitiya/prognoz_socialno_ekonomicheskogo_razvitiya_rossiyskoy_federacii_na_2023_god_i_na_planovyy_period_2024_i_2025_godov.html (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Export of the Vologda Region’s Timber Industry Products Is Planned to Be Restored in 2023. Available online: https://tass.ru/ekonomika/16295197 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Six Months into War, Russian Goods Still Flowing to US. AP News 2022. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-putin-biden-baltimore-only-on-ap-81a34ce2eecebe491f52ace380ce87fb (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- How Russian Timber Bypasses U.S. Sanctions by Way of Vietnam. Washington Post 2022. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/10/01/russia-sanctions-birch-wood-vietnam-china/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).