Abstract

The distribution of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker (Leiopicus medius) is restricted to mature deciduous forests with large trees, mainly oaks (Quercus spp.). Intensive forest management resulted in the loss of many suitable habitats, thus resulting in a decline in the population of this species. This study aimed to identify the parameters of foraging sites in the breeding season (April to June) and in the non-breeding season (other months). The research was conducted in the primeval oak-lime-hornbeam forest of the Białowieża National Park, where foraging woodpeckers were observed and detailed parameters of foraging sites were recorded. During the breeding season woodpeckers foraged primarily on European hornbeams (Carpinus betulus L.), but in non-breeding season the use of this tree species decreased by a factor of two, whereas the use of Norway spruces (Picea abies L.) increased more than twice. The most preferred tree species as a foraging site in both seasons was pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.). In the non-breeding season, woodpeckers foraged at sites located higher, and the foraging session was longer compared with the breeding season. In both seasons, woodpeckers preferred dead and large trees and prey gleaning from the tree surface was their dominant foraging technique. Our results confirmed the key role of oaks and large trees, but also revealed the importance of European hornbeams and Norway spruces as foraging sites for the Middle Spotted Woodpecker.

1. Introduction

The Middle Spotted Woodpecker (Leiopicus medius) is a non-migratory species distributed over large parts of Europe from eastern Spain to western Russia, and further in the Caucasus, northern Turkey, Asia Minor and Iran [1]. It is a habitat specialist, occurring in mature deciduous forests with large trees, especially oaks Quercus spp. [2,3]. In the 20th century, there was a significant decline in the population of this species due to intensive forest management resulting in the loss of suitable habitats. Now, the species is close to extinction or extinct in many parts of Europe [1,4,5,6]. Detailed knowledge of the foraging-site preferences of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker, which can potentially vary throughout the year, is one of the basic conditions for establishing an effective conservation strategy for this species. Although the foraging behavior of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker has been studied in Europe, including Poland [7,8,9,10], comparisons between different seasons in this respect are rare [11,12]. Moreover, little is known about the foraging habits of this woodpecker species in primeval forests. To our knowledge, only two published papers conducted in the Białowieża Forest mentioned the foraging of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker, but the information given there is limited to the contributions of dead trees and common aspen Populus tremula L. used by this species [13,14].

Białowieża National Park, where our research was conducted, protects the best-preserved natural European lowland forest, a remnant of the vast primeval forests that once covered most of the continent. The research conducted in this unique place allows us to observe organisms in their natural habitats and to better understand the evolution of various adaptations and behaviours of animals. Almost all European woodpecker species (potential competitors for food) nest here. The Middle Spotted Woodpecker, and the Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major, are the most common of them, reaching a density of up to 1.4 pairs/10 ha [15]. In this study, we investigated the selection of foraging sites by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker in primeval oak-lime-hornbeam stands in the Białowieża National Park in breeding and non-breeding seasons. We assumed that some trees or parts of trees provide more food than others and should therefore be targeted more often by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker, with foraging taking the longest time there. However, the decision to choose a feeding place may also be influenced by prey accessibility, which can be affected by, e.g., weather conditions, temperature, or time of day [16,17,18]. The risk of predation is also of great importance, therefore sites with high prey density but high predator pressure might be avoided [19,20]. Foraging site selection may also be influenced by the season, as food resources vary considerably throughout the year. For example, the abundance of spiders, including those living on the bark of trees (common woodpeckers’ prey), varies significantly during specific months of the year [21,22]. Seasonal changes in the abundance also affect many insects inhabiting oaks Quercus spp.–trees frequently used by Middle Spotted Woodpecker during foraging [23].

The primary objectives of our study were: (1) to characterise and compare foraging sites used during breeding and non-breeding seasons, (2) to indicate preferred trees in terms of their species, condition (dead or live) and dimensions (expressed as a trunk diameter at breast height) during foraging based on available resources.

We hypothesised that the Middle Spotted Woodpecker would prefer trees with large dimensions (i.e., large trunk diameter at breast height) over trees with small dimensions. We assumed that large trees are inhabited by a larger number of invertebrates compared with trees with smaller diameter trunks, as shown by some studies [24,25]. Furthermore, we expected that pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) would be particularly preferred, in line with the findings of other authors [1,8,9,12]. Oak trees reach considerable size, and their fissured bark provides habitat for many taxa of invertebrates [26,27]. We also predicted that the selection of sites by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker during foraging would be different in breeding and non-breeding seasons. Our hypothesis was based on the fact that both the habitat structure of the forest and food availability change significantly throughout the year. Reduced food resources during the non-breeding season in the temperate zone, mainly due to climatic conditions, force many non-migratory bird species, including woodpeckers, to change their foraging behaviour. They must look for new sites where they can find food, as the existing food resources are reduced or have disappeared altogether, and, in addition, harsh weather conditions make them less accessible. In winter, for example, thick snow cover on dead, downed trees or limbs prevents woodpeckers from feeding in these places, thus they must change their foraging behaviour and sites where they search for food [16,17]. Furthermore, we predicted that the difference in foraging site selection between the two analyzed seasons may also be a result of nestling feeding in the breeding period. The diet of nestlings may be different from the diet of adult birds. Pavlík [28] showed that leaf-eating Lepidoptera larvae are the basic food of nestlings of Great and Middle Spotted Woodpeckers, while those larvae constituted only a small part of the food of adult woodpeckers. Woodpeckers are therefore more likely to visit the canopy of live trees and thin branches with leaves (where these larvae are found) during the breeding season rather than in the non-breeding season, as shown by the study of Pettersson [12].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in the Białowieża Forest, a large forest complex located on the Polish-Belarusian border. A study area of approximately 10 km2 was located in the best-preserved part of the Białowieża National Park (BNP), protected since 1921. Tree stands growing there have never been logged and have features of primeval forests, such as differentiated structure in terms of age and size of trees, the presence of uprooted fallen trees and large amount of dead wood [29]. Our study was conducted in an oak-lime-hornbeam stand (Tilio-Carpinetum), which is the dominant and most diversified forest type in the BNP. The main tree species in this stand are European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata Mill.), pedunculate oak (Quercus robur), Norway spruce (Picea abies), Norway maple (Acer platanoides L.), elms Ulmus spp., accompanied by many other species occurring as admixture, such as European ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) and common aspen.

2.2. Foraging Behaviour

Data were collected from 1999 to 2004 and from 2007 to 2011 during all months of the year. Observations of foraging woodpeckers were conducted during a random walk in the study area, which usually started one or two hours after sunrise and lasted until midday. Birds were detected by sounds or by systematic scanning of trees using binoculars. Once a woodpecker was located, its foraging time was measured, and the parameters of a foraging site were noted. Foraging time was measured from the moment when the foraging bird was located until it finished the foraging (the woodpecker most often flew to another tree or another place on the same tree). To avoid the over-representation of the records of the same individuals in the collected data, only the first observation of the woodpecker on a given place on the tree was recorded. Moreover, after a given observation, the observer moved a few hundred meters, and only then started searching for the next foraging woodpecker. The following parameters of foraging sites were recorded: (1) tree species, (2) tree condition (live or dead), (3) tree diameter at breast height (DBH), (4) part of a given tree (trunk or branch), (5) condition of a foraging site (live or dead), (6) diameter of a foraging site, and (7) height of a foraging site above the ground. DBH was calculated by measuring the trunk perimeter with a tape measure. The diameter of a foraging site was visually assessed, using the woodpecker body size as a reference. Suunto Height Meter PM-5/1520 or researcher height as a reference was used to assess foraging height. In cases where a woodpecker was moving along a tree trunk or a branch while foraging, and at the same time the diameter or height of the foraging site changed, the initial and final size of each of these parameters were noted. Diameter of each foraging site was assigned to one of the three classes: <15 cm, 15–30 cm, >30 cm. The height of a foraging site above the ground was assigned to one of the five classes: <5 m, 5–10 m, 10–15 m, 15–20 m, >20 m. This approach was followed because both the diameter of a foraging site and the height of foraging were determined to a certain degree, and they changed when a woodpecker was moving while foraging. In addition, the foraging technique of woodpeckers was recorded, which was divided into three categories: gleaning, bark pecking, and wood pecking. Gleaning was defined as picking up food from the substrate surface. In this category, we also included searching and probing (using a bill or tongue to retrieve food from within the foraging substrate), which were very often combined with gleaning. Bark pecking was defined as striking the bark with a bill or scaling (removing pieces of bark), whereas wood pecking was defined as striking the barkless part of a tree with a bill. The observations throughout the study period were performed by three persons, who individually penetrated the study area and recorded parameters of foraging sites. To ensure that the estimates of the recorded parameters (e.g., diameter, height) were the same, and thus data from different observers were comparable, these estimates were repeatedly compared and calibrated both during this study and other studies conducted for many years in the Białowieża Forest.

2.3. Habitat Measurements

To determine trees preferred by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker as foraging sites, we assessed tree resources in the primeval oak-lime-hornbeam stand based on 55 randomly selected plots (0.25 ha each) within the study area. Measurements were conducted from 1999 to 2003 and included all standing trees. For each tree, the species, condition (live or dead), and DBH of a trunk were recorded.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data from different years were pooled and then analyzed by period: the breeding season (April to June) and the non-breeding season (other months) [30,31]. A total of 449 records were collected, including 332 records in the breeding season (215 in April, 93 in May, 24 in June) and 117 records in the non-breeding season (15 in January, 23 in February, 20 in March, 6 in July, 3 in August, 3 in September, 30 in October, 9 in November, 8 in December). An observation of a foraging woodpecker on a given tree was considered as one record. To determine which trees are preferred by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker as foraging sites in terms of species, condition (dead/live), and dimensions (expressed as a trunk DBH), we calculated the selection indices following Manly et al. [32]. To analyse tree preferences according to their size, trees were divided based on the DBH into four classes: <20 cm, 20–40 cm, >40–60 cm, and >60 cm. Selection indices were calculated by dividing the proportion of trees visited during foraging (species, condition, size class) by the proportion of available trees from a particular group with a DBH of at least 2.5 cm (the minimum DBH of trees on which the Middle Spotted Woodpecker was observed foraging during the study period). A selection index significantly greater than 1 indicated preference, whereas an index smaller than 1 indicated negative selection. To assess whether a selection index was statistically significant, we constructed 95% simultaneous confidence limits for each index following Manly et al. [32]. Negative lower limits were changed to 0.00, because negative values of confidence limits are not possible. A selection index was considered statistically significant if its confidence limits did not contain the value of 1 [32]. We used a G-test to compare the parameters of foraging sites and foraging techniques between the breeding and non-breeding seasons. Prior to these analyses, the foraging time was converted into percentages, i.e., the percentage of foraging time on a given tree species, on trees in a given size category, on a given height category, etc. was calculated. To check which variables are associated with the duration of a foraging session of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker, a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a gamma error distribution and log-link function was built. As a “foraging session”, we considered foraging time of one bird in one site on a tree. The following parameters of foraging sites were included in the analyses as fixed categorical explanatory variables: tree species, foraged part of a tree, foraging height, diameter of a foraging site, and its condition. DBH was included as a continuous explanatory variable. The “tree condition” was excluded from the analysis, because this variable and the “condition of a foraging site” are closely related (i.e., a dead tree provides only dead foraging sites). In addition, we included “season” as a fixed categorical explanatory variable to assess whether there was a difference in the duration of a forging session between both seasons. The year of the study was included as a random variable. If the GLMM showed a significant effect of a fixed explanatory variable, paired contrasts were calculated to evaluate differences between levels of a given variable (if larger than two). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 for Windows, whereas the distribution of dependent variable was checked using Statistica 12.0 software.

3. Results

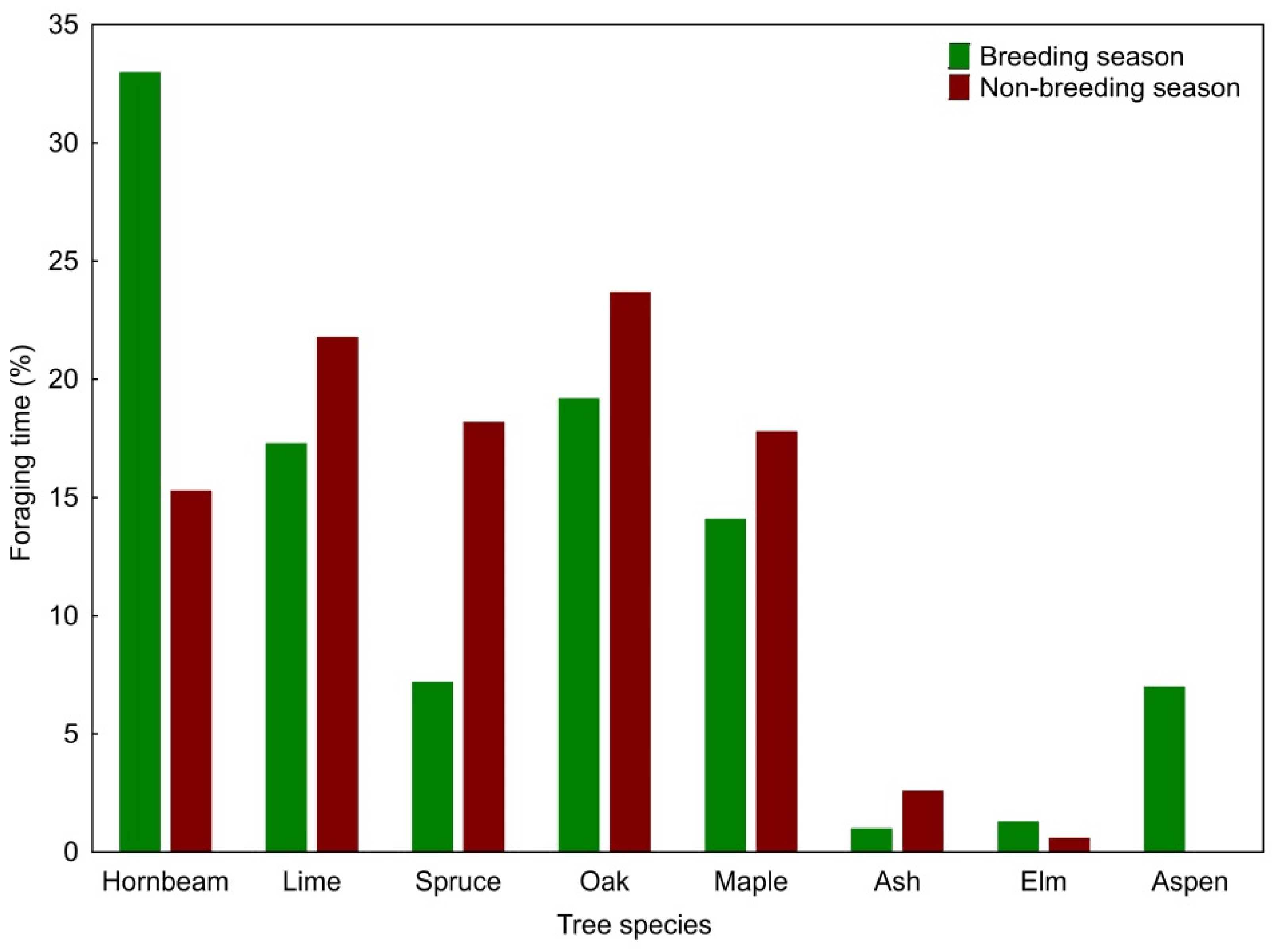

The Middle Spotted Woodpecker foraged on eight tree species during the breeding season and on seven tree species during the non-breeding season. The use of tree species (expressed as a percentage of foraging time) differed between the seasons (G = 23.63; df = 7; p = 0.001). In the breeding season, woodpeckers foraged most frequently on European hornbeams (33% of the observation time), but they also spent a significant percentage of the foraging time on pedunculate oaks, small-leaved limes, and Norway maples (Figure 1). The selection indices showed a significant preference for pedunculate oaks, Norway maples, common aspens and European hornbeams, while avoidance for small-leaved limes and Norway spruces (Table 1). In the non-breeding season, the Middle Spotted Woodpecker frequently foraged on pedunculate oaks, small-leaved limes, Norway spruces, Norway maples and European hornbeams, but pedunculate oak and Norway maple were the only tree species for which the selection indices showed a statistically significant preference (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Middle Spotted Woodpecker foraging time in relation to tree species in the breeding and non-breeding seasons.

Table 1.

Trees used by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker during foraging according to species, condition and size in relation to available resources. The “other category” includes: common hazel (Corylus avellane L.), rowan (Sorbus aucuparia L.), birch (Betula spp.). Nr, the number of trees in resources measured on 55 sample plots, (mean and standard error are presented in brackets); Nf, the number of visited trees during foraging. Selection indices are presented with 95% confidence limits (in brackets). Asterisks show statistically significant results.

In both seasons, the Middle Spotted Woodpecker foraged more time on live than dead trees (Table 2), but the comparison with available resources suggested that the latter were preferred (Table 1). There was no difference in the use of live and dead trees between the breeding and non-breeding seasons (test G = 0.10; df = 1; p = 0.751).

Table 2.

Percentage distribution of foraging time of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker in relation to tree condition, DBH, condition of the site used, part of a tree, diameter of the part used, foraging height and foraging technique. Asterisk shows the parameter that differs between the breeding and non-breeding seasons.

The most preferred trees in both seasons were the largest ones, with a DBH above 60 cm (Table 1). During the non-breeding season, the Middle Spotted Woodpecker spent more than half of its foraging time on trees belonging to this thickness class (Table 2). On the other hand, the smaller diameter trees (up to 20 cm DBH) were used by woodpeckers to a small extent in both seasons (Table 2) and the selection indices suggested that they were avoided, which was particularly evident in the non-breeding season (Table 1). The use of trees in specific DBH classes did not differ between the seasons; however, the result was close to significance (G = 7.34; df = 3; p = 0.062). The Middle Spotted Woodpecker spent more time on live parts of trees than on dead ones (Table 2) and the percentage distribution of time spent foraging on those parts of trees did not differ between the breeding and non-breeding seasons (test G = 0.26; df = 1; p = 0.609). Woodpeckers used more time on tree trunks than on limbs (Table 2) and the proportion of time spent foraging on these two sites did not differ between the seasons (G = 1.30; df = 1; p = 0.255). During the breeding season, foraging time slightly increased with increasing diameter of the substrate used, which was not observed in the non-breeding season (Table 2), but the difference between the seasons was not significant (test G = 4.11; df = 2; p = 0.128). The use of trees of different heights varied in both seasons (test G = 15.89; df = 4; p = 0.003). In the non-breeding season, woodpeckers foraged at higher levels compared with the breeding season, spending as much as 75% of their time at heights above 10 m (Table 2). In both seasons, prey gleaning from the tree surface was the dominant foraging technique, however, bark pecking also accounted for a significant percentage of foraging time (Table 2) The proportion of time spent on specific foraging techniques did not differ between the breeding and non-breeding seasons (test G = 0.90; df = 2; p = 0.638).

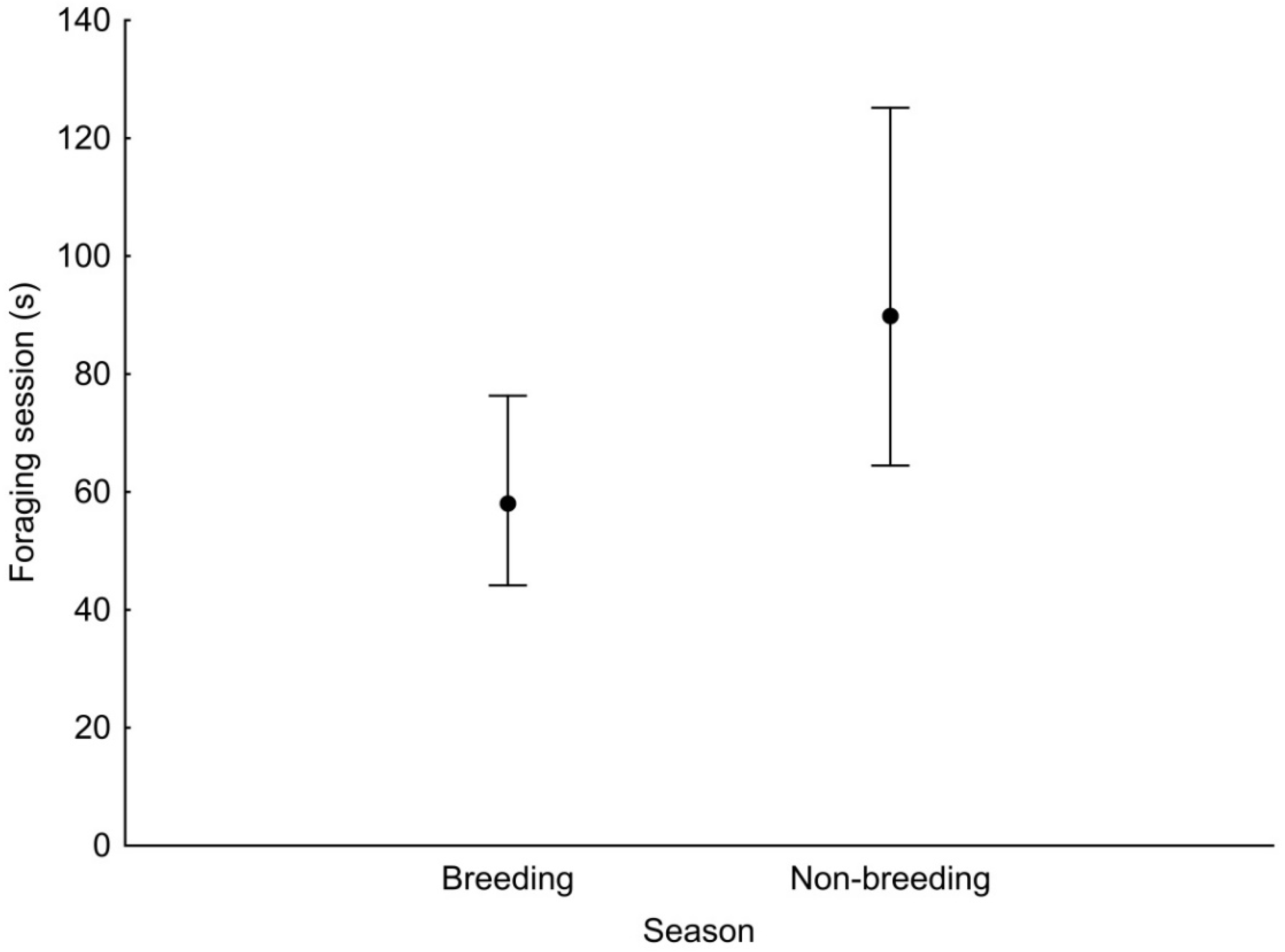

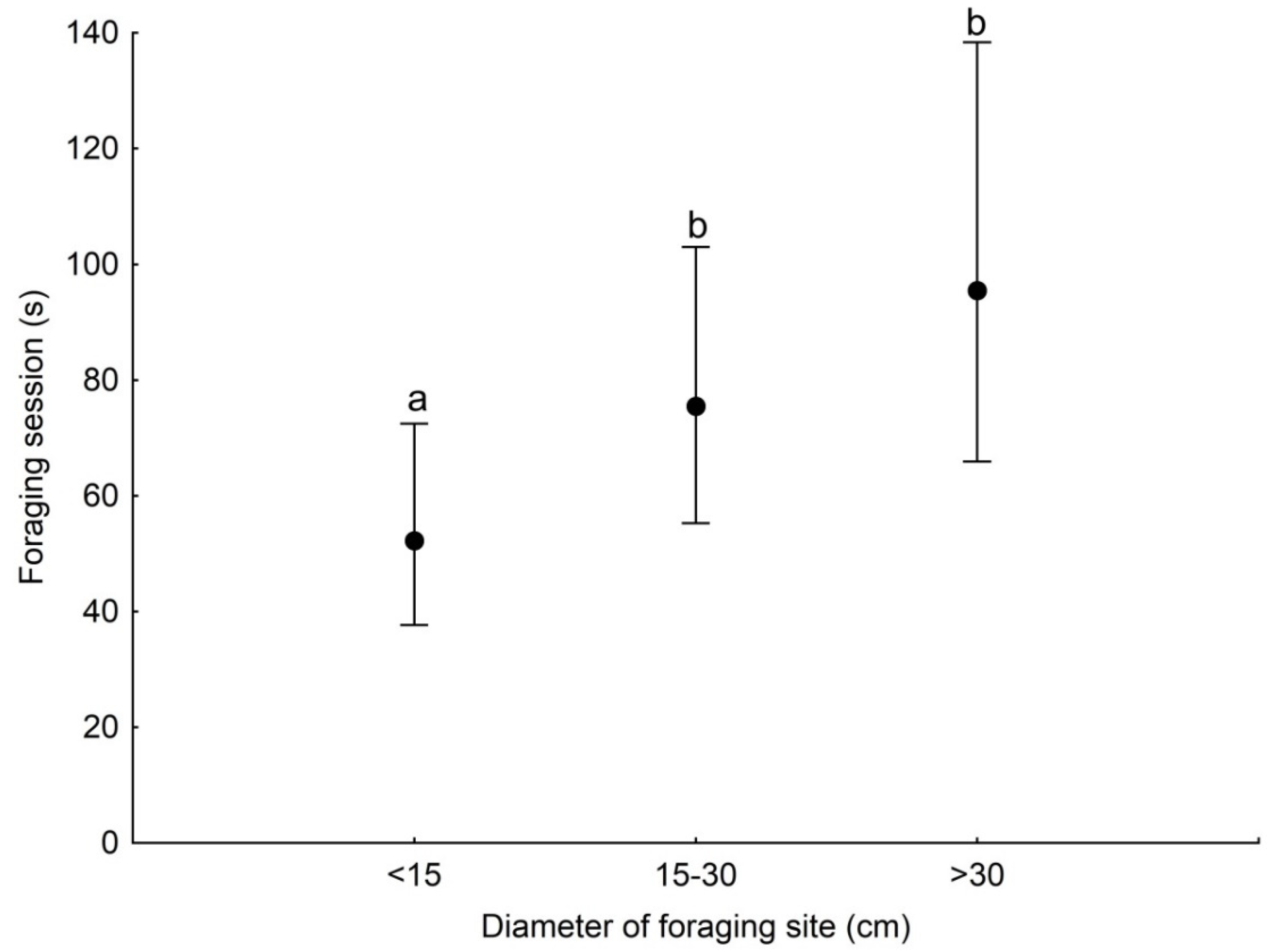

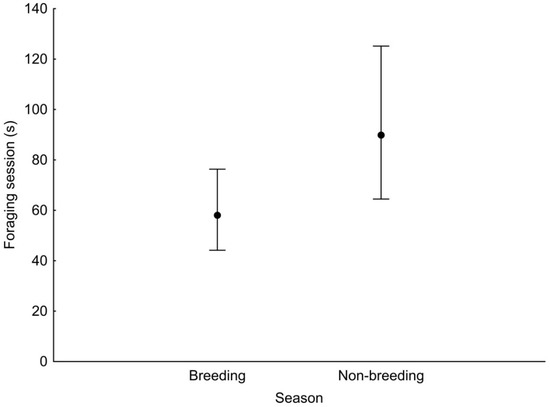

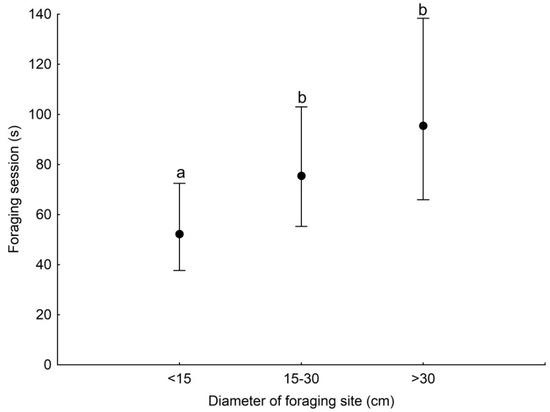

GLMM analysis showed that the duration of a foraging session was associated with the season and the diameter of the substrate used (Table 3). Foraging session was significantly longer during the non-breeding season than in the breeding season (Figure 2). Woodpeckers foraged significantly longer at sites with a diameter of 15–30 cm and >30 cm compared with sites with a diameter of <15 cm (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Results of GLMM analysis assessing the effect of variables on the duration of a foraging session of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker in primeval oak-lime-hornbeam forest in the BNP.

Figure 2.

Least squares means with 95% confidence limits (from the statistical model presented in Table 3) of the duration of a foraging session of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker in breeding season and non-breeding season.

Figure 3.

Least squares means with 95% confidence limits (from the statistical model presented in Table 3) of the duration of a foraging session of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker at sites with different diameters. Different letters indicate significant differences between different categories of foraging.

4. Discussion

Our study showed that, as expected, pedunculate oaks were preferred by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker during foraging both in the breeding and non-breeding seasons. This is consistent with findings of previous studies [8,9,10,12]. On the other hand, the study suggested that the duration of a foraging session was not affected by a tree species, but by the diameter of the tree substrate on which a woodpecker foraged. This phenomenon may suggest that the tree species is not as important as the surface area of a site from which the Middle Spotted Woodpecker collects food. Our findings were indirectly consistent with the findings reported in the available literature. For example, Zehetmair [33] found that the presence of this woodpecker is related not only to the occurrence of oaks, but mainly to the hardwood surface area provided by deciduous tree species with rough bark. Similarly, Wichmann and Frank [34] showed that the presence of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker was correlated with the number of rough-barked trees. The foraging preference for oaks shown in many studies is probably due to their large size and rough bark, whereas the avoidance of other tree species is due to their insufficient size and smooth bark. The fissured bark of oaks makes them an excellent habitat for invertebrates [26,27]. The same situation concerned Norway maples, which were also preferred in both analysed seasons. In the BNP, however, many tree species whose bark is usually smooth reach larger dimensions than in other areas. The bark of such trees is often full of cracks and crevices, providing many invertebrates with a good habitat. This was the case, for example, with European hornbeam. Our study revealed that this was the tree species preferred by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker as a foraging site, during the breeding season. During this season, woodpeckers visited European hornbeams most frequently and spent more time foraging on them compared with all other tree species, which suggests that European hornbeams in the BNP are the habitat for numerous invertebrates that are food for the Middle Spotted Woodpecker. Some authors report foraging of this woodpecker species on European hornbeam [9,11], but only Kruszyk [10] reported its significant use at 20%. Our study suggested strong preference for common aspen, although this tree was used solely in breeding season. Moreover, this tree species in oak-lime-hornbeam stand, occurring only as admixture.

Our second assumption that larger diameter trees are preferred by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker was also confirmed. This was particularly evident during the non-breeding season, when woodpeckers mostly foraged on trees with a DBH of more than 60 cm. On the other hand, woodpeckers foraged on smaller diameter trees (up to 20 cm DBH) extremely rarely, especially during the non-breeding season. Pasinelli and Hegelbach [9] obtained similar results to ours, showing that the Middle Spotted Woodpecker used trees with DBH < 36 cm at low levels, but showed a strong preference for oaks in the 36–72 cm DBH class. Our study showed that, in addition to the tree trunk diameter, the diameter of a foraging site on a tree was important for woodpeckers. Foraging sessions were shortest at sites with thinner diameters, which confirmed the key role of the surface area of a site from which the Middle Spotted Woodpecker collects food. Moreover, the percentage of total foraging time in the breeding season increased with increasing diameter of a foraging site. On the other hand, woodpeckers showed no preference for any particular diameter class in the non-breeding season, and the foraging time on the thinnest substrates was equal to the foraging time on the thickest substrates. This latter finding may suggest that, outside the breeding season, when resources are very often limited, thin branches are as good food storage as thick trunks or limbs. The attractiveness of such foraging sites for the Middle Spotted Woodpecker in winter was confirmed by some authors [10,11,35]. For example, the study by Kruszyk [10] showed that, from November to March, woodpeckers spent almost half of their time foraging on thin branches (up to 5 cm in diameter).

The foraging techniques used by the Middle Spotted Woodpecker in the BNP (searching, surface probing and gleaning) did not differ from those described in other areas [1,9,11,36]. The only difference was the frequency of bark pecking and scaling in the BNP. This took almost 1/3 of the total foraging time, while in other areas this method was not used at all or was used occasionally [7,9,10,35]. The study by Osiejuk [8] from western Poland was the only study that showed very frequent use of bark scaling (almost half of foraging time). During our study, we did not observe any ringing of trees or sap sucking by Middle Spotted Woodpeckers. This type of foraging is recorded for this woodpecker species usually in March and April, but not with great intensity [9,10,12,35]. Sipping sap from trees and eating invertebrates attracted by it supplements the diet of woodpeckers, which is important especially in periods of limited abundance of invertebrates, e.g., in early spring [37,38]. The absence of such foraging behaviour in the Middle Spotted Woodpecker in the BNP may suggest that during periods with limited food resources, there is still a sufficient amount of food for woodpeckers, for example, inside of dead spruces [39].

Our study showed that the foraging sites of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker in both seasons were similar in many respects; however, we found two differences regarding tree species and foraging height. The first difference is mainly due to the fact that the use of hornbeams in the non-breeding season decreased by a factor of two, whereas the use of Norway spruces increased more than twice compared with the breeding season. This suggests that Norway spruces are a good store of woodpeckers’ food, in the form of insects, which can overwinter inside the wood [25,40]. The important role of this tree species as a good foraging site in the BNP was confirmed for the White-backed Woodpecker [17] and the Great Spotted Woodpecker [39]. However, other authors observed no or sporadic foraging of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker on spruces [9,10,11,12]. We found that foraging sites of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker were located higher on the trees during the non-breeding season compared with the breeding season. There may be several explanations for this phenomenon. Firstly, during the non-breeding season, woodpeckers spend more time foraging on Norway spruces, which are the tallest trees in the BNP, reaching over 50 m in height; whereas, during the breeding season, they spend more time on hornbeams, which are one of the lowest tree species in the Białowieża Forest [41]. Secondly, in order to collect a sufficient amount of food, the Middle Spotted Woodpecker probably has to search a larger area in the non-breeding season than during the breeding season. Thus, woodpeckers moving upwards cover a greater distance and reach much higher. Thirdly, sites located higher up in trees have better sun exposure compared with those located at lower levels. Pasinelli and Hegelbach [9] showed that the most attractive foraging sites for the Middle Spotted Woodpecker should be exposed to sunlight, as more insolated trees or their sections have a richer invertebrate fauna [27]. Thus, it seems that, in periods with limited resources, woodpeckers more often forage at higher located sites. Similar results to ours were reported by Pettersson [12], showing that woodpeckers foraged from November to March in higher tree strata compared with May and April. However, the opposite results were obtained by Jenni [11]. He showed that the Middle Spotted Woodpecker spent more time from April to June foraging in the upper canopy layer; whereas, from November to March, it spent more time in the lower canopy layer.

We found that woodpeckers spent more time foraging in one site (tree) in the non-breeding season compared with the breeding season. It suggests that the more efficient feeding strategy during colder periods of the year is longer, i.e., detailed exploitation of food in one site or tree than more frequent changing sites and flying between trees. A similar result in the case of White-backed Woodpecker was obtained by Czeszczewik [17], who revealed that the duration of the foraging session was the shortest in the breeding season, longer in the post-breeding season and the longest in winter. The urgency to feed the nestlings is also a likely explanation for why foraging session time was shorter during the breeding season. Finding food for the young as quickly as possible is likely to require woodpeckers to find food closer to the nest to minimise travel time back to the nest and to minimise the rate at which the young are fed. As a consequence of this necessity, food in the habitat close to the nest would be neglected before the nesting season in favour of food found at greater distances from the nest. Moreover, food resources for nestlings (e.g., Lepidoptera larvae) play a significant role, usually abundant at that time, and can therefore be collected within a short period of time.

Our results may be influenced by differences in foraging behavior between the sexes of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker. Pasinelli [35] found in his study that males and females differed in the use of tree species, foraging techniques, height zones and live and dead substrates within a tree. Females spent more time in the lower canopy than males during the breeding period, which means females may be easier to detect during this time. Moreover, differences between the sexes in foraging site selection were less pronounced during the breeding season compared with the pre-breeding season.

5. Conclusions

Our results suggest that the preferred foraging site of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker should be sufficiently thick during the breeding season while, during the non-breeding season, it should be located higher up in a tree. Both of these requirements are met by pedunculate oaks and hence probably the strong preference of woodpeckers for these trees in the two periods compared. In the non-breeding season, woodpeckers foraged at sites located higher, and the foraging session was longer compared with the breeding season. In both seasons, woodpeckers preferred dead and large trees and prey gleaning from the tree surface was their dominant foraging technique. Our results confirmed the key role of oaks and large trees, but also revealed the importance of European hornbeams and Norway spruces as foraging sites for the Middle Spotted Woodpecker.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S., M.S., A.G. and D.C.; methodology, T.S. and D.C.; validation, T.S. and A.G.; formal analysis, T.S.; investigation, T.S. and D.C.; resources, T.S. and D.C.; data curation, T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, T.S., M.S., A.G. and D.C.; visualization, T.S.; supervision, T.S. and D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities. The APC was funded by Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the authorities of the Białowieża National Park for their help during our research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pasinelli, G. Dendrocopos medius Middle Spotted Woodpecker. BWP Update 2003, 5, 49–99. [Google Scholar]

- Spühler, L.; Krüsi, B.O.; Pasinelli, G. Do Oaks Quercus spp., dead wood and fruiting Common Ivy Hedera helix affect habitat selection of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos medius? Bird Study 2014, 62, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiński, Z.; Pluta, M.; Ulanowska, A.; Walczak, Ł.; Winiecki, A.; Zarębski, M. Do increases in the availability of standing dead trees affect the abundance, nest-site use, and niche partitioning of great spotted and middle spotted woodpeckers in riverine forests? Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 27, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pettersson, B. Extinction of an isolated population of the middle spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos medius (L.) in Sweden and its relation to general theories on extinction. Biol. Conserv. 1985, 32, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikusiński, G.; Angelstam, P. European woodpeckers and anthropogenic habitat change: A review. Vogelwelt 1997, 118, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Bühlmann, J.; Müller, W.; Pasinelli, G.; Weggler, M. Entwicklung von Bestand und Verbreitung des Mittelspechts Dendrocopos medius 1978-2002 im Kanton Zürich: Analyse der Veränderungen und Folgerungen für den Artenschutz. Ornithol. Beob. 2003, 100, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Török, J. Resource partitioning among three woodpecker species Dendrocopos spp. during the breeding season. Holarct. Ecol. 1990, 13, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiejuk, T.S. Locomotion patterns in wintering bark-foraging birds. Ornis Fenn. 1996, 73, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Pasinelli, G.; Hegelbach, J. Characteristics of trees preferred by foraging Middle Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos medius in northern Switzerland. Ardea 1997, 85, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kruszyk, R. Population density and foraging habits of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos medius and Great Spotted Woodpecker D. major in the Odra valley woods near Wrocław. Notatki Ornitol. 2003, 44, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jenni, L. Habitatsnutzung, Nahrungserwerb und Nahrung von Mittel- und Buntspecht (Dendrocopos medius und D. major) sowie Bemerkungen zur Verbreitungsgeschichte des Mittelspechts. Ornithol. Beob. 1983, 80, 29–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, B. Foraging behaviour of the Middle Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos medius in Sweden. Holarct. Ecol. 1983, 6, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walankiewicz, W.; Czeszczewik, D.; Mitrus, C.; Bida, E. Snag importance for woodpeckers in deciduous stands of the Białowieża Forest. Notatki Ornitol. 2002, 43, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Walankiewicz, W.; Czeszczewik, D. Use of the Aspen Populus tremula by birds in primeval stands of the Białowieża National Park. Notatki Ornitol. 2005, 46, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wesołowski, T.; Czeszczewik, D.; Hebda, G.; Maziarz, M.; Mitrus, C.; Rowiński, P. 40 years of breeding bird community dynamics in a primeval temperate forest (Białowieża National Park, Poland). Acta Ornithol. 2015, 50, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolstad, J.; Rolstad, E. Influence of large snow depths on Black Woodpecker Dryocopus martius foraging behavior. Ornis Fenn. 2000, 77, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Czeszczewik, D. Foraging behaviour of White-backed Woodpeckers Dendrocopos leucotos in a primeval forest (Białowieża National Park, NE Poland): Dependence on habitat resources and season. Acta Ornithol. 2009, 44, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, K.L.; Gow, E.A. Choice of foraging habitat by northern flickers reflects changes in availability of their ant prey linked to ambient temperature. Ecoscience 2013, 20, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, W. Age-dependent choice of redshank (Tringa totanus) feeding location: Profitability or risk? J. Anim. Ecol. 1994, 63, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heithaus, M.R. Habitat use and group size of pied cormorants (Phalacrocorax varius) in a seagrass ecosystem: Possible effects of food abundance and predation risk. Mar. Biol. 2005, 147, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańska, M.; Stański, T.; Hawryluk, J. Spider assemblages on tree trunks in primeval deciduous forests of the Białowieża National Park in eastern Poland. Entomol. Fenn. 2018, 29, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańska, M.; Stański, T. Plant-dwelling spider communities of three developmental phases in primeval oak-lime-hornbeam forest in the Białowieża National Park, Poland. Eur. Zool. J. 2021, 88, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwood, T.R.E.; Wint, G.R.W.; Kennedy, C.E.J.; Greenwood, S.R. Seasonality, abundance, species richness and specificity of the phytophagous guild of insects on oak (Quercus) canopies. Eur. J. Entomol. 2004, 101, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukovata, L.; Jaworski, T. The abundance of the nun moth and lappet moth larvae on trees of different trunk thickness in Scots pine stands in the Noteć forest complex. Leśne Prace Badaw. 2010, 71, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lõhmus, A.; Kinks, R.; Soon, M. The importance of deadwood supply for woodpeckers in Estonia. Balt. For. 2010, 16, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Southwood, T.R.E. The number of species of insects associated with various trees. J. Anim Ecol. 1961, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, V. The bark of trees: Thermal properties, microclimate and fauna. Oecologia 1986, 69, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlík, Š. Woodpeckers as predators of leaf-eating lepidopterus larvae in oak forests. Tichodroma 1997, 10, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Tomiałojć, L. Characteristics of Old Growth in the Białowieża Forest, Poland. Nat. Areas J. 1991, 11, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski, Z.; Ksit, P. Comparative reproductive biology of Middle Spotted Woodpeckers Dendrocopos medius and Great Spotted Woodpeckers D. major in a riverine forest. Bird Study 2006, 53, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesołowski, T.; Hebda, G.; Rowiński, P. Variation in timing of breeding of five woodpeckers in a primeval forest over 45 years: Role of food, weather, and climate. J. Ornithol. 2021, 162, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manly, B.F.J.; McDonald, L.L.; Thomas, D.L.; McDonald, T.L.; Erickson, W.P. Resource Selection by Animals. In Statistical Design and Analysis for Field Studies, 2nd ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 46–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehetmair, T. Vergleichende Untersuchung von Revieren des Mittelspechts Dendrocopos medius im “Nördlichen Feilenforst”. Ornithol. Anz. 2009, 48, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann, G.; Frank, G. Die situation des Mittelspechts (Dendrocopos medius) in Wien. Egretta 2005, 48, 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pasinelli, G. Sexual dimorphism and foraging niche partitioning in the Middle Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos medius. Ibis 2000, 142, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanicsek, L. The study of bird species foraging on the bark. Aquila 1988, 95, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Turček, F. The ringing of trees by some European woodpeckers. Ornis Fenn. 1954, 31, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kruszyk, R. Sap-sucking in the European woodpeckers Picidae. Notatki Ornitol. 2005, 46, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stański, T.; Czeszczewik, D.; Stańska, M.; Walankiewicz, W. Foraging behaviour of the Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major in relation to sex in primeval stands of the Białowieża National Park. Acta Ornithol. 2020, 55, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilszczański, J. Bark of dead infested spruce trees as an overwintering site of insect predators associated with bark and wood boring beetles. Leśne Prace Badaw. 2008, 69, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlaczyk, P. Forest communities. In Białowieża National Park, Know It—Understand It—Protect It; Okołów, C., Karaś, M., Bołbot, A., Eds.; Białowieski Park Narodowy: Białowieża, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).