Abstract

The dieback of common ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) has dramatically decreased the abundance of the species in Europe; however, tolerance of trees varies regionally. The tolerance of trees is considered to be a result of synergy of genetic and environmental factors, suggesting an uneven future potential of populations. This also implies that wide extrapolations would be biased and local information is needed. Survival of ash during 2005–2020, as well as stand- and tree-level variables affecting them was assessed based on four surveys of 15 permanent sampling plots from an eastern Baltic region (Latvia) using an additive model. Although at the beginning of dieback a relatively low mortality rate was observed, it increased during the 2015–2020 period, which was caused by dying of the most tolerant trees, though single trees have survived. In the studied stands, ash has been gradually replaced by other local tree species, though some recruitment of ash was locally observed, implying formation of mixed broadleaved stands with slight ash admixture. The survival of trees was related to tree height and position within a stand (relative height and local density), though the relationships were nonlinear, indicating presence of critical conditions. Regarding temporal changes, survival rapidly dropped during the first 16 years, stabilizing at a relatively low level. Although low recruitment of ash still implies plummeting economic importance of the species, the observed responses of survival, as well as the recruitment, imply potential to locally improve the survival of ash via management (tending), hopefully providing time for natural resistance to develop.

1. Introduction

The dieback of common ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.), which has been occurring in Europe since the end of the 20th century and threatens the existence of the species [1,2], reveals the ecological and economical effects of major biotic changes in forests [2,3,4,5]. Despite high infection pressure, common ash is still struggling to survive, with 1–10% of trees considered to be resistant [6,7,8,9,10]. Nevertheless, considering the importance of common ash in Europe, efforts are still continuing to maintain the species despite the persisting pathogen pressure [3,11,12,13,14]. As the pathogen is rapidly decreasing the abundance of its host, natural selection of less virulent strains of the fungus is expected to emerge, hopefully leading to a dynamic equilibrium, which needs time to occur [7,15]. Also, the heritable genetic variation of resistance suggests potential for common ash to recover via natural selection in the long run [10,13,16]. Still, due to the devastating dieback, breeding programs and seedling propagation have been postponed [17,18], highlighting knowledge-intensive adaptive management of naturally regenerating ash as the main path to sustain the species in Europe [12,16,19].

The economic merits of common ash are plummeting, but still it is highly ecologically important [2,3,5,20], hence the majority of the recent studies have addressed the potential for improvement of its resistance to the dieback [7,13,14]. Previous studies agree that, although high, the susceptibility of common ash to dieback is affected by intrinsic and environmental (stand, landscape, weather, etc.) factors [3,11,12,21,22,23], implying complex ecological interactions [8,21,24]. In most of the studies, the variables affecting the susceptibility of ash appear similar; however, their effects and interactions can differ regionally or even locally [8,18,22,25,26]. Regionally specific biotic interactions and resistance to dieback implies an uneven potential for common ash in the future [3,27]. Nevertheless, these effects also imply potential to facilitate persistence or even some sustainability of common ash via region specific management [8,23,25,28].

The effects of stand composition and structure on the susceptibility of common ash to dieback have been related to microclimate [22,23,29], as well as the biological and physical barriers affecting the spread and development of the infection [30,31,32,33]. Common ash in mixed stands has been reported to be less damaged, when compared to pure stands [5,11,34]. Although the climate throughout the range of common ash is suitable for the causal agent of the dieback Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (Kowalski) [1,2], temperature and, particularly, moisture regime can modulate infection pressure, and hence susceptibility of ash [12,23,27,35]. The younger and smaller trees, particularly in the understory, have been shown to be more susceptible to H. fraxineus due to its occurrence in more humid conditions, as well as stress caused by competition [29,36]. The larger (taller) trees are often less affected [21,29], which has been related to a better vigor and higher amount of non-structural carbohydrates [21], as well as lower quantity of the disease propagules at the upper canopy [37,38,39]. Though, the largest trees might also be biologically aged, thus relaxing their vigor and resistance [21]. Also, better health conditions have been reported for ash growing in the less dense stands, where microclimate is drier, while isolated solitary trees are even less affected [26,35]. Accordingly, management by reducing competition and improving light conditions is among the most effective means to facilitate the survival of common ash [11,34,35].

Several haplotypes of common ash have been distinguished in Europe, with the most abundant one (H01) occupying a vast area in the northern part of the species range including the Eastern Baltic region [40], suggesting its ecological plasticity [41,42]. Higher genetic diversity has been observed for “newer” and expanding populations [43]. Concerning the northern haplotype, the resistance of ash to the pathogen appears genetically controlled [10], implying potential for breeding [16,28], if such is revisited, though strong resistance has not been documented [10,13,29]. Also, the genetic diversity of ash near its northern range implies explicit local adaptation [42,43,44], suggesting local differences in susceptibility. In the Eastern Baltic region (Latvia), the mortality of ash during the recent decades has been lower if compared to many European countries [45], which might also be related to climatic and micro-climatic conditions, as well as forest landscapes and connectivity of the stands [22,29,46].

The non-native origin (Eastern Asia) of the causal agent—H. fraxineus—[47,48] implies that the general reason behind ash dieback is the assisted migration of the pathogen. Analogically, the risk of large-scale invasions persists also for other species [49,50], highlighting the necessity for maximizing the adaptive capacity of tree populations and forests as a whole [51]. Under such conditions, comprehensive information about the factors and mechanisms influencing short- and particularly long-term survival of trees is essential for implication of efficient adaptive management in the future [52]. The aim of the study was to assess the long-term survival of ash in the eastern Baltic region in Latvia and the main tree- and stand-level variables affecting it. We hypothesized survival to be affected by stand composition and tree size. We also assumed that the effect of these variables might be non-linear.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Measurements

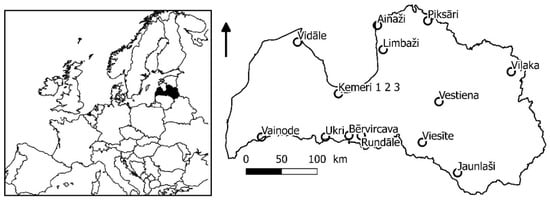

The long-term changes in common ash stands in Latvia were assessed based on the survey from 15 permanent sampling plots scattered across the country (Figure 1). The plots were established in 2005 in uneven-aged (51 to 138 years in 2005) stands initially dominated or co-dominated by common ash (Table 1) and subjected to a different degree of dieback [53]. At the beginning of the survey in 2005, the total density of alive trees in studied stands varied from 170 to 1203 trees ha−1 (mean 617 trees ha−1). Common ash was the dominant or codominant species with the mean density (± standard deviation) of 256 ± 55 trees ha−1. In two stands the proportion of ash exceeded 80%, while the others were mixed. The topography of the plots was generally flat, with the absolute elevation ranging 8–210 m a.s.l. Soil in most of the plots was mesotrophic dry mineral (silty), yet Ķemeri and Ainaži plots were located on mesotrophic periodically waterlogged (gleyic) soils.

Figure 1.

Location of the studied permanent sampling plots.

Table 1.

Details of the studied permanent sampling plots at the beginning of survey in 2005.

Climatic conditions in at the permanent plots can be classified as moist continental, though the locations of the sites represent local climatic gradient from coastal (west) to inland (east). Accordingly, the mean annual temperature (during 1980–2020) was 6.7 ± 0.9 and 6.4 ± 0.8 °C at the coastal and inland sites, respectively [54]. February and July were the coldest and the warmest months with mean monthly temperature ranging −2.9 ± 3.3–−4.3 ± 3.8 °C and 17.1 ± 1.6–17.7 ± 1.7 °C. The annual sum of precipitation in the western and eastern part of Latvia was 700 ± 90 and 687 ± 84 mm, respectively. The seasonal distribution of precipitation is uneven, with the highest monthly precipitation falling during the summer months (May–August, 74 ± 42 mm). An increase of temperature during the autumn–spring period coupled with growing heterogeneity of summer precipitation regime have been the main manifestations of climatic changes [55].

The permanent sampling plots were circular, with a radius of 15 m (area of ca. 706 m2). In each plot, all trees, including deadwood (log/snag), with stem diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 6 cm were accounted and numbered, and their coordinates fixed. For each tree (including deadwood and the recruiting ones), species, DBH and height (or length for lying deadwood) (H) were recorded with the accuracy of 1 cm and 50 cm, respectively. Such surveys were repeated four times: in 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020. In 2005, the age of ashes was determined from increment cores.

2.2. Data Analysis

For a general description of mortality of common ash across the studied stands between the surveys, as well as during the whole period, mortality rate r%:

where N1 was the number (or standing volume) of ashes at the beginning of the observation period, Nt was the number (or standing volume) of ash at the end of the observation period, t was the length of the observation period, in years. Only the ashes alive at the beginning of the survey were considered.

The effects of stand- and tree-level variables on survival of ash (binary variable), accounting for hierarchical data structure arising from the repeated measurements and non-linearity of the responses, were assessed using mixed generalized additive model assuming binomial distribution of the residuals [56]. Such models are sufficient for the analysis of heterogenic ecological data [57]. The tested tree-level variables (fixed effects) were DBH, H, approximation of stemwood volume (DBH2H), their relative values (relative to the mean value of stand at each survey), age, and competition index. Competition index (CI) was calculated for description of local density based on DBH of living trees within 5 m distance from a particular ash:

where DBHn(i) is the diameter at breast height for all surrounding trees and ln(i) is the distance from the i-th to all surrounding trees. The tested stand (sample plot) level variables (fixed effects) were number of tree species, stand density, density of common ash, proportion of ash from the standing volume, mean DBH, mean DBH of ash, mean H, mean H of ash, mean stem volume, mean stem volume of ash, and share (according to standing volume) of ash, black alder (Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn.), grey alder (Alnus incana (L.) Moench), spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.), and maple (Acer platanoides L.). The duration of the dieback (in years), which was considered to be occurring since 1997 [13], was tested as the time term. Survey was used as the first order autocorrelation (‘ar1′) term.

Arbitrary selection of the best performing sets of fixed effects was performed based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Trees nested within the site were used as the random effects. The restricted likelihood approach [56] was used to fit the models. Regression spline with shrinkage was used to smoothen the results. A generalized cross-validation procedure was used for estimation of the smoothing parameters avoiding overfit. Also, to avoid overfit, the basis dimension of the smoothing terms was restricted to four, implying response curves with a maximum of three inflection points. Model residuals were checked for normality and homogeneity (by diagnostic plots). The predictors were checked for collinearity using the variance inflation factor (variables with the criterion > 5 were discarded from the model. Data analysis was conducted in program R v. 4.0.3. [58], using libraries ‘car’ [59] and ‘mgcv’ [56].

3. Results

Over the 15 years of the survey, only 33 (12.1%) of the initially (in 2005) accounted 271 ashes of different dimensions had survived, resulting in the overall mortality rate of 5.9% year−1. The mortality rate, though, has not been stable between the surveys, revealing the down-spiraling struggle of ash. During the first two survey periods, the mortality rate was relatively low (<10% year−1; cf. [45]), yet it increased to 12% year−1 during 2016–2020 despite the low density of ash. The relative decrease of standing volume during the period 2016–2020 was even faster (13% year−1 compared to <8% year−1 during prior periods; 5.6% year−1 over the entire period). Nevertheless, during the survey, 49 new visually healthy ashes with DBH ≥ 6 cm were accounted (six in 2005–2015 and 43 in 2016–2020), of which one died. Though, 37 of the new ashes have regenerated in a single site (Jaunlaši). Accordingly, the mean density (±standard deviation) of ash in the sample plots plummeted from 256 ± 55 to 80 ± 77 trees ha−1 in 2005 and 2020, respectively (Supplementary Materials, Table S1), and the decrease in standing volume was even stronger (from 322 ± 89 to 52 ± 30 m3 ha−1, respectively).

The dieback of ash resulted in substantial changes in composition of the stands initially dominated by ash (>75% of standing volume), where stands were completely overgrown by shrubs (Padus avium Mill. and Corylus avellana L.) preventing establishment of other tree species. The stands co-dominated by ash or where ash was an admixture species were able to cope with dieback of ash in terms of stand density, as in 2020 the mean stand density was 609 ± 287 trees ha−1, which is comparable to that in 2005 (617 ± 311 trees ha−1). Still, in 2020, canopies had not yet closed as trees were small. Changes of composition in these stands, besides the dieback of ash, were moderate, as a gradual recruitment of other species was occurring since 2010 (Supplementary Materials, Table S1). Generally, the openings were regenerating with species, which were forming canopies of the stands. Two pioneer species, Norway maple Acer platanoides L. and common aspen Populus tremula L., as well as black alder Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn. have been recruiting canopy most abundantly, increasing their density from 64 ± 48 to 182 ± 153, from 35 ± 28 to 127 ± 109, and from 151 ± 100 to 235 ± 165 trees ha−1 in 2005 and 2020, respectively. During the surveys, wych elm Ulmus glabra Huds. has also been regenerating abundantly, yet since 2015 it has been dying off, with 288 ± 224 dead trees ha−1 occurring in 2020, thus limiting its recruitment (density increased from 160 ± 87 to 190 ± 168 trees ha−1 in 2005 and 2020, respectively). The density of the late-successional small-leaved lime Tilia cordata Mill. and Norway spruce Picea abies (L.) H. Karst. have been recruiting gradually, increasing their densities from 94 ± 87 to 120 ± 104 and from 148 ± 105 to 159 ± 111 trees ha−1.

The long-term survival of ash was affected by stand and, particularly, tree-level variable. The refined model was strictly significant (p-value < 0.001) and included 5 of the 23 variables tested (Table 2), showing intermediate R2, given that field data was analyzed. The effective degrees of freedom ranged from 1.9–2.8, indicating that the responses to the fixed effects were non-linear. Nevertheless, the effective degrees of freedom were below the restriction set for the basis dimension, indicating lack of overfit. The strength of the fixed effects on survival of ash across the stands differed, as indicated by the F-values, which ranged from 5.4 to 22.4 for competition index and tree height, respectively. Among the random effects, site had ca. two times higher variance than tree, highlighting the between-stand differences in survival.

Table 2.

Effective degree of freedom, their F-values and significance (p-values), as well as the variance of random effects.

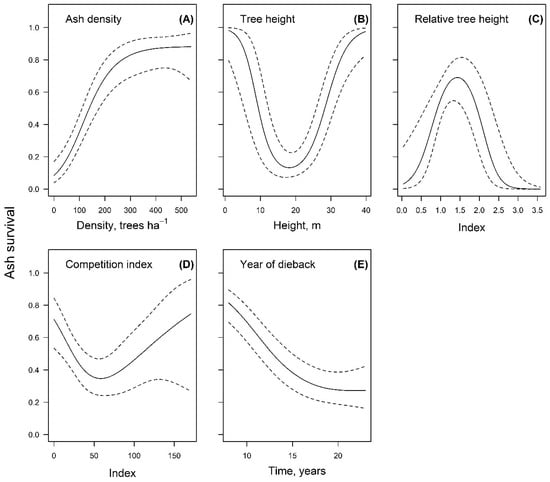

The prevailing size-dependence of survival was shown by the strength of the effect (highest F-value) of tree height as well as relative tree height (Table 2), while the responses were non-linear (Figure 2B,C). The response to height showed explicit local minimum for ca. 14–22 m tall trees, with the smallest and largest trees showing higher survival. Nevertheless, the effect of tree height was modulated by the social status of trees with the stands as shown by the response to relative tree height. Its effect, however, was opposite to tree height with the local maximum occurring for trees slightly above the mean of the stand (plot), as indicated by the index values ranging 1.1–1.8. The effect of the competition index, which reflects local stand density, was similar to tree height, as the local minimum was observed (Figure 2D). The response curve indicated that trees growing under low competition were more likely to survive, yet intermediate local density resulted in increased mortality. However, a further increase of local density tended to improve the survival, yet with higher uncertainty, likely due to effects of other unidentified variables. The mortality of ash was also density dependent as shown by the significant effect of ash density, though the relationships were generally positive (Figure 2A). The responses to density of ash and time since the onset of dieback (Figure 2A,E) showed threshold values, indicating intervals of rapid responses as well as the latent intervals. Regarding ash density, survival was high for stands while there were >ca. 250 ashes ha−1, yet a rapid drop occurred at lower values. The survival of trees was rapidly decreasing during the first ca. 16 years of dieback, after which, it stabilized, though at a low level (ca. 0.30).

Figure 2.

Nonlinear response of survival of common ash during 2005–2020 to tree- and stand level- level variables. The dashed lines indicate 95% confidence interval of the response curves ((A)—density of ash, (B)—height of ash, (C)—ash height relative to the mean of the stand, (D)—competition index representing local density, and (E) time since the supposed onset of the dieback).

4. Discussion

Metapopulations of trees with a wide range and/or growing near distribution limits show explicit local specialization, suggesting uneven potential for adaptation [41,43,44]. The long-term changes in abundance of ash (dynamics) and variables affecting survival of trees (Figure 2) showed local specifics, likely as a result of local specialization [42]. Previous studies have shown that ash has suffered lower mortality in Latvia if compared to the neighboring countries [45], likely due to the presence of “veteran” ash trees, which show an increased resistance [60]. These trees, which represent the generation that encountered a novel pathogen [7,14,15], were able to survive ca. five years longer, explaining the increase in mortality during the 2016–2020 period. Nevertheless, some of the most resistant trees still survive, implying presence of resistant genotypes [6,9,29]. Furthermore, an increased potential for development of resistance to the pathogen was suggested by the locally occurring recruitment of new ashes. Though the particular site (Jaunlaši) contained only slight admixture of ash, and occurred on the edge of a forest massif (Table 1). This might also be related to locally occurring natural selection of less virulent forms of the pathogen [7,13], particularly if abundance (population density) of the host has been low. As the regeneration of ash in Latvia is abundant [61], the occasional recruitment of trees in the larger diameter classes indicated the substantial contribution of the pathogen to sapling mortality [8,23,62]. Nevertheless, the rapid adaptation of trees to novel conditions over a few generations has been observed for trees growing near their distribution limit [7,63].

The changes in stand composition (Supplementary Materials, Table S1) and ecological consequences initiated by the dieback of ash, though inevitable, are region specific [19,27,64,65]. In the studied permanent sampling plots, the changes in stand composition due to ash dieback appeared depending on previous density of ash, suggesting varying transformation of stands [4,27] and varying potential for regeneration of ash [3,27,28]. In most stands, ash is being replaced by both early and late successional species [19,27,65], according to the composition of the remaining stand and intensity of disturbance, i.e., more pioneer species regenerate in stands initially co-dominated by ash. In the stands previously dominated by ash, a formation of shrubland occurred, postponing regeneration of stands and drawing succession back to earlier stages [64,65,66]. Among the recruiting tree species, elm has been replacing declining ash most abundantly, however, it also suffers dieback due to Dutch elm disease [67], thus subjecting stands to further transformations [4,68]. Considering the seed dispersal and high shade tolerance [69], Norway maple apparently is replacing ash, and likely also the elm. Major disturbances, such as ash dieback, can facilitate invasion of non-native species [70], leading to growing ecological consequences [68]. Invasive species were not observed, supporting gradual transformation of ash stands [64]. Still, the observed changes in composition of the studied stands and long-term mortality rate also suggest that ash would likely persist as a scarce admixture species with low density [66].

The hypothesis of the study was confirmed, as survival of ash was affected by tree- and stand-level variables, which had nonlinear effects (Figure 2), highlighting the complexity of the host–pathogen interactions [8,21]. Among the dimensions of trees, height, which is an indicator of productivity [71], appeared as the best predictor of survival among the studied dimension of trees (Table 2), suggesting an effect of site fertility. Furthermore, height had the strongest effect (highest F-value) among the identified variables. The response was quadratic, implying fluctuation in susceptibility as trees grow (Figure 2B) and a critical size to survive. The negative effect of height on survival for trees < 20 m in height, which most often were in the understory or suppressed, can be explained by competition [29,36] as well as ageing, when light requirements of trees shift [72]. Likewise, if trees were larger, reaching a higher canopy, they received more light, which improved their vigor and hence survival [21,27,29]. The effects of tree height might also be related to competition for light, microclimate, and vertical gradient of infection pressure [37,39]. Such complex relationships contribute to regional and local specifics of dieback [27,29].

The relationships between survival and the relative height of ash (Figure 2C) emphasized the effect of stand structure, hence microclimate and vertical gradient of infection pressure [26,35,37,38,39]. The reduced survival of the smaller trees can be explained by competition for light, which decreases non-structural carbohydrate reserves and hence resistance [21,29]. The decreased survival of the largest trees in stand might be related to wind damage, particularly when the collective stability is shattered by the loss of neighboring trees [73]. Even if trees are not windthrown, primary damage of wood and roots decreases tree vigor and resistance to pathogens [73,74], e.g., favoring development of Armillaria spp. [75]. Also, the largest trees suffer higher evapotranspiration, more often causing water deficit, which can weaken trees [76]. The response to competition index (Figure 2D), showed non-stationary effect of stand density. At low densities (CI < 50), an increase in competition decreased the survival, likely weakening trees. However, at a higher local density, the opposite reaction might be explained by the survival strategy of suppressed trees, when the resources are mobilized for defense and resilience, rather than growth, thus facilitating survival [77].

Dependence of survival on population density is primarily related to transmission of the infection, which is facilitated in cases of high population density [16,23,26]. The generally positive response to increasing density of ash in stands (Figure 2A), which is contradictory, appears as an artefact of the progression of the dieback, as the trees were gradually dying off. Though presence of biological or physical barriers, as in the case of denser, yet mixed stands, can have the opposite effect limiting spread/development of the pathogen [30,31,32,33]. Nevertheless, stands with high ash density nowadays would indicate metapopulations with high resistance to the pathogen. The response of survival to time (Figure 2E) showed dieback of the studied population of ash to be continuous, as shown on a large scale by Coker et al. (2019) [78]. The survival has stabilized ca. 16 years since the supposed beginning of the dieback, yet remains at a low level, indicating further constant reduction in abundance of ash, corresponding to relatively low mortality rates [78].

The overall negative effect of time (Figure 2E), as well as relationships with tree size (Figure 2A), imply that ash is not likely to restore its economic potential [20], though scattered trees will likely continue their struggle, providing some ecological functions as an admixture species [2,5]. Nevertheless, the positive response of survival to decreasing competition (at low stand densities), as well as response to relative height (Figure 2C,D) implies positive effects of management (e.g., tending; [5,11,12]), which might facilitate survival and development of the most resistant metapopulations [7,9,10,16]. The complex effects of tree- and stand-level variables (Figure 2) imply that the observed relationships should be extrapolated cautiously, and regionally specific tweaking of management could be necessary to facilitate long-term perspectives of ash [27,34]. Considering the adaptive potential of the northern haplotype [10,40], as indicated by its geographic range and various conditions inhabited [44], hopefully adjusted management might also provide time needed for natural adaptation to proceed [6,7,13]. Improvements of resistance and adaptability of common ash appear particularly topical, considering the invasion of Emerald ash borer, which is also considered as a major threat to the existence of tree species [65,79]. For this, any facilitation of regeneration of the most resistant genotypes of ash is crucial [12,16].

5. Conclusions

Considering the devastating effect of dieback on the abundance of ash, stands are undergoing gradual transformation, with other deciduous species replacing ash, similarly as observed across Europe. Although during the first 10 years of dieback relatively low mortality rates were observed, during 2016–2020 it increased as the most tolerant individuals started to fail. Nevertheless, local re-establishment of ash has been evidenced by the ongoing recruitment of samplings into the larger diameter classes, likely due to coinciding synergy of local adaptation and favorable site conditions, hopefully indicating potential for adaptation of trees. Furthermore, the observed responses of survival to stand- and tree-level variables indicated potential to improve the survival of ash at least locally via management (tending), providing time for natural resistance to evolve.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/12/3/340/s1, Table S1: Changes in the mean density (individuals per hectare) of living and dead trees with diameter at breast height ≥ 6 cm in the 15 permanent sampling plots in common ash stands in Latvia under ash dieback during the period of 2005–2020.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and I.M.; Methodology, I.M. and Ā.J.; Software, R.M.; Validation, R.M., Ā.J. and I.M.; Formal Analysis, R.M..; Investigation, I.M.; Resources, Ā.J.; Data Curation, I.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.M. and I.M.; Writing—Review and Editing, R.M. and Ā.J.; Visualization, R.M.; Supervision, Ā.J.; Project Administration, Ā.J.; Funding Acquisition, Ā.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the ERA-NET SUMFOREST project REFORM “Resilience of forest mixtures”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Māris Laiviņs who provided data from the initial surveys.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gross, A.; Holdenrieder, O.; Pautasso, M.; Queloz, V.; Sieber, T.N. Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus, the causal agent of European ash dieback. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014, 15, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pautasso, M.; Aas, G.; Queloz, V.; Holdenrieder, O. European ash (Fraxinus excelsior) dieback—A conservation biology challenge. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 158, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumanová, E.; Romportl, D.; Havrdová, L.; Zahradník, D.; Pešková, V.; Černý, K. Predicting ash dieback severity and environmental suitability for the disease in forest stands. Scand. J. For. Res. 2019, 34, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfmeier, A.; Haldan, K.L.; Beckmann, L.-M.; Behrens, M.; Rotert, J.; Schrautzer, J. Ash Dieback and Its Impact in Near-Natural Forest Remnants—A Plant Community-Based Inventory. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.J.; Beaton, J.K.; Bellamy, P.E.; Broome, A.; Chetcuti, J.; Eaton, S.; Ellis, C.J.; Gimona, A.; Harmer, R.; Hester, A.J.; et al. Ash dieback in the UK: A review of the ecological and conservation implications and potential management options. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 175, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkis, A.; Bakys, R.; Stein Åslund, M.; Davydenko, K.; Elfstrand, M.; Stenlid, J.; Vasaitis, R. Identifying Fraxinus excelsior tolerant to ash dieback: Visual field monitoring versus a molecular marker. For. Pathol. 2020, 50, e12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stener, L.G. Genetic evaluation of damage caused by ash dieback with emphasis on selection stability over time. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 409, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, M.; Nguyen, D.; Stener, L.G.; Stenlid, J.; Skovsgaard, J.P. Ash and ash dieback in Sweden: A review of disease history, current status, pathogen and host dynamics, host tolerance and management options in forests and landscapes. In Dieback of European Ash (Fraxinus spp.): Consequences and Guidelines for Sustainable Management; Vasaitis, R., Enderle, R., Eds.; SLU: Uppsala, Sweden, 2017; pp. 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, L.V.; Nielsen, L.R.; Hansen, J.K.; Kjær, E.D. Presence of natural genetic resistance in Fraxinus excelsior (Oleraceae) to Chalara fraxinea (Ascomycota): An emerging infectious disease. Heredity 2011, 106, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliura, A.; Lygis, V.; Marčiulyniene, D.; Suchockas, V.; Bakys, R. Genetic variation of Fraxinus excelsior half-sib families in response to ash dieback disease following simulated spring frost and summer drought treatments. IForest 2015, 9, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrdová, L.; Zahradník, D.; Romportl, D.; Pešková, V.; Černý, K. Environmental and Silvicultural Characteristics Influencing the Extent of Ash Dieback in Forest Stands. Balt. For. 2017, 23, 168–182. [Google Scholar]

- Skovsgaard, J.P.; Wilhelm, G.J.; Thomsen, I.M.; Metzler, B.; Kirisits, T.; Havrdová, L.; Enderle, R.; Dobrowolska, D.; Cleary, M.; Clark, J. Silvicultural strategies for Fraxinus excelsior in response to dieback caused by Hymenoscyphus fraxineus. Forestry 2017, 90, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, L.V.; Nielsen, L.R.; Collinge, D.B.; Thomsen, I.M.; Hansen, J.K.; Kjaer, E.D. The ash dieback crisis: Genetic variation in resistance can prove a long-term solution. Plant Pathol. 2014, 63, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, E.D.; McKinney, L.V.; Nielsen, L.R.; Hansen, L.N.; Hansen, J.K. Adaptive potential of ash (Fraxinus excelsior ) populations against the novel emerging pathogen Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus. Evol. Appl. 2012, 5, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygis, V.; Prospero, S.; Burokiene, D.; Schoebel, C.N.; Marciulyniene, D.; Norkute, G.; Rigling, D. Virulence of the invasive ash pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus in old and recently established populations. Plant Pathol. 2016, 66, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semizer-Cuming, D.; Finkeldey, R.; Nielsen, L.R.; Kjær, E.D. Negative correlation between ash dieback susceptibility and reproductive success: Good news for European ash forests. Ann. For. Sci. 2019, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakys, R. Dieback of Fraxinus excelsior in the Baltic Sea Region Associated Fungi, Their Pathogenicity and Implications for Silviculture; SLU: Uppsala, Sweden, 2013; ISBN 9789157677679. [Google Scholar]

- Kirisits, T.; Kritsch, P.; Kräutler, K.; Matlakova, M.; Halmschlager, E. Ash dieback associated with Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus in forest nurseries in Austria. J. Agric. Ext. Rural Dev. 2012, 4, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygis, V.; Bakys, R.; Gustiene, A.; Burokiene, D.; Matelis, A.; Vasaitis, R. Forest self-regeneration following clear-felling of dieback-affected Fraxinus excelsior: Focus on ash. Eur. J. For. Res. 2014, 133, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petucco, C.; Lobianco, A.; Caurla, S. Economic Evaluation of an Invasive Forest Pathogen at a Large Scale: The Case of Ash Dieback in France. Environ. Model. Assess. 2020, 25, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klesse, S.; von Arx, G.; Gossner, M.M.; Hug, C.; Rigling, A.; Queloz, V. Amplifying feedback loop between growth and wood anatomical characteristics of Fraxinus excelsior explains size-related susceptibility to ash dieback. Tree Physiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosdidier, M.; Scordia, T.; Ioos, R.; Marçais, B. Landscape epidemiology of ash dieback. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakys, R.; Vasaitis, R.; Skovsgaard, J.P. Patterns and severity of crown dieback in young even-aged stands of european ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) in relation to stand density, bud flushing phenotype, and season. Plant Prot. Sci. 2013, 49, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.M.; Galambao, M.; Rowntree, J.; Goodhead, I.; Hall, J.; O’Brien, D.; Atkinson, N.; Antwis, R.E. Complex associations between cross-kingdom microbial endophytes and host genotype in ash dieback disease dynamics. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matisone, I.; Matisons, R.; Jansons, Ā. Health condition of european ash in young stands of diverse composition. Balt. For. 2019, 25, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Thomsen, I.M. Jahrbuch der Baumpflege 2014; Haymarket Media: London, UK, 2014; pp. 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann, V.; Nagy, N.E.; Hietala, A.M.; Børja, I.; Solheim, H. Progression of ash dieback in Norway related to tree age, disease history and regional aspects. Balt. For. 2017, 23, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, M.; Woodcock, P.; Quine, C.P. Dealing with dieback: Forest manager attitudes towards developing resistant ash trees in the United Kingdom. Forestry 2019, 92, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderle, R.; Metzler, B.; Riemer, U.; Kändler, G. Ash Dieback on Sample Points of the National Forest Inventory in South-Western Germany. Forests 2018, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosawang, C.; Amby, D.B.; Bussaban, B.; McKinney, L.V.; Xu, J.; Kjær, E.D.; Collinge, D.B.; Nielsen, L.R. Fungal communities associated with species of Fraxinus tolerant to ash dieback, and their potential for biological control. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautasso, M.; Holdenrieder, O.; Stenlid, J. Susceptibility to Fungal Pathogens of Forests Differing in Tree Diversity. In Forest Diversity and Function; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Jactel, H.; Brockerhoff, E.; Duelli, P. A Test of the Biodiversity-Stability Theory: Meta-analysis of Tree Species Diversity Effects on Insect Pest Infestations, and Re-Examination of Responsible Factors. In Forest Diversity and Function; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 235–262. [Google Scholar]

- Loreau, M.; Naeem, S.; Inchausti, P.; Bengtsson, J.; Grime, J.P.; Hector, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Huston, M.A.; Raffaelli, D.; Schmid, B.; et al. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: Current knowledge and future challenges. Science 2001, 294, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrowolska, D.; Hein, S.; Oosterbaan, A.; Wagner, S.; Clark, J.; Skovsgaard, J.P. A review of European ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.): Implications for silviculture. Forestry 2011, 84, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosdidier, M.; Ioos, R.; Marçais, B. Do higher summer temperatures restrict the dissemination of Hymenoscyphus fraxineus in France? For. Pathol. 2018, 48, e12426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, W.; Kowalski, T.; Kraj, W.; Zachara, T.; Lukaszewicz, J.; Paluch, R.; Nowakowska, J.A.; Oszako, T. Ash dieback in Poland—history of the phenomenon and possibilities of its limitation. In Dieback of European Ash (Fraxinus spp.): Consequences and Guidelines for Sustainable Management; Vasaitis, R., Enderle, R., Eds.; SLU: Uppsala, Sweden, 2017; pp. 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Chandelier, A.; Gerarts, F.; San Martin, G.; Herman, M.; Delahaye, L. Temporal evolution of collar lesions associated with ash dieback and the occurrence of Armillaria in Belgian forests. For. Pathol. 2016, 46, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietala, A.M.; Timmermann, V.; BØrja, I.; Solheim, H. The invasive ash dieback pathogen Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus exerts maximal infection pressure prior to the onset of host leaf senescence. Fungal Ecol. 2013, 6, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, V.; Børja, I.; Hietala, A.M.; Kirisits, T.; Solheim, H. Ash dieback: Pathogen spread and diurnal patterns of ascospore dispersal, with special emphasis on Norway. EPPO Bull. 2011, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuertz, M.; Fineschi, S.; Anzidei, M.; Pastorelli, R.; Salvini, D.; Paule, L.; Frascaria-Lacoste, N.; Hardy, O.J.; Vekemans, X.; vendramin, G.G. Chloroplast DNA variation and postglacial recolonization of common ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) in Europe. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 3437–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavin, L.; Jump, A.S. Highest drought sensitivity and lowest resistance to growth suppression are found in the range core of the tree Fagus sylvatica L. not the equatorial range edge. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, E.; Lauder, J.; Musser, C.; Stathos, A.; Shu, M. The genetics of drought tolerance in conifers. New Phytol. 2017, 216, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dering, M.; Kosiński, P.; Wyka, T.P.; Pers-Kamczyc, E.; Boratyński, A.; Boratyńska, K.; Reich, P.B.; Romo, A.; Zadworny, M.; Żytkowiak, R.; et al. Tertiary remnants and Holocene colonizers: Genetic structure and phylogeography of Scots pine reveal higher genetic diversity in young boreal than in relict Mediterranean populations and a dual colonization of Fennoscandia. Divers. Distrib. 2017, 23, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Matesanz, S.; Guilhaumon, F.; Araújo, M.B.; Balaguer, L.; Benito-Garzón, M.; Cornwell, W.; Gianoli, E.; Kleunen, M.; Naya, D.E.; et al. The effects of phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation on forecasts of species range shifts under climate change. Ecol. Lett. 2014, 17, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matisone, I.; Matisons, R.; Laiviņš, M.; Gaitnieks, T. Statistics of ash dieback in Latvia. Silva Fenn. 2018, 52, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepins, K.; Liepins, J.; Matisons, R. Growth Patterns and Spatial Distribution of Common Ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) in Latvia. Proc. Latv. Acad. Sci. Sect. B Nat. Exact Appl. Sci. 2016, 70, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, M.; Nguyen, D.; Marčiulyniene, D.; Berlin, A.; Vasaitis, R.; Stenlid, J. Friend or foe? Biological and ecological traits of the European ash dieback pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus in its native environment. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Hosoya, T.; Baral, H.O.; Hosaka, K.; Kakishima, M. Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus, the correct name for Lambertella albida reported from Japan. Mycotaxon 2012, 122, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.A.; Alexander, H.M.; Davidson, J.; Campbell, F.T.; Burdon, J.J.; Sniezko, R.; Brasier, C. Increasing forest loss worldwide from invasive pests requires new trade regulations. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenlid, J.; Oliva, J.; Boberg, J.B.; Hopkins, A.J.M. Emerging Diseases in European Forest Ecosystems and Responses in Society. Forests 2011, 2, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, S.E.; Hooten, M.B.; Rizzo, D.M.; Meentemeyer, R.K. Forest species diversity reduces disease risk in a generalist plant pathogen invasion. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.; Gilligan, C.A.; Kleczkowski, A.; Hanley, N.; Whalley, A.E.; Healey, J.R. The Effect of Forest Management Options on Forest Resilience to Pathogens. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2020, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pušpure, I.; Gerra -Inohosa, L.; Arhipova, N. Quality assessment of European ash Fraxinus excelsior L. genetic resource forests in Latvia. In Proceedings of the Annual 21st International Scientific Conference Research for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 13–15 May 2015; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, I.; Jones, P.D.; Osborn, T.J.; Lister, D.H. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations—The CRU TS3.10 Dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avotniece, Z.; Klavins, M.; Rodinovs, V. Changes of extreme climate events in Latvia. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2012, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2011, 73, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.H.; Duffy, P.A.; Mann, D.H. Nonlinear responses of white spruce growth to climate variability in interior Alaska. Can. J. For. Res. 2013, 43, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria; Available online: http://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, V.; Senström, A. Ash Dieback—A continuing threat to veteran ash trees? In Dieback of European ash (Fraxinus spp.)—Consequences and Guidelines for Sustainable Management; Vasaitis, R., Enderle, R., Eds.; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 2017; pp. 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Pušpure, I.; Matisons, R.; Laiviņš, M.; Gaitnieks, T.; Jansons, J. Natural Regeneration of Common Ash in Young Stands in Latvia. Baltic For. 2017, 23, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Puspure, I.; Laivins, M.; Matisons, R.; Gaitnieks, T. Understory Changes in Fraxinus excelsior Stands in Response to Dieback in Latvia. Proc. Latv. Acad. Sci. Sect. B Nat. Exact Appl. Sci. 2016, 70, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Matisons, R.; Puriņa, L.; Adamovičs, A.; Robalte, L.; Jansons, Ā. European beech in its northeasternmost stands in Europe: Varying climate-growth relationships among generations and diameter classes. Dendrochronologia 2017, 45, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, A.; Ray, D.; Mitchell, R.; Harmer, R. Responding to ash dieback (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus) in the UK: Woodland composition and replacement tree species. For. An Int. J. For. Res. 2019, 92, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, B.; Kilgore, J. Forest Regeneration Following Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairemaire) Enhances Mesophication in Eastern Hardwood Forests. Forests 2018, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turczański, K.; Dyderski, M.K.; Rutkowski, P. Ash dieback, soil and deer browsing influence natural regeneration of European ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.; Fuentes-Utrilla, P.; Gil, L.; Witzell, J. Ecological factors in Dutch elm disease complex in Europe-a review. Ecol. Bull. 2010, 53, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin, C.R.; Lorimer, C.G. Trajectories and resilience of stand structure in response to variable disturbance severities in northern hardwoods. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 365, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.H.; Marks, P.L. Intact forests provide only weak resistance to a shade-tolerant invasive Norway maple (Acer platanoides L.). J. Ecol. 2006, 94, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Jagodziński, A.M. Low impact of disturbance on ecological success of invasive tree and shrub species in temperate forests. Plant Ecol. 2018, 219, 1369–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfving, B.; Kiviste, A. Construction of site index equations for Pinus sylvestris L. using permanent plot data in Sweden. For. Ecol. Manag. 1997, 98, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petritan, A.M.; Von Lupke, B.; Petritan, I.C. Effects of shade on growth and mortality of maple (Acer pseudoplatanus), ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and beech (Fagus sylvatica) saplings. Forestry 2007, 80, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.J. Wind as a natural disturbance agent in forests: A synthesis. Forestry 2013, 86, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csilléry, K.; Kunstler, G.; Courbaud, B.; Allard, D.; Lassègues, P.; Haslinger, K.; Gardiner, B. Coupled effects of wind-storms and drought on tree mortality across 115 forest stands from the Western Alps and the Jura mountains. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 5092–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krisans, O.; Matisons, R.; Rust, S.; Burnevica, N.; Bruna, L.; Elferts, D.; Kalvane, L.; Jansons, A. Presence of root rot reduces stability of Norway spruce (Picea abies): Results of static pulling tests in Latvia. Forests 2020, 11, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X. Effects of social position and competition on tree transpiration of a natural mixed forest in Chongqing, China. Trees Struct. Funct. 2019, 33, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.; Monnier, Y.; Santonja, M.; Gallet, C.; Weston, L.A.; Prévosto, B.; Saunier, A.; Baldy, V.; Bousquet-Mélou, A. The Impact of Competition and Allelopathy on the Trade-Off between Plant Defense and Growth in Two Contrasting Tree Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, T.L.R.; Rozsypálek, J.; Edwards, A.; Harwood, T.P.; Butfoy, L.; Buggs, R.J.A. Estimating mortality rates of European ash (Fraxinus excelsior) under the ash dieback (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus) epidemic. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenta, V.; Moser, D.; Kuttner, M.; Peterseil, J.; Essl, F. A High-Resolution Map of Emerald Ash Borer Invasion Risk for Southern Central Europe. Forests 2015, 6, 3075–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).