The Institutional Structure of Land Use Planning for Urban Forest Protection in the Post-Socialist Transition Environment: Serbian Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.1.1. Land Use Planning

1.1.2. Urban Forest Management

1.1.3. Concept of Institutional Transformation

- (a)

- The first is the concept of governance, which is the most appropriate at the macro-level as it involves society as a whole and is linked to constitutional and legal amendments. This is the level of institutional design to which belong requirements for institutional change encountered by Serbia in its EU accession process.

- (b)

- The second concept is that of coordination, at the meso-level, which pertains to the domain of planning and comprises procedures which facilitate the development and implementation of policies, programmes, projects and plans associated with professional planners’ fields of practice.

- (c)

- The third is the concept of agency, which occurs at the micro-level and involves intra-organisational design, the ordering of smaller working units and groups and the processes and interactions within and between them. This level directly entails managing planning processes and policy, the plan or project implementation [22].

2. Materials and Methods

- The macro-level entails assessing the regulatory framework for the development planning system related to urban forest management in Serbia from two aspects:

- (a)

- Overview and assessment of the institutional and legal framework for urban forest protection standards at all levels of administrative organisation: national, regional and local. In this assessment the position of urban forest protection standards within basic land use planning documents is also included.

- (b)

- Overview and assessment of the value framework for urban forest protection in national policy documents.This phase of the research relies on reviewing and analysing both the primary literature (laws, strategies and other public documents) and secondary sources dealing with issues of the planning system for urban forest protection.

- The meso-level looks at the procedures for cooperation between institutions of the land use planning process on the local level, related to urban forest management in Serbia. Institutions are observed from the national to the local levels through the lens of multilevel governance. The focus is on the procedures for collaboration between institutions in the process of the ‘General zoning plan’ production, as well as policy-making procedures, and is observed in two aspects:

- (a)

- Identification of the organisational structure, with particular attention to the position, powers and roles of the relevant institutions.

- (b)

- Arrangements for collaboration that includes insight into both the horizontal and the vertical levels.This segment of the research relies primarily on a review of primary literature that sets out organisational powers while also considering secondary documents devoted to how land use planning and urban forest management policies are made.

- (a)

- Medium-sized cities (in order to avoid the overly complex problems that are characteristic of large cities).

- (b)

- The dominant planning agenda is ‘saving urban forests’. Bor is a town where the urban environment is exposed to the impacts of copper and gold mines situated in the immediate vicinity, and Vrnjačka Banja is an urban environment purposefully developed as a spa.

- (c)

- The planning processes started after the year 2000, following the introduction of Serbia’s new socioeconomic framework.

3. Results

3.1. Macro-Level: Regulatory Framework for Development Planning System Related to Urban Forest Management in Serbia

3.1.1. Institutional and Legal Framework for Urban Forest Protection Standards

3.1.2. Value Framework for Urban Forest Protection in Serbia

3.2. Meso-Level: Formal Cooperation Procedures between Institutions for Land Use Planning Related to Urban Forest Management in Serbia

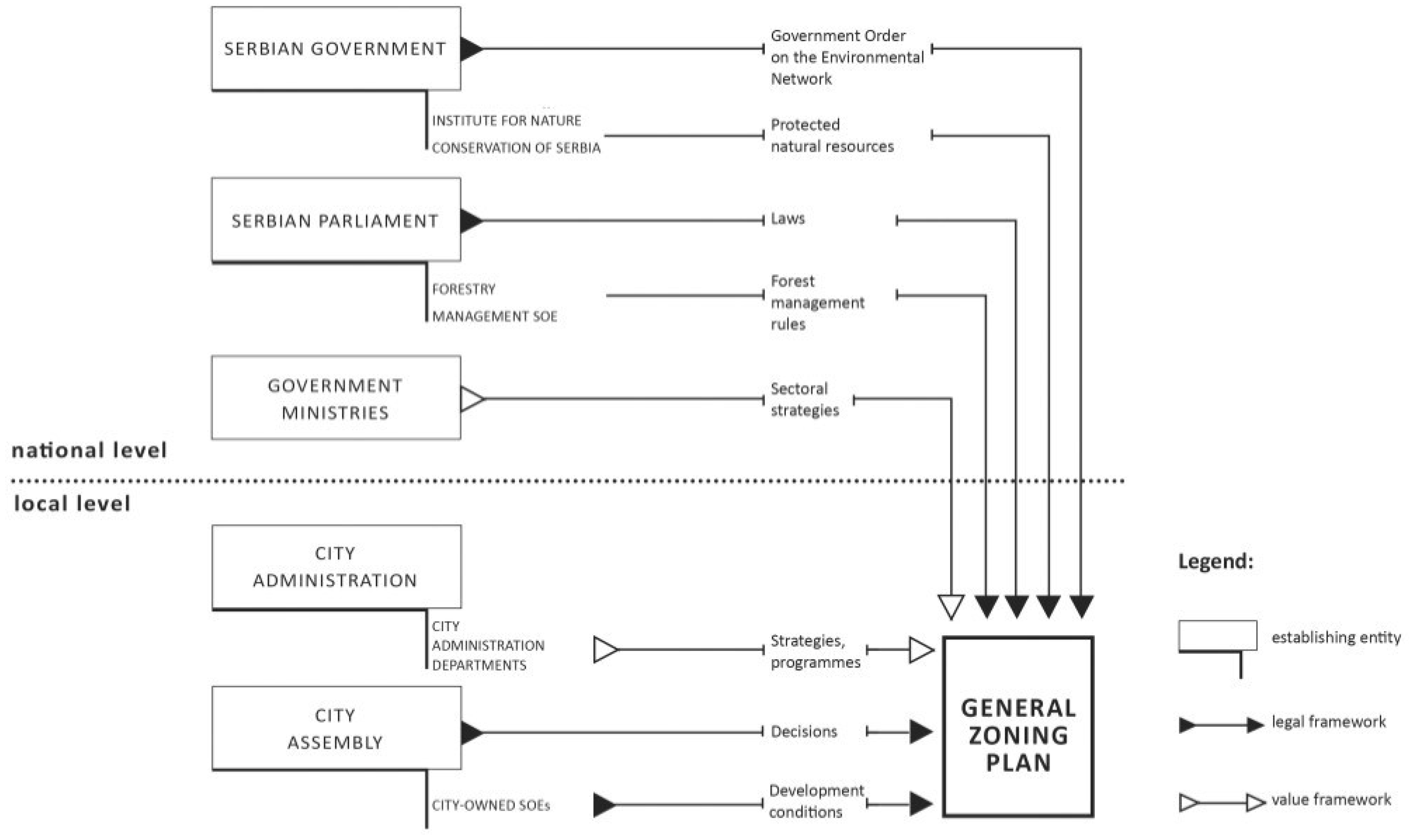

3.2.1. Organisational Structure

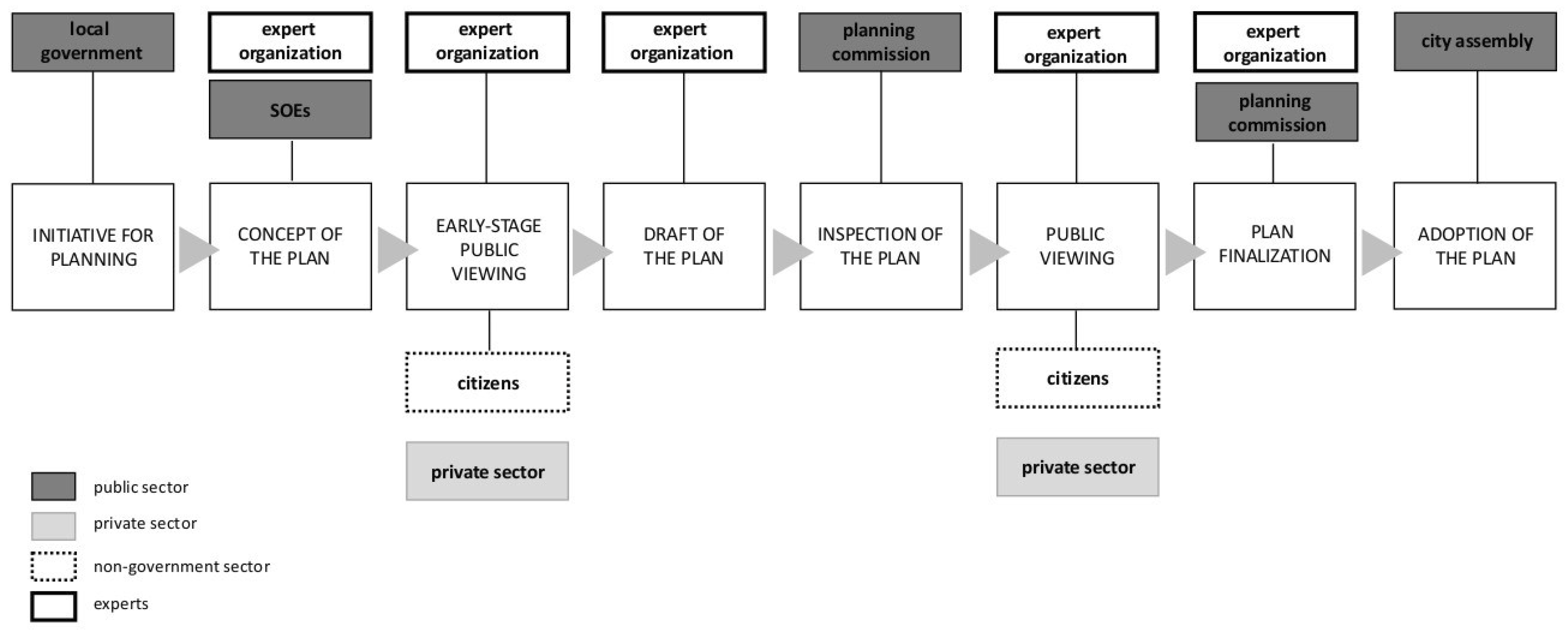

3.2.2. Arrangements for Collaboration

3.3. Micro-Level: Activities in Land Use Planning Practice

- (a)

- The formal influence is implemented through

- plans of higher order,

- conditions of institutes for environmental protection and

- conditions of SOEs for managing forest land;

- (b)

- The informal influence is implemented through

- capacity of experts in relation to urban forest management and preservation in various positions of the planning procedure—local councillor, expert responsible for a plan creation, expert in the planning commission, expert from the civil sector and expert from the private sector; and

- capacity of nonexpert stakeholders in relation to urban forest management and preservation in various positions of the planning procedure—local councillor, civil sector and private sector.

3.3.1. Examples of the Land Use Planning Practice Related to Urban Forest Management in Serbia

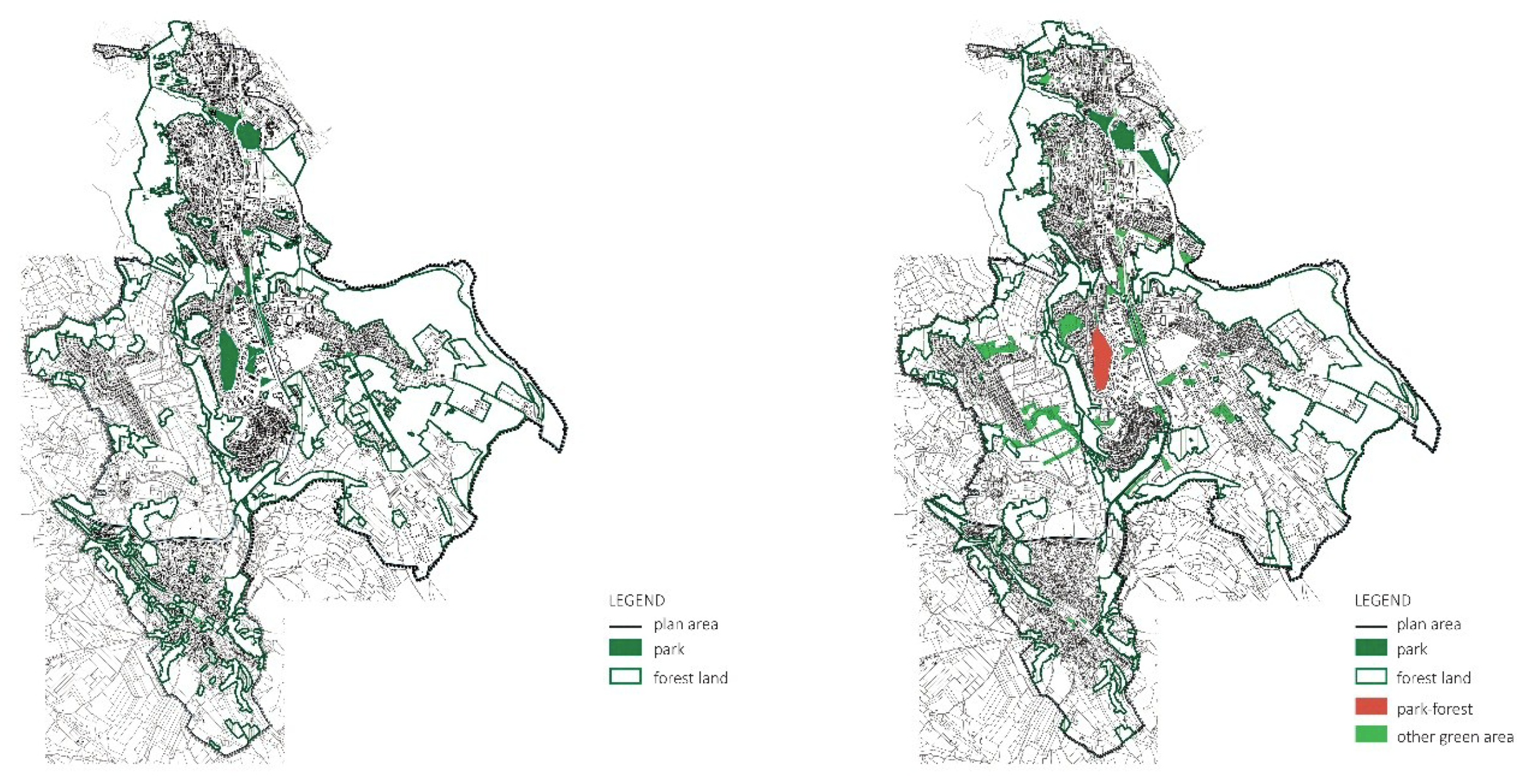

General Zoning Plan for the Town of Vrnjačka Banja

General Zoning Plan for the Town of Bor

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- (a)

- The shift in the economic system to embrace open market principles, directly leading to altered ownership of land and, thereby, to a new balance of power in society. This has brought about a fundamental change in perspectives of public property and promoted the diversification of interests related to land use. While it was formerly beyond question, public interest, as a category defined by ideological norms, is now a matter of political agreement that reflects the balance of power in society.

- (b)

- Acceptance of the global value framework and the principle of sustainability as the dominant development concept, which occasioned the development of horizontal and vertical coordination mechanisms at all levels of institutional structure. This is significantly different in relation to top-down decision-making practice that was dominant in a socialist society, where communication mechanisms were exclusively in the function of carrying out the decisions made at the highest level.

- (c)

- Acceptance of European integration, where a primary value concept is the principle of subsidiarity, whereby responsibility for decision-making on shared issues is transferred to the lowest possible tier of social organisation. It has introduced democratic dialogue as a means of determining the value orientation of future spatial development. This presents a major challenge for local authorities that should demonstrate the ability to carry out democratic dialogue within the community and the choice of development goals.

- (a)

- Regulatory structure and the value framework of public policies. This aspect of institutional analysis is aimed at examining the macro-level, which is in Serbia determined by significant macro-societal processes that take place due to the adoption of national and supranational constitutions [22]. It includes two aspects: (a) an institutional and legal framework for urban forest protection standards and (b) a value framework for urban forest protection.Serbia’s planning system is hierarchically organised, from higher to lower levels of governance. Legislative changes have aimed at reducing the number of planning levels to promote efficiency and effectiveness in implementing plans. However, planning has failed to keep up with the pace of legislative change, which has in practice led to unclear planning procedures and misalignment between the outcomes of planning at various spatial levels. These circumstances have caused confusion between the national, regional and local levels as to their respective powers and roles.Further, the practice of land use planning related to urban forest management is subject to a variety of laws enacted by administrative authorities in numerous sectors. One issue here is the lack of alignment between urban forest protection standards introduced by the various regulations, which has caused problems with interpretation and implementation at the local level.On the other hand, the value framework for urban forest protection is formally implemented through the legislative framework and the standards for protection envisaged by it. A major issue here is the set of policy documents the implementation of which is not formalised and is therefore not mandatory. The multitude of formal and informal policy documents at the national level, not sufficiently aligned with one another, prevent both the establishment and the implementation of a clear value framework. As a basic drawback, the absence of a terminological framework and the identification of urban forests as a separate category of urban green land are observed, leaving at the local level a space for different interpretations, as is shown in the cases of the General zoning plans of Vrnjačka Banja and Bor. In addition, the underdeveloped capacities of local SOEs, due to the lack of expert profiles in the formation of employees, as well as the burden on the public service of many utilities, represent an obstacle in the formulation of requirements as well as the implementation of protection measures.Thus, as was illustrated in both of the General Zoning Plans of Vrnjačka Banja and Bor, standards defined on the national level serve as guidelines for particular land use planning processes; however, LUPUFP is not yet recognised as a concept.Consequently, the key components of the regulatory framework for the establishment of the LUPUFP system are

- Retaining the hierarchy of the planning system;

- Setting clear planning procedures and defining expected outcomes of planning at various spatial levels;

- Harmonising different regulations that envisage urban forest protection standards;

- Establishing a clear relationship between formal and informal policy documents;

- Mutual alignment of the multitude of policy documents;

- Formalising relationships between legally binding and nonbinding policies at the national and local governance levels.

- (b)

- Procedures for cooperation between institutions. The next level of institutional analysis (the meso-level) involves planning and implementation structures and processes [22]. Serbia’s traditional hierarchical planning system, which entails complex inter-organisational networks, requires cooperation at the horizontal and vertical levels aimed at the development and implementation of policies, programmes, projects and plans. The top-down approach, which emphasised the national decision-making level and an expert-driven approach to policy-making, is slowly opening up to bottom-up initiatives and the acknowledgment of particular interests in decision-making. This has been accompanied by a new set of regulatory reforms that aim at decentralising public administration and placing responsibility for making spatial planning decisions at the local level. This type of institutional transformation entails a reform process wherein the regulatory system is carefully harmonised both horizontally and vertically. The preconditions for these changes are a clear political orientation and the provision of appropriate professional capacity. As such, institutional design must be based on firm foundations, including institutions and regulations, which both define policies for urban forest protection and ensure decision-making procedures aimed at safeguarding the public interest.From the urban forest management perspective, the institutional structure is strictly divided between the national and the local level of governance. Each institutional level possesses a distinct unit charged with issues of nature conservation, including forests, whereby the communication between them is very weak. Also, the strict sectoral division between governance units at the same level poses a problem for horizontal communication. As was illustrated in cases of the General Zoning Plans of Vrnjačka Banja and Bor, there is a noticeable absence of horizontal communication between the sectors dealing with the ”saving urban forest” agenda, as the requirements for defining planning measures such as “restrictions”, “protection zones” and protection conditions” are not obligatory. This clearly shows that, for example, climate change issues, drinking water protection, energy efficiency, healthy environment, etc. are irreconcilable, and therefore they are dependent of the expertise of the organisations involved in the development of the plan as well as the knowledge of the local community.The value framework for the agenda of saving urban forests requires firm regulations for stakeholder involvement in making decisions on urban forests, indicating that various control mechanisms are necessary. The weaknesses of such a system lie in the rigidity of its mechanisms and their uncritical application in locally specific situations. Implementation of the public policies and safeguarding the adopted value framework is contributed by units specialised in nature and forest protection at all levels.As was illustrated in Vrnjačka Banja and Bor, bottom-up initiatives for forest protection and development from the local level that are recognised within land use planning processes, such as particular local decisions, reflect the adjustment of the institutional structure in order to promote the concept of LUPUFP.Consequently, the key components for the establishment of the LUPUFP system related to the procedures for cooperation between institutions are

- Strengthening vertical coordination between specialised nature and forest protection units at the national as well as local levels;

- Establishing procedures and mechanisms for horizontal communication between sectors at the same level of governance;

- Establishing procedures and mechanisms for bottom-up communication by decision-makers;

- Creating preconditions for efficient multi-stakeholder cooperation;

- Establishing firm regulations to control the impact of market forces;

- Defining legal procedures that acknowledge control mechanisms;

- Ensuring more flexibility in the application of control mechanisms in locally specific situations;

- Retaining specialised units and their instruments for implementing nature and forest protection instruments;

- Establishing mechanisms for horizontal and vertical coordination of policy implementation instruments.

- (c)

- Activities in land use planning practice. This level of analysis pertains to intra-organisational design, addressing organisational subunits and small semiformal or informal social units, processes and interactions [22]. Also, it directly examines the extent of stakeholder participation related to the legal framework, the effectiveness of processes, and the space for the involvement of civil society [36] in relation to urban forest management.Land use planning at the local level in Serbia in general is noticeably top-down oriented, with strict control conducted by public sector, and mainly subordinate to the attainment of public sector interests. The participation of stakeholders from the private and civil sectors is partial and insufficient. The role of expert organisations does not enjoy a sufficiently clear position in the decision-making system. Substantial responsibility—and power—is given to the planning commission as an expert body of the local government. Accordingly, their position is sensitive to the influence of various interests. Furthermore, the structure of the commission does not include experts from the domain of urban forest management.As was illustrated in the example of the General zoning plan of Vrnjačka Banja, the formal institutional framework, particularly in the domain of top-down coordination and standards for protection, serves as a base for urban forest protection that was recognised as a crucial resource for further spa protection and development.In the example of Bor, where urban forest protection is not specially required outside of the formal standards, the informal institutional structure gives space for informal institutional actions for urban forest protection and bottom-up initiatives that are in line with the requirement for ‘fostering pro-environmental behaviours’.Consequently, the key components for the establishment of the LUPUFP system related to the activities in the land use planning practice are

- Establishing collaborative planning, which entails informed decision-making about the directions of urban development at key stages of plan production;

- Clarifying the roles of experts in the decision-making system and ensuring their independence from political decision-making;

- Clearly defining policies and regulatory mechanisms at the national level;

- Standardising the various categories of land use at the national level;

- Retaining mechanisms that acknowledge the regulatory norms and hierarchy of the planning system;

- Harmonising regulations across various sectors;

- Strengthening the positions and capacities of local public sector experts;

- Establishing a clear methodology for the development and content of urban plans.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution A/RES/70/1; United Nation: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2018).

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN HABITAT). New Urban Agenda. A/RES/71/256. United Nations, 2017. Available online: http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO UN). Urban and Peri-Urban Forestry-Definition. Available online: http://www.fao.org/forestry/urbanforestry/87025/en/ (accessed on 22 December 2018).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Guidelines on Urban and Peri-Urban Forestry; FAO Forestry Paper No. 178; Salbitano, F., Borelli, S., Conigliaro, M., Chen, Y., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Edreny, T. Strategically growing the urban forest will improve our world. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurokawa, H.K. Sustainability and the Urban Forest: An Ecosystem Services Perspective. Nat. Resour. J. 2011, 51, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhou, W.; Cao, F.; Wang, G. Effects of Spatial Pattern of Forest Vegetation on Urban Cooling in a Compact Megacity. Forests 2019, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. Assessing Urban Forest Structure, Ecosystem Services, and Economic Benefits on Vacant Land. Sustainability 2016, 8, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W. Ecosystem services and valuation of urban forests in China. Cities 2009, 26, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, B.S.; Chen, J.; Wu, S.R.; Zhou, P.; Shirkey, G. Does Plant Knowledge within Urban Forests and Parks Directly Influence Visitor Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Forests 2018, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curitiba Declaration on Cities and Biodiversity; Curitiba, Brazil. 2007. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/city/mayors-01/mayors-01-declaration-en.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2018).

- United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (UNCHS). An Urbanizing World: Global Report on Human Settlements; Oxford University Press for UNCHS: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baycan-Levent, T.; Nijkamp, P. Planning and Management of Urban Green Spaces in Europe: Comparative Analysis. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2009, 135, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolin, U.J. Planning Systems as Institutional Technologies: A Proposed Conceptualization and the Implications for Comparison. Plan. Pract. Res. 2012, 27, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L.; Alden, J.; Pires, A. (Eds.) The Changing Institutional Landscape of Planning; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Selznik, F. Institutionalism ‘Old’ and ‘New’. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 2, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. Elaborating the new institutionalism. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions; Rhodes, R.A.W., Binder, S.A., Rockman, B.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Institutionalist analysis, communicative planning, and shaping places. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1999, 19, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J. Models of Urban Governance: The Institutional Dimension of Urban Politics. Urban Aff. Rev. 1999, 34, 372–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.R. Institutional Transformation and Planning: From Institutionalization Theory to Institutional Design. Plan. Theory 2005, 4, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Scott, W. Institutional theory. In Encyclopedia of Social Theory; Ritzer, G., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 408–414. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.A. Historical Institutionalism in Rationalist and Sociological Perspective. In Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency and Power; Mahoney, J., Thelen, K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 204–225. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. An institutional model of the development process. J. Prop. Res. 1992, 9, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN HABITAT). Planning Sustainable Cities: Global Report on Human Settlements; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). The EU Compendium of Spatial Planning Systems and Policies; Office for Official Publications of the European Community: Luxembourg, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Spatial Planning: Key Instrument for Development and Effective Governance with Special Reference to Countries in Transition; United nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, L.D. Urban Development: The Logic of Making Plans; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Land-Use Planning Systems in the OECD: Country Fact Sheets; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Urban Sprawl in Europe: The Ignored Challenge; EEA Report No 10/2006; European Commission Joint Research Centre/European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sandström, C.; Lindkvist, A.; Öhman, K.; Nordström, E.M. Governing Competing Demands for Forest Resources in Sweden. Forests 2011, 2, 218–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buizer, M.; Van Herzele, A. Combining deliberative governance theory and discourse analysis to understand the deliberative incompleteness of centrally formulated plans. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 16, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). The EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities (CEC). White Paper, Adapting to Climate Change: Towards a European Framework for Action. 2009. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_threats/climate/docs/com_2009_147_en.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO UN). Framework for Assessing and Monitoring Forest Governance; The Program on Forests (PROFOR) and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, A.; De Vreese, R.; Johnston, M.; van den Bosch, C.C.K.; Sanesi, G. Urban forest governance: Towards a framework for comparing approaches. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laktić, T.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Stakeholder Participation in Natura 2000 Management Program: Case Study of Slovenia. Forests 2018, 9, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, L. Developing environmental governance research: The example of forest cover change studies. Environ. Conserv. 2011, 38, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggin, J.M.; Behagel, J.H.; Arts, B. Sustainable Forest Management and Social-Ecological Systems: An Institutional Analysis of Caatinga, Brazil. Forests 2017, 8, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. The Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change. Fit, Interplay, and Scale; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, H.; Marshall, R. Utilitarianism’s Bad Breath? A Re-Evaluation of the Public Interest Justification for Planning. Plan. Theory 2002, 1, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Lefsrud, L. Institutional theory, old and new. In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research; Mills, A.J., Durepos, G., Wiebe, E., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zeković, S. Urban land planning in Serbia. Arhitektura i Urbanizam 2002, 9, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Živanović Miljković, J. Urban Land Use regulation in Serbia: An analysis of its effects on property rights. In A Support to Urban Development Process; Bolay, J.C., Maričić, T., Zeković, S., Eds.; EPFL & IAUS: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018; pp. 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Nonić, D. Organisation and Operation of the Forestry Service; Univerzitet u Beogradu, Šumarski fakultet: Beograd, Serbia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Spatial Development (CSD). European Spatial Development Perspective: Towards a Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the European Union; Office for the Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard, R.A. Epilogue: Globalization and the city. In Change and Stability in Urban Europe; Anderson, H., Jorgensen, G., Joye, D., Ostendorf, W., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2001; pp. 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Pallagst, K.M.; Mercier, G. Urban and regional planning in Central and Eastern European countries–from EU requirements to innovative practices. In The Post-Socialist City: Urban form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Stanilov, K., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 473–490. [Google Scholar]

- Maruna, M.; Čolić, R.; Milovanović Rodić, D. A New Regulatory Framework as both an Incentive and Constraint to Urban Governance in Serbia. In A Support to Urban Development Process; Bolay, J.C., Maričić, T., Zeković, S., Eds.; EPFL & IAUS: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018; pp. 80–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stanilov, K. Urban planning and the challenges of post-socialist transformation. In The Post-Socialist City: Urban form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Stanilov, K., Ed.; Springer-GeoJournal Library: Dodrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Tsenkova, S. Urban Futures: Strategic planning in post-socialist Europe. In The Post-Socialist City: Urban form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Stanilov, K., Ed.; Springer-GeoJournal Library: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 447–471. [Google Scholar]

- Petovar, K. Professional Associations as an Actor in the Enactment of Spatial Planning Decisions. In Actors of Social Changes in Space: Spatial Transformation and Quality of Life in Croatia; SvirčićGotovac, A., Zlatar, J., Eds.; Institut za društvena istraživanja: Zagreb, Croatiam, 2012; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Vujošević, M.; Petovar, K. Public interest and actor strategies in urban and spatial planning. Sociologija 2006, 48, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlada RS (Vlada Republike Srbije) Pregovaračka poglavlja, Poglavlje 27: Životna sredina [Chapters of the Acquis. Chapter 27: Environment]; Pregovarački tim za vođenje pregovora o pristupanju Republike Srbije Evropskoj uniji. 2018. Available online: http://www.eu-pregovori.rs/srl/pregovaracka-poglavlja/poglavlje-27-zivotna-sredina/ (accessed on 26 December 2018).

- Council of Europe (CE). European Landscape Convention; European Treaty Series No. 176; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zakon o potvrđivanju Evropske konvencije o predelu [Law Ratifying the European Landscape Convention]. 2011. Available online: http://predelisrcasrbije.rs/dokumenta.html (accessed on 23 December 2018).

- Resolution H1: General Guidelines for the Sustainable Management of Forests in Europe. Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe, Helsinki. 1993. Available online: https://www.foresteurope.org/docs/MC/MC_helsinki_resolutionH1.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Zakon o potvrđivanju Konvencije o dostupnosti informacija, učešću javnosti u donošenju odluka i pravu na pravnu zaštitu u pitanjima životne sredine [Law Ratifying the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters]. 2009. Available online: https://www.poverenik.rs/sr-yu/me%C4%91unarodni-dokumenti/1735-zakon-o-potvrdjivanju-konvencije-o-dostupnosti-informacija-ucescu-javnosti-u-donosenju-odluka-i-pravu-na-pravnu-zastitu-u-pitanjima-zivotne-sredine.html (accessed on 11 September 2018).

- Lockwood, M. Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crnčević, T.; Manić, B.; Marić, I. Zeleni zidovi urbanih prostora u kontekstu klimatskih promena–pregled najnovijih okvira i iskustava [Green Walls of Urban Spaces in the Context of Climate Change-An Overview of the Latest Frameworks and Experiences]. Arhitektura i Urbanizam 2015, 41, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Crnčević, T.; Sekulić, M. Green Roofs in the Context of Climate Change-A review of recent experiences. Arhitektura i Urbanizam 2012, 36, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vujičić, D.; Tubić, Lj.; Todorović, D.; Šabanović, V.; Tutundžić, A.; Jeftović, A.; Jadžić, N. Sustainability of Green Space Legislation; Udruženje pejzažnih arhitekata Srbije: Beograd, Serbia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lukić, N. Urban Forests and Greening in the Republic of Serbia–Legal and Institutional Aspects. South-East Eur. For. 2013, 4, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gudurić, I.; Tomićević, J.; Konijnendijk, C.C. A comparative perspective of urban forestry in Belgrade, Serbia and Freiburg, Germany. Urban For. Green. 2011, 10, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakon o šumama [Forests Law]. 2015. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon-o-sumama-republike-srbije.html (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Zakon o planiranju i izgradnji [Planning and Construction Law]. 2018. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_planiranju_i_izgradnji.html (accessed on 22 Jun 2018).

- Trkulja, S.; Tošić, B.; Živanović, Z. Serbian Spatial Planning among Styles of Spatial Planning in Europe. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 1729–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, M.; Panagiotis, G.; Blotevogel, H. Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Uredba o ekološkoj mreži [Government Order on the Environmental Network]. 2010. Available online: http://www.zzps.rs/novo/kontent/stranicy/propisi_podzakonski_akti/uredba%20o%20ekoloskoj%20mrezi.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Uredba o režimima zaštite [Government Order on Safeguards]. 2012. Available online: http://www.zzps.rs/novo/kontent/stranicy/zastita_prirode_o_zasticenim_podrucjima/uredba_rezimi_zastite.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Zakon o prostornom planu Srbije [Law on Spatial Plan of Serbia]. 2010. Available online: https://www.mgsi.gov.rs/sites/default/files/ZAKON%20O%20PROSTORNOM%20PLANU%20RS%20OD%202010%20DO%202020.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Zakon o eksproprijaciji [Expropriation Law]. 2016. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_eksproprijaciji.html (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Zakon o javnoj svojini [Public Property Law]. 2018. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_javnoj_svojini.html (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Zakon o komunalnim delatnostima [Utilities Law]. 2018. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_komunalnim_delatnostima.html (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Zakon o zaštiti prirode [Nature Conservation Law]. 2018. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_zastiti_prirode.html (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Zakon o zaštiti životne sredine [Environmental Protection Law]. 2018. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_zastiti_zivotne_sredine.html (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Zakon o proceni uticaja na životnu sredinu [Environmental Impact Assessment Law]. 2009. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_proceni_uticaja_na_zivotnu_sredinu.html (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- Zakon o strateškoj proceni uticaja na životnu sredinu [Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment Law ]. 2010. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_strateskoj_proceni_uticaja_na_zivotnu_sredinu.html (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- Stojković, S. Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia; Službeni glasnik: Beograd, Srbija, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nacionalna strategija održivog korišćenja prirodnih resursa i dobara [National Strategy for Sustainable Use of Natural Resources]. 2012. Available online: http://www.zzps.rs/novo/kontent/stranicy/propisi_strategije/S_prirodnih%20resursa.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Nacionalna strategija održivog razvoja [National Sustainable Development Strategy]. 2008. Available online: http://www.zurbnis.rs/zakoni/Nacionalna%20strategija%20odrzivog%20razvoja.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Strategija razvoja šumarstva Republike Srbije [Serbia Forestry Development Strategy]. 2006. Available online: https://www.fornetserbia.com/doc/shared/Strategija_razvoja_sumarstva.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2019).

- Strategija biološke raznovrsnosti Republike Srbije za period 2011. do 2018. godine [Serbia Biodiversity Strategy, 2011 to 2018]. 2011. Available online: http://www.zzps.rs/novo/kontent/stranicy/propisi_strategije/strategija_bioloske_raznovrsnosti.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2019).

- Nacionalni program zaštite životne sredine [National Environmental Protection Programme]. 2010. Available online: http://www.zzps.rs/novo/kontent/stranicy/propisi_strategije/Nacionalni_program_zastite_%20zs.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Zakon o potvrđivanju Konvencije o biološkoj raznovrsnosti [Law Ratifying the Convention on Biological Diversity]. 2001. Available online: http://www.vojvodinasume.rs/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/sertifikacija/Zakon%20o%20potvrdjivanju%20KONVENCIJE%20O%20BIOLOSKOJ%20RAZNOVRSNOSTI.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Zakon o planiranju i izgradnji [Planning and Construction Law]. 2014. Available online: https://www.mgsi.gov.rs/sites/default/files/ZAKON%20O%20PLANIRANJU%20I%20IZGRADNJI%20PRECTEKST%202015.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Graovac, A.; Danilović Hristić, N.; Stefanović, N. Technical and logical methods for improving the process of urban planning in Serbia. Spatium 2017, 38, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plan generalne regulacije Vrnjačke Banje [General Zoning Plan of Vrnjačka Banja2016. Available online: http://vrnjackabanja.gov.rs/privreda/urbanizam/plan-generalne-regulacije?alphabet=lat (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Plan generalne regulacije gradskog naselja Bor [General Zoning Plan of the Town of Bor]. 2018. Available online: http://bor.rs/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Nacrt-Bor-Knjiga-I-Planska-resenja-konacno.pdf?script=lat (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- Prostorni plan opštine Vrnjačka Banja [Spatial Plan of the Municipality of Vrnjacka Banja]. 2011. Available online: https://vrnjcispa.biz/baze-i-registri/vazeci-planovi/prostorni-plan-opstine-vrnjacka-banja (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Uredba o utvrđivanju područja Banje [Government Order Establishing the Area of the Vrnjačka Banja Spa]. 1997. Available online: http://www.pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/SlGlasnikPortal/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/uredba/1997/26/2/reg (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Prostorni plan opštine Bor [Spatial Plan of the Municipality of Bor]. 2014. Available online: http://bor.rs/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/PPO-Bor-Knjiga-1_januar-2014.pdf?script=lat (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- Generalni urbanistički plan Bora [General Urban Plan of Bor]. 2015. Available online: http://bor.rs/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Knjiga-I_Plan.pdf?script=lat (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- Odluka o građevinskom zemljištu [Decision on Development Land]. Službeni list opštine Bor, br. 3/1983.

- Odluka o javnom građevinskom zemljištu [Decision on Public Development Land]. Službeni list opštine Bor, br. 2/2016.

| Territorial Organisation | Institutions | Laws | Standards of Protection |

|---|---|---|---|

| National level | Government of Serbia | Government Order on the Environmental Network [70] Government Order on Safeguards [71] | Environmentally significant areas Area safeguards |

| Ministry of Construction, Transportation and Infrastructure | Law on the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia [72] | Land use balance at the national level | |

| Planning and Construction Law [67] | Change in intended use of forest land to development land | ||

| Expropriation Law [73] | Determination of land of public interest | ||

| Public Property Law [74] | Resources of general interest (national level) | ||

| Resources in general use (local level) | |||

| Right to use public property | |||

| Utilities Law [75] | Management and maintenance of public green surfaces | ||

| Ministry of Environmental Protection | Nature Conservation Law [76] | Natural resources and natural values | |

| Protected areas | |||

| Environmental Protection Law [77] | Forest development plans and forest management rules | ||

| Safeguards and options for use as defined by plans | |||

| Forests Law [66] | Ban on sale of publicly-owned forests | ||

| Prohibited activities | |||

| Conditions for change in intended use | |||

| Environmental Impact Assessment Law [78] | Preventive protection measures | ||

| Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment Law [79] | Preventive protection measures | ||

| Serbian Nature Conservation Institute | Safeguards and conditions for their implementation | ||

| Regional level* | Vojvodina Urban Planning Institute | Vojvodina Regional Spatial Plan | |

| Vojvodina Nature Conservation Institute | Protection programmes Safeguards and conditions for their implementation | ||

| Special-purpose areas (no administrative powers) | Spatial plans for special purpose areas | ||

| Local level | Local authorities’ departments | Local authority spatial plan | Land use balance at the local level |

| General Urban Plan | Land use Zoning Building codes | ||

| General Zoning Plan | |||

| Detailed Zoning Plan | |||

| State-owned enterprises tasked with developing natural resources | Development and maintenance programmes |

| Policy Document | Values: Urban Forest |

|---|---|

| National Sustainable Development Strategy [82] | Sets out strategic objectives for management and use of forests and forest land, mandates an institutional framework for safeguarding the protective functions of forests, and provides a model for inter-sectoral cooperation in the development of plans. |

| National Strategy for Sustainable Use of Natural Resources [81] | Defines the concept of ‘forests’ and ‘forest land’; highlights the significance of forests as finite biological resources used, amongst other purposes, for sports, recreation and tourism; and cites the overexpansion of tourism capacity and infrastructure as a threat. Lays out the ultimate objective of sustainable development—balance between the use of all forest functions to ensure lasting multifunctionality in the provision of material goods and other ecosystem services. Advocates the introduction of institutional and economic measures to preserve and advance the recreational and health-related functions of forests and forest ecosystems. Envisages the creation of 5000 hectares of new town and suburban forests (by 2020). |

| Forestry Development Strategy [83] | Introduces the fundamental objective of safeguarding and enhancing forests and developing forestry as an industry. Particularly advocates the preservation, advancement, sustainable use, and acknowledgment of the protective, social, cultural and regulatory functions of forests and reform and advancement of institutions in the forestry sector. |

| Biodiversity Strategy, 2011–2018 [84] | Provides an overview of the state of biodiversity, safeguards and the legal, institutional and financial framework for preserving biodiversity; defines strategic areas, goals and activities and includes an action plan. Divides forests by how mixed they are and provides recommendations to achieve the objectives of reducing loss of habitat, including forests, by 2020, and instituting protection of 17% of all land and water areas subject to safeguards. The strategy sets out a framework for measures to prevent adverse impacts of genetically modified species of trees and allochthonous and invasive species on forests and biodiversity. Also advocates development of forest certification programmes and best sustainable forestry practices based on an ecosystem-wide approach. |

| National Environmental Protection Programme [85] | Advocates the preservation, improvement and extension of existing forests and enhanced monitoring in line with international frameworks. |

| Law Ratifying the Convention on Biological Diversity [86]* | Advocates the preservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and all its components. Requires biodiversity issues to be considered when any national decisions are being made to preserve and sustainably use biological resources and measures to be adopted to avoid and minimise adverse impacts on biodiversity. |

| Law Ratifying the European Landscape Convention [57]* | Sets out the principles that each country should adjust to suit its national law and incorporate into spatial development policies. The Convention defines ‘landscape’ as a dynamic category that comprises areas of action of both natural and human resources, and advocates dialogue in enacting landscape development policies, especially at the local level to facilitate practical implementation. |

| Law Ratifying the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters [60]* | This convention, also referred to as the Aarhus Convention, guarantees the right to access information, participate in decision-making, and access justice in environmental matters. It establishes principles that public administration should adhere to when communicating with the public on environmental issues so as to safeguard the right of everyone, whether belonging to present or future generations, to live in an environment adequate to his or her health and well-being. |

| General Zoning Plan | Vrnjačka Banja |

|---|---|

| Area covered | 2.318,97 hectares |

| Existing use | Forests (public use) |

| Planned use | Forest park |

| Area/percentage of total area covered by plan | 150,3 hectares/6.5% |

| Objective of change of use to forest park | Forest configurations entailing additional attention in terms of maintenance, care and protection with a minimum of park facilities. The primary objective is to maximise the protection of forests and greenery in general, safeguard autochthonous vegetation, landscape configurations, and characters of areas. These zones most commonly integrate recreational and tourism-related facilities of central and boundary areas. These areas are designed for tourism and/or meeting the needs of the residential population of all ages. |

| Development rules | Construction of appropriate hydraulic engineering structures to provide protection from torrential flooding and floods; Provision of discreet lighting and street furniture as designed; Scheduled maintenance as part of park care projects; Provision of cafe and restaurant facilities (construction of 1 to 3 buildings of up to 150 square metres) |

| Restrictions | Change in intended use of space, construction of structures, tree felling and unplanned removal of vegetation, earth moving works, vehicle movements, waste disposal |

| Implementation conditions/instruments | Urban Planning Design required. General Zoning Plan required for Forest Park 1 (10,46 ha), Forest Park 2 (17,31 ha) and Forest Park 3 (34,91 ha) |

| Protection zones | Sanitary Protection Zone 2 |

| Protection conditions | Greenery of major importance for the character of the area (Borjak) Conditions issued by the Kraljevo Cultural Heritage Institute (Forest Park 1 as whole) |

| General Zoning Plan | Town of Bor |

|---|---|

| Area covered | 1312,20 ha |

| Existing use | Urban greenery (public use) |

| Planned use | Forest park |

| Area/percentage of total area covered by plan | 11,2 ha/0.85% |

| Objective of change of use to forest park | Conversion of a forest, including a zoo, into a forest park. Development of recreation and tourism facilities |

| Development rules | Basic natural characteristics to be retained Minimum development:

Only natural materials to be used for all paths, minimum lighting Only natural materials (wood and stone) to be used for benches and rest areas Parking spaces to be sited at the main approaches to the forest Endeavour to restrict movement to pedestrians only Provide signage and development and maintenance programmes |

| Restrictions | - |

| Implementation conditions/instruments | Appropriate technical documentation must be developed for newly planned green areas and reconstruction of existing ones. The Plan repealed the Zoning Plan for ‘Section 3’—Forest Park (Municipal Official Journal Nos. 19/94, 4/01 и 14/03). |

| Protection zones | - |

| Protection conditions | - |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maruna, M.; Crnčević, T.; Milojević, M.P. The Institutional Structure of Land Use Planning for Urban Forest Protection in the Post-Socialist Transition Environment: Serbian Experiences. Forests 2019, 10, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10070560

Maruna M, Crnčević T, Milojević MP. The Institutional Structure of Land Use Planning for Urban Forest Protection in the Post-Socialist Transition Environment: Serbian Experiences. Forests. 2019; 10(7):560. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10070560

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaruna, Marija, Tijana Crnčević, and Milica P. Milojević. 2019. "The Institutional Structure of Land Use Planning for Urban Forest Protection in the Post-Socialist Transition Environment: Serbian Experiences" Forests 10, no. 7: 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10070560

APA StyleMaruna, M., Crnčević, T., & Milojević, M. P. (2019). The Institutional Structure of Land Use Planning for Urban Forest Protection in the Post-Socialist Transition Environment: Serbian Experiences. Forests, 10(7), 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10070560