Abstract

Research Highlights: The majority of non-conformities (NCs) occurred under environmental impact (Principle 6) in all regions, and contributed on average to 40% and 48% of the total number of minor and major NCs respectively. Background and Objectives: The performance of certified companies operating has been frequently criticized in Russia. The aim of this study was to analyse the NCs of FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) -certified companies in northwestern (NW) Russia during the period 2011–2015. Materials and Methods: In total, 69 FSC certificates were assessed, representing 112 FSC-certified companies. It should be noted that the number of certificates in this study increased 2.4-fold (from 29 to 69) during the period 2011–2015. At the same time, the number of minor NCs increased only 1.6-fold (from 221 in 2011 to 363 in 2015), while the number of major NCs increased 3.4-fold (from 25 in 2011 to 84 in 2015). Results: During the five-year period, the highest number of NCs was issued in the Arkhangelsk region and in Republic of Karelia, followed by the Vologda region. On the contrary highest number of issued NCs both minor and major per 1000 ha of certified area was in the Novgorod region. The data were also analyzed on leaseholder level and preliminary split into three categories. Conclusions: The number of NCs was, on average, higher for large-sized leaseholders for both the major and minor NCs in comparison to medium- and small-sized leaseholders. However, there were no significant statistical differences observed.

1. Introduction

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification emerged in the 1990s as a tool to facilitate the sustainable use of forest resources [1]. It is a voluntary instrument, regarded as a market-driven mechanism to provide incentives for responsible forest management [2,3,4,5]. The emergence of FSC certification in Russia was initiated by environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) in the late 1990s [6]. The Kosihinskiy leskhoz (State forestry management unit) from the Altay region was the first company to receive FSC forest management (FM) certification in 2000 [7]. As of 1 March 2019, 43 million ha of forests have been certified according to the FSC scheme, with 796 chain-of-custody (COC) certificates and 235 FM/COC certificates [8].

Although the progress of FSC certification has been rapid, FM certificates covered only 27% of all the leased forest area in Russia in 2016 [9]. Nevertheless, the development of national principles for sustainable forest management (SFM) had commenced by 1999 and resulted in the adoption of the Russian National Standard—a key document that describes SFM practices on an indicator level tailored to Russian conditions. The sustainability principles and criteria are similar to the generic FSC version and have been adopted by the Russian FSC Accreditation Committee [10]. The current version of the Russian National FSC (6.1 FSC-STD-RUS-V6-1-201) has been in use since 2013 [11].

The Russian National FSC Forest Management Standard consists of 10 Principles and 56 criteria; the detailed split down to indicator level is presented in Table 1 [11].

Table 1.

Structure of Russian National Forest Management Standard.

The development of forest certification was highly supported by liberalization and decentralization of the forest management system over the last 10 years in Russia. It was reflected in the main forestry legislation [12], which was adopted in 2006 and was enforced in January 2007. Decentralization has resulted in a shift in tenure rights from the state forest management units to private forest leaseholders and an extension of leasing rights from 10 to 49 years [13]. Forest leaseholders are the ones who certify their forest concessions; in exceptional cases non-leased forest areas are certified. Moreover, Russia joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), which has made trading rules and tax quotas more transparent [14]. According to Teplyakov et al. [15] and Pappila [16], poor enforcement of recently introduced state regulation has not tackled the problem of illegal loggings. Many experts believe that a voluntary forest certification scheme (e.g., FSC) may improve the governance in general, and decrease the level of illegal logging in Russia [17,18,19,20,21,22]. In addition, it has been argued that safeguarding the remaining intact forest landscapes as a category of high-conservation value forests would succeed if the Motion 65 initiative is enforced by FSC International from January 2017 [23].

The verification of compliance is made on annual basis by an accredited independent third-party, the certification body (CB), which ensures credibility of the certification scheme [24,25]. The CB must ensure that no activity affects the confidentiality and objectivity of the certification process. Moreover, the CB is responsible for the liability of its decisions, and has to be impartial when issuing, withdrawing, or suspending the certificate [26]. The auditing team (auditors) has an essential role in the certification process, acting on behalf of the CB. Auditors are responsible for the collection of information, analyses, and processing, in order to verify the degree or severity to which each indicator of the FSC standard is fulfilled or not [27].

The degree of non-conformities (NCs) can be either minor, i.e., non-systematic, having a limited impact in time and space, or major, i.e., systematic and compromising an FSC principle as a credible scheme. In addition, the auditing team may provide recommendations (observations) to the certificate holder or potential candidate related to forest management, with the main aim of avoiding further deviations from the FSC standard requirements [28]. The life cycle of an FSC certificate is a five-year period and starts with pre-assessment (optional), followed by the main assessment and annual audits, and finally a re-certification at the end of the fifth year [29]. In the assessment report, the audit team is required to document all identified NCs and determine their severity, grading from minor to major non-conformity. The assessment of NCs is followed by requests for a corrective action report that aims to eliminate the NCs.

NCs can be graded by auditors as either major or minor. The major NCs imply prohibition: they have to be solved before the certificate will be granted. Minor NCs do not prevent from obtaining the certificate. These NCs have to be resolved within one year in the corrective action report (CAR). Minor NCs that are not resolved after one year automatically become major ones in the following annual audit and then have to be solved in three months. There are no quantitative limits to the number of minor NCs. However, if too many minor NCs are found for the same criterion, the criterion itself might be tagged as a major NC.

The auditing and decision-making process has a two-level system, which ensures that the auditing team cannot make the final decision on the issuing of the certification. The auditing team submits the report (with their own suggestion upon decision) to an independent observer with the technical knowledge required to assess the report [28]. As such, the decision on certification is not taken by the auditing team, but by the CB, who takes into consideration the evaluation made by the auditing team and the comments made by the independent observer. This person is an external expert and is independent of the CB. This overall procedure exists in order to minimize any influence on the final decision of issued certificates.

Scientific research related to the FSC certification has increased during recent years [30,31]. Numerous articles have been published on the development of forest certification, both globally [2,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] and in Russia [6,17,20,21,31,42,43]. However, research related to the analysis of performance gaps of certified companies is needed in Russia to understand the root cause and understand where the failures take place.

Despite the rapid development of FSC certification, Greenpeace of Russia brought attention to the fact that fulfillment of Principle 9 often fails. Moreover, the absence of aggregated data makes it difficult to relate minor or major failure to the principles. Therefore, the aim of the study was to analyse the NCs of the FSC-certified companies in NW Russia during the period 2011–2015 against the standard, and to identify on principle level the minor and major NCs and identify the regions with the most failures.

2. Materials and Methods

The study area covered all nine regions of northwestern federal district (FD) of Russia (i.e., Karelia, Komi, Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Leningrad, Novgorod, Murmansk, Pskov, and Kaliningrad). Information regarding NCs was obtained from public reports related to forest management (FM) practices, which were available in Russian and English on the FSC web-page (www.info.fsc.org). Identified NCs were recorded in a Microsoft Excel file and were allocated in accordance to one of the ten FSC Principles [44] based on severity (minor or major). In addition, the database included information on certified area and type of certificate. As of July 2016, FM certificates were only recorded in six (Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Karelia, Komi, Leningrad, and Novgorod) out of the nine regions. All the active certificates (as of 18 July 2016) from the NW Russia were used in the analysis.

Collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). A Kruskal–Wallis test was chosen based on references from other quantitative studies analyzing statistical significance among FSC certificates within forest leases of different sizes and was done separately for the major and minor NCs. For that purpose, the data were re-coded according to the size of leased forest area, where 1 = 0–100,000 ha (small size), 2 = 100,001–300,000 ha (medium size), 3 = over 300,001 ha (large size). The intervals for leased forest areas were chosen based on consultation with the FSC auditors from CB, and are typically used by them in Russian Federation. Thus, the split was based on the practical experience of the Russian forestry experts. The number of NCs was also re-coded for statistical analysis. Thus, for minor NCs: 1 = 1–5 NCs, 2 = 6–10 NCs, 3 = over 10 NCs; whereas for major NCs: 1 = 1–3 NCs, 2 = 4–6 NCs, 3 = over 6 NCs.

Moreover, the performance level of certified companies on regional level was identified for the reference year 2015. The total frequency of NCs was calculated per 1000 ha of certified area in order to make numbers comparable.

The chosen period for assessment of NCs (i.e., during the period 2011 to 2015) was also the transition period for the shift from version 6.0 to 6.1 of the Russian National Standard. Thus, companies were assessed against version 6.0 prior to 2013, and against version 6.1 after 2013.

3. Results

The distribution of FSC FM certificates during the period 2011–2015 is presented in Table 2. About 84% of all certificates were from individuals (i.e., certification for one member (company) under a single FSC certificate); group certification is designed to help reduce the costs of certification—the cost per group member is significantly lower than if each member applied for an individual certificate [45]. The total number of FSC certificates during the five-year period increased more than two-fold, from 29 to 69 certificates.

Table 2.

Distribution of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certificates among the regions of northwestern (NW) Russia.

Over 20 million hectares of forest in NW Russia are FSC-certified (Table 2), which represents 16% of the total forest area in this region [46]. Over 40% of all the certified forests were in Arkhangelsk region, followed by Karelia (19%). The least certified forests were in the Novgorod region, accounting for only 1% of the total certified area in NW Russia. The range of FM certificates varied from 5000 to 1.5 million hectares (Table 3).

Table 3.

Certified area by the region and range of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certificates.

The majority of minor NCs occurred under Principle 6 (Table 4), which contributed, on average, to 40% of all the minor NCs recorded, followed by Principles 4 (14%), 8 (12%), 5 (10%), and 9 (9%). Throughout the 2011–2015 period, the number of certificates issued increased 2.3-fold, while the number of minor NCs increased 1.6-fold. Since none of the NCs were issued in Principle 10 it was considered redundant and was taken away for further analysis.

Table 4.

Frequencies of minor non-conformities (NCs) in NW Russia for 2011–2015.

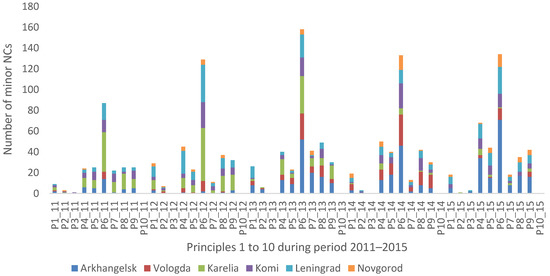

The majority of minor NCs occurred in the Republic of Karelia in 2011 (38%) and 2012 (51%) within Principle 6 (Figure 1). In 2013–2015, the majority of NCs occurred in the Arkhangelsk region within Principle 6; 52% (2013), 46% (2014), and 71% (2015).

Figure 1.

Distribution of minor non-conformities (NCs) among the regions in the period 2011–2015.

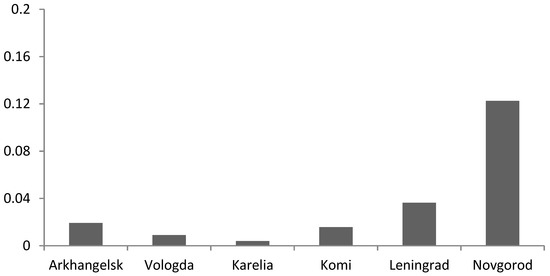

As can be seen from Figure 2, the highest number of minor NCs per 1000 hectares of certified area was in the Novgorod region (0.12)—significantly higher than in the Leningrad (0.04) and Arkhangelsk (0.02) regions. The lowest number of minor NCs was in the Republic of Karelia (0.004).

Figure 2.

Total number of minor NCs per 1000 ha of certified forests among regions in 2015.

Most minor NCs (37%) occurred within Principle 6 (Table 5). The total number of issued NCs was highest for large-sized leaseholders (56), followed by small- (41) and medium-sized leaseholders (37). Within Principles 4 and 5, the large-sized leaseholders had more NCs than the small- and medium-sized leaseholders, whereas within Principles 8 and 9, more NCs were found among the small-sized leaseholders. Moreover, statistically significant differences in the occurrence of minor NCs were not found between three groups of leaseholders.

Table 5.

The distribution of minor non-conformities (NCs) according to the size of leased forest area in 2015 (n = 69).

The majority of major NCs occurred within Principle 6 (Table 6), which contributed, on average, to about half of all major NCs. Average major NCs were 6%, 8%, 11%, and 18% within Principles 5, 8, 9, and 4, respectively (Table 6). The number of certificates increased 2.3-fold throughout the study period when the number of major NCs increased 3.4-fold. Since none of the NCs were issued in Principle 10 it was considered redundant and was taken away for further analysis.

Table 6.

Frequency of major non-conformities (NCs) in NW Russia 2011–2015.

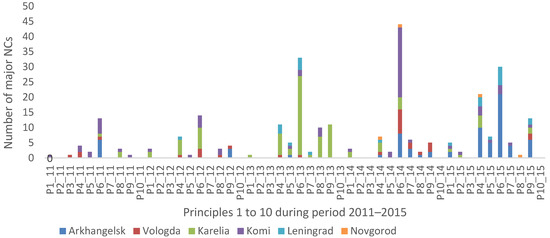

The majority of major NCs (six) occurred in the Arkhangelsk region within Principle 6 in 2011 (Figure 3). In 2012 and 2013, the majority of major NCs occurred in the Republic of Karelia within Principle 6 (7 and 26 frequencies, respectively). In 2014 and 2015, most of the major NCs were issued in the Vologda (23) and Arkhangelsk (21) regions.

Figure 3.

Distribution of major non-conformities (NCs) among the regions during 2011–2015.

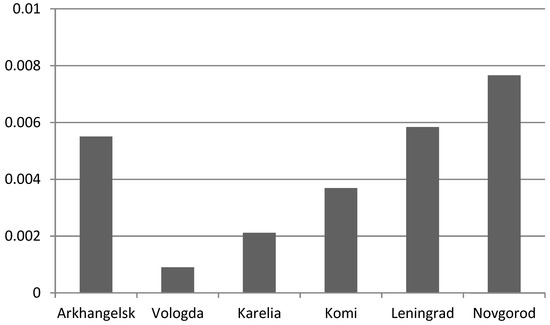

As can be seen from Figure 4, the highest number of major NCs per 1000 hectares of certified area was in the Novgorod region (0.008)—significantly higher than in Leningrad (0.006) and Arkhangelsk (0.006) regions. The lowest number of major NCs was in the Vologda region (0.0009).

Figure 4.

Total number of major NCs per 1000 ha of certified forests among regions in 2015.

Most of the major NCs occurred within Principle 6 (30%) for the small- and large-sized leaseholders (Table 7). Most of the major NCs for middle-sized leaseholders occurred within Principle 5 (31%). The total number of major NCs was higher in the large-sized leaseholders group. Within Principles 4 and 9, small-sized leaseholders had more major NCs (27% and 23%) compared to the large- (24% and 16%) and medium-sized leaseholders (23% and 0%). Within Principle 7, more major NCs occurred in the medium-sized leaseholders group (23%). However, no statistically significant differences were found between the three groups.

Table 7.

The distribution of major non-conformities (NCs) according to the size of leased forest area in 2015 (n = 69).

A high number of major and minor NCs were found in the Arkhangelsk, Karelia, and Vologda regions (Table 8), whereas the majority of certificates were issued in the Arkhangelsk (33%), Leningrad (19%), and Vologda (16%) regions, followed by Karelia (13%), Komi (12%), and Novgorod (7%). In our opinion, this might be associated with the fact that the proportion of certificates issued by Nepcon in the regions, e.g., Karelia (100%) and Arkhangelsk (87%), were significantly higher compared to other regions (Table 8). Nepcon is a non-profit organization [47], and in actuality may be more demanding that leaseholders meet the standards criteria than other certification bodies in Russia that represent consulting companies and other types of profit-making companies.

Table 8.

Certificates issued by certification bodies.

4. Discussion

A significantly higher number of both minor and major NCs was found in the Novgorod region compared to other regions of the NW Federal district. A key explanation for this might be regional variations (i.e., development of processing industry within the region and their internationalization status), number of issued certificates, average size of the company’s leases, and the nature of certification bodies, and others. More detailed qualitative analysis in the region is needed to identify the root cause for this.

Among the three groups of leaseholders, the total number of NCs was higher for large-sized leaseholders, both for major and minor NCs. However, this result partly contradicts the earlier findings of Trishkin et al. [20]. In their study, the survey was conducted among certified and non-certified companies, but the majority of non-certified companies represented small-scale companies, and certified ones represented medium and large enterprise companies. However, in the current study the large-sized leaseholders had the most NCs in both categories. On one hand, they are more financially viable and can mobilize human resources for additional work if required to fulfill the certification requirements; on the other, large-sized leaseholders might choose more strict and demanding CBs, which leads to more NCs issued during annual assessments. The analysis of non-conformities corresponds to 112 FSC-certified companies or 69 FSC FM/COC certificates covering six regions of NW Russia. It revealed that the majority of NCs occurred in Principle 6 (environmental impact)—40% and 48% for minor and major NCs, respectively. The requirements of this principle are not reflected in Russian forestry legislation (e.g., Forest Code). Therefore, leaseholders quite often do not have internal capacities to fulfill its requirements and have to seek external assistance and consultancy for how to comply with that. However, the integration of good practices related to environmental impact into daily operation and internal training and/or control appears to be the key bottleneck. Our findings are in line with earlier findings by Hain [48] in Estonia and Halalisan et al. [49] in five countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Estonia, Romania, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom), who also reported that most NCs occurred in Principle 6. Thus, the results of this study are in agreement with previous research in other countries. Additionally, Principle 6 of Russian National FSC Standard contains the highest number of indicators compared to other principles (Table 1); therefore, a high number of NCs can be explained by complexity and higher performance level by leaseholder.

It is worth mentioning that an earlier published research article related to development of forest certification in Russia also concluded that the majority of NCs were issues with Principle 6 [50]. This is again in line with the findings of this study. However, the authors there simplified the approach and did not split NCs into minor and major and considered them together in the analysis.

The main limitation of this study was that NCs were analysed for the FSC certification scheme only. The Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) is another global certification scheme which is currently developing fast in Russia. However, due to the dominance of FSC and the longer history of its presence in the country it was decided to focus only on the analysis of FSC certificates. Moreover, analysis in this study was done on Principle level (i.e., simplification of the results), and if the analysis was be made on criterion/indicator level it could bring more additional value and shift the analysis from more descriptive and quantitative into more qualitative-oriented with a more individual approach and possibilities to make the root cause analysis for identified gaps. In addition, the absence of statistics for suspended certificates in the analysis part made it less versatile and elaborative.

The methodology applied in this article is considered to be appropriate, as we achieved the main aims set up in the end of the introduction section and it is possible to repeat the analysis following our guidelines in the methodology.

There are numerous publications related to forest certification on a global scale during the last two decades when the certification process started to develop actively in many parts of the world [2,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], including research in Russia [6,17,20,21,31,42,43]. However, only a few studies from different parts of the world have attempted to analyse the performance level related to forest management based on issued NCs [48,49,50,51,52]. At the same, there is a general need for further research related to the performance of certified companies and NCs issued by different CBs in other federal regions of Russia and comprehensive comparison among the federal districts within the country. Thus, a clear understanding of short and long-term dynamics for minor and major failures by the leaseholders will lead to more comprehensive follow up together with the CBs and other stakeholders. The development of forest certification (e.g., driven by FSC) in the country has received more attention lately, domestically and internationally, due to the high level of internationalization of wood markets and product placement. The impact of the study is significant, as the NW Russia accounts for more than 50% of all FSC FM/COC certificates issued in the country. Therefore, the findings of this study can be projected for the entire country, and can be widely utilized for scientific and other purposes, such as increasing awareness among specialists and the general public towards forest certification.

5. Conclusions

The development of FSC certification in NW Russia has been steadily increasing, however unevenly among the study regions, and at the same time the share of certified forests is the highest in NW Russia compared to other federal districts. The performance of FSC certified companies in the region is likely to improve in coming years if the majority of the same companies will continue to be FSC certified, as they will get more experience related to performance. Wider stakeholder involvement prior the assessment and assistance from third party consultants might have a positive influence on the performance level of the companies and consequently may lead to a lower number of non-conformities. Additionally, the introduction of different management standards (e.g., ISO 14001: Environmental Management) and others may improve the performance, as they require a systematic approach, which includes constant follow-up measures and self-control.

An understanding of typical minor and major failures tailored to Principle level is an important starting point to take adequate measures for the leaseholders in the most cost-effective way. Like in many other countries, direct and indirect costs related to the assessment and wider inclusion of local communities, NGOs, and local and regional authorities remain challenging.

Author Contributions

M.T. is fully responsible for the article starting from preparation and writing all the sections. T.K. and J.K. provided revision and editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to School of Forest Sciences, University of Eastern Finland. M.T. is thankful to anonymous reviewer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cubbage, F.; Harou, P.; Sills, E. Policy instruments to enhance multi-functional forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Auld, G.; Newsom, D. Forest certification (eco-labeling) programs and their policy-making authority: Explaining divergence among North American and European case studies. For. Policy Econ. 2002, 5, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullison, R.E. Does certification conserve biodiversity? Oryx 2003, 37, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karna, J.; Hansen, E.; Juslin, H. Environmental activity and forest certification in marketing of forest products: A case study in Europe. Silva Fenn. 2003, 37, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Auld, G.; Newsom, D. Governing through Markets: Forest Certification and the Emergence of Non-State Authority; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2004; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Tysiachniouk, M. Transnational environmental NGOs as actors of ecological modernization in Russian forest sector. In Ecological Modernization of Forest Sector in Russia and the United States; Tysiachniouk, M., Kulyasov, I., Pchelkina, S., Eds.; Research Chemistry Center of Saint-Petersburg State University: Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 2003; pp. 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Russian Forest Portal. Sertifikat No. 1 vedeniya ustoichivogo lesnogo chozjaistva na Altae. [First FSC Certificate of Sustainable Forest Management Practices in Altay Region]. Available online: http://www.forest.ru/rus/sustainable_forestry/certification/woodmark.html (accessed on 3 September 2018). (In Russian).

- FSC Russia. Facts and Figures 2019 (Valid as of 1st March 2019). Available online: https://ru.fsc.org/ru-ru (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Ministry of Natural Resource of Russian Federation. State of Russian Forests. Available online: http://www.mnr.gov.ru/regulatory/detail.php?ID=254471 (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Karpachevskiy, M.; Chuprov, V.; Ptichnikov, A. Rossiyskiy nacionalniy standart Lesnogo Popechitelskogo Soveta [Russian national standard of Forest Stewardship Council]. Ustoichivoe Lesopolzovanie 2009, 1, 10–12. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- FSC Russia. Russia National Standard FSC (FSC-STD-RUS-06-01-2012). Available online: https://ic.fsc.org/en/certification/national-standards/europe-russia/russia (accessed on 19 November 2018).

- Forest Code of the Russian Federation. No. 200-FZ. Available online: http://faolex.fao.org (accessed on 16 April 2018).

- Torniainen, T. Institutions and Forest Tenure in the Russian Forest Policy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- International Forest Industries (IFI). Russia Finally Joins WTO. 2012. Available online: http://www.internationalforestindustries.com/2012/01/12/russia-finally-joins-wto (accessed on 6 September 2018).

- Teplyakov, V.; Grigoriev, A. Forest Governance and Illegal Logging: Improving legislation, and Interagency and Inter-Stakeholder Relations in Russia; IUCN, Office for the Commonwealth of Independent States: Moscow, Russia, 2006; ISBN 5-87317-268-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pappila, M. Forest certification and trust—Different roles in different environments. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 31, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysiachniouk, M. Forest certification in Russia. In Confronting Sustainability: Forest Certification in Developing and Transitioning Countries; Cashore, B., Gale, F., Meidinger, E., Newsom, D., Eds.; Publication Series; Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies: Yale, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 261–295. [Google Scholar]

- WWF Russia. Systemy Otslezhivaniya Proishozhdeniya Drevesiny v Rossiyskoy Federatsii: Opyt Lesopromyshlennyh Kompaniy I Organov Upravleniya Lesami. [Tracing of Wood Origin in the Russian Federation: Experience of Forest Industry Companies and Forest Management Bodies]; WWF Russia: Moscow, Russia, 2011. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ptichnikov, A.V.; Bubko, E.V.; Zagidullina, A.T. Dobrovolnaya Lesnaya Sertifikaciya [Voluntary Forest Certification]; WWF Russia: Moscow, Russia, 2011. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Trishkin, M.; Lopatin, E.; Karjalainen, T. Assessment of motivation and attitudes of forest industry companies toward forest certification in northwestern Russia. Scand. J. For. Res. 2014, 29, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trishkin, M.; Lopatin, E.; Karjalainen, T. Exploratory Assessment of a Company’s Due Diligence System against the EU Timber Regulation: A Case Study from Northwestern Russia. Forests 2015, 6, 1380–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trishkin, M.; Lopatin, E.; Shmatkov, N.; Karjalainen, T. Assessment of sustainability of forest management practices on the operational level in northwestern Russia—A case study from the Republic of Karelia. Scand. J. For. Res. 2017, 32, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestforum of Greanpeace Russia. The Joint Position of Greenpeace Russia and WWF Russia on Voluntary Forest Certification Schemes. Available online: http://www.forestforum.ru/viewtopic.php?f=28&t=20495 (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Accreditation Services International. FSC Accreditation Process. Available online: http://www.accreditation-services.com/programs/fsc (accessed on 6 October 2018).

- FSC International. General Accreditation Standard. (FSC-STD-20-001). Available online: https://ic.fsc.org/en/certification/processes-and-reviews/archived-processes/fsc-std-20-001 (accessed on 3 November 2018).

- ISO/IEC 65 Guide. General Requirements for Certification Bodies. Available online: http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=26796 (accessed on 17 January 2019).

- Nussbaum, R.; Jennings, S.; Garforth, M. Assessing Forest Certification Schemes: A Practical Guide; Proforest: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- FSC International. FSC-STD-20-007 Standard: Forest Management Evaluations. Available online: https://ic.fsc.org/preview.fsc-std-20-007-v3-0-en-forestmanagement-evaluations.a-524.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2019).

- FSC International. FSC User-Friendly Guide to FSC Certifcation for Smallholders. Available online: https://ic.fsc.org/en/smallholders/certification-01/steps-to-certification (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumreoder, J.S.; Hobson, P.R.; Graebener, U.F.; Kruger, J.-A.; Dobrynin, D.; Burova, N.; Amosa, I.; Winter, S.; Ibisch, P.L. Towards the evaluation of the ecological effectiveness of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC): Case study in the Arkhangelsk Region in the Russian Federation. Chall. Sustain. 2018, 6, 20–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kallas, A. Public forest policy making in post-Communist Estonia. For. Policy Econ. 2002, 4, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Van Kooten, G.C.; Vertinsky, I.; Auld, G.; Affolderback, J. Private or self-regulation? A comparative study of forest certification choices in Canada, the United States and Germany. For. Policy Econ. 2003, 7, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozinga, S. Footprints in the Forest-Current Practice and Future Challenges in Forest Certification; Forests and the European Union Resource Network (FERN): Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nebel, G.; Quevedo, L.; Jacobsen, J.B.; Helles, F. Development and economic significance of forest certification: The case of FSC in Bolivia. For. Policy Econ. 2005, 7, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsom, D.; Bahm, V.; Cashore, B. Does forest certification matter? An analysis of operation-level changes required during the SmartWood certification process in the United States. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 9, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdevest, C.; Rickenbach, M.G. Forest certification and institutional governance: An empirical study of forest stewardship council certificate holders in the United States. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 9, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, M.; Kant, S.; Couto, L. Why Brazilian companies are certifying their forests? For. Policy Econ. 2008, 11, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubbage, F.; Diaz, D.; Yapura, P.; Dube, F. Impacts of forest management certification in Argentina and Chile. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.H.; Allen, P. Beyond organic and fair trade? An analysis of ecolabel preferences in the United States. Rural Sociol. 2010, 75, 244–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, M.; Tikina, A.; Larson, B. Forest certification audit results as potential changes in forest management in Canada. For. Chron. 2010, 86, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskitalo, E.C.H.; Sandström, C.; Tysiachniouk, M.; Johansson, J. Local consequences of applying international norms: Differences in the application of forest certification in Northern Sweden, Northern Finland, and Northwest Russia. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, Art-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.A.; Tysiachniouk, M. The uneven response to global environmental governance: Russia’s contentious politics of forest certification. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 90, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSC International. FSC Principles and Criteria. Available online: https://ic.fsc.org/en/certification/principles-and-criteria (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- FSC International. Group Certification. Available online: https://us.fsc.org/en-us/certification/group-certification (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Karjalainen, T.; Leinonen, T.; Gerasimov, Y.; Husso, M.; Karvinen, S. Intensification of Forest Management and Improvement of Wood Harvesting in Northwest Russia—Final Report of the Research Project; Finnish Forest Research Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nepcon. About Us. Available online: http://www.nepcon.org/about-us (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Hain, H. The Role of Voluntary Certification in Promoting Sustainable Natural Resource Use in Transitional Economies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Halalisan, A.F.; Ioras, F.; Korjus, H.; Avdibegovic, M.; Maric, B.; Malovrh, S.P.; Abrudan, I.V. An Analysis of Forest Management Non-Conformities to FSC Standards in Different European Countries. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2016, 44, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashevich, V.; Shegelman, I.; Vasilyev, A.; Lukashevich, M. Forest certification in Russia: Develoment, current state and problems. Lesicky Cas. For. J. 2016, 62, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rafael, G.C.; Fonseca, A.; Gonçalves Jacovine, L.A. Non conformities to the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) standards: Empirical evidence and implications for policy making in Brazil. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 88, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Sills, E.O.; Guariguata, M.R.; Cerutti, P.O.; Lescuyer, G.; Putz, F.E. Evaluation of the impacts of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification of natural forest management in the tropics: A rigorous approach to assessment of a complex conservation intervention. Int. For. Rev. 2017, 19, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).