Effects of Changing Temperature on Gross N Transformation Rates in Acidic Subtropical Forest Soils

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Sampling

2.2. 15N tracing Experiment

2.3. Analysis of Soil Properties

2.4. Calculations and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

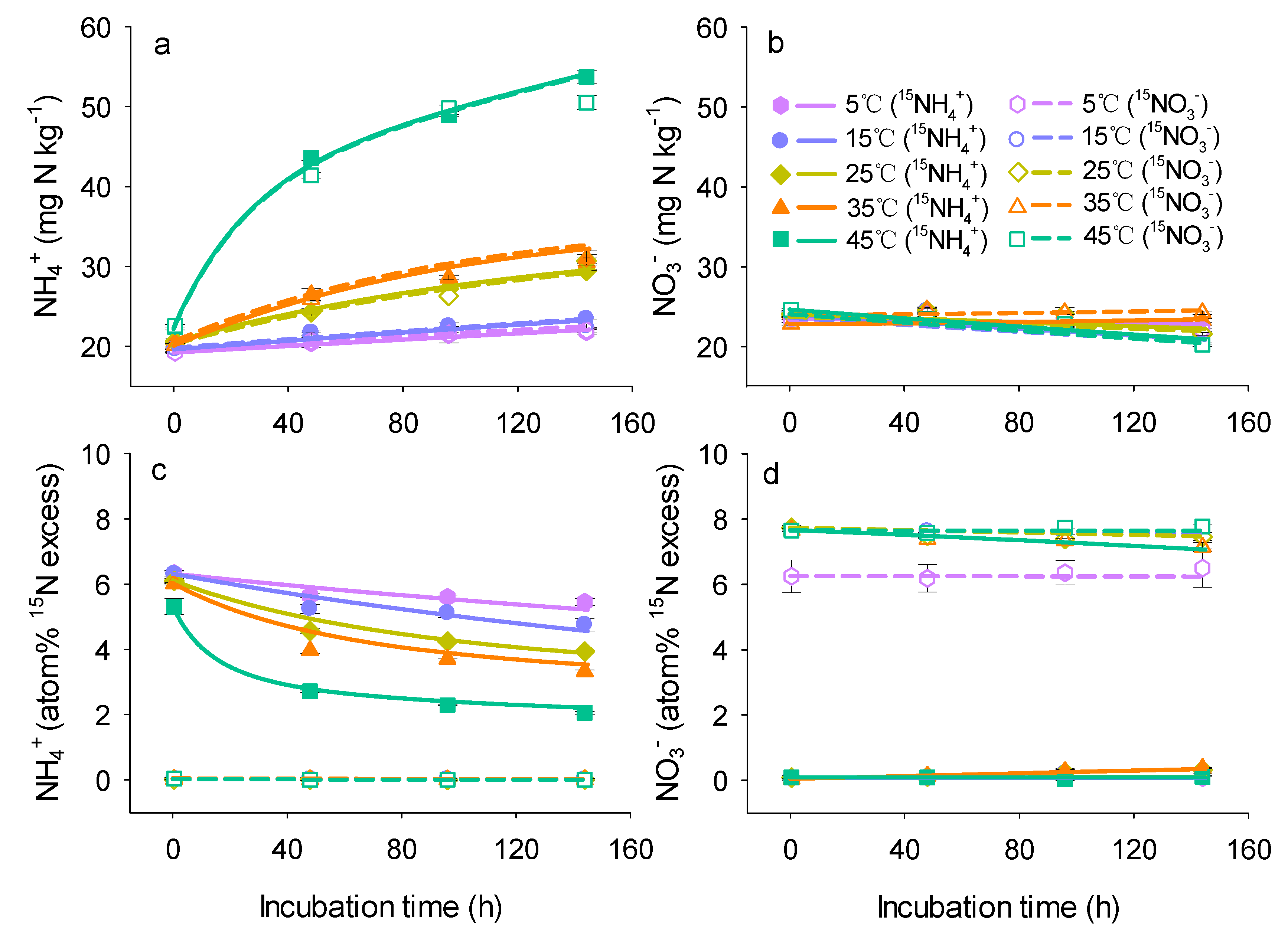

3.1. Changes in Concentrations and 15N Enrichments of Mineral N

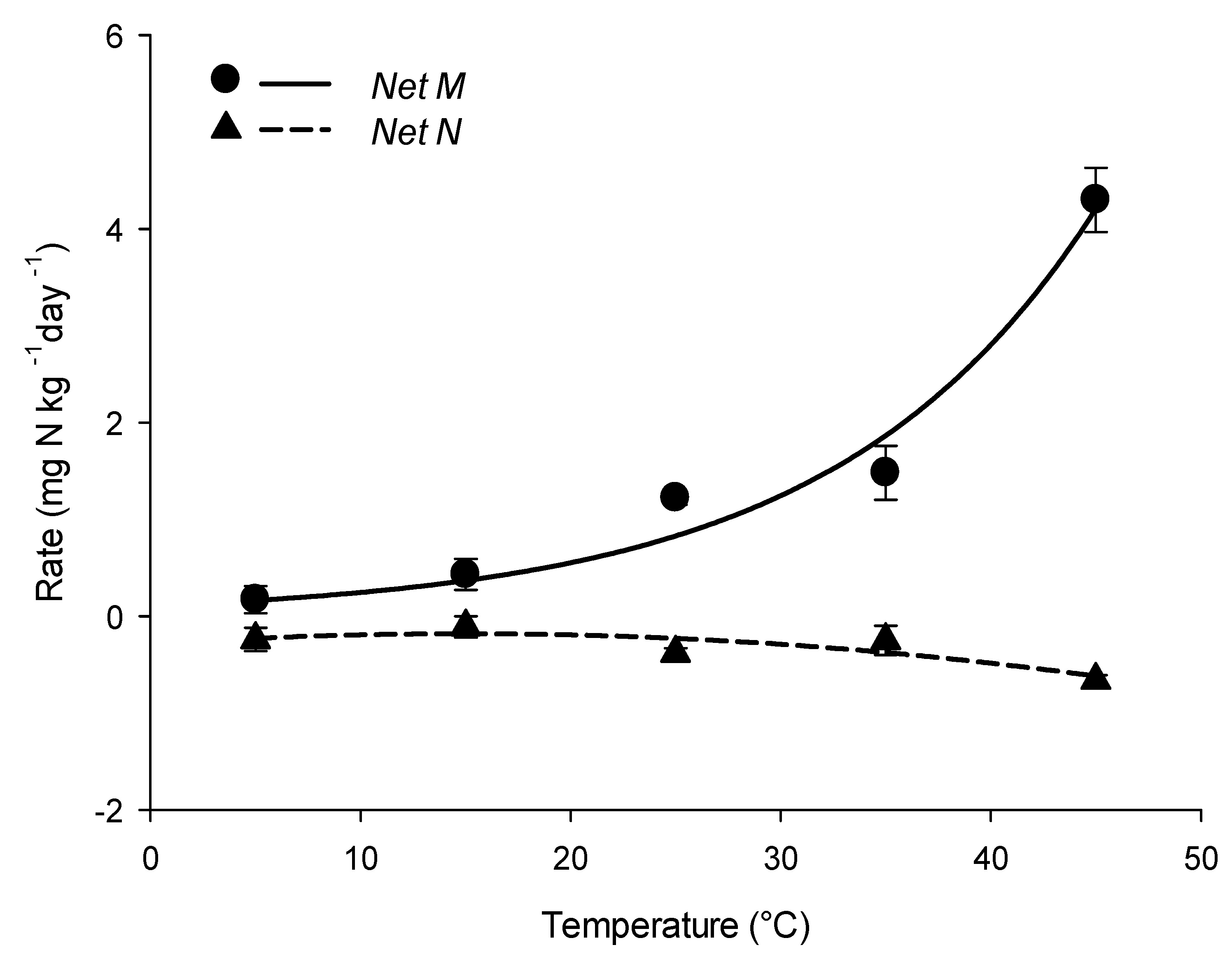

3.2. Influences of Temperature on Net N Transformation Rates

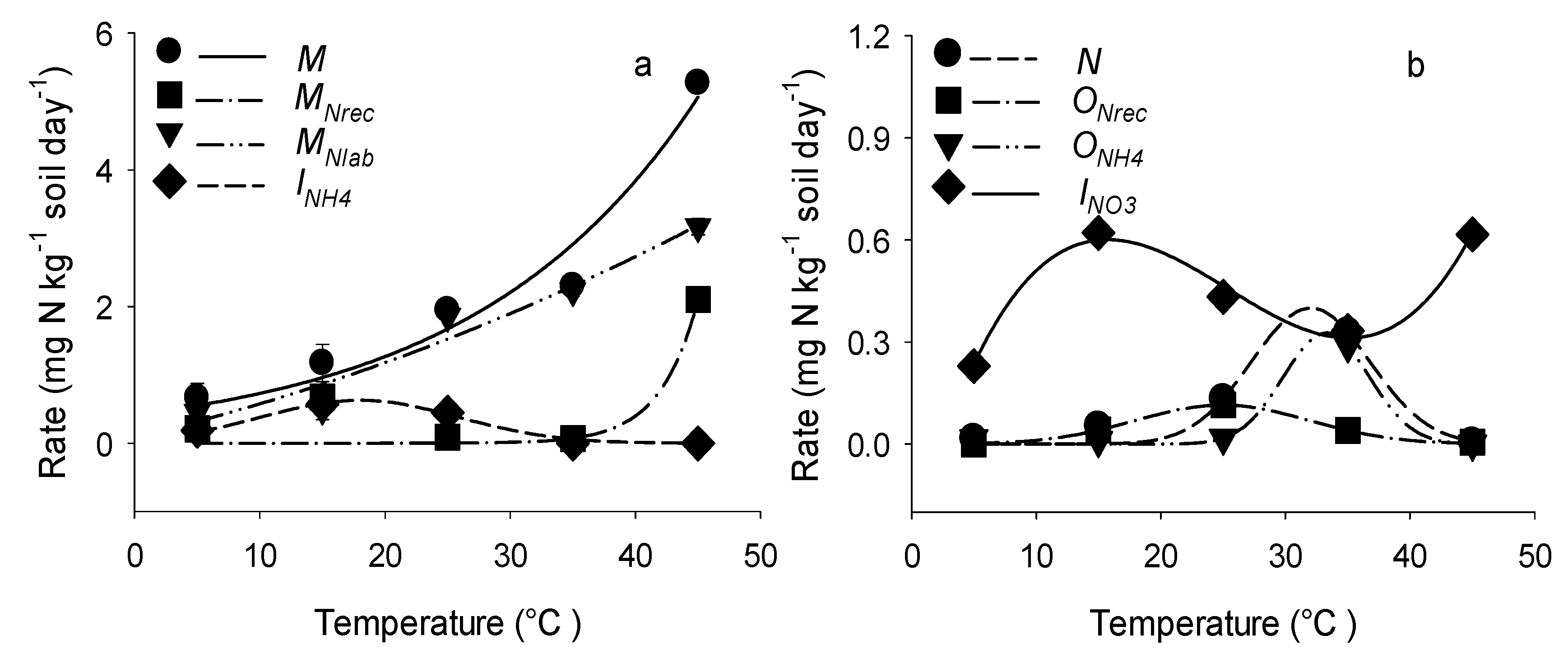

3.3. Influences of Temperature on Gross N Transformation Rates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Compton, J.E.; Boone, R.D. Soil nitrogen transformations and the role of light fraction organic matter in forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templer, P.; Findlay, S.; Lovett, G. Soil microbial biomass and nitrogen transformations among five tree species of the Catskill Mountains, New York, USA. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergensen, R.G.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. Survival of the soil microbial biomass at elevated temperatures. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1990, 22, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Grenon, F.; Bradley, R.L.; Titus, B.D. Temperature sensitivity of mineral N transformation rates, and heterotrophic nitrification: Possible factors controlling the post-disturbance mineral N flush in forest floors. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Cai, Z.C.; Mary, B.; Hao, X.; Chang, S.X. Land-use temperature affect gross nitrogen transformation rates in Chinese and Canadian soils. Plant Soil 2010, 334, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, A.H.; Aber, J.D. Variation in soil net mineralization rates with dissolved organic carbon additions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, S.C.; Nason, G.E.; Myrold, D.D.; Perry, D.A. Dynamics of gross nitrogen transformations in an old-growth forest: The carbon connection. Ecology 1994, 75, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntiñas, M.E.; Leirós, M.C.; Trasar-Cepeda, C.; Gil-Sotres, F. Effects of moisture and temperature on net soil nitrogen mineralization: A laboratory study. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2012, 48, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.B.; Wang, S.Q.; Cai, Z.C. The different temperature sensitivity of gross N transformations between the coniferous and broad-leaved forests in subtropical China. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2015, 61, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huygens, D.; Rütting, T.; Boeckx, P.; Van Cleemput, O.; Godoy, R.; Müller, C. Soil nitrogen conservation mechanisms in a pristine south Chilean Nothofagus forest ecosystem. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 2448–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rütting, T.; Huygens, D.; Müller, C.; Van Cleemput, O.; Godoy, R.; Boeckx, P. Functional role of DNRA and nitrite reduction in a pristine south Chilean Nothofagus forest. Biogeochemistry 2008, 90, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Chang, S.X. Substrate type, temperature, and moisture content affect gross and net N mineralization and nitrification rates in agroforestry systems. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2004, 39, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J.M.; Hart, S.C. High rates of nitrification and nitrate turnover in undisturbed coniferous forests. Nature 1997, 385, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.Y.; Xu, J.M.; Yi, X.; Lin, Y.D. Net and gross nitrification in tea soils of varying productivity and their adjacent forest and vegetable soils. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 58, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, B.; Recous, S.; Robin, D. A model for calculating nitrogen fluxes in soil using 15N tracing. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1998, 30, 1963–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Rutting, T.; Kattge, J.; Laughlin, R.J.; Stevens, R.J. Estimation of parameters in complex 15N tracing models by Monte Carlo sampling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.G.; Xie, W.M.; He, X.Y.; Wang, M.Z. Red Soils of Jiangxi Province; Jiangxi Science and Technology Publishing House: Nanchang, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.K. Soil Agro-Chemical Analyses; Agricultural Technical Press of China: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, P.D.; Stark, J.M.; McInteer, B.B.; Preston, T. Diffusion method to prepare soil extracts for automated nitrogen-15 analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1989, 53, 1707–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Laughlin, R.J.; Christie, P.; Watson, C.J. Effects of repeated fertilizer and slurry applications over 38 years on N dynamics in a temperate grassland soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1362–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, W.J.; Schimel, D.S.; Cole, C.V.; Ojima, D.S. Analysis of factors controlling soil organic matter levels in Great Plains Grasslands. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1987, 51, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insam, H. Are the soil microbial biomass and basal respiration governed by the climatic regime? Soil Biol. Biochem. 1990, 22, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalias, P.; Anderson, J.M.; Bottner, P.; Coûteaux, M.M. Temperature responses of net nitrogen mineralization and nitrification in conifer forest soils incubated under standard laboratory conditions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wan, S.; Xing, X.; Zhang, L.; Han, X. Temperature and soil moisture interactively affected soil net N mineralization in temperate grassland in Northern China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardina, C.P.; Ryan, M.G. Evidence that decomposition rates of organic carbon in mineral soil do not vary with temperature. Nature 2000, 404, 858–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, P.B.; Oleksyn, J.; Modrzynski, J.; Mrozinski, P.; Hobbie, S.E.; Eissenstat, D.M.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Chorover, J.; Chadwick, O.A.; Hale, C.M. Linking litter calcium, earthworms and soil properties: A common garden test with 14 tree species. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, W.R.; Cornforth, I.S.; Rowarth, J.S. Winter soil temperature (2–15 °C) effects on nitrogen transformations in clover green manure amended or unamended soils: A laboratory and field study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Cai, Z.; Wang, L. Effects of temperature change and tree species composition on N2O and NO emissions in acidic forest soils of subtropical China. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.S.; Geisseler, D. Temperature sensitivity of nitrogen mineralization in agricultural soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, D.; Stottlemyer, R.; Saurez, F.; Cortina, J. Soil nitrogen availability in some arctic ecosystems in northwest Alaska: Responses to temperature and moisture. Ecoscience 1994, 1, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, P.; Falkengren-Grerup, U.; Bengtsson, G. Relieving substrate limitation-soil moisture and temperature determine gross N transformation rates. Oikos 2005, 111, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, M.S.; Stark, J.M.; Rastetter, E. Controls on nitrogen cycling in terrestrial ecosystems: A synthetic analysis of literature data. Ecol. Monogr. 2005, 75, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, F.C.; Murphy, D.V.; Fillery, I.R.P. Temperature and stubble management influence microbial CO2-C evolution and gross N transformation rates. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, W.R.; Osman, M.; Marschner, P.; Abaye, D.A.; Clark, I.; Murphy, D.V.; Stockdale, E.A.; Watson, C.A. Controls on soil nitrogen cycling and microbial community composition across land use and incubation temperature. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennenberg, H.; Dannenmann, M.; Gessler, A.; Kreuzwieser, J.; Simon, J.; Papen, H. Nitrogen balance in forest soils: Nutritional limitation of plants under climate change stresses. Plant Biol. 2009, 11, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, H.; Dunkin, K.A.; Firestone, M. The relative importance of autotrophic and heterotrophic nitrification in a conifer forest soil as measured by N tracer and pool dilution techniques. Biogeochemistry 1999, 44, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, W.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Nitrification in acid soils: Micro-organisms and mechanisms. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Suter, H.; He, J.; Hayden, H.; Chen, D. Influence of temperature and moisture on the relative contributions of heterotrophic and autotrophic nitrification to gross nitrification in an acid cropping soil. J. Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 2304–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P.; Overrein, L.; Alexander, M. Formation of nitrite and nitrate by actinomycetes and fungi. J. Bacteriol. 1961, 82, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Doxtader, K.G.; Alexander, M. Nitrification by heterotrophic soil microorganisms. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1966, 30, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitinger, J.P.; Klein, T.M.; Novick, N.J.; Alexander, M. Nitrification and characteristics of nitrifying microorganisms in an Acid Forest Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1985, 49, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.B.; Meng, T.Z.; Zhang, J.B.; Yin, Y.; Cai, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhong, W. Nitrogen mineralization, immobilization turnover, heterotrophic nitrification, and microbial groups in acid forest soils of subtropical China. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2013, 49, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Meng, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, W.; Müller, C.; Cai, Z. Fungi-dominant heterotrophic nitrification in a subtropical forest soil of China. J. Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killham, K. Nitrification in coniferous forest soils. Plant Soil 1990, 128, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.B.; Müller, C.; Zhu, T.B.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, Z. Heterotrophic nitrification is the predominant NO3− production mechanism in coniferous but not broad-leaf acid forest soil in subtropical China. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Zhong, W.; Cai, Z. The substrate is an important factor in controlling the significance of heterotrophic nitrification in acidic forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 76, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, Z.; Müller, C.; Zhang, J. Composition of soil recalcitrant C regulates nitrification rates in acidic soils. Geoderma 2019, 337, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietikäinen, J.; Pettersson, M.; Bååth, E. Comparison of temperature effects on soil respiration and bacterial and fungal growth rates. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 52, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, T.G. Termites and the soil environment. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1988, 6, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Cai, Z.C.; Xu, Z.H. Does ammonium-based N addition influence nitrification and acidification in humid subtropical soils of China? Plant Soil 2007, 297, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, T.; Cai, Z.; Müller, C. Nitrogen cycling in forest soils across climate gradients in Eastern China. Plant Soil 2011, 342, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.J.; Conrad, R. Bacteria rather than Archaea dominate microbial ammonia oxidation in an agricultural soil. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 1658–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.M.; Offre, P.R.; He, J.Z.; Verhamme, D.T.; Nicol, G.W.; Prosser, J.I. Autotrophic ammonia oxidation by soil thaumarchaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 17240–17245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ouyang, Y.; Norton, J.M.; Stark, J.M. Ammonium availability and temperature control contributions of ammonia oxidizing bacteria and archaea to nitrification in an agricultural soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 113, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.E.; Giguere, A.T.; Zoebelein, C.M.; Myrold, D.D.; Bottomley, P.J. Modeling of soil nitrification responses to temperature reveals thermodynamic differences between ammonia-oxidizing activity of archaea and bacteria. ISME J. 2017, 11, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, P.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, C.; Xiong, Z. Thermodynamic responses of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria explain N2O production from greenhouse vegetable soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M.; Richards, B.N. Effect of reforestation on turnover of 15N-labelled nitrate and ammonia in relation to changes in soil microflora. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1977, 9, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.E.; Schimel, D.S.; Firestone, M.K. Short-term partitioning of ammonium and nitrate between plants and microbes in an annual grassland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1989, 21, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recous, S.; Machet, J.M.; Mary, B. The partitioning of fertiliser-N between soil and crop: Comparison of ammonium and nitrate applications. Plant Soil 1992, 144, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, D.R.; Groffman, P.M.; Pregitzer, K.S.; Christensen, S.; Tiedje, J.M. The vernal dam: Plant-microbe competition for nitrogen in northern hardwood forests. Ecology 1990, 71, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Stark, J.M.; Firestone, M.K. Microbial production and consumption of nitrate in an annual grassland. Ecology 1990, 71, 1968–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Hart, S.C.; Firestone, M.K. Internal cycling of nitrate in soils of a mature coniferous forest. Ecology 1992, 73, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.E.; Billings, S.A.; Lane, C.S.; Li, J.; Fogel, M.L. Warming alters routing of labile and slower-turnover carbon through distinct microbial groups in boreal forest organic soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 60, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Willems, A.B.; Lanigan, G.J.; Clough, T.J.; Andresen, L.C.; Müller, C. Long-term elevation of temperature affects organic N turnover and associated N2O emissions in a permanent grassland soil. Soil 2016, 2, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter 1 | Equations |

|---|---|

| M | |

| MNlab | |

| MNrec | |

| INH4 | |

| N | |

| ONrec | |

| ONH4 | |

| INO3 | |

| Net M | |

| Net N |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dan, X.; Chen, Z.; Dai, S.; He, X.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Müller, C. Effects of Changing Temperature on Gross N Transformation Rates in Acidic Subtropical Forest Soils. Forests 2019, 10, 894. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100894

Dan X, Chen Z, Dai S, He X, Cai Z, Zhang J, Müller C. Effects of Changing Temperature on Gross N Transformation Rates in Acidic Subtropical Forest Soils. Forests. 2019; 10(10):894. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100894

Chicago/Turabian StyleDan, Xiaoqian, Zhaoxiong Chen, Shenyan Dai, Xiaoxiang He, Zucong Cai, Jinbo Zhang, and Christoph Müller. 2019. "Effects of Changing Temperature on Gross N Transformation Rates in Acidic Subtropical Forest Soils" Forests 10, no. 10: 894. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100894

APA StyleDan, X., Chen, Z., Dai, S., He, X., Cai, Z., Zhang, J., & Müller, C. (2019). Effects of Changing Temperature on Gross N Transformation Rates in Acidic Subtropical Forest Soils. Forests, 10(10), 894. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100894