Abstract

This paper offers a systematic literature review of age-related disparities in the adoption of digital payment systems, a phenomenon that is becoming increasingly relevant as financial transactions become predominantly digital. Using the SPAR-4-SLR protocol, 66 scholarly contributions published between 2014 and 2024 are examined and categorised into four thematic clusters: demographic determinants, behavioural drivers, structural barriers linked to the grey digital divide, and emerging insights from neurofinance. The review highlights a multifactorial set of barriers that limit older adults’ engagement with digital payments, including usability challenges, cognitive and physical limitations, digital skill gaps, and perceived security risks. These obstacles are further amplified by structural inequalities such as socio-economic status, geographic location, and infrastructural constraints. While digital payments are often presented as tools of inclusion, the findings underscore the risk of exclusion for ageing populations without tailored design and policy interventions. The review also identifies areas for further research, particularly at the intersection of ageing, cognitive function, and human–technology interaction, proposing a research agenda that supports more inclusive and age-responsive financial innovation.

1. Introduction

The benefits of the digital age, such as cost savings, increased efficiency, and improved overall well-being, are well documented in the literature (Goldfarb & Tucker, 2019; Goolsbee & Klenow, 2006; Jorgenson et al., 2008).

The swift digitalisation of financial systems has significantly altered the manner in which individuals engage with payments, with digital payment platforms often serving as the gateway to digital finance (Panetta & Leo, 2022). The integration of digital payments into everyday life has helped many users—especially those who were initially reluctant—to mitigate distrust and technological resistance, fostering greater confidence and ease in the use of digital tools. Moreover, the popularity of digital payment systems has increased significantly, driven by their perceived simplicity and operational efficiency—trends that were notably accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which served as a catalyst for their widespread adoption across diverse demographic groups and geographic regions (Baviskar et al., 2023; Saha & Kiran, 2022). Nevertheless, this promising digital transition has also revealed persistent inequalities in the acceptance and adoption of new technologies, shaped along demographic variables such as age, education, gender, and socio-economic status (Colline et al., 2022; M. A. Khan, 2021).

However, access to these benefits remains unevenly distributed, particularly for those without internet access or digital literacy abilities (Forman et al., 2005, 2012; Goldfarb & Prince, 2008). Older adults are particularly susceptible to what has been called the “grey digital divide” (Y. Zhang et al., 2024), leading to significant social and financial consequences that impact their overall well-being, health, and quality of life (Fox & Connolly, 2018; Miller & Tucker, 2011; Tarricone et al., 2022). More specifically, the term “grey digital divide” refers to a specific form of digital exclusion that affects older adults, particularly in relation to access, skills, motivation, and confidence in using digital technologies (Mubarak & Suomi, 2022). Unlike the general digital divide, which often focuses on infrastructural gaps, the grey digital divide emphasises cognitive, emotional, and generational barriers that disproportionately affect ageing populations in the context of digital transformation (Chee, 2024). This concept provides a crucial analytical lens for understanding how age intersects with broader technological, social, and behavioural inequalities (Diana et al., 2025).

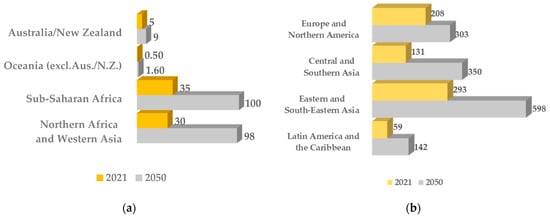

The world is undergoing a profound demographic transformation, marked by an unprecedented acceleration in population ageing. In this context, understanding intergenerational dynamics is therefore essential for addressing disparities in access and fostering the development of inclusive and resilient financial ecosystems. Advancing research in this field is essential, particularly to inform the development of digital financial solutions and public policies aiming to bridge the digital divide and ensure equitable access to financial services. This situation poses challenges for governments in addressing the needs of an ageing population (Yao et al., 2021). The share of people aged 60 and over is projected to increase significantly, rising sharply from approximately 12% in 2020 to over 20% by 2050 (Doerr et al., 2022; Vollset et al., 2020). This trend (see Figure 1a,b) is evident across advanced economies, emerging markets, and developing economies, driven by increased life expectancy and persistent reductions in fertility rates.

Figure 1.

Number of people aged 65 years or above (millions) by region (2021 and 2050). Source: UN (2023). (a) Regions with fewer than 50 million people aged 65 and over in 2021 and 2050 (projections). (b) Regions with 50 million or more people aged 65 and over in 2021 and 2050 (projections).

The expansion of the elderly population is reshaping economic and financial systems worldwide. Among the sectors that are most affected, digital payment systems—which underpin virtually all daily transactions—stand out as particularly crucial. As societies transition toward digital economies, ensuring that no one is left behind becomes imperative. A truly inclusive digital transformation must address the specific needs of older adults, fostering accessibility, trust, and ease of use within payment ecosystems. For instance, initiatives aiming at promoting digital literacy among older adults often fall short due to high costs and a lack of confidence in technology (Forman et al., 2012; Helsper & Reisdorf, 2017). This situation calls for tailored interventions that address these vulnerabilities in a targeted and sustainable way. Understanding these intergenerational dynamics is vital for addressing digital accessibility inequalities among older people and for designing effective aged care systems. To create truly inclusive, customer-centred financial systems, it is essential to understand how individual characteristics shape engagement with digital payments and to identify factors that are particularly relevant for older users. By acknowledging the diverse needs of different demographic groups, digital payment systems can be better suited to integrating accessibility, usability, and an enhanced overall user experience. Despite growing attention, significant gaps remain in our understanding of how age, along with other demographic factors, affects perceptions of the acceptability and use of digital payment systems in different contexts. There is no integrated data that provides an overall picture, although certain factors, such as age and income, have been examined individually (Lohana & Roy, 2023; Said et al., 2021). Moreover, the existing evidence tends to focus heavily on individual countries (e.g., India or Sweden), limiting the generalisability of the results. To address these gaps, this study conducts a comprehensive systematic literature review, guided by the following main research question (RQ):

RQ: What role does age—particularly among older adults—play in shaping the adoption and use of digital payment systems?

To explore this issue comprehensively, the study addresses two key sub-research questions:

- RQ1: What are the main barriers (e.g., lack of trust, usability issues, security concerns) preventing elderly people from adopting digital payment systems?

- RQ2: How does the digital divide (e.g., lack of digital literacy, limited internet access) contribute to the difficulties that elderly people face in adopting digital payment systems?

By focusing on this crucial theme, we aim to generate valuable insights that could encourage governments, policymakers, and financial institutions to develop initiatives tailored to older users. Such initiatives would help to bridge the digital access gap, particularly for senior citizens, and promote equitable access to digital financial services for all demographic groups.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 outlines the methodology adopted, detailing the SPAR-4-SLR protocol for assembling, arranging, and assessing the relevant literature. Section 3 presents the main findings from the systematic review, organised into thematic clusters. Finally, Section 4 concludes by outlining policy recommendations and avenues for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

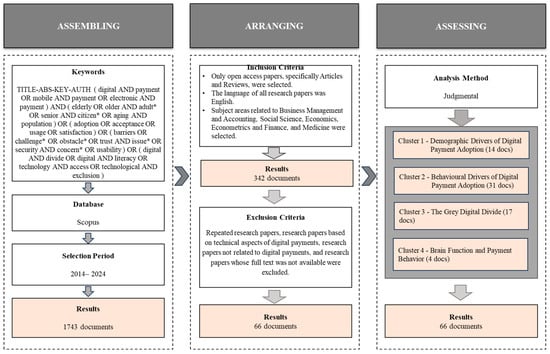

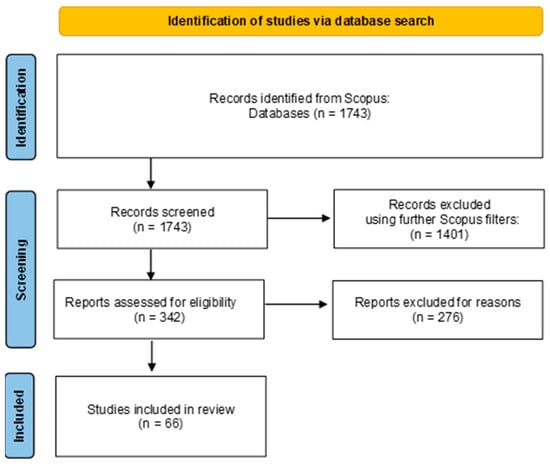

This paper analyses research trends in the domain of digital payments, aiming at understanding the role of age in influencing the adoption and use of these systems, especially among older adults. Employing an integrated methodological framework, the study combines elements of cumulative research analysis with a systematic literature review (SLR) covering an extensive timeframe. The SLR approach follows a transparent, structured, and reproducible protocol (Akello et al., 2022; Lim & Weissmann, 2023; Rao et al., 2023), allowing researchers to systematically evaluate the existing literature, highlight prevailing research trends, identify knowledge gaps, and suggest viable future research directions (Lim et al., 2021). While various frameworks exist for conducting systematic literature reviews (Paul et al., 2021), this study aligns with the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; (Moher et al., 2015) to ensure transparency, replicability, and rigour in reporting, as documented in Appendix A. However, to guide the analytical stages of the review and structure the synthesis of the results, we adopt the SPAR-4-SLR protocol (He et al., 2024; S. Kumar et al., 2024; Paul et al., 2021). SPAR-4-SLR provides a structured, process-orientated framework articulated in three phases—assembling, arranging, and assessing—which supports methodological coherence, minimises bias, and facilitates the generation of robust, generalisable insights. The integration of both protocols ensures a transparent reporting process (via PRISMA) and a rigorous, thematically structured analysis (via SPAR-4-SLR). Specifically, during the “assembling” stage, relevant literature was systematically identified and collected. In the “arranging” stage, the sample was refined by applying predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, the “assessing” stage involved analysing and synthesising the selected studies, which enabled the categorisation of existing research into four principal thematic clusters. Figure 2 provides a visual summary of this methodological framework, with further details provided in the subsequent paragraphs.

Figure 2.

The methodological flowchart used for reviewing the literature on digital payment adoption by the elderly, adhering to the SPAR-4-SLR protocol. Notes: “TS”, such as “topic” in Web of Science, refers to searches for topic terms in the following fields within a record: title, abstract, author keywords, and keywords plus. The asterisk (*) serves as a truncation operator in Scopus search queries, enabling the retrieval of all terms that share the same initial root but differ in their endings.

The Assembling Step: Once the research questions (RQ1 and RQ2) had been clearly defined, relevant keywords were identified to guide the search for scholarly contributions aligned with the study’s objectives (Figure 2). Specifically, the search terms included combinations of keywords such as “digital payment*”, “elderly”, “older adult*”, “ageing population”, “technology adoption”, “financial inclusion”, and “digital divide” (see Figure 2 for the string used). Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to refine the query, and truncation symbols (*) ensured the inclusion of variations (e.g., “payment”, “payments”).

Scopus was selected as the primary database due to its extensive coverage of scholarly work in the domain of digital payments, thereby reducing the likelihood of omitting significant references. Search queries were then systematically developed and refined, based on prior studies on digital payment such as that by Panetta et al. (2023), leading to the initial identification of fewer than 2000 articles. To enhance methodological rigour and ensure a comprehensive literature retrieval process, an additional author-based search was conducted, as recommended by Donthu et al. (2021). This cross-validation step served to confirm that the keyword-driven search strategy effectively captured the core contributions of leading scholars in the field. Specifically, this author-based search involved identifying key scholars frequently cited in the domain of digital payment adoption and ageing, based on highly cited articles and reference co-occurrence across the initial search results. We manually reviewed the publication records of these authors in Scopus, using their author IDs to retrieve additional potentially relevant papers. This step helped to confirm that the keyword-based search had not missed central contributions and ensured alignment with the most active academic voices in the field.

The timeframe from 2014 to 2024 was selected to ensure the relevance and timeliness of the literature reviewed. Over the past decade, the adoption and development of digital payment systems have accelerated significantly, driven by rapid technological innovation, widespread smartphone penetration, and shifts in consumers’ behaviour. Furthermore, this period captured the transformative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which profoundly impacted the use of digital payments across all age groups and brought particular attention to the challenges and opportunities faced by elderly users. Limiting the analysis to this timeframe ensured that the findings would reflect the most recent technological, social, and regulatory developments shaping digital payment adoption.

The Arranging Step: Applying defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, the initial sample of 1743 articles was reduced to a final sample of 66 scholarly contributions. In particular, the first round of filtering (inclusion criteria), based on Scopus’s built-in filters, retained only articles published in English and classified under the subject areas of Business, Management and Accounting, Social Science, Economics, Econometrics and Finance, and Medicine. This step effectively excluded technical contributions from unrelated fields. To ensure academic quality, only peer-reviewed journal articles and review papers were included, while conference proceedings and book chapters were excluded. The inclusion criteria required that studies (i) were published in peer-reviewed journals between 2014 and 2024; (ii) were written in English; (iii) addressed the adoption or use of digital payment systems; and (iv) explicitly mentioned age or generational aspects. The exclusion criteria eliminated conference proceedings, book chapters, non-English papers, and contributions unrelated to the behavioural or demographic analysis of payment systems. Articles that addressed broader fintech themes without a clear reference to payments or age were also excluded during full-text screening.

The inclusion of the “Medicine” subject area was deemed appropriate due to the study’s specific focus on the population. Relevant studies exploring behavioural economics, neuroeconomics, and the adoption of digital financial tools by older adults are often published in interdisciplinary medical journals, particularly those addressing cognitive function, health-related financial decision-making, and technological use in later life. Including this category thus allowed for a more comprehensive examination of the intersection between health sciences and economic behaviour.

To further enhance the credibility and accessibility of the selected documents, we retained only open access papers that adhered to institutional editorial standards. As our primary aim was to explore the relationship between digital payments and age, an additional filter retained only papers that explicitly referenced both terms. After applying Scopus’s open access filter and confirming full-text availability, 342 relevant articles published between 2014 and 2024 were identified. We then examined abstracts and full texts to eliminate off-topic studies, yielding a final sample of 66 articles.

The Assessing Step: The papers included in the final sample were thoroughly analysed and synthesised through a full-text reading process. Subsequently, the final stage of the study systematically explored the selected articles by examining both their abstracts and main texts, following specific interpretative pathways identified through cluster analysis. After the full-text reading process, we reviewed the main conceptual and methodological characteristics of each study (e.g., research focus, dependent and independent variables, analytical framework, country coverage) and tabulated them to assess their alignment with the emerging themes of the review. This allowed us to group the contributions into coherent analytical clusters, thus ensuring a structured synthesis consistent with both the SPAR-4-SLR protocol and PRISMA guidelines.

Given the relatively limited size of the final sample (66 articles), a judgemental clustering approach was adopted. Unlike statistical clustering techniques, which are typically suited to large datasets but are prone to generating unstable or less meaningful groupings in smaller samples, this qualitative, judgement-based categorisation allowed for a more nuanced and meaningful interpretation of the literature, better capturing thematic commonalities and emerging trends. Through this process, four thematic clusters were identified. Three clusters emerged as predominant: (i) Demographic Drivers of Digital Payment Adoption, (ii) Behavioural Drivers of Digital Payment Adoption, and (iii) The Grey Digital Divide. In addition, a fourth cluster, (iv) Brain Function and Payment Behaviour, was identified. Although comprising a smaller number of contributions, this final cluster was deliberately highlighted due to its significant potential for informing future research directions, reflecting the authors’ strategic assessment of its relevance. To support the synthesis of the results, we systematically tabulated the key characteristics and findings of each study—including the topic, country, dependent and independent variables, and methodological approach—and organised them into structured summary tables for each thematic cluster. This tabular presentation facilitated comparison across studies and enhanced the clarity of the review. Where appropriate, we also developed visual tools (e.g., conceptual maps, cluster diagrams) to highlight thematic relationships and strand-level differences among the included papers. The results of the cluster analysis are summarised in dedicated tables, which tabulate the key characteristics and findings of each study included in the review. This systematic presentation facilitates comparison across thematic groups and supports transparency and replicability, in line with PRISMA recommendations. As this review followed a qualitative synthesis approach without performing meta-analytical calculations, no formal statistical methods were applied to assess the risk of bias due to missing results (e.g., publication bias). However, we sought to mitigate potential reporting bias through a comprehensive literature search, clearly defined inclusion/exclusion criteria, and transparent documentation of the screening and synthesis process. Given the qualitative nature of this systematic literature review, no formal statistical methods (e.g., GRADE) were used to assess the certainty of the evidence. However, efforts were made to ensure a robust and credible synthesis by adopting a transparent protocol (SPAR-4-SLR), triangulating findings across clusters, and relying on peer-reviewed, open access articles selected through well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3. Results

This section synthesises and critically discusses the key findings of the systematic literature review, organised around four thematic clusters. Each cluster represents a distinct yet interconnected strand of research concerning the use of digital payment systems by older adults. The clusters are discussed in dedicated subsections, where the main contributions of the papers included are summarised, compared, and critically interpreted. This structure facilitates a deeper understanding of both the prevailing insights and the gaps within the existing literature. Following the cluster-specific discussions, a synthesis is presented that explicitly aligns the findings of the review with the two guiding research questions (RQ1 and RQ2). This integrative analysis draws on insights from all four thematic clusters to offer a comprehensive response to the research questions. The synthesis also outlines key implications for future research, policy, and practice, with particular emphasis on designing inclusive, age-sensitive digital financial systems. While no formal statistical tools were applied to assess the risk of bias due to missing results, the review minimised such risks through a comprehensive and transparent inclusion strategy. Furthermore, although we did not apply formal frameworks such as GRADE, confidence in the body of synthesised evidence is supported by the robustness and consistency of the findings across multiple thematic strands. This strengthens the interpretability of the results discussed in the following sections. Although no formal statistical methods were applied to assess the risk of bias due to missing results, the comprehensive search strategy and transparent inclusion criteria aimed to minimise potential reporting biases.

3.1. Cluster 1: Demographic Drivers of Digital Payment Adoption

This cluster gathers 14 studies published between 2008 and 2024, with a notable concentration of contributions emerging after 2021. Geographically, the majority of research in this area is conducted in India, which accounts for nearly 60% of the total number of studies. This reflects the country’s rapid evolution in digital payment adoption, particularly in the wake of significant financial and technological transitions. While several studies within this cluster explore age-related differences in digital payment behaviour, the overall scope extends to a broader demographic perspective, encompassing factors such as education, income, gender, technological access, and exposure to awareness programmes. This diversity underscores the multifaceted nature of demographic influences on digital financial engagement. As highlighted in the literature review by Colline et al. (2022), digital payments offer benefits across generation lines, from Generation Z to Baby Boomers (see Table 1 for the definition of different generations). This generational breadth suggests that digital payment systems possess wide demographic appeal, enhancing their relevance and attractiveness across diverse user segments.

Table 1.

Definition of generations: characteristics and useful references.

Age and generational factors are the central themes in the studies by A. Kumar and Lim (2008) and Lohana and Roy (2023), both of which demonstrate that generational differences significantly influence perceptions, and satisfaction with, digital payment systems. In particular, older cohorts—such as Baby Boomers—tend to exhibit slower adoption rates compared to younger generations. Similarly, Saha and Kiran (2022) highlight that older adults often require stronger support structures, such as enhanced security, usability, and targeted education initiatives, to facilitate their transition toward digital financial practices. Collectively, these contributions underscore the importance of allowing sufficient time for older individuals to learn and adapt to digital payment technologies. They also point to the critical role of user-friendly interfaces and dedicated instructional support in promoting adoption among senior users. The findings reinforce the need for inclusive design principles and intergenerational learning strategies to ensure that older adults are not excluded from the digital financial ecosystem. Beyond age, education and income levels emerge as critical enablers of digital payment adoption. Studies by Behera et al. (2023) and Said et al. (2021) demonstrate that individuals with higher educational attainment and greater income levels are more likely to adopt and maintain the use of digital payments. Similarly, Baviskar et al. (2023) and Saroy et al. (2022) emphasise how external factors—such as smartphone accessibility, government initiatives, and the recent pandemic—have widened digital payment adoption, particularly among better-connected and better-informed populations. Behera et al. (2023) further report a notable shift in digital payments after the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly among more educated and wealthier individuals, reflecting an evolving financial transaction landscape. Additionally, Andaregie et al. (2024) analyse nationally representative data from Ethiopia, identifying mobile device ownership, ATM/debit card access, and internet connectivity as pivotal technological enablers for digital payment adoption. Their findings reinforce the idea that socio-economic factors, such as education, income, and financial inclusion, significantly influence the likelihood of adopting digital financial services, further highlighting the intersection between technological access and demographic characteristics.

Other studies delve into the intersection of multiple demographic dimensions and their collective impact on digital payment adoption. Research by M. A. Khan (2021), Jaiswal et al. (2022), and Lohana and Roy (2023) indicates that a confluence of characteristics, such as age, gender, education, and marital status, shapes users’ perceptions of service quality, security, satisfaction, and loyalty with digital payment systems. These studies emphasise that digital payment experiences are not solely influenced by a single demographic variable, but are instead the result of complex interactions between various socio-demographic factors. Additionally, some studies address issues of digital exclusion and inequality. Sanchez-Diaz et al. (2021) highlight that older and marginalised populations faced significant barriers to accessing online financial services during the COVID-19 pandemic. This underscores the importance of addressing digital divides and ensuring that all demographic groups have equitable access to digital financial services, particularly in times of crisis. Table 2 summarises the key studies included in cluster 1.

Table 2.

Cluster 1: Demographic influences on digital payment adoption (alphabetical order).

While demographic characteristics, such as age and income, play a significant role in the adoption of digital payment systems, their influence is often mediated by psychological and behavioural variables. The next cluster explores these behavioural dimensions in greater depth, relying on theoretical frameworks such as the TAM and UTAUT to understand users’ intentions and decision-making processes.

3.2. Cluster 2: Behavioural Drivers of Digital Payment Adoption

This cluster consists of 31 studies published between 2016 and 2024, all of which employ structured behavioural models—primarily the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)—to investigate the factors influencing digital payment adoption. Unlike the previous cluster, which was organised around demographic categories, this cluster is structured according to the theoretical frameworks employed to analyse users’ behavioural intentions. The majority of the studies within this cluster are recent, reflecting the growing scholarly attention on digital financial adoption, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A substantial body of research in this cluster systematically identifies perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness as consistent and reliable determinants of digital payment adoption (general behavioural determinants identified through the TAM and UTAUT). Core studies supporting these findings include those by Tang et al. (2021) and Daştan and Gürler (2016), both of which confirm that practical benefits and simplicity are pivotal drivers of users’ intention to adopt digital payments. These results are echoed by Sivathanu (2019) and Sholihah and Ariyani (2023), who apply similar models across different demographic and geographic contexts.

Concerns regarding privacy, perceived risk, and trust emerge prominently as mediating factors influencing adoption behaviour. Kamal et al. (2023) and Zhong and Moon (2022) find that security concerns—particularly among older adults and less digitally confident users—significantly reduce trust and adoption intentions. Similarly, Ebubedike et al. (2022) and J. Zhang et al. (2019) show that interface design, perceived control, and risk aversion play a crucial role in shaping users’ adoption behaviours.

Additionally, several studies in cluster 2 identify social factors and external support as significant predictors of digital payment adoption. Poudel et al. (2023), Al Arif et al. (2023), Sutresna et al. (2023), Patil et al. (2020), and, more recently, Purwanto et al. (2023) demonstrate that family, community, and cultural environments can enhance the acceptability of digital financial technologies. This evidence is particularly important in contexts where collective norms or traditions influence user behaviour, underscoring the need for culturally sensitive interventions.

Age emerges as a recurrent theme across several studies (age as a critical factor in behavioural intentions), highlighting the nuanced ways in which different generations approach digital payment technologies. Research by Zhu et al. (2023) extended the Theory of Planned Behaviour to model elderly users’ digital payment intentions during COVID-19, revealing that older individuals experienced heightened perceived risk and were more dependent on intergenerational support for adoption. Similarly, Berraies et al. (2017), Santosa et al. (2021), and Thoumrungroje and Suprawan (2024) provide evidence that Baby Boomers and Generation X prioritise usability, security, and functionality, revealing a more cautious and pragmatic approach compared to younger cohorts. Findings across studies suggest that older adults’ acceptance of digital payments is less influenced by trendiness or innovation, and more by clear functionality, trustworthiness, and the ease of integrating new systems into established routines. This pattern underscores the necessity of designing digital financial products that cater specifically to the cognitive, emotional, and experiential profiles of older users. Santosa et al. (2021) and Thoumrungroje and Suprawan (2024) find that age serves as a strong moderator of intention and satisfaction, with older adults valuing usability and stability over novelty or trendiness.

A distinct, well-defined substream within this cluster pertains to the impact of COVID-19 on digital payment adoption. The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst for digital payment adoption, accelerating usage and producing significant behavioural shifts. Sutresna et al. (2023) documented how social influences and performance expectations shaped adoption behaviours in rural Indonesia during the pandemic. Beura et al. (2023) focused on the role of perceived experience in promoting the sustained intention of digital payment users in India’s post-pandemic environment. Zhu et al. (2023) similarly framed their exploration within a pandemic context, emphasising how external shocks modified perceived risks and motivational factors, particularly among elderly users. Chaveesuk et al. (2022) and Sutresna et al. (2023) further noted that social distancing considerations contributed to increased digital payment usage, particularly by enhancing perceived ease of use and satisfaction, in line with the TAM. Niankara and Traoret (2023) extended this observation to a global perspective, linking financial inclusion efforts during the pandemic to an uptick in digital payment adoption.

However, a more critical examination of the existing literature suggests that while the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital payment systems among older adults, this shift was largely driven by necessity, rather than by a genuine readiness to embrace digital technologies. For many, the increased usage of digital tools mainly reflected a pragmatic response to the temporary unavailability of physical alternatives, rather than an enduring transformation in digital trust or behaviour. Empirical evidence indicates that, once in-person services resumed, a proportion of older users reverted to traditional payment methods, such as cash or branch-based banking, highlighting the fragility of behavioural change when it is not supported by adequate digital literacy, accessible interface design, and emotional reassurance.

Moreover, the crisis exposed stark inequalities: older adults with higher levels of education or a strong intergenerational support network adapted more easily, whereas those from lower socio-economic backgrounds or with limited prior exposure to digital tools often encountered heightened levels of stress, confusion, or even exclusion. These findings highlight that crisis-driven adoption does not equate to long-term inclusion. The most pronounced and persistent behavioural shifts were observed in settings where government policy, technology infrastructure, and social support systems aligned to reduce barriers and incentivize adoption. However, significant barriers—especially psychological- and trust-related barriers—remain for a subset of older adults, and regional disparities persist. The long-term sustainability of these behavioural shifts will likely depend on continued support, infrastructure development, and targeted interventions to address remaining barriers. Consequently, policy design and interventions must address these deeper, structural barriers to ensure that digital engagement among older adults is both sustainable and equitable.

In addition to the drivers discussed, several studies address the socio-economic and infrastructural enablers of digital payment adoption (socio-economic contexts and digital literacy). Petrikova and Kocisova (2024) and Purwanto et al. (2023) demonstrate a nonlinear relationship between age and digital payment adoption across the Euro Area, reinforcing the view that structural conditions significantly mediate behavioural intentions. Similarly, financial literacy, digital infrastructure, and service accessibility are stressed as pivotal conditions for expanding adoption rates (Patnaik et al., 2023; Purwanto et al., 2023; Seldal & Nyhus, 2022). A lack of digital skills, even among financially literate users, is repeatedly cited as a key barrier that needs tailored interventions. These insights further highlight how generational divides interact with broader structural factors to influence digital payment behaviours. This stream suggests that perceived behavioural control, though often framed as psychological, is deeply influenced by material conditions.

Taken together, the findings in this cluster (detailed in Table 3) suggest that the intention to adopt and continue using digital payment systems is shaped by a dynamic interplay of technological perceptions (ease of use, usefulness, security), social and environmental influences, digital literacy, and macro-level shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Importantly, while traditional TAM and UTAUT models remain robust explanatory frameworks, newer models increasingly incorporate contextual factors such as crisis environments, infrastructural readiness, and generational divides. Future efforts to promote digital payment adoption, particularly among older adults, must thus adopt multifaceted strategies that simultaneously address psychological, infrastructural, and social barriers.

Table 3.

Cluster 2: Behavioural models and determinants of digital payment usage (alphabetical order).

Behavioural drivers, however, do not operate in isolation. They are often shaped by broader contextual and structural constraints, which are especially pronounced among older adults. The third cluster addresses this concern by shifting the focus from individual-level behavioural factors to systemic barriers, such as limited access, inadequate infrastructure, and socio-economic disparities—collectively referred to as the grey digital divide.

3.3. Cluster 3: The Grey Digital Divide: Structural Barriers to Digital Engagement Among Older Adults

This cluster brings together 17 studies (see Table 4) that investigate the persistent challenges that older adults face in accessing and utilising digital technologies. Although these studies do not exclusively focus on digital payments, they provide critical insights into the structural and socio-economic barriers shaping older individuals’ broader digital engagement. Understanding these broader obstacles is essential to addressing RQ2 in particular, which explores the factors limiting the adoption of digital payment systems among elderly populations. Indeed, the reduced use of digital financial services by older adults cannot be fully explained without considering their limited access to the internet, lower levels of digital literacy, reduced motivation, and social or infrastructural constraints. The contributions in this cluster thus highlight how the grey digital divide—defined by gaps in skills, access, and empowerment among the elderly—is deeply intertwined with issues of income, education, cultural context, geographic disparities, and policy environments. Although the studies cover a wide range of digital inclusion topics, they collectively inform the understanding of why older populations remain underrepresented in the digital payment ecosystem.

Table 4.

Cluster 3: Key studies on age-related digital exclusion and structural barriers (alphabetical order).

A key insight emerging from the reviewed contributions is the central role of age in driving digital inequality. Older adults are systematically disadvantaged in accessing and effectively using digital tools, even in technologically advanced contexts. Research by Brandtzaeg et al. (2011) and Friemel (2016) illustrates that the elderly, compared to younger cohorts, display lower rates of digital engagement, with this disparity being heavily influenced by education levels, income, and private social support. Similarly, Hargittai et al. (2019) and Helsper and Reisdorf (2017) demonstrate that digital skills among older individuals in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Sweden are unevenly distributed along socio-economic lines, suggesting that lower education and income significantly exacerbate the risk of digital exclusion.

Beyond age, these studies also emphasise the amplifying effects of socio-economic, cultural, and contextual barriers. Findings from Kaila (2023) and Yang and Du (2020) highlight that older adults from minority and rural backgrounds—such as in Vietnam and China—face compounded disadvantages due to limited educational opportunities, lower socio-economic capital, and restricted access to smart technologies. Deursen and Van Dijk (2019) further argue that even in environments with high levels of infrastructural availability, like the Netherlands, persistent disparities in digital skills reflect deeper structural inequalities that internet access alone cannot resolve. Furthermore, Brink (2024) critiques the design of e-government systems, pointing out that assuming high digital literacy levels unintentionally excludes older users unless specific support strategies are implemented.

Another significant dimension explored in this cluster is the link between digital engagement, health, and well-being. Research by Hunsaker and Hargittai (2018) shows that digital activities contribute positively to older adults’ well-being and health. However, access to these benefits remains heavily mediated by socio-economic conditions. Studies by Rosenberg (2024) and Yao et al. (2021) highlight the heightened vulnerability of digitally excluded seniors to online risks, such as fraud or social isolation, particularly in crisis contexts like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, several contributions emphasise the need for multidimensional strategies to promote digital inclusion among the elderly. Raihan et al. (2024) propose intersectional approaches that integrate affordable internet provision, culturally sensitive digital education, and community-based interventions to address the root causes of exclusion. Mohan and Lyons (2024) provide empirical evidence from Ireland, showing that access to high-speed broadband facilitates more frequent and meaningful online engagement among older users, although motivational and skills-related barriers persist. Similarly, Audrin and Audrin (2022) advocate for embedding digital literacy within broader educational policies, while Lythreatis et al. (2021) emphasise the importance of monitoring socio-economic trends that dynamically reshape the contours of digital inequality. Taken together, these findings portray the grey digital divide as a complex and evolving phenomenon where age interacts profoundly with socio-economic, cultural, and infrastructural factors. Addressing this divide requires more than just expanding access; it necessitates integrated, context-sensitive strategies that simultaneously empower older adults with the skills, confidence, and motivation to participate fully in digital life—including, crucially, in the domain of digital financial services. Beyond individual digital skills and age-related factors, socio-economic and regional disparities significantly influence both access to and usage of digital payment systems. Lower-income individuals often encounter multiple layers of exclusion: limited access to smartphones, unreliable internet connections, and a lack of familiarity with app-based interfaces. These challenges are further compounded in rural or economically peripheral areas, where the decline of traditional banking infrastructure is not complemented by proportional investments in digital financial literacy or support mechanisms.

Several studies within this cluster highlight the uneven nature of digital readiness, showing that the mere presence of infrastructures does not adequately guarantee effective adoption. Individuals with lower levels of education or income frequently perceive digital payments as either insecure or irrelevant to their needs. Moreover, regional disparities often mirror broader patterns of economic marginalisation, resulting in entire communities being underserved by both traditional and digital financial services. These factors interact with age and technological familiarity in complex ways, creating cumulative barriers that disproportionately impact older adults in socio-economically disadvantaged contexts.

While structural barriers shape the external conditions for adoption, internal cognitive and neuropsychological factors also play a critical role, particularly among older adults. The final cluster explores emerging insights from neurofinance to shed light on how cognitive ageing influences financial decision-making, including digital payment behaviour.

3.4. Cluster 4: Brain Function

This cluster explores the emerging relationship between cognitive processes and payment behaviour, with a particular focus on older adults (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cluster 4: Key studies on neuroscientific and cognitive perspectives on payment behaviour (alphabetical order).

Neurofinance is an interdisciplinary field that combines insights from neuroscience, psychology, and behavioural economics to investigate how individuals make financial decisions. Unlike behavioural finance, which focuses on observed deviations from rational choice, neurofinance seeks to understand the underlying cognitive and neural mechanisms—such as attention, memory, emotional regulation, and reward processing—that drive financial behaviour. In the context of digital payment adoption, neurofinance offers a useful lens to explore how cognitive ageing influences the ways in which older adults perceive, trust, and interact with digital financial tools. In the context of digital payment adoption, neurofinance provides a valuable framework for analysing how cognitive ageing affects user engagement, particularly in relation to interface design, learning capacity, and digital confidence.

Among the studies reviewed, only four contributions directly address payment behaviour or financial decision-making processes relevant to payment contexts. Most existing neuroeconomic research has concentrated on areas such as investments, credit evaluations, and financial market behaviour, underscoring the need to extend neuroscientific approaches to everyday financial transactions.

Cognitive functions such as memory, attention, impulsivity, and executive function play a fundamental role in shaping individuals’ payment preferences and behaviour, especially in populations experiencing cognitive ageing. Age-related cognitive decline can manifest in various ways, such as reduced working memory, difficulty in managing multitasking, diminished inhibitory control, and slower decision-making. These changes increase the cognitive effort required to navigate digital interfaces—especially those that involve multi-step procedures, verification processes, or small-screen reading. As a result, even when older adults have access to digital payment tools, they may avoid using them due to the perceived complexity and mental fatigue associated with their use.

The contribution by Miendlarzewska et al. (2019) is particularly relevant in this context. By integrating insights from psychology, neuroscience, and finance, it demonstrates that emotional responses, cognitive biases, stress, and individual differences significantly influence financial decision-making. These mechanisms are particularly salient in digital contexts, where rapid interactions with interfaces and constant notifications can overwhelm users with lower cognitive resilience. In addition, A. Khan and Mubarik (2020) propose that neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin modulate trust and impulsivity—two key dimensions that influence whether individuals perceive digital payments as secure and reliable or as risky and confusing.

Ceravolo et al. (2019) add a complementary perspective, showing how visual attention is modulated by design elements (e.g., colour) and personality traits such as impulsivity. Their findings suggest that digital payment interfaces—if poorly designed—can hinder comprehension and reduce confidence in completing a transaction. This is especially relevant for older adults, who may already be operating with reduced attentional capacity and who are disproportionately affected by unclear layouts, small fonts, and fast interaction flows.

Sudirjo et al. (2023) further support these insights by demonstrating that cognitive motivations, such as perceived convenience, reduced cognitive effort, and practical utility, drive the adoption of digital wallets. For older users, platforms that minimise cognitive friction and simplify the payment process are more likely to be adopted and retained over time. Their findings align with broader behavioural trends indicating that simplification and perceived ease of use significantly influence the transition toward digital financial ecosystems, particularly among individuals affected by cognitive decline.

The limited number of studies within this cluster highlights a notable gap in the current literature. While substantial progress has been made in documenting behavioural drivers and structural inequalities, the neurocognitive mechanisms that underpin how older adults engage with digital financial tools remain underexplored. Bridging this gap is essential not only for advancing theoretical understanding, but also for informing the development of inclusive technological solutions. Regulators, financial service providers, and developers should incorporate principles of cognitive ergonomics into the design process, by promoting usability testing with ageing users and adopting design standards that account for age-related changes in perception, memory, and attention. Aligning financial innovation with neurocognitive inclusivity is essential to ensuring that the digital transition does not exacerbate age-related disparities in access and engagement.

According to the available evidence, this strand of the literature appears both underexplored and increasingly compelling. We believe that, by applying neuroeconomic approaches to the study of everyday payment, behaviour represents a highly promising frontier for future research. Investigating how cognitive ageing influences the acceptance and use of digital payment systems compared to cash payment systems could yield critical insights for designing more inclusive and cognitively adaptive financial technologies.

4. Discussion: Barriers, Digital Divide, and Strategies for Inclusion

The systematic review of the literature has identified several interconnected barriers that hinder the adoption of digital payment systems among senior citizens, directly addressing both RQ1 and RQ2. Technological challenges remain a major obstacle, with many older adults struggling to use digital payment applications that feature complex interfaces, requiring high cognitive effort to navigate. These technological barriers are compounded by age-related cognitive and physical limitations, such as memory decline, reduced vision, and decreased manual dexterity (Chee, 2024). In addition, security and privacy concerns introduce a substantial psychological barrier. Fears of fraud, personal data breaches, and a general mistrust towards digital systems are commonly reported by older users as key reasons for their resistance to the adoption (Dimitrova et al., 2021; Saha & Kiran, 2022). This combination of factors creates a sense of perceived vulnerability, which undermines users’ willingness to adopt new payment technologies, even when, technically, access is available.

Socio-economic differences also exert a decisive influence in shaping digital payment behaviours among the elderly. Variations in income, education level, and broader financial inclusion significantly affect not only access to digital infrastructures, but also the ability to understand and confidently engage with digital financial services (Andaregie et al., 2024; Hargittai et al., 2019; Helsper & Reisdorf, 2017; Kaila, 2023; Lythreatis et al., 2021; Raihan et al., 2024). These findings reinforce the notion that adoption challenges are not merely technological or cognitive, but are deeply rooted in broader patterns of social and economic inequality.

The digital divide emerges as a structural factor that spans technological, skill-based, and motivational dimensions. Access-related divides—manifested in the limited availability of smartphones, broadband connectivity, and reliable internet services—are particularly pronounced for older adults in rural or underserved areas (Andaregie et al., 2024; Aurazo & Vega, 2021; Colline et al., 2022). Even when physical access is available, many elderly users are hindered by a skills divide, struggling with a lack of digital literacy and difficulty in acquiring new digital competences (Aurazo & Vega, 2021; Deursen & Van Dijk, 2019; Hargittai et al., 2019). However, the motivational divide appears equally critical. Older adults often express a low perceived usefulness of digital payment technologies and resistance to changing well-established payment habits, even when technical barriers are reduced (Ahmad et al., 2020; Beura et al., 2023; Sholihah & Ariyani, 2023; Zhong & Moon, 2022). This suggests that simply improving infrastructure and skills may not be sufficient, unless accompanied by efforts to reshape attitudes and expectations towards digital financial tools.

The literature also outlines several strategic pathways to facilitate greater inclusion. Improving digital literacy through targeted educational programmes emerges as a necessary step, aiming not only to teach technical skills, but also to build confidence and trust in digital systems. Moreover, the design of digital payment technologies must evolve to be more age-friendly, leveraging intuitive navigation, larger fonts, and even voice-activated systems to accommodate the cognitive and physical needs of elderly users. In parallel, community support mechanisms such as peer mentoring and localised training sessions can play a key role in fostering adoption by creating trusting, supportive environments for learning and experimentation.

In conclusion, the findings show that elderly individuals’ engagement with digital payment systems is influenced by a complex interaction of technological, cognitive, motivational, and socio-economic factors. Addressing these barriers through multidimensional strategies—such as technological redesign, targeted education, policy incentives, and community engagement—is essential for bridging the digital gap and promoting equitable access to financial innovations.

To support the synthesis of findings, Table 6 summarises the key barriers identified in the literature and links them to the corresponding research questions. The evidence is categorised across technological, cognitive, social, and infrastructural domains, offering a structured view of how these factors inhibit or shape digital payment adoption among older adults. Each entry highlights the underlying issue, references supporting authors, and outlines the practical strategies proposed in the reviewed studies. By consolidating the core insights from all clusters, this table serves as a bridge between the detailed literature review and the broader implications for policy and future research.

Table 6.

Mapping insights from the literature to RQ1 and RQ2: key findings and suggested interventions.

Before concluding, it is worth acknowledging some limitations of both the reviewed evidence and the review process itself. The studies examined vary considerably in terms of geographic focus, methodology, and target populations—many are limited to specific national contexts or lack long-term perspectives. Although the review followed a structured and transparent protocol, the exclusion of non-English literature and grey sources may have left out valuable insights. That said, the results provide useful guidance for both policy and practice: they highlight the urgent need to rethink digital payment ecosystems with an age-inclusive lens and open up promising directions for future research—particularly around cognitive ageing and the design of more supportive technologies.

5. Conclusions

This systematic literature review set out to explore the relationship between ageing and digital payment adoption by uncovering the complex interplay of behavioural, demographic, and structural factors that shape older adults’ engagement with financial technologies. As digital payments become the default mode of transaction in many societies, ensuring that ageing populations are not excluded is both a social imperative and a technological challenge.

Our findings suggest that age itself is not a barrier, but rather a lens through which various vulnerabilities—such as low digital literacy, reduced cognitive agility, and socio-economic inequality—are magnified. The evidence shows that older adults are not unwilling to adopt digital financial tools; rather, their engagement is often hindered by inaccessible design, perceived risk, and a lack of tailored support. These barriers are compounded by broader divides in access, skills, and motivation, creating a stratified digital landscape in which elderly individuals often remain marginalised.

By organising the literature into four thematic clusters, this study highlights both the progress made and the gaps that remain. While behavioural models such as the TAM and UTAUT have provided a solid foundation for understanding user intentions, they often overlook the lived realities of ageing—realities marked by changing physical, emotional, and social dynamics. Similarly, while some efforts have been made to document the grey digital divide, fewer studies take a systemic view of how age-related exclusion emerges at the intersection of policy, technology, and human cognition.

What emerges clearly is that inclusive digital finance is not only a matter of infrastructure or access, but of empathy in design, foresight in policymaking, and sustained investment in digital capacity building. Age-friendly interfaces, intergenerational support networks, and community-based digital education programmes are not optional add-ons, but essential components of an equitable digital ecosystem.

In sum, ageing in a digital society requires more than technological adaptation—it calls for a rethinking of how we define usability, trust, and inclusion in financial innovation. Sustained investment in building digital capacity must be informed by rigorous, user-centred research. Future studies could explore the following questions:

- How do specific cognitive factors (e.g., memory retention, attentional control, decision fatigue) influence the usability of and trust in digital payment platforms among users aged 65 and over?

- What role do interface complexity and visual design features play in shaping digital payment behaviour across different cognitive ageing profiles?

- To what extent can intergenerational learning environments or peer-support interventions mitigate cognitive barriers to adoption?

These research directions could be pursued using mixed-methods designs that combine neuropsychological assessments (e.g., working memory tasks, cognitive load measures) with usability testing, eye-tracking experiments, or longitudinal interviews. Such approaches would help to bridge the gap between behavioural insights and practical design implications for inclusive financial technology.

In light of these findings, future research should not only explore the long-term impact of educational and policy interventions, but also embrace interdisciplinary approaches that account for cognitive, emotional, and social factors influencing digital engagement.

Among the most promising research frontiers, the emerging strand of neurofinance holds particular potential to shed light on how cognitive ageing shapes payment behaviour, offering new insights into decision-making processes and helping to inform the design of cognitively adaptive financial technologies for older users. Bridging the grey digital divide is not solely a matter of technological innovation; it is also a question of social inclusion and justice. Ensuring equitable access to financial technologies across all generations is a necessary condition for building truly inclusive digital societies.

Future research would benefit from more longitudinal, comparative, and interdisciplinary approaches, especially those that combine insights from economics, psychology, gerontology, and human–computer interaction. Only then can we ensure that digital transformation lives up to its promise: improving lives across all ages, without leaving anyone behind.

The findings of this review also carry significant practical and policy implications. Financial service providers and digital platform designers are encouraged to adopt age-sensitive usability standards that account for cognitive and emotional challenges that are commonly experienced by older adults. Policymakers should avoid one-size-fits-all digital inclusion strategies, and instead develop tailored interventions that account for local infrastructure deficiencies, income inequalities, and the distinct digital habits of different generational cohorts. Furthermore, the review highlights the value of participatory design and intergenerational learning programmes as effective tools for building trust in digital finance. Collectively, these implications advocate for a shift from purely access-oriented models of inclusion towards more human-centred, equity-driven approaches to digital payment innovation.

Building on these insights, we identify three policy priorities directly linked to the barriers outlined in this review. First, governments and regulatory agencies should promote the development of digital payment platforms that incorporate rigorous usability testing with older adults, ensuring accessibility for individuals experiencing cognitive decline or sensory impairments. Second, targeted interventions are imperative in rural and low-income areas where the reduction of physical banking infrastructure has not been compensated by investments in digital education programmes or infrastructure. Potential measures include developing mobile support units, establishing community-based digital finance advisors, and funding publicly accessible help desks. Third, policy frameworks should incentivize both formal and informal intergenerational mentoring initiatives that empower younger users to support elderly family members or neighbours in managing digital financial tasks. These actionable strategies aim to translate the study’s findings into measurable steps toward a more inclusive and equitable digital payment ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, I.C.P. and E.A.; methodology, I.C.P.; validation, S.L. and P.P.; formal analysis, S.L., P.P. and E.A.; investigation, S.L., P.P. and E.A.; data curation, I.C.P. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, —review and editing, I.C.P., S.L., P.P. and E.A.; writingsupervision, I.C.P.; project administration, I.C.P.; funding acquisition, I.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article is the result of research activities supported by funding from Sapienza University of Rome under the following grant numbers: RP12117A7CC99031, RG1241910F40A9AE and AR124190789BE01E. In addition, Elaheh Anjomrouz’s contribution was funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU, Mission 4, Component 1, CUP B53C23002550006.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the selection of the included studies.

References

- Ahmad, A., Rasul, T., Yousaf, A., & Zaman, U. (2020). Understanding factors influencing elderly diabetic patients’ continuance intention to use digital health wearables: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM). Journal of Open Innovation Technology Market and Complexity, 6(3), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akello, P., Beebe, N. L., & Choo, K.-K. R. (2022). A literature survey of security issues in cloud, fog, and edge IT infrastructure. Electronic Commerce Research, 25(2), 705–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Arif, M. N. R., Nofrianto, N., & Fasa, M. I. (2023). The preference of muslim young generation in using digital zakat payment: Evidence in Indonesia. Al-Uqud: Journal of Islamic Economics, 7(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, A. A., Al-Okaily, M., Shiyyab, F. S., Taha, A. A., Almajali, D. A., Masa’deh, R., & Warrad, L. H. (2024). Determinants of digital payment adoption among Generation Z: An empirical study. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(11), 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaregie, A., Abebe, G. K., Gupta, P., Worku, G., Matsumoto, H., Astatkie, T., & Takagi, I. (2024). Exploring individuals’ socioeconomic characteristics and digital infrastructure determinants of digital payment adoption in Ethiopia. Digital Business, 4(2), 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrin, C., & Audrin, B. (2022). Key factors in digital literacy in learning and education: A systematic literature review using text mining. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 7395–7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurazo, J., & Vega, M. (2021). Why people use digital payments: Evidence from micro data in Peru. Latin American Journal of Central Banking, 2(4), 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basid, R., & Atmaja, J. (2022, March 31–April 1). The effect of generation Z workforce characteristics on the gig economy with work life integration as a mediator. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Contemporary Risk Studies, ICONIC-RS 2022, Jakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baviskar, R., Patil, P., Deokota, S., Sharma, A., & Mandal, A. (2023). An assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on digital payments by households. International Journal of Management and Business Intelligence, 1(2), 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, R. R., Saroy, R., & Dhal, S. (2023). Digital payments in urban odisha: Insights from a primary survey. Review of Development and Change, 28(2), 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencsik, A., Juhász, T., & Horvath-Csikos, G. (2016). Y and Z generations at workplaces. Journal of Competitiveness, 6, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraies, S., Yahia, K. B., & Hannachi, M. (2017). Identifying the effects of perceived values of mobile banking applications on customers: Comparative study between baby boomers, generation X and generation Y. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(6), 1018–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beura, D., Naveen, L., Prusty, S. K., Nanda, A. P., & Rout, C. K. (2023). Digital payment continuance intention using mecm: The role of perceived experience. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(6), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtzaeg, P., Heim, J., & Karahasanovic, A. (2011). Understanding the new digital divide—A typology of Internet users in Europe. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 69, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, S. (2024). E-government impact on the grey digital divide. Gerontechnology, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbeck, C. (2012). Imagining the future: Young australians on sex, love and community (pp. 1–288). Cambridge University Press (CUP). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceravolo, M., Cerroni, R., Farina, V., Fattobene, L., Leonelli, L., Mercuri, N., & Raggetti, G. (2019). Attention allocation to financial information: The role of color and impulsivity personality trait. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaveesuk, S., Khalid, B., & Chaiyasoonthorn, W. (2022). Continuance intention to use digital payments in mitigating the spread of COVID-19 virus. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 6, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, S. Y. (2024). Age-related digital disparities, functional limitations, and social isolation: Unraveling the grey digital divide between baby boomers and the silent generation in senior living facilities. Aging & Mental Health, 28(4), 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colline, F., Furinto, A., & Kartono M, R. (2022, August 16–18). Digital payment adoption: Review of literature. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management (pp. 1895–1909), Warangal, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danisman, G. O., & Tarazi, A. (2020). Financial inclusion and bank stability: Evidence from Europe. The European Journal of Finance, 26(18), 1842–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D. K. K., & Mahapatra, R. (2020). Customer perception towards payment bank: A case study of cuttack city (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3524162). Social Science Research Network. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3524162 (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Daştan, İ., & Gürler, C. (2016). Factors affecting the adoption of mobile payment systems: An empirical analysis. EMAJ: Emerging Markets Journal, 6(1), 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deursen, A. J. A. M., & Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2019). The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media & Society, 21, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, M. G., Mascia, M. L., Tomczyk, Ł., & Penna, M. P. (2025). The digital divide and the elderly: How urban and rural realities shape well-being and social inclusion in the sardinian context. Sustainability, 17(4), 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, I., Öhman, P., & Yazdanfar, D. (2021). Barriers to bank customers’ intention to fully adopt digital payment methods. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 14(5), 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, S., Frost, J., Gambacorta, L., & Qiu, H. (2022). Population ageing and the digital divide. SUERF Policy Briefs, 270, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebubedike, A. H., Mohammed, T. A., Nellikunnel, S., & Teck, T. S. (2022). Factors influencing consumer’s behavioural intention towards the adoption of mobile payment in Kuala Lumpur. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 7(6), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, C., Goldfarb, A., & Greenstein, S. (2005). How did location affect adoption of the commercial Internet? Global village vs. urban leadership. Journal of Urban Economics, 58(3), 389–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, C., Goldfarb, A., & Greenstein, S. (2012). The internet and local wages: A puzzle. American Economic Review, 102(1), 556–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G., & Connolly, R. (2018). Mobile health technology adoption across generations: Narrowing the digital divide. Information Systems Journal, 28(6), 995–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friemel, T. (2016). The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New Media & Society, 18, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A., & Prince, J. (2008). Internet adoption and usage patterns are different: Implications for the digital divide. Information Economics and Policy, 20(1), 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A., & Tucker, C. (2019). Digital economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 57(1), 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolsbee, A., & Klenow, P. J. (2006). Valuing consumer products by the time spent using them: An application to the internet. American Economic Review, 96(2), 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E., Piper, A. M., & Morris, M. (2019). From internet access to internet skills: Digital inequality among older adults. Universal Access in the Information Society, 18, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P., Wang, T.-Y., Shang, Q., Zhang, J., & Xu, H. (2024). Knowledge mapping of e-commerce supply chain management: A bibliometric analysis. Electronic Commerce Research, 24(3), 1889–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E. J., & Reisdorf, B. C. (2017). The emergence of a “digital underclass” in great Britain and Sweden: Changing reasons for digital exclusion. New Media & Society, 19(8), 1253–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsaker, A., & Hargittai, E. (2018). A review of Internet use among older adults. New Media & Society, 20, 3937–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D., Kaushal, V., Mohan, A., & Thaichon, P. (2022). Mobile wallets adoption: Pre-and post-adoption dynamics of mobile wallets usage. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 40(5), 573–588. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, D. W., Ho, M. S., & Stiroh, K. J. (2008). A retrospective look at the U.S. productivity growth resurgence. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(1), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-S., & Yoon, H.-H. (2021). Generational effects of workplace flexibility on work engagement, satisfaction, and commitment in South Korean deluxe hotels. Sustainability, 13, 9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaila, H. (2023). Ethnic digital divide? Evidence on mobile phone adoption. Applied Economics, 55(22), 2536–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, I., Rizki, R. N., & Aulia, M. R. (2023). The enthusiasm of digital payment services and millennial consumer behaviour in Indonesia. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(2), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., & Mubarik, M. (2020). Measuring the role of neurotransmitters in investment decision: A proposed constructs. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A. (2021). Netizens’ perspective towards electronic money and its essence in the virtual economy: An empirical analysis with special reference to Delhi-NCR, India. Complexity, 2021(1), 7772929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., & Lim, H. (2008). Age differences in mobile service perceptions: Comparison of generation Y and baby boomers. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(7), 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Sharma, D., Rao, S., Lim, W. M., & Mangla, S. K. (2024). Correction to: Past, present, and future of sustainable finance: Insights from big data analytics through machine learning of scholarly research. Annals of Operations Research, 332(1–3), 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Li, D., He, S., Sun, S., Tian, Y., & Wang, Z. (2022). The effect of big data-based digital payments on household healthcare expenditure. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 922574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., & Kostka, G. (2024). Navigating the digital age: The gray digital divide and digital inclusion in China. Media, Culture & Society, 46(6), 1181–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., & Weissmann, M. A. (2023). Toward a theory of behavioral control. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 31(1), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., Yap, S.-F., & Makkar, M. (2021). Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: What do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading? Journal of Business Research, 122, 534–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohana, S., & Roy, D. (2023). Impact of demographic factors on consumer’s usage of digital payments. FIIB Business Review, 12(4), 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythreatis, S., El-Kassar, A.-N., & Singh, S. (2021). The digital divide: A review and future research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlutova, I., Spilbergs, A., Verdenhofs, A., Natrins, A., Arefjevs, I., & Volkova, T. (2023). Digital transformation as a driver of the financial sector sustainable development: An impact on financial inclusion and operational efficiency. Sustainability, 15(1), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miendlarzewska, E. A., Kometer, M., & Preuschoff, K. (2019). Neurofinance. Organizational Research Methods, 22(1), 196–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. R., & Tucker, C. E. (2011). Can health care information technology save babies? Journal of Political Economy, 119(2), 289–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G., & Lyons, S. (2024). High-speed broadband availability, Internet activity among older people, quality of life and loneliness. New Media & Society, 26(5), 2889–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., & Prisma-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, F., & Suomi, R. (2022). Elderly forgotten? Digital exclusion in the information age and the rising grey digital divide. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 59, 00469580221096272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabahani, P. R., & Riyanto, S. (2020). Job satisfaction and work motivation in enhancing generation Z’s organizational commitment. Journal of Social Science, 1(5), 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niankara, I. (2023). The impact of financial inclusion on digital payment solution uptake within the gulf cooperation council economies. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 7(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niankara, I., & Traoret, R. I. (2023). The digital payment-financial inclusion nexus and payment system innovation within the global open economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(4), 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocansey, E. N. N. D., Dadzie, P., & Nambie, N. B. (2024). Mobile money use, digital banking services and velocity of money in Ghana. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 14(2), 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panetta, I. C., & Leo, S. (2022). Why are M-payment platforms so attractive? M-payment as the entry level to the digital financial era. Berlino. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panetta, I. C., Leo, S., & Delle Foglie, A. (2023). The development of digital payments–past, present, and future–From the literature. Research in International Business and Finance, 64, 101855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P., Tamilmani, K., Rana, N. P., & Raghavan, V. (2020). Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: Extending Meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust, and grievance redressal. International Journal of Information Management, 54, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A., Kudal, P., Dawar, S., Inamdar, V., & Dawar, P. (2023). Exploring user acceptance of digital payments in India: An empirical study using an extended technology acceptance model in the fintech landscape. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 18(8), 2587–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, I. (2006). Growing older tourism & leisure behaviour of older adults. CABI Digital Library. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., Lim, W. M., O’Cass, A., Hao, A. W., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), O1–O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrikova, T., & Kocisova, K. (2024). Digital payments as an indicator of financial inclusion in Euro Area countries. E+M Ekonomie a Management, 27(2), 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]