Relationships Between Corporate Control Environment and Stakeholders That Mediate Pressure on Independent Auditors in France

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Auditor Independence

2.2. Pressures on Independent Auditors

2.3. Pressure and Corporate Governance

2.4. Underlying Theories Tied to Agency and Neo-Institutional Theory

2.5. The French Auditing Legislative Environment

3. Method

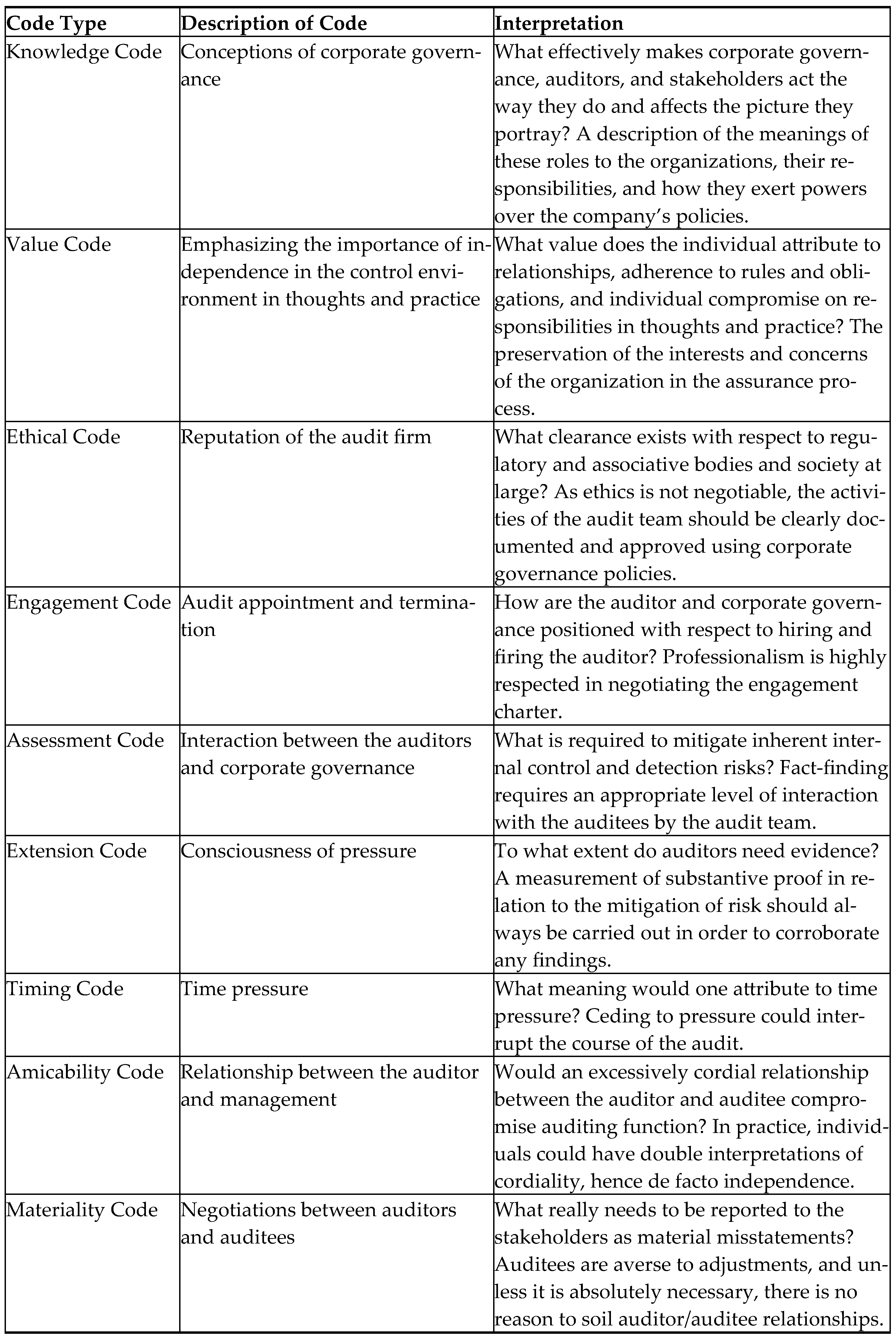

4. Results and Analysis

“The importance of management and the Board are relevant for good corporate governance, I think it is mainly member of Board of directors, CEO or the president, these kinds of persons saying their minds”.(Participant 8)

“I mean for big companies mostly, you have corporate governance elected by the shareholders, and from them, regarding the part of regulation, they are independent from the CEO of the company or CFO, it is an external party”.(Participant 2)

“The Corporate governance we’ll say depends on the environment. It necessarily depends on the environment of the company; it can be then the involvement of auditing committee or the general director. There are different ways of corporate governance. For me is a group of people both operational or in the general direction and in strategic it will be more within the administrators in response to the owners”.(Participant 7)

“… I think the requirements by Deloitte at least and for all big 4 are higher, is more demanding than for other audit firms, so I guess this is because they try to keep better reputation, and it is always better for them to have audit sign by a big 4 than by another audit firm”.(Participant 6)

“Reputation is important, big four has more mechanism and a more developed audit methodology; so they go into more detail of the audit and can use more developed computer tools. But it is also important to support this reputation by being professional and serious at the team level. I will say that reputation does 20% of the work”.(Participant 3)

“… I am working in EY in a report there is a quality, technical and the report is well prepared. Our procedure is much more develop in EY than lower tier auditors, for example, we are doing lots of test and report. In a lower tier firm is only analytical review as I have worked in one, and for EY is a lot of testing to perform internal control tests. For the client, is the same as when you going to buy shoes you will take Adidas or Nike because is a brand, so EY have that quality”.

“At the end, it is the CEO of the company but depends on the size of the company. There is not always corporate governance structure in all firms so, for small companies is the CEO or CFO and they choose who is going to audit. For listed companies, the CFO of the company decide”.(Participant 2)

“I would say it depends. If you are already the auditor is different. But if your auditor gives you too many pains, you can change the auditor. In a very big company, it could be the audit Board, audit committee, but who appoints the audit is the Board actually. My clients were SOX companies. For example, TOTAL, listed in France and in the US. The decision was for audit committee”.(Participant 7)

“…we feel pressure because that guy has enough experience. Is kind of intimidation that the audit team may have, when you are interviewing a more senior position in the organisation, as you do not want to lose the credibility in asking stupid questions, because you know the guy have strong knowledge in the sector. As a senior manager, if I must speak with the CEO, I will ask less questions …”(Participant 6)

“Except for the quality of work, pressures come from the environment, the PCAOB and the French alternatives SCC and auditing enforcement companies, which are so strong on people and processes. There is a lot of pressures on the quality on auditing and if documented in a poor way, that is the kind of pressure I can feel. Pressures come from the regulators”.(Participant 7)

“In France we have 6-year mandated period, so is a long-term relationship. Is very exceptional to get fired during this period. Is to protect the auditors at large”.(Participant 9)

“I have one listed company on which there are lots of pressure, because the financial statement is published on the website and there is a big impact if we do a mistake or if we do not accomplish the deadline. When we have those clients, there are more people working on this entity, is a way to mitigate it, so everybody is on time, we also have more office, because there is much work, so it helps to manage the pressures…”.(Participant 8)

“Yes, because at the end for listed company, the CEO and CFO, would say I want to publish my account on for example February 16, meaning that all your test need to be perform and validated before the 16th of the month. Sometimes you receive the documentation quiet delay and you have very few days to perform all the tests. In that sense, it is quite difficult to be sure at a 100%, that all the accounts are good, that is why you must just look in the main risks accounts”.(Participant 2)

“…you focus on the financial audit in the point of litigation and where maybe force information in the statutory accounts, and once you identify that and you check that, then you have all the section that you can review later but it is maybe not as significant as the other ones”.(Participant 2)

“Concerning the pressure, I pass it on to the person who has to provide me with the documents, I feel a lot of pressure, but on the other hand I put this pressure on the person of the company to give me the right documents”.(Participant 5)

“…Good relationship is a professional relationship, meaning that for me, you need to, know the value. You are not as auditor who is going in a room, ask a lot of questions and at the end, say ok your paper is good. What usually the client like is when you challenge a little bit, when you say ok this, you cannot do this, because therefore due to regulation article 1,2,3”.(Participant 2)

“It may to a certain extent, especially when it comes to understanding the processes and controls. However, being too close might induce lower professional scepticism and hence maybe not targeting possible misstatements”.(Participant 4)

“Extremely. It implies for them to recognize they did some mistakes. They might also disagree because they interpreted accounting standards differently, but interpretation is often an issue”.(Participant 4)

“… If the CFO does not agree to process the adjustments, most of the case, the audit would say ok you do not do it, I sign the accounts, either I put a note in the final report”.(Participant 2)

“…for instance, for litigation you can provide for 100k, in this case, we may propose a figure to the management and will come into agreement at the end either we say ok or on this point we are not 100% sure, we will not propose adjustment”.(Participant 6)

“…we will discuss directly with the accounting team. And if the accounting team does not agree, then there is an issue, we will discuss with the CFO. And if it persists, we will discuss with the CEO and then finally, with the audit committee for example. But most of the time we do agree before the CFO”.(Participant 8)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, L. J., Park, Y., & Parker, S. (2000). The effects of audit committee activity and independence on corporate fraud. Managerial Finance, 26(11), 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L. J., Parker, S., & Peters, G. F. (2004). Audit committee characteristics and financial restatements. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 23(1), 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M. B. (1994). Agency theory and the internal audit. Managerial Auditing Journal, 9(8), 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFEP-MEDEF. (2003). Le gouvernement d’entreprise des sociétés cotées—Principes de gouvernement d’entreprise résultant de la consolidation des rapports conjoints de l’AFEP et du MEDEF de 1995, 1999 et 2002. AFEP-MEDEF. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, L., Cesar, A. M. R. V., & Imoniana, J. O. (2020). The role of attitude and auditee mood during auditing. European Journal of Scientific Research, 156(4), 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Antle, R., & Nalebuff, B. (1991). Conservatism and auditor–client negotiations. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(1), 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, A. A., & Loebbecke, J. K. (1997). Auditing: An Integrated Approach (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, C. R., Bédard, J., & Prat Dit Hauret, C. (2014). The regulation of statutory auditing: An institutional theory approach. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29(5), 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathala, C., & Rao, R. P. (1995). The determinants of board composition: An agency theory perspective. Managerial and Decision Economics, 16(1), 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M., Carcello, J., Hermanson, D., & Neal, T. (2009). The audit Committee oversight process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(1), 65–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M., & Salterio, S. (2001). The relationship between board characteristics and voluntary improvements in the capability of audit committees to monitor. Contemporary Accounting Research, 18(4), 539–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M. S. (1996). An empirical analysis of the relation between the board of director composition and financial statement fraud. The Accounting Review, 71(1), 443–465. [Google Scholar]

- Blue Ribbon Committee (BRC). (1996). Report and recommendations on improving the effectiveness of corporate audit committees. The New York Stock Exchange and The National Association of Securities Dealers. [Google Scholar]

- Boubaker, S., & Labégorre, F. (2008). «Le recours aux leviers de contrôle: Le cas des sociétés cotées françaises». Finance Contrôle Stratégie, 11, 96–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton, D. (2002). Pour un meilleur gouvernement des entreprises cotées—Rapport du groupe de travail présidé par Daniel Bouton. Mouvement des Entreprises de France (MEDEF) & Association Française des Entreprises Privées (AFEP-AGREF). [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(1), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britanica. (2022). Pressure. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/pressure (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti, L. (2004, May 12–14). La normalisation du contrôle interne, esquisse des conséquences organisationnelles de la Loi de Sécurité Financière. 25éme Congrès de l’Association Francophone de Comptabilité, Orléans, France. [Google Scholar]

- Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., Neal, T. L., & Riley, R. A. (2002). Board characteristics and audit fees. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(3), 365–384. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, J. L. (1970). The rise of the accounting profession: To responsibility and authority. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. [Google Scholar]

- Charreaux, G., & Wirtz, P. (2007). Corporate governance in France. Working Paper FARGO N° 1070201. Université de Bourgogne. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, J., Sarens, G., & Leung, P. (2009). A critical analysis of the independence of internal audit function: Evidence from Australia. Accounting, Auditing & Account Journal, 22(2), 200–223. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, F. L., Dean, G. W., & Oliver, K. G. (1997). Corporate collapse: Regulatory, accounting and ethical failure. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. (2002). Corporate governance and the audit process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(4), 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. (2010). Corporate governance in the Posy-Sarbannes-Oxley Era: Auditors’ Experiences. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(3), 751–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. R., Pant, L. W., & Sharp, D. J. (1992). Cultural and socioeconomic constraints on international codes of ethics: Lessons from accounting. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(1), 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P., & Gregory, A. (1996). Audit committee effectiveness and the audit fee. European Accounting Review, 5(2), 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P., & Zaman, M. (2005). Coverngence in Europe Corporate Governance: The audit committee concept. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 13(2), 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maggio, P. J., & Powell, P. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettredge, M., Fuerherm, E., & Li, C. (2014). Fee pressure and audit quality. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 39(4), 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-ALID. (2021). EU audit legislation implementation database. EU-ALID. [Google Scholar]

- Faccio, M., & Lang, L. H. P. (2002). The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of financial Economics, 65, 365–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J. R., Richard, C., & Vanstraelen, A. (2009). Assessing France’s joint audit requirement: Are two heads better than one? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 28(2), 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gephart, R. (2004). Qualitative research and the academy of management journal. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbins, M., Salterio, S., & Webb, A. (2001). Evidence about auditor-client management negotiation concerning clients financial reporting. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(1), 535–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A., & Berlev, B. (1974). The auditor-firm conflect of interest: Its implications for indepewndence. The Accounting Review, 49(4), 707–718. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin-Stewart, J., & Kent, P. (2006). The relation between external audit fees, audit committee characteristics and internal audit. Accounting and Finance, 46(1), 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F. A. (1991). Size of audit fees and perceptions of auditors’ ability to resist management pressure in audit conflict situations. Abacus, 27(2), 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundry, C. L., & Liyanarachchi, A. G. (2007). Time budget pressure, auditors’ personality type, and the incidence of reduced audit quality practices. Pacific Accounting Review, 19(2), 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, J. G. (2000). Organizational culture: Siren or sea cow? A reply to Dianne Lewis. Strategic Change, 9(2), 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoniana, J. O., & Imoniana, B. B. S. (2020). Auditor’s career development and personal identity crisis. European Research Studies Journal, 23(1), 565–586. [Google Scholar]

- Imoniana, J. O., Perers, L. C. J., Lima, F. G., & Antunes, M. T. P. (2011). The dialectic of control culture in SMEs: A case study. International Journal of Business Strategy, 11(2), 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, A. (1993). Audit committees: A guide for non-executive directors. Institute of Chartered Accountants. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Management behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(3), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, T., Margheim, L., & Pattison, D. (2005). An empirical analysis of the effects of auditor time budget pressure and time deadline pressure. Journal of Applied Business Research, 21(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- King, N., & Brooks, J. (2017). Thematic analyss in organizational research. In C. Cassell, A. L. Cunliffe, & G. Grandy (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative business and management research methods (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, B. R., & Leffler, K. (1981). The role of market forces in assuring contractual performance. Journal of Political Economy, 89(4), 615–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macgregor, D., Lichtenstein, S., & Slovic, P. (1988). Structuring KnowledgeRetrieval. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 42(3), 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maule, A. J., & Svenson, O. (1993). Theoretical and empirical approaches to behavioral decision making and their relation to time constraints. In O. Svenson, & A. J. Maule (Eds.), Time pressure and stress in human judgment and decision making. Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, S., Salterio, S. E., & Gibbins, M. (2008). Auditor-client management relationships and roles in negotiating financial reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4–5), 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, L. S. (1990). The effects of time pressure and audit program structure on audit performance. Journal of Accounting Research, 28(1), 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutional organizations: Formal structures as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 80(1), 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D. A., & Loewenstein, G. (2004). Self-interest, automaticity, and the psychology of conflict of interest. Social Justice Research, 17(10), 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D. A., Tetlock, P. E., Tanlu, L., & Bazerman, M. H. (2006). Conflicts of interest and the case of auditor independence: Moral seduction and strategic issue cycling. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 10–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, M. L. (2005). Labour law and new forms of corporate organization. International Labor Review, 144(1), 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M. W. (2006). Ameliorating conflicts of interest in auditing: Effects of recent reforms on auditors and their clients. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, M. N. M., Smith, M., & Ismail, Z. (2009). Auditors’ perception of time budget pressure and reduced audit quality practices: A preliminary study from Malaysian context (Issue 1, pp. 1–11). Journal of Edith Cowan University. [Google Scholar]

- Piot, C. (2005). Auditor reputation and model of governance: A comparison of France, Germany and Canada. International Journal of Auditing, 9(1), 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piot, C., & Janin, R. (2004). Qualité de l’audit, gouvernance et gestion du résultat comptable en France (pp. 12–14). Congrès de l’Association Francophone de Comptabilité. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W. (1991). Expanding the scope of institutional analysis. In The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 183–203). The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Power, M. K. (2003). Auditing and the production of legitimacy. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(4), 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act. (2002). Pub. L. No. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-107publ204/pdf/PLAW-107publ204.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Scott, W. R. (1987). The adolescence of institutional theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32(4), 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spira, L. F. (1999). Ceremonies of governance: Perspectives on the role of audit committees. Journal of Management and Governance, 3(3), 231–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, N. (2002). Understanding media cultures: Social theory and mass communication (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Swedberg, R. (2010). The structure of confidence and the collapse of lehman brothers. In Markets on trial: The economic sociology (pp. 371–414). Emerald. [Google Scholar]

- Umar, A., & Anandarajan, A. (2004). Dimensions of pressures faced by auditors and its impact on auditors’ independence: A comparative study of the USA and Australia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 19(1), 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, V. A. T., & Flecher, P. D. (2023). Twenty years of auditing in France. Dynamics of the audit sphere as a resulto f regulation modes articulation between actors. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04309159v1 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Wright, A., & Wright, S. (1997). An examination of factors affecting the decision to waive audit adjustments. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 12(1), 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, C., & Rwabizambuga, A. (2006). Institutional pressures, corporate reputation, and voluntary codes of conduct: An examination of the equator principles. Business & Society, 111(1), 89–118. [Google Scholar]

| Interviewee | Position | Auditor/Auditee | Enterprise | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G.W. (Participant 1) | Financial Controller | Auditee | IDEMIA France | 7 |

| M.E. (Participant 2) | Senior Manager | Auditor | DELOITTE | 10 |

| L. L. (Participant 3) | Senior Manager | Auditor | EY | 7 |

| B. D. (Participant 4) | Partner | Auditor | DELOITTE | 11 |

| G. R. (Participant 5) | Partner | Auditor | KPMG | 13 |

| P. R. (Participant 6) | Senior Manager | Auditor | DELOITTE | 12 |

| N.P. (Participant 7) | Manager | Auditor | KPMG | 10 |

| M. B. (Participant 8) | Manager | Auditor | EY | 12 |

| A. L. (Participant 9) | Manager | Auditee | Controller | 14 |

| A.D. (Participant 10) | Audit Committee Member | Board Member | IDEMIA France | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carhuapomachacon, G.; Imoniana, J.O.; Benetti, C.; Slomski, V.G.; Slomski, V. Relationships Between Corporate Control Environment and Stakeholders That Mediate Pressure on Independent Auditors in France. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060311

Carhuapomachacon G, Imoniana JO, Benetti C, Slomski VG, Slomski V. Relationships Between Corporate Control Environment and Stakeholders That Mediate Pressure on Independent Auditors in France. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(6):311. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060311

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarhuapomachacon, Giemegerman, Joshua Onome Imoniana, Cristiane Benetti, Vilma Geni Slomski, and Valmor Slomski. 2025. "Relationships Between Corporate Control Environment and Stakeholders That Mediate Pressure on Independent Auditors in France" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 6: 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060311

APA StyleCarhuapomachacon, G., Imoniana, J. O., Benetti, C., Slomski, V. G., & Slomski, V. (2025). Relationships Between Corporate Control Environment and Stakeholders That Mediate Pressure on Independent Auditors in France. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(6), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060311