Exporting Under Political Risk: Payment Term Selection in Global Trade

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Related Literature and Contributions

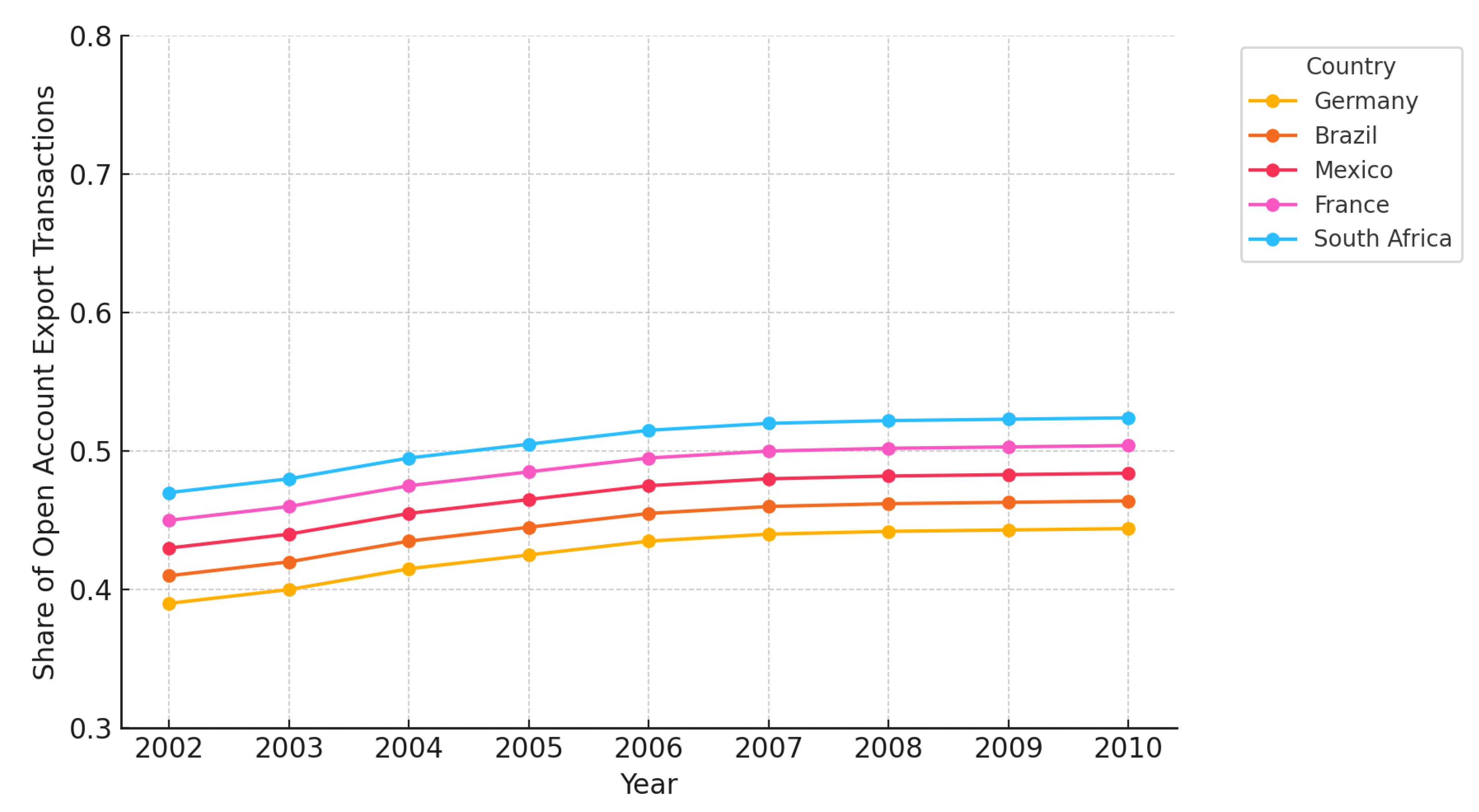

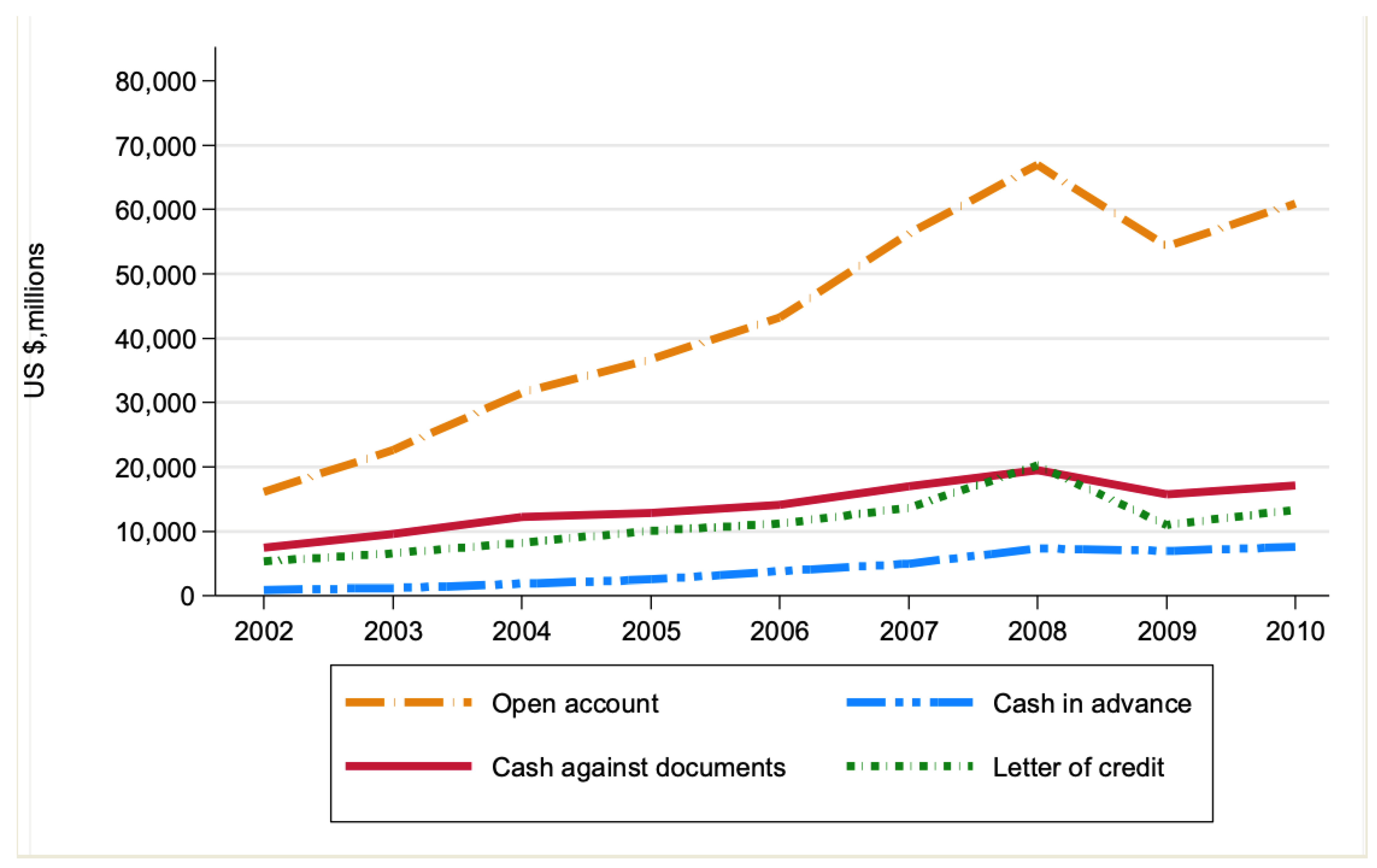

3. Data

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Benchmark Case

4.2. Robustness Checks

4.3. The Role of Industry Complexity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| D_Mena | Drop Mena Countries |

| D_African | Drop African Countries |

| D_Asian | Drop Asian Countries |

| D_European | Drop European Countries |

| D_LowInc | Drop Low-Income Countries |

| D_LMInc | Drop Lower-to-Middle-Income Countries |

| D_UMInc | Drop Upper-Middle-Income Countries |

| D_HighInc | Drop High-Income Countries |

| D_Textile&Basic Materials & Machinery and Equipment | Drop Textile & Basic Materials & Machinery and Equipment |

| LO | Law and Order |

| DA | Democratic Accountability |

| BQ | Bureaucratic Quality |

| MP | Military in Politics |

| EC | External Conflict |

| IP | Investment Profile |

| SC | Socioeconomic Condition |

| GS | Government Stability |

| IC | Internal Conflict |

Appendix A

| Component | Explained Variance (%) | Cumulative Variance (%) | Top Contributing Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 61.3 | 61.3 | Law and Order, Bureaucratic Quality, Investment Profile |

| PC2 | 21.7 | 83.0 | Democratic Accountability, Internal Conflict, External Conflict |

| Model | R-Squared/ Pseudo R2 | F-Stat/Chi2 | VIF Range | Breusch-Pagan (p-Value) | Wooldridge Test (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | 0.32 | 52.8 | 1.1–2.8 | 0.21 | 0.35 |

| Probit | 0.27 | 45.3 | 1.0–2.6 | nan | nan |

| Ordered Logit | 0.29 | 49.1 | 1.2–2.9 | nan | nan |

| Political Risk Indicator | Main Effect (β) | Interaction with Complexity (β) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Law and Order | 0.009 | 0.012 | *** |

| Democratic Accountability | 0.011 | 0.006 | ** |

| Bureaucratic Quality | 0.013 | 0.014 | *** |

| Military in Politics | 0.013 | 0.016 | *** |

| External Conflict | 0.018 | 0.01 | ** |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Account Exports | 24,886 | 0.532 | 0.422 | 0 | 1 |

| Law and Order | 24,886 | 3.729 | 1.325 | 0.5 | 6 |

| Democratic Accountability | 24,886 | 4.034 | 1.735 | 0 | 6 |

| Bureaucratic Quality | 24,886 | 2.193 | 1.116 | 0 | 4 |

| Military in Politics | 24,886 | 3.863 | 1.692 | 0 | 6 |

| External Conflict | 24,886 | 9.922 | 1.459 | 2.125 | 12 |

| Investment Profile | 24,886 | 8.819 | 2.464 | 1 | 12 |

| Socioeconomic Conditions | 24,886 | 5.777 | 2.622 | 0 | 11 |

| Internal Conflict | 24,886 | 9.399 | 1.660 | 2.917 | 12 |

| Government Stability | 24,886 | 8.535 | 1.539 | 3.167 | 11.5 |

| 1 | We discuss these in more detail in the next section of the paper. |

| 2 | Turkcan and Avsar (2018), Avsar (2020), and Demir and Javorcik (2018) are the only exceptions in this regard. |

| 3 | Total exports to Middle Eastern countries were recorded to be about USD 3 billion in 2002 and more than USD 23 billion in 2010. This increase represents the largest regional jump over those years in Turkish exports. |

| 4 | Following Antras and Foley (2015), we classified open accounts and documentary collection as post-shipment terms. |

| 5 | Antras and Foley (2015) obtained a similar estimation using multinomial logit. |

References

- Ahn, J., & Sarmiento, M. (2013). Estimating the direct impact of bank liquidity shocks on the real economy: Evidence from letter-of-credit import transactions in Colombia. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Amiti, M., & Weinstein, D. E. (2011). Exports and financial shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 1841–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. E., & Marcouiller, D. (2002). Insecurity and the pattern of trade: An empirical investigation. Review of Economics and statistics, 84(2), 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antras, P., & Foley, C. F. (2015). Poultry in motion: A study of international trade finance practices. Journal of Political Economy, 123(4), 853–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auboin, M. (2007). Boosting trade finance in developing countries: What link with the WTO?, WTO staff working paper ERSD no. 2007-04. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd200704_e.htm (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Auboin, M., & Engemann, M. (2014). Testing the trade credit and trade link: Evidence from data on export credit insurance. Review of World Economics, 150(4), 715–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsar, V. (2020). Travel visas and trade finance. Economics Bulletin, 40(1), 567–573. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T. (2003). Financial dependence and international trade. Review of International Economics, 11(2), 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, D., Moenius, J., & Pistor, K. (2006). Trade, law, and product complexity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(2), 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, M. H., Gozgor, G., & Lau, C. K. M. (2017). Institutions and gravity model: The role of political economy and corporate governance. Eurasian Business Review, 7, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, V., & Nistico, R. (2014). Military in politics and budgetary allocations. Journal of Comparative Economics, 42(4), 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, M., & Hefeker, C. (2007). Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauffour, J. P., & Farole, T. (2009). Trade finance in crisis: Market adjustment or market failure. Effective crisis response and openness: Implication for the trading system (pp. 119–142). The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Chor, D., & Manova, K. (2012). Off the cliff and back? Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis. Journal of International Economics, 87(1), 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B., & Javorcik, B. (2018). Don’t throw in the towel, throw in trade credit! Journal of International Economics, 111, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glady, N., & Potin, J. (2011). Bank intermediation and default risk in international trade-theory and evidence. ESSEC Business School, Mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- Gur, N., & Avşar, V. (2016). Financial system, R&D intensity and comparative advantage. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 25(2), 213–239. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, P. (2002). Political risk and equity investment in developing countries. Applied Economics Letters, 9(6), 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, P., & Ursprung, H. W. (2002). Do civil and political repression really boost foreign direct investments? Economic Inquiry, 40(4), 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefele, A., Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T., & Yu, Z. (2016). Payment choice in international trade: Theory and evidence from cross-country firm-level data. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne D’économique, 49(1), 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, L. D. (2011). International country risk guide methodology (p. 7). PRS Group. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, J., Raj, M., & Riyanto, Y. E. (2006). Finance and trade: A cross-country empirical analysis on the impact of financial development and asset tangibility on international trade. World Development, 34(10), 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensink, R., Hermes, N., & Murinde, V. (2000). Capital flight and political risk. Journal of international Money and Finance, 19(1), 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A. G. (2008). Bilateral trade in the shadow of armed conflict. International Studies Quarterly, 52(1), 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, I. (2013). Role of Trade Finance. In The evidence and impact of financial globalization (pp. 199–212). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manova, K. (2008). Credit constraints, equity market liberalizations and international trade. Journal of International Economics, 76(1), 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manova, K., Wei, S. J., & Zhang, Z. (2015). Firm exports and multinational activity under credit constraints. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(3), 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, A. M. C. (2009). Inter-firm trade finance in times of crisis (p. 5112). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, J. D., Siverson, R. M., & Tabares, T. E. (1998). The political determinants of international trade: The major powers, 1907–1990. American Political Science Review, 92(3), 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C., Nestmann, T., & Wedow, M. (2008). Political risk and export promotion: Evidence from Germany. World Economy, 31(6), 781–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niepmann, F., & Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T. (2017). International trade, risk and the role of banks. Journal of International Economics, 107, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, N. (2007). Relationship-specificity, incomplete contracts, and the pattern of trade. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 569–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C. H., & Reuveny, R. (2010). Climatic natural disasters, political risk, and international trade. Global Environmental Change, 20(2), 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M. (2013). How firms overcome weak international contract enforcement: Repeated interaction, collective punishment and trade finance. University of Navarra, IESE Business School, Mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T. (2013). Towards a theory of trade finance. Journal of International Economics, 91(1), 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, B., & Ruiz, I. (2012). Political risk, macroeconomic uncertainty, and the patterns of foreign direct investment. The International Trade Journal, 26(2), 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkcan, K., & Avsar, V. (2018). Financial dependence and the terms of payments in international transactions. Applied Economics Letters, 25(8), 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Veer, K. J. (2015). The private export credit insurance effect on trade. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 82(3), 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Open Account | Letter of Credit | Cash in Advance | Cash Against Documents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 52.1 | 17.3 | 3.1 | 24.1 |

| 2003 | 54.5 | 15.9 | 2.9 | 23.0 |

| 2004 | 56.5 | 14.7 | 3.4 | 21.9 |

| 2005 | 57.5 | 15.7 | 3.9 | 20.0 |

| 2006 | 59.2 | 14.9 | 5.1 | 18.8 |

| 2007 | 56.9 | 17.4 | 5.2 | 17.9 |

| 2008 | 60.1 | 17.2 | 6.2 | 15.6 |

| 2009 | 60.4 | 12.1 | 7.7 | 15.4 |

| 2010 | 61.2 | 13.2 | 7.5 | 15.9 |

| Overall | 57.6 | 15.3 | 5.0 | 19.1 |

| Open Account | Letter of Credit | Cash in Advance | Cash Against Documents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 63.8 | 7.5 | 4.1 | 14.9 |

| Middle East | 34.7 | 35.2 | 8.1 | 19.6 |

| North America | 48.2 | 23.3 | 5.8 | 16.1 |

| Asia | 32.42 | 35.6 | 8.8 | 16.1 |

| Africa | 38.6 | 33.2 | 7.6 | 21.2 |

| Industries | Overall | Exports to Countries Above Median Law-and-Order Level |

|---|---|---|

| Food products and beverages | 0.623 | 0.639 |

| Tobacco products | 0.156 | 0.167 |

| Textiles | 0.660 | 0.691 |

| Manufacture of wearing apparel; dressing and dyeing of fur | 0.655 | 0.685 |

| Leather products | 0.530 | 0.579 |

| Wood products | 0.479 | 0.420 |

| Paper products | 0.546 | 0.605 |

| Publishing and printing | 0.507 | 0.523 |

| Petroleum products | 0.528 | 0.506 |

| Chemicals | 0.647 | 0.688 |

| Rubber and plastics | 0.664 | 0.717 |

| Non-metallic mineral products | 0.620 | 0.643 |

| Basic metals | 0.410 | 0.441 |

| Manufacture of fabricated metal products | 0.565 | 0.636 |

| Manufacture of machinery and equipment | 0.627 | 0.611 |

| Manufacture of office, accounting, and computing machinery | 0.374 | 0.387 |

| Manufacture of electrical machinery and apparatus | 0.643 | 0.649 |

| Manufacture of radio, television, and communication equipment | 0.437 | 0.464 |

| Manufacture of medical, precision, and optical instruments, including watches | 0.506 | 0.486 |

| Manufacture of motor vehicles, trailers, and semi-trailers | 0.586 | 0.627 |

| Manufacture of other transport equipment | 0.327 | 0.381 |

| Manufacture of furniture | 0.615 | 0.730 |

| Law and Order | Democratic Accountability | Bureaucratic Quality | Military in Politics | External Conflict | Investment Profile | Socioeconomic Conditions | Government Stability | Internal Conflict | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LO | 1.000 | ||||||||

| DA | 0.3034 *** | 1.000 | |||||||

| BQ | 0.6250 *** | 0.5482 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| MP | 0.6180 * | 0.5344 ** | 0.6987 * | 1.000 | |||||

| EC | 0.2371 * | 0.2675 | 0.3459 ** | 0.4581 * | 1.000 | ||||

| IP | 0.6165 *** | 0.4939 *** | 0.6886 *** | 0.6950 * | 0.4368 * | 1.000 | |||

| SC | 0.7437 *** | 0.3488 ** | 0.7745 ** | 0.6915 ** | 0.3248 ** | 0.7397 * | 1.000 | ||

| GS | 0.1771 * | 0.3625 ** | 0.0393 *** | 0.0023 | 0.1626 * | 0.1206 ** | 0.1848 * | 1.000 | |

| IC | 0.5884 *** | 0.3086 *** | 0.4736 ** | 0.6447 ** | 0.5465 *** | 0.5557 *** | 0.5818 *** | 0.2319 * | 1.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LO | 0.014 *** | ||||||||

| (0.002) | |||||||||

| DA | 0.016 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| BQ | 0.018 *** | ||||||||

| (0.002) | |||||||||

| MP | 0.019 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| EC | 0.020 *** | ||||||||

| (0.002) | |||||||||

| IP | 0.008 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| SC | 0.004 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| GS | 0.003 ** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| IC | 0.016 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| Control Variables | |||||||||

| Log (Exports)it−1 | 0.037 *** | 0.035 *** | 0.036 *** | 0.035 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.036 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.039 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Net Interest Margin | 0.007 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.008 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| N | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LO | 0.112 *** | ||||||||

| (0.020) | |||||||||

| DA | 0.022 * | ||||||||

| (0.013) | |||||||||

| BQ | 0.103 *** | ||||||||

| (0.024) | |||||||||

| MP | 0.040 *** | ||||||||

| (0.015) | |||||||||

| EC | 0.035 ** | ||||||||

| (0.016) | |||||||||

| IP | 0.032 *** | ||||||||

| (0.012) | |||||||||

| SC | 0.027 ** | ||||||||

| (0.011) | |||||||||

| GS | 0.010 *** | ||||||||

| (0.004) | |||||||||

| IC | 0.005 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| Control Variables | |||||||||

| Log (Exports)it−1 | 1.327 *** | 1.333 *** | 1.322 *** | 1.330 *** | 1.337 *** | 1.326 *** | 1.327 *** | 1.336 *** | 1.336 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| Net Interest Margin | 0.019 ** | 0.000 | 0.016 * | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| N | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 |

| LO (1) | DA (2) | BQ (3) | MP (4) | EC (5) | IP (6) | SC (7) | GS (8) | IC (9) | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D_MENA | 0.011 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.003 | 0.014 *** | 21,873 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| D_African | 0.018 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.020 *** | 19,412 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| D_Asian | 0.007 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.003 ** | 0.005 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.004 *** | 18,699 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| D_European | 0.007 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.003 ** | 0.002 *** | 0.001 | 0.010 *** | 19,573 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| D_LowInc | 0.012 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.017 *** | 21,137 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| D_LMInc | 0.008 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.012 *** | 19,711 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| D_UMInc | 0.021 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.021 *** | 18,860 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| D_HighInc | 0.017 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.014 | 16,054 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| D_Textile & Basic Materials & Machinery and Equipment | 0.014 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.001 | 0.014 *** | 21,640 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LO | 0.110 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| DA | 0.061 *** | ||||||||

| (0.006) | |||||||||

| BQ | 0.122 *** | ||||||||

| (0.011) | |||||||||

| MP | 0.007 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| EC | 0.021 *** | ||||||||

| (0.002) | |||||||||

| IP | 0.061 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| SC | 0.059 *** | ||||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||||

| GS | 0.014 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| IC | 0.042 ** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| Control Variables | |||||||||

| Log (Exports)it−1 | 0.152 *** | 0.150 *** | 0.138 *** | 0.150 *** | 0.158 *** | 0.146 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.158 *** | 0.157 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Net Interest Margin | 0.022 *** | 0.030 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.031 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.034 *** | 0.029 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| N | 23,804 | 23,804 | 23,804 | 23,804 | 23,804 | 23,804 | 23,804 | 23,804 | 23,804 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal Effects for Pre-Shipment | Marginal Effects for Bank Intermediation | Marginal Effects for Post-Shipment | |

| Law and Order | −0.004 *** | −0.005 *** | 0.009 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Democratic Accountability | −0.005 *** | −0.008 *** | 0.014 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| Bureaucratic Quality | −0.004 *** | −0.007 *** | 0.012 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| Military in Politics | −0.006 *** | −0.009 *** | 0.015 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| External Conflict | −0.002 *** | −0.004 *** | 0.007 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| Investment Profile | −0.002 *** | −0.004 *** | 0.006 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Socioeconomic Conditions | −0.001 *** | −0.002 *** | 0.003 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| Government Stability | −0.002 *** | −0.003 *** | 0.006 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| Internal Conflict | −0.004 *** | −0.007 *** | 0.012 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| N | 24,886 | 24,886 | 24,886 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Law and Order | 0.009 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| LO × Complexity | 0.012 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| Democratic Accountability | 0.011 *** | ||||||||

| (0.003) | |||||||||

| DA × Complexity | 0.006 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| Bureaucratic Quality | 0.013 *** | ||||||||

| (0.004) | |||||||||

| BQ × Complexity | 0.014 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| Military in Politics | 0.013 *** | ||||||||

| (0.003) | |||||||||

| MP × Complexity | 0.016 *** | ||||||||

| (0.005) | |||||||||

| External Conflict | 0.018 *** | ||||||||

| (0.003) | |||||||||

| EC × Complexity | 0.010 *** | ||||||||

| (0.006) | |||||||||

| Investment Profile | 0.006 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| IP × Complexity | 0.004 ** | ||||||||

| (0.002) | |||||||||

| SC | 0.003 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| SC × Complexity | 0.003 *** | ||||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||||

| Government Stability | 0.002 *** | ||||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||||

| GS × Complexity | 0.001 | ||||||||

| (0.006) | |||||||||

| Internal Conflict | 0.012 *** | ||||||||

| (0.003) | |||||||||

| IC × Complexity | 0.001 *** | ||||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||||

| N |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avsar, V.; Batmaz, O. Exporting Under Political Risk: Payment Term Selection in Global Trade. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060298

Avsar V, Batmaz O. Exporting Under Political Risk: Payment Term Selection in Global Trade. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(6):298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060298

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvsar, Veysel, and Oguzhan Batmaz. 2025. "Exporting Under Political Risk: Payment Term Selection in Global Trade" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 6: 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060298

APA StyleAvsar, V., & Batmaz, O. (2025). Exporting Under Political Risk: Payment Term Selection in Global Trade. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(6), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060298