Does Information Asymmetry Affect Firm Disclosure? Evidence from Mergers and Acquisitions of Financial Institutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

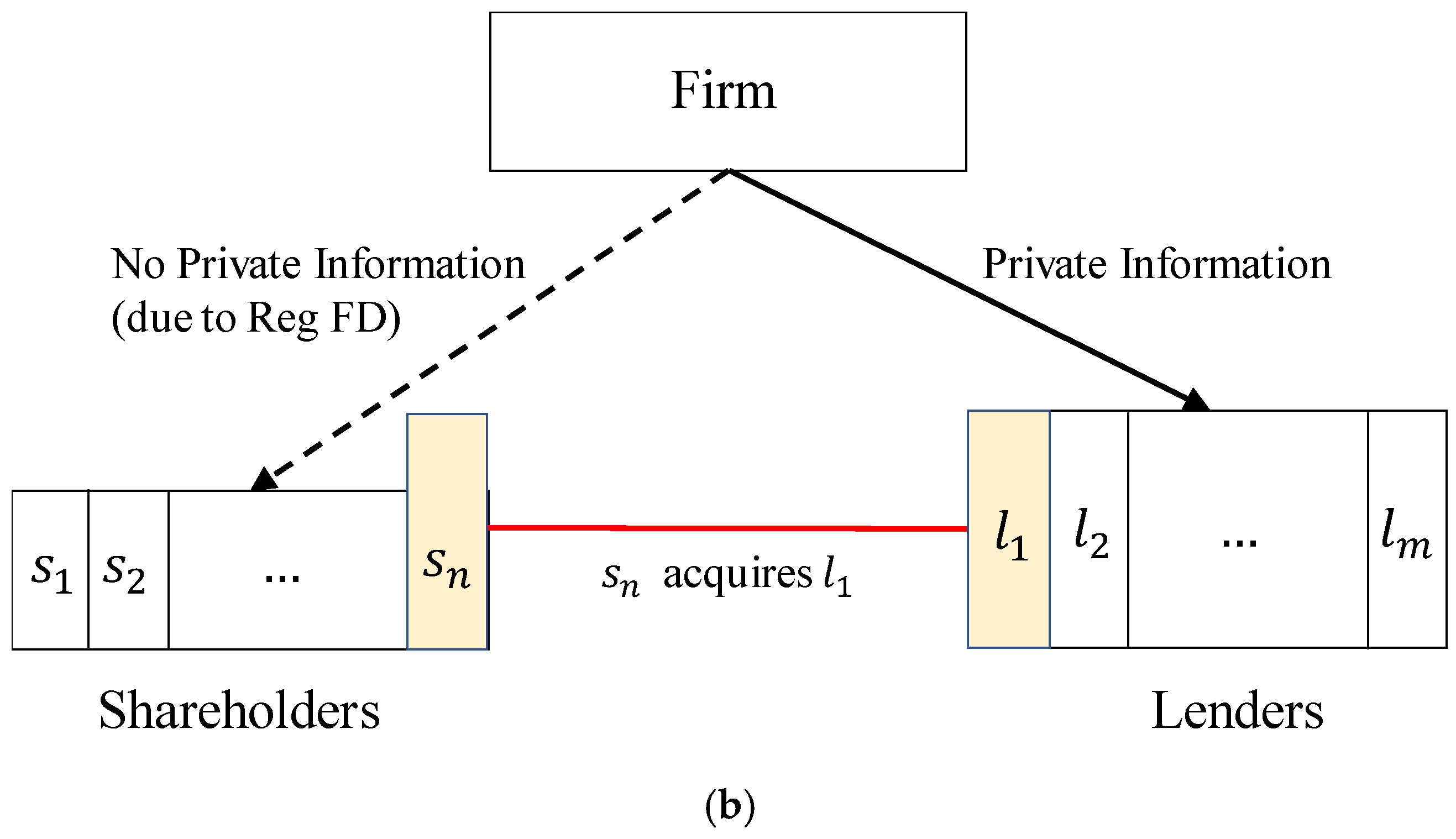

2.1. Information Flows from Lenders to Shareholders

2.2. Information Asymmetry and Voluntary Disclosure

3. Research Design

3.1. Information Asymmetry and Shareholder–Lender Merger Transactions

3.2. Disclosure and Shareholder–Lender Merger Transactions

4. Empirical Analyses

4.1. Sample and Descriptive Statistics

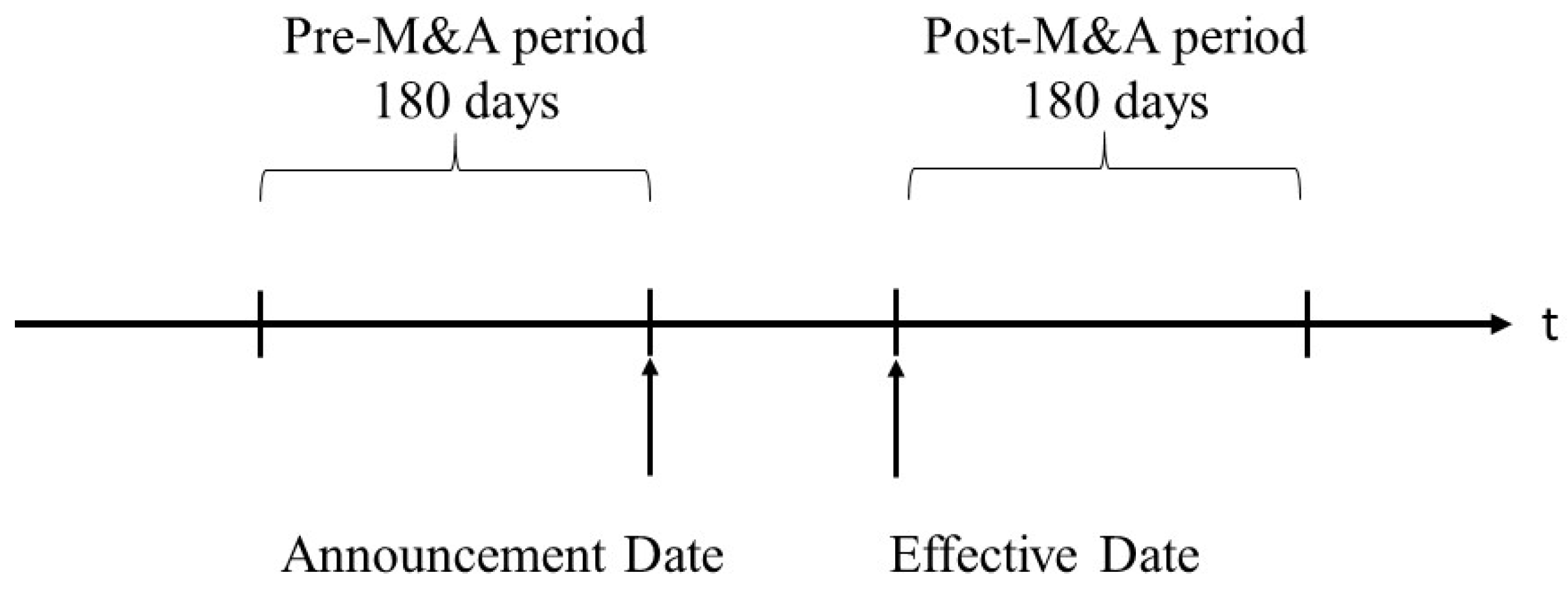

4.2. Information Asymmetry and Shareholder–Lender Merger Transactions (H1)

4.3. Disclosure and Shareholder–Lender Merger Transactions (H2)

5. Robustness Analyses

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Variable Definitions

| Variables | Definition |

| Spread | The daily bid–ask spreads averaged over a 180-day window, multiplied by 100. A daily bid–ask spread is calculated as the closing bid–ask spread from CRSP scaled by the mid-point of bid and ask prices. Spread = 100 * (ask − bid)/[(ask + bid)/2]. |

| AIM | Amihud’s (2002) illiquidity measure, averaged over a 180-day window. The daily AIM is calculated from CRSP as follows: AIM = log (1 + 10,000,000 × abs (ret)/(prc × vol)). |

| Frequency | The natural logarithm of one plus the number of quarterly management forecasts (including earnings, sales, capital expenditure, EBITDA, and gross margin) issued in a 180-day window. |

| Precision | The precision of a quarterly management earnings forecast, measured as the negative of the forecast width (the magnitude of the range for range forecasts and zero for point forecasts), scaled by the beginning-of-quarter stock price and multiplied by 100. |

| Post | An indicator variable equal to one for observations after the shareholder–lender merger transactions, and zero otherwise. |

| Treat | An indicator variable equal to one for treatment firms, and zero otherwise. |

| LnSize | The natural logarithm of the market value of equity, measured at the fiscal year-end preceding the announcement of the shareholder–lender merger transactions. |

| LnNumAF | The natural logarithm of one plus the number of analysts covering a firm during a 365-day window preceding the announcement of the shareholder–lender merger transactions. |

| ROA | Return on assets, income before extraordinary income divided by lagged total assets, measured at the fiscal year-end preceding the announcement of the shareholder–lender merger transactions. |

| MTB | Market-to-book ratio, the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity, measured at the fiscal year-end preceding the announcement of the shareholder–lender merger transactions. |

| LnPRC | Natural logarithm of stock price at the fiscal quarter-end preceding the announcement of the shareholder–lender merger transactions. |

| PerctInst | Percentage of firms’ shares owned by institutional investors, measured at the fiscal quarter-end immediately preceding the announcement of the shareholder–lender merger transactions. |

| Point | An indicator variable equal to one if a management earnings forecast is a point estimate, and zero otherwise. |

| Loss | An indicator variable equal to one if a management earnings forecast is negative, and zero otherwise. |

| LnHorizon | The natural logarithm of one plus the number of days between the management earnings forecast date and the end of the fiscal period to which the management forecast applies. |

| 1 | Two types of information asymmetry discussed in the literature are information asymmetry among equity investors and information asymmetry between firm managers and investors. Section 2 discusses these two types of information asymmetry in more detail. In this study, we focus on the information asymmetry among equity investors. |

| 2 | Disclosure can also reduce information asymmetry between managers and investors (e.g., M. H. Lang & Lundholm, 2000; Botosan, 2000; Healy & Palepu, 2001; Beyer et al., 2010). |

| 3 | The timing of the required public disclosure depends on whether the selective disclosure was intentional or non-intentional. For an intentional disclosure, the issuer must make public disclosure simultaneously; for a non-intentional disclosure, the issuer must make public disclosure within 24 h. |

| 4 | Regulation FD prohibits any selective disclosure of material information by a firm to its shareholders, but Regulation FD does not apply to loan lenders. Rule 100(b)(2) of Regulation FD outlines four coverage exclusions of the regulation. |

| 5 | The merger between a shareholder and a lender of the same firm represents an exogenous shock to information asymmetry because it is not related to the firm’s operation and performance. As we cannot rule out the possibility that the merger transaction is completed mainly for the equity holder to gain firm-specific private information from the lender, the shock on information asymmetry is termed quasi-exogenous. |

| 6 | Prior literature finds that information asymmetry between managers and investors also negatively affects market liquidity and cost of equity (e.g., Myers & Majluf, 1984; Merton, 1987; M. Lang & Lundholm, 1993; Healy & Palepu, 1995; Botosan, 2000; Healy & Palepu, 2001; Beyer et al., 2010). Note that the shareholder–lender merger leads to a decrease, rather than an increase, in the level of information asymmetry between managers and investors, because the acquiring shareholder gains access to firm-specific private information after the merger. The decrease in information asymmetry between managers and investors is unlikely to prompt firms to increase disclosure and improve disclosure quality. |

| 7 | Statistical rating organizations and credit rating agencies were originally exempt from Regulation FD. |

| 8 | Previous studies provide substantial evidence that hedge funds obtain and utilize private information (e.g., Yang et al., 2021; B. Chen et al., 2025). |

| 9 | We acknowledge it is possible that mergers between a shareholder and a lender of the same firm affect disclosure in an indirect way. These mergers could increase the information asymmetry perceived by other shareholders observing the merger transactions, and prompt them to demand a larger risk premium as compensation for the perceived increase in risk associated with the perceived increase in information asymmetry (e.g., Copeland & Galai, 1983; Glosten & Milgrom, 1985; Kyle, 1985). Firms might then respond by increasing disclosure and improving disclosure quality to mitigate these negative effects. |

| 10 | Kelly and Ljungqvist (2012) find evidence that the closures and mergers of brokerage houses’ research operations represent a plausibly exogenous shock to information asymmetry and use this setting to show that information asymmetry is priced. While a brokerage closure can increase the information asymmetry among investors, it can also increase the information asymmetry between managers and investors. |

| 11 | There are two reasons for using a 180-day window both before and after shareholder–lender merger transactions. First, we use quarterly forecasts (including earnings, sales, capital expenditures, EBITDA, and gross margin) as proxies for disclosure. Second, it takes time for the effects of shareholder–lender mergers to manifest and for managers to adjust their disclosure practices. |

| 12 | There are many firm-specific factors that affect a firm’s bid–ask spread and AIM (such as new product releases or media coverage). Therefore, we use multiple control observations for each treatment observation to mitigate the impact of idiosyncratic factors in the analysis. |

| 13 | Each shareholder–lender merger transaction is associated with multiple treatment observations. For example, suppose financial institution A is a shareholder of firms C1 and C2, and financial institution B is a lender of firms C1 and C2, then the merger of A and B leads to two treatment observations (C1 and C2). |

| 14 | In 2001, the stock exchanges (NYSE, AMEX, and NASDAQ) completed a process of decimalization, changing security price quotes from a minimum price movement of USD 0.0625 (1/16th of a dollar) to decimals with a minimum price movement of USD 0.01; Sarbanes–Oxley was enacted in 2002; the Global Analyst Research Settlement was completed in 2003; and the 8-K regulation went to effect in 2004. |

| 15 | Specifically, MiFID II came into effect in January 2018 and Regulatory Notice 18−08 was issued in February 2018. Although MiFID II primarily applies to firms operating within the European Union (EU), US firms that have EU clients or engage in transactions involving EU financial instruments may be subject to MiFID II requirements. Regulatory Notice 18−08 reminds firms of their obligations under FINRA rules to prevent the misuse of nonpublic information and to ensure effective supervision and control of insider trading risks. |

References

- Addoum, J., & Murfin, J. R. (2020). Equity price discovery with informed private debt. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(8), 3766–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P., & O’Hara, M. (2007). Information risk and capital structure (Working paper). Cornell University. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, K., & Sosyura, D. (2014). Who writes the news? Corporate press releases during merger negotiations. The Journal of Finance, 69(1), 241–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akins, B. K., Ng, J., & Verdi, R. S. (2012). Investor competition over information and the pricing of information asymmetry. Accounting Review, 87(1), 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A., & Meeks, G. (2019). Bidder earnings forecasts in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Corporate Finance, 58, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amihud, Y. (2002). Illiquidity and stock returns: Cross-section and time-series effects. Journal of Financial Markets, 5(1), 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amihud, Y., & Mendelson, H. (1986). Asset pricing and the bid-ask spread. Journal of Financial Economics, 17(2), 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. (2006, October 16). Hedge funds draw insider scrutiny. The New York Times. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, C. S., Core, J. E., Taylor, D. J., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2011). When does information asymmetry affect the cost of capital? Journal of Accounting Research, 49(1), 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badertscher, B. A. (2011). Overvaluation and the choice of alternative earnings management mechanisms. The Accounting Review, 86(5), 1491–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K., Billings, M., Kelly, B., & Ljungqvist, A. (2014). Shaping liquidity: On the causal effects of voluntary disclosure. Journal of Finance, 69, 2237–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, A., Cohen, D. A., Lys, T. Z., & Walther, B. R. (2010). The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 296–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, N., Ecker, F., Olsson, P. M., & Schipper, K. (2012). Direct and mediated associations among earnings quality, information asymmetry, and the cost of equity. Accounting Review, 87(2), 449–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojraj, S., Cho, Y. J., & Yehuda, N. I. R. (2012). Mutual fund family size and mutual fund performance: The role of regulatory changes. Journal of Accounting Research, 50(3), 647–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, M. E., & Keim, D. B. (2012). Institutional investors and stock market liquidity: Trends and relationships (Working paper). University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Botosan, C. A. (1997). Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review, 72(3), 323–349. [Google Scholar]

- Botosan, C. A. (2000). Evidence that greater disclosure lowers the cost of equity capital. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 12(4), 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C. A., & Plumlee, M. A. (2002). A Re-examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M. J., & Subrahmanyam, A. (1996). Market microstructure and asset pricing: On the compensation for illiquidity in stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 41(3), 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L. D., Call, A. C., Clement, M. B., & Sharp, N. Y. (2015). Inside the “Black Box” of sell-side financial analysts. Journal of Accounting Research, 53(1), 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S., & Hillegeist, S. A. (2007). How disclosure quality affects the level of information asymmetry. Review of Accounting Studies, 12(2), 443–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S., Hillegeist, S. A., & Lo, K. (2004). Conference calls and information asymmetry. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 37(3), 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushee, B. J., Core, J. E., Guay, W., & Hamm, S. J. W. (2010). The role of the business press as an information intermediary. Journal of Accounting Research, 48(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushee, B. J., Matsumoto, D. A., & Miller, G. S. (2004). Managerial and investor responses to disclosure regulation: The case of reg FD and conference calls. The Accounting Review, 79(3), 617–643. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman, R. M., Smith, A. J., & Wittenberg-Moerman. (2010). Price discovery and dissemination of private information by loan syndicate participants. Journal of Accounting Research, 48(5), 921–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Kazemi, M. M., & Yang, X. (2025). Do hedge fund clients of prime brokers front-run their analysts? International Review of Economics & Finance, 97, 103824. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q., & Vashishtha, R. (2017). The effects of bank mergers on corporate information disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 64(1), 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., & Martin, X. (2011). Do bank-affiliated analysts benefit from lending relationships? Journal of Accounting Research, 49(3), 633–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q., Luo, T., & Yue, H. (2013). Managerial incentives and management forecast precision. The Accounting Review, 88(5), 1575–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiyachantana, C. N., Jiang, C. X., Taechapiroontong, N., & Wood, R. A. (2004). The impact of regulation fair disclosure on information asymmetry and trading: An intraday analysis. Financial Review, 39(4), 549–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y. (2017). Shareholder-creditor conflict and payout policy: Evidence from mergers between lenders and shareholders (Working paper). University of South Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, D. C., Kalpathy, S., & Sulaeman, J. (2011). Equity analysts affiliated with corporate lenders (Working paper). University of Tennessee, Southern Methodist University. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D. A. (2003). Quality of financial reporting choice: Determinants and economic consequences (Working paper). University of Texas at Dallas. [Google Scholar]

- Coller, M., & Yohn, T. L. (1997). Management forecasts and information asymmetry: An examination of bid-ask spreads. Journal of Accounting Research, 35(2), 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, T. E., & Galai, D. (1983). Information effects on the bid-ask spread. The Journal of Finance, 38(5), 1457–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Cotter, J., Tuna, I., & Wysocki, P. D. (2006). Expectations management and beatable targets: How do analysts react to explicit earnings guidance? Contemporary Accounting Research, 23(3), 593–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, S. A., & Mullineaux, D. J. (2000). Syndicated loans. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 9(4), 404–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. W. (1984). Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. The Review of Economic Studies, 51(3), 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. W. (1985). Optimal release of information by firms. The Journal of Finance, 40(4), 1071–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. W., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1991). Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance, 46(4), 1325–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierkens, N. (1991). Information asymmetry and equity issues. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 26(2), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, P., & Paudyal, K. (2008). Information asymmetry and bidders’ gains. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 35(3–4), 376–405. [Google Scholar]

- Easley, D., Hvidkjaer, S., & O’Hara, M. (2002). Is information risk a determinant of asset returns? The Journal of Finance, 57(5), 2185–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, D., & O’Hara, M. (2004). Information and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance, 59(4), 1553–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M., Wang, S. W., & Zhang, X. F. (2012). The change in information uncertainty and acquirer wealth losses. Review of Accounting Studies, 17, 913–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F. (1985). What’s different about banks? Journal of Monetary Economics, 15(1), 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The cross-section of expected stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427–465. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43(2), 153–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R., Kraft, A., & Zhang, H. (2012). Financial reporting frequency, information asymmetry, and the cost of equity. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 54(2), 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R., & Lennox, C. (2011). Do acquirers disclose good news or withhold bad news when they finance their acquisitions using equity? Review of Accounting Studies, 16(1), 183–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosten, L. R., & Milgrom, P. R. (1985). Bid, ask and transaction prices in a specialist market with heterogeneously informed traders. Journal of Financial Economics, 14(1), 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P. A., & Metrick, A. (2001). Institutional investors and equity prices. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, T. H., Neamtiu, M., Shroff, N., & White, H. D. (2014). Management forecast quality and capital investment decisions. The Accounting Review, 89(1), 331–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., & Rajgopal, S. (2005). The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40(1), 3–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, M. M., & Sami, H. (1994). The impact of the SEC’s segment disclosure requirement on bid-ask spreads. The Accounting Review, 69(1), 179–199. [Google Scholar]

- He, J., & Huang, J. (2017). Product market competition in a world of cross-ownership: Evidence from institutional blockholdings. The Review of Financial Studies, 30(8), 2674–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P. M., Hutton, A. P., & Palepu, K. G. (1999). Stock performance and intermediation changes surrounding sustained increases in disclosure. Contemporary Accounting Research, 16(3), 485–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (1995). The challenges of investor communication the case of CUC International, Inc. Journal of Financial Economics, 38(2), 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31(1–3), 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heflin, F. L., Shaw, K. W., & Wild, J. J. (2005). Disclosure policy and market liquidity: Impact of depth quotes and order sizes. Contemporary Accounting Research, 22(4), 829–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, D. E., Koonce, L., & Venkataraman, S. (2008). Management earnings forecasts: A review and framework. Accounting Horizons, 22(3), 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H., & Kacperczyk, M. (2010). Competition and bias. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(4), 1683–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. (2013). Shareholder coordination, corporate governance, and firm value (Working paper). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. (2016). Shareholder coordination and the market for corporate control (Working paper). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J. S., Liu, J., & Liu, J. (2007). Information asymmetry, diversification, and cost of capital. The Accounting Review, 82(3), 705–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, A. P., Miller, G. S., & Skinner, D. J. (2003). The role of supplementary statements with management earnings forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research, 41(5), 867–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashina, V., & Sun, Z. (2011). Institutional stock trading on loan market information. Journal of Financial Economics, 100(2), 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M. (2020). Resolving information asymmetry through contractual risk sharing: The case of private firm acquisitions. Journal of Accounting Research, 58(5), 1203–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W., Li, K., & Shao, P. (2010). When shareholders are creditors: Effects of the simultaneous holding of equity and debt by non-commercial banking institutions. The Review of Financial Studies, 23(10), 3595–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, B., Petroni, K. R., & Yu, Y. (2008). The effect of regulation fd on transient institutional investors’ trading behavior. Journal of Accounting Research, 46(4), 853–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B., & Ljungqvist, A. (2012). Testing asymmetric-information asset pricing models. Review of Financial Studies 25, 1366–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A. S., Lefanowicz, C. E., & Robinson, J. R. (2013). Regulation FD: A review and synthesis of the academic literature. Accounting Horizons, 27(3), 619–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Mullally, K., Ray, S., & Tang, Y. (2020). Prime (information) brokerage. Journal of Financial Economics. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, A. S. (1985). Continuous auctions and insider trading. Econometrica, 53(6), 1315–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R. A., Leuz, C., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2012). Information asymmetry, information precision, and the cost of capital. Review of Finance, 16(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M., & Lundholm, R. (1993). Cross-sectional determinants of analyst ratings of corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 31(2), 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M. H., & Lundholm, R. J. (2000). Voluntary disclosure and equity offerings: Reducing information asymmetry or hyping the stock? Contemporary Accounting Research, 17(4), 623–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, C., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2000). The economic consequences of increased disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, 38, 91–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, C., & Wysocki, P. (2016). The economics of disclosure and financial reporting regulation: Evidence and suggestions for future research. Journal of Accounting Research 54, 525–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, B. (1988). Toward a theory of equitable and efficient accounting policy. The Accounting Review, 63(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lewellen, K., & Lowry, M. (2021). Does common ownership really increase firm coordination? Journal of Financial Economics, 141(1), 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Zhang, L. (2015). Short selling pressure, stock price behavior, and management forecast precision: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Accounting Research, 53(1), 79–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, M., & Rehman, Z. (2008). Information flows within financial conglomerates: Evidence from the banks–mutual funds relation. Journal of Financial Economics, 89(2), 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, N., Nandy, D., Saunders, A., & Song, K. (2011). Do hedge funds trade on private information? Evidence from syndicated lending and short-selling. Journal of Financial Economics, 99(3), 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. C. (1987). A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. The Journal of Finance, 42(3), 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13(2), 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Officer, M. S., Poulsen, A. B., & Stegemoller, M. (2009). Target-firm information asymmetry and acquirer returns. Review of Finance, 13(3), 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petacchi, R. (2015). Information asymmetry and capital structure: Evidence from regulation FD. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 59(2), 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyravan, L. (2020). Financial reporting quality and dual-holding of debt and equity. The Accounting Review, 95(5), 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyravan, L., & Wittenberg-Moerman, R. (2022). Institutional dual-holders and managers’ earnings disclosure. The Accounting Review, 97(3), 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pownall, G., Wasley, C., & Waymire, G. (1993). The stock price effects of alternative types of management earnings forecasts. The Accounting Review, 68(4), 896–912. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, K., Shivakumar, L., & Tamayo, A. (2013). Target’s earnings quality and bidders’ takeover decisions. Review of Accounting Studies, 18, 1050–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J. L., & Stocken, P. R. (2005). Credibility of management forecasts. The Accounting Review, 80(4), 1233–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, C. (2005, June 20). The new insider trading? Investment Dealers’ Digest Magazine. [Google Scholar]

- Shroff, N., Sun, A. X., White, H. D., & Zhang, W. (2013). Voluntary disclosure and information asymmetry: Evidence from the 2005 securities offering reform. Journal of Accounting Research, 51(5), 1299–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sletten, E. (2012). The effect of stock price on discretionary disclosure. Review of Accounting Studies, 17(1), 96–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer, L., Thiagarajan, S. R., & Walther, B. R. (2000). Earnings preannouncement strategies. Review of Accounting Studies, 5, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S., Zeng, Y., & Zhou, B. (2021). Information asymmetry, cross-listing, and post-M&A performance. Journal of Business Research, 122, 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Standard & Poor’s. (2011). A guide to the loan market. Standard & Poor’s. [Google Scholar]

- Sufi, A. (2007). Information asymmetry and financing arrangements: Evidence from syndicated loans. The Journal of Finance, 62(2), 629–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, R. E. (2001). Essays on disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32(1), 97–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I. Y. (2007). Private earnings guidance and its implications for disclosure regulation. The Accounting Review, 82(5), 1299–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, M. (1995). Disclosure policy, information asymmetry, and liquidity in equity markets. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11(2), 801–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y., & Yang, X. (2022). Analyst recommendations: Evidence on hedge fund activism and managerial ability. Review of Pacific Basin Financial Markets and Policies, 25(01), 2250004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. (2017). Institutional dual holdings and risk shifting: Evidence from corporate innovation (Working paper). University of Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., & Chen, W. (2021). The joint effects of macroeconomic uncertainty and cyclicality on management and analyst earnings forecasts. Journal of Economics and Business, 116, 106006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., & Kazemi, H. B. (2020). Holdings concentration and hedge fund investment strategies. The Journal of Alternative Investments, 22(4), 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., Kazemi, H. B., & Sherman, G. M. (2021). Hedge funds and prime brokers: Favorable IPO allocations. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 47(8), 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L. (2016). The informational feedback effect of stock prices on management forecasts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 61(2), 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Panel A: Distribution by Year | |||

| Year | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| 2005 | 8 | 1.51 | 1.51 |

| 2006 | 26 | 4.90 | 6.41 |

| 2007 | 1 | 0.19 | 6.60 |

| 2008 | 269 | 50.66 | 57.26 |

| 2009 | 214 | 40.30 | 97.56 |

| 2010 | 1 | 0.19 | 97.75 |

| 2011 | 2 | 0.38 | 98.13 |

| 2012 | 0 | 0.00 | 98.13 |

| 2013 | 0 | 0.00 | 98.13 |

| 2014 | 0 | 0.00 | 98.13 |

| 2015 | 9 | 1.69 | 99.82 |

| 2016 | 1 | 0.19 | 100 |

| Total | 531 | 100 | |

| Panel B: Distribution by Industry | |||

| Industry | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| 1—Consumer NonDurables | 41 | 7.72 | 7.72 |

| 2—Consumer Durables | 16 | 3.01 | 10.73 |

| 3—Manufacturing | 67 | 12.62 | 23.35 |

| 4—Energy | 33 | 6.21 | 29.57 |

| 5—Chemicals | 22 | 4.14 | 33.71 |

| 6—Business Equipment | 55 | 10.36 | 44.07 |

| 7—Telecom | 26 | 4.90 | 48.96 |

| 8—Utilities | 55 | 10.36 | 59.32 |

| 9—Retail | 40 | 7.53 | 66.85 |

| 10—Health | 37 | 6.97 | 73.82 |

| 11—Finance | 68 | 12.81 | 86.63 |

| 12—Other | 71 | 13.37 | 100.00 |

| Total | 531 | 100.00 | |

| Panel A: Distributional Statistics of Treatment Observations | |||||

| Variables | Mean | Median | Std Dev | Q1 | Q3 |

| Spread | 0.160 | 0.128 | 0.129 | 0.099 | 0.178 |

| AIM | 0.022 | 0.005 | 0.074 | 0.002 | 0.013 |

| LnNumAF | 2.692 | 2.773 | 0.533 | 2.303 | 3.091 |

| LnSize | 8.391 | 8.341 | 1.392 | 7.373 | 9.439 |

| ROA | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.071 | 0.023 | 0.086 |

| MTB | 2.378 | 1.902 | 2.522 | 1.297 | 3.057 |

| PerctInst | 0.793 | 0.809 | 0.196 | 0.689 | 0.918 |

| Frequency | 0.944 | 1.099 | 0.540 | 0.693 | 1.386 |

| Precision | −0.191 | −0.109 | 0.321 | −0.202 | −0.054 |

| LnHorizon | 4.062 | 4.159 | 0.545 | 4.007 | 4.263 |

| LnPRC | 3.421 | 3.270 | 1.221 | 2.899 | 3.764 |

| Point | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.331 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Loss | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.171 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Panel B: Distributional Statistics of Control Observations | |||||

| Variables | Mean | Median | Std Dev | Q1 | Q3 |

| Spread | 0.156 | 0.134 | 0.094 | 0.101 | 0.180 |

| AIM | 0.017 | 0.005 | 0.039 | 0.002 | 0.013 |

| LnNumAF | 2.739 | 2.833 | 0.588 | 2.398 | 3.135 |

| LnSize | 8.297 | 8.283 | 1.233 | 7.389 | 9.252 |

| ROA | 0.060 | 0.055 | 0.087 | 0.022 | 0.103 |

| MTB | 2.651 | 2.015 | 2.274 | 1.347 | 3.160 |

| PerctInst | 0.641 | 0.747 | 0.338 | 0.490 | 0.879 |

| Frequency | 1.093 | 1.099 | 0.508 | 1.099 | 1.386 |

| Precision | −0.202 | −0.133 | 0.244 | −0.229 | −0.065 |

| LnHorizon | 4.070 | 4.159 | 0.595 | 4.007 | 4.263 |

| LnPRC | 3.145 | 3.219 | 0.645 | 2.790 | 3.557 |

| Point | 0.093 | 0.000 | 0.290 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Loss | 0.051 | 0.000 | 0.221 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Dependent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Spread | AIM | |

| (1) | (2) | |

| Constant | 0.958 *** | 0.757 *** |

| (14.16) | (18.34) | |

| Post | −0.009 *** | 0.019 *** |

| (−3.31) | (11.64) | |

| Treat | 0.011 * | 0.01 *** |

| (1.77) | (2.63) | |

| Post * Treat | 0.022 ** | 0.014 *** |

| (2.55) | (2.65) | |

| LnNumAF | −0.024 *** | −0.011 *** |

| (−8.52) | (−6.47) | |

| LnSize | −0.03 *** | −0.026 *** |

| (−21.02) | (−30.36) | |

| ROA | −0.265 *** | −0.049 *** |

| (−16.07) | (−4.85) | |

| MTB | −0.002 *** | 0.001 * |

| (−2.8) | (1.77) | |

| PerctInst | −0.054 *** | −0.029 *** |

| (−13.3) | (−11.78) | |

| M&A Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 10,710 | 10,710 |

| R-squared | 23.1% | 21.1% |

| Adjusted R-squared | 22.9% | 20.9% |

| Note: | * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01 | |

| Dependent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Precision | |

| (1) | (2) | |

| Constant | 1.124 *** | −0.672 *** |

| (6.78) | (−5.28) | |

| Post | 0.039 * | −0.074 *** |

| (1.67) | (−4.84) | |

| Treat | −0.129 *** | −0.041 |

| (−3.41) | (−1.63) | |

| Post * Treat | 0.102 * | 0.104 *** |

| (1.93) | (2.91) | |

| LnNumAF | 0.133 ** | 0.018 |

| (5.47) | (1.01) | |

| LnSize | −0.04 *** | −0.005 |

| (−3.46) | (−0.60) | |

| ROA | 0.641 *** | 0.516 *** |

| (4.54) | (4.40) | |

| MTB | −0.011 ** | 0.028 *** |

| (−2.34) | (6.33) | |

| PerctInst | 0.004 | 0.031 |

| (0.12) | (1.34) | |

| LnHorizon | −0.034 *** | |

| (−3.21) | ||

| LnPRC | 0.13 *** | |

| (13.00) | ||

| Point | 0.271 *** | |

| (11.46) | ||

| Loss | −0.381 *** | |

| (−13.48) | ||

| M&A Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 2154 | 2841 |

| R-squared | 4.17% | 25.33% |

| Adjusted R-squared | 3.16% | 24.64% |

| Note: | *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 | |

| Dependent Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spread | Frequency | AIM | Frequency | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Constant | 0.958 *** | −1.114 | 0.757 *** | −1.008 |

| (14.16) | (−1.03) | (18.34) | (−0.91) | |

| Post | −0.009 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.019 *** | −0.104 |

| (−3.31) | (3.39) | (11.64) | (−1.20) | |

| Treat | 0.011 * | −0.197 *** | 0.01 *** | −0.202 *** |

| (1.77) | (−3.30) | (2.63) | (−2.90) | |

| Post * Treat | 0.022** | 0.014 *** | ||

| (2.55) | (2.65) | |||

| 5.102 ** | 7.490* | |||

| (2.10) | (1.93) | |||

| LnNumAF | −0.024 *** | 0.245 *** | −0.011 *** | 0.215 *** |

| (−8.52) | (3.91) | (−6.47) | (4.40) | |

| LnSize | −0.03 *** | 0.113 | −0.026 *** | 0.155 |

| (−21.02) | (1.55) | (−30.36) | (1.52) | |

| ROA | −0.265 *** | 1.992 *** | −0.049 *** | 1.009 *** |

| (−16.07) | (3.02) | (−4.85) | (4.25) | |

| MTB | −0.002 *** | −0.002 | 0.001 * | −0.016 *** |

| (−2.80) | (−0.32) | (1.77) | (−2.97) | |

| PerctInst | −0.054 *** | 0.278 ** | −0.029 *** | 0.22* |

| (−13.3) | (2.06) | (−11.78) | (1.88) | |

| M&A Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 10,710 | 2088 | 10,710 | 2154 |

| R-squared | 23.1% | 4.00% | 21.1% | 4.17% |

| Adjusted R-squared | 22.9% | 3.07% | 20.9% | 3.18% |

| Note: | * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01 | |||

| Dependent Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spread | Precision | AIM | Precision | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Constant | 0.958 *** | −2.892 *** | 0.757 *** | −2.843 *** |

| (14.16) | (−3.84) | (18.34) | (−3.76) | |

| Post | −0.009 *** | −0.033 * | 0.019 *** | −0.219 *** |

| (−3.31) | (−1.96) | (11.64) | (−3.78) | |

| Treat | 0.011 * | −0.102 * | 0.010 *** | −0.116 ** |

| (1.77) | (−2.50) | (2.63) | (−2.48) | |

| Post * Treat | 0.022** | 0.014 *** | ||

| (2.55) | (2.65) | |||

| 5.060 *** | 7.630 *** | |||

| (3.00) | (2.91) | |||

| LnNumAF | −0.024 *** | 0.133 *** | −0.011 *** | 0.101 *** |

| (−8.52) | (2.99) | (−6.47) | (2.97) | |

| LnSize | −0.03 *** | 0.146 *** | −0.026 *** | 0.194 *** |

| (−21.02) | (2.89) | (−30.36) | (2.82) | |

| ROA | −0.265 *** | 1.885 *** | −0.049 *** | 0.891 *** |

| (−16.07) | (4.10) | (−4.85) | (5.16) | |

| MTB | −0.002 *** | 0.036 *** | 0.001 * | 0.023 *** |

| (−2.80) | (6.53) | (1.77) | (4.94) | |

| PerctInst | −0.054 *** | 0.305 *** | −0.029 *** | 0.252 *** |

| (−13.30) | (3.23) | (−11.78) | (3.14) | |

| LnHorizon | −0.036 *** | −0.034 *** | ||

| (−3.26) | (−3.21) | |||

| LnPRC | 0.132 *** | 0.13 *** | ||

| (12.82) | (13.00) | |||

| Point | 0.273 *** | 0.271 *** | ||

| (10.97) | (11.46) | |||

| Loss | −0.384 *** | −0.381 *** | ||

| (−13.22) | (−13.48) | |||

| M&A Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 10,710 | 2734 | 10,710 | 2841 |

| R-squared | 23.1% | 25.31% | 21.1% | 25.33% |

| Adjusted R-squared | 22.9% | 24.65% | 20.9% | 24.64% |

| Note: | * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Yang, X. Does Information Asymmetry Affect Firm Disclosure? Evidence from Mergers and Acquisitions of Financial Institutions. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020064

Chen B, Chen W, Yang X. Does Information Asymmetry Affect Firm Disclosure? Evidence from Mergers and Acquisitions of Financial Institutions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(2):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020064

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Bing, Wei Chen, and Xiaohui Yang. 2025. "Does Information Asymmetry Affect Firm Disclosure? Evidence from Mergers and Acquisitions of Financial Institutions" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 2: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020064

APA StyleChen, B., Chen, W., & Yang, X. (2025). Does Information Asymmetry Affect Firm Disclosure? Evidence from Mergers and Acquisitions of Financial Institutions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(2), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020064