Audit Quality and Family Ownership: The Mediating Effect of Boards’ Gender Diversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background: Agency Theory, Family Business Theory, Institutional Theory, and Stakeholder Theory

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses

3.1. Audit Quality and Family Ownership

3.2. Family Ownership and Board Gender Diversity

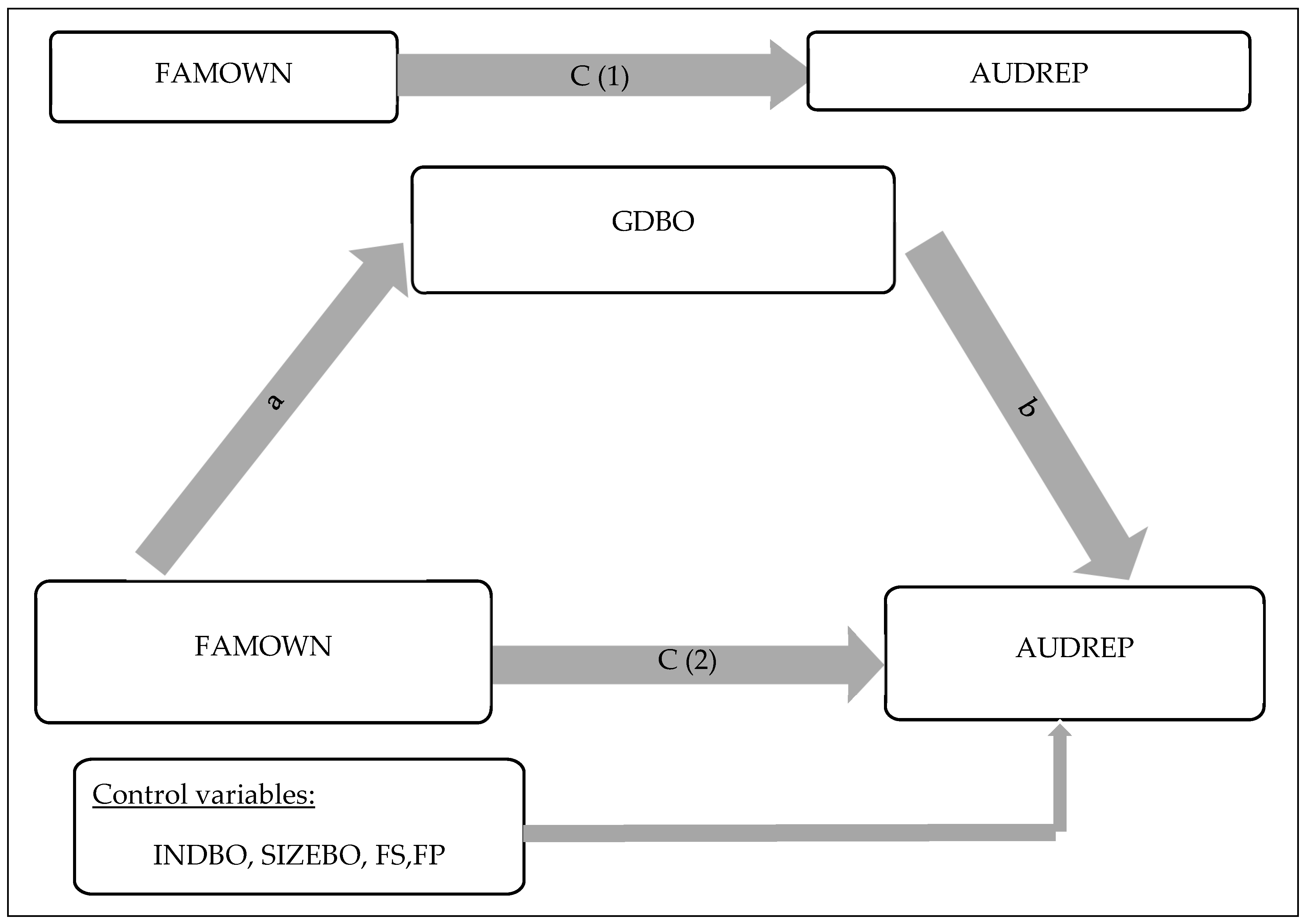

3.3. The Mediating Role of Board Gender Diversity

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Regressions and Variables

4.3. Structural Equation Model (SEM)

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

5.2. Correlation Analysis

5.3. Discussion

5.4. Robustness Check

5.5. Endogeneity Test

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

| 1 | Vision 2030 is a strategic plan aimed at diversifying the economy using non-oil resources, empowering citizens, fostering a dynamic environment for local and international investors, and positioning Saudi Arabia as a global leader. |

References

- Abbasi, K., Ashraful, A., & Bhuiyan, M. B. (2020). Audit committees, female directors and the types of female and male financial experts: Further evidence. Journal of Business Research, 114, 186−197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Meguid, A., Abuzeid, M., El-Helaly, M., & Shehata, N. (2023). The relationship between board gender diversity and audit quality in Egypt. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu Alkhazaleh, Q. K., Amirul, S., & Ghazali, W. (2024). The mediating role of investment efficiency on the relationship between earnings quality and firm performance. International Journal of Academic Research, 14(1), 2225–8329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abudy, M., Amir, E., & Shust, E. (2024). Are family firms less audit-risky? Analysing audit fees, hours and rates. Accounting and Business Research, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sharawi, H. H. M. (2022). The impact of ownership structure on external audit quality: A comparative study between Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 19(2), 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdullah, R. J., & Al Ani, M. K. (2021). The impacts of interaction of audit litigation and ownership structure on audit quality. Future Business Journal, 7(19), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladwey, L., & Diab, A. (2023). The determinants and effects of the early adoption of IFRS 15: Evidence from a developing country. Cogent Business and Management, 10(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faryan, A. M. S., & Dockery, E. (2021). Testing for efficiency in the Saudi stock market: Does corporate governance change matter? Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 57(3), 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, M., & Rhodes, M. (2015). Family ownership, corporate governance and performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 7(2), 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaadi, K. S., Abidin, S. B., & Hassan, W. K. (2021). Audit fees and audit quality: Evidence from Gulf Cooperation council region. AD-Minister, 38, 121–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musali, M. A., Qeshta, M. H., Al-Attafi, M. A., & Al-Ebel, A. M. (2019). Ownership structure and audit committee effectiveness: Evidence from top GCC capitalized firms. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 12(3), 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawashdeh, B. (2021). The effect of family-owned enterprises on the quality of auditing systems. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25(1), 1–11. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/the-effect-of-familyowned-enterprises-on-the-quality-of-auditing-systems-10553.html (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Alshareef, M. N. (2024). Does family ownership moderate the relationship between board gender and capital structure of Saudi-listed firms? Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Alsmairat, Y. Y., Yusoff, W. S., & Ali, M. A. (2019). The effect of audit tenure and audit firm size on the audit quality: Evidence from Jordanian auditors. International Journal of Business and Technopreneurship, 9(1), 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, S. (2023). Gender diversity on corporate boards and earnings management: Evidence for European Union listed firms. Cogent Business and Management, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J. D., & Hull, P. (2023). Instrumental variables methods reconcile intention-to-screen effects across pragmatic cancer screening trials. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(51), e2311556120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ararat, M., Aksu, M. H., & Tansel, A. T. (2010). The impact of board diversity on boards’ monitoring intensity and firm performance: Evidence from the Istanbul stock exchange. SSRN Electronic Journal, 90(216), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoury, N., & Bouri, E. (2015). Principal–principal conflicts in Lebanese unlisted family firms. Journal of Management & Governance, 19(2), 461–493. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Ali, C., & Lesage, C. (2014). Audit fees in family firms: Evidence from U.S. listed companies. The Journal of Applied Business Research, 3(3), 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bilal, C. S., & Komal, B. (2018). Audit committee financial expertise and earnings quality: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research, 84(C), 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2021). Micro econometrics using Stata (Revised ed.). Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D. A., Simkins, B. J., & Simpson, W. G. (2003). Corporate governance, board diversity and firm value. The Financial Review, 38, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbel, S., Bouri, E., & Samara, G. (2013). Impact of family involvement in ownership management and direction on financial performance of the Lebanese firms. International Strategic Management Review, 1, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. C. (2000). Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53(6), 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmadi, S. (2016). Ownership concentration, family control, and auditor choice. Asian Review of Accounting, 24(1), 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelo, L. E. (1981). Auditor size and auditor quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P., Ge, W., & Schrand, C. (2010). Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 344–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 275–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasoulas, M., Chytis, E., Lekarakou, E., & Tasios, E. (2024). Auditor choice, board of directors’ characteristics and ownership structure evidence from Greece. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 13(1), 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filser, A., De Massis, J., Gast, Kraus, S., & Niemand, T. (2018). Tracing the roots of innovativeness in family SMEs: The effect of family functionality and socioemotional wealth. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(4), 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossung, M. F., Fotoh, L. E., & Lorentzon, J. (2020). Determinants of audit expectation gap: The case of Cameroon. Accounting Research Journal, 33(4/5), 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Meca, E., Domingo, J., & Santana, M. (2022). Board gender diversity and performance in family firms. Review of Managerial Science, 17, 1559–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. A., & Tang, C. Y. (2015). Assessing financial reporting quality of family firms: The auditors’ perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 60(1), 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M., Uman, T., Hiebl, M. R., & Seifner, S. (2024). Auditing in family firms: Past trends and future research directions. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(6), 3119–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizani, M., & Abdalkrim, G. (2021). Ownership structure and audit quality: The mediating effect of board independence. Corporate Governance, 21(5), 754–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2010). Essentials of econometrics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, A. J., Wu, M., Bhuiyan, B. U., & Sun, X. (2019). Determinants of auditor choice: Review of the empirical literature. International Journal of Auditing, 23(2), 308–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. L., & Kang, F. (2013). Auditor choice and audit fees in family firms: Evidence from the S&P 1500. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 32(4), 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, O. K., Thomas, W. B., & Vyas, D. (2013). Financial reporting quality of U.S. private and public firms. The Accounting Review, 88(5), 1715–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huse, M. (2007). Boards, governance and value creation: The human side of corporate governance. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A., Ikra, S. S., Saona, P., & Azad, M. A. K. (2023). Board gender diversity and firm performance: New evidence from cultural diversity in the boardroom. LBS Journal of Management & Research, 21(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, A., & Emad, A. (2017). The extent of voluntary corporate disclosure in the Egyptian stock exchange. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 7(2), 266–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Mihret, D. G., & Muttakin, M. B. (2016). Corporate political connections, agency costs and audit quality. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 24(4), 357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K. M. Y., Bin Srinidhi, B., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. S. L. (2017). Board gender diversity, auditor fees, and auditor choice. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(3), 1681–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. C., Cheol, S., Rhee, M., & Yoon, J. (2018). Foreign monitoring and audit quality: Evidence from Korea. Sustainability, 10(9), 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Jimenez, R. (2009). Research on women in family firms: Current status and future directions. Family Business Review, 22, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S., Hossain, M., & Deis, D. (2007). The empirical relationship between ownership characteristics and audit fees. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 28(3), 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, M., & Ahmad, A. C. (2011). Agency theory and managerial ownership: Evidence from Malaysia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 26(5), 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S. P., & Mohamed-Rusdi, N. F. (2015). Ownership structures influence on audit fee. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 5(4), 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, M., Niskanen, J., & Laukkanen, V. (2010). The debt agency costs of family ownership in small and micro firms. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 11(3), 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pious, O., Arthur, B., Bimpong, P., & Kyeremeh, G. (2022). The impact of board characteristics on audit quality, evidence-based on listed firms in Ghana. International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Research, 6(10), 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, K., & Bhatnagar, N. (2013). Professionalization of Family Business: Managing Process and Governance Challenges. Indian School of Business WP, 3032864. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, A., Yousaf, A., & Alharbi, J. (2017). Family and state ownership, internationalization and corporate board-gender diversity: Evidence from China and India. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24(2), 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, Z., & Al Lawati, H. (2023). Board gender diversity and firm performance: The moderating role of financial technology. Competitiveness Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. R. (2008). Approaching Adulthood: The Maturing of Institutional Theory. Theory and Society, 37, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, O. I., Alsmady, A. A., Rahman, R. A., & Alsayegh, M. F. (2022). Corporate governance mechanisms, royal family ownership and corporate performance: Evidence in gulf cooperation council (GCC) market. Heliyon, 8(12), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odudu, A. S., Okpanachi, J., & Yahaya, A. O. (2019). Family and foreign ownership and audit quality of listed manufacturing firms in Nigeria. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 19(1), 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zalata, A. M., Tauringana, V., & Tingbani, I. (2017). Audit committee financial expertise, gender, and earnings management: Does gender of the financial expert matter. International Review of Financial Analysis, 55, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehri, F., & Zgarni, I. (2020). Internal and external corporate governance mechanisms and earnings management: An international perspective. Accounting and Management Information Systems, 19(1), 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zehri, F., Alromayyan, N., & Ezaagui, N. (2023). IFRS adoption, corporate governance and information quality: Evidence from KSA. International Journal of Business Ethics and Governance, 6(1), 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgarni, I., Halioui, K., & Zehri, F. (2016). Effective audit committee, audit quality and earnings management: Evidence from Tunisia. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 6(2), 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Z., & Yu, Y. (2016). Does board independence affect audit fees? Evidence from recent regulatory reforms. European Accounting Review, 25(4), 793–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Panel A: Sample Selection Process | ||

| Description | No. of companies | No. of obs. |

| Total number of observations | 330 | 2310 |

| Less, financial companies/observations | (25) | (175) |

| Remaining number of observations | 305 | 2135 |

| Less, missing observations | (104) | (728) |

| Final sample | 201 | 1407 |

| Panel B: Sample According to Sectors | ||

| Industries | No. of companies | Percentage |

| Customer services | 29 | 14% |

| Material | 19 | 9% |

| Industrials | 72 | 36% |

| Health care | 26 | 13% |

| Foods and beverages | 10 | 5% |

| Energy | 13 | 7% |

| Media | 12 | 6% |

| Real estate | 20 | 10% |

| Total | 210 | 100% |

| Dependent variable: audit quality | Code | Variables | Definition | Authors |

| AUDREP AUDFEES (This variable is used in the robustness check analysis) | Auditor reputation Audit fees | Dummy variable: 1 if auditor is part of Big 4, 0 otherwise Natural logarithm of audit fees | Zehri and Zgarni (2020) Al Sharawi (2022) | |

| Independent variables | FAMOWN | Family ownership | Percentage of shares held by family members | Guizani and Abdalkrim (2021) |

| Meditator and independent variable | GDBO | Board gender diversity | Percentage of female directors serving on company’s board | Aladwey and Diab (2023) |

| Control variables | INDBO | Independence of board | Percentage of non-executive board members to total board members | Zehri and Zgarni (2020) |

| SIZEBO | Size of board | Total number of board members | Pious et al. (2022) | |

| FS | Firm size | Algorithm of total assets | Al-Abdullah and Al Ani (2021) | |

| FP | Firm profitability | Ratio of annual net profit before tax by average total assets | Al-Musali et al. (2019) |

| Panel A. A Summary of Descriptive Statistics for the Whole Sample (1407 Observations) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

| AUDREP | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0 | 1 |

| AUDFEES | 6.5 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 11.1 |

| FAMOWN | 0.52 | 2.49 | 0 | 0.82 |

| GDBO | 0.29 | 14.71 | 0 | 0.39 |

| INDBO | 0.41 | 11.2 | 0.23 | 0.6 |

| SIZEBO | 6.1 | 0.31 | 4 | 12 |

| FS | 8.16 | 1.83 | 3.30 | 13.13 |

| FP | 0.9 | 5.34 | −0.85 | 1.68 |

| Variables | Panel B. Descriptive statistics according to family-owned vs. non-family-owned firms | |||

| Family-owned firms (777 observations) | Non-family-owned firms (630 observations) | Mean difference | t-statistic | |

| Mean | Mean | |||

| AUDREP | 0.25 | 0.76 | 0.499 | −3.484 ** |

| AUDFEES | 4.14 | 7.82 | −3.678 | 1.254 * |

| GDBO | 0.16 | 0.35 | −0.189 | 6.267 *** |

| INDBO | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.089 | 4.886 ** |

| SIZEBO | 7.67 | 6.23 | 1.445 | 2.179 |

| FS | 6.34 | 5.98 | 0.358 | 2.356 |

| FP | 0.98 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 5.283 * |

| Panel A: Pearson Correlation Matrix | Panel B: VIF Statistics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | VIF | 1/VIF |

| (1) FAMOWN | 1 | 1.75 | 0.57 | |||||

| (2) GDBO | −0.023 | 1 | 1.06 | 0.94 | ||||

| (0.9) | ||||||||

| (3) INDBO | −0.065 *** | 0.032 *** | 1 | 1.45 | 0.68 | |||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||

| (4) SIZEBO | −0.011 * | 0.026 | −0.021 ** | 1 | 1.23 | 0.81 | ||

| (0.056) | (0.216) | (0.01) | ||||||

| (5) FS | 0.143 ** | 0.102 | 0.235 * | −0.09 | 1 | 1.03 | 0.97 | |

| (0.01) | (0.133) | (0.063) | (0.7) | |||||

| (6) FP | 0.206 ** | −0.042 | 0.235 | 0.65 * | 0.96 *** | 1.00 | 1.37 | 0.72 |

| - | (0.04) | (0.23) | (0.13) | (0.09) | (0.000) | |||

| 1.31 | ||||||||

| Model 1 (AUDREP) | Model 2 (GDBO) | Model 3 (AUDREP) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | p-Value | Coef | p-Value | Coef | p-Value | |

| FAMOWN | −12.14 ** | 0.013 | 1.34 * | 0.06 | −1.288 | 0.248 |

| INDBO | 10.86 | 0.149 | 23.59 * | 0.078 | 70.341 | 0.612 |

| SIZEBO | 2.86 * | 0.03 | 9.386 | 0.134 | −42.309 | 0.573 |

| FS | 0.46 * | 0.09 | 0.326 *** | 0.000 | 5.891 *** | 0.001 |

| FP | 3.7 | 0.403 | 0.634 | 0.30 | 4.33 ** | 0.012 |

| GDBO | 12.57 ** | 0.045 | ||||

| Constant | −35.89 | 0.624 | −4.65 *** | 0.000 | −17.31 | 0.935 |

| R-Squared | 0.352 | 0.267 | 0.396 | |||

| Firm-Year Effect | Yes | |||||

| Hausman Test | 34.64 | 0.000 | 74.06 | 0.000 | 39.74 | 0.000 |

| No of Obs. | 1407 | |||||

| Model 1 (AUDFEES) | Model 2 (GDBO) | Model 3 (AUDFEES) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | p-Value | Coef | p-Value | Coef | p-Value | |

| FAMOWN | −1.14 * | 0.076 | 13.38 ** | 0.026 | −41.288 | 0.58 |

| INDBO | 10.86 | 0.149 | 23.59 * | 0.078 | 30.341 | 0.82 |

| SIZEBO | 2.86 ** | 0.03 | 9.386 | 0.134 | −32.9 * | 0.098 |

| FS | 0.6 * | 0.086 | 0.366 ** | 0.014 | 12.891 *** | 0.001 |

| FP | 3.7 | 0.403 | 0.634 | 0.30 | 4.33 ** | 0.012 |

| GDBO | 1.57 * | 0.067 | ||||

| Constant | 25.73 ** | 0.024 | −20.65 ** | 0.013 | −7.31 | 0.435 |

| R-Squared | 0.127 | 0.298 | 0.37 | |||

| Firm-Year Effect | Yes | |||||

| Hausman Test | 32.64 | 0.000 | 27.36 | 0.000 | 49.44 | 0.000 |

| No. of Obs. | 1407 | |||||

| Independent Variables | Industry and Firm Averages for Family Ownership and Board Gender Diversity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-Value | Partial R2 | Adjusted Partial R2 | |

| FAMOWN | −0.123 | 0.121 | 0.358 | 0.344 |

| GDBO | 12.08 *** | 0.002 | 0.324 | 0.318 |

| Control variables | ||||

| INDBO | 6.85 * | 0.09 | 0.631 | 0.611 |

| SIZEBO | 15.41 *** | 0.000 | 0.519 | 0.425 |

| FS | −12.46 | 0.124 | 0.476 | 0.349 |

| FP | −3.511 * | 0.061 | 0.321 | 0.318 |

| Constant | 23.138 *** | 0.000 | ||

| Obs | 1407 | |||

| Number of years | 7 | |||

| Overidentifying restrictions test | 0.872 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zehri, F. Audit Quality and Family Ownership: The Mediating Effect of Boards’ Gender Diversity. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020049

Zehri F. Audit Quality and Family Ownership: The Mediating Effect of Boards’ Gender Diversity. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(2):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020049

Chicago/Turabian StyleZehri, Fatma. 2025. "Audit Quality and Family Ownership: The Mediating Effect of Boards’ Gender Diversity" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 2: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020049

APA StyleZehri, F. (2025). Audit Quality and Family Ownership: The Mediating Effect of Boards’ Gender Diversity. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(2), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020049