1. Introduction

In recent years, the financial sector has experienced a substantial transformation because of the increasing recognition of global challenges, including climate change (

Riaz et al., 2024), social imbalance, and resource scarceness. Traditional investment and financial paradigms, which are predominantly motivated by the pursuit of financial returns, are being increasingly supplemented by impact investing and sustainable finance (

Lagoarde-Ségot, 2024). These emerging disciplines are designed to produce positive social and environmental outcomes in addition to financial returns (

Höchstädter & Scheck, 2015). In 2007, the Rockefeller Foundation introduced the term

impact investment, referring to a specific category of value-based investment aimed at generating measurable social and environmental benefits alongside economic benefits, even though there is no universally accepted definition of impact investment as of 2025. The Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) defines impact investment as investments that are made with the intention of generating a positive, measurable social, and environmental impact in addition to a financial return (

What you need to know about impact investing—The GIIN, n.d.). Furthermore, impact investment is becoming more important as it addresses urgent global issues such as poverty, inequality, and climate change, while also aligning investment decisions with personal and institutional values (

Talukder & Lakner, 2023). Impact investors can contribute essential funds to businesses organizations that explore solutions to mitigate environmental effect and enhance climate adaptation. Furthermore, impact investment ensures transparency and accountability by emphasizing measurable outcomes and has the potential to influence policy to promote broader systemic change, making it a potent tool for the development of a sustainable, equitable, and prosperous world (

Heeb et al., 2023;

Ülgen & Klapkiv, 2023).

Sustainable finance implies the incorporation of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into financial decision-making to foster long-term economic growth while tackling sustainability issues such as climate change, social inequality, and corporate governance (

Billio et al., 2024). Moreover, sustainable finance has become a fundamental component of contemporary financing and investment strategies (

Çatak, 2023). Sustainable finance has arisen as a significant idea at the convergence of finance and the Sustainable Development Goals (

Joshipura et al., 2024;

Kumar et al., 2022). It promotes long-term economic growth that is both inclusive and environmentally responsible (

Oprisan et al., 2023). Both impact investment and sustainable finance can tackle worldwide issues such as climate change, the depletion of resources, and social inequity by channeling finance towards sustainable initiatives and businesses (

Jiménez-Barandalla & Velasco-Márquez, 2023;

Singhania et al., 2024b). Furthermore, impact investing and sustainable finance aid in reducing risks linked to environmental deterioration and social unrest, hence promoting stability in financial markets (

Botlhale, 2023). They cater to the increasing desire of investors to connect their traditional investment portfolios with green and impact portfolios, thereby stimulating advancements in environmentally friendly technologies and sustainable corporate strategies (

Gigante et al., 2023). In addition, impact investing and sustainable finance ultimately facilitate the shift towards a low-carbon economy, guaranteeing that economic progress does not harm future generations, but instead leads to a more resilient, fair, and flourishing global economy (

Hou et al., 2023). However, Impact investing and sustainable financing is related to triple bottom line (TBL) financing which encompasses the economic, environmental, and social value associated with an investment, closely tied to the idea of sustainable development goals of United Nations (

Hammer & Pivo, 2017). Considering the

triple bottom line, it is recommended that corporate and policy decisions should equally prioritize financial, environmental, and social factors. It is noteworthy that both developed and developing countries are increasingly perceived as mandating SDG attainments through impact investing–sustainable finance, including carbon financing, climate financing, and green financing. Moreover, the combined effect of the EU Taxonomy, EU Green Deal, and Paris Agreement highlights how regulatory and normative frameworks are altering sustainable finance by reducing greenwashing, increasing transparency, and allocating financing to impact-driven projects (

C. H. Yu et al., 2021). The importance of these mechanisms has increased after the announcement of SDGs in 2015, which fosters the global progress toward a sustainable future and highlighted the necessity for resilient, climate-aligned financial systems (

Elavarasan et al., 2021). Investors today are more interested in ESG and socially responsible investment funds, instructing fund managers to evaluate and seek out funds for impact investing (

Alda, 2021). Furthermore, financial markets consistently seek innovative sustainable finance instruments that they can strategically utilize to address economic needs while making significant contributions to sustainability and sustainable development, particularly in relation to achieving the UN agenda 2030 (SDGs) and minimizing carbon emissions in alignment with the Paris Agreement, thereby advancing global sustainability initiatives (

C. H. Yu et al., 2021).

Impact investing and sustainable finance promise to provide an opportunity to significantly contribute to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), thus creating a new avenue for development in the investment and financial landscape (

Sustainable finance impact investing trends [Updated], n.d.). In addition to making money, impact investing tries to make measurable positive changes in society and the environment. It focuses on areas like healthcare, education, renewable energy, and financial inclusion. On the other hand, sustainable finance is a broader strategy that takes ESG factors into account in all areas of finance, such as investments, corporate governance, and financial market regulations (

Joshipura et al., 2024). This is done to protect the economy in the long term while also lowering environmental and social risks. However, these two ideas are related because they both aim to promote responsible economic growth. Sustainable finance establishes a more comprehensive financial structure that bolsters and expands impact investing, which in turn raises funds to tackle urgent global issues including poverty, inequality, and climate change (

Giamporcaro et al., 2023). They push for more inclusive, transparent, and ethical business practices by urging governments, financial institutions, and enterprises to align their strategy with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Together, these strategies contribute to accelerating the world’s shift toward a low-carbon, socially inclusive economy that is more equitable and resilient by addressing both short- and long-term challenges (

Boiral et al., 2024).

The field of impact investment and sustainable finance is multifaceted and dynamic, comprising a diverse array of practices, including microfinance, ESG-integrated portfolios, and social impact bonds (

Lin et al., 2023). The academic literature on the topic is expanding, providing support for this new discipline by investigating its theoretical underpinnings, practical applications, and results. Nevertheless, a bibliometric and networks-based analysis that delineates the conceptual, intellectual structure and evolution of this domain is still urgently required, despite the growing volume of research. By conducting a systematic bibliometric review of the literature on impact investing and sustainable finance, this article tries to resolve this gap. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that identifies the research knowledge and network analysis of impact investment and sustainable finance research domain. This study aims to connect key research themes, noticeable sources, leading authors, words tree networks, thematic maps, topic dendrogram analysis and keyword co-occurrences analysis. We intend to provide a systematic analysis of the current state of knowledge in impact investment and sustainable finance through this bibliometric review, emphasizing critical areas of focus and potential avenues for future study. The goals of the study can be achieved if the researchers approach the following research questions.

RQ 1. What are the trends and number of publications over the study period in this research domain?

RQ 2. Which journals are considered the most productive, and who are the leading authors in this research domain?

RQ 3. Which counties published the highest number of papers?

RQ 4. In what ways have the research themes evolved and transformed over time?

RQ 5. What are the future research directions within this research domain?

This analysis not only enhances comprehension of the field but also provides a valuable resource for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers who are interested in contributing to the rapidly changing landscape of impact investment and sustainable finance.

The structure of the study is outlined as follows:

Section 2 introduces the previous literature related to impact investing and sustainable finance.

Section 3 presents the data, methods, and software used to generate these results.

Section 4 elucidate the results, and discussion, including the descriptive statistics of the dataset, words tree map, thematic map, topic dendrogram, thematic evolution and the co-occurrence of the keywords, of the articles within the research domain. The final section presents conclusions, implications, policy recommendations, limitations, and suggestions for further study.

2. Historical Background of Impact Investment and Sustainable Finance

Over the years, impact investment and sustainable finance have changed a lot. This is as individuals have become more aware of global issues and the need for responsible financial practices. Socially responsible investing (SRI) is where impact investing got its start. SRI started in the 1960s when investors started to think about moral and social issues when choosing investments (

Tripathi & Kaur, 2020). At first, SRI tried to stay away from investments in tobacco, weapons during the apartheid era. It was in the early 2000s that the word “

impact investing” became popular, as investors and businesses looked for ways to make money while also helping people and the environment. When the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) was created in 2009, it was a big step toward making the field official and growing it, with a focus on measurable impact. Today, impact investing focuses on areas like healthcare, financial inclusion, renewable energy, and sustainable agriculture. It helps solve global problems like climate change and inequality.

In the banking industry, sustainable finance has been there since before the industrial revolution. It was in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that Italian banks began to lend money to businesses that had no connection to war or unethical conduct (

Mejia-Escobar et al., 2020). The goal, such as society and the environment coexisting peacefully, remained the same, however, the concept was changed during that time. Sustainable finance as we know it today evolved out of the United Nations Environment Program Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) (

Taking stock of sustainable finance policy developments|Blog post|PRI, n.d.), which formed partnerships with banks and other financial institutions at the 1991 Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit to advance sustainable development (

The G20 energy efficiency finance task group (EEFTG), Activity report 2014–2019|Climate strategy & partners, n.d.), and solidify the concept of sustainable finance. Launched in 1992, the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index provides investors with guidance and evaluation of sustainable instruments (

Manuel Diaz-Sarachaga & Alvarez, 2021). In 2002, as a collaborating institute of the UNEP, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) was established to address the challenge of global monitoring and reporting of sustainable development activities. In 2015, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of sustainable development and sources of sustainable finance were added (

Marín-Rodríguez et al., 2024). The first green bond was issued in 2008 by the World Bank. Several development projects began using green bonds and other sustainable financing instruments after 2015 (

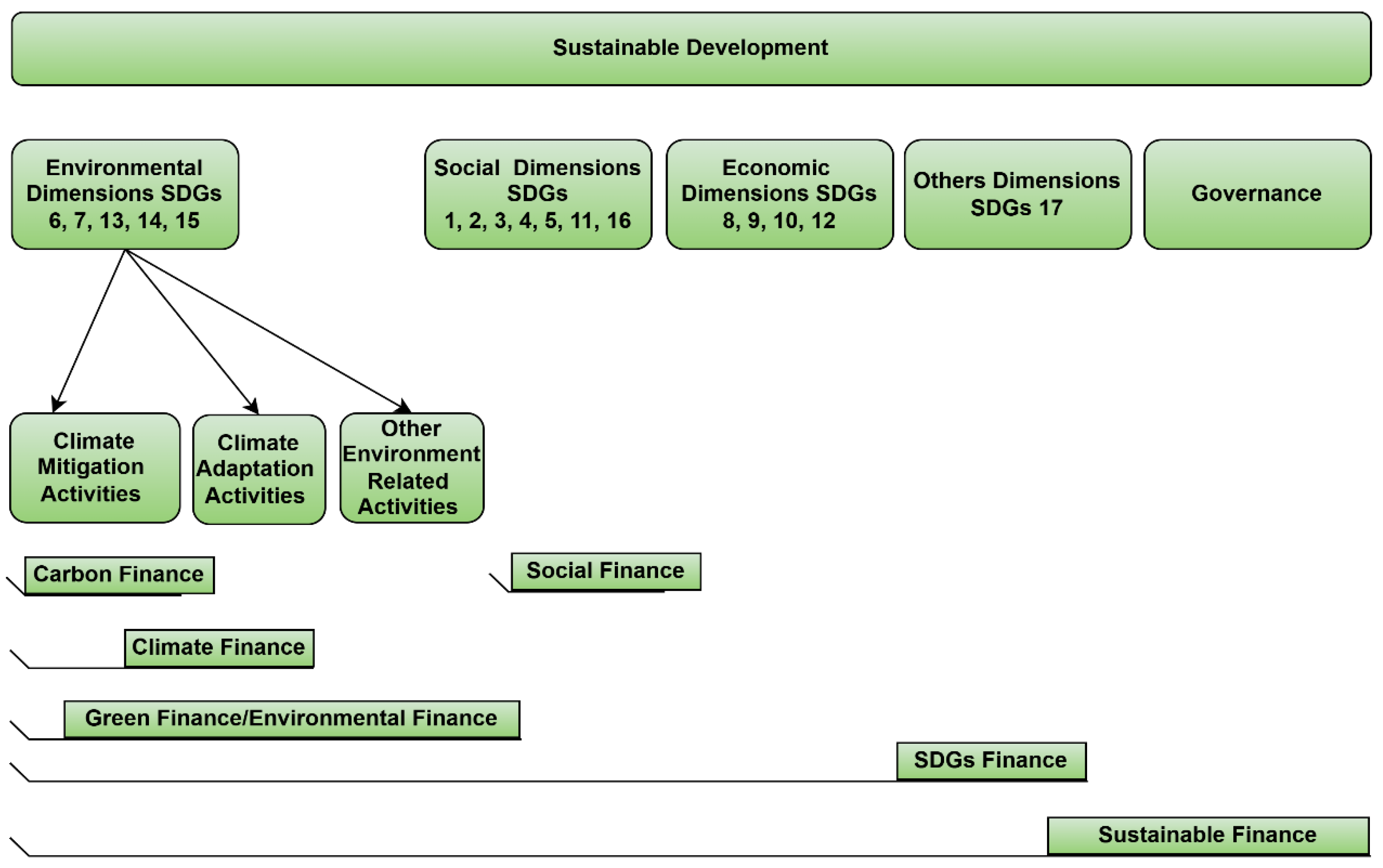

Durmaz et al., 2024). The concept of sustainable finance based on sustainable development is depicted in

Figure 1.

3. Theoretical Foundation, Literature Review of Impact Investing and Sustainable Finance

Various interconnected theoretical frameworks provide theoretical groundwork for the expanding corpus of literature on impact investing and sustainable finance, which in turn explains the evolving institutional settings, behaviors, and motivations behind sustainable financial activities.

Stakeholder Theory (

Edward & David, 1983) is fundamental to this framework, highlighting the necessity of generating value for a diverse range of stakeholders, including shareholders, communities, employees, and the environment. This theory elucidates the growing incorporation of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into investment decisions, as well as the transition towards ethical and responsible finance.

Institutional Theory (

Dimaggio & Powell, 2021) explains how regulatory frameworks, market norms, and global sustainability initiatives, including the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), compel organizations and investors to embrace impact investing and sustainable finance practices. This occurs through coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures, which promote legitimacy and conformity within the financial sector.

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) Theory (

Elkington, 1998) offers a multidimensional framework that expands the definition of organizational success to include social equity (people), environmental stewardship (planet), and economic performance (profit). This framework aligns with the objectives of impact investing and sustainable finance to create comprehensive value. Furthermore, theories of sustainability like the

Systems Theory of Sustainability emphasize the interdependence of economic, social, and environmental systems and promote integrated and long-term investment strategies (

Voinov & Farley, 2007). Another theory is the

Sustainable Development Theory (Brundtland Commission, 1987), which promotes intergenerational equity and development that satisfies current needs without endangering future generations (

Findlay-Brooks, 1985).

Corporate Sustainability Theory elucidates the integration of sustainability within corporate strategies and operations, thereby improving competitiveness and transparency, which subsequently draws sustainable investment (

Kantabutra & Ketprapakorn, 2020). When combined, these theories offer a thorough framework for comprehending the bibliometric analysis’s findings about the institutional embedding, geographic spread, and thematic evolution of impact investment and sustainable finance.

Impact investing and sustainable finance have garnered significant attention in recent years, propelled by the increasing acknowledgement of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions. A diverse range of research has examined multiple aspects of sustainable finance, encompassing access to capital for small farmers, impact investment, the function of sustainable banks, and the convergence of emerging technologies like blockchain. A bibliometric study of 365 articles from 2001 to 2024 offers a comprehensive examination of this expanding research domain, highlighting the necessity for accessible sustainable financial options for small-scale farmers (

Alamsyah et al., 2024). Moreover, the study examines small farmers’ access to sustainable financing techniques, emphasizing the role of agricultural innovations in tackling environmental concerns. Another, comprehensive evaluation of 1269 papers from 1984 to 2021 conducts a broader examination of trends in sustainable finance research. The study delineates the progression of sustainable finance by examining publication trends, thematic emphasis, and worldwide collaboration patterns, thereby elucidating its development and future trajectory (

Singhania et al., 2024b). Impact investment, an essential aspect of sustainable finance, was examined in a bibliometric study that analyzed 753 articles from 2007 to 2024. The research underscores significant trends in the domain, including the necessity of impact measurement and the function of standardized reporting in bolstering the legitimacy of impact investing (

Minimol, 2024). Recent significant studies highlight the increasing importance of green bonds in sustainable financing. Companies are increasingly utilizing these financial tools to demonstrate their environmental commitment. Empirical research indicates mixed results: whereas green bonds have considerable investor interest, they may not consistently generate the expected environmental or social impacts without robust regulatory control (

Flammer, 2021). This highlights the necessity of stringent policies to guarantee that green bonds fulfill their intended objectives. A significant domain in sustainable finance research is sustainable investing (SI), wherein an analysis of 1022 articles from 1991 to 2023 revealed topics like ESG-based portfolios, fiduciary responsibility, and sustainability evaluation procedures. Emerging issues from 2020 to 2023, such as Sustainable Development Goal financing through green bonds and the effects of shareholder involvement, were also examined (

Singhania et al., 2024a). Incorporating ESG into traditional investment methods is not just ethical but also strategically wise for long-term value generation (

Pástor et al., 2021). Study indicates that green assets typically exhibit lower expected returns due to their hedging capabilities and substantial demand from value-oriented investors. This trade-off necessitates enhanced ESG indicators and transparent evaluation frameworks to facilitate informed investment decisions and precise sustainability assessments (

Kumar et al., 2022). Numerous studies indicate that impact investors, especially in venture capital, frequently accept diminished financial returns in pursuit of significant non-financial advantages. This underscores the need of acknowledging varied investment reasons and creating financial products that correspond with value-driven investment objectives (

Pedersen et al., 2021). A hybrid analysis of 528 articles published between 2012 and 2022 shows significant issues such as investor incentives, performance comparisons with conventional investments, and policy enablers. This study provides investors, issuers, and regulators with practical information in the area of financing sustainability (

Joshipura et al., 2024). Another bibliometric review of 421 studies on impact investing that were conducted between 1989 and 2021 reveals major themes such as ecosystem growth, standardized reporting, stakeholder management, improving impact investing methods and avoiding impact washing (

Singhania & Swami, 2024). A case study from Hong Kong highlights how a top-down national policy, working together with market-driven practices, may foster a resilient green finance ecosystem (

Ng, 2018). Technology is progressively regarded as a transformative influence in this domain. Research indicates that Fintech systems such as Clarity AI and Pensumo facilitate sustainable finance by improving transparency, identifying greenwashing, and encouraging ethical financial practices (

Vergara & Agudo, 2021). The utilization of AI, blockchain, and digital technologies enhances customer confidence and the credibility of sustainability assertions. A bibliometric review of 620 studies conducted from November 2008 to January 2022 examines blockchain’s transformational potential in sustainable finance, with a focus on its applications in smart cities and the sharing economy. The amalgamation of blockchain with other technologies, like the Internet of Things (IoT), is regarded as a pivotal catalyst for novel solutions in sustainable financial practices (

Ren et al., 2023). Sustainable banks play a vital role in facilitating sustainability transitions, as evidenced by an analysis of 723 publications from 2001 to 2021. The study examines subjects including bank profitability, risk profiles, and customer reactions to sustainability initiatives. It also analyzed the impact of regulatory measures on the sustainability initiatives of banks (

Kashi & Shah, 2023). Another bibliometric examination of 3786 publications from 2000 to 2021 delineates research patterns and emerging themes in sustainable finance, including green finance, socially responsible investing, and the impact of COVID-19 on investment strategies. The research highlights the growing interest in ESG investment preferences, and the problems associated with low-carbon transitions and green bonds (

Luo et al., 2022).

Table 1 provides an overview of the existing review articles on impact investing and sustainable finance.

Sustainable finance research encompasses a wide array of topics, from micro agricultural finance to the impact of technologies such as blockchain on advancing sustainable financial systems. The incorporation of ESG criteria into investment strategies, coupled with the increasing significance of impact investing, blockchain, and sustainable banking, highlights the sector’s capacity to advance global sustainability objectives. Academic research must persist in tackling critical difficulties, such as impact assessment, policy integration, and the creation of innovative financial instruments that correspond with sustainable development goals.

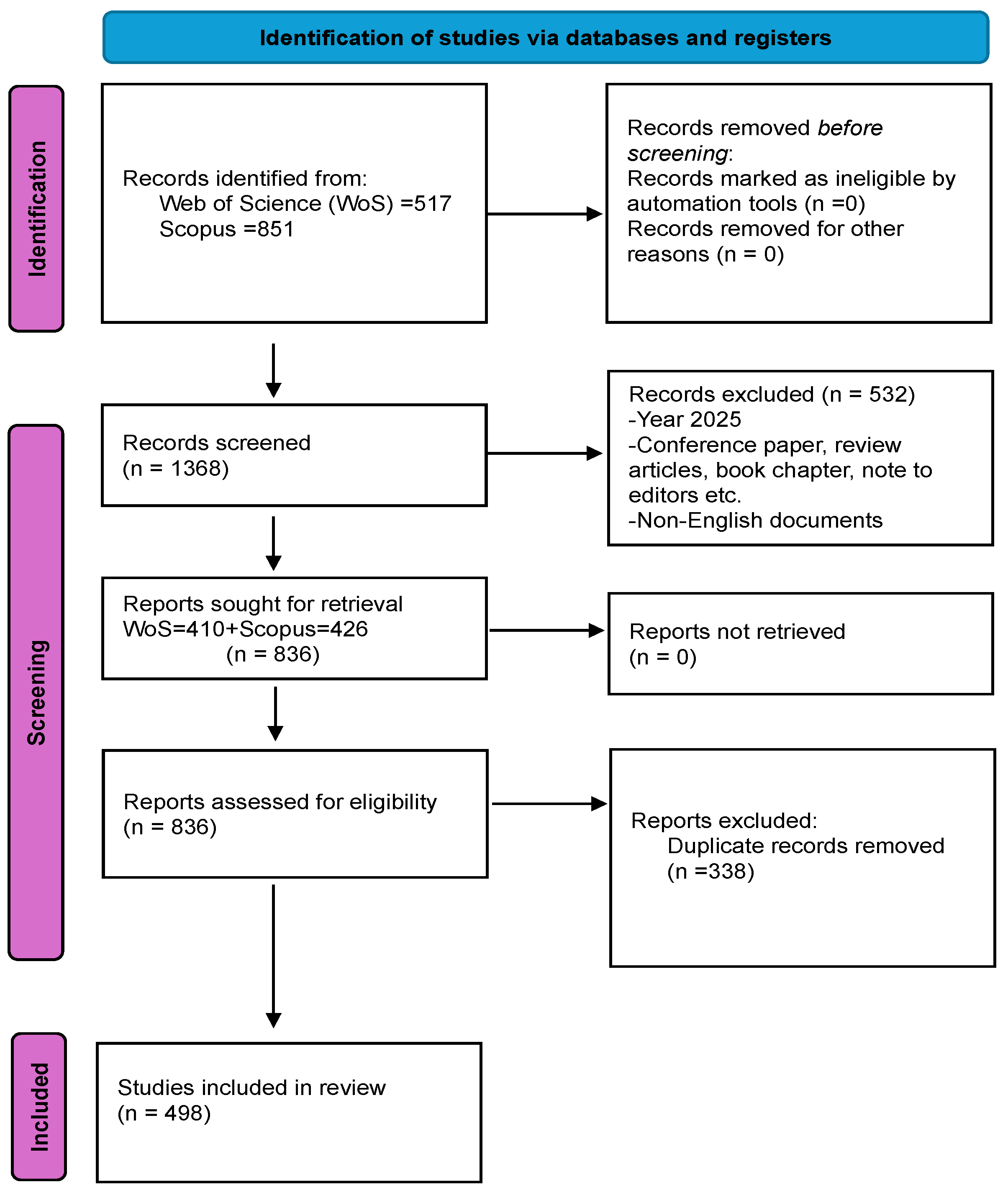

5. Results, Analysis and Discussion

5.1. Main Features of Bibliographic Datasets

In the very first stage of the research, we conducted descriptive statistical analysis to get a general understanding of the most important features of the literature on impact investing and sustainable finance. The key findings of this phase are summarized in

Table 3. The corpus, which consists of 498 documents, is quite extensive and was created by 1238 authors. There is a noticeable growth in the number of publications, as evidenced by the average yearly growth rate of nearly 45.36%. Furthermore, it also signifies a swiftly growing area of study with increased scholarly or research focus. The average age of documents is 2.54 years. Moreover, the dataset also indicates that the level of international collaboration is approximately 29.32%.

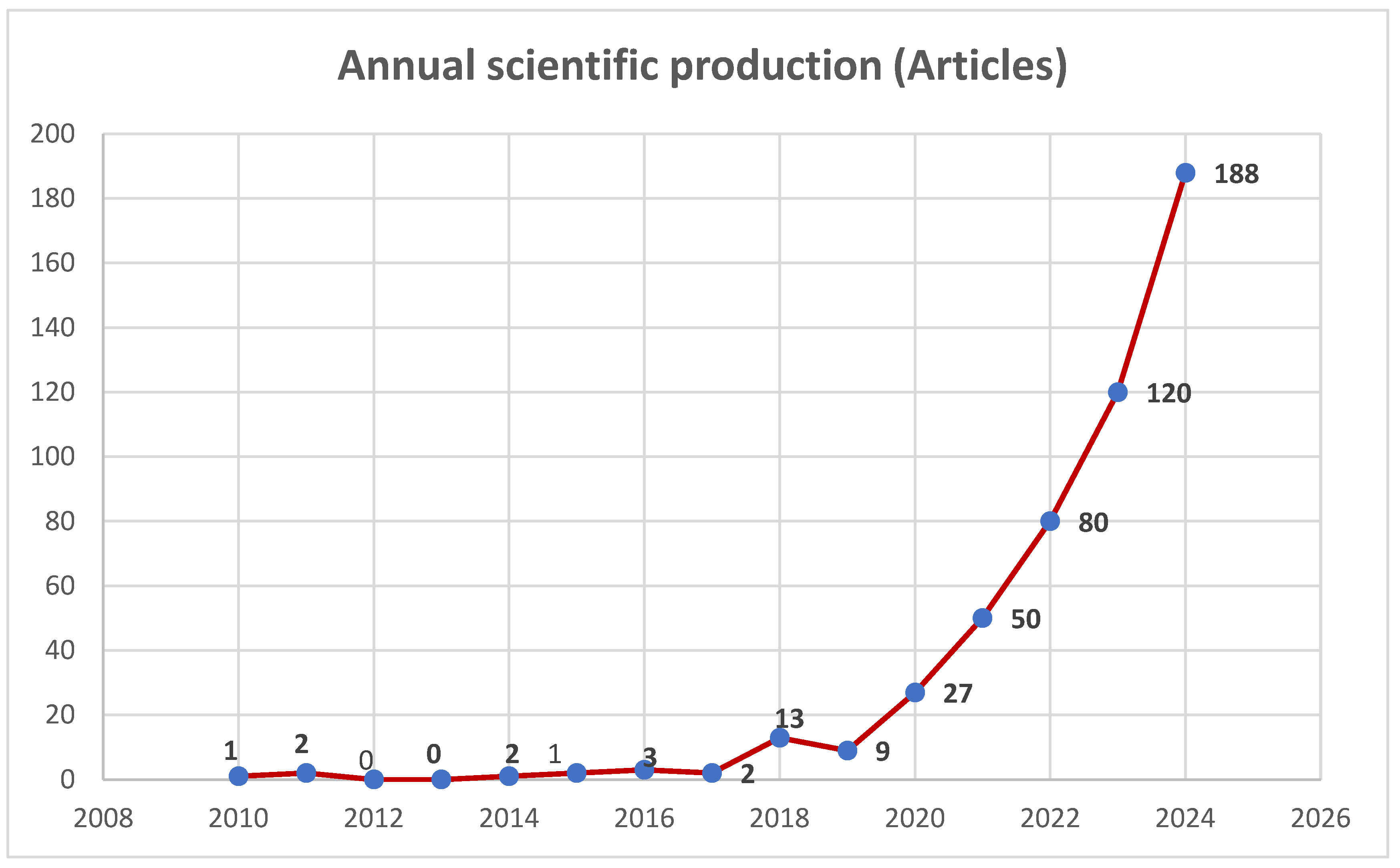

5.2. Annual Scientific Production Overtime

Figure 3 illustrates an upward trend in the number of published articles from 2010 to 2024. The number of publications has experienced a rise, with the annual percentage growth rate reaching 45.36 percent. This suggests a growing interest among experts in impact investing and sustainable finance research domain. The line chart can be divided into two separate time frames according to its trending patterns.

From 2010 to 2019, the rate of article publication was rather sluggish, with fewer than fifteen articles being published each year. Impact investing and sustainable finance are now in the spotlight, and this was just the beginning. This is the initial stage, often known as the introduction phase. The first article in this period, authored by Toshiro Nishizawa is titled Changes in Development Finance in Asia: Trends, Challenges, and Policy Implications. The study identified that development finance in Asia is increasingly transitioning to private and domestic sources, characterized by emerging trends in public–private partnerships and green finance. Strengthening financial intermediaries is a critical challenge for achieving sustainable long-term financing. Over this ten-year period, 33 articles were published, representing 7% of the total articles.

From 2020 to 2024, there was a significant surge in the number of documents published on impact investing and sustainable finance research domain. With 188 articles published in 2024; this year had a high number of publications. There was a total of 465 articles published in this time frame, making up nearly 93% of the total publication. The present era is regarded as a phase of expansion in this area of study. This may explain why, in the post-COVID era, researchers emphasized the development of sustainable financial models that concentrate not only economic profit but also social and environmental benefits to create a more resilient world (

Gao & Hoepner, 2024). In addition to COVID-19’s immediate effects, the rise in publications after 2020 is due to several global policy changes, regulatory advances, and new financial instruments and frameworks. For example, the European Union’s

Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), EU Taxonomy (both going into effect in 2021), the Paris Agreement, and EU Green Deal have pushed investors and academics to pay more attention to sustainable finance frameworks (

Sustainable finance disclosures regulation—European Commission, n.d.). The academic interest in impact investment and sustainable finance grew quickly when it met market practice. This was made possible by digital openness and pressure to align with the Sustainable Development Goals. Another explanation may be that governments, policymakers, and regulatory agencies put an emphasis on the achievement of sustainable development goals. In this era, sustainable finance and impact investing are increasingly popular topics.

5.3. Most Prolific Journals

Table 4 presents the top ten journals that cover impact investing and sustainable finance literature. There was a total of 498 articles analyzed, and they were published in 262 journals. Just ten journals contributed to publishing over 25% (125) of the articles used in the analysis.

Sustainability (37) is the highest-ranked journal in the top ten, followed by

Resources Policy (18), Journal of Cleaner Production (11),

Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment (11), Energy Economics (09), Environmental Science and Pollution Research (09), Journal of Environmental Management (09) and so on. Out of 125 articles that were published in the top ten journals, 73 were published in journals that were ranked by the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS), which ranks publications according to their quality. Within the top ten journals, the ABDC-recognized journals have also published 62 articles. In addition, Scimago ranks each of the ten journals from the first quartiles. Furthermore, Bradford’s Law indicates that 18 journals among the core sources published 165 articles, constituting 33% of the total papers published in this research domain. This underscores the uniqueness and focus of academic contributions within a limited range of journals. However, Bradford’s law categorized the total journals into three zones: zone one comprised 18 journals, zone two contained 80 journals, and zone three included 164 journals. Journals in the third zone predominantly published one articles and in total published 164 Articles.

Figure 4 presents the zone distribution of journals and articles.

5.4. Top Authors

Measuring an author’s significance in a specific field requires an analysis of both their output and impact.

Table 5 analyzes both metrics to provide an overview of the top 10 most productive authors in the domain of impact investing and sustainable finance research. Productivity was quantified by the total count of articles authored by an individual within a specified timeframe. The impact was assessed by analyzing the number of citations received annually. Notable productive authors are Arshian Sharif, Satish Kumar, and Helen Chiappini. However, the output of an author does not inherently indicate the overall quality of their work, and scholars frequently utilize metrics beyond publications numbers to assess their impact.

Table 5 presents the total number of citations (TC), the h-index (h), the m-index (m), and the g-index (g) for the local dataset and the ten most influential authors. The author with the highest citation counts in the local dataset include Arshian Sharif (291), Satish Kumar (259), Ulrich Volz (164), Peterson. K. Ozili (136) and Juan David Gonzalez-Ruiz (70). Notably, these five scholars individually received over seventy citations in their research. Helen Chiappini, Juan David Gonzalez-Ruiz, Satish Kumar, Peterson. K. Ozili, Arshian Sharif, Ulrich Volz are prominent authors in the field of impact investing and sustainable finance, each having an h-index of 3. This metric signifies that they have authored three publications that have garnered at least three citations each (

Hirsch, 2007). The six leading authors, as determined by their H index, have examined the topics of impact investment and sustainable finance from distinct perspectives: inequalities and ethical dilemmas in impact investing and sustainable finance; financial challenges in social impact bonds (SIB); and ESG for the sustainability of financial markets. The g-index was calculated using Biblioshiny to ensure that younger authors were not disproportionately disadvantaged. The g-index represents the cumulative citations number and compared with (g)

2 of productive years of the author. It is essential to acknowledge renowned scholars, including Satish Kumar and Arshian Sharif, as well as emerging researchers like Shamim Akhtar, Ibrahim Tawfeeq Alsedrah and Heba AA Ali, who commenced their publications between 2023 and 2024 and have quickly become influential figures in the discipline. The m-index is measured by dividing the h-index by the number of years an author has been active, which is defined as the years since their initial publication.

Table 5 presents the m index generated by Biblioshiny R. It addresses the issue of the h-index. The index can be advantageous to beginners. Shamim Akhtar and Ibrahim Tawfeeq Alsedrah are important authors in this topic despite their recent emergence in the scholarly arena.

Leading authors and their institutions shape the paradigms of impact investing and sustainable finance by identifying fundamental issues, developing theoretical models, and influencing policies. Helen Chiappini from the University of Chieti-Pescara, Italy, has made significant contributions to sustainable finance, corporate governance, and socially responsible investment strategies. In contrast, Ulrich Volz from SOAS University of London, United Kingdom, focuses on macro-financial resilience, the integration of climate risk, and research in policy-oriented sustainable finance. Satish Kumar (India) describes the intellectual framework of the discipline, while Peterson K. Ozili (Nigeria) examines financial inclusion, digital finance, and governance within emerging markets. Arshian Sharif from Sunway University, Malaysia, focuses on environmental economics, renewable energy, and sustainable growth. In contrast, Juan David Gonzalez-Ruiz from the National University of Colombia examines ESG performance and social impact measurement. Emerging scholars including Shamim Akhtar (China), Md Akhtaruzzaman (Australia), Heba A. A. Ali (Egypt), and Ibrahim Tawfeeq Alsedrah (Saudi Arabia) are contributing to the diversification of perspectives on risk, governance, and the adoption of ESG principles. Even though these authors and their institutions influence impact investing and sustainable finance research, mainstream attention on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and climate finance ignores unexplored topics such as grassroots sustainability and biodiversity financing.

An analysis of the distribution of authors based on their publication number reveals significant concentration, with the majority having published no more than one paper (

Table 6). The disparity in authorship characteristics within a specific field of study is a common phenomenon (

Cox & Chung, 1991). In bibliometrics, this phenomenon is referred to as Lotka’s Law (

Bensman & Smolinsky, 2017;

Rodin & Apriyani, 2021) known as the

inverse square law of scientific productivity.

Table 6 illustrates the actual and theoretical values as per Lotka’s Law. A potential explanation for this phenomenon may be the relatively recent development of the research field. A further explanation is the multi-disciplinary nature of the research arena: some specialists produce articles on impact investing and sustainable finance, yet most of their academic work is focused on other subjects. Another explanation may be the comparatively low level of long-term initiatives and projects focused on impact investing and sustainable finance. Unlike many other disciplines, impact investing and sustainable finance feature a limited number of strategic research projects. Consequently, it appears to be a not sufficiently supported and challenging foundation for developing a long-term academic career in this area of research.

The analysis of the most productive authors provides valuable insights into the current state of the field, particularly indicating that the most developed nations, especially in European countries, are actively conducting research on impact investing and sustainable finance. This fact underscores the necessity for a thorough analysis of publications on this topic in these countries, while also emphasizing the significance of researching this new financial innovation in other regions globally.

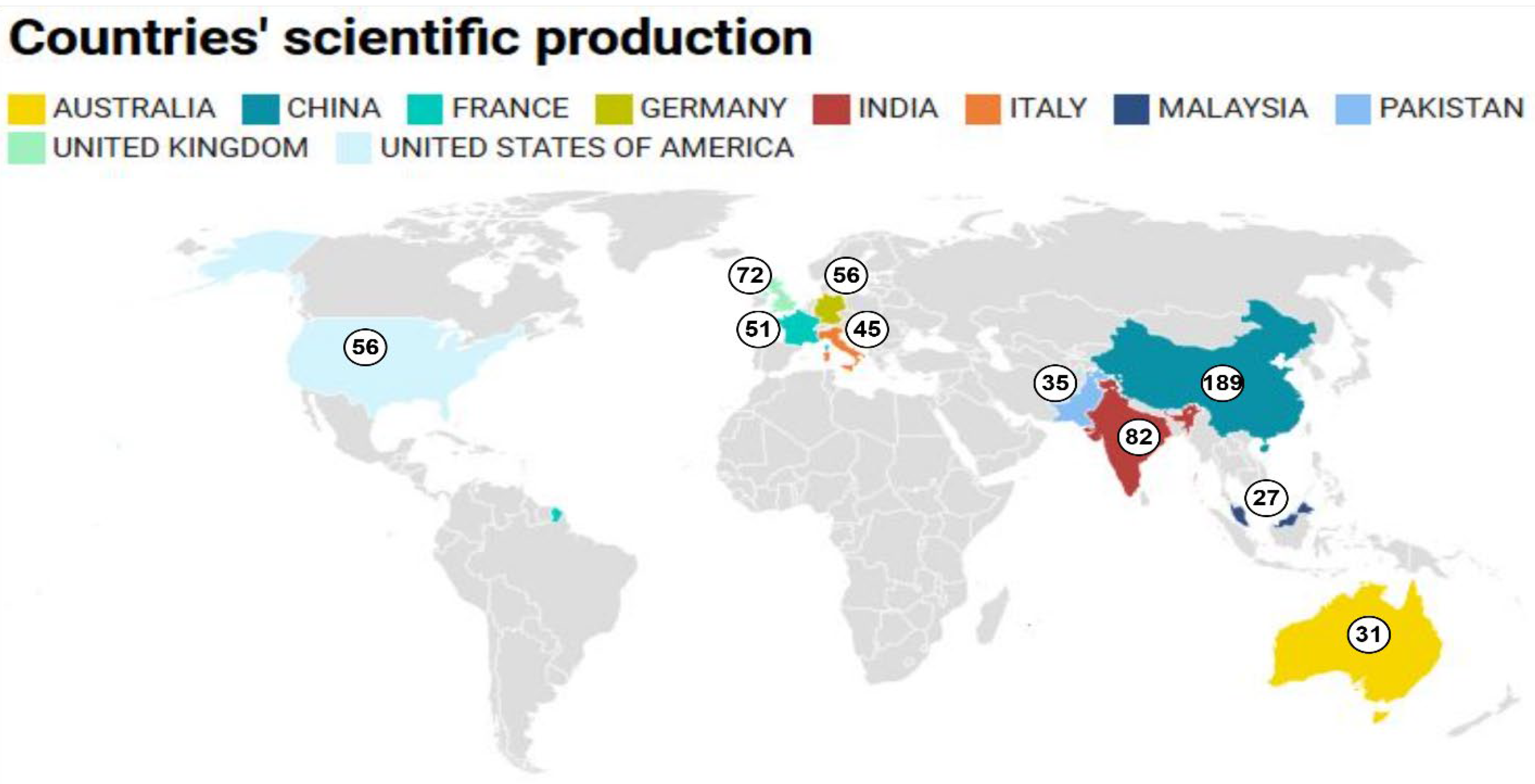

5.5. Countries’ Scientific Production

Figure 5 presents the top ten countries’ research output regarding impact investing and sustainable finance, quantified by the number of publications. China has produced 189 publications, indicating a substantial emphasis on these themes and an increasing role in influencing global impact investing and sustainable finance practices. India and the UK have 82 and 72 publications, respectively, highlighting their significant contributions to the research field. Mid-level contributors comprise Germany (56), the USA (56), France (51) and Italy (45) reflecting significant research initiatives focused on the integration of sustainability into financial systems in these areas. Pakistan (35), Australia (31), and Malaysia (27) are emerging players in this field, offering significant insights into localized strategies for impact investing and sustainable finance.

Figure 5 clearly shows that most of the countries are European. It indicates that Europe places a higher priority on impact investment and sustainable finance research than other regions.

Although publication counts show that China (189), India (82), and the United Kingdom (72) are the primary contributors to research on impact investing and sustainable finance, a more detailed analysis indicates that geographic patterns in research output are influenced by various factors beyond only volume. For instance, China’s government has prioritized sustainability by integrating green finance, carbon neutrality, and ESG principles into its national development agenda. This is evident in initiatives like the 14th Five-Year Plan and commitments to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 (

H. Yu et al., 2024). This robust policy initiative encouraged both scholarly and practical research. China’s extensive financial markets and swift economic growth have generated a demand for sustainable investment instruments (

H. Yu et al., 2024). Additionally, its leadership in renewable energy investment offers a robust foundation for research that connects finance with climate action (

Solangi & Magazzino, 2025). Chinese universities and research institutes have gained from enhanced international collaboration and funding opportunities, thereby increasing their visibility in global academic literature. However, the expanding academic ecosystems in India, along with governmental initiatives that promote green and inclusive finance, have stimulated scholarly interest in these areas. In the United Kingdom, institutional investors and prominent business schools have progressively incorporated ESG and impact themes into mainstream research agendas. The prominence of European countries such as Germany (56), France (51) and Italy (45) indicates significant academic engagement and robust policy frameworks in the region. These include the EU Green Deal, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), and the EU Taxonomy, which collectively promote sustainability-oriented research and practice. Emerging contributors such as Pakistan (35), Australia (31), and Malaysia (27) provide important localized perspectives, frequently focusing on region-specific development challenges including financial inclusion, climate resilience, and SME growth. International collaborations between institutions in the Global North and Global South are increasingly shaping research dynamics and enhancing output visibility.

Figure 5 demonstrates a concentration of output among European countries, which can be more effectively analyzed by considering regulatory environments, research infrastructure, and the strategic prioritization of sustainable finance in various regions.

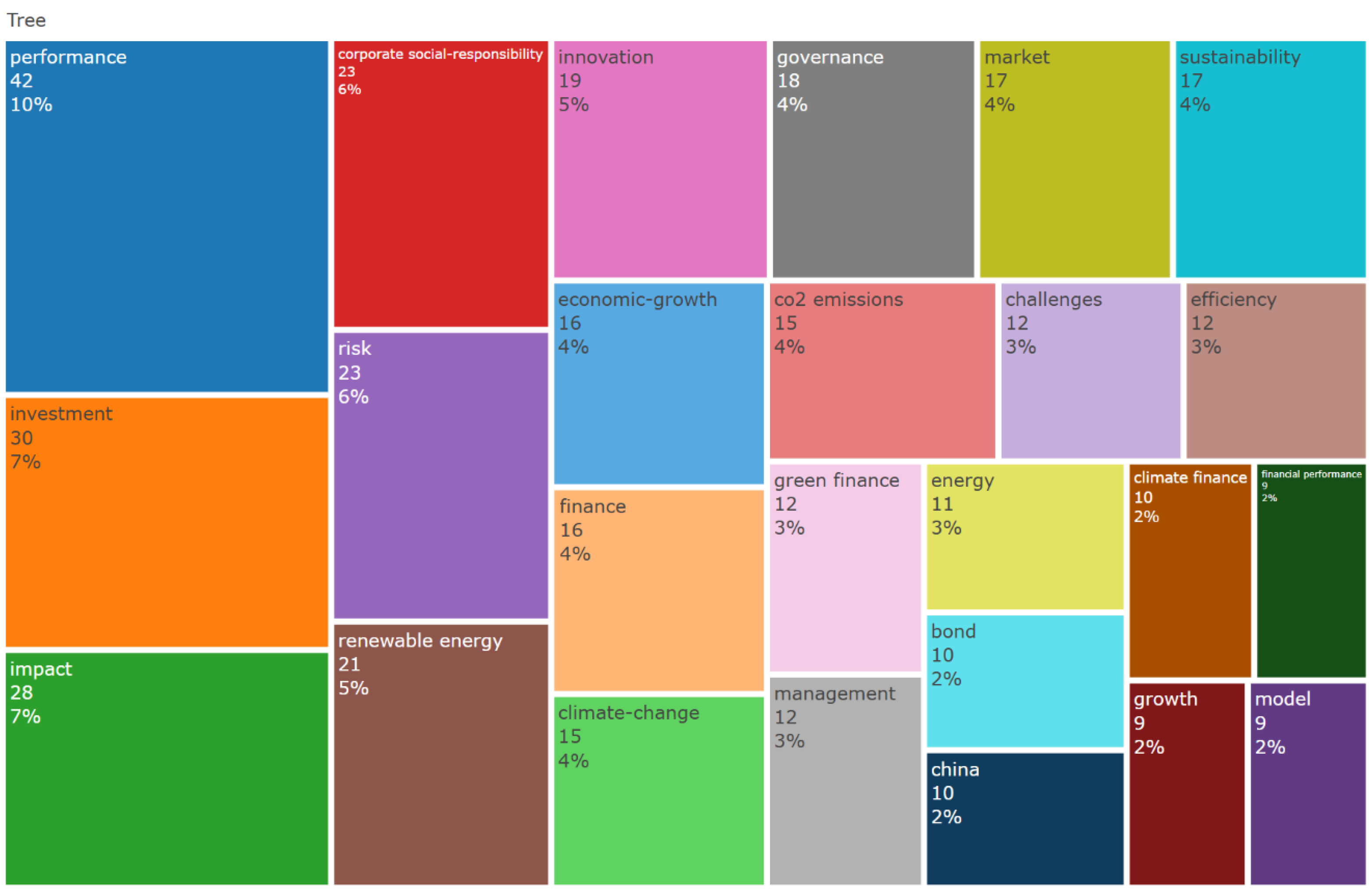

5.6. Words Tree Maps

Word tree maps are a visual tool for bibliometric analysis that shows the frequency and associations of terms or keywords in a huge collection of academic literature. By using larger font sizes and a hierarchical arrangement, these maps draw attention to the most frequently used words and explain how they are conceptually related.

Figure 6 shows the results of a word tree map analysis. There are 42 occurrences of the term “performance” (10% of the total), 30 occurrences of “investment” (7% of the total), 28 occurrences of “Impact” (7% of the total), 23 occurrences of “risk” (6% of the total), 23 occurrences of “corporate social responsibility” (6% of the total), 19 occurrences of “innovation” (5% of the total), 18 occurrences of “governance” (4% of the total), 16 occurrences of “economic-growth” (4% of the total), 17 occurrences of keyword “sustainability” (4% of the total) and so on. Performance, investment, impact and innovation are essential components of impact investing and sustainable finance, facilitating the alignment of financial returns with quantifiable social and environmental outcomes. Integrating CSR principles fosters responsible investment strategies that mitigate risks and promote long-term sustainability (

Bofinger et al., 2022).

5.7. Most Globally Cited Documents

Studying the seminal works on impact investing and sustainable finance provides a solid basis for further research. Highly cited articles provide foundational information relevant to the theme within the field of study (

Talukder, 2024).

Table 6 represents the 10 most globally cited documents. The table shows that the article titled “

Corporate Green Bonds” by Caroline Flammer got the highest citation count of 737 (

Flammer, 2021). The findings indicate that green bonds are gaining popularity among investors. Companies can demonstrate their commitment to the environment by issuing these bonds (

Flammer, 2021). Another highly referenced work, titled “

Responsible Investing: The ESG-Efficient Frontier,” authored by Lasse Heje Pedersen et al., has received 611 citations (

Pedersen et al., 2021). By integrating multiple massive datasets, the authors demonstrated the pros and cons of responsible investing and calculate the empirical ESG-efficient frontier (

Pedersen et al., 2021). Another highly cited document, authored by Ľuboš Pástor et al., titled “

Sustainable Investing in Equilibrium,” has garnered 580 citations (

Pástor et al., 2021). The study revealed that green assets have low anticipated returns in equilibrium because investors like them and they hedge climate risk. Positive shocks to the ESG factor, which measures customer and investor preferences for green products and holdings, make green assets outperform. Another top cited article titled “

Past, present, and future of sustainable finance: insights from big data analytics through machine learning of scholarly research” by

Kumar et al. (

2022) received 225 citations. The research delineates seven key topics in sustainable finance and advocates for the advancement of the sector via innovation, enhanced sustainability practices, cohesive policies, the mitigation of greenwashing, insights from behavioral finance, and the application of emerging technologies such as AI and blockchain (

Kumar et al., 2022). Another top cited research indicates that investors in impact venture capital funds are willing to accept reduced financial returns in exchange for non-financial advantages. Willingness-to-pay models indicate that investors are amenable to lower expected returns, particularly within mission-driven organizations, public pensions, European investors, and PRI signatories. Conversely, entities subject to legal constraints exhibit a diminished willingness to sacrifice returns for social impact (

Barber et al., 2021). Moreover, green bond financing is extensively advocated to advance the Sustainable Development Goals; nevertheless, its tangible influence remains ambiguous. Empirical investigation using prominent sustainability indices indicates that green bonds may exert incremental adverse consequences on environmental and social outcomes, underscoring the necessity for more robust legislative frameworks to augment their efficacy (

Sinha et al., 2021). Recent empirical studies have commenced investigating the connection between investor interest and the success of the green bond market. A study utilizing daily data from green bond indexes reveals that investor attention substantially affects both returns and volatility in the green bond market, albeit with a time-varying impact. These findings are especially pertinent due to the rapid expansion of the green bond market and highlight the essential function of information and investor attention in directing financial resources toward sustainable initiatives (

Pham & Huynh, 2020). Another top cited study indicates that investor attention affects green bond performance, while the broader literature underscores the need of incorporating ESG issues into conventional investment practices. Instead of regarding ESG as a peripheral concept, experts contend it ought to be perceived as an intangible asset that contributes to long-term value, akin to innovation or corporate culture, so strengthening the notion that sustainable investing equates to wise investing (

Edmans, 2023). Recent studies on the advancement of green finance in Hong Kong underscore the collaborative role of national policy and market-oriented strategies in promoting sustainability. The paper, through case analyses of publicly traded companies, demonstrates diverse implementation of sustainable accounting and green bond practices, suggesting a framework in which policy and market dynamics strengthen a resilient green financing system (

Ng, 2018). Another top cited study underscores the increasing convergence of Fintech and sustainable finance, highlighting Fintech’s capacity to facilitate green finance and improve sustainability within financial services. The report demonstrates, via case studies and literature review, that Fintech projects such as Clarity AI and Pensumo aid in identifying greenwashing and enhancing transparency, with regulation being pivotal in safeguarding consumer interests and encouraging responsible innovation (

Vergara & Agudo, 2021). Most of the research focused on ESG, sustainable finance, and impact investment, with authors attempting to demonstrate how innovative financial solutions may have positive impacts on the world.

Table 7. shows the most globally cited documents.

The ten most-cited articles in impact investing and sustainable finance offer essential direction for policy formulation by emphasizing the necessity for standardized ESG frameworks, stricter regulations to address greenwashing, and enhanced disclosure procedures to boost transparency and accountability. For investment strategies, these studies show that people are ready to give up some returns in exchange for effect. This means that people want products that help them meet both their financial and environmental goals. Understanding behavioral finance and the role of Fintech and other new technologies can also help make green financial tools that are more open and use technology. Academic research and disclosures support integrated models that connect financial and social consequences. They underscore the significance of methodological variety and curriculum revisions to align with the changing relevance of ESG and sustainability in finance.

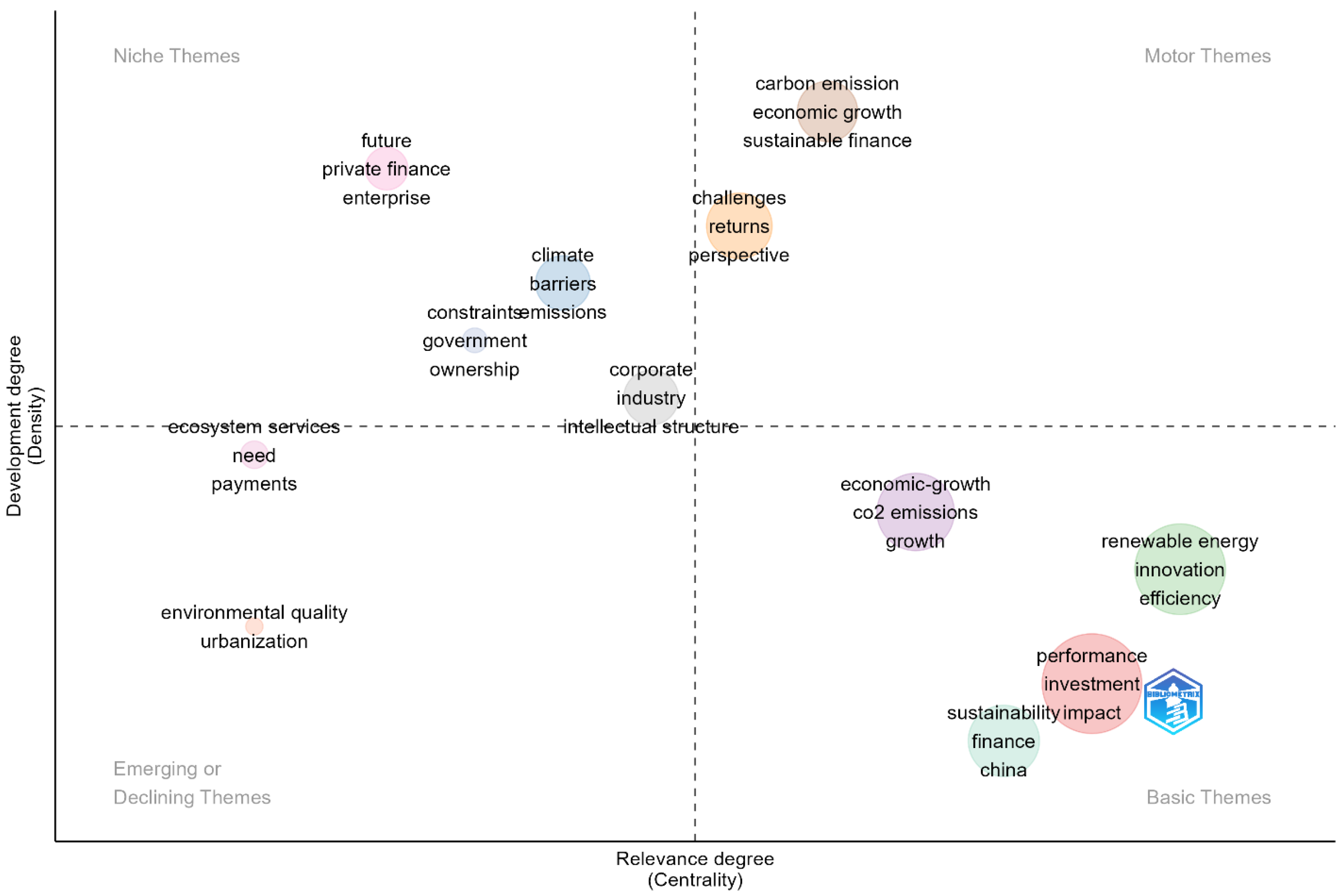

5.8. Analysis of the Thematic Map

The Biblioshiny package in Bibliomatrix-R generates a thematic Map (

Figure 7) including four quadrants, each representing a distinct category: basic themes, motor themes, niche themes, and emerging or declining topics. The themes presented on this map can be divided into concentric clusters based on their relative importance (Centrality) and level of development (Density). In the generation of thematic maps, we established a threshold of a minimum of 5 occurrences for keywords, determined through multiple trials to achieve an optimal balance between network density and interpretability. Lower thresholds resulted in a fragmented structure characterized by numerous peripheral themes, whereas higher thresholds restricted the map to the most dominant topics, potentially neglecting emerging areas like

future enterprises in sustainable finance. This indicates that the arrangement of thematic clusters is partially influenced by parameter settings: stricter thresholds highlight established research domains (e.g., ESG disclosure, green bonds), while more inclusive thresholds reveal emerging but underexplored themes. The hot topics of carbon emission, economic growth, sustainable finance, challenges and return are highlighted in the motor theme. These keywords signify an extremely strong relationship with the underlying research field, presumably pertaining to sustainability, climate change, and energy economics. Their increased importance indicates that they are essential for comprehending and advancing research in fields such as sustainable finance, impact investing, or environmental economics. Economic growth is an essential goal for countries and policymakers, whereas CO

2 emissions and renewable energy play pivotal roles in attaining sustainability and fulfilling global climate commitments, such as those outlined in the Paris Agreement (

Zimon et al., 2022). Their presence in the motor theme signifies that they are not only thoroughly studied but also shape policy formulation, affect investment choices, and contribute to the creation of green financial instruments such as carbon credits and renewable energy bonds.

The keywords in the basic theme quadrant signify essential yet developing domains in sustainable finance and impact investing. Performance, impact, and investment underscore the significance of corporate social responsibility in evaluating performance and results. Innovation, renewable energy, and efficiency underscore the necessity for innovative techniques and structured solutions to overcome obstacles in the domain.

The keywords ecosystem services, environmental quality, and urbanization are in the emerging theme signify the growing interest in impact investment and sustainable finance literature. This indicates how financial mechanisms might assist entrepreneurship, industry and organizations in achieving sustainable business practices. These themes suggest possible advancements in finance methods-like fintech and entrepreneurial ecosystems that correspond with sustainability goals.

The niche topic denotes specialized yet isolated study domains with minimal integration into the wider field. The terms (private finance, enterprise) denote study focused on the conservation of natural ecosystems and biodiversity by private finance and enterprise, which are fundamental to sustainable development.

Emerging themes indicate opportunities to explore innovative financial mechanisms, including green fintech solutions and entrepreneurial ecosystems, that can facilitate sustainable business practices. Additionally, niche themes highlight underexplored areas, such as private finance for ecosystem conservation, which could be more effectively integrated into mainstream sustainable finance research to improve their relevance and impact. Motor themes highlight the necessity for specific policies regarding CO2 reduction, financing for renewable energy, and incentives for sustainable investment. Simultaneously, basic and emerging themes highlight the necessity of fostering innovation, enhancing efficiency, and prioritizing impact-oriented investments to facilitate the attainment of sustainable development goals and overarching environmental and economic objectives.To enhance the effectiveness of research and policy, it is essential to link niche and emerging themes with established motor themes. This integration ensures that specialized studies inform broader strategies, directing the creation of effective financial instruments and comprehensive sustainability frameworks.

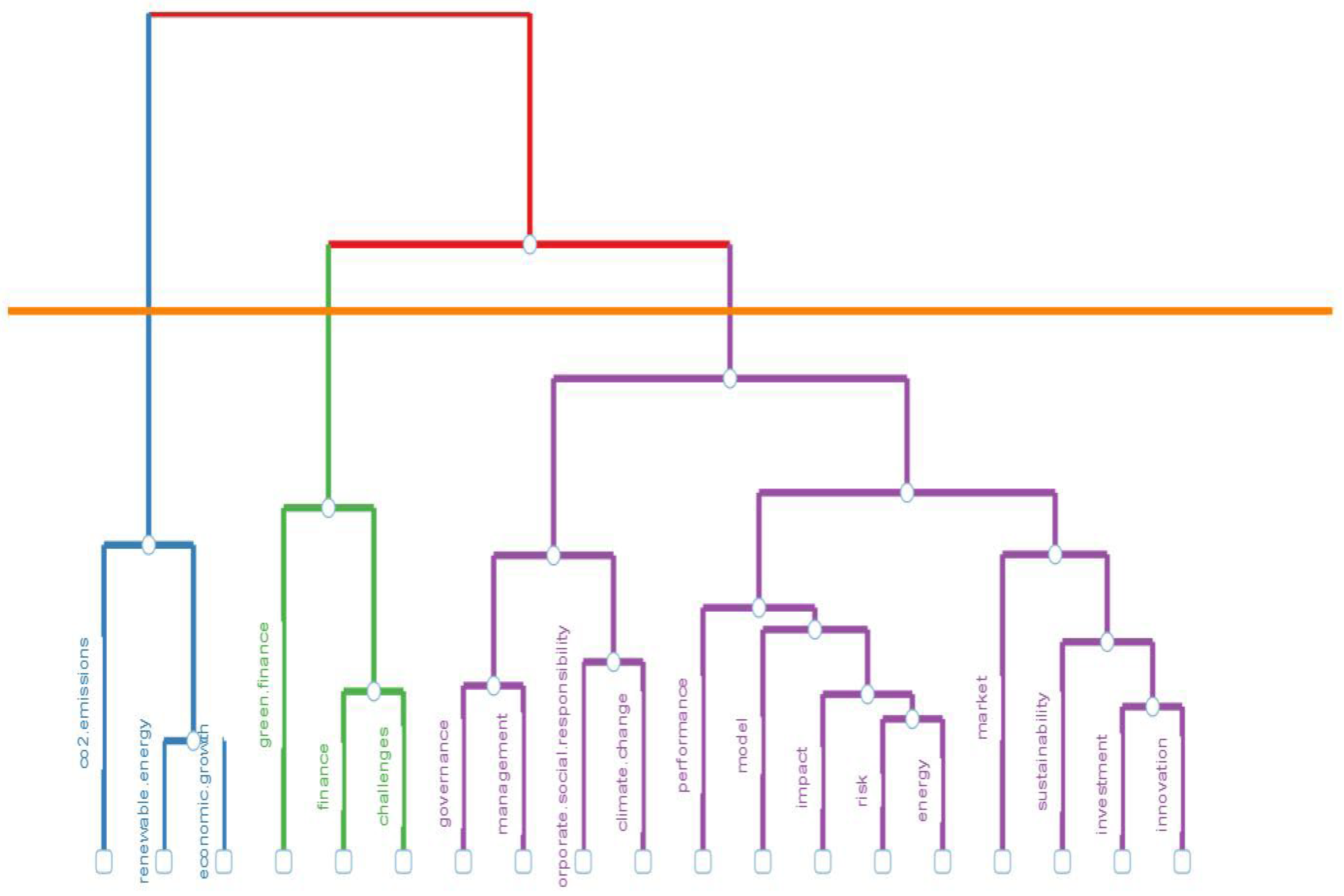

5.9. Topics Dentogram

The topic dendrogram is the visual representation of the word map; it provides information about the position, hierarchy, and level of each study topic (

Havemann et al., 2012;

Vijay Kumar & Senthil Kumar, 2023). Moreover, the topic dendrogram exhibits the hierarchical order and link between keyword groupings obtained by hierarchical clustering. Multiple correspondence analysis was performed, and keywords plus were chosen.three main topics emerge from the keyword plus-based topic dendrogram.

Figure 8 illustrates the dendrogram of the research domain encompassing impact investment and sustainable finance topics divided into three primary clusters. The color blue is used to depict the first topic. It looks at how investments and financial plans that focus on social and environmental impact help businesses come up with new ideas and grow in the long run. The theme could be about figuring out what makes impact investments work, how sustainable finance models encourage innovative concepts, and how responsible, impact-focused investments help the economy for the sustainable economic growth. The second theme in the dendrogram relates to two interrelated fields closely associated with “impact investing” and “sustainable finance”. The initial sub-theme, encompassing keywords like green finance, finance, and challenges, examines the financial and analytical dimensions of impact investing, examining market dynamics, investment frameworks, performance assessment, and risk management to attain both financial returns and identifiable social or environmental outputs. The second sub-theme, incorporating terms such as “performance”, “sustainability”, climate change, engegy, “corporate social responsibility”, “governance”, “impact”, risk, investemnt, model, market, innovation and “management”, underscores the significance of corporate sustainability and governance in promoting responsible investment. It examines how companies synchronize their operations with sustainability objectives via public disclosures, social responsibility activities, and governance structures, thereby affecting their performance and impact over time. Collectively, these sub-themes emphasize the dual objectives of impact investment and sustainable finance: enhancing financial returns while tackling significant social and environmental issues (

Soler-Domínguez et al., 2021).

The dendrogram identifies knowledge gaps on the potential benefits of impact investing models to maximize long-term financial, social, and environmental benefits. There is also a lack of research on the integration of corporate governance, sustainability measurements, and financial frameworks, especially in emerging economies. Policymakers should encourage green finance, renewable energy, and ethical governance alongside impact-oriented financial strategies and corporate sustainability activities. To ensure sustainable finance supports economic growth and climate goals, policies should combine innovation with tangible social and environmental benefits.

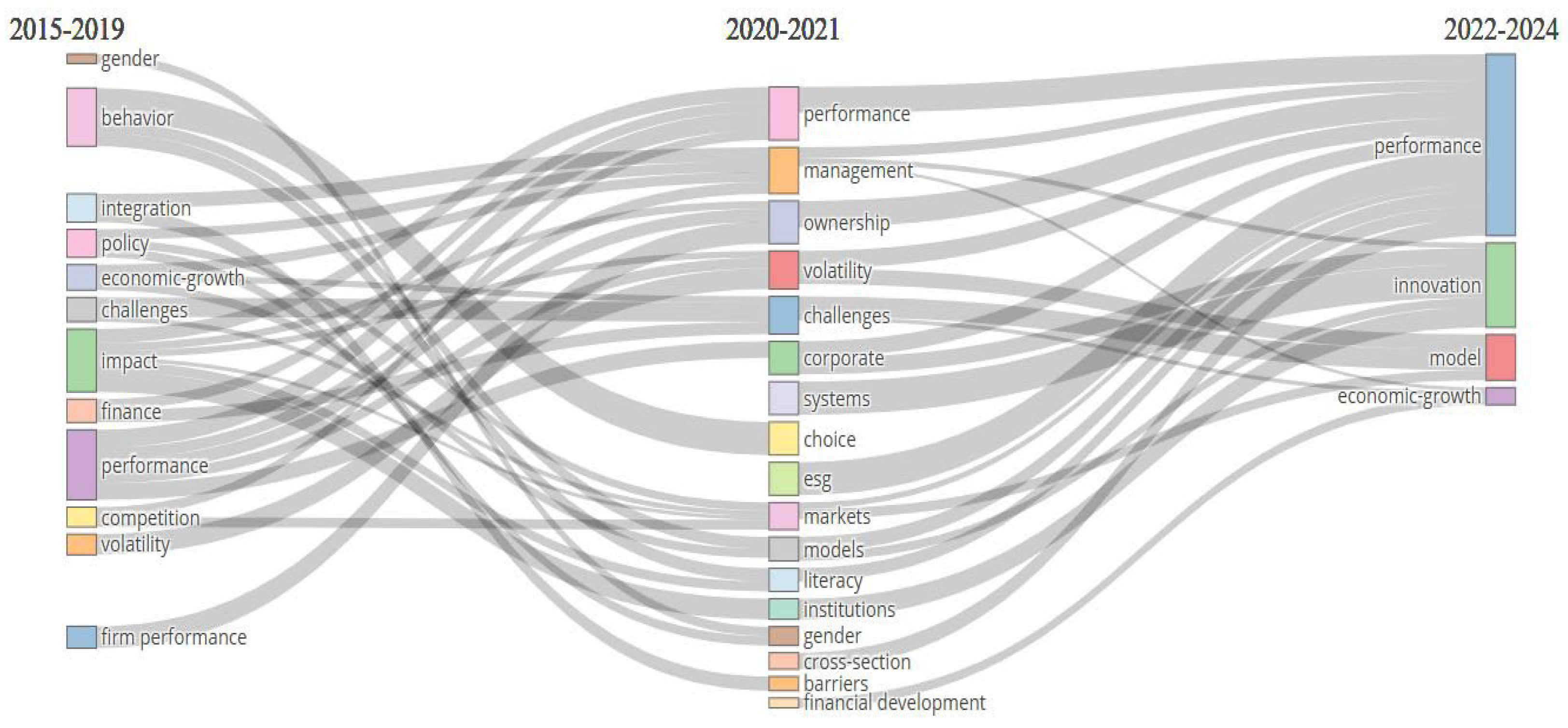

5.10. Thematic Evolution Analysis

Figure 9 illustrates an evolution of themes divided into three distinct periods. During the initial two periods, from 2015 to 2019 and from 2020 to 2021, the most common topics in the articles included ‘Gender’, ‘challenges’, ‘firm performance’, and ‘volatility’. The hot topics that emerged in 2020–2021 included ‘ESG’, ‘financial development’, ‘markets’, ‘corporates’, and ‘institutions. The most recent themes spanning from 2022 to 2024 include ‘innovation’ and ‘economic growth.’

5.11. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

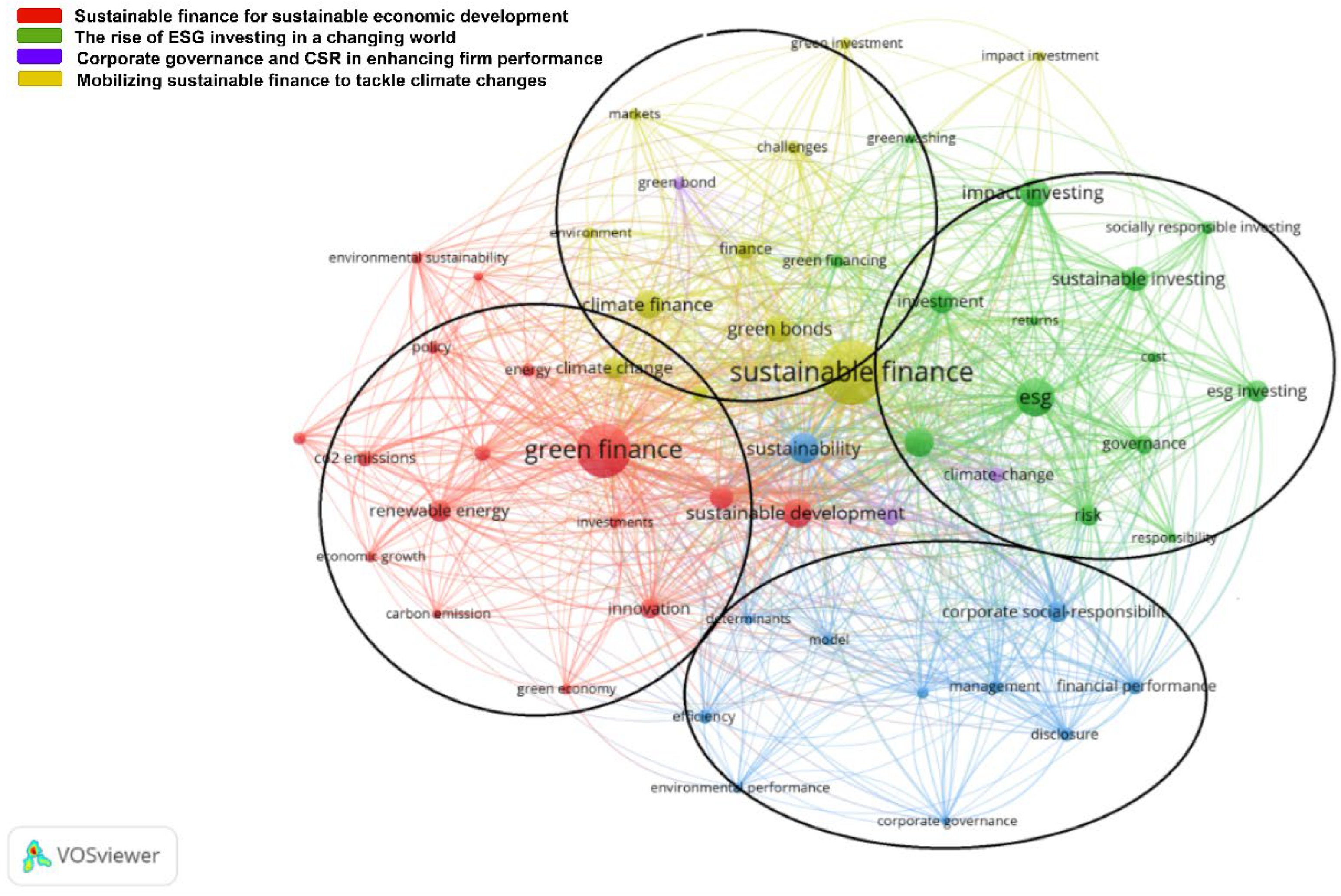

Co-word analysis is a form of content analysis that uses the words included in published literature to establish connections and construct the conceptual framework of a certain topic (

Talukder & Lakner, 2023). The strategy relies on the concept that a significant frequency of recurrence for a specific term in a text indicates a strong correlation between the ideas represented by those keywords. Co-word analysis constructs a network of themes and relationships to visually represent the conceptual space of a field. In order to gain a deeper comprehension of the conceptual framework of the subject, one could utilize this semantic map (

Börner et al., 2003). We used VOSviewer with a minimum threshold of 30 occurrences for keyword co-occurrence analysis. This limit was chosen to include just the most frequently used and conceptually significant terms in the network, improving co-occurrence structure clarity and stability. Lower thresholds yielded fragmented maps with many peripheral terms, whereas higher thresholds risked excluding significant but growing concepts. The threshold of 30 allowed us to cover key topics like sustainable finance, impact investing, ESG disclosure, and green bonds while balancing interpretative depth and analytical rigor. However, changing the threshold might change the map’s structure: more inclusive settings may highlight rising but less established themes (e.g., fintech in sustainable finance), while higher cutoffs favor mature and well-researched domains. A total of 50 keywords attained the threshold after removing country names and variations of the same keywords in singular and plural forms.

Table 8 illustrates the 20 most significant keywords identified in the co-occurrence analysis. The term “sustainable finance” appears most frequently, with 183 occurrences and a total link strength of 512. It is followed by “green finance” with 132 occurrences and a total link strength of 355, “ESG” with 73 occurrences and a total link strength of 217, and “sustainability” with 50 occurrences and a total link strength of 179.

Figure 10 is a keyword co-occurrence map that shows how different themes in the research on impact investing and sustainable finance are prioritized. A larger node indicates more frequent use of the keyword, and the size of the node symbolizes the term’s usage frequency. The thickness of the line connecting two words indicates the strength of the correlation.

Figure 10 also shows the results of the co-occurrences analysis, which show that the terms sustainable finance, green finance, performance, impact, environmental social and governance (ESG), risk, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and impact investing all have bigger nodes on the map. There is a direct line between sustainable development and impact investing. The persistence of this finding in the literature may have a reasonable explanation.

Figure 10 also shows that the term “sustainability” is used precisely because it is undoubtedly a major concern in impact investing (

F. Cunha et al., 2020). Importantly, sustainable finance and impact investing primarily aim towards sustainable development (

Faradynawati & Söderberg, 2022). What this means is that sustainable development is possible with the help of robust sustainable financing solutions. Inseparable links between sustainable development and impact investing, sustainable finance, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, climate change, and green bonds were found in the research. As shown in

Table 9, the researchers grouped the research themes of impact investing and sustainable finance into four clusters.

5.12. Sustainable Finance for Sustainable Economic Development

Sustainable finance integrates environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into financial decision-making and is increasingly acknowledged as a crucial factor in promoting sustainable economic development. Research indicates a significant positive correlation between sustainable finance models and the attainment of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially in the domains of social, environmental, and economic sustainability, as evidenced in OECD and EU countries (

Joshipura et al., 2024;

Ziolo et al., 2021). Green finance, as a component of sustainable finance, has demonstrated its capacity to mitigate pollution, foster technological innovation, and facilitate renewable energy initiatives, thereby contributing to sustainable development, particularly in emerging economies and developing nations (

Ma et al., 2023;

Tosatto et al., 2019). The effectiveness of sustainable finance is contingent upon factors including regulatory frameworks, market maturity, and institutional capacity (

Raman et al., 2024). Developing nations frequently encounter obstacles such as higher transaction costs and inadequate institutional support. Innovations including green fintech, social impact bonds, and advanced risk models are essential for addressing these barriers and facilitating capital mobilization for sustainability projects (

Fu et al., 2023). Sustainable finance can promote economic growth and environmental protection both directly and indirectly; however, its effects are context dependent. There is a necessity for enhanced classification standards, evaluation systems, and information disclosure to optimize its advantages (

Wang et al., 2022). Policymakers should align financial incentives with sustainable outcomes, promote transparency, and facilitate cross-sector partnerships to enhance the integration of sustainable finance into mainstream economic development (

Raman et al., 2024). Sustainable finance, while promising, is not a panacea; it necessitates coordinated global efforts, strong policy backing, and continuous innovation to fully achieve its potential for sustainable economic development. This theme corresponds with the

Capital Theory Approach to Sustainability, which underscores the importance of preserving and enhancing natural, social, human, and financial capital as a basis for sustainable development (

Stern, 1997). This aligns with the principles of

Sustainable Development Theory (Brundtland, 1987), which promotes fulfilling present needs while ensuring the well-being of future generations is not endangered (

Findlay-Brooks, 1985). This cluster’s literature often highlights the significance of financial instruments, including green bonds, climate funds, and ESG-aligned investments, in meeting development priorities, especially those related to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

5.13. The Rise of ESG Investing in a Changing World

The emergence of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) investing indicates a notable transformation in the financial sector, propelled by increasing recognition of climate change, social responsibility, and corporate governance concerns. ESG investing incorporates non-financial factors into investment decisions to achieve financial returns alongside positive societal impact, and it has gained significant traction among both institutional and individual investors (

Zhong, 2023). Research indicates that ESG factors offer significant insights into firm fundamentals and risk (

Pedersen et al., 2021). Portfolios developed with ESG considerations can attain competitive, and at times superior, risk-adjusted returns, particularly over extended periods and during market crises (

Bagh et al., 2024). The field encounters challenges, notably the absence of standardization in ESG definitions and reporting, which complicates the measurement of impact and comparison across investments (

Buniakova & Zavyalova, 2021). Critics argue that ESG investing can function as a mechanism for profit or reputation rather than authentic ethical transformation, and that it may inadequately tackle systemic challenges such as climate change or inequality, particularly when corporate governance frameworks prioritize shareholder value (

Leins, 2020;

Macey, 2021). Despite these criticisms, ESG investing is experiencing growth, in part due to a perceived inadequacy of government responses to significant social and environmental issues, prompting investors to seek solutions within the private sector. The outlook for ESG investing is favorable, characterized by rising demand for sustainable investments and an expanding acknowledgment of the significance of incorporating ESG factors into risk management and long-term value creation. The ESG framework aligns with the

Triple Bottom Line Theory (

Elkington, 1998), emphasizing the need to balance financial returns, social justice, and ecological protection. Institutional Theory elucidates the legitimacy of ESG investing through regulatory frameworks, sustainability reporting standards (e.g., TCFD, GRI), and market pressures, leading to the extensive dissemination of ESG principles (

Willmott, 2015).

Corporate Sustainability Theory emphasizes the integration of ESG concerns into core business strategies to improve transparency, reduce risks, and attract socially responsible investors (

Kantabutra & Ketprapakorn, 2020). This cluster highlights the transition of ESG investing from a niche strategy to a mainstream framework, influencing capital markets considering systemic global changes.

5.14. Corporate Governance and CSR in Enhancing Firm Performance

Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) are increasingly acknowledged as essential factors influencing firm performance, particularly in the contexts of sustainable finance and impact investment. Effective corporate governance, marked by competent boards, independent oversight, and committees focused on sustainability, can improve a firm’s sustainability performance and investment efficiency, thereby enhancing firm value (

Azevedo et al., 2022;

Rashid & Kabir, 2025) Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives, especially those targeting social issues, have demonstrated a positive impact on investment decisions and financial performance, reinforcing the notion that responsible business practices can be consistent with shareholder interests and stakeholder expectations (

Nandi et al., 2025;

Waheed et al., 2021). The relationship is complex: although strong governance and corporate social responsibility typically associated with improved financial and sustainability results, the effects may differ based on variables such as the firm’s investment horizon, the characteristics of institutional investors, and the particular governance mechanisms implemented. Research indicates that the social dimension of corporate social responsibility (CSR) exerts a more significant influence on performance compared to environmental or governance factors, and that the role of CSR expenditure as a mediator is constrained (

Azevedo et al., 2022;

Rashid & Kabir, 2025). In the realm of sustainable finance and impact investing, these findings indicate that investors are placing greater importance on firms that exhibit transparent and accountable governance, along with genuine CSR commitments, as these factors are associated with diminished risk, enhanced efficiency, and the creation of long-term value (

Singhania et al., 2024a). Inconsistencies in ESG ratings and the potential for superficial or “greenwashed” CSR initiatives present ongoing challenges, highlighting the necessity for standardized metrics and authentic integration of sustainability within corporate strategy of their implementation and the wider regulatory and market environment. (

Coelho et al., 2023;

Rashid & Kabir, 2025). The

Triple Bottom Line Theory advocates for a comprehensive assessment of economic, social, and environmental returns, which aligns with the objectives of sustainable finance in creating integrated value (

Elkington, 1998).

Institutional Theory elucidates the influence of regulatory frameworks, industry standards, and normative pressures on firms, prompting the adoption of robust governance and CSR practices that enhance legitimacy and trust among stakeholders in sustainable finance (

Willmott, 2015). Theoretical perspectives highlight that robust corporate governance and corporate social responsibility are crucial for promoting impact investing and sustainable finance, enhancing firm performance and supporting wider sustainability objectives. In summary, corporate governance and CSR can improve firm performance and draw sustainable, impact-oriented capital; however, their effectiveness is contingent upon thoroughness.

5.15. Mobilizing Sustainable Finance to Tackle Climate Changes

Mobilizing sustainable finance is crucial for addressing climate change, as it directs capital to projects and technologies that mitigate emissions and facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy. Green finance instruments, including green bonds, loans, and impact investing, have experienced significant growth, facilitating substantial investments in renewable energy, sustainable infrastructure, and resource efficiency (

Fu et al., 2023;

Zhang et al., 2022). Impact investing specifically aims for quantifiable environmental results in conjunction with financial gains, proving efficacy in driving companies to reduce carbon emissions, particularly when investors anticipate stricter climate regulations and advancements in technology (

De Angelis et al., 2023;

Pástor et al., 2021). Empirical evidence indicates that green finance effectively reduces ecological footprints and CO

2 emissions, particularly when integrated with policy support and technological innovation (

Fu et al., 2023;

Khan et al., 2022;

Zhang et al., 2022). The effectiveness of sustainable finance is constrained by challenges including the limited proportion of green investors, the absence of standardized metrics, and the potential for greenwashing, which may compromise credibility and impact (

F. A. F. d. S. Cunha et al., 2021;

De Angelis et al., 2023;

Kölbel et al., 2020). Sustainable finance has the capacity to direct capital towards environmentally responsible firms and promotes improved corporate practices (

Jaya, 2024;

Kölbel et al., 2020). However, its transformative potential is dependent upon the establishment of strong regulatory frameworks, transparent reporting mechanisms, and collaboration among governments, financial institutions, and businesses (

Eyo-Udo et al., 2024;

Fu et al., 2023;

Jaya, 2024;

Kölbel et al., 2020). Sustainable finance and impact investing serve as effective mechanisms for climate action; however, their efficacy in meeting global climate objectives necessitates systemic reforms, policy coherence, and a dedication to measurable, real-world results (

De Angelis et al., 2023;

Fu et al., 2023). This theme is fundamentally based on the

Capital Theory Approach, which emphasizes the protection of natural capital as an essential resource for sustainable economic growth (

Stern, 1997). Sustainable finance serves as a vital mechanism for directing investments towards innovative, low-carbon technologies and resilient infrastructure, in accordance with the principles of

Sustainable Development Theory, which emphasize fulfilling present needs without jeopardizing future generations (

Findlay-Brooks, 1985). The changing dynamics of climate finance are influenced by

Institutional Theory, where policy frameworks, international agreements, and industry standards impose significant normative and coercive pressures, guiding both public and private entities toward more sustainable practices (

Willmott, 2015). These perspectives demonstrate that sustainable finance functions not only as a funding mechanism but also as a dynamic catalyst for climate action and economic transformation.

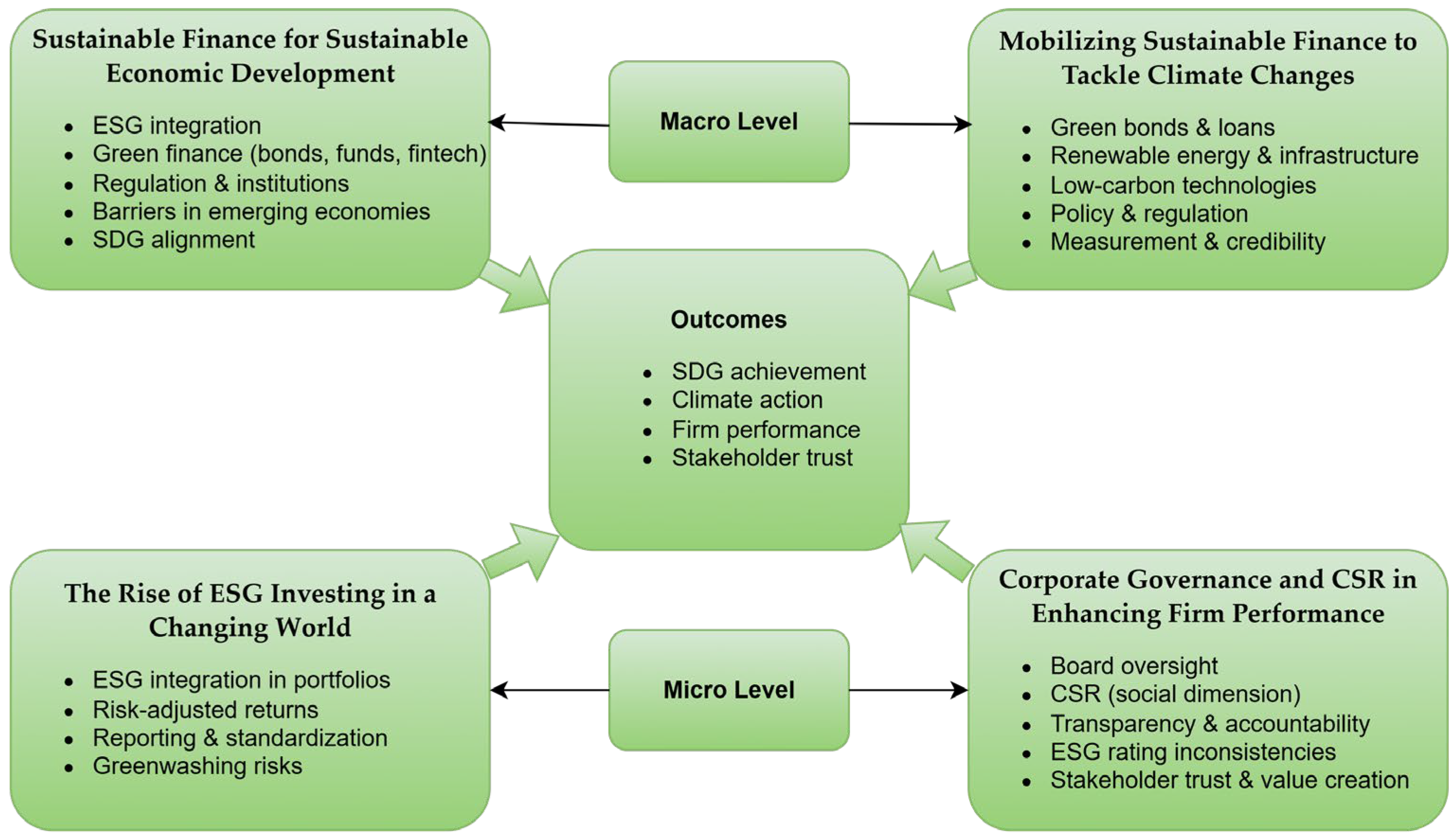

The bibliometric patterns identified within the four thematic clusters can be thoroughly analyzed using established theoretical frameworks. The very first cluster,

sustainable finance for sustainable economic development, is closely aligned with Stakeholder Theory, highlighting the need to balance the interests of investors, society, and the environment to foster holistic economic growth. The second cluster,

the emergence of ESG investing in a dynamic environment, embodies the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) perspective, emphasizing the incorporation of environmental, social, and financial performance in investment choices. The third cluster, focusing on

corporate governance and CSR in improving firm performance, aligns with Stakeholder Theory and Institutional Theory, illustrating how firms implement governance practices and socially responsible initiatives to fulfill stakeholder expectations and achieve legitimacy within institutional contexts. The fourth cluster focuses on

mobilizing sustainable finance to address climate change, utilizing Institutional Theory and Stakeholder Theory. It demonstrates how regulatory policies, market mechanisms, and stakeholder pressures influence the distribution of sustainable financial resources for environmental challenges. Theoretical connections indicate that impact investing and sustainable finance are influenced by empirical trends and are supported by coherent theoretical frameworks, which elucidate the research focus and emerging patterns in literature. The conceptual framework of impact investing and sustainable finance is depicted in

Figure 11.

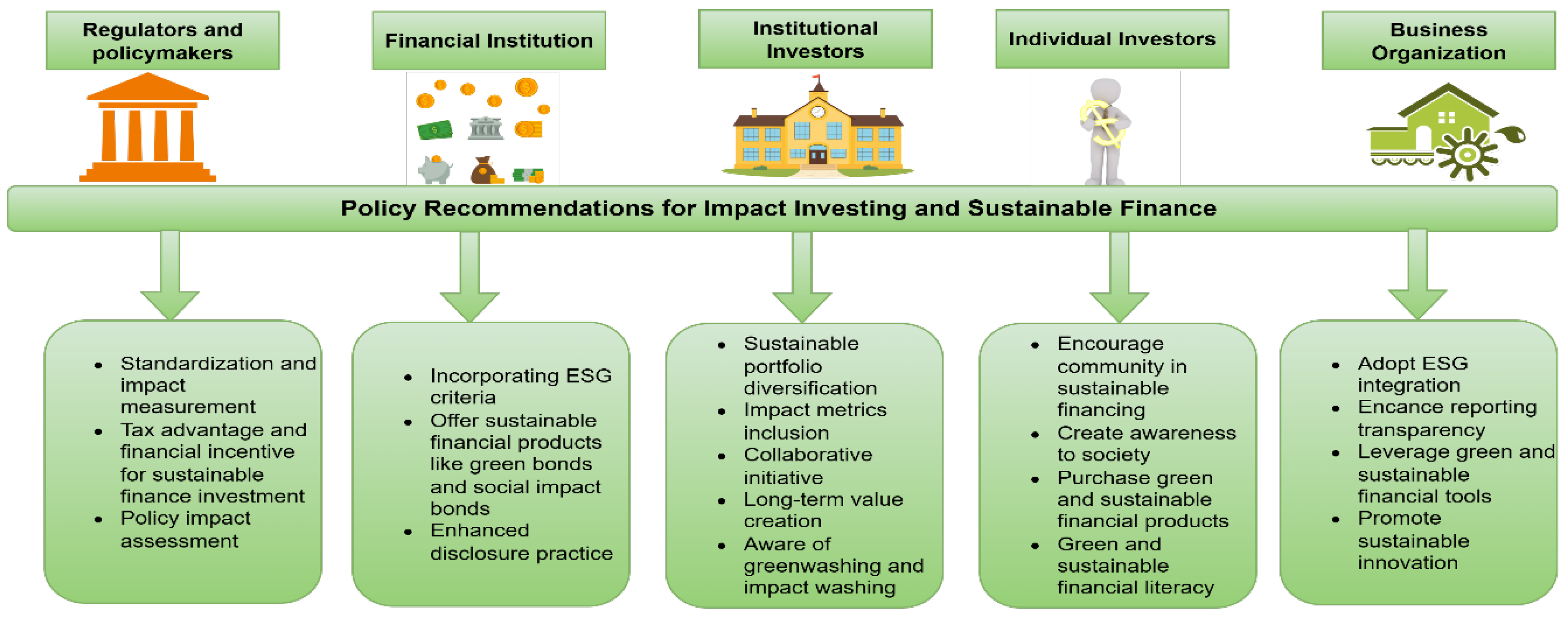

6. Conclusion, Implications, Future Research Directions and Limitations

The bibliometric analysis of impact investing and sustainable finance demonstrates a significantly growing area marked by a rising academic focus and practical significance. The increase in scholarly papers indicates a growing awareness of the crucial role that these financial innovations play in tackling worldwide social and environmental issues. However, most of the research was undertaken in advanced economies, with European countries being the most productive. The increase in the number of articles indicates a rising concern with linking financial success with beneficial social results, highlighting the significance of incorporating sustainable practice into investment choice. This research reveals several rising trends, including the widespread adoption of innovative financial products such as green bonds, social impact bonds and sustainability linked bonds for the mitigation of climate change. Moreover, they are associated with significant decreases in greenhouse gas emissions and enhanced renewable energy capacity. These financial products are revolutionizing the allocation of capital towards initiatives that have distinct environmental and social advantages. Furthermore, the incorporation of ESG factors into investment frameworks is increasingly common, indicating a move towards more accountable and sustainable investment practices in many developed countries. The research indicates that impact investing and sustainable finance present both opportunities and obstacles, notwithstanding the potential positive results that may arise from these initiatives. Financial institutions and investors should be vigilant of the potential consequences of

greenwashing and

impact washing when making investment decisions. We encourage the idea of policymakers and practitioners working together to foster impact investing and sustainable financing by creating supportive legislation, infrastructure, and resources. Nevertheless, the review revealed the following important participants in the impact investing and sustainable finance landscape. When it comes to impact investing and sustainable financing, regulators-policymakers, financial institutions, Institutional investors, individual investors and business organization all play crucial roles. The authors propose a policy framework, which is shown in

Figure 12, to make impact investing and sustainable finance more effective.

Impact Investing and Sustainable Finance strongly connects with several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by advocating financial solutions that have a positive social and environmental impact. For example, SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) is supported by investments in renewable energy projects such as solar farms in rural regions, which provide clean electricity while lowering carbon emissions. Similarly, SDG 4 (Quality Education) benefits from impact funds that invest in educational technology firms to increase access to marginalized populations. Sustainable finance also contributes to SDG 13 (Climate Action) by supporting green bonds that finance climate-resilient infrastructure. Additionally, SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) is encouraged through microfinance initiatives that help small companies grow in underdeveloped countries.

For professionals, the review emphasizes the significance of keeping up to date with evolving trends and advances in the financial industry. Developing and sustaining strong systems for measuring impact and providing clear reports are crucial for improving the trustworthiness and efficiency of impact investments. In summary, the bibliometric evaluation provides a thorough and detailed overview of the present condition of impact investment and sustainable finance. It gives significant insights and will help direct future research and practice in these important fields. The bibliometric review highlights the necessity of progressing research, policy, and practice in impact investing and sustainable finance. Researchers are strongly urged to provide uniform frameworks for measuring impact, investigate the long-term success of impact investments, and examine how rules affect the growth of markets. It is recommended that policymakers build regulatory settings that are favorable of green financial instruments, encourage transparency, and set clear requirements for impact reporting. Practitioners must remain updated on developing trends and implement the most effective methods for measuring impact and integrating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors. This will improve the effectiveness and credibility of their investments. The market is poised for expansion, propelled by a rising need for ethical investing choices, and stakeholders must adjust to changing trends and regulations to optimize their impact on sustainable financial systems. Ensuring transparency and accountability in sustainable finance necessitates standardized ESG reporting, explicit taxonomy, third-party verification, and robust regulatory monitoring. Public access to data, uniform impact measures, and stakeholder participation increase credibility and match financing with genuine goals of sustainability.

Thematic analysis of keyword co-occurrence identifies four primary research streams within the overarching discourse on impact investing and sustainable finance. The theme

Sustainable Finance for Sustainable Economic Development highlights the significance of financial mechanisms in promoting equitable growth, alleviating poverty, and aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The

theme the Rise of ESG Investing in a Changing World illustrates an increasing investor interest in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria, prompting inquiries regarding performance, transparency, and the incentives for socially responsible investing. The theme

Corporate Governance and CSR in Enhancing Firm Performance emphasizes the role of governance frameworks and corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities in influencing firm-level results, including profitability, reputation, and resilience. Finally, the theme

Mobilizing Sustainable Finance to Address Climate Change emphasizes the growing utilization of instruments such as green bonds, fintech, and blended finance to facilitate climate mitigation and adaptation. Collectively, these topics establish a robust basis for future research that connects financial innovation, corporate conduct, and sustainability objectives in both established and emerging countries.

Table 10 presents the future research directions and potential research questions in the research domain of impact investing and sustainable finance.