Environmental Certifications as Strategic Assets? Evidence from Italian Chemical and Pharmaceutical Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG Disclosure and Business Performance

2.2. Research Gap

2.3. Industry Focus: Chemical and Pharmaceutical Context

3. Data and Methods

3.1. AI-Based Content Analysis

- ➢

- Generic environmental disclosure, such as the presence of a dedicated section specifically addressing environmental reporting, sentences regarding water discharge management practices or statements on adherence to environmental norms, and environmental certifications (Disclosures)

- ➢

- Specific disclosure of environmental certifications formally obtained by the company (Certifications).

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Content Analysis Results

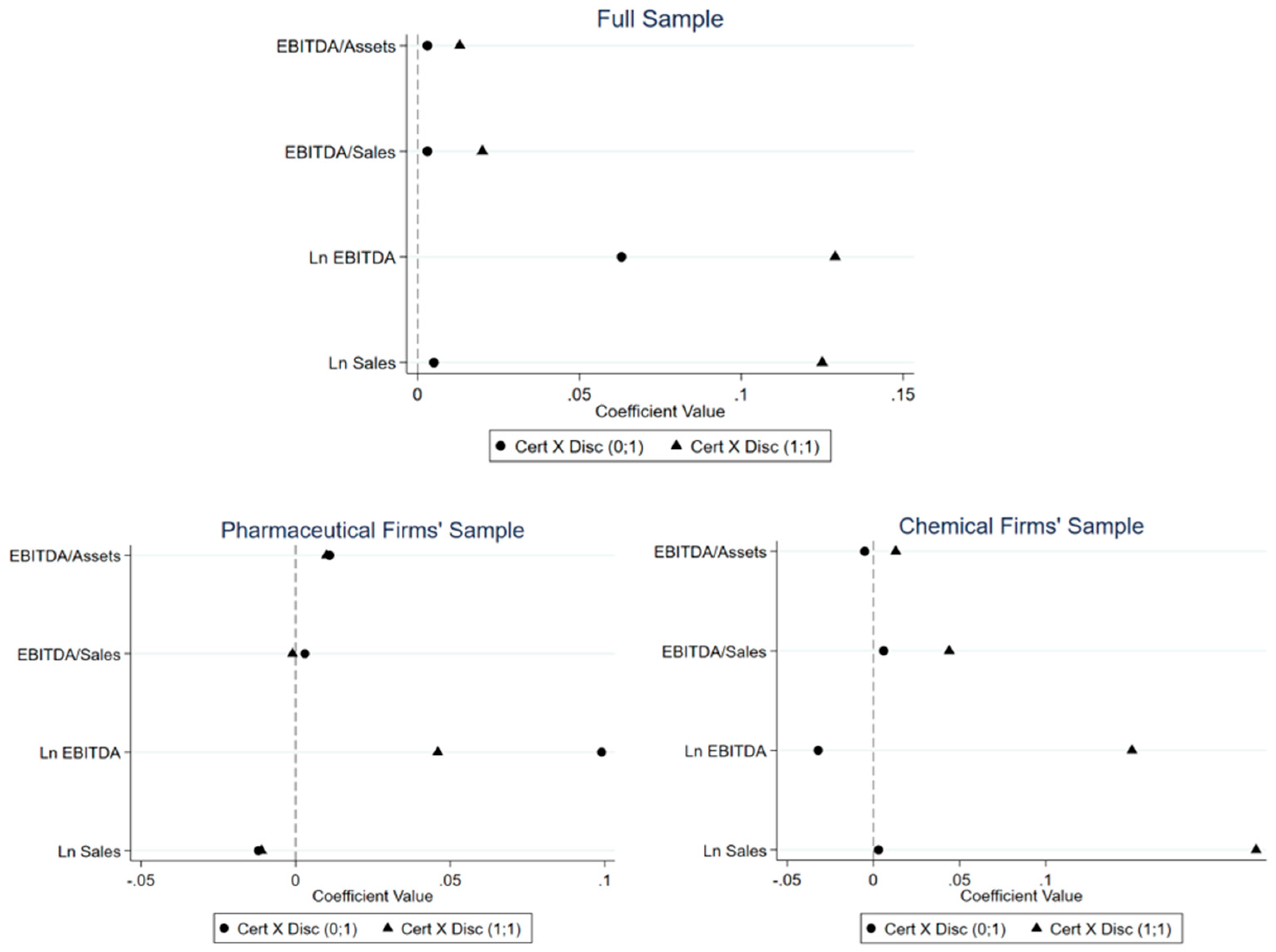

4.2. Multivariate Analyses Results

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2.2. Full Sample

4.2.3. Split Sample

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. AI Content Analysis Pipeline

- an OCR-based text-extraction module, implemented with the Tesseract library, which converts PDF pages (including scanned images within PDFs) into machine-readable text;

- a topic-detection module, which applies a combination of rule-based routines and supervised classifiers to the extracted text in order to identify passages that discuss environmental disclosure, third-party certifications, emissions trading, and related subjects.

Appendix B. Descriptive Statistics by Sector

| Variable | Obs | Mean/Prop. | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Variable Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | 846 | 241,195 | 356,028 | 9825 | 3,696,000 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| Sales | 861 | 261,410 | 474,458 | 0.00 | 5,317,564 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| EBITDA | 860 | 12,831 | 61,035 | −649,664 | 323,484 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| ROE | 847 | 9.67 | 21.94 | −149.25 | 92.86 | Ratio |

| Debt_to_Equity | 849 | 1.56 | 2.04 | 0.00 | 20.45 | Ratio |

| Disclosure | 862 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | Binary |

| Certifications | 862 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | Binary |

| Geograhical_Clusters | 862 | 1.40 | 0.76 | 1 | 4 | Categorical |

| Variable | Obs | Mean/Prop | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Variable Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | 882 | 281,689 | 410,440 | 5,224,772 | 3,635,235 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| Sales | 882 | 239,630 | 321,955 | 0 | 1,796,530 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| EBITDA | 882 | 22,678 | 40,180 | −74,680 | 362,704 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| ROE | 879 | 15.08 | 19.91 | −123.5 | 86.06 | Ratio |

| Debt_to_Equity | 877 | 1.96 | 3.23 | 0.02 | 38.59 | Ratio |

| Disclosure | 882 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | Binary |

| Certifications | 882 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | Binary |

| Geograhical_Clusters | 882 | 1.77 | 0.97 | 1 | 4 | Categorical |

References

- Abbott, W. F., & Monsen, R. J. (1979). On the measurement of corporate social responsibility: Self-reported disclosures as a method of measuring corporate social involvement. Academy of Management Journal, 22(3), 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, R., & Alsayegh, M. F. (2021). Determinants of corporate environment, social and governance (ESG) reporting among Asian firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(4), 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Sidhoum, A., Dakpo, K. H., & Latruffe, L. (2022). Trade-offs between economic, environmental and social sustainability on farms using a latent class frontier efficiency model: Evidence for Spanish crop farms. PLoS ONE, 17(1), e0261190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvidsson, S., & Dumay, J. (2022). Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(3), 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, N., Chimhundu, R., & Chan, K. C. (2022). Dynamic capabilities to achieve corporate sustainability: A roadmap to sustained competitive advantage. Sustainability, 14(3), 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, M. J., Sánchez-Sellero, P., & Ayad, F. (2024). Green is the new black: How research and development and green innovation provide businesses a competitive edge. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(2), 1004–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, E., Bo, S., Petruzzella, F., & Salvi, A. (2025). Greenwashing and sustainability disclosure in the climate change context: The influence of third-party certification on Chinese companies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 34(6), 7851–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhir, L., & Elmeligi, A. (2019). Carbon footprint of the global pharmaceutical industry and relative impact of its major players. Journal of Cleaner Production, 214, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F., Kölbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2022). Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Review of Finance, 26(6), 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIO Intelligence Service. (2013). Study on the environmental risks of medicinal products, final report prepared for executive agency for health and consumers. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/study_environment_0.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Brown, H. S., de Jong, M., & Levy, D. L. (2009). Building institutions based on information disclosure: Lessons from GRI’s sustainability reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(6), 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calciolari, S., Cesarini, M., & Ruberti, M. (2024). Sustainability disclosure in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries: Results from bibliometric analysis and AI-based comparison of financial reports. Journal of Cleaner Production, 447, 141511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K., & Wang, Y. H. (2015). Determinants of social disclosure quality in Taiwan: An application of stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(2), 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cue, B. W., & Zhang, J. (2009). Green process chemistry in the pharmaceutical industry. Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews, 2(4), 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N., Ji, H., Iwata, K., & Arimura, T. H. (2022). Do ESG reporting guidelines and verifications enhance firms’ information disclosure? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(5), 1214–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimes, R., & Molinari, M. (2024). Non-financial reporting and corporate governance: A conceptual framework. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 15(5), 1067–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimson, E., Marsh, P., & Staunton, M. (2020). Divergent ESG Ratings. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 47(1), 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, I. J., & Rodrigo, P. (2018). Why do firms in emerging markets report? A stakeholder theory approach to study the determinants of non-financial disclosure in Latin America. Sustainability, 10(9), 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilbirt, H., & Parket, I. R. (1973). The practice of business: The current status of corporate social responsibility. Business Horizons, 16(4), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C., Jones, S., & Tremblay, M. S. (2024). Greenwashing and sustainability assurance: A review and call for future research. Journal of Accounting Literature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. S., Heravi, S., & Xiao, J. Z. (2005). Determinants of corporate social and environmental reporting in Hong Kong: A research note. Accounting Forum, 29(2), 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, O., Reepmeyer, G., & Von Zedtwitz, M. (2008). Leading pharmaceutical innovation: Trends and drivers for growth in the pharmaceutical industry. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, J. M. (1952). Air Pollution Abatement by the Chemical Industry:—Review and Survey—. American Industrial Hygiene Association Quarterly, 13(2), 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995). Constructing a research database of social and environmental reporting by UK companies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(2), 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervas-Oliver, J. L., Márquez García, J. A. A., & Rojas-Alvarado, R. (2024). Are clusters and industrial districts really driving sustainability innovation? Competitiveness Review. An International Business Journal, 34(5), 896–915. [Google Scholar]

- Inchausti, B. G. (1997). The influence of company characteristics and accounting regulation on information disclosed by Spanish firms. European Accounting Review, 6(1), 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korca, B., Costa, E., & Farneti, F. (2021). From voluntary to mandatory non-financial disclosure following Directive 2014/95/EU: An Italian case study. Accounting in Europe, 18(3), 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmerer, K. (2010). Pharmaceuticals in the environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 35, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajmi, A., & Shiri, D. (2025). The mediating role of green innovation on the relation between environmental regulations and firm performance: Evidence from European context. International Journal of Law and Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinskienė, G., & Tvaronavičienė, M. (2012). Environmental, social and governance performance of companies: The empirical research on their willingness to disclose information. Available online: https://etalpykla.vilniustech.lt/handle/123456789/154396 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Lev, B. (2017). Evaluating sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 29(2), 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, R., Schimperna, F., Paoloni, P., & Galeotti, M. (2021). The climate-related information in the changing EU directive on non-financial reporting and disclosure: First evidence by Italian large companies. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 23(1), 250–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, F., & Orsenigo, L. (2015). The evolution of the pharmaceutical industry. Business History, 57(5), 664–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meznar, M. B., & Nigh, D. (1995). Buffer or bridge? Environmental and organisational determinants of public affairs activities in American firms. Academy of Management Journal, 38(4), 975–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D., & Rondinelli, D. (2002). Adopting corporate environmental management systems: Motivations and results of ISO 14001 and EMAS certification. European Management Journal, 20(2), 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). Saving costs in chemicals management: How the OECD ensures benefits to society. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L. D. (2005). Social and environmental accountability research: A view from the commentary box. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 18(6), 842–860. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L. D. (2011). Twenty-one years of social and environmental accountability research: A coming of age. In Accounting Forum (Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 1–10). [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P., Panday, P., & Dangwal, R. C. (2020). Determinants of environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) disclosure: A study of Indian companies. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 17, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. (1995). The role of corporations in achieving ecological sustainability. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 936–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, T. (2024). Does pharma need patents? The Yale Law Journal, 134, 2038. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, S., & Webster, J. (2021). Perceived greenwashing: The effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 171, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarmuji, I., Maelah, R., & Tarmuji, N. H. (2016). The impact of environmental, social and governance practices (ESG) on economic performance: Evidence from ESG score. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, 7(3), 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J. (2000). Methodological issues-Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 13(5), 667–681. [Google Scholar]

- Venturelli, A., Caputo, F., Leopizzi, R., & Pizzi, S. (2019). The state of art of corporate social disclosure before the introduction of non-financial reporting directive: A cross-country analysis. Social Responsibility Journal, 15(4), 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R. O., & Naser, K. (1995). Firm-specific determinants of the comprehensiveness of mandatory disclosure in the corporate annual reports of firms listed on the stock exchange of Hong Kong. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 14(4), 311–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Chen, L., & Dong, L. (2024). A critical review of climate change mitigation policies in the EU—Based on vertical, horizontal and policy instrument perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 467, 142972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, P. L., & Roth, K. (1999). An empirical analysis of sustained advantage in the US pharmaceutical industry: Impact of firm resources and capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 20(7), 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusifzada, L., Lončarski, I., Czupy, G., & Naffa, H. (2025). Return trade-offs between environmental and social pillars of ESG scores. Research in International Business and Finance, 75, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pharmaceutical Firms | Chemical Firms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Certifications | Disclosure | Certifications | Disclosure |

| 2012 | 0.347 | 0.589 | 0.427 | 0.629 |

| 2013 | 0.426 | 0.585 | 0.429 | 0.615 |

| 2014 | 0.414 | 0.606 | 0.484 | 0.674 |

| 2015 | 0.420 | 0.610 | 0.464 | 0.680 |

| 2016 | 0.394 | 0.586 | 0.479 | 0.698 |

| 2017 | 0.400 | 0.620 | 0.510 | 0.670 |

| 2018 | 0.394 | 0.566 | 0.459 | 0.633 |

| 2019 | 0.439 | 0.643 | 0.470 | 0.670 |

| 2020 | 0.459 | 0.653 | 0.460 | 0.660 |

| average | 0.410 | 0.607 | 0.465 | 0.659 |

| Variable | Obs | Mean/Prop | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Variable Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | 1728 | 261,864 | 385,185 | 9825 | 3,696,000 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| Sales | 1743 | 250,389 | 404,567 | 0 | 5,317,564 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| EBITDA | 1742 | 17,817 | 51,761 | −649,664 | 362,704 | Cont. (EUR th.) |

| ROE | 1726 | 12.43 | 21.10 | −149.25 | 92.86 | Ratio |

| Debt_to_Equity | 1726 | 1.76 | 2.72 | −0.29 | 38.59 | Ratio |

| Disclosure | 1748 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | Binary |

| Certifications | 1748 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | Binary |

| Geographical_Clusters | 1748 | 1.59 | 0.89 | 1 | 4 | Categorical |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Ln Sales | Ln EBITDA | EBITDA/Sales | EBITDA/Assets | ROE |

| Certifications × Disclosure (0;1) | 0.005 | 0.063 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.070 |

| (0.036) | (0.075) | (0.012) | (0.008) | (1.710) | |

| Certifications × Disclosure (1;1) | 0.125 *** | 0.129 | 0.020 | 0.013 | −0.895 |

| (0.036) | (0.080) | (0.012) | (0.009) | (1.736) | |

| Ln_Assets | 0.173 *** | 0.130 * | 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.276 |

| (0.031) | (0.067) | (0.010) | (0.009) | (1.473) | |

| Efficiency | 0.001 *** | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.069 *** | 0.001 |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.004) | (0.023) | |

| Debt_to_Equity | −0.062 *** | 0.039 *** | −0.013 *** | 0.003 ** | 0.151 |

| (0.006) | (0.014) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.266) | |

| Controlled by Sector and Geographical cluster | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 9.862 *** | 7.552 *** | 0.054 | 0.010 | 9.342 |

| (0.369) | (0.800) | (0.125) | (0.106) | (17.600) | |

| Observations | 1710 | 1549 | 1710 | 1711 | 1696 |

| R-squared | 0.085 | 0.012 | 0.029 | 0.195 | 0.000 |

| Number of companies | 198 | 196 | 198 | 198 | 198 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Ln Sales | Ln EBITDA | EBITDA/Sales | EBITDA/Assets | ROE |

| Certifications × Disclosure (0;1) | 0.003 | −0.032 | 0.006 | −0.005 | −0.570 |

| (0.055) | (0.120) | (0.012) | (0.016) | (2.668) | |

| Certifications × Disclosure (1;1) | 0.222 *** | 0.150 | 0.044 *** | 0.013 | −1.273 |

| (0.057) | (0.132) | (0.012) | (0.016) | (2.708) | |

| Ln_Assets | −0.557 *** | −0.714 *** | −0.024 ** | −0.033 | −2.768 |

| (0.048) | (0.108) | (0.010) | (0.020) | (2.292) | |

| Efficiency | −0.003 *** | −0.004 *** | −0.000 | 0.055 *** | −0.019 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.007) | (0.025) | |

| Debt_to_Equity | −0.118 *** | 0.042 | −0.018 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.577 |

| (0.010) | (0.027) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.484) | |

| Controlled by Geographical Cluster | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 18.634 *** | 17.454 *** | 0.353 *** | 0.389 | 42.633 |

| (0.572) | (1.301) | (0.123) | (0.250) | (27.591) | |

| Observations | 835 | 738 | 835 | 834 | 822 |

| R-squared | 0.281 | 0.074 | 0.104 | 0.223 | 0.004 |

| Number of companies | 98 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 98 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Ln Sales | Ln EBITDA | EBITDA/Sales | EBITDA/Assets | ROE |

| Certifications × Disclosure (0;1) | −0.012 | 0.099 | 0.003 | 0.011 | 1.615 |

| (0.022) | (0.083) | (0.020) | (0.008) | (2.167) | |

| Certifications × Disclosure (1;1) | −0.011 | 0.046 | −0.001 | 0.010 | −1.585 |

| (0.022) | (0.086) | (0.020) | (0.008) | (2.194) | |

| Ln_Assets | 0.941 *** | 1.152 *** | 0.051 *** | 0.024 *** | 9.128 *** |

| (0.021) | (0.085) | (0.019) | (0.008) | (2.054) | |

| Efficiency | 0.902 *** | 1.223 *** | 0.099 *** | 0.138 *** | 21.781 *** |

| (0.028) | (0.113) | (0.025) | (0.010) | (2.747) | |

| Debt_to_Equity | −0.040 *** | 0.021 | −0.010 *** | 0.002 * | 0.472 |

| (0.003) | (0.014) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.321) | |

| Controlled by Geographical Cluster | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −0.232 | −5.728 *** | −0.600 ** | −0.343 *** | −116.994 *** |

| (0.262) | (1.081) | (0.237) | (0.098) | (25.804) | |

| Observations | 875 | 811 | 875 | 877 | 874 |

| R-squared | 0.753 | 0.233 | 0.037 | 0.196 | 0.078 |

| Number of companies | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruberti, M.; Calciolari, S. Environmental Certifications as Strategic Assets? Evidence from Italian Chemical and Pharmaceutical Firms. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100562

Ruberti M, Calciolari S. Environmental Certifications as Strategic Assets? Evidence from Italian Chemical and Pharmaceutical Firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(10):562. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100562

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuberti, Massimo, and Stefano Calciolari. 2025. "Environmental Certifications as Strategic Assets? Evidence from Italian Chemical and Pharmaceutical Firms" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 10: 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100562

APA StyleRuberti, M., & Calciolari, S. (2025). Environmental Certifications as Strategic Assets? Evidence from Italian Chemical and Pharmaceutical Firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(10), 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100562