Investigation of the Antecedents of Personal Saving Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review Using TCM-ADO Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the temporal trends and publication patterns of the published research on saving behavior over the years?

- Identify the authors significantly contributing to the study of individual saving behavior and what they bring to the field

- What are the emergent themes based on keyword analysis in the research landscape of saving behavior?

- What are the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes related to individual saving behavior, along with their theoretical foundations?

- What are the key contextual settings within the research field of individual saving behavior?

- What are the major research methods used to collect and analyze data in the reviewed research papers?

- We propose a hybrid strategy that includes a comprehensive literature review and bibliometric analysis, allowing us to present the knowledge bases and outline a research agenda for the future in the field of “saving behavior.”

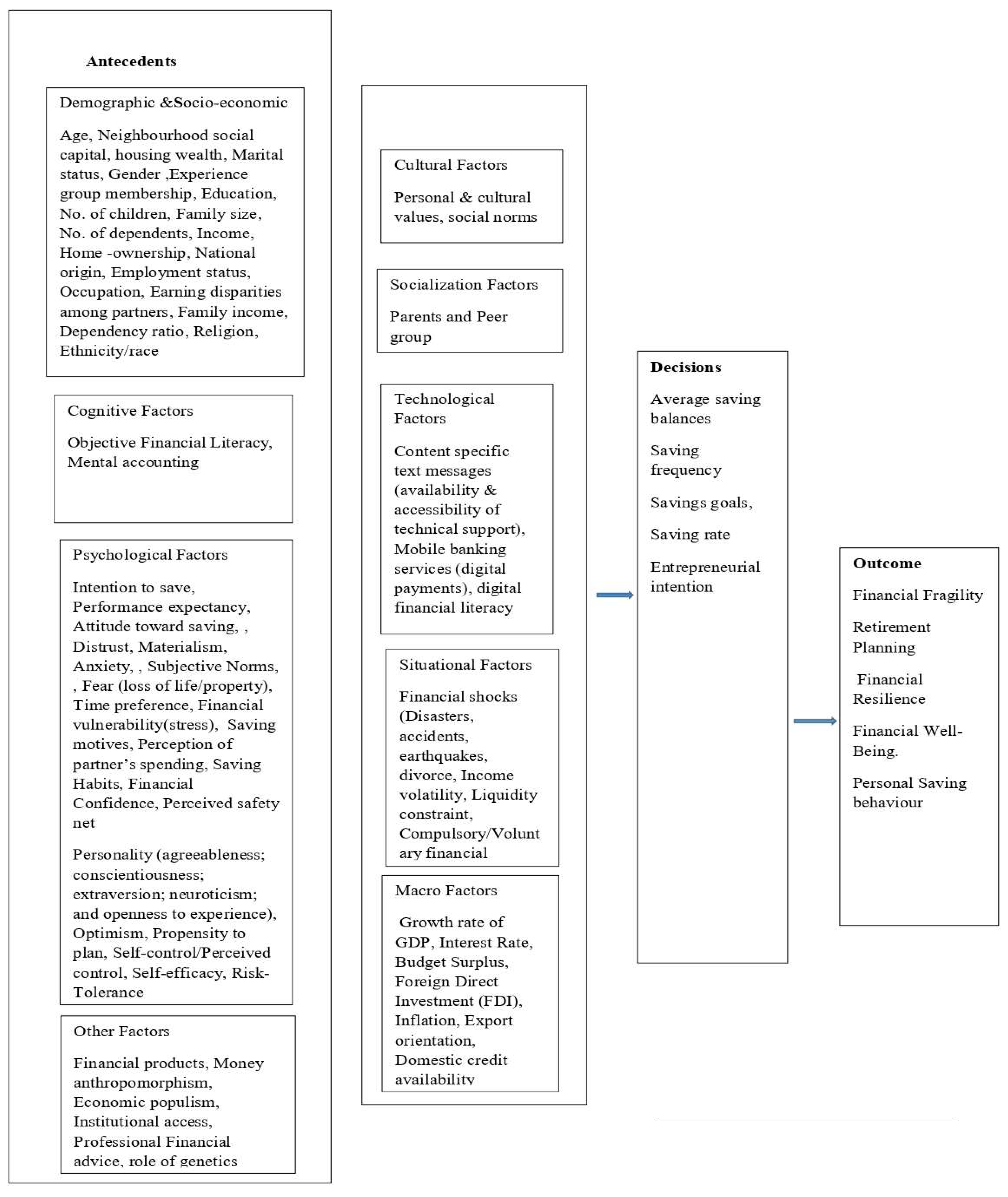

- Identifies both micro- and macro-level antecedents based on research from 2020 to 2025, unlike earlier reviews that only examined these factors in a fragmented manner.

- This study employs a systematic review method based on two frameworks: the TCM (Theory, Context, and Methods) framework by Paul et al. (2024) and the ADO (Antecedents, Decisions, and Outcomes) framework by Paul and Benito (2018). This enhances the organization and structure of the review concerning saving behavior research, in contrast to the (semi-)structured review methods used in previous studies.

- Unlike previous reviews that relied on a single-level categorization, this comprehensive analysis introduces a robust multi-level categorization of antecedents. This innovative approach provides deeper insights and greater clarity, enhancing the overall understanding of the subject matter.

- Our review highlights significant research gaps that future studies should address using the TCM and ADO frameworks.

2. Methodology

- Domain-based reviews concentrate on examining knowledge pertaining to the topic, split into five categories:

- (a)

- Structured reviews aim to synthesize theories, constructs, contexts, and prevalent methods documented in literature on specific research themes (Canabal & White, 2008).

- (b)

- Framework-based reviews rely on established models like the ADO, TCM, or the 7P framework to structure the review and extract valuable insights related to the research subject (Lim, 2025; Lim et al., 2021; Paul & Benito, 2018). Authors might develop their own frameworks for the reviewing process.

- (c)

- Bibliometric reviews emphasize statistics regarding publication years, journals, and authors (Donthu et al., 2021).

- (d)

- Hybrid reviews integrate elements from various domain-specific review types (Lim et al., 2021; Paul et al., 2024).

- (e)

- Reviews dedicated to theory development aim to formulate theoretical models, hypotheses, or propositions for future validation (Paul, 2020; Sharma & Kushwah, 2025).

- Theory-based reviews offer a comprehensive examination of how different theories influence a particular research area (Gilal et al., 2020, 2023; Lim et al., 2021).

- Meta-analytical reviews evaluate effect sizes of various variables, highlighting the strength of their relationships using statistical techniques such as the weighted average method (Rana & Paul, 2020; Tang & Buckley, 2020).

- Method-focused reviews concentrate on the current knowledge surrounding specific methods employed in the field (Jia et al., 2012).

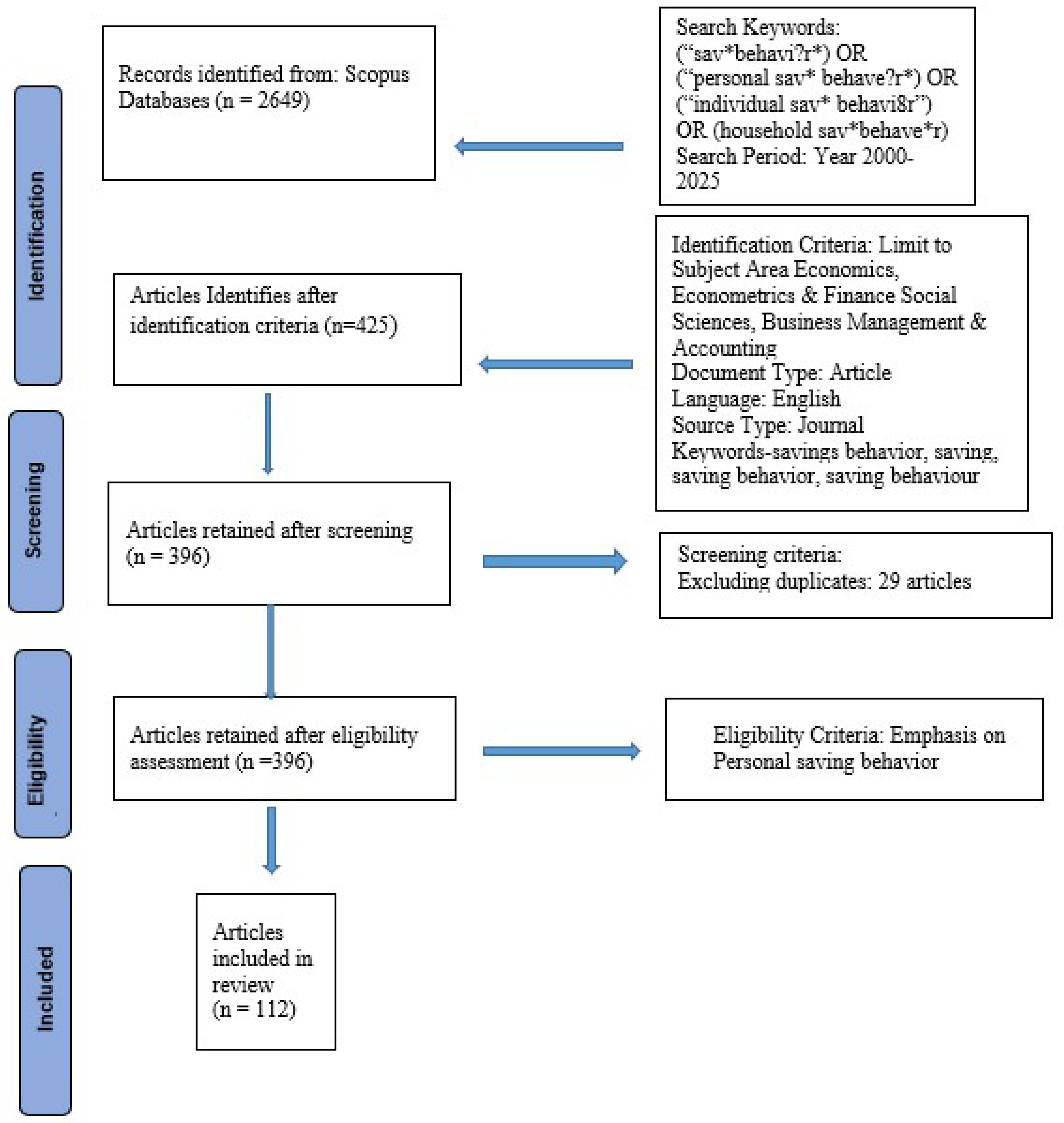

Review Approach

- The study aims to understand individual saving behavior.

- Articles on energy-saving behavior or government saving were excluded. The authors manually reviewed 396 articles. Using the inclusion criteria noted earlier, along with discussions and consensus among the authors, 112 articles were chosen for this review. During the inclusion process, a detailed content analysis was conducted, focusing on extracting, coding, and organizing data from these articles.

3. Bibliographic Analysis

3.1. Authors Who Are Highly Prolific in Saving Behavior Research

| Most Productive Authors | Most Cited Authors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Total Publications | Author | Total Citations |

| Fisher Patti J. | 3 | Horioka Charles Y. | 1471 |

| Gutter Michael S. | 3 | Lensink Robert | 132 |

| Hanna Sherman D. | 3 | Price Debora | 130 |

| Horioka Charles Y. | 3 | Börsch Supan A | 128 |

| Loibl Cäzilia | 3 | Cook Christopher J. | 124 |

| Wahbi Annkathrin | 3 | Mauldin Teresa | 123 |

| Adami Roberta | 2 | Cho Soo Hyun | 105 |

| Alessie Rob | 2 | Kim Jinhee | 93 |

| Athukorala Prema-Chandra | 2 | Gough Orla | 90 |

| Benartzi Shlomo | 2 | Hermansson C | 73 |

3.2. Highly Productive Documents on Saving Behavior Research

| Year | Author | Global Citation Score | Document Title | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Thaler Richard H | 1448 | Save more tomorrow: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving | Journal of Political Economy |

| 2004 | Berk, Jonathan B | 1048 | Mutual fund flows and performance in rational markets | Journal of Political Economy |

| 2002 | Glaeser, Edward L | 926 | An economic approach to social capital | Economic Journal |

| 2001 | Appadurai, A. | 566 | Deep democracy: Urban governmentality and the horizon of politics | Environment and Urbanization |

| 2004 | Dynan, Karen E | 490 | Do the rich save more? | Journal of Political Economy |

| 2007 | Puri, Manju | 459 | Optimism and economic choice | Journal of Financial Economics |

| 2005 | French, Eric | 396 | The effects of health, wealth, and wages on labour supply and retirement behaviour | Review of Economic Studies |

| 2009 | Ersner-Hershfield | 313 | Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow: Individual differences in future self-continuity account for saving | Judgment and Decision Making |

| 2003 | Zimmerman, Frederick J. | 299 | Asset smoothing, consumption smoothing and the reproduction of inequality under risk and subsistence constraints | Journal of Development Economics |

| 2005 | Fankhauser, Samuel | 263 | On climate change and economic growth | Resource and Energy Economic |

3.3. Key Journals in Savings Behavior Research

| Source | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Political Economy | 7 | 3468 | 4 |

| Economic Journal | 9 | 1273 | 2 |

| Journal of Development Economics | 11 | 661 | 8 |

| Review of Economic Studies | 3 | 489 | 0 |

| World Bank Economic Review | 7 | 467 | 12 |

| Judgment and decision making | 2 | 321 | 2 |

| journal of human resources | 6 | 320 | 1 |

| Oxford Economic Papers | 4 | 254 | 9 |

| Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning | 7 | 248 | 10 |

| Journal of Economic Psychology | 8 | 182 | 3 |

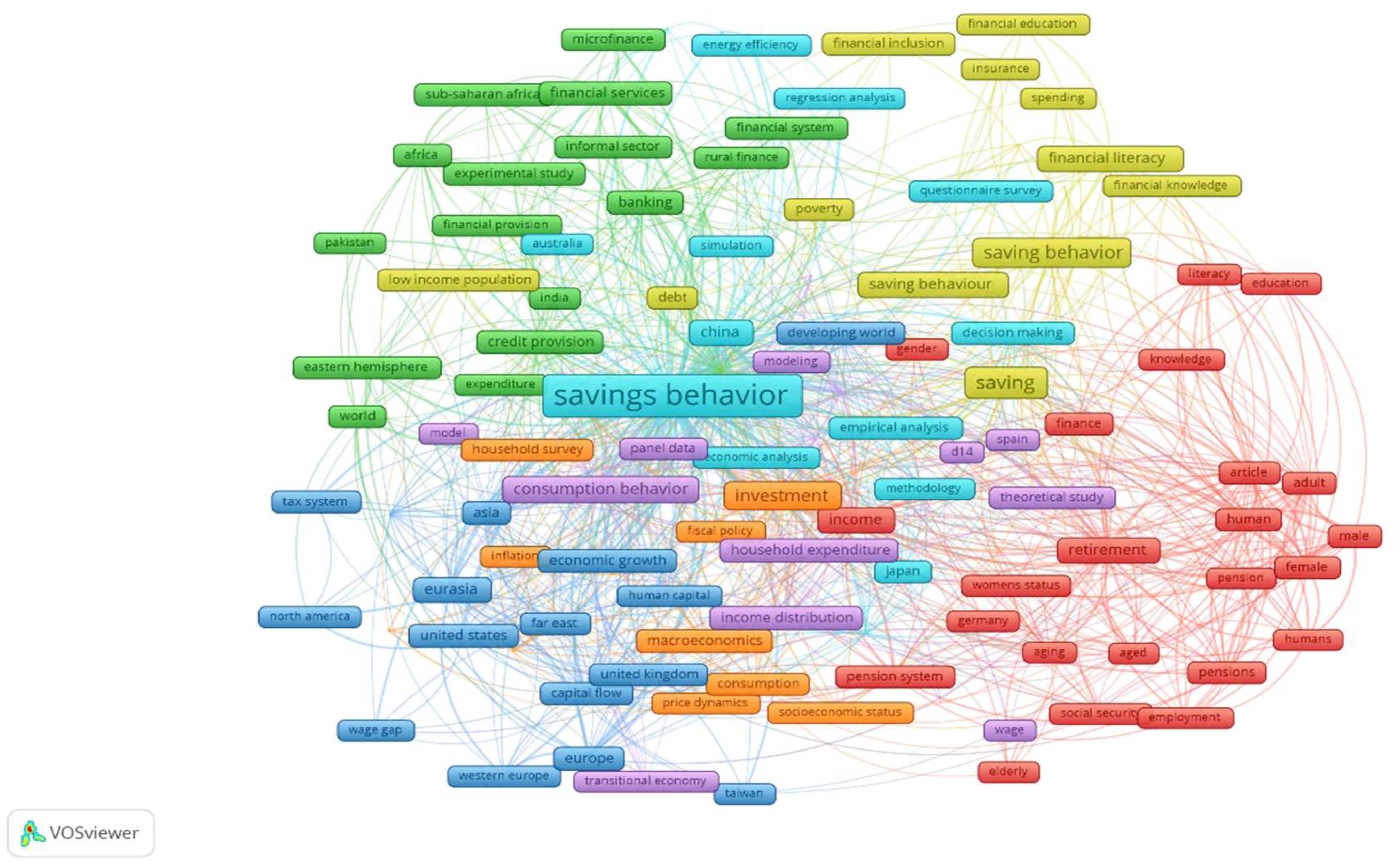

3.4. Key Author Keywords in Saving Behavior Research

| Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Savings Behavior | 276 | 937 |

| Saving | 73 | 150 |

| Saving Behavior | 61 | 105 |

| Investment | 51 | 199 |

| Savings | 48 | 237 |

| Consumption Behavior | 41 | 163 |

| Income | 30 | 149 |

| Saving Behaviour | 29 | 45 |

| Financial Literacy | 25 | 78 |

| Retirement | 25 | 157 |

| Cluster | Themes Identified | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (Red) | Saving behavior and retirement and income | Adult, aged, female, income, pension |

| Cluster 2 (Green) | Saving behavior and financial system | Banking, credit provision, financial market, financial services, informal sector |

| Cluster 3 (Dark blue) | Saving behavior and economic and geographic factors | Asia, Eurasia, comparative study, developing world, economic growth |

| Cluster 4 (Light green) | Saving behavior and cognitive factors | Financial education, financial knowledge, financial literacy, financial planning, household finance |

| Cluster 5 (Purple) | Saving behavior and consumption and investment behavior | Consumption behavior, household expenditure, household income, income distribution, precautionary savings |

| Cluster 6 (Light blue) | Saving behavior and empirical and methodological approaches | Decision-making, economic analysis, empirical analysis, methodology, regression analysis |

| Cluster 7 (Orange) | Saving behavior and macro-economic factors | Capital market, fiscal policy, inflation, macroeconomics, monetary policy |

3.5. Countries That Are Highly Productive in Researching Saving Behaviors

4. Review of Studies—TCM-Based Framework

5. Review of Studies Based on ADO Framework

6. Implications

7. Directions for Future Research

- In what ways do religious beliefs and cultural practices influence personal saving habits in different regions or societies?

- Do consumers in emerging economies have different saving habits compared to those in developed countries, and what factors shape these differences in saving behavior?

- Neuroscientific methodologies employ neuroimaging techniques to investigate brain regions and processes implicated in saving behavior, thereby elucidating the neurological foundations of risk-taking, a field frequently referred to as Neuro finance.

- Big data analytics and machine learning are applied to assess risk tolerance across various populations and to discover new factors affecting saving preferences using large datasets and sophisticated algorithms.

- Experimental designs involve manipulating multiple variables to investigate causal relationships between specific traits and saving behavior, thereby enhancing understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

- Longitudinal and cross-cultural studies provide valuable insights into the evolution and variation of saving behaviors across different societies. These behaviors are significantly influenced by cultural norms and shifts within the social landscape.

- Dynamic modeling builds representations of how individuals’ saving results respond to economic, social, and psychological influences.

- Integrative approaches utilize both quantitative and qualitative methodologies to provide a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between personal traits and environmental factors in influencing saving behavior.

- In developing countries such as India and other Asian economies, deep-rooted cultural norms particularly those related to patriarchy, masculinity and high power distance may significantly moderate the relationship between various antecedents and individuals saving behaviors and financial outcomes.

- Future research should examine how regulatory orientation affects complex financial tasks like investment decisions, with consumers having a prevention focus potentially achieving better outcomes. Socialization agents, such as parents and media, significantly shape early investment habits, and their influence varies by regulatory orientation. Additionally, addressing cognitive biases and limitations in financial literacy education is vital, and customizing educational programs to align with individuals’ regulatory orientations could enhance their effectiveness.

- The connection between saving intentions and actual behavior has not been widely studied thus it would be interesting to explore how and when intentions merge into behavior.

- Since this is an emerging field, a thorough study could explore the role of financial consultants and analyze how factors like emotions and mood influence savings habits. Moreover, research could investigate why some individuals opt out of savings and investment activities.

- Future studies should gather spender-saver data from both partners, including income and resources, to better understand gender differences linked to income and wealth. Collecting more data on partner finances and attitudes can assist financial therapists working with couples. Researching how partner collaboration on finances affects satisfaction and perceptions of saving and spending, as well as how these perceptions influence relationship outcomes, is also valuable.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agrawal, P., Pravakar, S., & Dash, R. K. (2010). Savings behavior in India: Co-integration and causality evidence. The Singapore Economic Review, 55(02), 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., Lensink, R., & Mueller, A. (2023). Uptake, use, and impact of Islamic savings: Evidence from a field experiment in Pakistan. Journal of Development Economics, 163, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, K. F. (2016). Consumer perceptions and saving behaviour [Working Paper]. Department of Economics and Centre for Finance, Law and Policy, Boston University. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2000). Attitudes and the attitude-behavior relation: Reasoned and automatic processes. European Review of Social Psychology, 11(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, A., Güner, D., Gürsel, S., & Uysal, G. (2012). Structural determinants of household savings in Turkey: 2003–2008 [Doctoral dissertation, Bahçesehir University Centre for Economic and Social Research (BETAM)]. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Awad, M., & Elhiraika, A. (2003). Cultural effects and savings: Evidence from immigrants to the United Arab Emirates. The Journal of Development Studies, 39(5), 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfi, C. F., & Yusuf, S. N. S. (2022). Religiosity and saving behavior: A preliminary investigation among muslim students in Indonesia. Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance, 8(1), 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgood, S., & Walstad, W. B. (2016). The effects of perceived and actual financial literacy on financial behaviors. Economic Inquiry, 54(1), 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allom, V., Mullan, B. A., Monds, L., Orbell, S., Hamilton, K., Rebar, A. L., & Hagger, M. S. (2018). Reflective and impulsive processes underlying saving behavior and the additional roles of self-control and habit. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 11(3), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alós-Ferrer, C., & Strack, F. (2014). From dual processes to multiple selves: Implications for economic behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A. S., & Seraj, A. H. A. (2021). The antecedents of saving behavior and entrepreneurial intention of Saudi Arabia University students. Kuram ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri, 21(2), 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, M., Salhi, B., & Jarboui, A. (2020). Evaluating the effects of sociodemographic characteristics and financial education on saving behavior. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 40(11/12), 1423–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammer, M. A., & Aldhyani, T. H. (2022). An investigation into the determinants of investment awareness: Evidence from the young Saudi generation. Sustainability, 14(20), 13454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, A., Tetteh, C. K., Osei-Bonsu, N., Pomeyie, P., Ahiabor, G., Hughes, G., & Otchere-Ankrah, B. (2024). Determinants of household saving behaviour in Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1), 2420220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, S., Kumar, R. P., & Dalwai, T. (2024). Impact of financial literacy on savings behavior: The moderation role of risk aversion and financial confidence. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29(3), 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, A., & Modigliani, F. (1963). The “life cycle” hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. The American Economic Review, 53(1), 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, J. (2009). Household saving behaviour in an extended life cycle model: A comparative study of China and India. Journal of Development Studies, 45(8), 1344–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Anvari-Clark, J., & Ansong, D. (2022). Predicting financial well-being using the financial capability perspective: The roles of financial shocks, income volatility, financial products, and savings behaviors. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 43(4), 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asebedo, S. D., & Seay, M. C. (2018). Financial self-efficacy and the saving behavior of older pre-retirees. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 29(2), 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Asebedo, S. D., & Wilmarth, M. J. (2017). Does how we feel about financial strain matter for mental health? Journal of Financial Therapy, 8(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athukorala, P. C., & Suanin, W. (2024). Saving Transition in Asia. The Journal of Development Studies, 60(8), 1211–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athukorala, P. C., & Tsai, P. L. (2003). Determinants of household saving in Taiwan: Growth, demography and public policy. The Journal of Development Studies, 39(5), 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, R. B., & Kennickell, A. B. (1991). Household Saving in the US. Review of Income and Wealth, 37(4), 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassa, B. (1989). Outward orientation. In Handbook of development economics (vol. 2, pp. 1645–1689). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., O’Leary, A., Taylor, C. B., Gauthier, J., & Gossard, D. (1987). Perceived self-efficacy and pain control: Opioid and nonopioid mechanisms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capita. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, E., & Mare, D. S. (2017). Formal and informal household savings: How does trust in financial institutions influence the choice of saving instruments? [MPRA Paper 81141]. University Library of Munich, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, P., & Jacob, J. (2024). Neighbourhood social capital, account usage and savings behaviour in low-income countries: Field experimental evidence from Senegal. Journal of International Development, 36(1), 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, J. B., & Green, R. C. (2004). Mutual fund flows and performance in rational markets. Journal of Political Economy, 112(6), 1269–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernoulli, D. (2011). Exposition of a new theory on the measurement of risk. In The Kelly capital growth investment criterion: Theory and practice (pp. 11–24). World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Beverly, S. G., McBride, A. M., & Schreiner, M. (2003). A framework of asset-accumulation stages and strategies. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 24(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverly, S. G., & Sherraden, M. (1999). Institutional determinants of saving: Implications for low-income households and public policy. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 28(4), 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghans, L., Duckworth, A. L., Heckman, J. J., & Ter Weel, B. (2008). The economics and psychology of personality traits. Journal of Human Resources, 43(4), 972–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boto-García, D., Bucciol, A., & Manfrè, M. (2022). The role of financial socialization and self-control on saving habits. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 100, 101903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A., & Mendes, V. (2021). Savings and financial literacy: A selected review. Savings and Financial Literacy: A Selected Review, (1), 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S., & Taylor, K. (2006). Financial expectations, consumption and saving: A microeconomic analysis. Fiscal Studies, 27(3), 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S., & Taylor, K. (2016). Early influences on saving behaviour: Analysis of British panel data. Journal of Banking & Finance, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, M. (2000). The saving behaviour of a two-person household. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 102(2), 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M., & Crossley, T. F. (2001). The life-cycle model of consumption and saving. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(3), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M., & Lusardi, A. (1996). Household saving: Micro theories and micro facts. Journal of Economic Literature, 34(4), 1797–1855. [Google Scholar]

- Burney, N. A., & Khan, A. H. (1992). Socio-economic characteristics and household savings: An analysis of the households’ saving behaviour in Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review, 31(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, D. (2001). Savings and investment behaviour in Britain: More questions than answers. Service Industries Journal, 21(3), 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, M., Fiala, N., Mulaj, F., Sadhu, S., & Sarr, L. (2018). Financial education and savings behavior: Evidence from a randomized experiment among low-income clients of branchless banking in India. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 66(4), 793–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. R., & Hercowitz, Z. (2019). Liquidity constraints of the middle class. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11(3), 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canabal, A., & White, G. O., III. (2008). Entry mode research: Past and future. International Business Review, 17(3), 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canare, T., Francisco, J. P. S., & Jopson, E. M. M. M. (2019). Fear of crime and saving behavior. Review of Economic Analysis, 11(3), 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. B., & Jensen, R. T. (2002). Household participation in formal and informal savings mechanisms: Evidence from Pakistan. Review of Development Economics, 6(3), 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakma, R., Paul, J., & Dhir, S. (2021). Organizational ambidexterity: A review and research agenda. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhillar, N., & Arora, S. (2023). Financial Literacy and its Determinants: A Systematic review. Acta Universitatis Bohemiae Meridionales, 26(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W. T., & Ho, Y. S. (2007). Bibliometric analysis of tsunami research. Scientometrics, 73(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. H., Loibl, C., & Geistfeld, L. (2014). Motivation for emergency and retirement saving: An examination of R egulatory F ocus T heory. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(6), 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y., & Han, J. S. (2018). Time preference and savings behaviour. Applied Economics Letters, 25(14), 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K. L., Yu, K. M., Chan, W. S., Chan, A. C., Lum, T. Y., & Zhu, A. Y. (2014). Social and psychological barriers to private retirement savings in Hong Kong. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 26(4), 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudzian, J., Aniola-Mikolajczak, P., & Pataraia, L. (2015). Motives and attitudes for saving among young Georgians. Economics & Sociology, 8(1), 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). (2017, September 26). Financial well-being in America. Consumer financial protection bureau. Available online: https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/financial-well-being-america/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Copur, Z., & Gutter, M. S. (2019). Economic, sociological, and psychological factors of the saving behavior: Turkey case. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(2), 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronqvist, H., & Siegel, S. (2015). The origins of savings behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 123(1), 123–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronqvist, H., & Thaler, R. H. (2004). Design choices in privatized social-security systems: Learning from the Swedish experience. American Economic Review, 94(2), 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L. A., Peñaloza, V., Porto, N., & An, T. (2025). The role of personal and cultural values on saving behavior: A cross-national analysis. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 45(1/2), 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. (1977). Involuntary saving through unanticipated inflation. The American Economic Review, 67(5), 899–910. [Google Scholar]

- DeVaney, S. A., Anong, S. T., & Whirl, S. E. (2007). Household savings motives. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 41(1), 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, M. D. (2020). The correlation between financial literacy and personal saving behavior in Vietnam. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 10(6), 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, J. M., & Cross, C. (2013). Fraud and its PREY: Conceptualising social engineering tactics and its impact on financial literacy outcomes. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 18(3), 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duesenberry, J. S. (1948). Income—Consumption relations and their implications. In L. Metzler (Ed.), Income, employment and public policy. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Durante, K. M., & Laran, J. (2016). The effect of stress on consumer saving and spending. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(5), 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, M., Kier, C., Leung, A., & Sproule, R. (2006). Peer crowds, work experience, and financial saving behaviour of young Canadians. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27(2), 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J., Hao, W., & Reyers, M. (2022). Financial advice, financial literacy and social interaction: What matters to retirement saving decisions? Applied Economics, 54(50), 5827–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, L., Fry, T. R., & Risse, L. (2016). The significance of financial self-efficacy in explaining women’s personal finance behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology, 54, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipski, M., Jin, L., Zhang, X., & Chen, K. Z. (2019). Living like there’s no tomorrow: The psychological effects of an earthquake on savings and spending behavior. European Economic Review, 116, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. (1957). The permanent income hypothesis. In A theory of the consumption function (pp. 20–37). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs-Schündeln, N., Masella, P., & Paule-Paludkiewicz, H. (2020). Cultural determinants of household saving behavior. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 52(5), 1035–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. T. M., Barros, C., & Silvestre, A. (2011). Saving behaviour: Evidence from Portugal. International Review of Applied Economics, 25(2), 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, A., & Rossi, A. G. (2024). Goal setting and saving in the fintech era. The Journal of Finance, 79(3), 1931–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, S. T., & Gutter, M. (2010). 2010 outstanding AFCPE® conference paper: Gender differences in financial socialization and willingness to take financial risks. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 21(2), 60–72, 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard, P., Gladstone, J. J., & Hoffmann, A. O. (2018). Psychological characteristics and household savings behavior: The importance of accounting for latent heterogeneity. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 148, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, C., & Chaudhury, R. H. (2023). A comparative study of saving behaviour between India and China. Millennial Asia, 14(4), 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F. G., Chandani, K., Gilal, R. G., Gilal, N. G., Gilal, W. G., & Channa, N. A. (2020). Towards a new model for green consumer behaviour: A self-determination theory perspective. Sustainable Development, 28(4), 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F. G., Paul, J., Gilal, R. G., & Gilal, N. G. (2023). Advancing basic psychological needs theory in marketing research. International Journal of Market Research, 65(6), 745–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilenko, E., & Chernova, A. (2021). Saving behavior and financial literacy of Russian high school students: An application of a copula-based bivariate probit-regression approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 127, 106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giné, X., Goldberg, J., Silverman, D., & Yang, D. (2018). Revising commitments: Field evidence on the adjustment of prior choices. The Economic Journal, 128(608), 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, O. (2025). The distribution of savings behaviours and macro dynamics. Oxford Economic Papers, 77(2), 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L., & Özcan, B. (2013). The risk of divorce and household saving behavior. Journal of Human Resources, 48(2), 404–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gouveia, V. V. (1998). The nature of individualist and collectivist values: A within and between cultures comparison [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Complutense University of Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., & Guerra, V. M. (2014). Functional theory of human values: Testing its content and structure hypotheses. Personality and Individual Differences, 60, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K., & Kumar, S. (2021). Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(1), 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grable, J., Kruger, M., Byram, J. L., & Kwak, E. J. (2021). Perceptions of a partner’s spending and saving behavior and financial satisfaction. Journal of Financial Therapy, 12(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröbel, S., & Ihle, D. (2018). Saving behavior and housing wealth evidence from german micro data. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, 238(6), 501–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmunson, C. G., & Danes, S. M. (2011). Family financial socialization: Theory and critical review. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 644–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, R., & Balachandar, A. (2024). Digital payment technology and consumer behaviour—Saving, spending patterns: Are saving and spending patterns a concern? Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases, 14(2), 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutter, M. S., Garrison, S., & Copur, Z. (2010). Social learning opportunities and the financial behaviors of college students. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 38(4), 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutter, M. S., Hayhoe, C. R., DeVaney, S. A., Kim, J., Bowen, C. F., Cheang, M., Cho, S. H., Evans, D. A., Gorham, E., Lown, J. M., Mauldin, T., Solheim, C., Worthy, S. L., & Dorman, R. (2012). Exploring the relationship of economic, sociological, and psychological factors to the savings behavior of low-to moderate-income households. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 41(1), 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, S., Thoyib, A., Sumiati, S., & Djazuli, A. (2022). The impact of financial literacy on retirement planning with serial mediation of financial risk tolerance and saving behavior: Evidence of medium entrepreneurs in Indonesia. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10(3), 66. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. N., Loundes, J., & Webster, E. (2002). Determinants of household saving in Australia. Economic Record, 78(241), 207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J. J. (2010). Building bridges between structural and program evaluation approaches to evaluating policy. Journal of Economic literature, 48(2), 356–398. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, S., & Hanna, S. D. (2015). Individual and institutional factors related to low-income household saving behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 26(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemrajani, P., Khan, M., & Dhiman, R. (2023). Financial risk tolerance: A review and research agenda. European Management Journal, 41(6), 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henager, R., & Mauldin, T. (2015). Financial literacy: The relationship to saving behavior in low-to moderate-income households. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 44(1), 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansson, C., & Song, H. S. (2016). Financial advisory services meetings and their impact on saving behavior–A difference-in-difference analysis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 30, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Perez, J., & Cruz Rambaud, S. (2025). Uncovering the factors of financial well-being: The role of self-control, self-efficacy, and financial hardship. Future Business Journal, 11(1), 70. [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, D. A., Henkens, K., & Van Dalen, H. P. (2010). Aging and financial planning for retirement: Interdisciplinary influences viewed through a cross-cultural lens. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 70(1), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, D. A., & Mowen, J. C. (2000). Psychological determinants of financial preparedness for retirement. The Gerontologist, 40(6), 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hii, I. S., Ho, J. M., Zhong, Y., & Li, X. (2025). Savings in the digital age: Can Internet wealth management services enhance savings behaviour among Chinese Gen Z? Managerial Finance, 51(4), 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, M. A., Hogarth, J. M., & Beverly, S. G. (2003). Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 89, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Hira, T. K. (2012). Promoting sustainable financial behaviour: Implications for education and research. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 36(5), 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(46), 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W., Friese, M., & Wiers, R. W. (2008). Impulsive versus reflective influences on health behavior: A theoretical framework and empirical review. Health Psychology Review, 2(2), 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s recent consequences: Using dimension scores in theory and research. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 1(1), 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopf, G. (2006). A critical assessment of past investigations into Singapore’s saving behavior. The Singapore Economic Review, 51(1), 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horioka, C. Y. (2019). Are the Japanese unique? Evidence from saving and bequest behavior. The Singapore Economic Review, 64(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, T. X., & Erreygers, G. (2020). Applying quantile regression to determine the effects of household characteristics on household saving rates in Vietnam. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies, 27(2), 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, S. J. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingale, K. K., & Paluri, R. A. (2022). Financial literacy and financial behaviour: A bibliometric analysis. Review of Behavioral Finance, 14(1), 130–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingale, K. K., & Paluri, R. A. (2025). Retirement planning—A systematic review of literature and future research directions. Management Review Quarterly, 75(1), 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L., You, S., & Du, Y. (2012). Chinese context and theoretical contributions to management and organization research: A three-decade review. Management and Organization Review, 8(1), 173–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D., & Widdows, R. (1985, March). Emergency fund levels of households. In The proceedings of the American Council on consumer interests 31th annual conference (Vol. 235, p. 241). American Council on Consumer Interests. [Google Scholar]

- Jongwanich, J. (2010). The determinants of household and private savings in Thailand. Applied Economics, 42(8), 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumena, B. B., Siaila, S., & Widokarti, J. R. (2022). Saving behaviour: Factors that affect saving decisions (Systematic literature review approach). Jurnal Economic Resource, 5(2), 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2003). Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics. American Economic Review, 93(5), 1449–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). 22Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Preference, Belief, and Similarity, 549, 263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2017). Does financial education impact financial literacy and financial behavior, and if so, when? The World Bank Economic Review, 31(3), 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2020). Financial education in schools: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Economics of Education Review, 78, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, P. A., Mehta, A., & Rani, N. (2025). Measuring Multidimensional Financial Resilience: An Ex-Ante Approach. Social Indicators Research, 176(2), 533–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlan, D., Ratan, A. L., & Zinman, J. (2014). Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review and Agenda. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(1), 36–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempson, E., Finney, A., & Poppe, C. (2017). Financial well-being. A conceptual model and preliminary analysis. SIFO Project Note. 3–2017. Consumption Research Norway (SIFO). [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, J. M. (1936). William Stanley Jevons. In Essays in biography (pp. 109–160). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja, M. J. (2023). Determinants of savings behaviour in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Social Economics, 50(5), 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiiza, B., & Pederson, G. (2001). Household financial savings mobilisation: Empirical evidence from Uganda. Journal of African Economies, 10(4), 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O. V. T., Thuy, T. T. N., Do Khanh, L., Thanh, M. P. T., Thi, Q. N., & Minh, T. N. T. (2025). The impact of financial literacy on saving behavior of the elderly people: The mediating role of digital financial literacy. Humanities and Social Sciences Letters, 13(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinugasa, T., Masumoto, K., Yasuda, K., Yugami, K., & Hamori, S. (2024). Changes in subjective mortality expectations and savings during COVID-19: Empirical analysis using questionnaire data in Japan. Applied Economics, 56(44), 5225–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusairi, S., Sanusi, N. A., Muhamad, S., Shukri, M., & Zamri, N. (2019). Financial households’ efficacy, risk preference, and saving behaviour: Lessons from lower-income households in Malaysia. Economics & Sociology, 12(2), 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance, M. J. (2012). Young adults’ attitudes towards credit. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 36(5), 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, M., & Mthombeni, M. (2021). Determining the potential of informal savings groups as a model for formal commitment saving devices. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 24(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W. M. (2025). Systematic literature reviews: Reflections, recommendations, and robustness check. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 24(3), 1498–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Ali, F. (2022). Advancing knowledge through literature reviews:‘what’,‘why’, and ‘how to contribute’. The Service Industries Journal, 42(7–8), 481–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., Yap, S. F., & Makkar, M. (2021). Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: What do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading? Journal of Business Research, 122, 534–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos-Herrera, G. R., & Merigo, J. M. (2019). Overview of brand personality research with bibliometric indicators. Kybernetes, 48(3), 546–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaba, S. (2022). The impact of mobile banking services on saving behavior in West Africa. Global Finance Journal, 53, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, C., Kraybill, D. S., & DeMay, S. W. (2011). Accounting for the role of habit in regular saving. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(4), 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, I., Mahdzan, N. S., & Rahman, M. (2024). Saving behaviour determinants of Malaysia’s generation Y: An application of the integrated behavioural model. International Journal of Social Economics, 51(7), 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lown, J. M., Kim, J., Gutter, M. S., & Hunt, A. T. (2015). Self-efficacy and savings among middle and low income households. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36(4), 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lössbroek, J., & Van Tubergen, F. (2024). Saving behavior among immigrant and native youth. Comparative Migration Studies, 12(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, P. K., & Livingstone, S. M. (1991). Psychological, social and economic determinants of saving: Comparing recurrent and total savings. Journal of economic Psychology, 12(4), 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A. (2000). Explaining why so many households do not save. Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies, University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A. (2008). Household saving behavior: The role of financial literacy, information, and financial education programs (No. w13824). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011). Financial literacy around the world: An overview. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10(4), 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A., Schneider, D. J., & Tufano, P. (2011). Financially fragile households: Evidence and implications (No. w17072). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, A. C., & Kass-Hanna, J. (2021). A methodological overview to defining and measuring “digital” financial literacy. Financial Planning Review, 4(2), e1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenge, T. M., Makgosa, R., & Mburu, P. T. (2019). The role of demographic and attitudinal influences on the financial saving behaviour of employed adults in Botswana. International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets, 11(3), 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigó, J. M., Gil-Lafuente, A. M., & Yager, R. R. (2015). An overview of fuzzy research with bibliometric indicators. Applied Soft Computing, 27, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midamba, D. C., Jjengo, A., & Ouko, K. O. (2024a). Assessing the determinants of saving behaviour: Evidence from rural farming households in Central Uganda. Discover Sustainability, 5(1), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midamba, D. C., Jjengo, A., & Ouko, K. O. (2024b). Determinants of household saving behaviour in Ghana. Discover Sustainability, 5(1), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F. (1986). Life cycle, individual thrift, and the wealth of nations. Science, 234(4777), 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, G., & Dash, A. (2022). Do financial consultants exert a moderating effect on savings behavior? A study on the Indian rural population. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2131230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, J., & Schneider, R. (2017). The financial diaries: How American families cope in a world of uncertainty. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muhamad, S., Kusairi, S., & Zamri, N. (2021). Savings behaviour of bottom income group: Is there any role for financial efficacy and risk preference? Economics and Sociology, 14(2), 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradoglu, G., & Taskin, F. (1996). Differences in household savings behavior: Evidence from industrial and developing countries. The Developing Economies, 34(2), 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R. G., Warmath, D., Fernandes, D., & Lynch, J. G. (2018). How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(1), 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, B. M., & Newman, P. R. (2022). Theories of human development. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, J. (1996). Give: A cognitive linguistic study (No. 7). Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Nga, K. H., & Yeoh, K. K. (2015). Affective, social and cognitive antecedents of attitude towards money among undergraduate students: A Malaysian study. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 23(1), 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. A. N., Rózsa, Z., Belás, J., & Belásová, Ľ. (2017). The effects of perceived and actual financial knowledge on regular personal savings: Case of Vietnam. Journal of International Studies, 10(2), 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Letamendia, L., Sánchez-Ruiz, P., & Silva, A. C. (2025). More than knowledge: Consumer financial capability and saving behavior. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 49(1), e13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, A. (2013). Saving in childhood and adolescence: Insights from developmental psychology. Economics of Education Review, 33, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C., Joseph, M., Zhang, Y., & Naveed, K. (2025). The Interplay of Financial Safety Nets, Long-Term Goals, and Saving Habits: A Moderated Mediation Study. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, K. M., Gunay, A., & Ertac, S. (2003). Determinants of private savings behaviour in Turkey. Applied Economics, 35(12), 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. (2018). Micro study of low-income households in India: A poverty expectation hypothesis? Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 10(1), 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J. (2020). Marketing in emerging markets: A review, theoretical synthesis and extension. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 15(3), 446–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., & Benito, G. R. (2018). A review of research on outward foreign direct investment from emerging countries, including China: What do we know, how do we know and where should we be heading? Asia Pacific Business Review, 24(1), 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., & Criado, A. R. (2020). The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? International Business Review, 29(4), 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., Khatri, P., & Kaur Duggal, H. (2024). Frameworks for developing impactful systematic literature reviews and theory building: What, Why and How? Journal of Decision Systems, 33(4), 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., Lim, W. M., O’Cass, A., Hao, A. W., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), O1–O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlo, I., & Dariia, M. (2023). Left-wing Economic Populism and Savings: How Do Attitudes Influence Forward-Looking Financial Behavior? Eastern European Economics, 61(3), 238–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, V. G., & Morris, M. D. (2005). Who is in control? The role of self-perception, knowledge, and income in explaining consumer financial behavior. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(2), 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, D., & Kast, F. (2024). Savings accounts to borrow less: Experimental evidence from Chile. Journal of Human Resources, 59(1), 70–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poterba, J. M., Venti, S. F., & Wise, D. A. (2007). Rise of 401 (k) plans, lifetime earnings, and wealth at retirement. In Research findings in the economics of aging (pp. 271–304). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, M., & Robinson, D. T. (2007). Optimism and economic choice. Journal of Financial Economics, 86(1), 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, A., & Webley, P. (2007). Filling the gap between planning and doing: Psychological factors involved in the successful implementation of saving intention. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28(4), 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radipotsane, M. O. (2006). Determinants of household saving and borrowing in Botswana. IFC Bullefin, 25, 284–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rahayu, S. M., Worokinasih, S., Damayanti, C. R., Normawati, R. A., Rachmatika, A. G., & Aprilian, Y. A. (2024). The road to f inancial resilient: Testing digital financial literacy and saving behavior. Finance: Theory and Practice, 28(3), 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R. (1969). An econometric exploration of Indian saving behavior. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 64(325), 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, Z., Anak Nyirop, H. B., Md Sum, S., & Awang, A. H. (2022). The impact of financial shock, behavior, and knowledge on the financial fragility of single youth. Sustainability, 14(8), 4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J., & Paul, J. (2020). Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44(2), 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S., & Goyal, N. (2024). Financial Literacy and Financial Planning: Identifying the Extent of Association and Crucial Research Aspects Using Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. SN Computer Science, 5(6), 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranyard, R. (Ed.). (2017). Economic psychology. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Raue, M., D’Ambrosio, L. A., & Coughlin, J. F. (2020). The power of peers: Prompting savings behavior through social comparison. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 21(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remund, D. L. (2010). Financial literacy explicated: The case for a clearer definition in an increasingly complex economy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, E. (2022). Demographic changes and savings behavior: The experience of a developing country. Journal of Economic Studies, 49(4), 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolison, J. J., Hanoch, Y., & Wood, S. (2017). Saving for the future: Dynamic effects of time horizon. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 70, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, M. F., & Juen, T. T. (2014). The influence of financial literacy, saving behaviour, and financial management on retirement confidence among women working in the Malaysian public sector. Asian Social Science, 10(14), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahm, C. (2019). Direct stimulus payments to individuals. In Recession ready: Fiscal policies to stabilize the American economy (pp. 67–92). The Hamilton Project and Washington Center for Equitable Growth. [Google Scholar]

- Sakyi, D., Onyinah, P. O., Baidoo, S. T., & Ayesu, E. K. (2021). Empirical determinants of saving habits among commercial drivers in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 22(1), 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satsios, N., & Hadjidakis, S. (2018). Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) in saving behaviour of Pomak households. International Journal of Financial Research, 9(2), 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sayinzoga, A., Bulte, E. H., & Lensink, R. (2016). Financial literacy and financial behaviour: Experimental evidence from rural Rwanda. The Economic Journal, 126(594), 1571–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, M., Effendi, N., Santoso, T., Dewi, V. I., & Sapulette, M. S. (2022). Digital financial literacy, current behavior of saving and spending and its future foresight. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 31(4), 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C., & Kushwah, S. (2025). Mapping the theory of consumption values: A systematic review using the TCCM approach. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 24(2), 562–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1988). The behavioral life-cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry, 26(4), 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherraden, M. (1991). Assets and Welfare. Society, 29(1), 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherraden, M., & Barr, M. S. (2005). Institutions and inclusion in saving policy. In Building assets, building credit: Creating wealth in low-income communities (pp. 286–315). Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden, M., Schreiner, M., & Beverly, S. (2003). Income, institutions, and saving performance in individual development accounts. Economic Development Quarterly, 17(1), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoham, A., & Malul, M. (2012). The role of cultural attributes in savings rates. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 19(3), 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., & Dhir, S. (2019). Structured review using TCCM and bibliometric analysis of international cause-related marketing, social marketing, and innovation of the firm. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 16(2), 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations (1st ed., Vol. 1). W. Strahan. ISBN 978-1537480787. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, D. J., Montgomery, E. B., & Flavin, M. (1993). Toward a theory of saving. In The economics of saving (pp. 47–107). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockman, A. C. (1981). Effects of inflation on the pattern of international trade (No. w0713). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2006). Reflective and impulsive determinants of consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(3), 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swasdpeera, P., & Pandey, I. M. (2012). Determinants of personal saving: A study of salaried individuals in Thailand. Afro-Asian Journal of Finance and Accounting, 3(1), 34–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R. W., & Buckley, P. J. (2020). Host country risk and foreign ownership strategy: Meta-analysis and theory on the moderating role of home country institutions. International Business Review, 29(4), 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel Nalın, H. (2013). Determinants of household saving and portfolio choice behaviour in Turkey. Acta Oeconomica, 63(3), 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4(3), 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H., & Benartzi, S. (2004). Save more tomorrow™: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving. Journal of Political Economy, 112(S1), S164–S187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, S., Kumar, S., & Sureka, R. (2021). Financial Planning for Retirement: Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Directions. Journal of Financial Counseling & Planning, 32(2), 344–362. [Google Scholar]

- Tonsing, K. N., & Ghoh, C. (2019). Savings attitude and behavior in children participating in a matched savings program in Singapore. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topa, G., & Herrador-Alcaide, T. (2016). Procrastination and financial planning for retirement: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 9(3–4), 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint-Comeau, M. (2021). Liquidity constraints and debts: Implications for the saving behavior of the middle class. Contemporary Economic Policy, 39(3), 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzcińska, A., Sekścińska, K., & Maison, D. (2022). To spend or to save? The role of time perspective in the saving behavior of children. Young Consumers, 23(4), 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uy, C., Manalo, R. A., & Bayona, S. P. (2024). Determinants of saving behavior of working professionals: An intergenerational perspective. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 13(2), 372–390. [Google Scholar]

- Vadde, S. (2015). Impact of socio-demographic and economic factors on households’ savings behaviour: Empirical evidence from Ethiopia. Indian Journal of Finance, 9(3), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, P. T. T., Ngo, T. N. A., Son, V. T., & Le, T. T. (2024). An empirical investigation on determinants of saving intention towards saving behavior of young people in the post-COVID-19 era. Risk Governance & Control: Financial Markets & Institutions, 14(2), 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay Kumar, V. M., & Senthil Kumar, J. P. (2023). Insights on financial literacy: A bibliometric analysis. Managerial Finance, 49(7), 1169–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walstad, W. B., & Wagner, J. (2023). Required or voluntary financial education and saving behaviors. The Journal of Economic Education, 54(1), 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Kim, S., & Zhou, X. (2023). Money in a “safe” place: Money anthropomorphism increases saving behavior. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 40(1), 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wärneryd, K. E. (1999). The psychology of saving. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J. V. (1996). What is social comparison and how should we study it? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(5), 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worasatepongsa, P., & Deesukanan, C. (2022). The structural equation modelling of factors affecting savings and investment behaviors of generations Z in Thailand. International Journal of eBusiness and eGovernment Studies, 14(1), 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T., Wang, Z., & Li, K. (2014). Financial literacy overconfidence and stock market participation. Social Indicators Research, 119(3), 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J. (2008). Applying behavior theories to financial behavior. In Handbook of consumer finance research (pp. 69–81). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J. J., & Anderson, J. G. (1997). Hierarchical financial needs reflected by household financial asset shares. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 18(4), 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J., & Wu, J. (2008). Completing debt management plans in credit counseling: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Financial Counseling and Planning, 19(2), 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M., & Banerji, P. (2025). Digital financial literacy, saving and investment behaviour in India. Journal of Social and Economic Development, 27(2), 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D., Xu, Y., & Zhang, P. (2019). How a disaster affects household saving: Evidence from China’s 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Journal of Asian Economics, 64, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R., & Cheng, G. (2017). Millennials’ retirement saving behavior: Account ownership and balance. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 46(2), 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D. W., & Hanna, S. D. (2024). The relationship between self-control factors and household saving behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 35(3), 10–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuh, Y., & Hanna, S. D. (2010). Which households think they save? Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(1), 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal Alam, M. A., Chen, Y. C., & Mansor, N. (2023). Mental accounting and savings behavior: Evidence from machine learning method. Journal of Financial Counseling & Planning, 34(2), 204. [Google Scholar]

- Zainudin, N., & Shaharuddin, N. S. (2022, June 1). Factors affecting individual saving behavior: A review of literature. 9th International Conference on Management and Muamalah 2022 (ICoMM 2022), Online. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, A. Y. F., & Chou, K. L. (2018). Retirement goal clarity, needs estimation, and saving amount: Evidence from Hong Kong, China. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 29(2), 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P. (1999). Recollections of a social psychologist’s career: An interview with Dr. Philip Zimbardo. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 14(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zulaihati, S., & Widyastuti, U. (2020). Determinants of consumer financial behavior: Evidence from households in Indonesia. Journal of Accounting, 6(7), 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 137 | 9631 | 62 |

| United Kingdom | 53 | 1140 | 31 |

| Netherlands | 25 | 784 | 18 |

| France | 17 | 560 | 10 |

| Germany | 25 | 508 | 24 |

| Australia | 19 | 336 | 16 |

| China | 23 | 283 | 15 |

| Italy | 22 | 271 | 20 |

| Chile | 8 | 189 | 6 |

| Canada | 17 | 164 | 8 |

| Contexts | No. of Articles | Contexts | No. of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 18 | Australia | 1 |

| India | 8 | Belarus | 1 |

| China | 6 | Botswana | 1 |

| Indonesia | 6 | Brazil | 1 |

| Malaysia | 6 | Britain | 1 |

| Vietnam | 4 | Canada | 1 |

| Japan | 3 | Ethiopia | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 3 | Gorgia | 1 |

| Thailand | 3 | Greece | 1 |

| Turkey | 3 | Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 3 | Hongkong | 1 |

| Germany | 2 | Iran | 1 |

| Ghana | 2 | Ireland | 1 |

| Korea | 2 | New Zealand | 1 |

| Netherland | 2 | European Union (9 new members) | 1 |

| Pakistan | 2 | Philippines | 1 |

| Portugal | 2 | Poland | 1 |

| Singapore | 2 | Russia | 1 |

| Spain | 2 | Rwanda | 1 |

| Sweden | 2 | South Africa | 1 |

| Uganda | 2 | Taiwan | 1 |

| Chile | 1 | UAE | 1 |

| West Africa | 1 | Ukraine | 1 |

| Methods of Data Collection | No. of Articles | Exemplar Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Survey | 74 | (Kim et al., 2025; Ramli et al., 2022; Yadav & Banerji, 2025; Uy et al., 2024; Ammer & Aldhyani, 2022) |

| Secondary Data | 21 | (Athukorala & Suanin, 2024; Gröbel & Ihle, 2018; Fang et al., 2022; Ang, 2009; Cho et al., 2014) |

| Experiment Based | 6 | (Trzcińska et al., 2022; Sayinzoga et al., 2016; Durante & Laran, 2016; Cho et al., 2014; Thaler & Benartzi, 2004) |

| Interview | 3 | (Pandey, 2018; Swasdpeera & Pandey, 2012; Garcia et al., 2011) |

| Epidemiological Approach | 1 | (Fuchs-Schündeln et al., 2020) |

| Case Study | 1 | (Jongwanich, 2010) |

| Critical Analysis | 3 | (Gomes, 2025; Hopf, 2006; Browning, 2000) |

| Randomized Field Experiment | 3 | (Behr & Jacob, 2024; Pomeranz & Kast, 2024; Calderone et al., 2018) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batham, S.; Arora, H.; Gupta, V. Investigation of the Antecedents of Personal Saving Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review Using TCM-ADO Framework. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100554

Batham S, Arora H, Gupta V. Investigation of the Antecedents of Personal Saving Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review Using TCM-ADO Framework. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(10):554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100554

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatham, Shilpi, Hitesh Arora, and Vibhuti Gupta. 2025. "Investigation of the Antecedents of Personal Saving Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review Using TCM-ADO Framework" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 10: 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100554

APA StyleBatham, S., Arora, H., & Gupta, V. (2025). Investigation of the Antecedents of Personal Saving Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review Using TCM-ADO Framework. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(10), 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100554