Do You Feel Safe Here? The Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Turnover Intention Amid COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

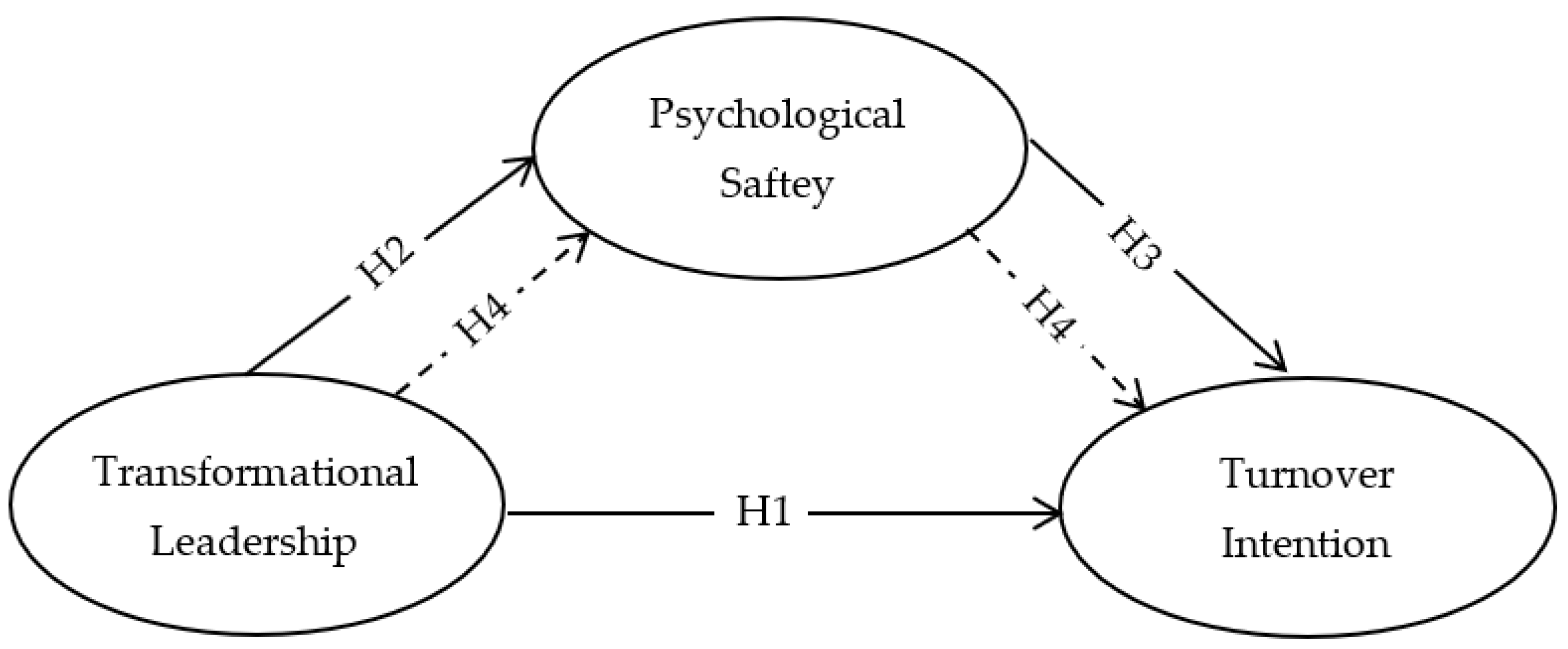

- Research question 1: What is the impact of transformational leadership on turnover intention of hotel workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Research question 2: What is the impact of psychological safety on turnover intention of hotel workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Research question 3: How does psychological safety intermediate the link between transformational leadership and turnover intention amid the COVID-19 pandemic in the hotel industry?

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Defining the Study Constructs

2.2. Transformational Leadership and Turnover Intention

2.3. Transformational Leadership and Psychological Safety

2.4. Psychological Safety and Turnover Intention

2.5. The Mediating Effect of Psychological Safety in the Link between Transformational Leadership and Turnover Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. The Study Instrument

4. Key Findings

4.1. CFA Findings

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling Results

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions and Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Abbr | Scales and Items | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Transformational Leadership | ||

| TL1 | The leader communicates a clear and positive vision of the future | Carless et al. (2000) |

| TL2 | The leader treats staff as individuals, supports and encourages their development | |

| TL3 | The leader gives encouragement and recognition to staff | |

| TL4 | The leader fosters trust, involvement and cooperation among team members | |

| TL5 | The leader encourages thinking about problems in new ways and questions assumptions | |

| TL6 | The leader is clear about his/her values and practises what he/she preaches | |

| TL7 | The leader instills pride and respect in others and inspires me by being highly competent | |

| Turnover Intention | ||

| TU8 | I often think about leaving that career | Liden et al. (1997) |

| TU9 | It would not take much to make me leave this career | |

| TU10 | I will probably be looking for another career soon | |

| Psychological Safety | ||

| PS11 | If you make a mistake on this team, it is not really held against you | Edmondson (2003) |

| PS12 | Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues | |

| PS13 | People on this team never reject others for being different | |

| PS14 | It is safe to take a risk on this team | |

| PS15 | It is easy to ask other members of this team for help | |

| PS16 | No one on this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my effort | |

| PS17 | Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized | |

Appendix B

| Measured Variable | KMO | TVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational Leadership = TL | 0.750 | 52.318 | 0.771 |

| Turnover Intention = TU | 0.736 | 54.209 | 0.780 |

| psychological Safety = PS | 0.728 | 51.662 | 0.810 |

References

- Ajzen, Icek. 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Aliedan, Meqbel M., Abu Elnasr E. Sobaih, Mansour A. Alyahya, and Ibrahim A. Elshaer. 2022. Influences of Distributive Injustice and Job Insecurity Amid COVID-19 on Unethical Pro-Organisational Behaviour: Mediating Role of Employee Turnover Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, Mansour A., Ibrahim A. Elshaer, and Abu Elnasr E. Sobaih. 2021. The Impact of Job Insecurity and Distributive Injustice Post COVID-19 on Social Loafing Behavior among Hotel Workers: Mediating Role of Turnover Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avolio, Bruce J., and Bernard M. Bass. 1995. Individual consideration viewed at multiple levels of analysis: A multilevel framework for examining the diffusion of transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 6: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, Markus, and Michael Frese. 2003. Innovation Is Not Enough: Climates for Initiative and Psychological Safety, Process Innovations, and Firm Performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior 24: 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, Bernard M., and Ronald E. Riggio. 2006. Transformational Leadership, 2nd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Peter M. 1968. Social exchange. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences 7: 452–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, Peter M., and Douglas G. Bonett. 1980. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin 88: 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, Kimberley, Arnold B. Bakker, Evangelia Demerouti, Dominique M. Sleebos, and Véronique Maduro. 2014. Uncovering the underlying relationship between transformational leaders and followers’ task performance. Journal of Personnel Psychology 13: 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breevaart, Kimberley, Arnold Bakker, Jørn Hetland, Evangelia Demerouti, Olav K. Olsen, and Roar Espevik. 2013. Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 87: 138–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan, and Duncan Cramer. 2012. Quantitative Data Analysis with IBM SPSS 17, 18 & 19: A Guide for Social Scientists. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, James M. 1978. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Carless, Sally A., Alexander J. Wearing, and Leon Mann. 2000. A short measure of transformational leadership. Journal of Business & Psychology 14: 389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, Abraham, Zachary Sheaffer, Galy Binyamin, Roni Reiter-Palmon, and Tali Shimoni. 2014. Transformational leadership and creative problem solving: The mediating role of psychological safety and reflexivity. The Journal of Creative Behavior 48: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Tso-Jen, and Chi-Min Wu. 2017. Improving the turnover intention of tourist hotel employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 28: 586–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, Russell, Erica L. Anthony, Shanna R. Daniels, and Alison V. Hall. 2017. Social Exchange Theory: A critical review with theoritical remedies. Academy of Management Annals 11: 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cropanzano, Russell, and Marie S. Mitchell. 2005. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management 31: 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deery, Margaret, and Leo Jago. 2015. Revisiting talent management, work-life balance and retention strategies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 27: 453–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeGroot, Timothy, D. Scott Kiker, and Thomas C. Cross. 2000. A Meta-Analysis to Review Organizational Outcomes Related to Charismatic Leadership. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 17: 356–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, Deanne N., Jaap J. Van Muijen, and Paul L. Koopman. 1997. Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 70: 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, James R., and Ethan R. Burris. 2007. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal 50: 869–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, Souvik, Payel Biswas, Ritwik Ghosh, Subhankar Chatterjee, Mahua Jana Dubey, Subham Chatterjee, Durjoy Lahiri, and Carl J. Lavie. 2020. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 14: 779–88. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, Amy C. 1999. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly 44: 350–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edmondson, Amy C. 2003. Managing the risk of learning: Psychological safety in work teams. In International Handbook of Organizational Teamwork. Edited by Michael A. West. London: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, Amy C., and Zhike Lei. 2014. Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1: 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edmondson, Amy C., Richard M. Bohmer, and Gary P. Pisano. 2001. Disrupted routines: Team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Administrative Science Quarterly 46: 685–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evrard, Yves, Bernard Pras, and Elyette Roux. 2000. Market: Etudes et Recherches en Marketing. Paris: Dunod. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, M. Lance, Stav Fainshmidt, Ryan L. Klinger, Amir Pezeshkan, and Veselina Vracheva. 2017. Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology 70: 113–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gom, Daria, Tek Yew Lew, Mary Monica Jiony, Geoffrey Harvey Tanakinjal, and Stephen Sondoh Jr. 2021. The Role of Transformational Leadership and Psychological Capital in the Hotel Industry: A Sustainable Approach to Reducing Turnover Intention. Sustainability 13: 10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Adam M., and Susan J. Ashford. 2008. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior 28: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, Neil, Mary Docherty, Sam Gnanapragasam, and Simon Wessely. 2020. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 368: m1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Griffeth, Rodger W., Peter W. Hom, and Stefan Gaertner. 2000. A metaanalysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management 26: 463–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, Eugen. 2019. Psychological Safety as a Potential Predictor of Turnover Intentio. Master’ thesis, Lunds University, Lund, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, Chenglin, Anqi Luo, Pengcheng Zhang, and Aimin Deng. 2020. Meta-analysis of transformational leadership in hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 32: 2137–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph R., Rolph E. Anderson, R. L. Tatham, and W. C. Black. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis. Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Haldorai, Kavitha, Woo Gon Kim, Souji Gopalakrishna Pillai, Taesu Eliot Park, and Kandappan Balasubramanian. 2019. Factors affecting hotel employees’ attrition and turnover: Application of pull-push-mooring framework. International Journal of Hospitality Management 83: 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Michael C., Girish Prayag, Peter Fieger, and David Dyason. 2020. Beyond panic buying: Consumption displacement and COVID-19. Journal of Service Management 32: 113–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, Iain. 2006. Transformational leadership: Characteristics and criticisms. Journal of Organizational Learning and Leadership 5: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hebles, Melany, Francisco Trincado-Munoz, and Karina Ortega. 2022. Stress and Turnover Intentions Within Healthcare Teams: The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Effect of COVID-19 Worry and Supervisor Support. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 758438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, Chan M. 1997. Job Satisfaction and Intent to Leave. Journal of Social Psychology 137: 677–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, Kevin L., Bruno Contreras-Moreira, Nishadi De Silva, Gareth Maslen, Wasiu Akanni, James Allen, Jorge Alvarez-Jarreta, Matthieu Barba, Dan M Bolser, Lahcen Cambell, and et al. 2020. Ensembl Genomes 2020—Enabling non-vertebrate genomic research. Nucleic Acids Research 48: D689–D695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joreskog, Karl G. 1988. Analysis of Covariance Structures. In The Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. Edited by Raymond B. Cattell. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 207–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jyoti, Jeevan, and Manisha Dev. 2014. The impact of transformational leadershipon employee creativity: The role of learning orientation. Journal of Asia Business Studies 9: 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, William A. 1990. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal 33: 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway, E. Kevin, Nick Turner, Julian Barling, and Catherine Loughlin. 2012. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: The mediating role of employee trust in leadership. Work & Stress 26: 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Saiful Islam. 2015. Using Transformational Leadership to Predict Employees’ Turnover Intention: The Mediating Effects of Trust and Employees’ Job Performance in Bangkok, Thailand”. Master’s thesis, Unversity Ban, Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Rex B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, Robert V., and Daryle W. Morgan. 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30: 607–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, Deborah, and Revecca A. Henry. 2000. Helping coworkers and helping the organization: The role of support perceptions, exchange ideology, and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30: 2028–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, Robert C., Raymond T. Sparrowe, and Sandy J. Wayne. 1997. Leader member exchange theory: The past and potential for the future. Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management 15: 47–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, Kevin B., K. Galen Kroeck, and Nagaraj Sivasubramaniam. 1996. Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic review of the MLQ literature. Leadership Quarterly 7: 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masi, Ralph J., and Robert A. Cooke. 2000. Effects of transformational leadership on subordinate motivation, empowering norms and organizational productivity. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 8: 16–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medley, Faye, and Diane R. Larochelle. 1995. Transformational Leadership and Job Satisfaction. Nursing Management 26: 64JJ–64NN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Linjuan Rita. 2014. Strategic internal communication: Transformational leadership, communication channels, and employee satisfaction. Management Communication Quarterly 28: 264–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, William H. 1982. Some Unanswered Questions in Turnover and Withdrawal Research. Academy of Management Review 7: 111–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, Ngqabutho. 2019. Testing the effect of employee engagement, transformational leadership and organisational communication on organisational commitment. Journal of Management and Marketing Review 4: 270–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, Jum C. 1978. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed. New York: Mc Graw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng, Anthony Frank, Prince Ewudzie Quansah, and Eric Boakye. 2020. The Relationship between Job Insecurity and Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Employee Morale and Psychological Strain. Management 10: 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, Dennis W. 1988. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington: Lexington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, Dennis W. 1990. The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behavior. Research in Organizational Behavior 12: 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pedhazur, Elazar J., and Liora Pedhazur Schmelkin. 1991. Measurement, Design, and Analysis: An Integrated Approach. Hillsdale: LEA, Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., and Scott B. MacKenzie. 1997. Impact of organizational citizenship behavior on organizational performance: A review and suggestions for future research. Human Performance 10: 133–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, Patrice. 2005. Méthodes de Développement d’Échelles pour Questionnaires d’Enquête. In Management des Ressources Humaines: Méthodes de Recherche en Sciences Humaines et Sociales. Edited by Patrice Roussel and Frédéric Wacheux. Paris: De Boeck Supérieur, pp. 245–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein, Alex L., Marion B. Eberly, Thomas W. Lee, and Terence R. Mitchell. 2018. Surveying the forest: A meta-analysis, moderator investigation, and future-oriented discussion of the antecedents of voluntary employee turnover. Personnel Psychology 71: 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, Edgar H., and Warren G. Bennis. 1965. Personal and Organizational Change through Group Methods: The Laboratory Approach. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaih, Abu Elnasr E. 2011. The Management of Part-Time Employees in the Restaurant Industry: A Case Study of the UK Restaurant Sector. Chisinau: Lap Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaih, Abu Elnasr E. 2018. Human resource management in hospitality firms in Egypt: Does size matter? Tourism and Hospitality Research 18: 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, Abu Elnasr E., Yasser Ibrahim, and Gaber Gabry. 2019. Unlocking the black box: Psychological contract fulfillment as a mediator between HRM practices and job performance. Tourism Management Perspectives 30: 171–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, Abu Elnasr E. Ahmed Hasanein, Meqbel Aliedan, and Hassan Abdallah. 2022. The impact of transactional and transformational leadership on employee intention to stay in deluxe hotels: Mediating role of organisational commitment. Tourism and Hospitality Research 22: 257–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, Abu Elnasr E. Ibrahim Elshaer, Ahmed Hasanein, and Ahmed Shaker Abdelaziz. 2021. Responses to COVID-19: The role of performance in the relationship between small hospitality enterprises0 resilience and sustainable tourism development. International journal of Hospitality Management 94: 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverke, Magnus, and Johnny Hellgren. 2002. The nature of job insecurity: Understanding employment uncertainty on the brink of a new millennium. Applied Psychology 51: 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Guiyao, Zhenyao Cai, Zhiqiang Liu, Hong Zhu, Xin Yang, and Ji Li. 2015. The importance of ethical leadership in employees’ value congruence and turnover. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 56: 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Steven, Caeleigh A. Landry, Michelle M. Paluszek, Thomas A. Fergus, Dean McKay, and Gordon J. G. Asmundson. 2020. Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 72: 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, Lieke L., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2012. A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. American Psychologist 67: 545–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tepper, Bennett J., and Edward C. Taylor. 2003. Relationships among supervisors’ and subordinates’ procedural justice perceptions and organizational citizenship behaviors. Academy of Management Journal 46: 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, Robert P., and John P. Meyer. 1993. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology 46: 259–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Yidong, Diwan Li, and Hai-Jiang Wang. 2021. COVID-19-induced layoff, survivors’ COVID-19-related stress and performance in hospitality industry: The moderating role of social support. International Journal of Hospitality Management 95: 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winasis, Shinta, Setyo Riyanto Djumarno, and Eny Ariyanto. 2020. The Impact of the Transformational Leadership Climate on Employee Job Satisfaction during the Covid-19 Pandemic in the Indonesian Banking Industry. Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 17: 7732–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Jen-Te, Chin-Sheng Wan, and Yi-Jui Fu. 2012. Qualitative examination of employee turnover and retention strategies in international tourist hotels in Taiwan. International journal of Hospitality Management 31: 837–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Jielin, Zhenzhong Ma, Haiyun Yu, Muxiao Jia, and Ganli Liao. 2019. Transformational leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Explore the mediating roles of psychological safety and team efficacy. Journal of Knowledge Management 24: 150–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagoršek, Hugo, Vlado Dimovski, and Miha Škerlavaj. 2009. Transactional and transformational leadership impacts on organizational learning. Journal for East European Management Studies 14: 144–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ann Yan, Anne S. Tsui, and Duan Xu Wang. 2011. Leadership behaviors and group creativity in Chinese organizations: The role of group processes. The Leadership Quarterly 22: 851–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Wen-Chi, Qing Tian, and Jia Liu. 2015. Servant leadership, social exchange relationships, and follower’s helping behaviour: Positive reci-procity belief matters. International Journal of Hospitality Management 51: 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbr | Item | Min | Max | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational Leadership | |||||||

| TL1 | The leader communicates a clear and positive vision of the future | 1 | 5 | 4.23 | 0.822 | −0.964 | 0.930 |

| TL2 | The leader treats staff as individuals, supports and encourages their development | 2 | 5 | 4.23 | 0.763 | −0.524 | −0.747 |

| TL3 | The leader gives encouragement and recognition to staff | 2 | 5 | 4.32 | 0.790 | −0.933 | 0.138 |

| TL4 | The leader fosters trust, involvement and cooperation among team members | 2 | 5 | 4.15 | 0.849 | −0.764 | −0.078 |

| TL5 | The leader encourages thinking about problems in new ways and questions assumptions | 3 | 5 | 4.37 | 0.717 | −0.683 | −0.777 |

| TL6 | The leader is clear about his/her values and practices what he/she preaches | 2 | 5 | 4.16 | 0.852 | −0.776 | −0.085 |

| TL7 | The leader instills pride and respect in others and inspires me by being highly competent | 1 | 5 | 4.24 | 0.824 | −0.977 | 0.925 |

| Turnover Intention | |||||||

| TU8 | I often think about leaving that career | 1 | 5 | 1.86 | 0.954 | 1.641 | 3.063 |

| TU9 | It would not take much to make me leave this career | 1 | 5 | 1.55 | 0.636 | 1.634 | 6.367 |

| TU10 | I will probably be looking for another career soon | 1 | 5 | 1.52 | 0.600 | 1.551 | 6.899 |

| Team Psychological Safety | |||||||

| PS11 | If you make a mistake on this team, it is not really held against you | 3 | 5 | 4.38 | 0.718 | −0.706 | −0.760 |

| PS12 | Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues | 2 | 5 | 4.22 | 0.780 | −0.514 | −0.860 |

| PS13 | People on this team never reject others for being different | 1 | 5 | 4.24 | 0.824 | −0.977 | 0.925 |

| PS14 | It is safe to take a risk on this team | 2 | 5 | 4.23 | 0.763 | −0.524 | −0.747 |

| PS15 | It is easy to ask other members of this team for help | 2 | 5 | 4.32 | 0.790 | −0.933 | 0.138 |

| PS16 | No one on this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my effort | 2 | 5 | 4.15 | 0.849 | −0.764 | −0.078 |

| PS17 | Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized | 3 | 5 | 4.30 | 0.754 | −0.560 | −1.035 |

| Factors and Items | SFL | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Transformational Leadership (Carless et al. 2000) (α = 0.771) | 0.978 | 0.867 | 0.520 | 0.338 | 0.931 | |||

| The leader communicates a clear and positive vision of the future | 0.960 | |||||||

| The leader treats staff as individuals, supports and encourages their development | 0.932 | |||||||

| The leader gives encouragement and recognition to staff | 0.928 | |||||||

| The leader fosters trust, involvement and cooperation among team members | 0.940 | |||||||

| The leader encourages thinking about problems in new ways and questions assumptions | 0.917 | |||||||

| The leader is clear about his/her values and practises what he/she preaches | 0.972 | |||||||

| The leader instills pride and respect in others and inspires me by being highly competent | 0.864 | |||||||

| 2-Turnover Intention (Liden et al. 1997) (α = 0.780) | 0.964 | 0.899 | 0.667 | 0.432 | 0.189 ** | 0.948 | ||

| I often think about leaving that career | 0.866 | |||||||

| It would not take much to make me leave this career | 0.995 | |||||||

| I will probably be looking for another career soon | 0.978 | |||||||

| 3-Psychological Safety (Edmondson 2003) (α = 0.810) | 0.982 | 0.885 | 0.667 | 0.392 | 0.591 ** | 0.776 ** | 0.940 | |

| If you make a mistake on this team, it is not really held against you | 0.938 | |||||||

| Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues | 0.945 | |||||||

| People on this team never reject others for being different | 0.966 | |||||||

| It is safe to take a risk on this team | 0.918 | |||||||

| It is easy to ask other members of this team for help | 0.901 | |||||||

| No one on this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my effort | 0.981 | |||||||

| Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized | 0.933 |

| Result of the Structural Model | β | C-R t-Value | R2 | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

H1—Transformational leadership  turnover intention turnover intention | −0.39 *** | 6.298 | Supported | |

H2—Transformational leadership  psychological safety psychological safety | 0.72 *** | 11.315 | Supported | |

H3—Psychological safety  turnover intention turnover intention | −0.42 *** | 3.674 | Supported | |

| Turnover Intention | 0.759 |

| Parameter | Estimate | Lower | Upper | p | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

H4—Transformational leadership  turnover intention turnover intention  psychological safety psychological safety | 0.318 | 0.145 | 0.411 | 0.059 | 0.059 > 0.05 Perfect Mediation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sobaih, A.E.E.; Gharbi, H.; Abu Elnasr, A.E. Do You Feel Safe Here? The Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Turnover Intention Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080340

Sobaih AEE, Gharbi H, Abu Elnasr AE. Do You Feel Safe Here? The Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Turnover Intention Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(8):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080340

Chicago/Turabian StyleSobaih, Abu Elnasr E., Hassane Gharbi, and Ahmed E. Abu Elnasr. 2022. "Do You Feel Safe Here? The Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Turnover Intention Amid COVID-19 Pandemic" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 8: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080340

APA StyleSobaih, A. E. E., Gharbi, H., & Abu Elnasr, A. E. (2022). Do You Feel Safe Here? The Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Turnover Intention Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(8), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080340